It is a story of two men who led very different lives but were immortalized by the same word. One man came from the hills of Arkansas, the other from the mountains of Switzerland. One man invented an instrument that helped Americans forget about a war, the other man invented an instrument that helped Americans win a war.

Bob Burns was born in Greenwood, Arkansas in 1890. His family soon moved to Van Buren, Arkansas, where he began taking trombone and mandolin lessons at age six.

Burns later recalled: “When I was nine I was playing the slide trombone with Frank MacClain’s Van Buren Queen City Silvertone Comet Band.”

At age thirteen Burns formed his own band: “In 1905 our string band was practicing in back of Hayman’s Plumbing Shop in Van Buren, and while we were playing ‘Over the Waves’ waltz, I broke a string on the mandolin. With nothing else to do, I picked up a piece of gas pipe, inch and a half in diameter and about twenty inches long. And when I blew in one end, I was very much surprised to get a bass note. Then, kidlike, I rolled up a piece of music and stuck it in the other end of the gas pipe and found that sliding it out and in like a trombone, I could get about three ‘fuzzy’ bass notes. The laughter that I got encouraged me to have a tin tube made that I could hold on to and slide back and forth inside the inch-and-a-half gas pipe. Later on I soldered a funnel on the end of the tin tube, and a wire attached to the funnel to give me a little longer reach.”

At age thirteen Burns formed his own band: “In 1905 our string band was practicing in back of Hayman’s Plumbing Shop in Van Buren, and while we were playing ‘Over the Waves’ waltz, I broke a string on the mandolin. With nothing else to do, I picked up a piece of gas pipe, inch and a half in diameter and about twenty inches long. And when I blew in one end, I was very much surprised to get a bass note. Then, kidlike, I rolled up a piece of music and stuck it in the other end of the gas pipe and found that sliding it out and in like a trombone, I could get about three ‘fuzzy’ bass notes. The laughter that I got encouraged me to have a tin tube made that I could hold on to and slide back and forth inside the inch-and-a-half gas pipe. Later on I soldered a funnel on the end of the tin tube, and a wire attached to the funnel to give me a little longer reach.”

And the bazooka was born.

Burns said: “No doubt you have heard the expression, ‘He blows his bazoo too much.’ In Arkansas that is said of a ‘windy guy’ who talks too much. Inasmuch as the bazooka is played by the mouth, it’s noisy and takes a lot of wind. It just seemed like ‘bazoo’ fitted in pretty well as part of the name. The affix ‘ka’ rounded it out and made it sound like the name of a musical instrument—like balalaika and harmonica.”

Burns began to entertain audiences with his bazooka and his comedy, spinning yarns about his “hillbilly” relatives.

The year 1935 was pivotal for Burns. In New York City he auditioned for bandleader Paul Whiteman. Soon after, Burns appeared on Whiteman’s coast-to-coast radio program—broadcast locally on WBAP—and became a national sensation. Soon he was also appearing as a regular guest on Rudy Vallee’s radio program.

The year 1935 was pivotal for Burns. In New York City he auditioned for bandleader Paul Whiteman. Soon after, Burns appeared on Whiteman’s coast-to-coast radio program—broadcast locally on WBAP—and became a national sensation. Soon he was also appearing as a regular guest on Rudy Vallee’s radio program.

Burns was known as the “Arkansas Traveler.”

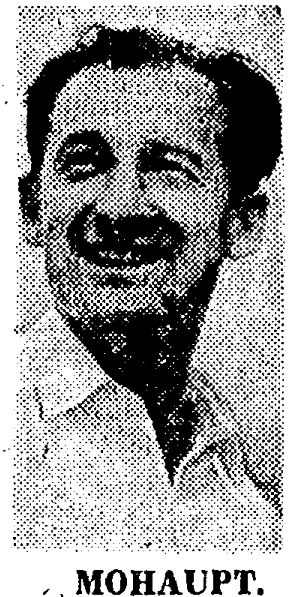

The year 1935 also was pivotal for Henry Mohaupt. Born “Wolfdieter Hans-Jochem Mohaupt” in Switzerland in 1915, Mohaupt, only twenty years old, combined his education (chemical engineering) and his hobby (firearms) to develop a shaped-charged munition: an explosive charge shaped to focus the effect of the explosive’s energy.

The year 1935 also was pivotal for Henry Mohaupt. Born “Wolfdieter Hans-Jochem Mohaupt” in Switzerland in 1915, Mohaupt, only twenty years old, combined his education (chemical engineering) and his hobby (firearms) to develop a shaped-charged munition: an explosive charge shaped to focus the effect of the explosive’s energy.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “The principle of the shaped charge dates back to 1880 when the phenomenon known as the ‘cavity effect of explosives’ was discovered by Dr. Charles E. Munroe. The principle remained with no practical application until in the 1930s when Mohaupt became interested in it and perfected some variations. Chief of these was the insertion of a liner behind the explosive to give it additional force and direction.”

The Star-Telegram wrote that Mohaupt was working on the principle of the shaped-charge projectile—a small rocket—for the French navy at the outbreak of World War II. The fall of France prevented completion of the project, and Mohaupt fled to the United States to develop his rocket for use by the Allies.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “From the time he arrived in the United States in July 1940 until after the close of the war, he was guarded like the Fort Knox gold reserve.”

Mohaupt’s rocket was demonstrated at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in December 1940.

Mohaupt’s rocket was demonstrated at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in December 1940.

The book The Ordnance Department: Planning Munitions for War (1955) compiled by the federal government’s Office of the Chief of Military History says, “The demonstration at Aberdeen convinced the Army and Navy men who witnessed it that here indeed was an important ‘new form of munition.’ They at once recommended purchasing rights to employ the Mohaupt principle in any form to which it might prove adaptable.”

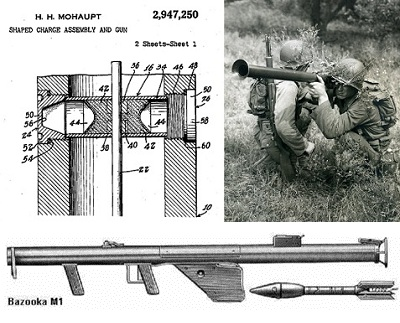

The Army developed a hand-held metal tube to launch Mohaupt’s rocket. The launcher and its rocket were, literally, a secret weapon. They were classified as top secret, initially known by the code name “the Whip.”

On the day that propelled America into World War II, the word bazooka still meant just one thing: Bob Burns’s homemade trombone.

On the day that propelled America into World War II, the word bazooka still meant just one thing: Bob Burns’s homemade trombone.

As America went to war and as Americans went overseas to fight that war, Bob Burns continued to play his bazooka and, like other entertainers, to help Americans forget, if only during a radio program or a phonograph record or a movie, about the war.

As America went to war and as Americans went overseas to fight that war, Bob Burns continued to play his bazooka and, like other entertainers, to help Americans forget, if only during a radio program or a phonograph record or a movie, about the war.

Burns remained a nationwide radio favorite on the Kraft Music Hall and other programs. He drawled tall tales about such mythical relatives as Uncle Fudd, Grandpa Snazzy, Aunt Boo, Uncle Fotchey, and Uncle Slug.

He told audiences that to reach the neck of the woods he came from, travelers had to swing in on the trees the last mile or so.

Burns was proud of his “hillbilly” heritage. He said of country folks: “They’re good, honest people. I ain’t ashamed of them. . . . City folks are the same everywhere. They ain’t different enough to be interesting.”

He once said of Hollywood: “Some folks out here get inflated ideas. But they usually have to come down to earth. I know I’m the same fellow I was years ago when I was glad to make $25 a week. I haven’t got any smarter.”

Burns also wrote a syndicated newspaper column, appeared in twenty-six movies between 1930 and 1945, had his own radio program. He hosted the Academy Awards program in 1938.

As America ended its first full year of World War II in 1942, the word bazooka continued to mean Bob Burns’s homemade trombone.

As America ended its first full year of World War II in 1942, the word bazooka continued to mean Bob Burns’s homemade trombone.

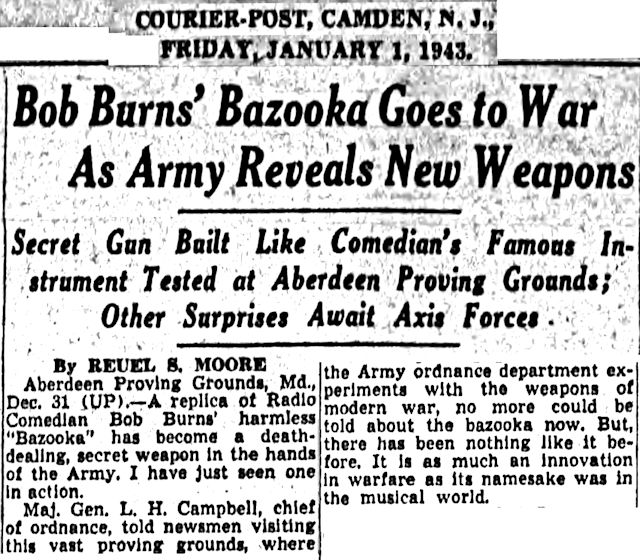

But the new year brought a new meaning of the word.

But the new year brought a new meaning of the word.

Burns received a letter from the Army’s Ordnance Department telling him that when Henry Mohaupt’s rocket and launcher were demonstrated to a group of officers a General Somervell gave the weapon a surprised look and said, “That damn thing looks just like the Bob Burns’ bazooka.”

The name stuck.

Burns said that was the proudest moment of his life.

Mohaupt’s bazooka was introduced on the Russian front in November 1942 and later used in north Africa. The bazooka was a wonder weapon. Its shaped-charge projectile was as powerful as much larger projectiles and was effective at a slower velocity. Just as important, the weapon was recoilless and compact enough to be operated by an infantryman. For the first time a soldier could carry a weapon that could penetrate the armor of tanks, including the 50-millimeter armor plate of the German Panzerkampfwagen III tank.

Mohaupt’s bazooka was introduced on the Russian front in November 1942 and later used in north Africa. The bazooka was a wonder weapon. Its shaped-charge projectile was as powerful as much larger projectiles and was effective at a slower velocity. Just as important, the weapon was recoilless and compact enough to be operated by an infantryman. For the first time a soldier could carry a weapon that could penetrate the armor of tanks, including the 50-millimeter armor plate of the German Panzerkampfwagen III tank.

America and its allies used the bazooka—a weapon invented by a man from a country with a long tradition of military neutrality—in several ways but most dramatically to disable German tanks. General Dwight Eisenhower later described the bazooka as one of the four “Tools of Victory” (together with the atom bomb, Jeep, and the C-47 Skytrain transport aircraft) that won the war for America and its allies.

America and its allies used the bazooka—a weapon invented by a man from a country with a long tradition of military neutrality—in several ways but most dramatically to disable German tanks. General Dwight Eisenhower later described the bazooka as one of the four “Tools of Victory” (together with the atom bomb, Jeep, and the C-47 Skytrain transport aircraft) that won the war for America and its allies.

(According to The Ordnance Department: Planning Munitions for War, “An adaptation of Mohaupt’s design . . . formed the basis of the bazooka rocket.” However, other scientists, such as Clarence Hickman, Edward G. Uhl, Nevil Hopkins, and Robert Goddard, conducted research similar to that of Mohaupt.)

Fast-forward to 1946, another pivotal year for both Bob Burns and Henry Mohaupt: a change of work, a change of address.

Burns left show business and moved to southern California, where he became a land speculator.

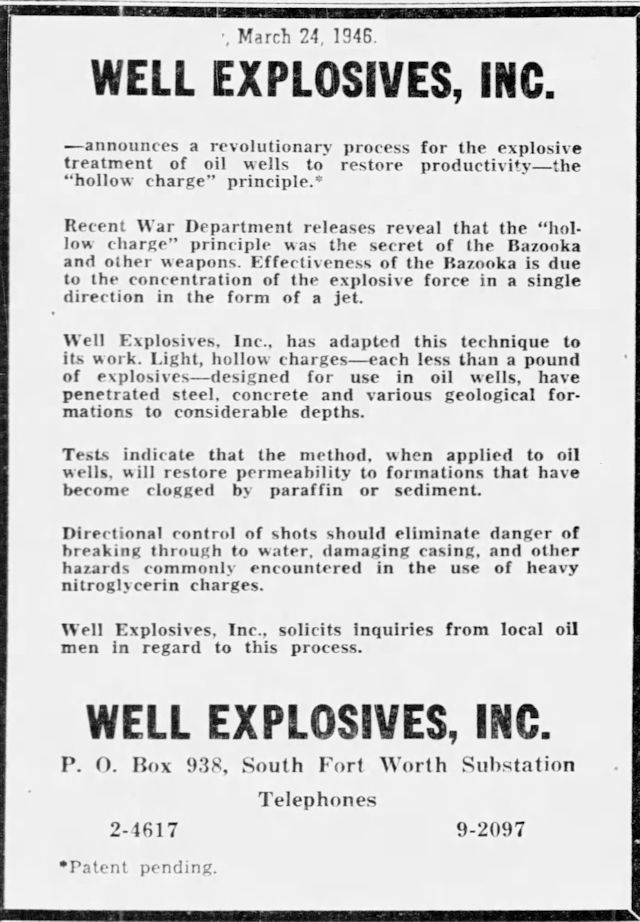

Mohaupt moved to Fort Worth, where he developed an industrial application of his shaped-charge projectile.

Mohaupt moved to Fort Worth, where he developed an industrial application of his shaped-charge projectile.

After the war the Well Explosives (Welex) company of Fort Worth had become interested in the application of the shaped-charge projectile in perforating oil and gas wells. Seeking an expert, the company placed “help wanted” classified ads in large newspapers around the country, including in Washington, D.C., where Mohaupt by then was working with the Navy in the mine warfare countermeasures division. An officer working with Mohaupt was about to return to civilian life and needed a job. He read the Welex ad and notified Welex about Mohaupt. The company brought Mohaupt to Fort Worth about 1947.

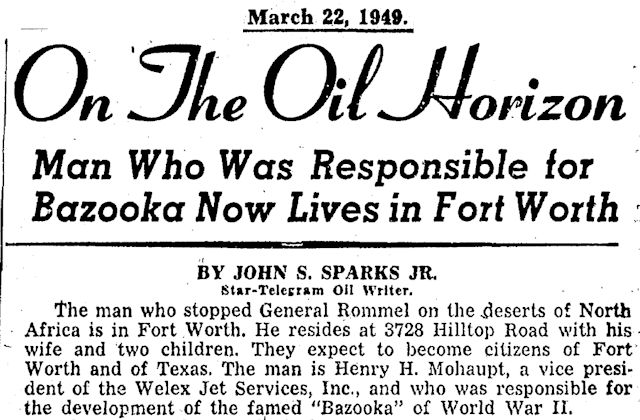

The Star-Telegram interviewed Mohaupt in 1949.

The Star-Telegram interviewed Mohaupt in 1949.

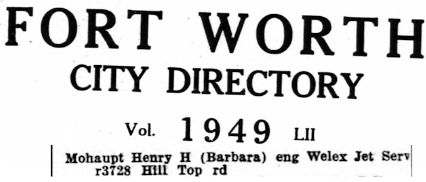

The Mohaupts lived in Westcliff West in this house at 3728 Hilltop Road, built in 1941 but much modified since then.

The Mohaupts lived in Westcliff West in this house at 3728 Hilltop Road, built in 1941 but much modified since then.

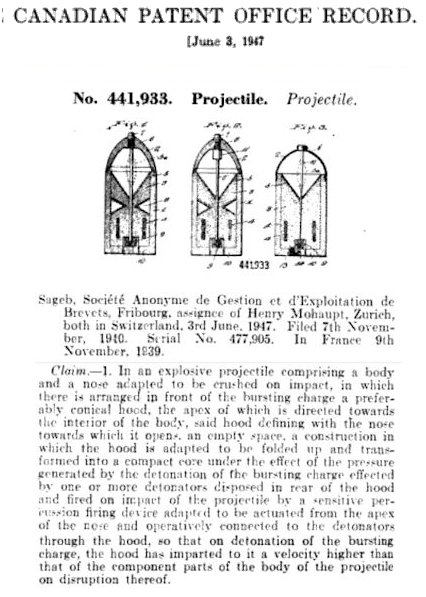

His 1951 patent submission for a “Shaped Charge Assembly and Gun” brought bazooka technology to the petroleum industry.

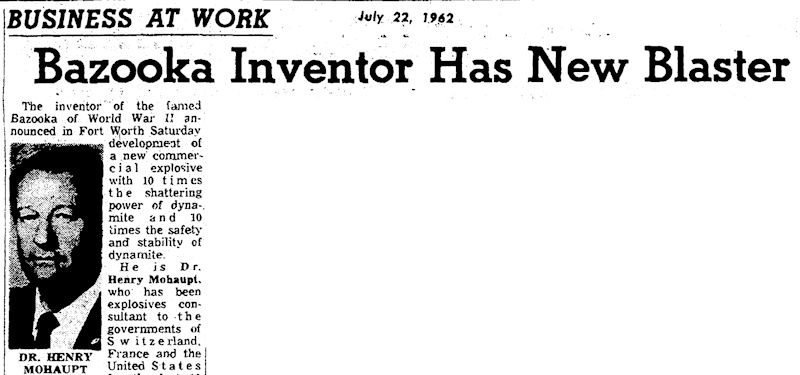

Mohaupt continued his research in industrial explosives. The Star-Telegram wrote: “The inventor of the famed Bazooka of World War II announced in Fort Worth Saturday development of a new commercial explosive with ten times the shattering power of dynamite and thirty times the safety and stability of dynamite.”

Mohaupt continued his research in industrial explosives. The Star-Telegram wrote: “The inventor of the famed Bazooka of World War II announced in Fort Worth Saturday development of a new commercial explosive with ten times the shattering power of dynamite and thirty times the safety and stability of dynamite.”

Mohaupt’s new explosive, the Star-Telegram wrote, “is so stable it can blast a deep cylindrical hole of predictable dimensions without disturbing the load-bearing capacity of surrounding areas. It contains no liquids or volatiles and provides homogenized stability in a high-density solid with no dimensional or chemical variance, a fact that guarantees optimum safety in transport and use.”

By 1962 Mohaupt was president of Fort Worth’s Petroleum Tool Research Company, which manufactured oilfield explosives.

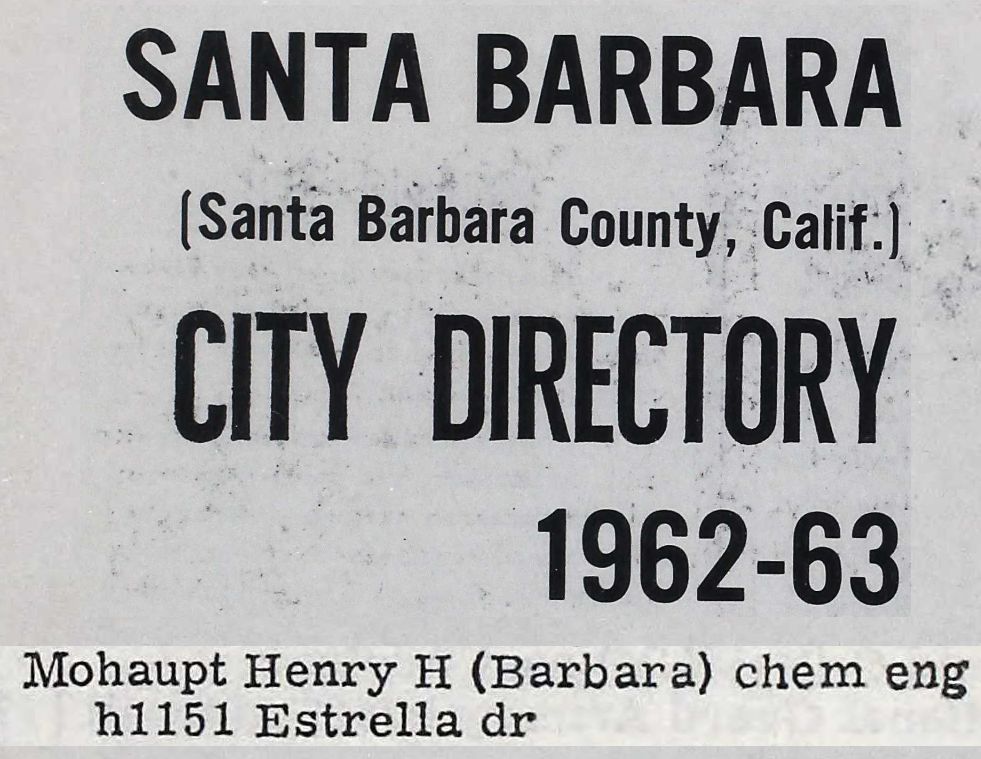

But by 1962 the Mohaupts had moved to California.

But by 1962 the Mohaupts had moved to California.

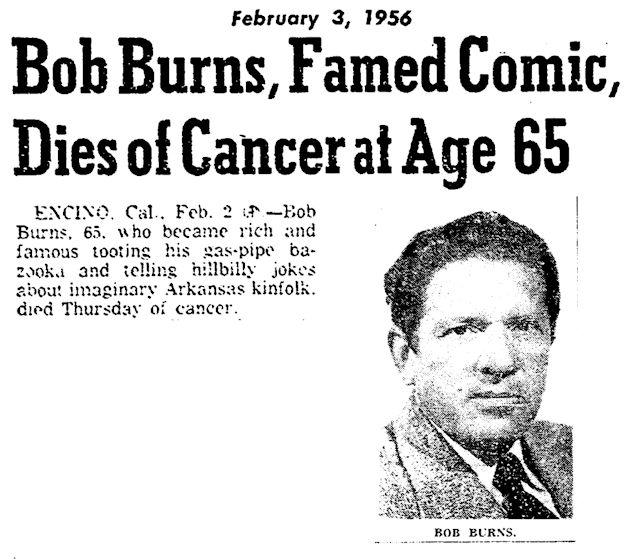

The music man and the rocket man, each of whom invented a bazooka, died seventy-five miles apart in southern California: Burns in Encino in 1956, Mohaupt in Santa Barbara in 2001.

The music man and the rocket man, each of whom invented a bazooka, died seventy-five miles apart in southern California: Burns in Encino in 1956, Mohaupt in Santa Barbara in 2001.

Two videos:

Bob Burns’s bazooka (1936)

Henry Mohaupt’s bazooka (1943)

This is a fascinating account of an entertainer and a scientist. You have an appealing writing style, and you successfully infused the text with pertinent images. As an unofficial “historian” of a major oilfield services company, I appreciate and empathize the effort and time that you expended on this posting. Great job.

Thank you, Noel Atzmiller. What the blog post does not include is the fact that in the mid-1950s my family leased rural land in south Arlington, Texas to Petroleum Tool Research Company. The company built a 20×80-foot explosives factory on the land, and after the company left, I converted the factory into a house and garage and lived there for years. We had no idea, of course, of the connection to the inventor of the bazooka.