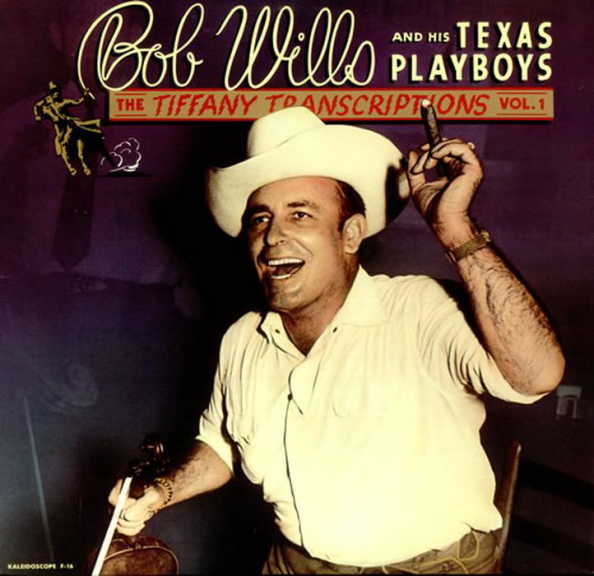

By 1940 Bob Wills (see Part 1) and the core of his Texas Playboys band (Tommy Duncan, Herman Arnspiger, Leon McAuliffe, Al Stricklin) had performed together long enough to be rock-solid musically. Wills had built the cosmopolitan band he wanted. The Playboys were a human jukebox, able to play anything from hillbilly to jazz to Dixieland to blues to swing.

In April 1940 the band went to Dallas to record for Columbia Records.

Wills, with the help of band members, wrote lyrics for their 1938 instrumental “San Antonio Rose.”

The new version with lyrics—“New San Antonio Rose”—was an instant hit. Gold. Literally. Wills won a gold record for the recording in 1940. When Bing Crosby recorded it a year later, he won a gold record.

The song was the band’s first national hit. Now all of America, not just Texas and Oklahoma, was listening to Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.

The song would become immortal, sell millions of copies, be performed and recorded by hundreds of performers in dozens of countries, be sung from space by Apollo 12 astronauts Charles Conrad and Alan Bean.

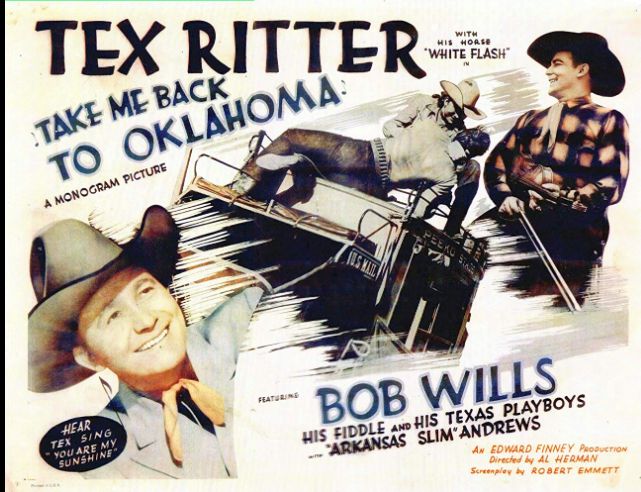

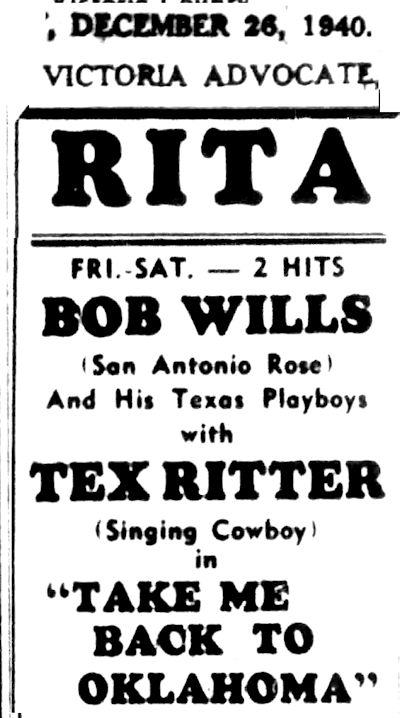

But even before the phenomenon of “San Antonio Rose,” Bob Wills had caught the attention of Hollywood. In the summer of 1940 Wills and a few of his band members appeared in Monogram Pictures’ Take Me Back to Oklahoma starring Tex Ritter. The movie introduced another Wills song that would become a classic: “Take Me Back to Tulsa,” written by Wills and Tommy Duncan.

But even before the phenomenon of “San Antonio Rose,” Bob Wills had caught the attention of Hollywood. In the summer of 1940 Wills and a few of his band members appeared in Monogram Pictures’ Take Me Back to Oklahoma starring Tex Ritter. The movie introduced another Wills song that would become a classic: “Take Me Back to Tulsa,” written by Wills and Tommy Duncan.

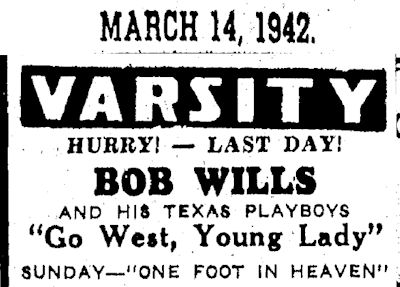

In 1941 Wills and a few band members appeared in Go West, Young Lady starring Glenn Ford.

In 1941 Wills and a few band members appeared in Go West, Young Lady starring Glenn Ford.

Then came December 7. Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys reacted like so many other Americans. Charles Townsend in San Antonio Rose: The Life and Music of Bob Wills writes that Tommy Duncan was the first band member to enlist in the Army. Some enlisted. Others worked in defense plants.

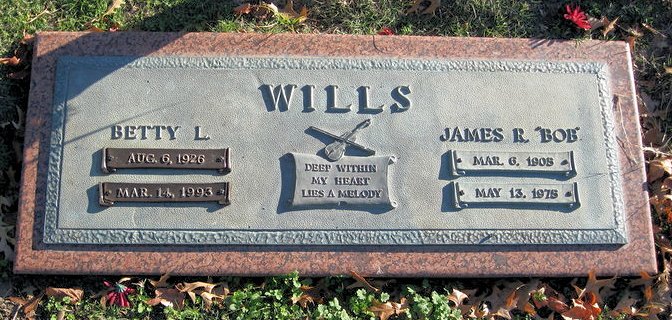

In August 1942, after four marriages in just three years, Bob Wills married for the sixth time. He had met Betty Anderson at a dance at Cain’s Academy in Tulsa. For James Robert Wills, the sixth time would be the charm.

That year Wills filmed eight westerns starring Russell Hayden for Columbia Pictures. Columbia rushed the production schedule to allow cast members to enlist ASAP.

Which Bob Wills did in December 1942. He was assigned to Camp Howze in Gainesville. However, he was thirty-eight years old, and the physical demands of Army life showed that he was not fit. He was discharged in 1943.

Bob and Betty moved to Los Angeles, where Wills began regrouping his band as members returned to civilian life. The band performed on radio station KMTR, and Bob resumed his movie career.

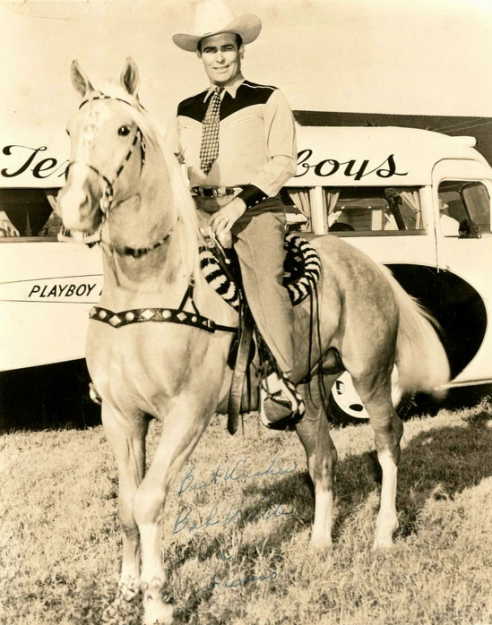

The man who had been called a “hillbilly fiddler” a few years earlier was now called an “orchestra leader,” a “movie star.” The man who had holes in the soles of his shoes when he came to Fort Worth now wore custom cowboy boots and diamond stickpins, drove a Cadillac, owned ranches and fine horses.

The man who had been called a “hillbilly fiddler” a few years earlier was now called an “orchestra leader,” a “movie star.” The man who had holes in the soles of his shoes when he came to Fort Worth now wore custom cowboy boots and diamond stickpins, drove a Cadillac, owned ranches and fine horses.

By 1944 the Playboys band had grown to twenty-two instrumentalists and two vocalists. The band was as much a horn band as a string band.

The band traveled on the Playboy Limited bus.

The band traveled on the Playboy Limited bus.

Wills made movies, performed on the radio, and toured the country with a thirteen-piece version of the Playboys in a road show called “Bob Wills and His Great Vaudeville Show.” One year he was home only seventeen days.

Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys were drawing audiences comparable with those drawn by Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Xavier Cugat, Harry James.

Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys were drawing audiences comparable with those drawn by Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Xavier Cugat, Harry James.

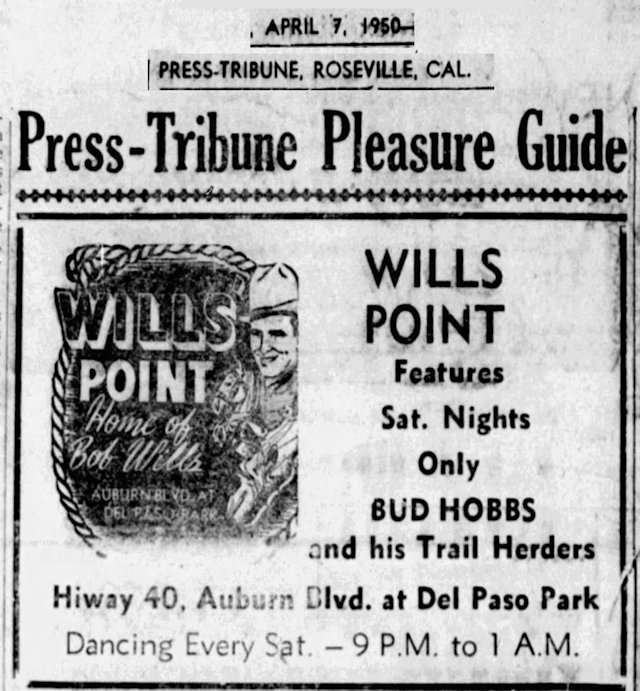

In 1947 Wills bought a new home and new base of operations: the Aragon Ballroom near Sacramento, renamed “Wills Point.” Wills and Betty and son and daughter James Jr. and Carolyn lived there, as did several band members and their families. Wills Point became the new home of the Texas Playboys, but other bands performed there.

In 1947 Wills bought a new home and new base of operations: the Aragon Ballroom near Sacramento, renamed “Wills Point.” Wills and Betty and son and daughter James Jr. and Carolyn lived there, as did several band members and their families. Wills Point became the new home of the Texas Playboys, but other bands performed there.

By late 1948 Wills and vocalist Tommy Duncan were the only original Playboys left. Then, in September, Duncan left to form his own band. The loss probably would have been fatal to a band less established and a bandleader less determined.

When the band had a recording session in Hollywood in April 1950 Wills was still searching for his next Tommy Duncan. Wills used seven vocalists in the session. He struck gold again with one: Myrl “Rusty” McDonald sang lead vocal on a song for which Bob and his father had written the melody and Bob’s brother Billy Jack had written the lyrics: “Faded Love.”

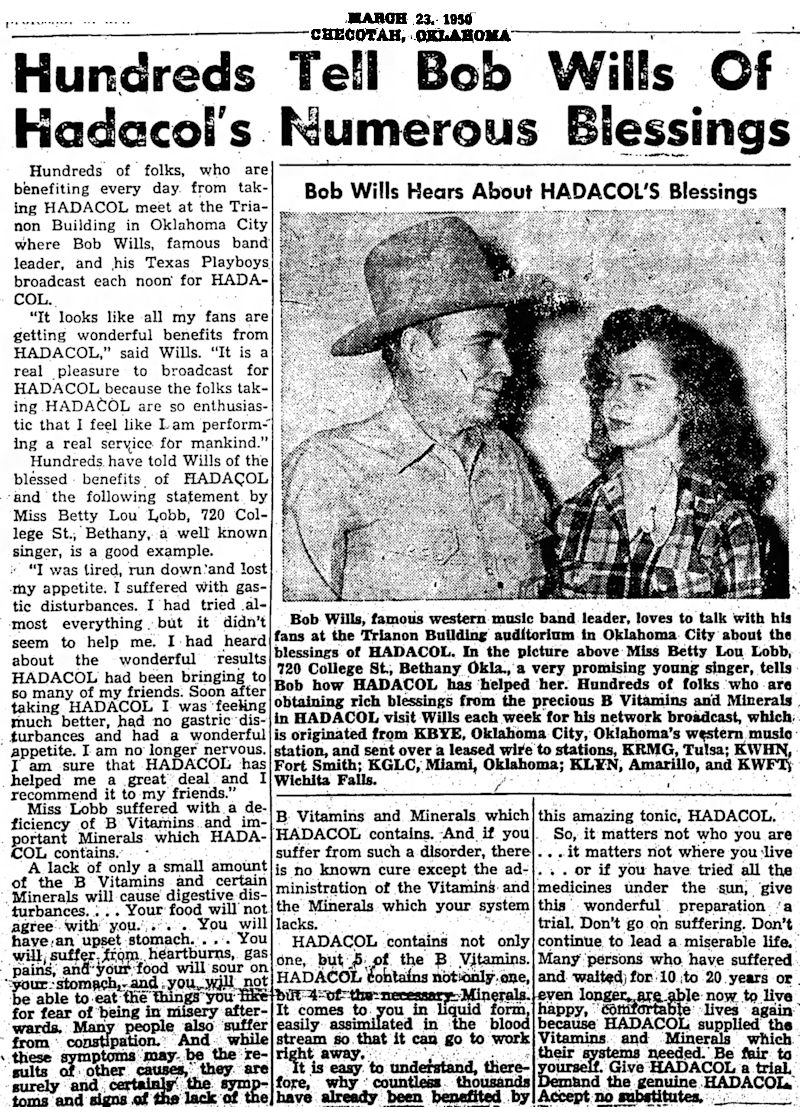

In 1949 Wills soured on California and moved to Oklahoma City. There his radio program sponsor was the patent medicine Hadacol. Hadacol, containing 12 percent alcohol, was popular in dry counties of the South.

In 1949 Wills soured on California and moved to Oklahoma City. There his radio program sponsor was the patent medicine Hadacol. Hadacol, containing 12 percent alcohol, was popular in dry counties of the South.

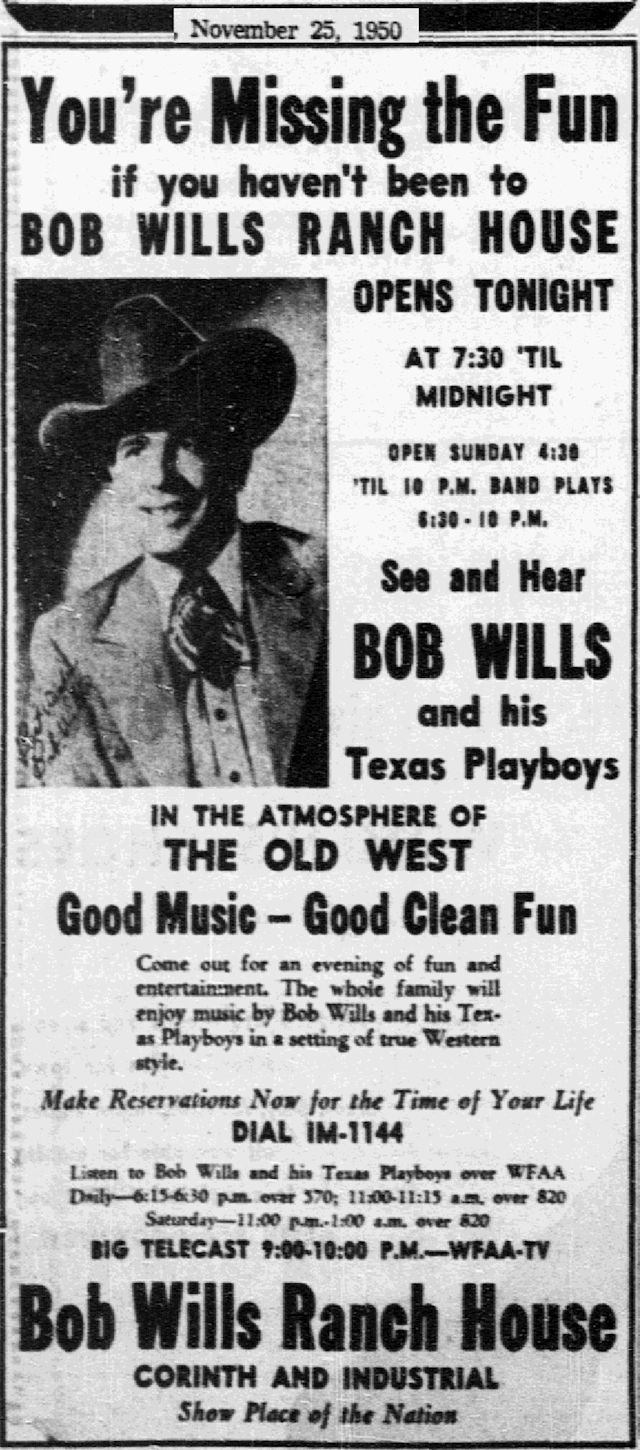

A year later Wills moved to Dallas, where he opened Bob Wills Ranch House (today the Longhorn Ballroom), built by his friend O. L. (“Thanks to all of you for helping O. L. Nelms make another million”) Nelms. The venue was huge, almost as big as a football field. But Wills made some poor business decisions and soon was in financial trouble. He had to tour constantly to earn money to pay his debts.

A year later Wills moved to Dallas, where he opened Bob Wills Ranch House (today the Longhorn Ballroom), built by his friend O. L. (“Thanks to all of you for helping O. L. Nelms make another million”) Nelms. The venue was huge, almost as big as a football field. But Wills made some poor business decisions and soon was in financial trouble. He had to tour constantly to earn money to pay his debts.

Note that Wills also performed twice a week on WFAA radio. WFAA-TV also broadcast from the Ranch House on Saturday nights.

Finally Wills got tired of the financial aggravation and in early 1952 bailed out of his lease. Nelms then leased the Ranch House to Jack Ruby. This photo shows Ruby at the Ranch House with, from left, Bobby Peters, Little Jimmy Dickens, and musician Leo Teel.

Finally Wills got tired of the financial aggravation and in early 1952 bailed out of his lease. Nelms then leased the Ranch House to Jack Ruby. This photo shows Ruby at the Ranch House with, from left, Bobby Peters, Little Jimmy Dickens, and musician Leo Teel.

Early in 1953 the Willses ping-ponged back to Wills Point in California.

But only briefly.

Late in 1953 they ping-ponged back to Texas, this time Amarillo, where the band performed on radio station KGNC.

But Wills could not seem to be still. He returned to Wills Point in 1954.

Ping.

Wills hosted his own TV show in Los Angeles, signed a recording contract with Decca.

In 1955 Betty gave birth to the couple’s fifth child, Cindy.

In 1956 the Willses moved back to Amarillo.

Pong.

That year Wills recorded in Nashville, using some of that city’s talent, including fiddle master Tommy Jackson, who the next year would play fiddle on Bobby Helms’s recording of Lawton Williams’s “Fraulein.”

In 1957—you guessed it—Wills moved yet again, this time to Abilene.

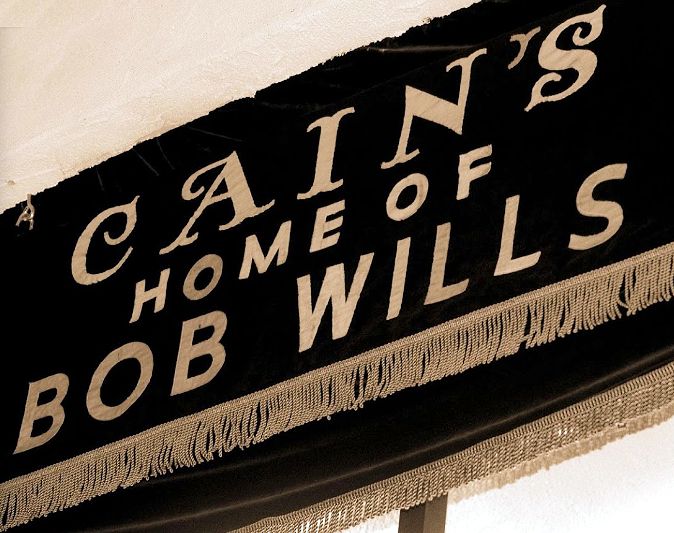

But by the end of the year he took himself “back to Tulsa,” this time to help his brother Johnny Lee, whose band performed at Cain’s Ballroom. Wills once again performed on radio station KVOO, which had first broadcast him in 1934.

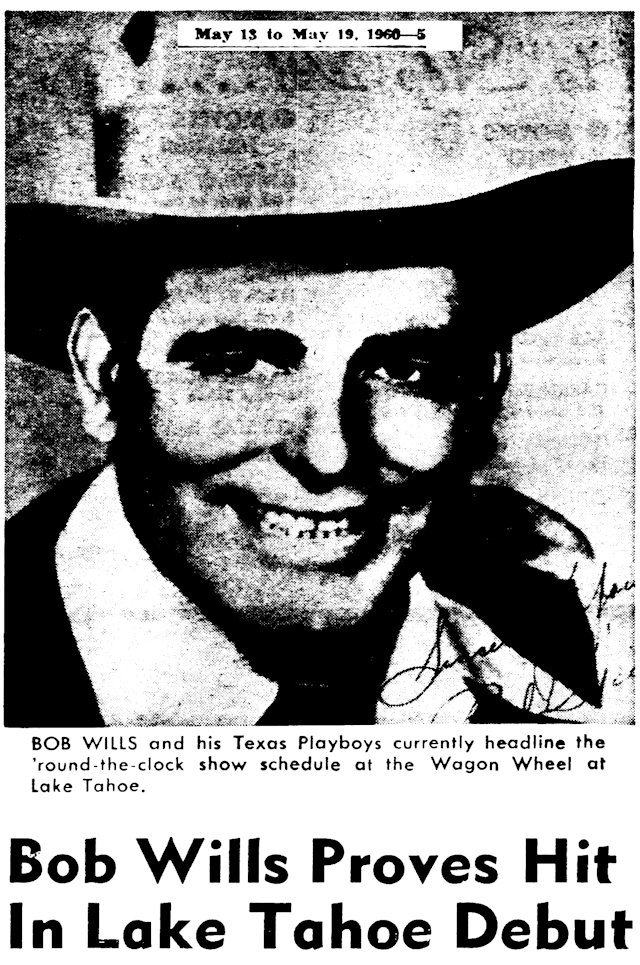

Meanwhile Wills found new audiences: in the casinos of Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe. But, biographer Townsend writes, when Wills was performing, if members of his audience left the room to go gamble (which the casino operators encouraged), Wills’s feelings were hurt.

Meanwhile Wills found new audiences: in the casinos of Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe. But, biographer Townsend writes, when Wills was performing, if members of his audience left the room to go gamble (which the casino operators encouraged), Wills’s feelings were hurt.

In 1959 Wills, nostalgic for the glory days of Tulsa, telephoned Tommy Duncan in California and invited him to Las Vegas. The two had a joyous reunion and decided to tour and record together. Their first album together was “Together Again.”

But in 1962 Bob Wills was fifty-seven years old. He had traveled many a mile, fiddled many a tune (and emptied many a bottle) since Turkey, Texas. In November, as he was driving to San Antonio, Wills’s body told him, to quote his 1945 recording, “I can’t go on this way”: Wills suffered a heart attack.

A year later Carl Johnson, a fan in Fort Worth, offered Wills $10,000 to move from Tulsa to Fort Worth. No strings attached.

Wills accepted.

In 1964 Wills sold his beloved Texas Playboys to Carl Johnson and agreed to lead the band for a flat salary.

Later that year Wills’s body sang a second chorus of “I Can’t Go on This Way”: another heart attack.

Wills slowed his tempo. He gave up leadership of the Texas Playboys. But he continued to make personal appearances, performing every third night but traveling shorter distances. And he continued to record. In 1966 he recorded “A Big Ball in Cowtown” and “What’s Fort Worth?”

In 1968 he was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville.

In 1969 the Texas legislature passed a resolution honoring Wills “for his leadership in and his contributions to the field of country and western music.”

A few days later he suffered a stroke.

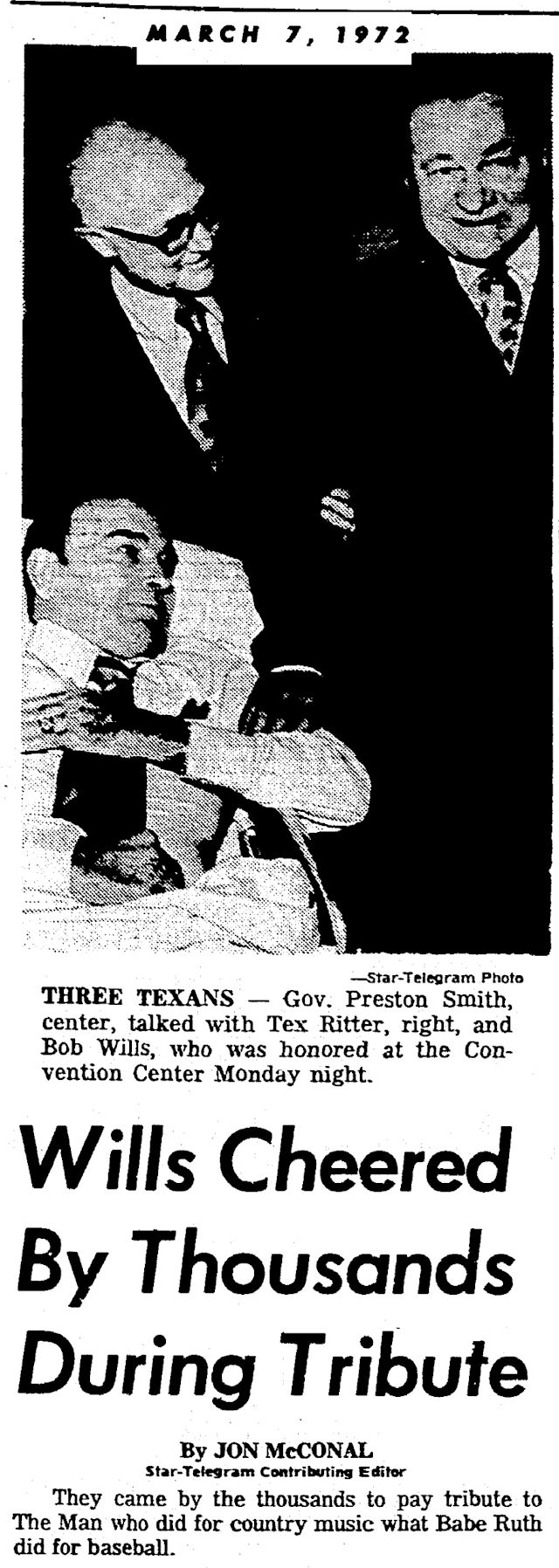

On Wills’s sixty-seventh birthday in 1972 six thousand people came to Tarrant County Convention Center to pay tribute to Wills. Wills, partially paralyzed, arrived in an ambulance and was brought on stage in a wheelchair.

On Wills’s sixty-seventh birthday in 1972 six thousand people came to Tarrant County Convention Center to pay tribute to Wills. Wills, partially paralyzed, arrived in an ambulance and was brought on stage in a wheelchair.

Governor Preston Smith was present to declare March 6 Country and Western Music Day in Texas in honor of Wills.

Performers at the tribute included Tex Ritter, Roy Acuff, Leroy Van Dyke, Merle Haggard, and Tompall Glaser.

Each time Wills hollered “Ahhh-haaaa”—however weakly—the audience roared its appreciation.

It was an emotional night for Wills, his fellow musicians, and fans. Some of those musicians, of course, also were fans. Haggard, born in 1937, and Glaser, born in 1933, as young musicians had idolized Wills.

Glaser said of the tribute: “I got choked up. I wanted to do such a strong job, and I saw him sitting there, and I didn’t think I’d ever be on stage with him, and I just choked up. Leon [McAuliffe] was crying, and the others were crying, and I started crying.”

In December 1973 Wills attempted what many of his friends had thought he could never do again: He was back in the studio, recording an album (originally entitled “What Makes Bob Holler?” but released as “Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys: For the Last Time”). The recording session in Dallas was a reunion of Wills and several of his Playboys. Also participating was Merle Haggard. On the first day, confined to a wheelchair, Wills was in the studio five hours.

In December 1973 Wills attempted what many of his friends had thought he could never do again: He was back in the studio, recording an album (originally entitled “What Makes Bob Holler?” but released as “Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys: For the Last Time”). The recording session in Dallas was a reunion of Wills and several of his Playboys. Also participating was Merle Haggard. On the first day, confined to a wheelchair, Wills was in the studio five hours.

The second day his wife Betty telephoned the studio to say he was too tired to record that day.

She described his reaction to the first day of recording: “He loved it. All but one thing. He was dissatisfied with his work. He felt he didn’t help out much.”

The next day Wills suffered another stroke, this time at his home on Trail Lake Drive.

The next day Wills suffered another stroke, this time at his home on Trail Lake Drive.

This one left him comatose.

And he stayed that way until his death in a Fort Worth nursing home in 1975.

And he stayed that way until his death in a Fort Worth nursing home in 1975.

Newspapers from Saskatchewan to Pensacola reported his death.

Newspapers from Saskatchewan to Pensacola reported his death.

James Robert Wills, musical maverick in the white Stetson hat, made one final trip between the two states that claim him. He was taken from Fort Worth “back to Tulsa” to be buried.

James Robert Wills, musical maverick in the white Stetson hat, made one final trip between the two states that claim him. He was taken from Fort Worth “back to Tulsa” to be buried.

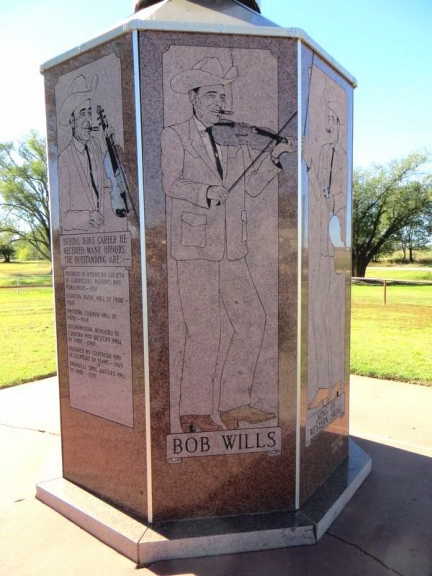

The town of Turkey honors its most famous son with a monument and an annual Bob Wills Day.

The town of Turkey honors its most famous son with a monument and an annual Bob Wills Day.

Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa still remembers.

Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa still remembers.

So does Fort Worth on its Texas Trail of Fame at the stockyards.

So does Fort Worth on its Texas Trail of Fame at the stockyards.

Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys (1951)

Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys on WFAA-TV’s Music Country Style (1963)

Waylon Jennings’s “Bob Wills Is Still the King” performed by . . . the Rolling Stones (2005)

A documentary film: The Birth & History of Western Swing (2021)