Early in the twentieth century America put the pedal to the metal and moved from the Age of the Horse to the Age of Horsepower. Likewise, Cowtown made the transition from horse racing (see The Need for Speed (Part 1): Hooves) to motor racing. For example, the West 7th Street driving park, which had been built for horse racing, began to host motorcycle racing and auto racing.

Soon tracks were built specifically for motor racing.

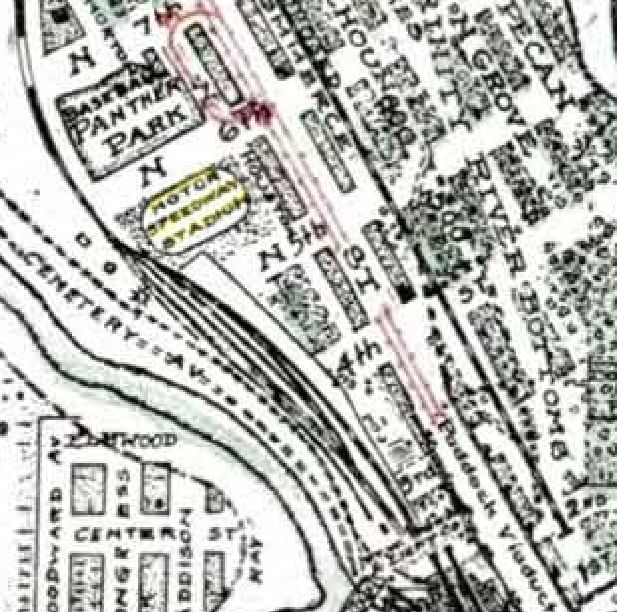

One of the first was the motordrome just south of Panther Park. The motordrome was built where first Prospect Park and then McGar Park had stood from about 1902 to 1919.

One of the first was the motordrome just south of Panther Park. The motordrome was built where first Prospect Park and then McGar Park had stood from about 1902 to 1919.

The motordrome track was a quarter-mile in circumference, made of wood, and banked at an angle of fifty-two degrees. The track was built by Jack Prince, the most famous of motordrome promoters.

When the Fort Worth motordrome opened in 1919 stars of the sport, such as world champion Ray Creviston, drew large crowds.

The motorcycles ridden by motordrome racers were no-frills land rockets. They were capable of speeds in excess of ninety miles an hour on a banked track. They had no brakes, no transmission. Riders used the throttle and engine load to slow their motorcycles. The motorcycles had no starter. They had to be towed by another motorcycle to start their engine.

The sport was dangerous and well before 1919 had been plagued with accidents in which racers and spectators had been killed, especially on the short tracks—such as Fort Worth’s. Such short tracks came to be known as “murderdromes.”

Finally, on July 18, 1919—just two days after the Fort Worth motordrome had opened—the Motorcycle and Allied Trades Association, which regulated motorcycle racing, withdrew its sanctioning of board tracks shorter than one mile. MATA also announced that it would outlaw racers who competed in such nonsanctioned “murderdromes.”

The magazine singled out Jack Prince and the “disastrous financial and physical effects” of the short tracks he had built and continued to build.

Fort Worth’s motordrome did not reopen for the 1920 season.

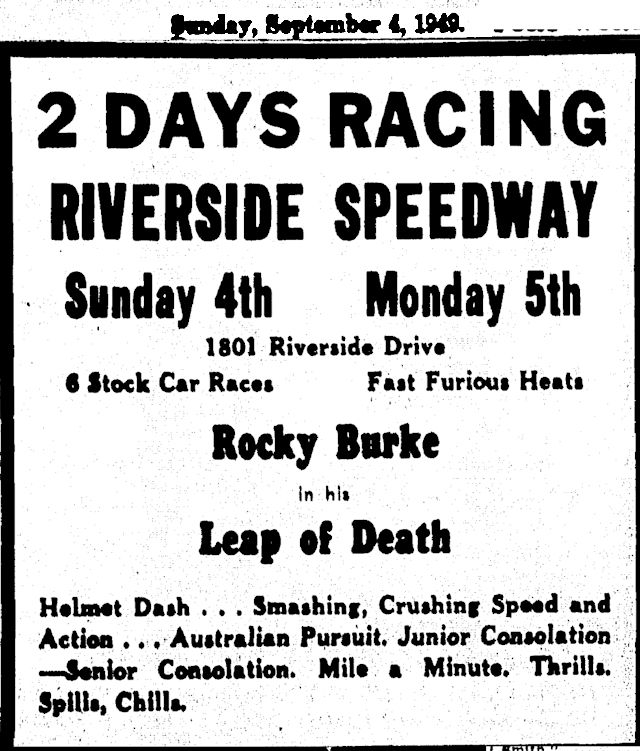

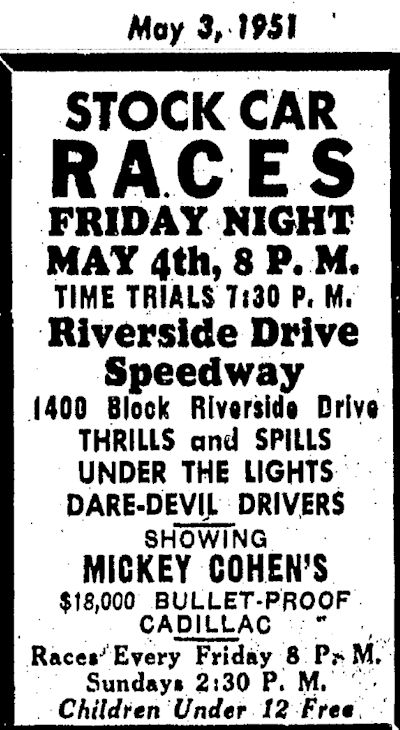

Fast-forward thirty years. In 1949 Riverside Drive Speedway, a quarter-mile oval dirt track of the Texas Stock Car Racing Association, opened on Riverside Drive north of Lancaster Avenue.

Fast-forward thirty years. In 1949 Riverside Drive Speedway, a quarter-mile oval dirt track of the Texas Stock Car Racing Association, opened on Riverside Drive north of Lancaster Avenue.

The track was managed by J. W. Jenkins, head of the racing association.

This 1952 aerial photo shows the oval speedway in an area that would soon undergo great change. The Trinity River floodway project would straighten the channel of the river from east to west, orphaning part of the old channel and part of Sycamore Creek.

This 1952 aerial photo shows the oval speedway in an area that would soon undergo great change. The Trinity River floodway project would straighten the channel of the river from east to west, orphaning part of the old channel and part of Sycamore Creek.

The turnpike soon would be built parallel to the new river channel. And Sylvania Street and Riverside Drive would be connected north of the speedway.

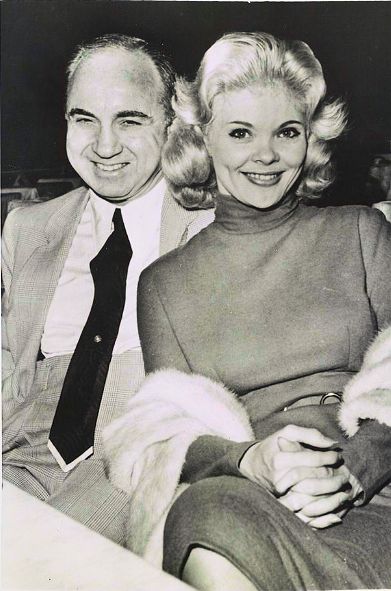

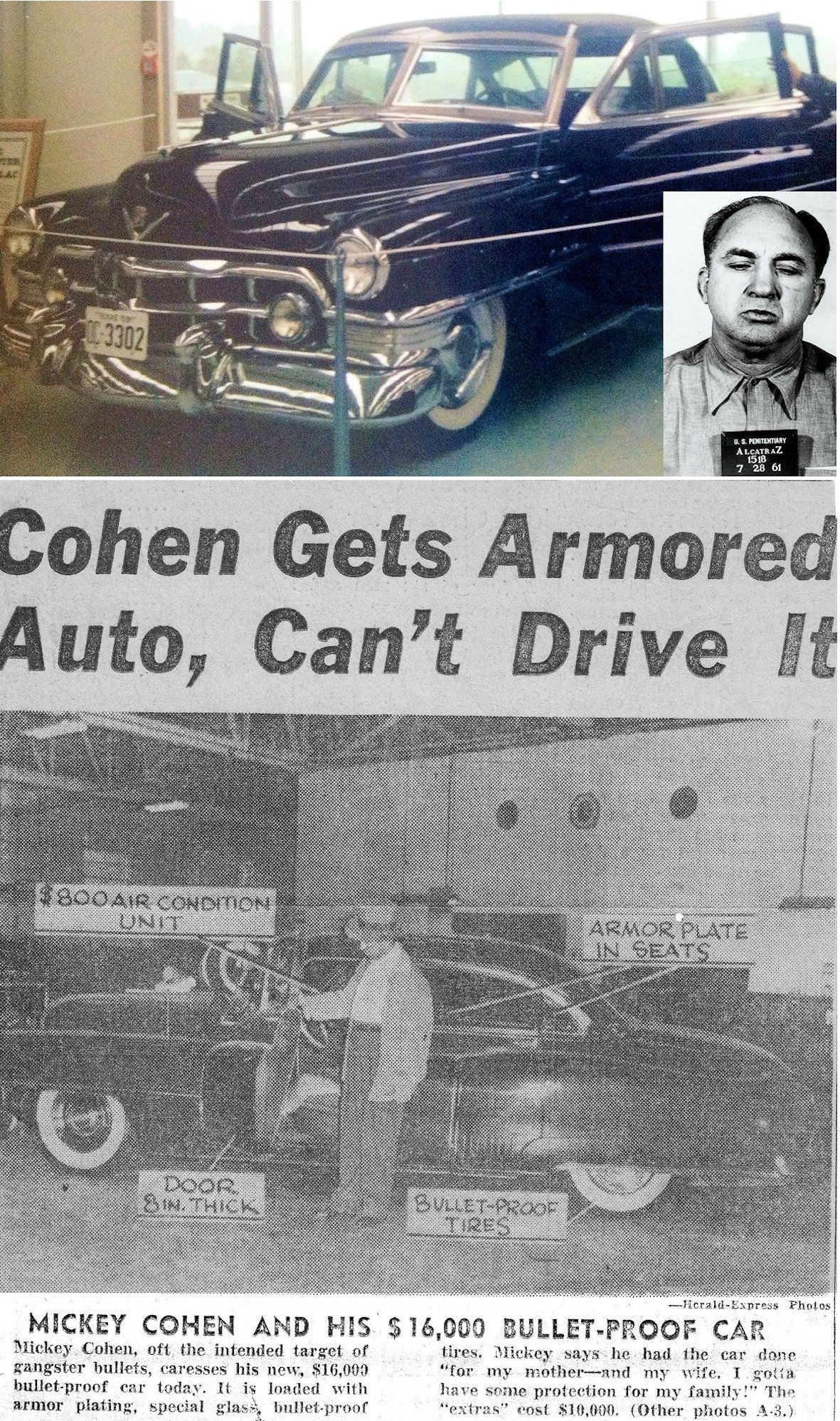

Meanwhile, out in California mobster Mickey Cohen (once romantically linked with Candy Barr, top photo) had paid $16,000 ($162,000 today) for a bulletproof 1950 Cadillac (memo to Frank Kent). Then Cohen was told he could not drive the car in California because he had neglected to get a permit from the California Highway Patrol to operate an armored vehicle. (Photos from Wikipedia; clip from the Los Angeles Herald-Express.)

Meanwhile, out in California mobster Mickey Cohen (once romantically linked with Candy Barr, top photo) had paid $16,000 ($162,000 today) for a bulletproof 1950 Cadillac (memo to Frank Kent). Then Cohen was told he could not drive the car in California because he had neglected to get a permit from the California Highway Patrol to operate an armored vehicle. (Photos from Wikipedia; clip from the Los Angeles Herald-Express.)

In 1951 Jenkins and his racing association paid $12,000 ($108,000 today) to Cohen for the bulletproof Cadillac. Jenkins displayed the car at the speedway. He had even offered Cohen a $500 bonus if Cohen would drive the Caddy around the track for a paying crowd. But Cohen was busy packing his bags to go to prison for tax evasion.

In 1951 Jenkins and his racing association paid $12,000 ($108,000 today) to Cohen for the bulletproof Cadillac. Jenkins displayed the car at the speedway. He had even offered Cohen a $500 bonus if Cohen would drive the Caddy around the track for a paying crowd. But Cohen was busy packing his bags to go to prison for tax evasion.

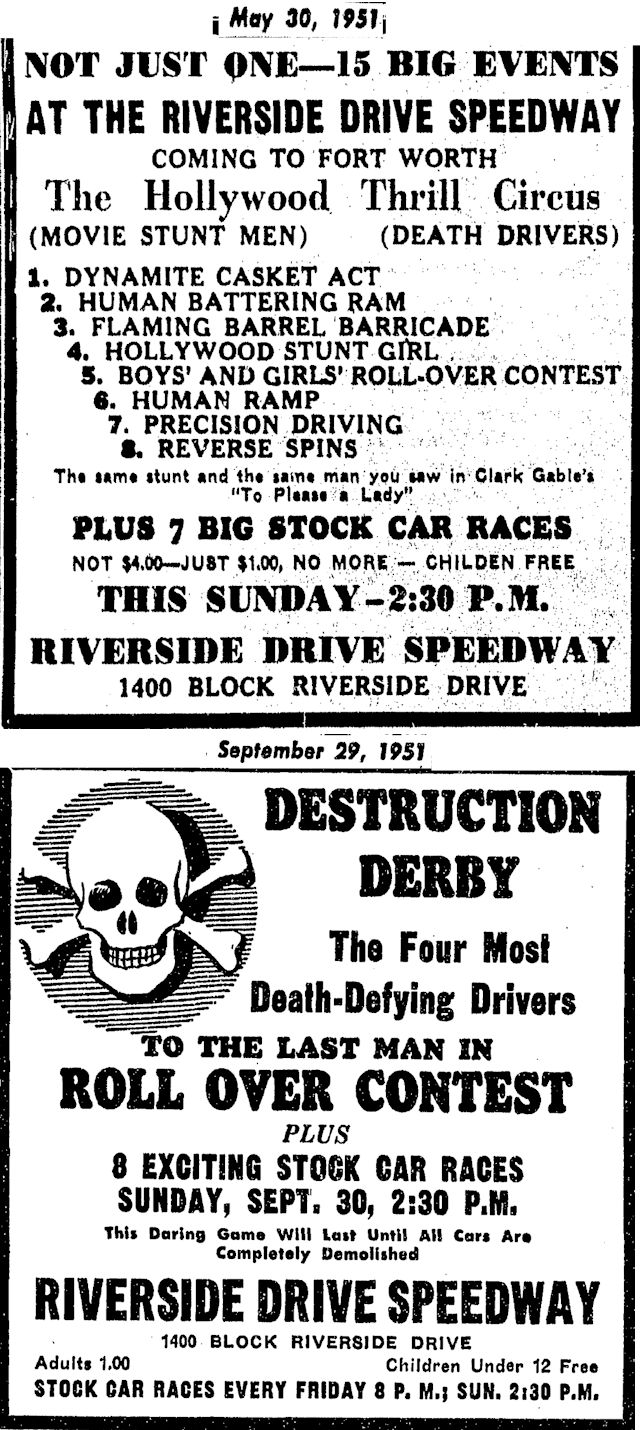

“Dynamite Casket Act”! “Destruction Derby”!

“Dynamite Casket Act”! “Destruction Derby”!

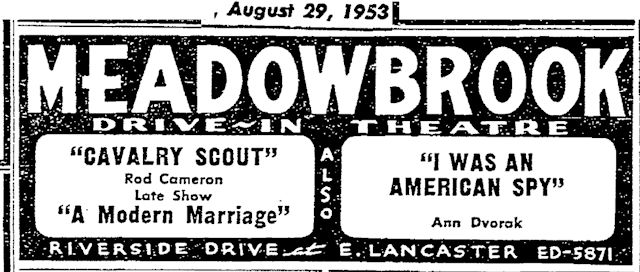

The Riverside Drive Speedway did not last long. In the summer of 1953 the Meadowbrook drive-in theater opened on the site.

The Riverside Drive Speedway did not last long. In the summer of 1953 the Meadowbrook drive-in theater opened on the site.

Fast-forward seven years. In the last half of the twentieth century, even if you didn’t know a funny car from a funny bone, if you owned a radio you knew about this racetrack:

Fast-forward seven years. In the last half of the twentieth century, even if you didn’t know a funny car from a funny bone, if you owned a radio you knew about this racetrack:

“Sunday, Sunday, Sunday! . . . Be there!”

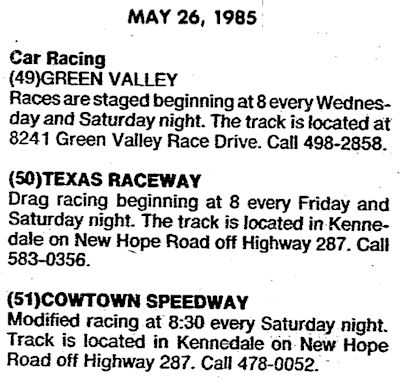

The commercials for Green Valley Raceway were not subtle. But then neither is a 1,500-horsepower top fuel dragster.

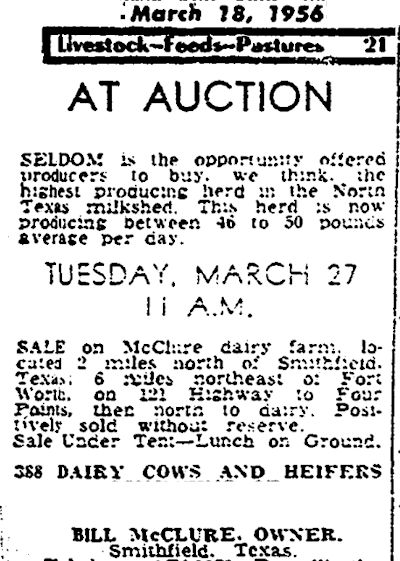

Green Valley Raceway, famed showcase of the fastest and loudest of land sports, began in a pokey and placid setting: Bill McClure’s Rockwood Farm dairy.

McClure had been a rodeo rider in the 1920s. But, he told the Star-Telegram in 1965, he quit “because I couldn’t win” and started a dairy. In 1956 he heard about some nightly noise on the old Denton Highway. He investigated one night and found dozens of dragsters holding an impromptu race.

McClure had been a rodeo rider in the 1920s. But, he told the Star-Telegram in 1965, he quit “because I couldn’t win” and started a dairy. In 1956 he heard about some nightly noise on the old Denton Highway. He investigated one night and found dozens of dragsters holding an impromptu race.

McClure “decided to build those boys a place to race,” he recalled.

He sold his cows and “threw it all down on asphalt,” paving a three thousand-foot dragstrip.

In February 1960 McClure announced that his former dairy was now a dragstrip and would host its first race. He learned how to wave a starting flag, assigned his wife to fry hamburgers in a hastily built shack, and waited.

Six thousand people showed up on race day, and suddenly the McClures needed a lot more hamburger.

As the track grew in popularity McClure increased the seating and parking capacity, built a bridge over the dragstrip, built a picnic area and a trophy room, and added a 1.5-mile course for road races. The property eventually covered 150 acres.

“I guess I’d better say I like to watch the cars race,” McClure said in 1965, “but really I don’t know much about how they work. At first I barely knew a Ford from a Chevy. I knew nothing about how race cars were classified.”

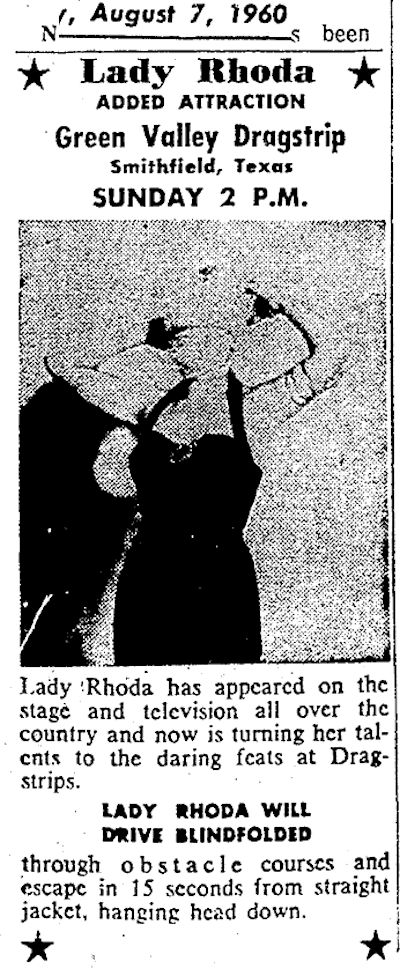

An “added attraction” at Green Valley in 1960 was Lady Rhoda, who drove through an obstacle course while blindfolded and wearing a straitjacket.

An “added attraction” at Green Valley in 1960 was Lady Rhoda, who drove through an obstacle course while blindfolded and wearing a straitjacket.

In 1972 McClure sold Green Valley Dragway to a company that did know a thing or two about race cars. Bill Hielscher, a former professional racer, became the race coordinator.

In 1972 McClure sold Green Valley Dragway to a company that did know a thing or two about race cars. Bill Hielscher, a former professional racer, became the race coordinator.

But Hielscher was not just the race coordinator for long.

But Hielscher was not just the race coordinator for long.

He soon bought the dragstrip, and it became “Green Valley Race City.”

In the 1970s, if it was fast, it raced at Green Valley: funny cars, sports cars, rail dragsters, stock cars, cars with jet engines, motorcycles, even souped-up go-carts.

Among the races were those sanctioned by Trans-Am Series, Sports Car Club of America, Can-Am Series, American Motorcycle Association, National Hot Rod Association, and American Hot Rod Association.

Stars of the sport who raced at Green Valley included Parnelli Jones, Dan Gurney, “Big Daddy” Don Garlits, and Gene Snow.

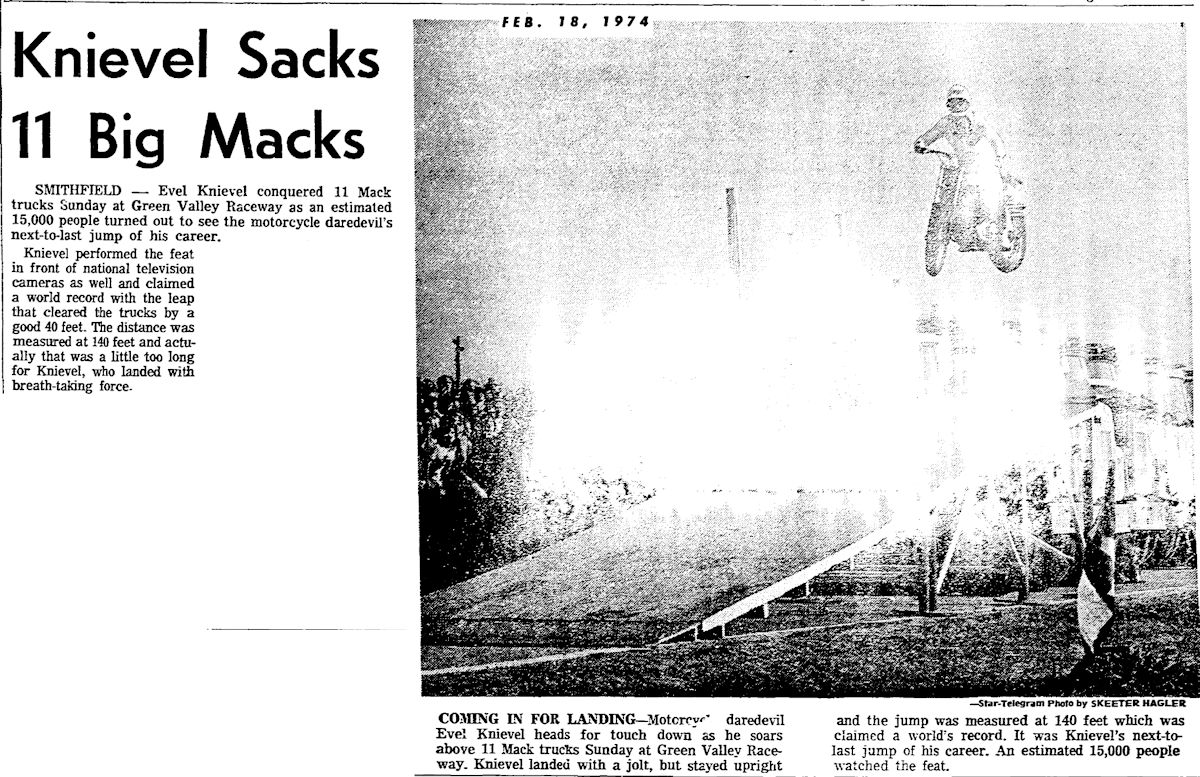

In 1974 fifteen thousand fans gathered at Green Valley to watch Evel Knievel jump 140 feet over eleven Mack trucks. He cleared the trucks with forty feet to spare. The jump was broadcast on national television.

In 1974 fifteen thousand fans gathered at Green Valley to watch Evel Knievel jump 140 feet over eleven Mack trucks. He cleared the trucks with forty feet to spare. The jump was broadcast on national television.

Green Valley closed in 1986. By then, Hielscher said, the track had hosted five thousand races.

Green Valley closed in 1986. By then, Hielscher said, the track had hosted five thousand races.

Some of the last to race at Green Valley were the children of the first to race at Green Valley.

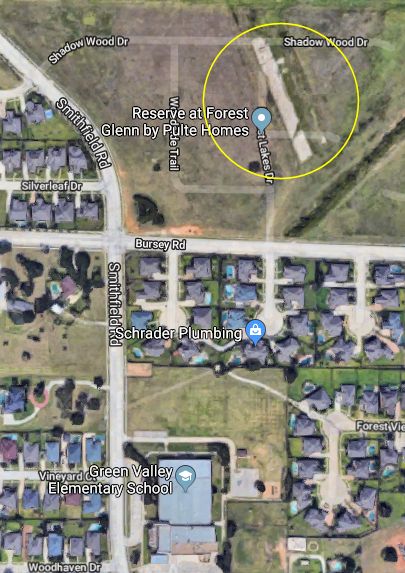

Today reading and writing have replaced revving and roaring: Green Valley Elementary School and a housing addition stand on the site of the racetrack.

Today reading and writing have replaced revving and roaring: Green Valley Elementary School and a housing addition stand on the site of the racetrack.

Until about six years ago part of the strip remained.

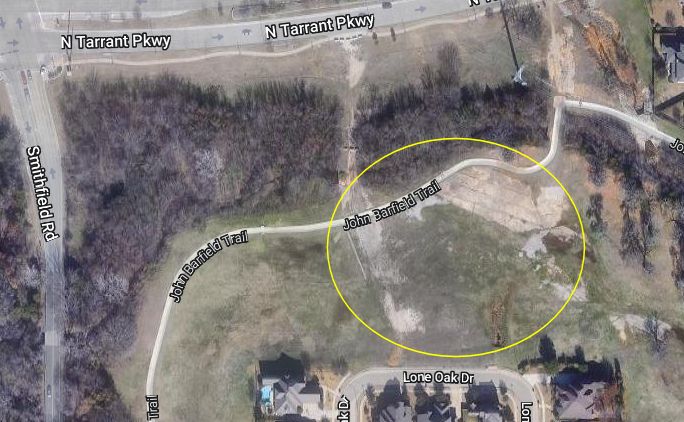

Today some concrete remains along John Barfield Trail at what old aerial photos show was the north end of the Green Valley complex.

Today some concrete remains along John Barfield Trail at what old aerial photos show was the north end of the Green Valley complex.

Watch silent home movie footage of Green Valley on YouTube.

Hear a Green Valley radio commercial.

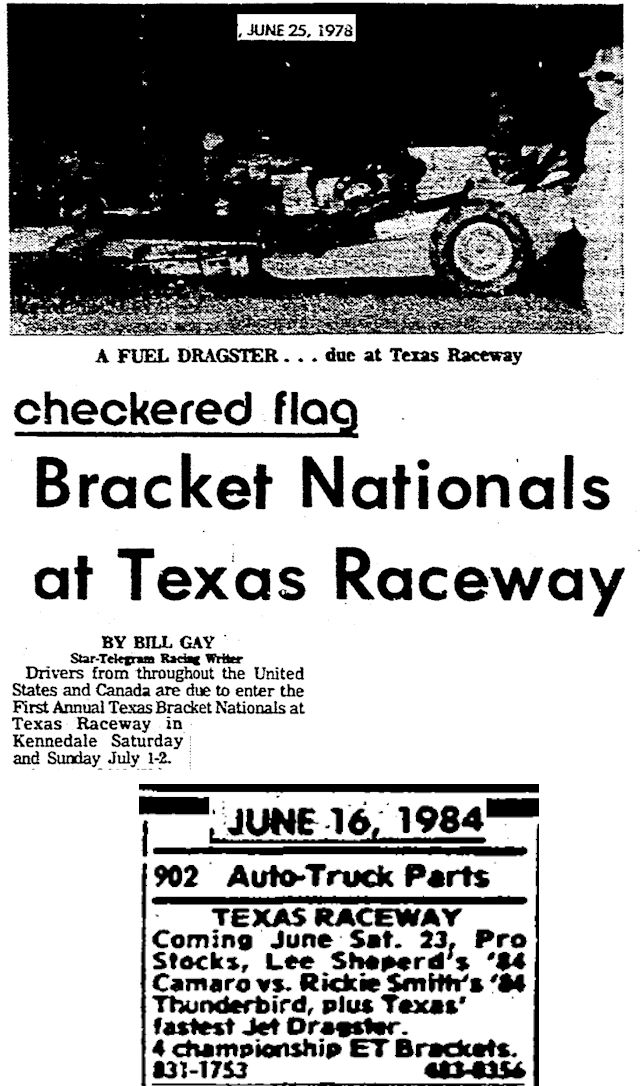

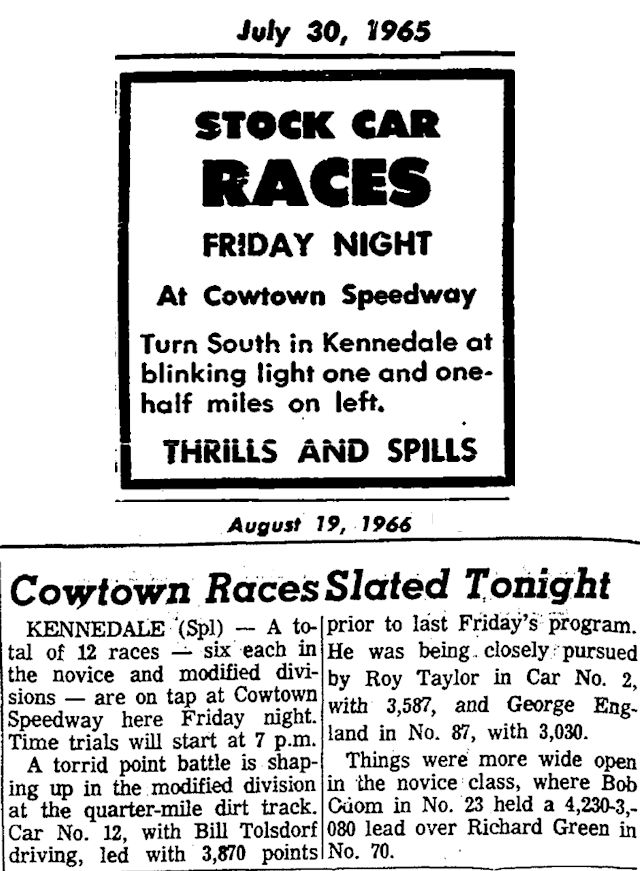

Green Valley may have gotten all the headlines, but twenty miles to the south, twenty years ago Kennedale was the mecca of motion.

Green Valley may have gotten all the headlines, but twenty miles to the south, twenty years ago Kennedale was the mecca of motion.

Three motor racing courses were located within a half-mile of each other just south of Kennedale: Texas Raceway, Cowtown Speedway, and Kennedale Speedway Park.

Three motor racing courses were located within a half-mile of each other just south of Kennedale: Texas Raceway, Cowtown Speedway, and Kennedale Speedway Park.

Texas Raceway, a dragstrip, operated from 1961 to 2017.

Texas Raceway, a dragstrip, operated from 1961 to 2017.

Just down the road, Cowtown Speedway was an oval track that hosted weekend races for minor classes such as dwarf cars, sprint cars, stock cars, and go-karts. It opened about 1965 and closed in 2012.

Just down the road, Cowtown Speedway was an oval track that hosted weekend races for minor classes such as dwarf cars, sprint cars, stock cars, and go-karts. It opened about 1965 and closed in 2012.

Kennedale Speedway Park, a quarter-mile dirt oval track built in the 1990s, still operates.

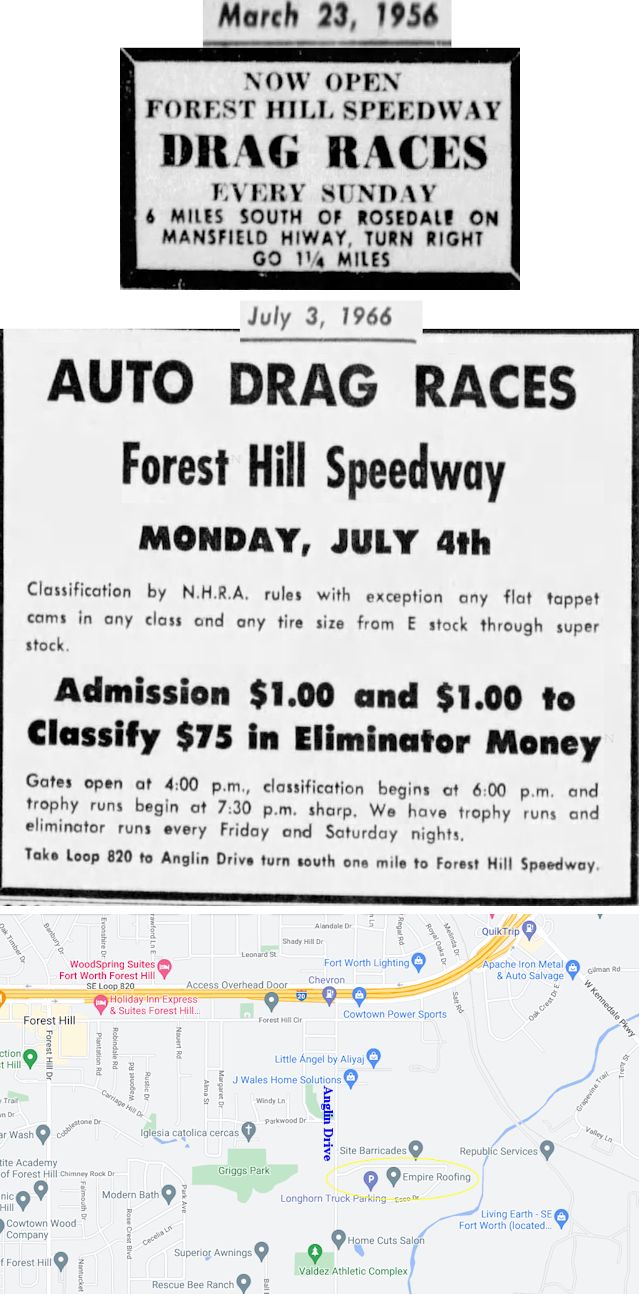

And in Forest Hill on Anglin Drive south of Loop 820/Interstate 20, Forest Hill Speedway operated from 1956 into the 1960s.

And in Forest Hill on Anglin Drive south of Loop 820/Interstate 20, Forest Hill Speedway operated from 1956 into the 1960s.

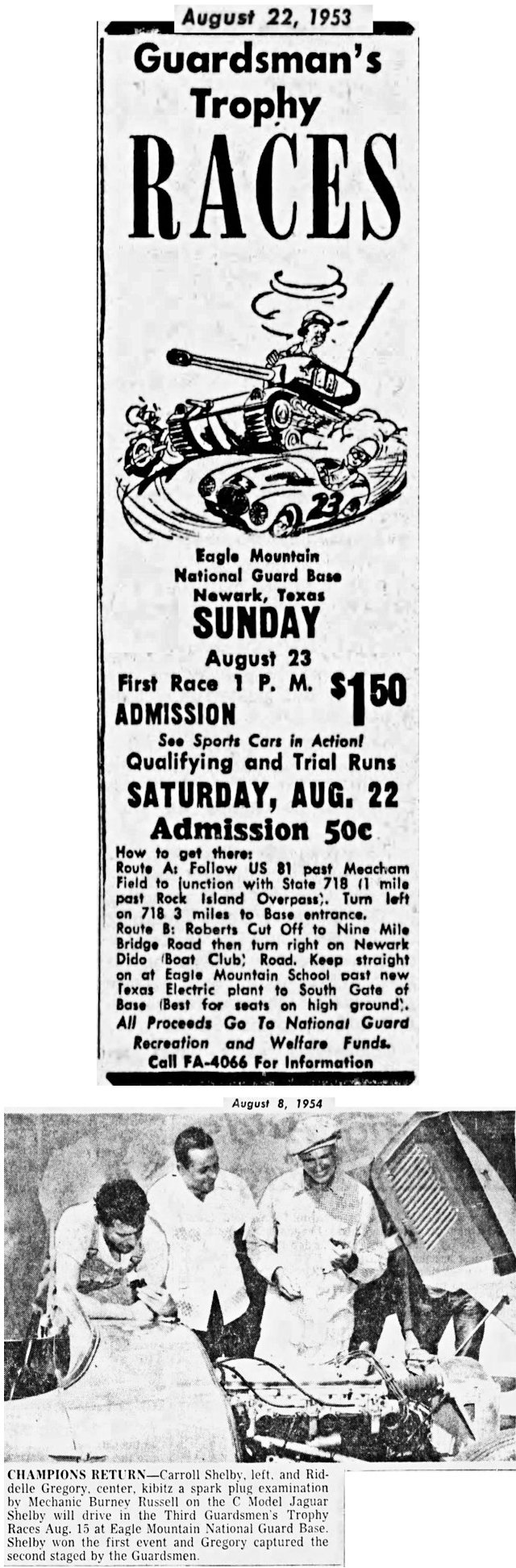

Auto races were also held at the National Guard base at Eagle Mountain Lake. Motorcycle races were held at the base after it was bought by Kenneth Copeland.

Auto races were also held at the National Guard base at Eagle Mountain Lake. Motorcycle races were held at the base after it was bought by Kenneth Copeland.

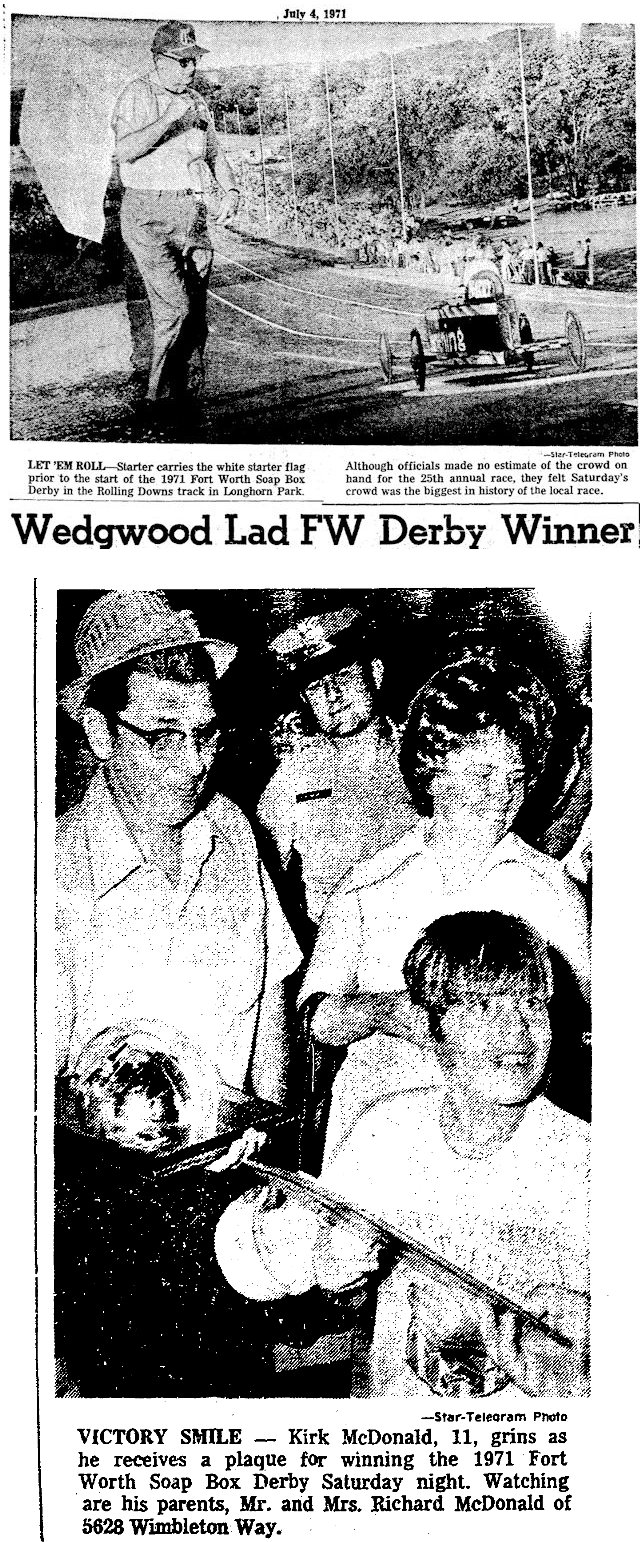

At the other end of the spectrum in both sound and fury was a racetrack near Lake Benbrook. Rolling Downs was the last home of Fort Worth’s soap box derby, where the race cars were powered by gravity, not high-octane fuel. The derby began in 1946. At first the races were held on Lancaster Avenue at the Will Rogers complex.

At the other end of the spectrum in both sound and fury was a racetrack near Lake Benbrook. Rolling Downs was the last home of Fort Worth’s soap box derby, where the race cars were powered by gravity, not high-octane fuel. The derby began in 1946. At first the races were held on Lancaster Avenue at the Will Rogers complex.

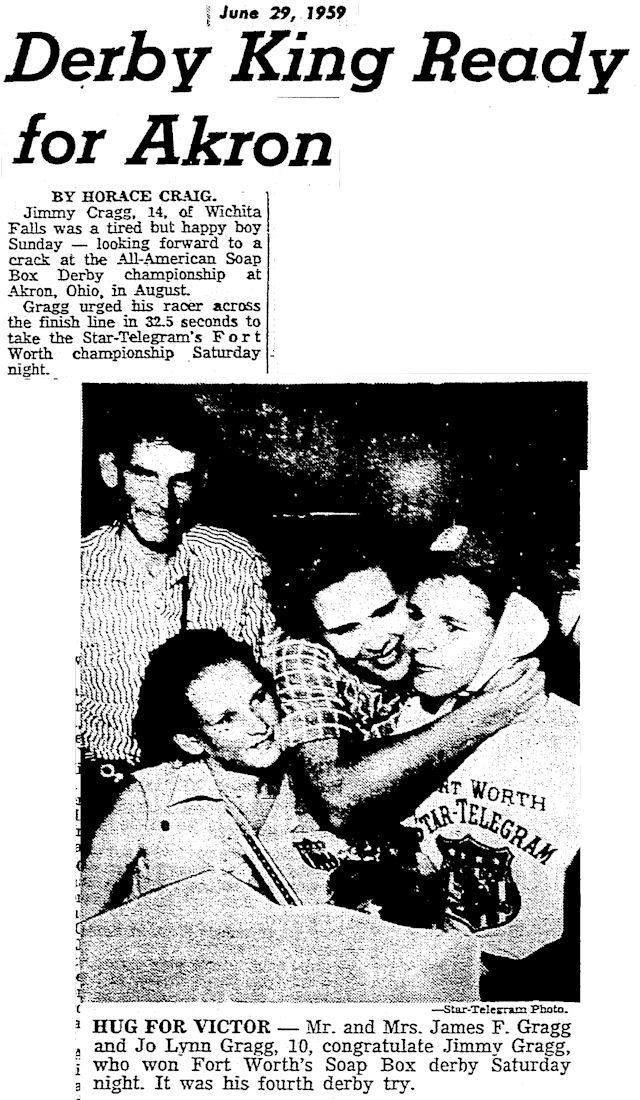

In 1959 Jimmy Gragg, fourteen, of Wichita Falls won the derby on his fourth try with a time of 32.5 seconds. He advanced to the national soap box derby in Akron, Ohio.

In 1959 Jimmy Gragg, fourteen, of Wichita Falls won the derby on his fourth try with a time of 32.5 seconds. He advanced to the national soap box derby in Akron, Ohio.

The Fort Worth derby moved to Rolling Downs at Longhorn Park in 1971. The track, 975 feet long and 30 feet wide, was modeled after the national track in Akron. The Fort Worth derby was sponsored by the Star-Telegram.

The Fort Worth derby moved to Rolling Downs at Longhorn Park in 1971. The track, 975 feet long and 30 feet wide, was modeled after the national track in Akron. The Fort Worth derby was sponsored by the Star-Telegram.

Also in 1971 the derby began admitting girls.

The derby was held annually until about 1985 and resumed briefly in 1991, when Betsy Wells of Crowley, age eleven, won.

At Rolling Downs you can still see the straight racetrack (top) and the footprint of the return path that led from the finish line of the racetrack on the right back to the storage building and parking lot on the left.

At Rolling Downs you can still see the straight racetrack (top) and the footprint of the return path that led from the finish line of the racetrack on the right back to the storage building and parking lot on the left.

And the track’s storage building still stands.

And the track’s storage building still stands.

Watch silent home movie footage of the 1957 derby on YouTube.

… Over the summer I was trespassing at Rolling downs, today I am kicking bones at the former Green valley race city, apparently history is all around if you know where to find it, or how to navigate your website…

… Absolutely love your work…

Thanks, Scott. No one was more surprised than I to learn that Fort Worth history is all around if we know where to look.