He would fiddle his way out of the cotton fields of Texas and onto the film sets of Hollywood and the stages of Nashville, appearing in twenty-six movies and recording more than four hundred songs. His “San Antonio Rose” would achieve anthemic status in his home state and sell in the millions. He would be honored by the Country Music Hall of Fame, the state of Texas, and the Texas Trail of Fame at the stockyards in Fort Worth—the city where he would begin and end his long musical career.

James Robert Wills was born in 1905 in Moss Springs, a now-vanished settlement just east of Kosse in Limestone County. Jim Rob, as he was known then, was the first of ten children born to tenant farmers John Tompkins Wills and Emmaline Foley Wills. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

James Robert Wills was born in 1905 in Moss Springs, a now-vanished settlement just east of Kosse in Limestone County. Jim Rob, as he was known then, was the first of ten children born to tenant farmers John Tompkins Wills and Emmaline Foley Wills. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

When Jim Rob was born, a relative who was thought to be clairvoyant looked at his hands and said he had the fingers of a fiddler.

But it didn’t take a clairvoyant to see rosin and a bow in that baby’s future: Wills would later count the fiddlers on both sides of his family: father, both grandfathers, nine uncles, and five aunts.

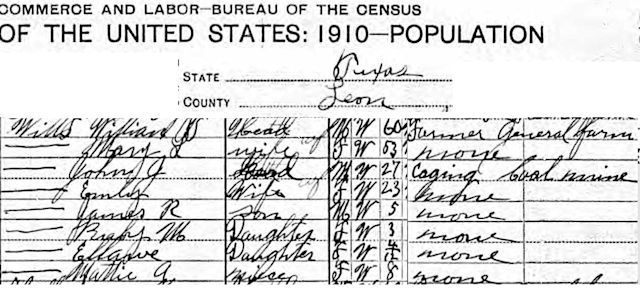

By 1910 three generations of Willses had moved to adjacent Leon County. Jim Rob and his siblings and parents lived next to Jim Rob’s grandparents. Father John apparently had temporarily given up farming: He listed his occupation as a cager in a coal mine.

By 1910 three generations of Willses had moved to adjacent Leon County. Jim Rob and his siblings and parents lived next to Jim Rob’s grandparents. Father John apparently had temporarily given up farming: He listed his occupation as a cager in a coal mine.

But in 1913 the family moved again, this time five hundred miles northwest to Hall County to resume farming. They traveled in two covered wagons. Jim Rob rode on his donkey, Little Joe.

The trip took two months because the Willses stopped at farms along the way to pick cotton. They slept in cabins provided for the pickers or slept under their wagons.

In Hall County the Willses farmed rented land, at times living in dugouts because lumber for houses was scarce, and thus wooden houses were expensive.

The Wills family also earned money by playing for dances. Father John especially was a sought-after fiddler. The first instruments son Jim Rob played were guitar and mandolin. Only later did he cotton to the fiddle.

Jim Rob played fiddle at his first dance in 1915 to fill in for his father.

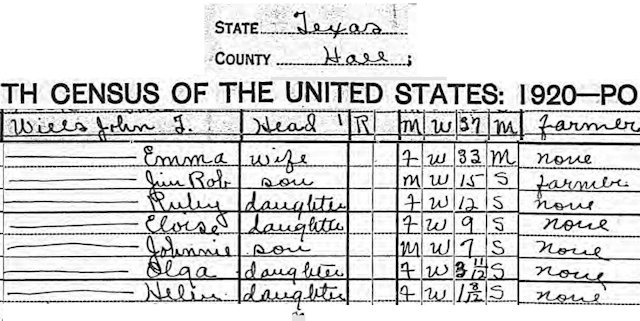

By 1920 Jim Rob had five siblings.

By 1920 Jim Rob had five siblings.

Farming on a small scale in dry west Texas put food on the table but little money in the bank. But about 1922 father John had saved enough money to stop renting farms and buy his own. He bought six hundred acres outside of Turkey and built a house. The family would live there longer than any other location: ten years.

The Willses picked cotton all day and played music at dances at night, traveling as much as forty miles, at first by horse and buggy or horseback, later by Model T Ford. They traveled even as far as the 6666 Ranch in King County and the Matador Ranch in Motley County.

As the oldest sibling in a big family, Jim Rob Wills worked hard. In addition to picking cotton and playing at dances, during the 1920s Wills worked as a smelter, shoeshine boy, carpenter, salesman, barber, even preacher.

In 1926 Wills married Edna Posey. They moved into one of the cotton shacks on the Wills farm.

Bob gradually devoted more time to barbering in Turkey and playing fiddle. Biographer Charles Townsend in San Antonio Rose: The Life and Music of Bob Wills writes that Wills became so popular as a fiddler that people requested that he play for them on their death bed.

In 1929 Jim Rob, Edna, and daughter Robbie Jo moved to the big city: Fort Worth. Wills could not find a job barbering, but he was hired to perform in Doc’s Medicine Show. Jim Rob played fiddle, danced jigs, and performed blackface comedy. The show already had a performer named “Jim,” so Doc began calling Wills “Bob.”

Between acts Bob Wills helped Doc work the crowd, pitching a “good for what ails you” patent medicine that was mostly alcohol.

At one show Wills was noticed by Herman Arnspiger, a struggling guitar player. The two began to perform together as the Wills Fiddle Band and soon appeared on local radio stations. The pair caught the ear of a representative of the Brunswick Record Corporation. On November 1, 1929—eight days after the Great Depression began to make earning money even more difficult—Wills and Arnspiger went to Dallas to record a record. One side was a Wills family breakdown, and the other was a blues song in the repertory of African-American singer Bessie Smith.

(Wills’s daughter Rosetta recalled that her father was such a fan of Bessie Smith that “he once rode fifty miles on horseback just to see her perform live.”)

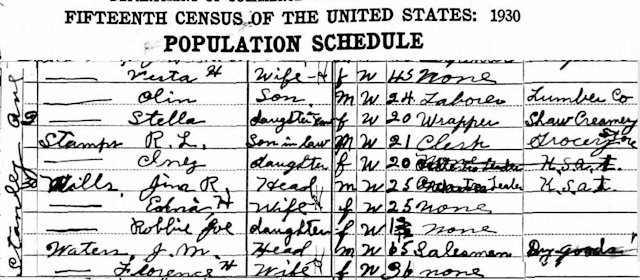

In 1930 Wills and his wife lived on Stanley Avenue on the South Side. He listed himself as “band leader” at radio station KSAT.

In 1930 Wills and his wife lived on Stanley Avenue on the South Side. He listed himself as “band leader” at radio station KSAT.

After the day-in-day-out sameness of farm life in west Texas, in Fort Worth big city life came at Bob Wills in jig time. One night Wills was playing “St. Louis Blues” at a house dance on the South Side when a stranger took the stage and began to sing along.

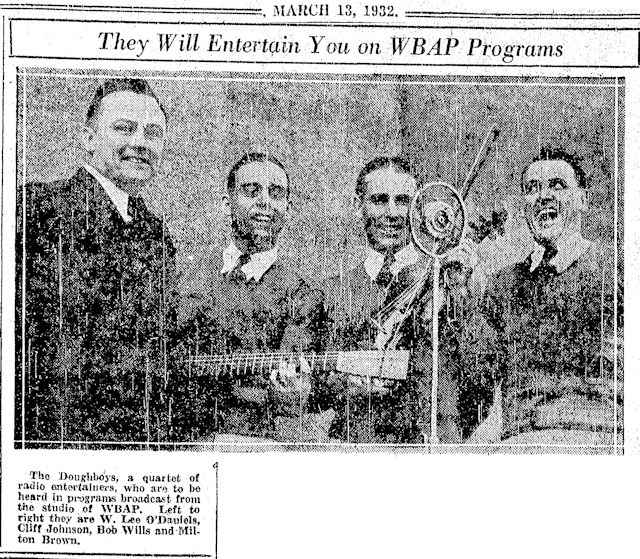

That stranger was Milton Brown.

And thus did meet the two men most often credited with creating western swing music. Some music historians (such as Wills biographer Townsend) credit Wills. Others (such as Brown biographer Cary Ginell) credit Brown. Today Wills is better remembered in part because his career would last forty years: ten times that of Brown.

Both men were innovators.

Bob Wills would become a musical maverick, bending and blending genres without regard to rules or race: African-American blues, jazz, country, big-band swing, hillbilly fiddle music descended from traditional Scots and Irish music. He had no formal musical training. His musical education came from mainly two sources: his family of fiddlers and his neighbors.

And many of his neighbors were African Americans.

The Willses lived next to African-American farmers, worked alongside African Americans in the fields, and employed African Americans on the Wills farms. Aside from his siblings, young Bob had more African American than white playmates. Wills heard the field hollers and work songs of African Americans. Early on he developed an appreciation for the music he heard played by African Americans, especially the blues.

“I don’t know whether they made them up as they moved down the cotton rows or not,” Wills recalled, “but they sang blues you never heard before.”

Wills also loved African-American music featuring horns.

“They generally always had trumpets and guitars,” he recalled, “and I will never forget how well they played them. . . . I’ve loved horns since I was a little boy.”

Bandleader Wills would become famous for his hollers of enthusiasm (“Ahhh-haaaa,” “brother Stricklin,” “Lawd, Lawd”). Ginell in Milton Brown and the Founding of Western Swing writes that Wills’s hollers were “derived mainly from his experiences in medicine and minstrel shows.”

But Townsend in San Antonio Rose writes that such hollers “came directly” from Wills’s working with African Americans in the fields.

Soon after Wills and Milton Brown met, Brown and his brother Derwood joined the Wills Fiddle Band. The band played at house dances, dance halls, the Eagles lodge hall downtown, medicine and minstrel shows. Wills, with Brown as his straight man, sometimes performed comedy in blackface and tap danced buck-and-wing style.

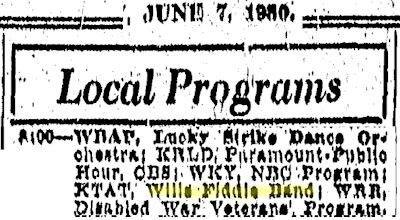

The band performed for a brief time on radio station KTAT.

The band performed for a brief time on radio station KTAT.

Then came another break. In 1930 Wills, Arnspiger, and the two Browns were hired to perform on radio station WBAP as the “Aladdin Laddies,” sponsored by the Aladdin Mantel Lamp Company.

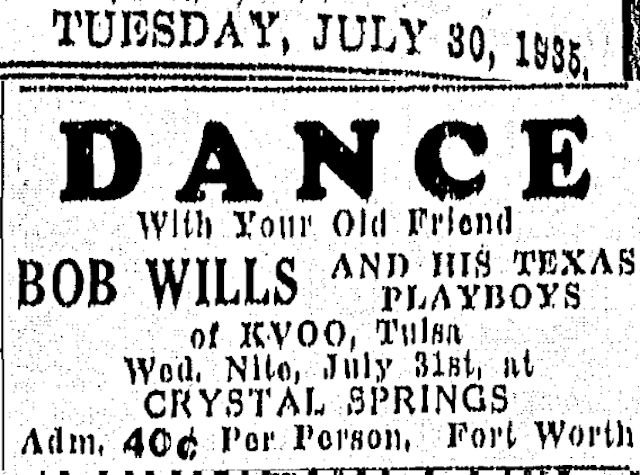

The band also began playing at Sam Cunningham’s Crystal Springs dance hall northwest of town.

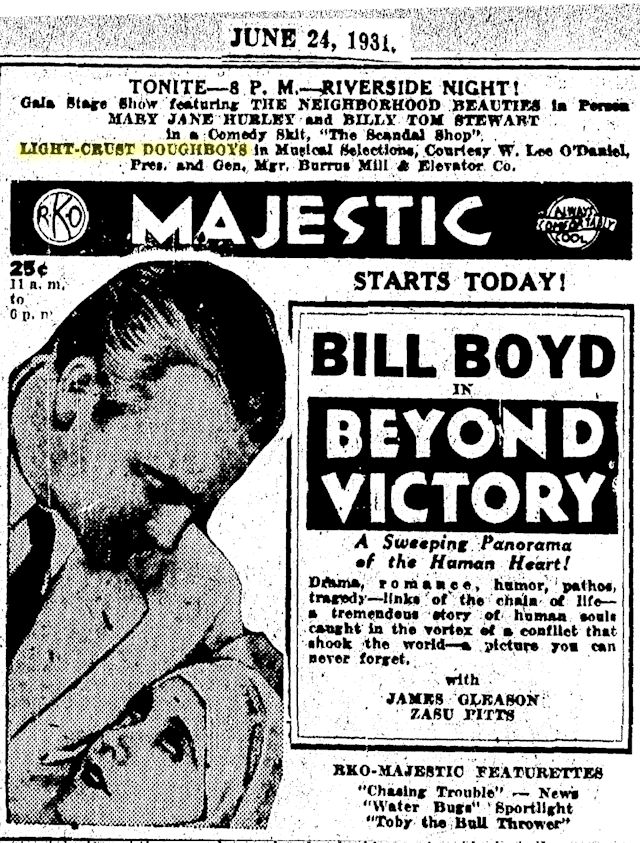

Early in 1931 came another break. Wilbert Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, president of Burrus Mills, maker of Light Crust flour, agreed to sponsor a radio program by the band on station KFJZ, which broadcast from a tiny studio in Henry Clay Meacham’s department store.

Early in 1931 came another break. Wilbert Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, president of Burrus Mills, maker of Light Crust flour, agreed to sponsor a radio program by the band on station KFJZ, which broadcast from a tiny studio in Henry Clay Meacham’s department store.

But O’Daniel gave the band only thirty days to prove its worth to him.

During the first broadcast Wills jokingly referred to his band as the “Light Crust Doughboys,” and the name stuck.

The program proved to be popular, but the band didn’t take any chances:

Years later O’Daniel recalled a Doughboy ruse: “As the first thirty-day trial period neared an end, I doubted whether it would be worthwhile continuing—much as I enjoyed hearing the boys on the air myself. There had been practically no phone calls and hardly any letters or cards from listeners. Then all of a sudden I found about thirty cards on my desk. Thirty people had written in to say how much they enjoyed the Light Crust Doughboys. Yes sir, was I impressed! Then I got to looking closely at the postcards. There were just three handwritings on almost thirty applause cards! That may have been the birth of the stacked postcard poll. The trick didn’t fool me, but I figured there wasn’t anything phony about the music those boys played. So I renewed their contract.”

O’Daniel paid each Doughboy $7.50 a week ($125 today). For that sum the band performed on the radio once a day and worked forty hours a week at “real” job at the mill. Wills drove a truck. Arnspiger loaded flour onto freight cars. Milton Brown worked in the sales and promotion department.

O’Daniel paid each Doughboy $7.50 a week ($125 today). For that sum the band performed on the radio once a day and worked forty hours a week at “real” job at the mill. Wills drove a truck. Arnspiger loaded flour onto freight cars. Milton Brown worked in the sales and promotion department.

The pay was low, but the radio exposure was good publicity for the band’s performances beyond the studio of KFJZ.

But then O’Daniel ordered Wills, Brown et al. to stop performing at dances and Crystal Springs.

So, Brown quit the Doughboys and formed Milton Brown and His Musical Brownies. Brown could make more money playing at Crystal Springs in a night than O’Daniel paid him in a week.

Wills was disgruntled but stayed in the Doughboys for the job security.

For a while.

Wills auditioned vocalists and replaced Milton Brown with Thomas Elmer Duncan from Whitney.

Then Wills and O’Daniel got crossways. Wills had missed some broadcasts because he was hungover. Also father John Wills had lost his farm to the bad economy. O’Daniel had let John live and work on O’Daniel’s farm near Fort Worth.

Fine.

But John Wills felt that O’Daniel treated him like a peasant. Finally one day in 1933 John threatened to beat O’Daniel with a three-foot bois d’arc singletree.

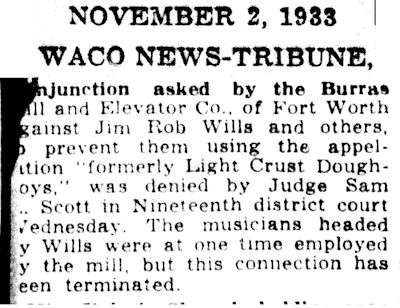

With that, Bob Wills quit the Doughboys. That gutted the band, and O’Daniel would hound Wills with lawsuits and pressure radio stations not to hire him.

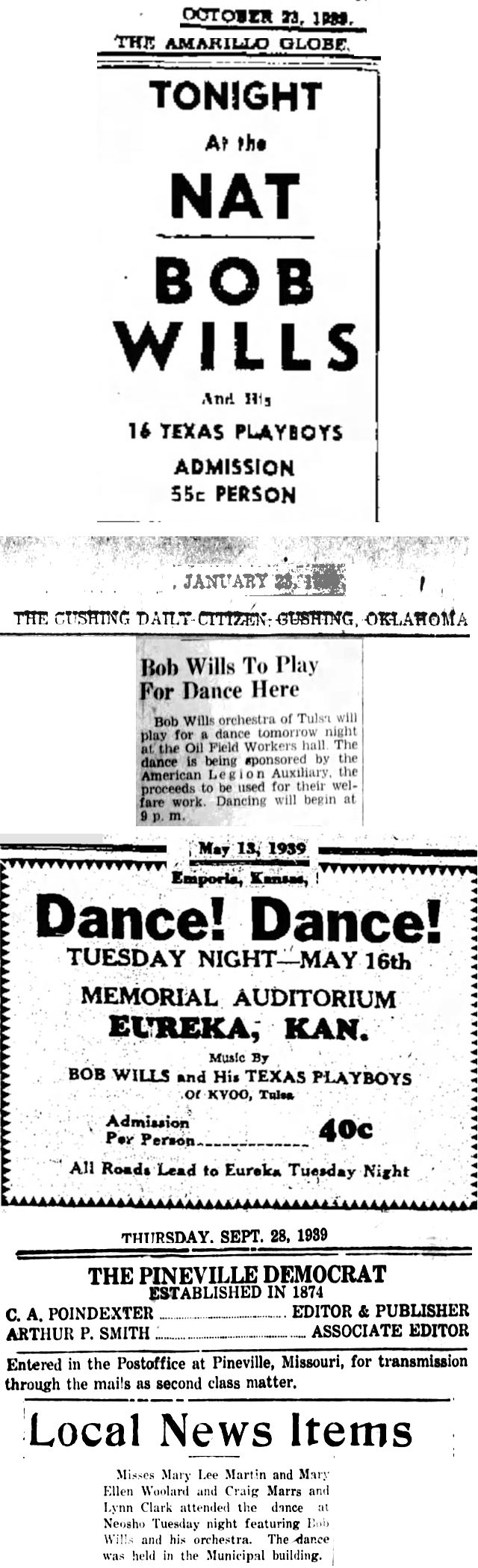

The life of a musician can be as rootless as that of a cotton picker. After five years in Fort Worth, in 1933 Wills moved with his band to Waco for a few months. There the band became “Bob Wills and His Playboys.” In 1934 the band moved to Oklahoma City, where it became “Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.”

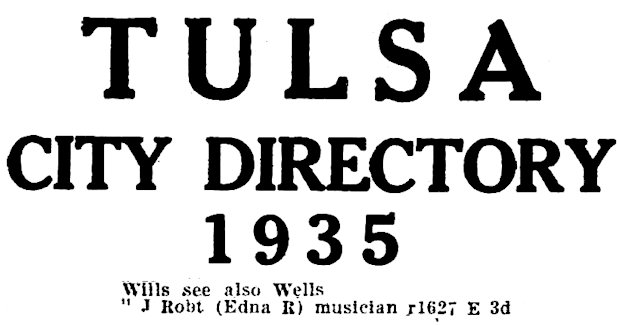

But O’Daniel pressured an Oklahoma City radio station to fire the band, and after only a few days Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys moved to Tulsa.

O’Daniel sued Wills when Wills advertised members of his new band as “formerly Light Crust Doughboys,” seeking an injunction and $10,000 damages. O’Daniel lost and appealed two times. Judges ruled that because the claim that band members were “formerly Light Crust Doughboys” was factual, no damage had been done to O’Daniel.

O’Daniel sued Wills when Wills advertised members of his new band as “formerly Light Crust Doughboys,” seeking an injunction and $10,000 damages. O’Daniel lost and appealed two times. Judges ruled that because the claim that band members were “formerly Light Crust Doughboys” was factual, no damage had been done to O’Daniel.

Even after Wills moved to Tulsa, he continued to perform at Crystal Springs. He also continued to tweak his band. He hired his old friend Herman Arnspiger, who had joined the Doughboys musical mutiny and fled O’Daniel. Wills hired pianist Al Stricklin. He hired two more Doughboys guitarists: Sleepy Johnson and eighteen-year-old Leon McAuliffe. As a Playboy McAuliffe would be a pioneer steel guitarist.

Even after Wills moved to Tulsa, he continued to perform at Crystal Springs. He also continued to tweak his band. He hired his old friend Herman Arnspiger, who had joined the Doughboys musical mutiny and fled O’Daniel. Wills hired pianist Al Stricklin. He hired two more Doughboys guitarists: Sleepy Johnson and eighteen-year-old Leon McAuliffe. As a Playboy McAuliffe would be a pioneer steel guitarist.

And Wills began to add instruments not commonly heard in string bands: horns and drums.

Wills was achieving professional success but at some personal cost.

Wills divorced his wife Edna in 1935, citing her jealous nature. For her part, she suspected him of having affairs during most of their marriage.

In 1934 Bob had decided he needed to learn some music theory. He began taking lessons from Ruth McMaster, a Tulsa concert violinist. As a classically trained musician Ruth sometimes cringed at her famous student’s musicianship, but she appreciated what he was contributing to American music.

They were married in August 1936.

And divorced in December.

In January 1938 Bob married Mary Helen Hames Brown, the daughter of Bill Hames, who would establish the Forest Park miniature train ride.

Mary Helen also was the widow of Milton Brown, who had been killed in a car wreck in 1936.

Bob and Mary Helen were married for five months. They divorced but remarried two months later for one month and divorced again. She was his third and fourth wife.

The cause of the two divorces? Bob Wills suffered from an ailment that has been the subject of many a country song: a suspicious mind.

In July 1939 Bob married Mary Louise Parker. She was sixteen. Wills was thirty-four.

When they divorced in June 1941 Mary Louise cited his jealousy.

Meanwhile, during the years 1935-1937 the band recorded for the Brunswick label: “Trouble in Mind,” “Maiden’s Prayer,” “Spanish Two Step,” “Steel Guitar Rag.”

In 1937 at a recording session in Dallas in July, the studio was so hot that members of the band and the recording crew worked in their underwear.

One song to come out of the BVDs Session was “Ding Dong Daddy.”

In November 1938 the band had another recording session in Dallas, this time for the Columbia Records label. Wills had rearranged the instrumental “Spanish Two Step” into a new song. Art Satherley of Columbia loved the song and asked Wills what the title was. Wills said he had not entitled the song.

Satherley suggested “San Antonio Rose.”

In addition to recording in Tulsa, the band performed on Tulsa radio station KVOO, sponsored by Red Star Milling Company.

Red Star even marketed Play Boy brand flour and bread.

Red Star even marketed Play Boy brand flour and bread.

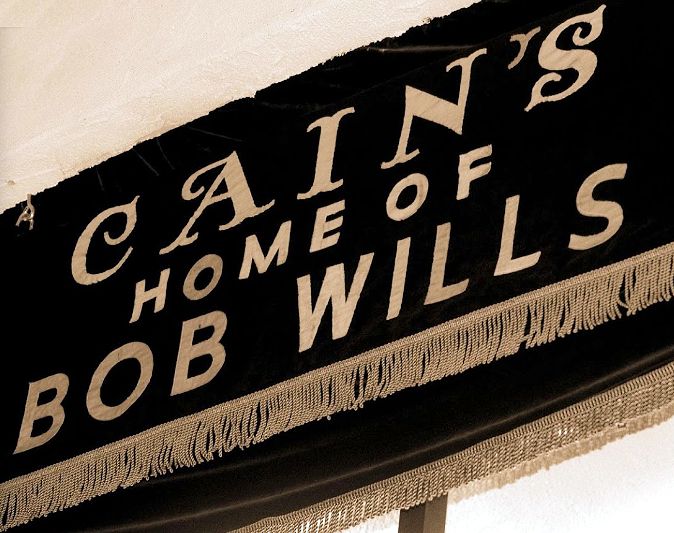

The band also performed at and broadcast from Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa.

The band also performed at and broadcast from Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa.

And the band continued to travel to perform at dances and rodeos.

And the band continued to travel to perform at dances and rodeos.

And funerals. “No Disappointments in Heaven” was one song Wills was often asked to sing at last rites.

By the late thirties Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys had become the most popular dance band in the Southwest.

In the 1940s they would go nationwide.

“Deep Within My Heart . . .” (Part 2): From Tulsa to Cowtown and “Back to Tulsa”