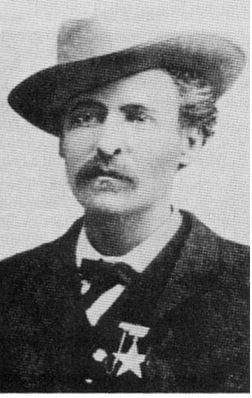

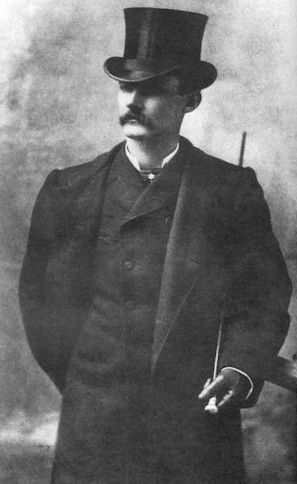

Where did former City Marshal Jim Courtright, wanted for murder in New Mexico, go after his daring escape (see Part 1) from three lawmen in Fort Worth in October 1884? (Photo from Tarrant County College Northeast.)

Where did former City Marshal Jim Courtright, wanted for murder in New Mexico, go after his daring escape (see Part 1) from three lawmen in Fort Worth in October 1884? (Photo from Tarrant County College Northeast.)

Judging from press reports of the time, a better question would be “Where didn’t he go?”

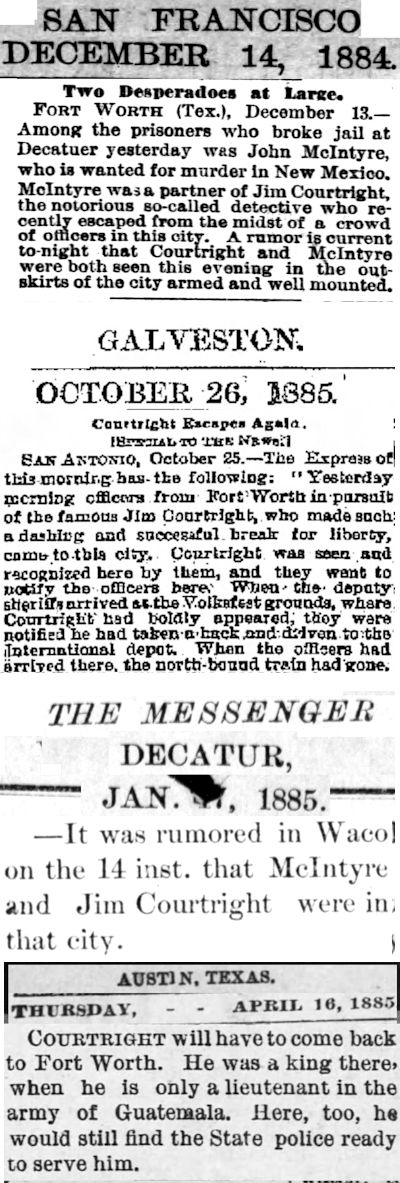

He was reportedly seen in St. Louis, Tucson, Dakota Territory (where he “laid an officer low with a bullet in his brain”), and Caldwell, Kansas (where he was said to have killed a man in an argument).

Courtright also was said to have been seen in Fort Worth, San Antonio, Waco, and Guatemala, where he reportedly was a lieutenant in the army. (The “McIntyre” mentioned in the Decatur brief was Jim McIntire. See Part 1.)

Courtright also was said to have been seen in Fort Worth, San Antonio, Waco, and Guatemala, where he reportedly was a lieutenant in the army. (The “McIntyre” mentioned in the Decatur brief was Jim McIntire. See Part 1.)

In August 1885 Tom Wilson, a friend of Courtright, passed through Dallas. A Dallas Weekly Herald reporter asked Wilson where Courtright was.

In August 1885 Tom Wilson, a friend of Courtright, passed through Dallas. A Dallas Weekly Herald reporter asked Wilson where Courtright was.

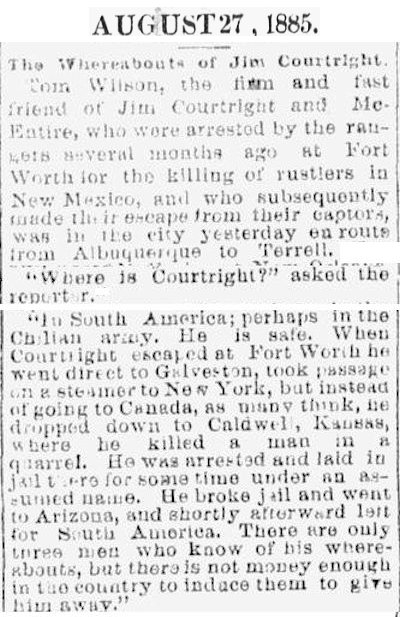

Wilson said that Courtright after his escape had gone first to Galveston, then New York, then Kansas, Arizona, and South America, where he was “perhaps in the Chilian army. He is safe.”

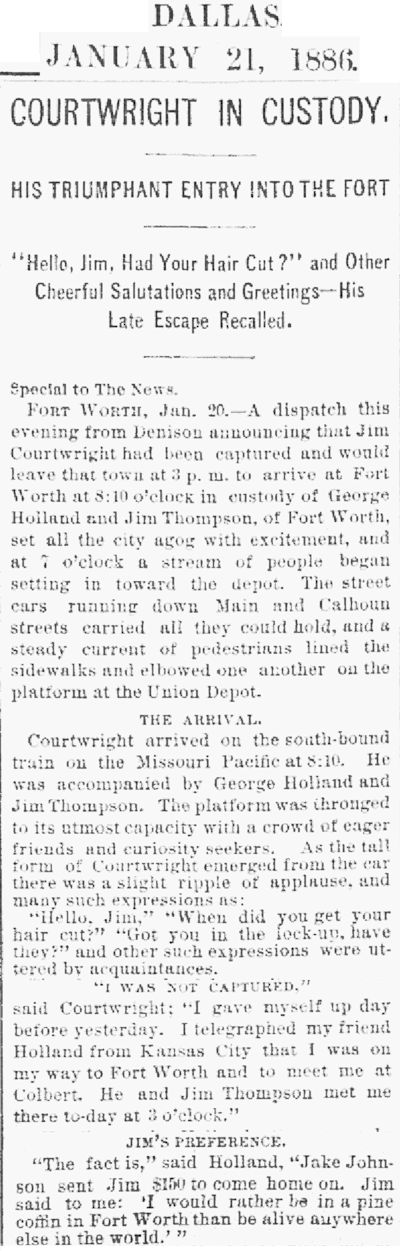

On January 20, 1886, after fifteen months a fugitive, Courtright returned to Fort Worth to surrender to authorities. On the last leg of his return trip he was accompanied by a deputy sheriff and friend George Holland, owner of a Fort Worth variety theater.

On January 20, 1886, after fifteen months a fugitive, Courtright returned to Fort Worth to surrender to authorities. On the last leg of his return trip he was accompanied by a deputy sheriff and friend George Holland, owner of a Fort Worth variety theater.

The Dallas Morning News wrote that Courtright’s “triumphant entry into the fort” “set all the city agog with excitement.”

Of Courtright’s escape in 1884 the Morning News wrote that after he had fled the three lawmen at Merchants’ Restaurant, friend Abe Woody snuck Courtright onto a Santa Fe baggage car. Courtright went to Galveston, boarded a steamer for New York City, thence traveled to Toronto, Chicago, Iowa, Dakota Territory, and finally Washington Territory, where he worked as a blacksmith.

Holland said, “Jake Johnson sent Jim $150 to come home on. Jim said to me, ‘I would rather be in a pine coffin in Fort Worth than be alive anywhere else in the world.’”

Be careful what you wish for, Marshal Jim.

Note that one person asked Courtright, “When did you get your hair cut?” Biographer Robert DeArment says that is perhaps the only contemporary suggestion that “Longhair Jim” Courtright’s hair was long.

Courtright was not jailed in Fort Worth while he awaited trial in New Mexico.

So, he was still a free man two months later when Fort Worth experienced its first major labor-management conflict.

In March 1886 members of the Knights of Labor union went on strike, severely limiting rail transportation in much of the Southwest. The strike began with Texas & Pacific workers in Texas and spread to other railroads (including Missouri Pacific), other unions, other states. Thousands of workers struck in Texas, Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas, and Illinois.

In Fort Worth, a railroad hub, on March 25 the Fort Worth Gazette reported that the few trains that were running were moving slowly in case the tracks had been vandalized by strikers. And indeed strikers and sympathizers tampered with track switches, removed coupling gear so rail cars could not be connected.

Lawmen rode on trains to prevent interference from strikers. Armed men—both strikers and lawmen—roamed the train yards.

On April 3 the New York Times described a tense confrontation in Fort Worth’s Missouri Pacific yard. The Times reported that deputy sheriff James Maddox (one of Jim Courtright’s T.I.C. detectives and the brother of Sheriff Walter Maddox) confronted strikers attempting to block a Missouri Pacific train.

On April 3 the New York Times described a tense confrontation in Fort Worth’s Missouri Pacific yard. The Times reported that deputy sheriff James Maddox (one of Jim Courtright’s T.I.C. detectives and the brother of Sheriff Walter Maddox) confronted strikers attempting to block a Missouri Pacific train.

“Kill the engine! Kill the engine!” one striker shouted as the mob closed in on the locomotive.

(To “kill” an engine was a favorite tactic of strikers. To “kill” meant to extinguish the fire under the boiler and to empty the boiler of water and steam, forcing railroad workers to spend up to six hours refilling and reheating the boiler for use.)

“I’ll kill the first man who touches this engine,” deputy Maddox warned the mob. Note that even though Jim Courtright was still facing a murder charge in New Mexico, he received yet another appointment in local law enforcement: Sheriff Maddox had made him a special deputy to help keep the trains running.

On April 3 Missouri Pacific officials decided to try to break the strikers’ blockade. A train left Fort Worth and went north to Hodge Junction (north of today’s Mount Olivet Cemetery), where it picked up some coal cars. The train then headed back south through Fort Worth to deliver the coal to Alvarado.

Riding shotgun in the engine and caboose of that strikebreaker express were Jim Courtright, seven other special deputies, and five railroad guards.

Courtright rode in the cab of the engine with engineer Ed Smith.

The train was not molested going north to Hodge Junction or traveling back south through Fort Worth.

The track switches in town had been “spiked” to prevent strikers from tampering with them.

Then, as the train was two miles south of Union Depot, approaching a railroad switch called “Buttermilk Junction,” engineer Smith saw two groups of men near the tracks, watching the train. Smith also saw that this switch had been tampered with. He would have to stop the train.

As the train stopped, Courtright jumped down, approached the group of men nearer the switch, who were unarmed, and placed the four of them under arrest for tampering with the switch. Then Courtright approached the second group, which was five in number and was armed. With Winchester rifles. Courtright told the men to put down their weapons. He had not yet drawn his pistol. The gunmen, instead of putting down their weapons, dropped to their knees and raised their rifles.

Courtright, the Gazette reported, shouted at the gunmen: “For God’s sake, don’t shoot.”

They shot.

The gunmen then split into two groups and took cover—one behind a pile of railroad ties, the other in tall grass—and began to crossfire at the lawmen as Courtright and his men also took cover. The lawmen had only pistols, which could not match the range of the ambushers’ rifles.

At least one hundred shots were fired during twelve to fifteen minutes. Deputy Richard Townsend was shot in the back. Fort Worth police officer Charles Sneed was shot in the head, and Fort Worth police officer John J. Fulford was shot in the legs and abdomen, but both Sneed and Fulford continued to return fire. Two ambushers were wounded before the ambushers fled into a nearby thicket.

Sneed and Fulford recovered; Townsend died.

One of the lawmen later said the ambushers seemed “particularly anxious to wing Courtright.”

Courtright, witnesses said, spent most of those twelve to fifteen minutes flattened between the rails of the track, keeping his head down. Nonetheless, Courtright later said his hat had two bullet holes in it.

After the smoke cleared at Buttermilk Junction, tensions in Fort Worth ran even higher. Mayor John Peter Smith asked the governor to send Texas Rangers to help keep the peace. Among the Rangers dispatched was Captain Sam McMurray, who had tried to arrest Courtright in 1884.

After the smoke cleared at Buttermilk Junction, tensions in Fort Worth ran even higher. Mayor John Peter Smith asked the governor to send Texas Rangers to help keep the peace. Among the Rangers dispatched was Captain Sam McMurray, who had tried to arrest Courtright in 1884.

To control what the Dallas Morning News called a “scene of war,” Smith also appointed sixty-nine men to a special police force. Among them was gambler Luke Short.

“The city,” the Morning News wrote, “can be said to be resting over a volcano that is liable to break out at any moment.”

But the peacekeepers managed to keep the peace in the following few days, and calm soon returned.

Calm may have returned, but the public and the Texas press were critical of Sheriff Maddox for appointing Courtright as a special deputy and critical of Courtright for letting himself and his men be ambushed and for hugging the ground between the rails as bullets whizzed overhead during what became known as the “Battle of Buttermilk Junction.”

Calm may have returned, but the public and the Texas press were critical of Sheriff Maddox for appointing Courtright as a special deputy and critical of Courtright for letting himself and his men be ambushed and for hugging the ground between the rails as bullets whizzed overhead during what became known as the “Battle of Buttermilk Junction.”

Courtright’s reputation was tarnished. On top of that he still faced a murder charge in New Mexico.

In November Courtright finally returned to New Mexico to stand trial for the May 1883 murders of homesteaders Grossetete and Elsinger. But prosecutors admitted that they could not produce witnesses and asked that the murder charges be dropped.

When Jim Courtright walked out from under the legal cloud that had hung over him for three and a half years, he had only two months to live.

Courtright returned to Fort Worth to devote his full attention to his detective agency.

Courtright returned to Fort Worth to devote his full attention to his detective agency.

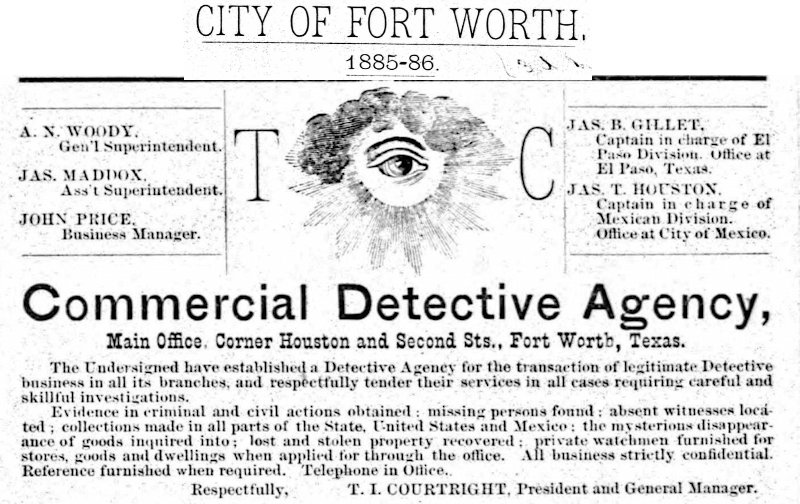

This ad for Courtright’s T.I.C. Commercial Detective Agency appeared in the 1885 city directory: “Evidence in criminal and civil actions obtained: missing persons found: absent witnesses located: collections made in all parts of the State, United States and Mexico: the mysterious disappearance of goods inquired into: lost and stolen property recovered: private watchmen furnished for stores, goods and dwellings when applied for through the office.”

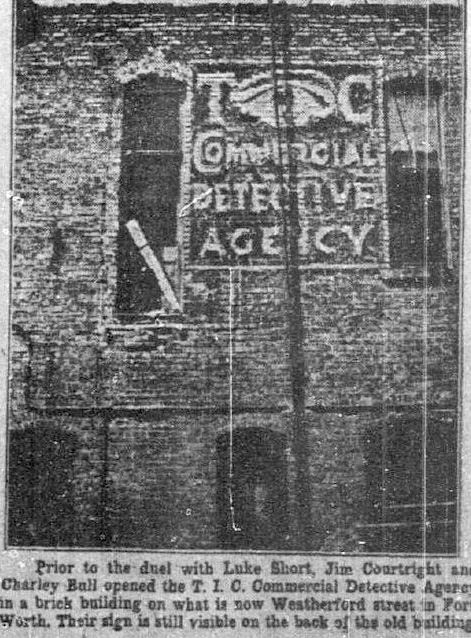

This Dallas Morning News photo of 1929 shows a ghost sign: A wall advertisement for Courtright’s detective agency survived well into the twentieth century.

This Dallas Morning News photo of 1929 shows a ghost sign: A wall advertisement for Courtright’s detective agency survived well into the twentieth century.

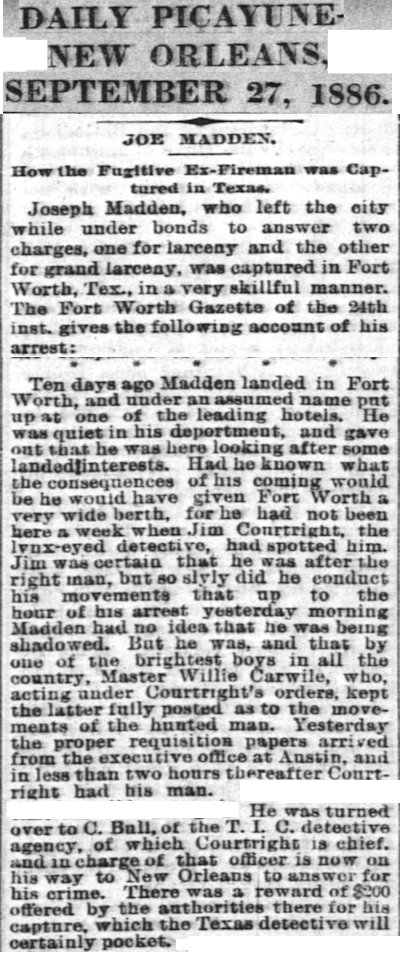

In September the New Orleans Daily Picayune described the “very skillful manner” in which fugitive Joe Madden was captured by “Jim Courtright, the lynx-eyed detective.” The report said Courtright would pocket a reward of $200 ($5,800 today).

In September the New Orleans Daily Picayune described the “very skillful manner” in which fugitive Joe Madden was captured by “Jim Courtright, the lynx-eyed detective.” The report said Courtright would pocket a reward of $200 ($5,800 today).

And it seems that Courtright had a supplemental revenue stream: He collected payoffs from Fort Worth saloons and gambling halls in what Fort Worth historian Dr. Richard Selcer in Hell’s Half Acre calls a “highly profitable protection racket.”

But then Courtright tried to collect payoffs from Luke Short, who ran the gambling operation at the White Elephant Saloon. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

But then Courtright tried to collect payoffs from Luke Short, who ran the gambling operation at the White Elephant Saloon. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Short refused to pay.

Courtright seethed.

Bat Masterson in 1907 suggested another reason for bad blood between Courtright and Short: “It appears that this fellow Courtright . . . had asked Short to install him as a special officer in the White Elephant.” To which Short replied: “You know that the people about here are all afraid of you, and your presence in my house would ruin my business.”

Courtright, Masterson wrote, got “huffy” and threatened to have Short indicted and his gambling operation closed.

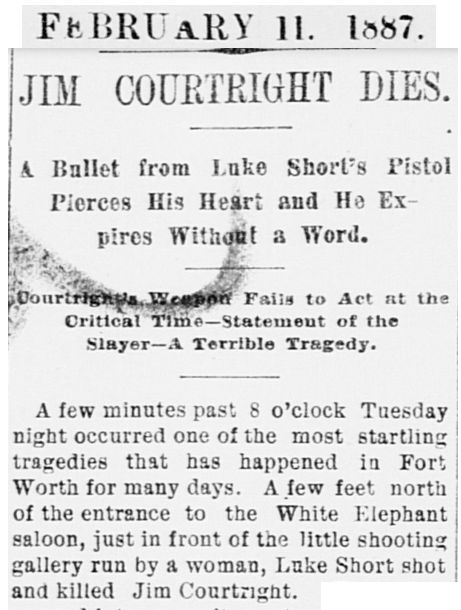

And so it was that on the night of February 8, 1887 Jim Courtright, “huffy” and probably liquored up, went to the White Elephant to confront Short. Gambler Jake Johnson, a friend of both Courtright and Short, intercepted Courtright and told him that he would go in to fetch Short and bring him outside to talk with Courtright. After Johnson accompanied Short out of the saloon, Johnson was the only witness to what happened next.

Short, Courtright, and Johnson walked away from the White Elephant, north along the sidewalk on Main Street. In front of Ella Blackwell’s shooting gallery they stopped, talking as they stood three or four feet apart.

(For the record, the White Elephant Saloon was an “uptown” saloon, located at 308-310 Main Street, just three blocks from the courthouse, not in Hell’s Half Acre and not at the stockyards. The Morris Building today occupies the site of the original saloon on Main Street.)

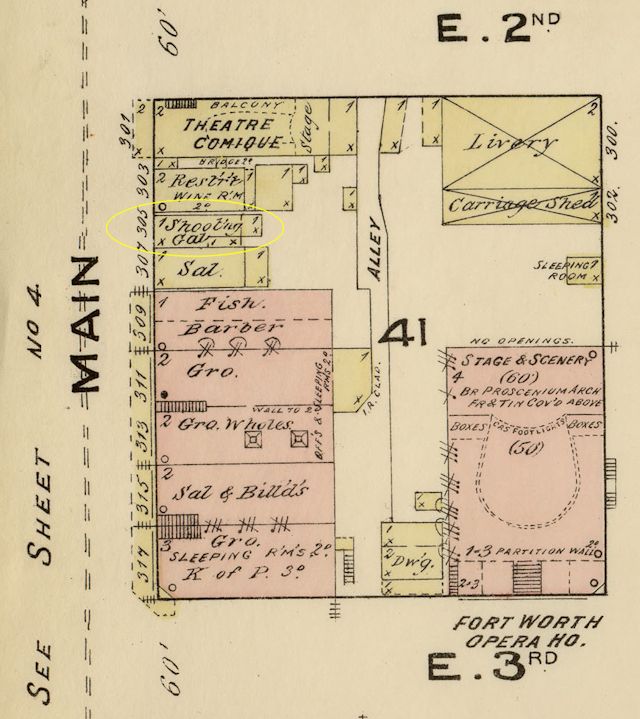

An 1885 map shows an unnamed shooting gallery at 305 Main across the street from the White Elephant.

An 1885 map shows an unnamed shooting gallery at 305 Main across the street from the White Elephant.

The Gazette later quoted Johnson as he testified about what he had witnessed as Short and Courtright talked on the sidewalk: “Luke had his thumbs in the armholes of his vest, then he dropped them in front of him when Courtright said, ‘You needn’t be getting out your gun.’ Luke said, ‘I haven’t got any gun here, Jim’ and raised up his vest to show him. Courtright then pulled his pistol. He drew it first, and then Short drew his and commenced to fire.”

Jim Courtright, the famed gunslinger, never fired a shot. Some historians theorize that Courtright’s gun jammed or that the hammer of his pistol snagged his watch chain. Otherwise, those historians ponder, how could anyone, even Luke Short, have outdrawn the gunslinger known for his fast draw? Courtright, the Gazette said, was deadly accurate with either hand and “as quick as lightning.” “In a desperate emergency his coolness and self-possession never left him.”

And yet there he was—dead on the floor of a shooting gallery. Short’s first shot had been fired at close range. Courtright fell into the entrance of the shooting gallery, his boots on the sidewalk, his .45 still in his hand. Short fired four more times. Police officer Fulford recovered from his Buttermilk Junction wounds, quickly arrived at the scene. He bent over Courtright. Fulford later testified that Courtright’s last words were “Ful, they’ve got me.”

Also quick to arrive at the scene was police officer William Bonaparte (“Bony”) Tucker Jr. (Tucker had fought alongside Courtright and Fulford at the Battle of Buttermilk Junction.) Officer Tucker had been standing at the corner of 3rd and Main streets when a man rushed up and warned Tucker that “there was going to be trouble between Jim Courtright and Luke Short.” Soon after, Tucker said, “the crack of a pistol rang out.” As Tucker ran north he heard four more shots. By the time he reached the shooting gallery, Courtright was too weak to speak.

Tucker told the Gazette that Courtright “grasped his gun in one hand, a ‘45’ of the same make as the one that killed him. The chambers were full of cartridges, showing that he had failed to get in a shot. Three bullets had taken effect. One broke his right thumb, the second passed through his heart and the third struck him in the right shoulder. . . . He was a dead man within five minutes after I reached him.”

The testimony of Fulford notwithstanding, the Gazette said Courtright died without uttering a word.

The testimony of Fulford notwithstanding, the Gazette said Courtright died without uttering a word.

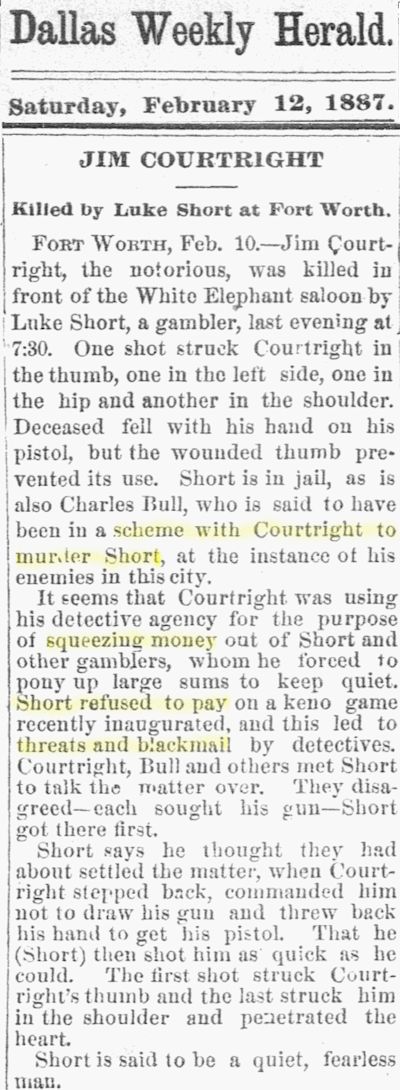

The Dallas Weekly Herald addressed the reason for bad blood between the two men: “It seems that Courtright was using his detective agency for the purpose of squeezing money out of Short and other gamblers, whom he forced to pay up large sums to keep quiet. Short refused to pay on a keno game recently inaugurated, and this led to threats and blackmail by [T.I.C.] detectives.”

The Dallas Weekly Herald addressed the reason for bad blood between the two men: “It seems that Courtright was using his detective agency for the purpose of squeezing money out of Short and other gamblers, whom he forced to pay up large sums to keep quiet. Short refused to pay on a keno game recently inaugurated, and this led to threats and blackmail by [T.I.C.] detectives.”

Note that the Herald says that T.I.C. detective Charles Bull “is said to have been in a scheme with Courtright to murder Short, at the instance of his enemies in this city.”

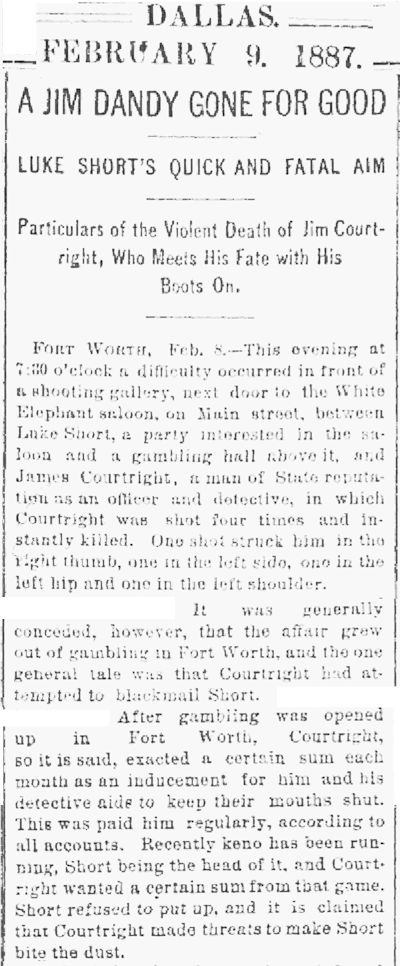

Likewise, the Dallas Morning News repeated the shakedown angle and even worked in the phrase “bite the dust”:

Likewise, the Dallas Morning News repeated the shakedown angle and even worked in the phrase “bite the dust”:

“Courtright had attempted to blackmail Short. . . . After gambling was opened up in Fort Worth, Courtright, so it is said, exacted a certain sum each month as an inducement for him and his detective aides to keep their mouths shut. This was paid him regularly, according to all accounts. Recently keno has been running, Short being the head of it, and Courtright wanted a certain sum from that game. Short refused to put up, and it is claimed that Courtright made threats to make Short bite the dust.”

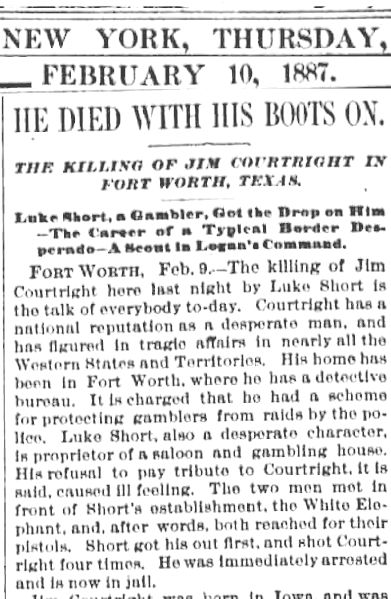

The “shootout” made headlines around the country, including page 1 of the New York Sun. This report, too, alludes to Courtright’s protection racket: “It is charged that he had a scheme for protecting gamblers from raids by the police.” Short’s “refusal to pay tribute to Courtright, it is said, caused ill feeling.”

The “shootout” made headlines around the country, including page 1 of the New York Sun. This report, too, alludes to Courtright’s protection racket: “It is charged that he had a scheme for protecting gamblers from raids by the police.” Short’s “refusal to pay tribute to Courtright, it is said, caused ill feeling.”

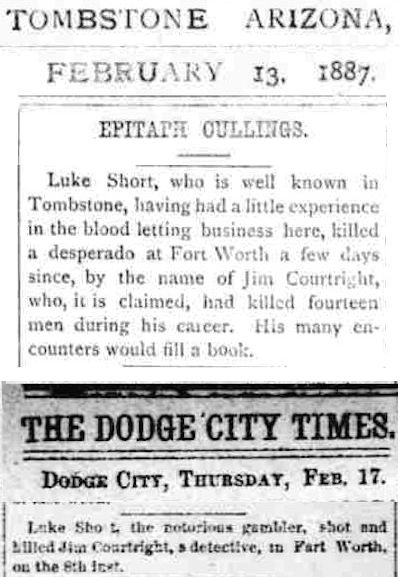

The “shootout” made headlines in two other towns where Luke Short had lived: Tombstone and Dodge City.

The “shootout” made headlines in two other towns where Luke Short had lived: Tombstone and Dodge City.

Courtright biographer Father Stanley Crocchiola’s account of the relationship between Courtright and Short is at odds with that of most other historians. Crocchiola claims that Courtright owned the White Elephant Saloon and rented the upstairs gambling room to Luke Short. When city fathers complained to Courtright about Short’s gambling operation, Courtright threatened to shut it down. But wait! There’s more. Crocchiola writes that Luke Short was in love with Betty Courtright and wanted to lure her husband into a situation where someone—possibly Bat Masterson or Wyatt Earp—could kill Courtright in self-defense.

As it turned out, Courtright prodded Luke Short into doing the work himself.

After the smoke had cleared for the last time in the life of Timothy Isaiah Courtright, William Capps, who had been Courtright’s attorney in 1884, was one of Luke Short’s attorneys. Another Short attorney was Robert McCart.

The coroner’s jury ruled only that Courtright had died at the hands of Luke Short.

At the examining trial one witness, W. A. James, testified that on the night before the shooting he had heard Courtright say “that there was a combination against him over the White Elephant,” “that he hadn’t been treated with respect upstairs over the White Elephant.”

The saloon’s gambling room was upstairs over the bar.

James testified that Courtright said, “God had made one man superior to another in muscular power, but when Colt made his pistol, that made all men equal.” James again quoted Courtright: “Courtright said he had lived over his time. No man on earth, he said, had a percentage over him. He said that this would be settled within a week.”

As for Luke Short, he was no-billed by a grand jury. He had acted in self-defense. In those days, when one armed man killed another armed man, a charge of murder was rare unless the victim was shot in the back.

And as the killings of Grossetete and Elsinger show, sometimes not even then: DeArment writes that none of the six killers was ever convicted.

Marshall Jim’s funeral was held at his home, as was the custom of the day.

Marshall Jim’s funeral was held at his home, as was the custom of the day.

At the head of the funeral procession was a fire wagon of the M. T. Johnson fire brigade of which Courtright had been a member. The wagon, draped in mourning, was drawn by two horses, one of them named “Jim” after Courtright.

The procession of carriages was six blocks long.

Courtright was buried with Odd Fellows rites at Oakwood Cemetery.

And so it was that there on that green hillside across the river where farmer Jim had walked behind a plow fourteen years earlier, the man who has been called Fort Worth’s “first citizen” and “first gangster” was planted, and a western legend sprouted.

And so it was that there on that green hillside across the river where farmer Jim had walked behind a plow fourteen years earlier, the man who has been called Fort Worth’s “first citizen” and “first gangster” was planted, and a western legend sprouted.

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade