Cowtowners have always felt the need for speed. That need has naturally expressed itself in racing. And early on, in the nineteenth century, racing usually meant horses.

The first horse races were informal, perhaps just two cowboys racing from a line drawn in the sand to “that big sycamore tree down yonder” while a few spectators placed bets and passed a jug.

When did horse racing become more formal?

Historian Julia Kathryn Garrett in Fort Worth: A Frontier Triumph writes that by 1869 Fort Worth sportsmen had built the town’s first racetrack on today’s North Side near the river.

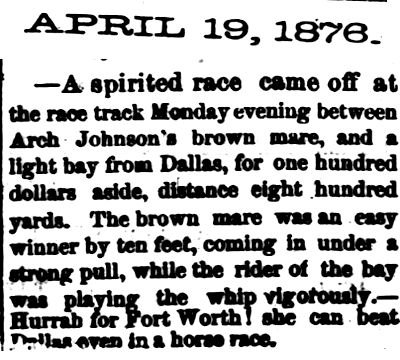

This Democrat report of 1876 refers to a race held at “the race track.” Arch Johnson owned a saloon and dance hall. (Note the dig at Dallas.)

This Democrat report of 1876 refers to a race held at “the race track.” Arch Johnson owned a saloon and dance hall. (Note the dig at Dallas.)

Garrett writes that after the Trinity River flooded the first track, in the 1870s a second track was built on higher ground: on “the west side of the Cold Springs Road about one half mile north of the Pioneers Rest Cemetery.”

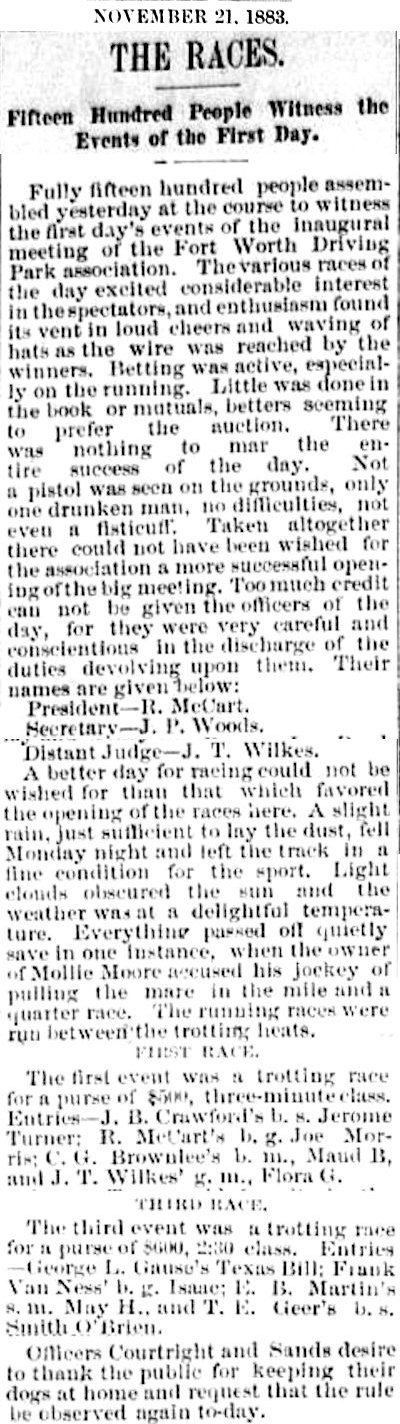

Not much is known about the first two tracks. But in 1883, near the site of the second track, a driving park opened as a place for people to race and bet.

Not much is known about the first two tracks. But in 1883, near the site of the second track, a driving park opened as a place for people to race and bet.

Robert McCart was president of the driving park association.

Taking part in the opening day races were undertakers George Gause and John T. Wilkes. Undertakers and horses were like business partners: Horses were the original transportation of funeral processions.

Races on opening day at the driving park were both dashes (with a jockey) and trots (with a driver in a cart).

Officer Jim Courtright thanked the spectators for not bringing their dogs.

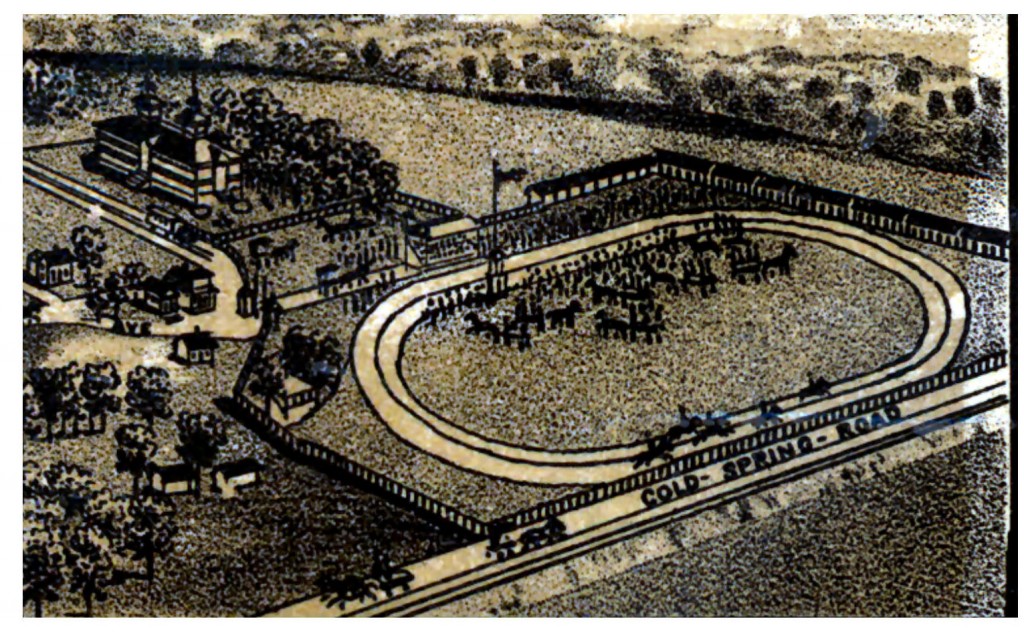

This detail of an 1886 bird’s-eye-view map of the Samuels Avenue area shows the driving park. That building with two cupolas northwest of the oval track was Rosedale Pavilion, Fort Worth’s first trolley park. Both facilities were served by a streetcar line.

This detail of an 1886 bird’s-eye-view map of the Samuels Avenue area shows the driving park. That building with two cupolas northwest of the oval track was Rosedale Pavilion, Fort Worth’s first trolley park. Both facilities were served by a streetcar line.

The driving park was not used just for equine events. In 1885 former tugboat captain James Dalton fought John Clow in a prize fight there. The park also hosted baseball games and shooting matches.

The driving park closed about 1889.

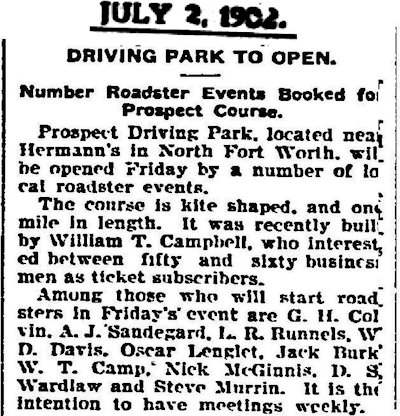

In 1902 Prospect Driving Park opened on the near North Side. By 1902 motor vehicles were still very rare, so the “roadsters” referred to in this clip were of the horse-drawn variety. (Note the mention of Steve Murrin.)

In 1902 Prospect Driving Park opened on the near North Side. By 1902 motor vehicles were still very rare, so the “roadsters” referred to in this clip were of the horse-drawn variety. (Note the mention of Steve Murrin.)

On November 6 A. J. Sandergard, who owned a chain of grocery stores, won the Prospect Cup in the trotting competition.

On November 6 A. J. Sandergard, who owned a chain of grocery stores, won the Prospect Cup in the trotting competition.

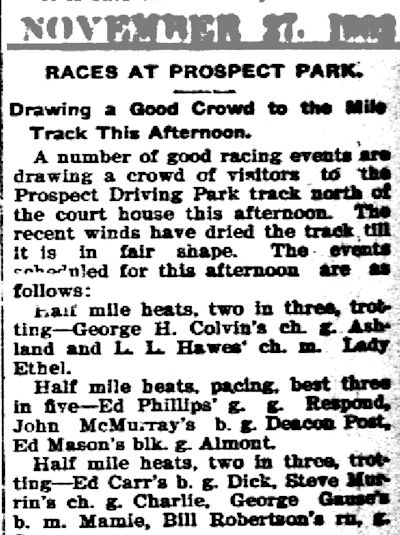

Races on November 17 included pacing and trotting. Note that undertaker George Gause again participated.

Races on November 17 included pacing and trotting. Note that undertaker George Gause again participated.

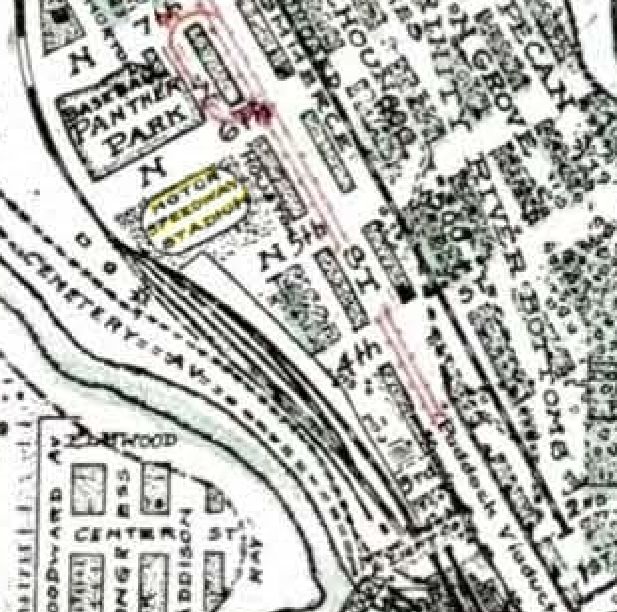

I have found only vague locations given for Prospect Park: “near Hermann’s in North Fort Worth” (Hermann Park was on North Main Street between Northwest 1st and 3rd streets) and “near the Cotton Belt depot” (the Cotton Belt yard also was west of North Main Street). Based on those clues and this 1925 map, I am convinced that Prospect Park was later the site of McGar Park (about 1907 to 1919) and finally the site of the “motor speedway stadium” for motorcycle racing in 1919.

I have found only vague locations given for Prospect Park: “near Hermann’s in North Fort Worth” (Hermann Park was on North Main Street between Northwest 1st and 3rd streets) and “near the Cotton Belt depot” (the Cotton Belt yard also was west of North Main Street). Based on those clues and this 1925 map, I am convinced that Prospect Park was later the site of McGar Park (about 1907 to 1919) and finally the site of the “motor speedway stadium” for motorcycle racing in 1919.

Prospect Park increasingly was used for nonequine events: shooting matches and amateur baseball.

Prospect Park increasingly was used for nonequine events: shooting matches and amateur baseball.

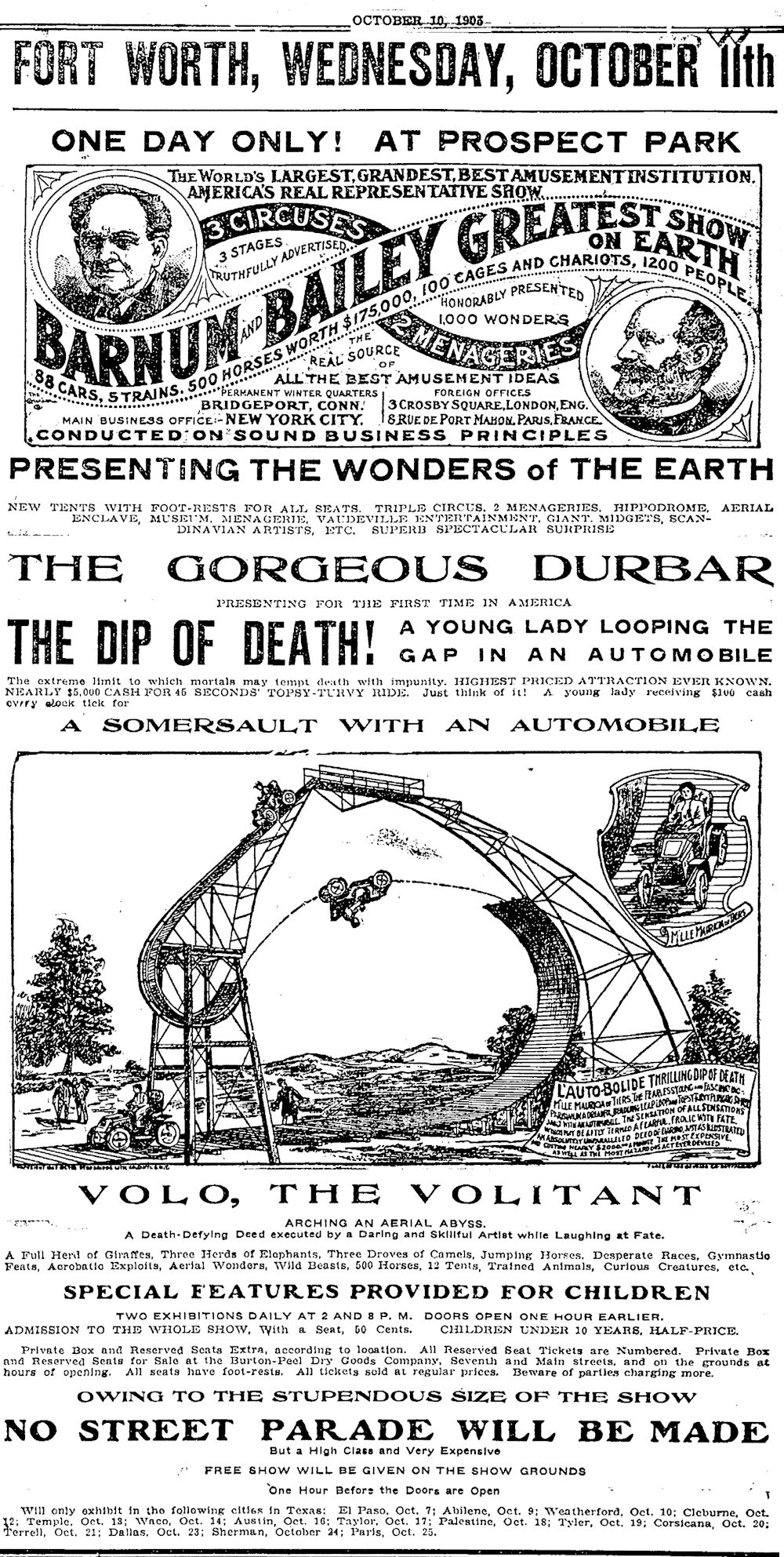

And even a circus.

And even a circus.

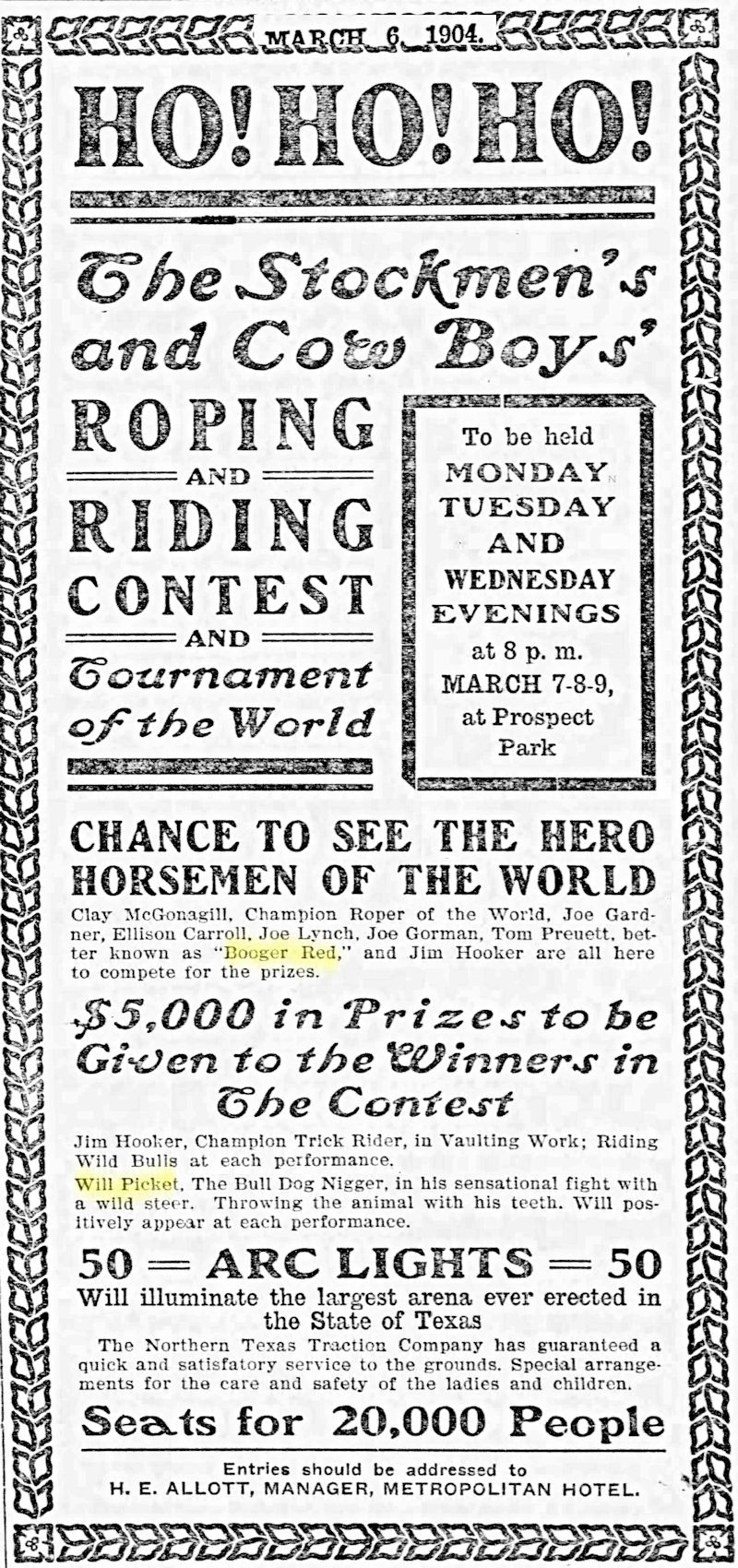

And rodeo events. On the bill were Booger Red and Bill Pickett.

And rodeo events. On the bill were Booger Red and Bill Pickett.

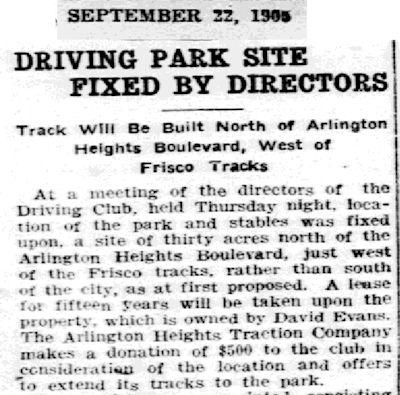

Perhaps such diversification came about because in 1905 Prospect Park got some competition: A new driving park was opened on the West Side just west of the Frisco railroad track.

Perhaps such diversification came about because in 1905 Prospect Park got some competition: A new driving park was opened on the West Side just west of the Frisco railroad track.

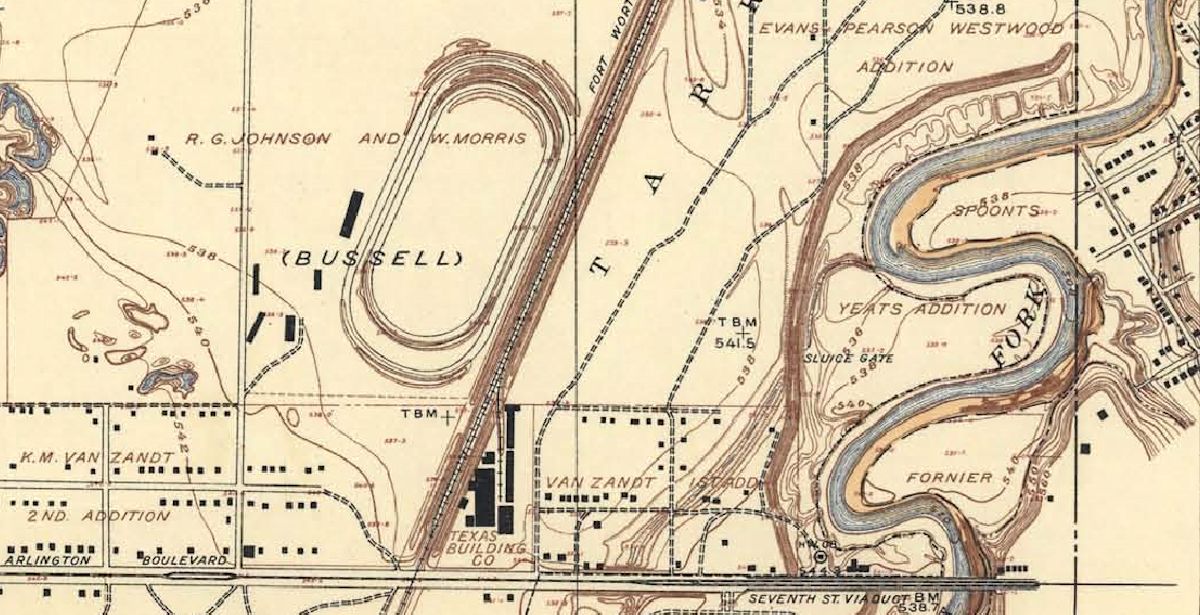

This 1915 map shows the oval track just north of where the Montgomery Ward store would open in 1928. The park could accommodate almost two thousand spectators.

This 1915 map shows the oval track just north of where the Montgomery Ward store would open in 1928. The park could accommodate almost two thousand spectators.

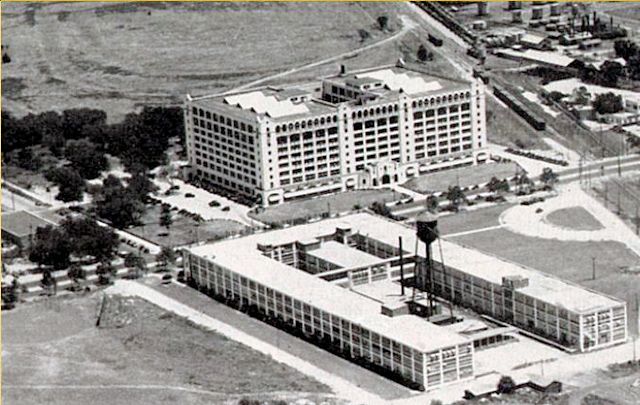

Even though the track had been closed for years by the time this photo was taken in 1930, the oval can still be seen behind the Montgomery Ward store. The building in the foreground is the 1916 Chevrolet plant.

Even though the track had been closed for years by the time this photo was taken in 1930, the oval can still be seen behind the Montgomery Ward store. The building in the foreground is the 1916 Chevrolet plant.

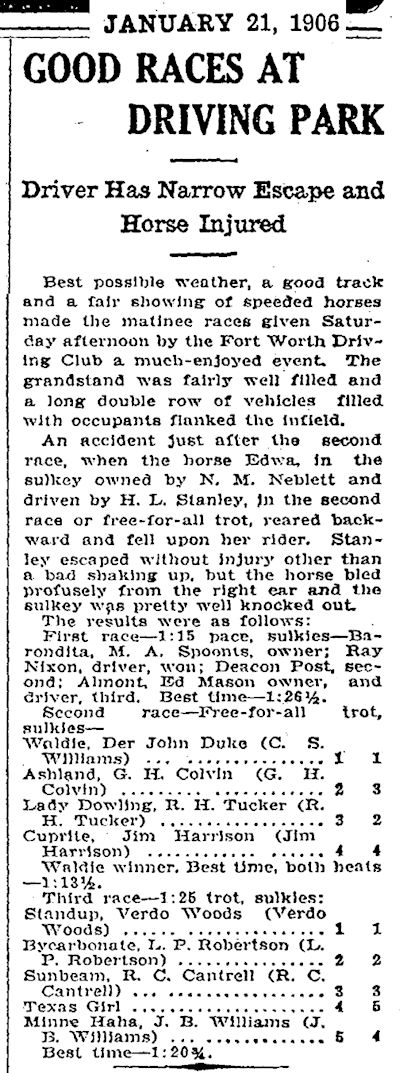

As with the 1883 and 1902 driving parks, note the participation of an undertaker: Louis P. Robertson.

As with the 1883 and 1902 driving parks, note the participation of an undertaker: Louis P. Robertson.

Like the earlier driving parks, the driving park on West 7th Street offered more sports than just horse racing.

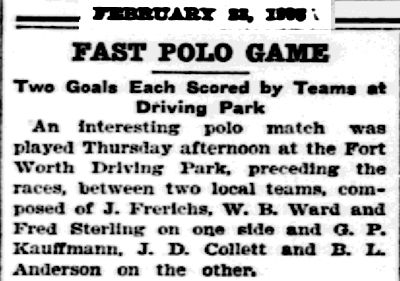

Such as polo. Among members of Fort Worth’s polo club were cotton brokers Herman Frerichs and Bernie L. Anderson of Quality Hill.

Such as polo. Among members of Fort Worth’s polo club were cotton brokers Herman Frerichs and Bernie L. Anderson of Quality Hill.

The West 7th Street driving park also hosted baseball, tennis, rodeo, shooting contests, casting contests, and baby contests.

And at least one head-on locomotive collision. In 1907 “Head-On Joe” Connolly, who staged more than seventy such collisions across the country, came to town with two locomotives. More than twenty thousand people watched the two iron behemoths crash into each other at forty miles per hour.

And at least one head-on locomotive collision. In 1907 “Head-On Joe” Connolly, who staged more than seventy such collisions across the country, came to town with two locomotives. More than twenty thousand people watched the two iron behemoths crash into each other at forty miles per hour.

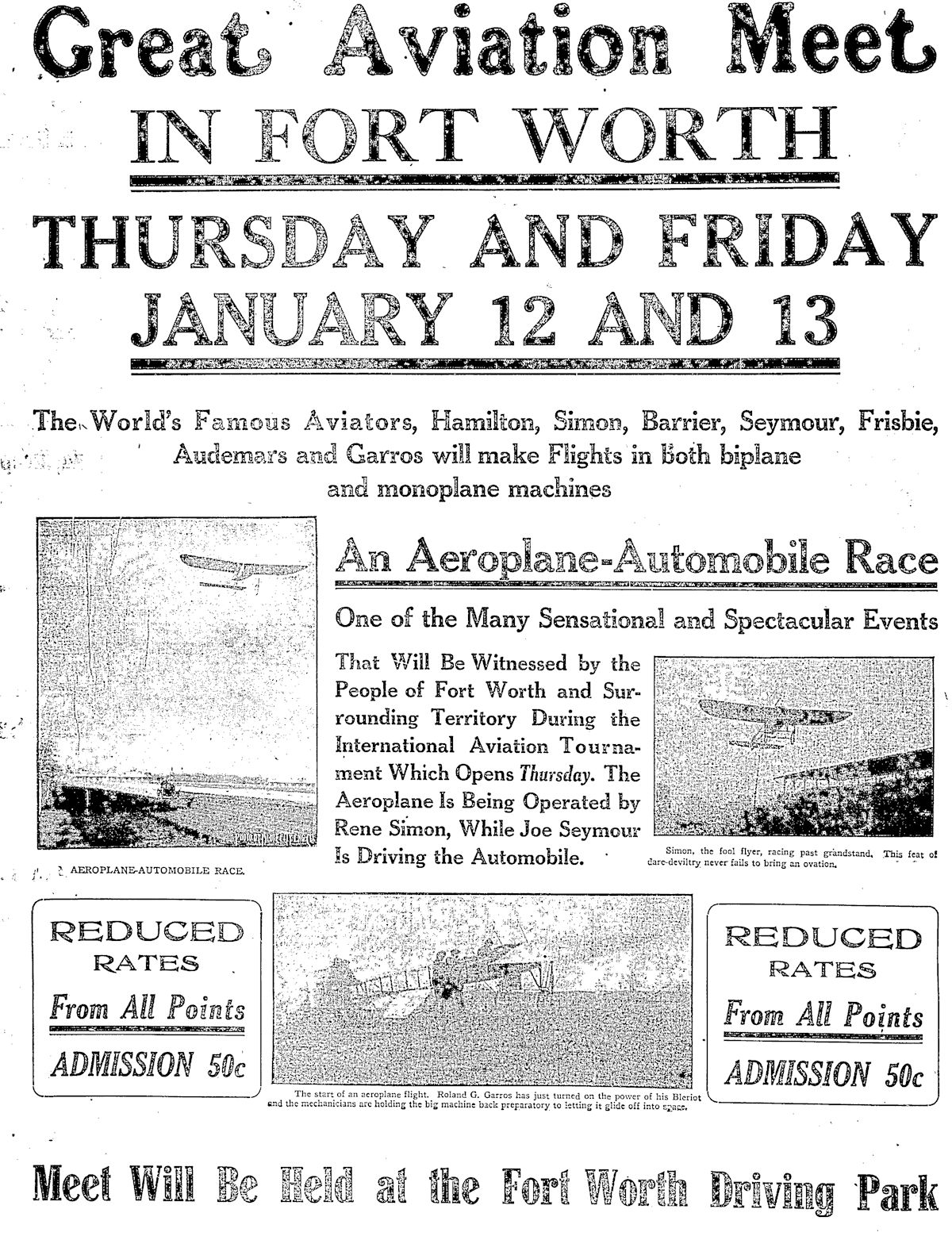

Four years later, in January 1911 an air show at the driving park featured the French daredevil Roland Garros, who made Fort Worth’s first powered flight during that show.

Four years later, in January 1911 an air show at the driving park featured the French daredevil Roland Garros, who made Fort Worth’s first powered flight during that show.

In 1914 the driving park hosted motorcycle races.

In 1914 the driving park hosted motorcycle races.

And auto races.

And auto races.

The driving park closed about 1920.

On the east side of town William Bailey Fishburn had a horse race track. This 1919 article says pacing and trotting races would be held at Fishburn’s track. “Short ship” apparently refers to the distance that horses were transported to races by rail.

On the east side of town William Bailey Fishburn had a horse race track. This 1919 article says pacing and trotting races would be held at Fishburn’s track. “Short ship” apparently refers to the distance that horses were transported to races by rail.

![]() This is a section of a 1920 map of the East Side. That oval near the center was Fishburn’s track. Fishburn bought those twenty acres in 1917 and built a “fine new home” and a stable for thirty-six horses. The farm was just east of Ayers Avenue between Lancaster Avenue and the interurban track and the Texas & Pacific track.

This is a section of a 1920 map of the East Side. That oval near the center was Fishburn’s track. Fishburn bought those twenty acres in 1917 and built a “fine new home” and a stable for thirty-six horses. The farm was just east of Ayers Avenue between Lancaster Avenue and the interurban track and the Texas & Pacific track.

This map detail has several stories to tell beyond Fishburn’s racetrack. See the circle on the map labeled “Tandy Lake Stop” interurban stop north of Polytechnic Cemetery? That unlabeled squiggle just to the right of the word “Stop” probably was what was left of Tandy Lake, which had been a popular recreation area since the late nineteenth century but was greatly reduced in area by 1920. The lake was just south of Lancaster Avenue (“Pike” on map) and the interurban line and just west of Ayers Avenue. Today runoff that once fed the lake is channeled west to Sycamore Creek.

What had begun at Polytechnic College in 1891 by 1920 was Texas Woman’s College.

And see the dashed line zigzagging east along the “Pike” and then southeast along the Texas & Pacific track and then south along the cemetery and then east on Avenue E and then south again on Ayers Avenue? That was the city limit of Polytechnic Heights in 1920 before annexation by Fort Worth in 1922.

And note that via connections on the interurban, you could travel from Fort Worth (or Cleburne) to Sherman, Corsicana, and Waco.

![]()

![]() Remember the Fishburn chain of dry cleaning stores? Same guy. Fishburn had been in the dyeing and cleaning business in Fort Worth since 1901. William Bailey Fishburn died in 1951.

Remember the Fishburn chain of dry cleaning stores? Same guy. Fishburn had been in the dyeing and cleaning business in Fort Worth since 1901. William Bailey Fishburn died in 1951.

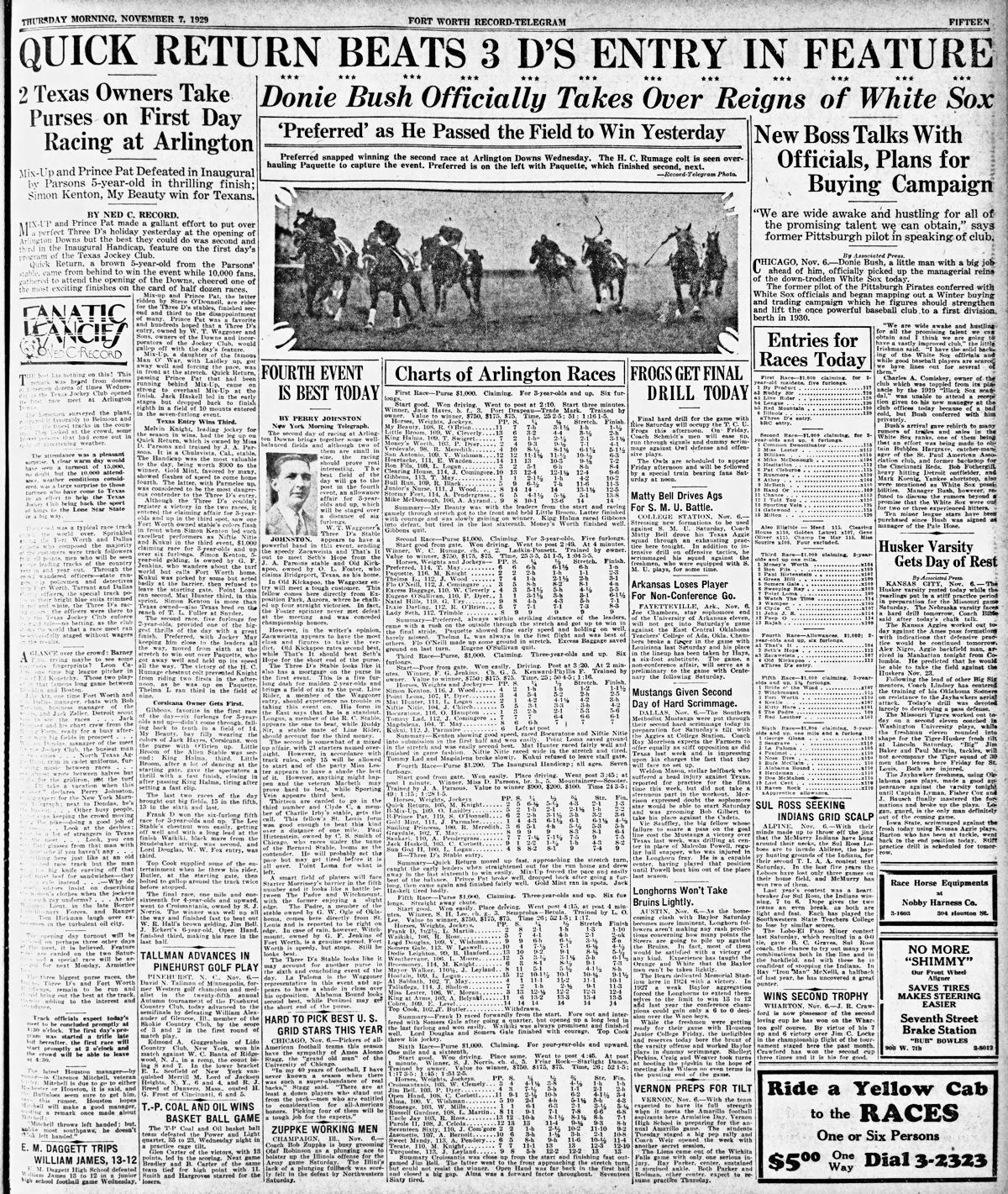

Another prominent horseman was oil and cattle millionaire W. T. Waggoner. He raised thoroughbred horses at his DDD stock farm in Arlington. In 1929 Waggoner gambled and built Arlington Downs racetrack on his farm, even though betting on horse racing was illegal in Texas at the time. The track opened on November 6. (In the featured race a horse from Waggoner’s stock farm finished second.)

Waggoner lobbied the state legislature to legalize betting. And his gamble paid off. In 1933 parimutuel betting became legal.

Fast company: From left, Frank Hawks, W. T. Waggoner, Will Rogers, and Amon Carter, early 1930s, at Arlington Downs. Frank Hawks was a record-setting aviator known as the “fastest airman in the world.” (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

Fast company: From left, Frank Hawks, W. T. Waggoner, Will Rogers, and Amon Carter, early 1930s, at Arlington Downs. Frank Hawks was a record-setting aviator known as the “fastest airman in the world.” (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

Arlington Downs was convenient to the interurban and the Bankhead Highway, near today’s intersection of Division Street and Highway 360.

The course had a capacity of twenty thousand fans. The track was a mile and a quarter long.

Waggoner was eighty-two in 1933 when he attended the first parimutuel race at his track. Paralyzed on one side, he was wrapped in a blanket as he sat in an automobile and listened as the roar of the crowd drowned out the pounding of hoofbeats.

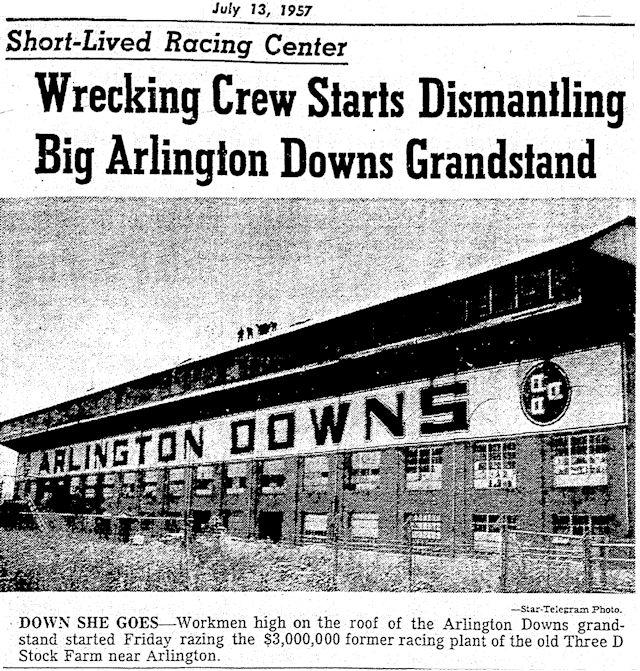

Waggoner died the next year. In 1937 the Texas legislature banned parimutuel betting, and the track soon closed. In 1942 Arlington Downs became the site of the motor pool of the Army’s Eighth Corps Area.

Great Southwest Corporation bought the property in 1956 from Waggoner son E. Paul.

Demolition of Arlington Downs began in 1957.

Demolition of Arlington Downs began in 1957.

Today all that is left of Arlington Downs is this concrete fountain engraved with jockeys on horses at the corner of Commerce Drive and Six Flags Drive.

Today all that is left of Arlington Downs is this concrete fountain engraved with jockeys on horses at the corner of Commerce Drive and Six Flags Drive.