While much of the world fought on battle fronts in 1918, much of the world also fought on home fronts.

The enemy at home was an infectious disease: influenza. Where the outbreak of influenza began is still debated—in a British military camp in France, in China, even in Kansas (but not in Spain).

Whatever its origin, when influenza spread to Fort Worth, people contracted the disease and passed it on to others. Hospitals overflowed. Schools closed. Theaters closed. Churches suspended services. People were urged to stay home. Volunteers made face masks as quickly as they could.

Thousands became ill; hundreds died.

In the United States the outbreak of what then was called “Spanish influenza” had been relatively mild in the spring of 1918. The outbreak was more severe on military bases than in cities. Soldiers were being shuttled from camp to camp, where they lived in close quarters. Soldiers frequented the towns near their base. Thus, the military war rendered soldiers the perfect vectors of the enemy in the other “war”: Soldiers spread the disease among themselves and carried it to civilian populations.

In 1918 Fort Worth had a population of about 105,000. But that’s not counting the city’s military population: the National Guard soldiers training at Camp Bowie and the Canadian fliers training at Camp Taliaferro. The Star-Telegram in 1917 had estimated that the two military installations added fifty thousand military and civilian personnel to the local population.

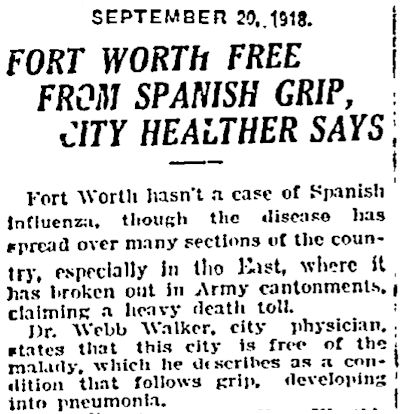

As of September 20 Fort Worth had no cases of influenza.

As of September 20 Fort Worth had no cases of influenza.

But two headlines in the Star-Telegram indicate how quickly the invisible enemy invaded Camp Bowie:

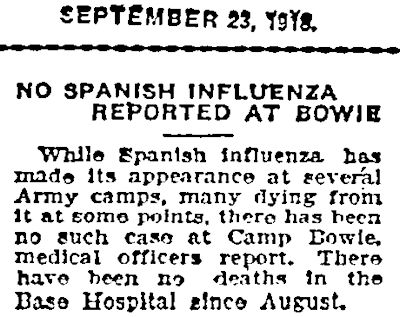

On September 23 the Star-Telegram reported no cases of influenza at Camp Bowie.

On September 23 the Star-Telegram reported no cases of influenza at Camp Bowie.

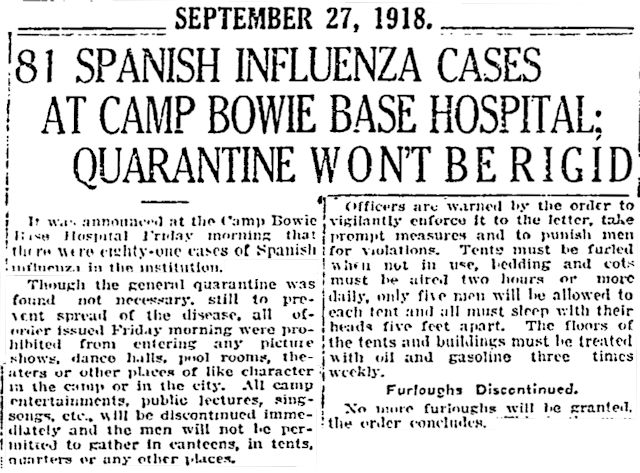

Four days later the Star-Telegram reported eighty-one cases of influenza at the camp.

Four days later the Star-Telegram reported eighty-one cases of influenza at the camp.

Nonetheless, no general quarantine was imposed at Camp Bowie. Soldiers were free to leave the camp, but they were not allowed to enter any place of amusement in the camp or in the city or to congregate in tents or canteens. All camp entertainments were canceled, as were furloughs.

Soldiers were ordered to furl tents when not in use, to air bedding and cots two hours or more daily, to sleep with heads five feet apart, and to disinfect the floors of tents with oil and gasoline three times a week.

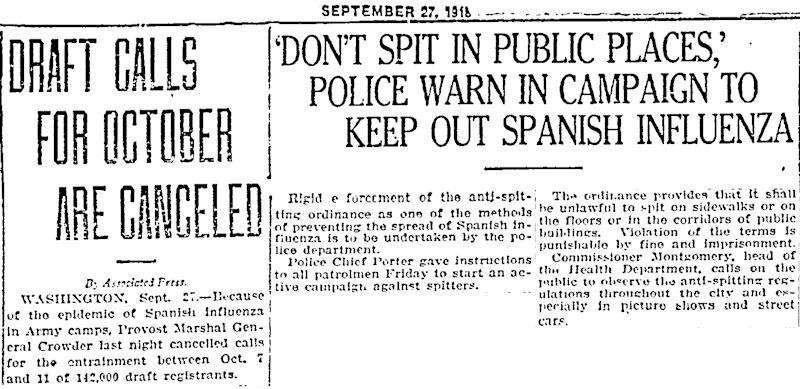

Meanwhile the Army suspended the draft call because of the outbreak.

Meanwhile the Army suspended the draft call because of the outbreak.

And the city began to react, albeit tentatively. It declared that the anti-spitting ordinance would be rigidly enforced, especially in theaters and on streetcars.

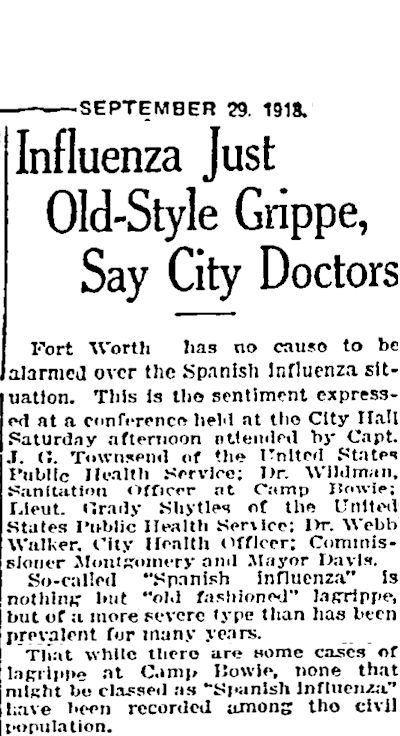

As September ended, the city still had reported no case of influenza among civilians. Physicians, including city health officer Dr. Webb Walker and doctors of the United States Public Health Service and Camp Bowie, said the public had no need for alarm. The disease, they said, was just “old-fashioned” la grippe (influenza), albeit “of a more severe type.”

As September ended, the city still had reported no case of influenza among civilians. Physicians, including city health officer Dr. Webb Walker and doctors of the United States Public Health Service and Camp Bowie, said the public had no need for alarm. The disease, they said, was just “old-fashioned” la grippe (influenza), albeit “of a more severe type.”

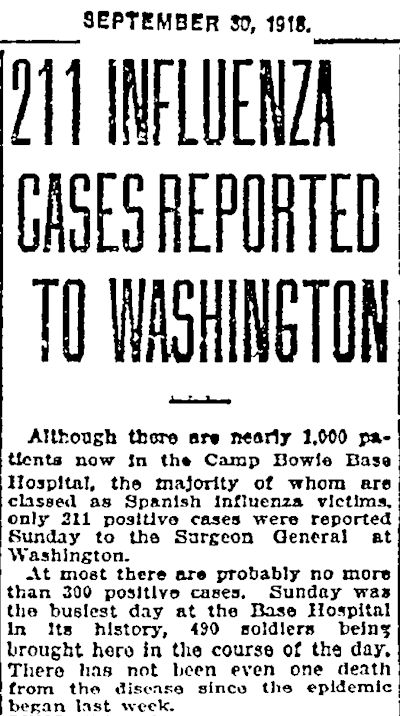

A week after Camp Bowie had reported no cases, it reported 211 cases.

A week after Camp Bowie had reported no cases, it reported 211 cases.

In the base hospital influenza patients were segregated from other patients. Even the chaplain was not allowed into the influenza area.

But the camp had not yet recorded a death from influenza.

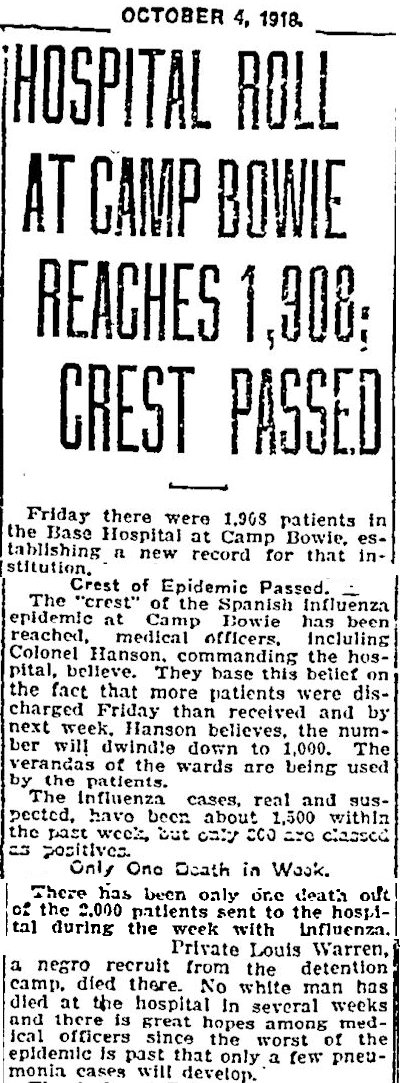

That changed on October 3 when Private Louis Warren died of bacterial pneumonia after contracting influenza. Most deaths of the outbreak resulted from the progression from influenza to pneumonia.

That changed on October 3 when Private Louis Warren died of bacterial pneumonia after contracting influenza. Most deaths of the outbreak resulted from the progression from influenza to pneumonia.

Although two thousand camp personnel had been hospitalized with influenza that week, camp officers hoped that the outbreak had crested because more patients were being discharged than admitted.

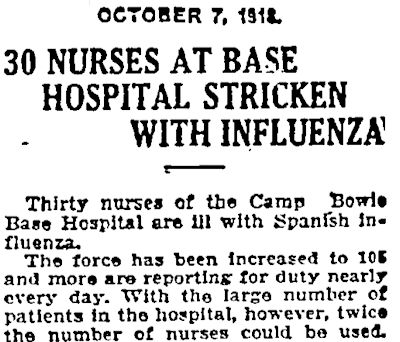

But as the first week of October ended, almost one-third of the nurses at Camp Bowie had influenza.

But as the first week of October ended, almost one-third of the nurses at Camp Bowie had influenza.

(Army nurse Ella Behrens, of German parentage, fell under suspicion of being an enemy agent and spreading influenza germs to camp soldiers. She was briefly jailed and then given a dishonorable discharge because she had been AWOL while in jail. Not until thirty-one years later was her name cleared.)

As the second week of October began, Fort Worth reported two hundred cases of influenza, although Captain J. G. Townsend of the United States Public Health Service said he suspected a number of cases were not reported.

As the second week of October began, Fort Worth reported two hundred cases of influenza, although Captain J. G. Townsend of the United States Public Health Service said he suspected a number of cases were not reported.

One day later the number of cases had increased fivefold. The outbreak was especially severe in a densely populated neighborhood on the North Side that housed Mexican nationals who worked at the packing plants. One physician found sixty-four people living in three rooms, many of them ill with influenza or pneumonia.

One day later the number of cases had increased fivefold. The outbreak was especially severe in a densely populated neighborhood on the North Side that housed Mexican nationals who worked at the packing plants. One physician found sixty-four people living in three rooms, many of them ill with influenza or pneumonia.

They were evacuated to an emergency hospital set up in the old Fort Worth University medical school on Calhoun Street.

Meanwhile the school board resisted closing the schools, arguing that students who were free to roam about town instead of confined to classrooms could spread the disease beyond school buildings.

That argument would be short-lived.

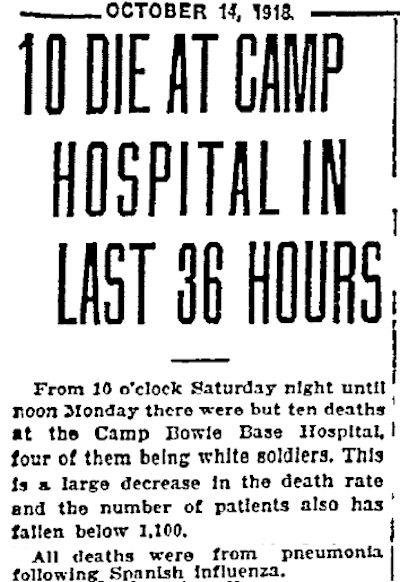

At Camp Bowie ten men died of influenza-induced pneumonia during a thirty-six-hour period.

At Camp Bowie ten men died of influenza-induced pneumonia during a thirty-six-hour period.

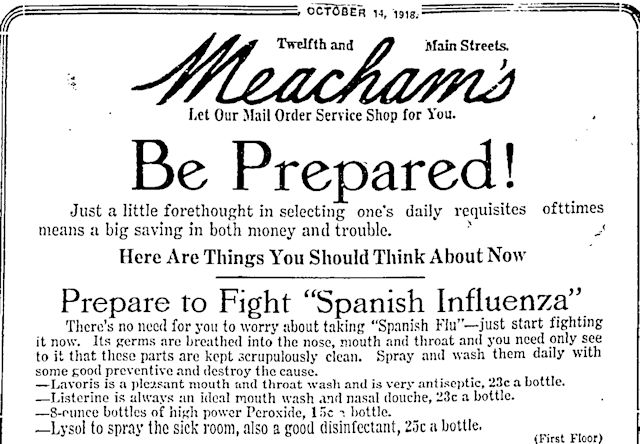

Advertising adapts to circumstance. Meacham’s Department Store advertised mouthwashes and disinfectants to fight influenza.

Advertising adapts to circumstance. Meacham’s Department Store advertised mouthwashes and disinfectants to fight influenza.

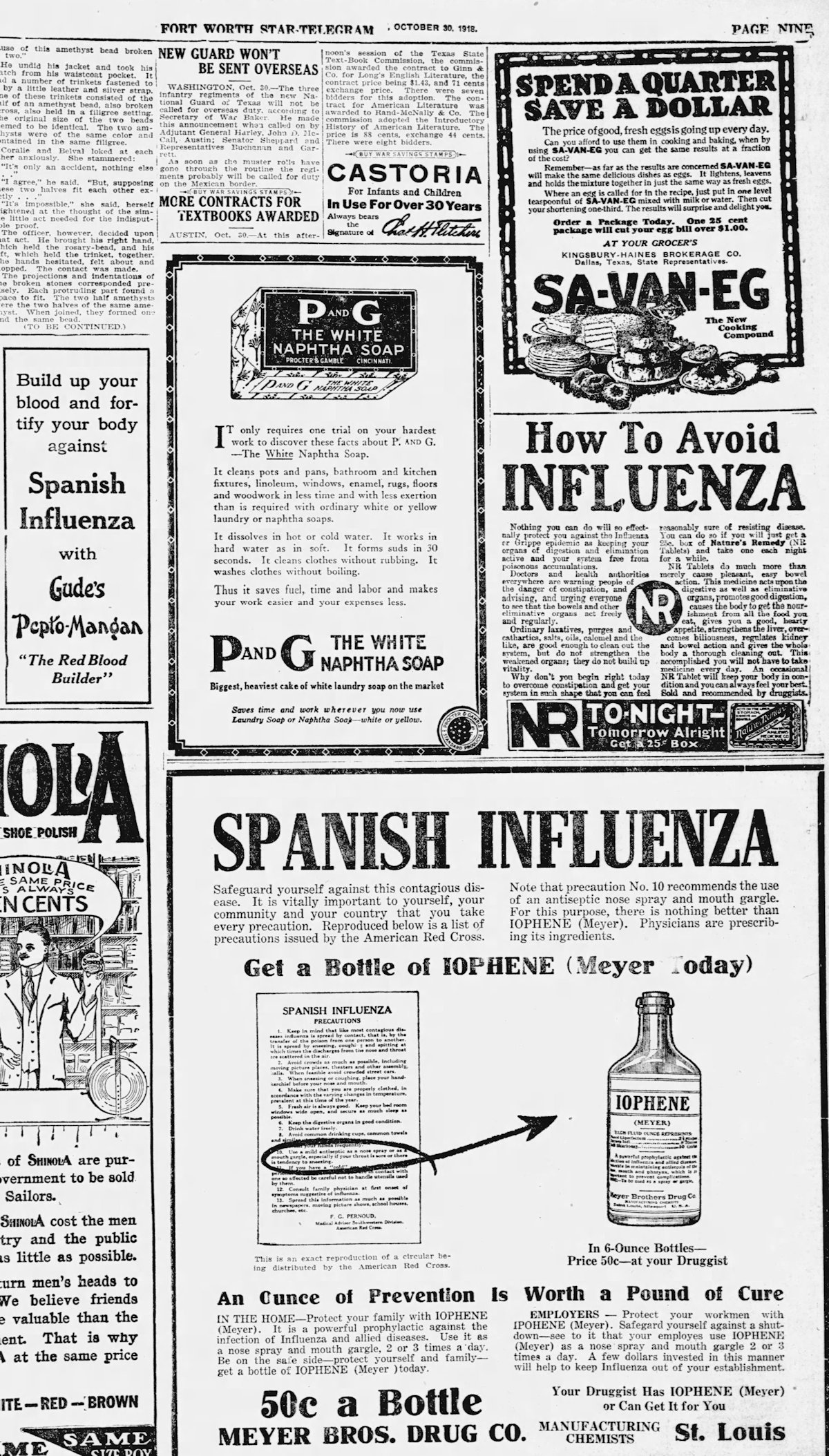

And, of course, patent medicines such as Nature’s Remedy, Iophene, and Pepto-Mangan were advertised as preventatives.

And, of course, patent medicines such as Nature’s Remedy, Iophene, and Pepto-Mangan were advertised as preventatives.

By mid-October fourteen hundred workers at the packing plants had influenza, creating a labor shortage.

By mid-October fourteen hundred workers at the packing plants had influenza, creating a labor shortage.

One of the first civilian deaths in the city was Louis I. Miller, general manager of the Fort Worth Record.

One of the first civilian deaths in the city was Louis I. Miller, general manager of the Fort Worth Record.

On October 16 Camp Bowie reported a decrease in the number of influenza cases: “only five” deaths in the last twenty-four hours.

On October 16 Camp Bowie reported a decrease in the number of influenza cases: “only five” deaths in the last twenty-four hours.

The situation at the camp may have seemed improved, but in the city, health authorities reported “no abatement” of the outbreak. “The overflow at all local hospitals continues,” the Star-Telegram wrote. The United States Public Health Service could not keep up with the cases.

The situation at the camp may have seemed improved, but in the city, health authorities reported “no abatement” of the outbreak. “The overflow at all local hospitals continues,” the Star-Telegram wrote. The United States Public Health Service could not keep up with the cases.

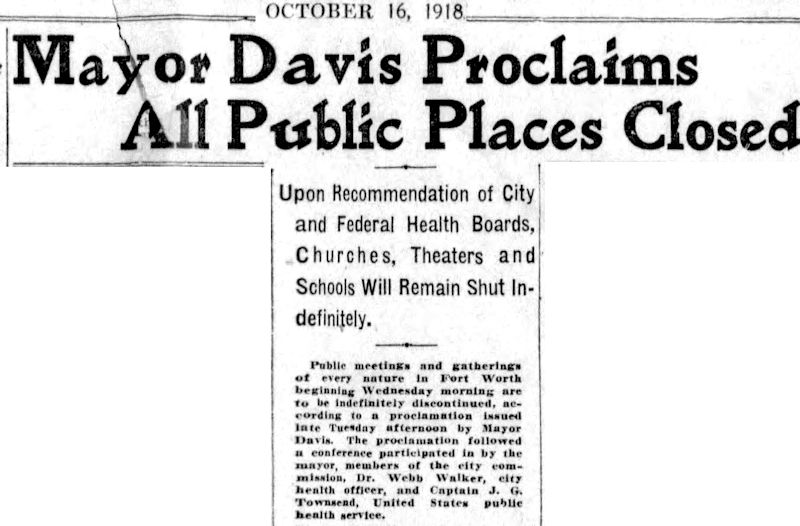

So, on October 16, the same day Camp Bowie reported a decrease in cases—thirteen days after the first death at the camp—the city, school board, and United States Public Health Service began a coordinated campaign to mitigate the outbreak.

Mayor William Davis signed a proclamation ordering all places of amusement to close and asked church congregations not to meet. Authorities advised people to stay at home, avoid crowds and public places. Don’t share towels and drinking vessels, don’t use public towels.

The school board reversed its thinking and closed schools for ten days.

Some private schools that remained open moved classes outdoors.

The state board of health urged schools that stayed open to disinfect all woodwork of school buildings. Students were urged to carry a clean handkerchief.

“Spitting on the floor, sneezing or coughing, except behind a handkerchief, should be sufficient grounds for suspension of a pupil,” the board advised.

“Public meetings and gatherings of every nature” were banned, the Record wrote, adding: “In addition to the closing of the places of public amusement and the abatement of church services officials ask that people refrain from visiting and that only such people as are absolutely necessary to carry on the commerce of the city leave their homes.”

“Public meetings and gatherings of every nature” were banned, the Record wrote, adding: “In addition to the closing of the places of public amusement and the abatement of church services officials ask that people refrain from visiting and that only such people as are absolutely necessary to carry on the commerce of the city leave their homes.”

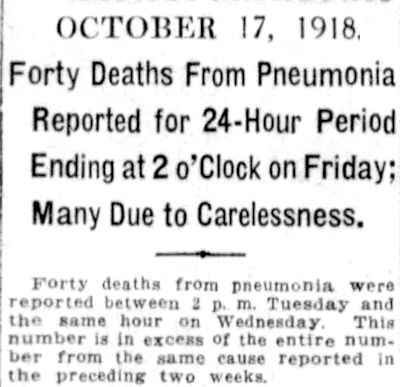

The next day a headline showed how urgently the campaign was needed: Forty deaths from pneumonia resulting from influenza were reported during a twenty-four-hour period on October 15-16—more than the number reported during the previous two weeks.

The next day a headline showed how urgently the campaign was needed: Forty deaths from pneumonia resulting from influenza were reported during a twenty-four-hour period on October 15-16—more than the number reported during the previous two weeks.

But Dr. Walker, city health officer, said some of those deaths could have been prevented by the victims. And he said that despite the death toll, he felt that the campaign—in effect just one day—was beginning to mitigate the outbreak.

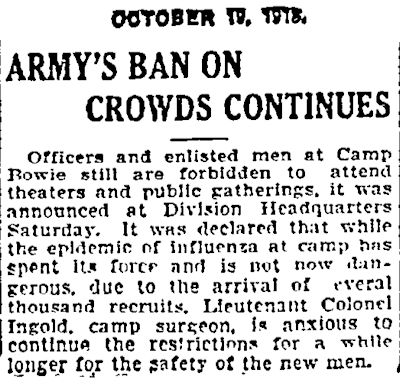

On October 19 health officers at Camp Bowie said the outbreak there had “spent its force.” But the restrictions on congregating would continue because of an influx of new soldiers.

On October 19 health officers at Camp Bowie said the outbreak there had “spent its force.” But the restrictions on congregating would continue because of an influx of new soldiers.

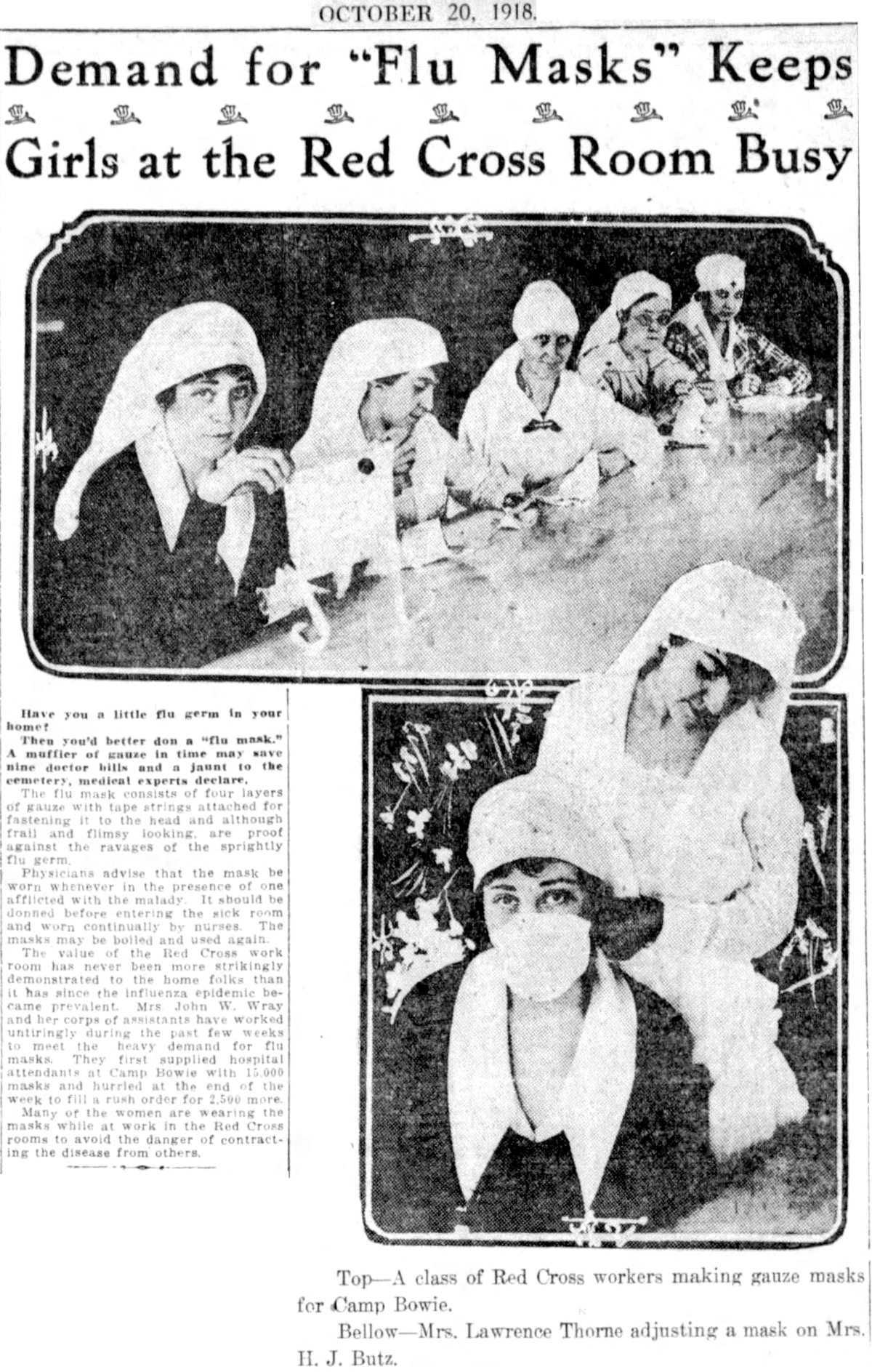

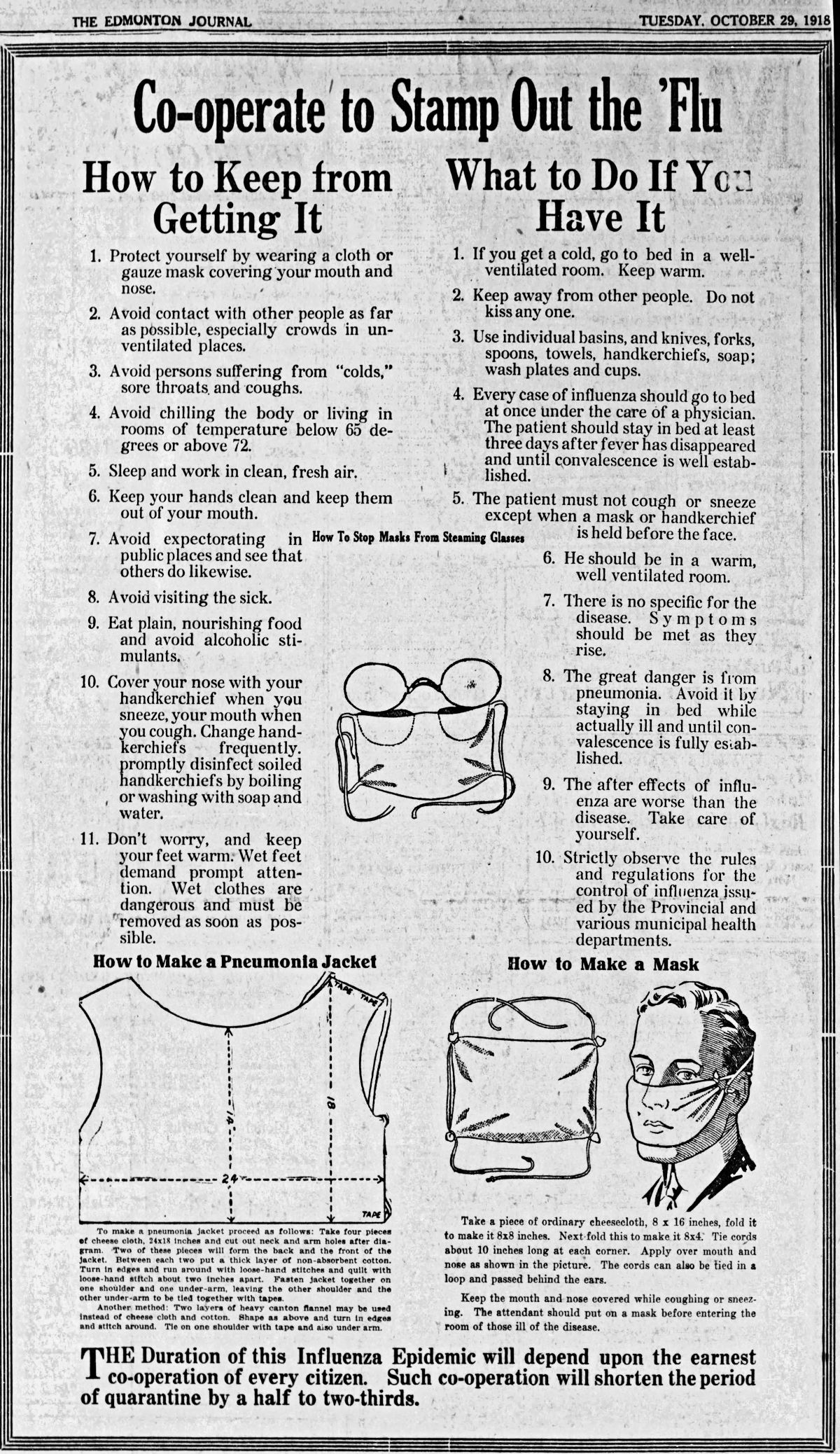

Meanwhile volunteers used the Red Cross workroom at Camp Bowie to make gauze masks for the camp. Authorities told the public that anyone coming in contact with an infected person should wear a mask.

Meanwhile volunteers used the Red Cross workroom at Camp Bowie to make gauze masks for the camp. Authorities told the public that anyone coming in contact with an infected person should wear a mask.

This how-to appeared in a Canadian newspaper.

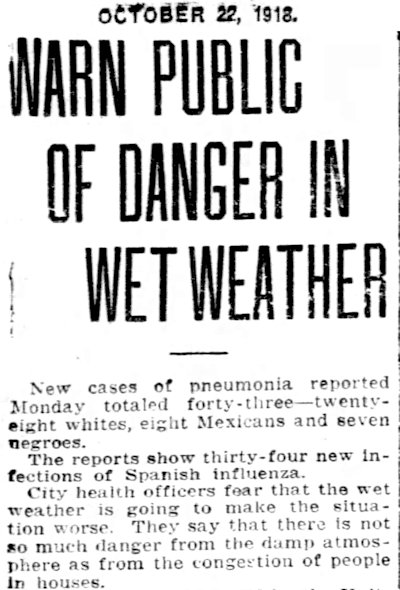

On October 22 Fort Worth authorities reported forty-three new cases of pneumonia and thirty-four of influenza.

On October 22 Fort Worth authorities reported forty-three new cases of pneumonia and thirty-four of influenza.

Authorities worried that wet weather was increasing close contact by driving people indoors.

Four days later Mayor Davis, declaring that “conditions have very greatly improved,” ended the city shutdown after ten days, and city schools reopened on October 28.

Four days later Mayor Davis, declaring that “conditions have very greatly improved,” ended the city shutdown after ten days, and city schools reopened on October 28.

Of course, the Star-Telegram and Record didn’t document just the impersonal statistics of the outbreak—the number of reported cases and deaths. The local newspapers also told the story of individuals and families. One family lost five members in a week.

Of course, the Star-Telegram and Record didn’t document just the impersonal statistics of the outbreak—the number of reported cases and deaths. The local newspapers also told the story of individuals and families. One family lost five members in a week.

The newspapers also personalized the outbreak in neighborhood roundups, reporting who was suffering from or recovering from the disease.

The newspapers also personalized the outbreak in neighborhood roundups, reporting who was suffering from or recovering from the disease.

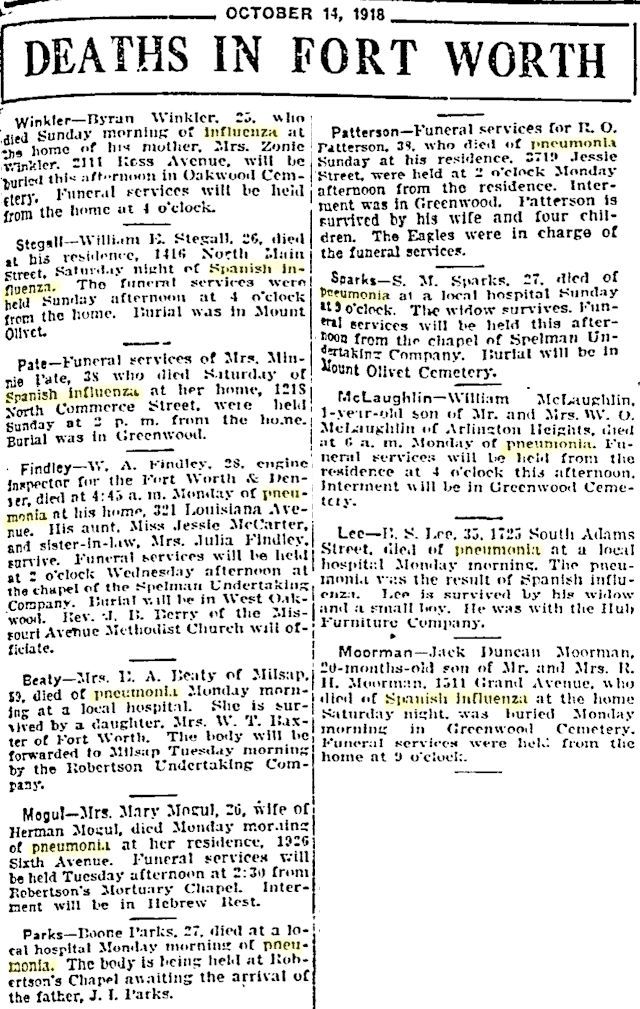

As well as those who did not recover. Twelve deaths from influenza or pneumonia were reported on October 14. The victims ranged in age from one to fifty-nine.

As well as those who did not recover. Twelve deaths from influenza or pneumonia were reported on October 14. The victims ranged in age from one to fifty-nine.

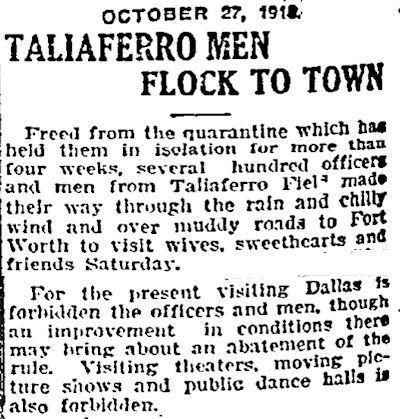

By October 27 the quarantine at Camp Taliaferro had been lifted enough that aviators could brave the wet weather to go into town to visit “wives, sweethearts and friends,” although aviators were still prohibited from entering places of amusement.

By October 27 the quarantine at Camp Taliaferro had been lifted enough that aviators could brave the wet weather to go into town to visit “wives, sweethearts and friends,” although aviators were still prohibited from entering places of amusement.

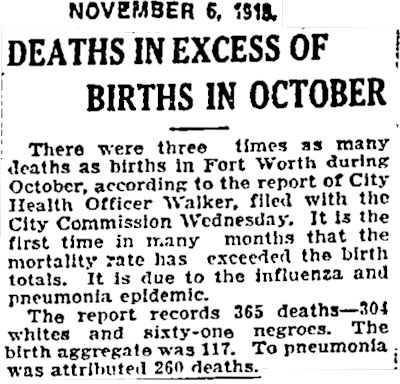

October was the peak month for both the military bases and the city. In Fort Worth 260 people died of pneumonia resulting from influenza—thirteen of them in one twenty-four-hour period. Because of the outbreak, in the month of October more people died than were born in Fort Worth.

October was the peak month for both the military bases and the city. In Fort Worth 260 people died of pneumonia resulting from influenza—thirteen of them in one twenty-four-hour period. Because of the outbreak, in the month of October more people died than were born in Fort Worth.

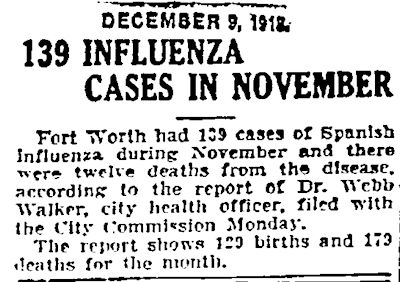

But only twelve deaths from influenza were reported in November.

But only twelve deaths from influenza were reported in November.

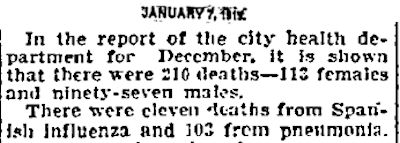

And in December, the city health department reported, there were only eleven deaths from influenza but 103 from pneumonia.

And in December, the city health department reported, there were only eleven deaths from influenza but 103 from pneumonia.

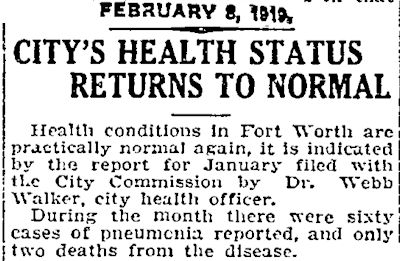

The other “world war” of 1918 continued into 1919 but soon abated in Fort Worth. Dr. Walker reported only sixty cases of pneumonia and only two deaths in January. The Star-Telegram declared the city’s health “practically normal again.”

The other “world war” of 1918 continued into 1919 but soon abated in Fort Worth. Dr. Walker reported only sixty cases of pneumonia and only two deaths in January. The Star-Telegram declared the city’s health “practically normal again.”

Locally, Dr. Walker reported that 699 residents had died from influenza or pneumonia resulting from influenza in 1918.

Globally, the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic was one of the deadliest disease outbreaks in recorded history. According to the Centers for Disease Control, an estimated 500 million people (one-third of the world’s population) became infected with the virus, “and the number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States. The pandemic was so severe that from 1917 to 1918, life expectancy in the United States fell by about 12 years, to 36.6 years for men and 42.2 years for women.”

In the military world war of 1914-1918 about twenty million soldiers and civilians died.

I too compliment you on this blog. “Diligence for information gathering” indeed.

I’ve been working on saving my dad’s memories, and his grandparents, etc. My great grandfather was JT Bryant, or John Thomas Bryant, came to Texas in 1873 or so, from Indian Territory and served on Ft Worth’ police department in 1877. Under Sheriff Courtright. Any info on him???

Thank you, Mr. Otto. I have e-mailed you several clips from 1877-1878 when your great-grandfather and Courtright were searching for Sam Bass and associates.

Very interesting. Have you written about the 1872/1873 equine influenza? Many thousands of horses caught it and some died. Boston had a major fire and young men had to haul the fire equipment, slowing the response. Farther west the U.S. Cavalry and the Apache were fighting on foot, horses on both sides being sick. From maps I have seen it made it to San Antonio and Galveston in December 1872. Did the Great Epizootic of 1872, as it is known, get to Fort Worth?

Thanks. Was not aware of that. Archived FW papers begin with 1873. Searching by various keywords, I find only this brief:

Fort Worth Democrat

February 15, 1873

SMALL-POX — We learn that the small-pox is prevailing at Longview; five deaths reported in one day. Hope it won’t reach Fort Worth, but as a stitch in time saves nine, we advise our citizens to get vaccinated forthwith. We also learn that cattle fed all winter are now dying of Epizootic in Tarrant County. Can’t somebody vaccinate the cattle.

Your blog is most interesting. I will have to come back to reread more carefully. Lots of information here. I admire your diligence for information gathering. My dad was in WW1, yes that is correct, WW1 NOT 2. He pushed through Europe from France with Pershing. Rode horseback and had night terrors from then till the day he died in 1967. He was a grandpas age when I was born. Anyway, great blog. Impressive

Thank you, Robin.