Will Rogers was many things to many people: cowboy, vaudeville performer, comedic star of stage, screen, and radio, newspaper columnist, social commentator.

To Oklahoma he was its “favorite son.” To Beverly Hills he was an honorary mayor. And to Fort Worth he was “just homefolks”—even if he never had a home here.

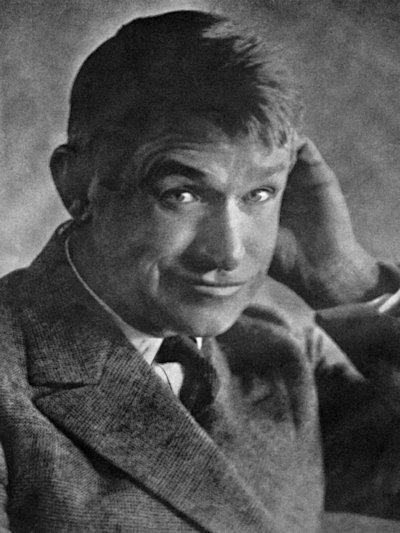

William Penn Adair Rogers was born in 1879 on the Dog Iron Ranch near Oologah, Oklahoma in what was then the Cherokee Nation of the Indian Territory. He would later claim Claremore as his birthplace “because nobody but an Indian can pronounce ‘Oologah.’” (Photo from Wikipedia.)

William Penn Adair Rogers was born in 1879 on the Dog Iron Ranch near Oologah, Oklahoma in what was then the Cherokee Nation of the Indian Territory. He would later claim Claremore as his birthplace “because nobody but an Indian can pronounce ‘Oologah.’” (Photo from Wikipedia.)

He was named for Cherokee Nation leader Colonel William Penn Adair. Rogers’s father, Clement Vann Rogers, himself was a Cherokee Nation senator and judge.

Will Rogers was one-quarter Cherokee. He liked to say that his ancestors didn’t come over on the Mayflower, but they “met the boat.”

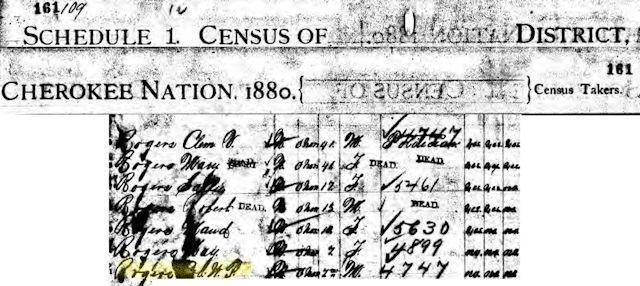

Rogers was seven months old when the 1880 census was taken.

Rogers was seven months old when the 1880 census was taken.

As a child Rogers was taught to rope and ride by an ex-slave. After dropping out of school in the tenth grade, Rogers left home to seek adventure: Texas Panhandle, South America, South Africa, Australia.

He began his show business career as the “Cherokee Kid,” a trick roper in Texas Jack’s Wild West Circus in, of all places, South Africa.

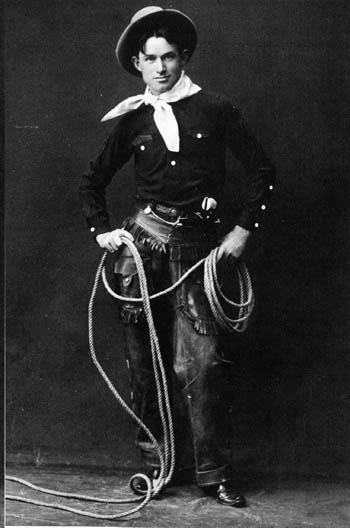

Will Rogers in the 1890s. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Will Rogers in the 1890s. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

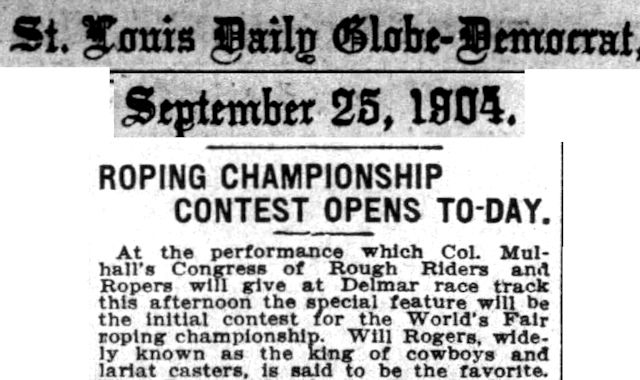

He returned to the United States in 1904, appeared at the St. Louis World’s Fair, and then joined the vaudeville circuits, where he performed riding and roping tricks.

He returned to the United States in 1904, appeared at the St. Louis World’s Fair, and then joined the vaudeville circuits, where he performed riding and roping tricks.

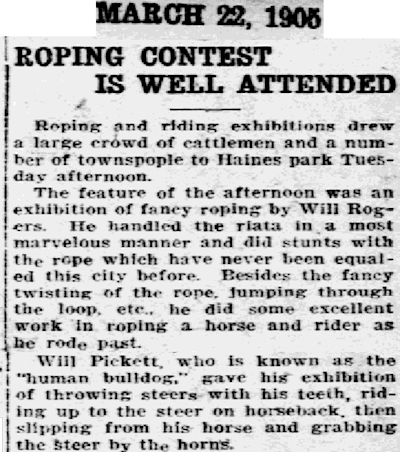

A year later Will Rogers passed through Fort Worth, performing at Haines Park.

A year later Will Rogers passed through Fort Worth, performing at Haines Park.

Note the mention of another Will: African-American rodeo performer Willie M. (“Bill”) Pickett.

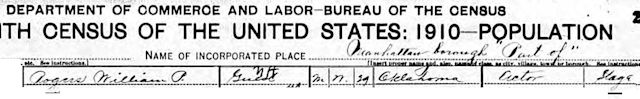

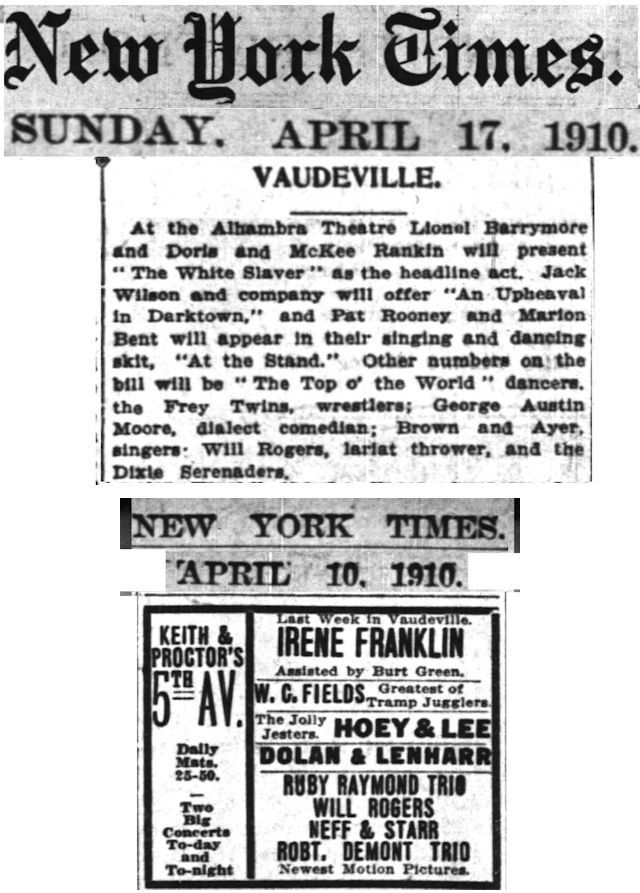

By 1910 the Cherokee Kid from Oologah had arrived in the city of “If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere”: New York City. He was living one block off Broadway in the theater district in a boardinghouse with several other actors.

By 1910 the Cherokee Kid from Oologah had arrived in the city of “If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere”: New York City. He was living one block off Broadway in the theater district in a boardinghouse with several other actors.

Rogers appeared in New York City theaters on bills with W. C. Fields and Lionel Barrymore.

Rogers appeared in New York City theaters on bills with W. C. Fields and Lionel Barrymore.

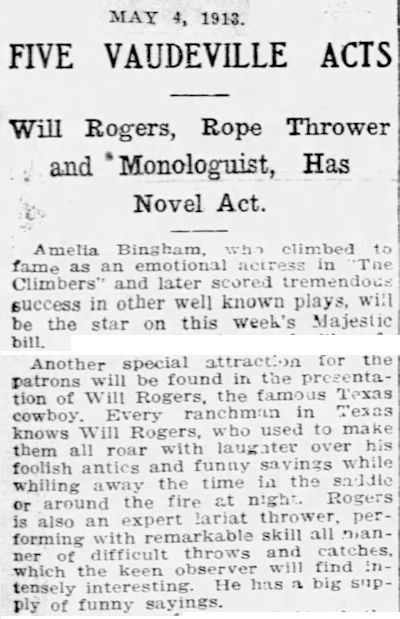

As quick as Rogers was with his hands and feet, he was even quicker with his wit. He soon added humorous monologues to his act. The lariat became just a prop, something to do with his hands as he told jokes. People came to see Rogers the comedian, not Rogers the cowboy. In 1913 he was back in town at the Majestic Theater at 10th and Commerce streets.

As quick as Rogers was with his hands and feet, he was even quicker with his wit. He soon added humorous monologues to his act. The lariat became just a prop, something to do with his hands as he told jokes. People came to see Rogers the comedian, not Rogers the cowboy. In 1913 he was back in town at the Majestic Theater at 10th and Commerce streets.

In 1915 Rogers joined Florenz Ziegfeld’s Midnight Frolic variety revue in New York City. By this time Rogers had refined his monologues. Oh, he still appeared on stage in his cowboy outfit. But now while he nonchalantly twirled his lasso he mused out loud about current events, especially politics.. “Well, what shall I talk about?” he’d ask his audience rhetorically. “I ain’t got anything funny to say. All I know is what I read in the papers.” Then he would offer laconic observations about what he had read in that day’s newspapers.

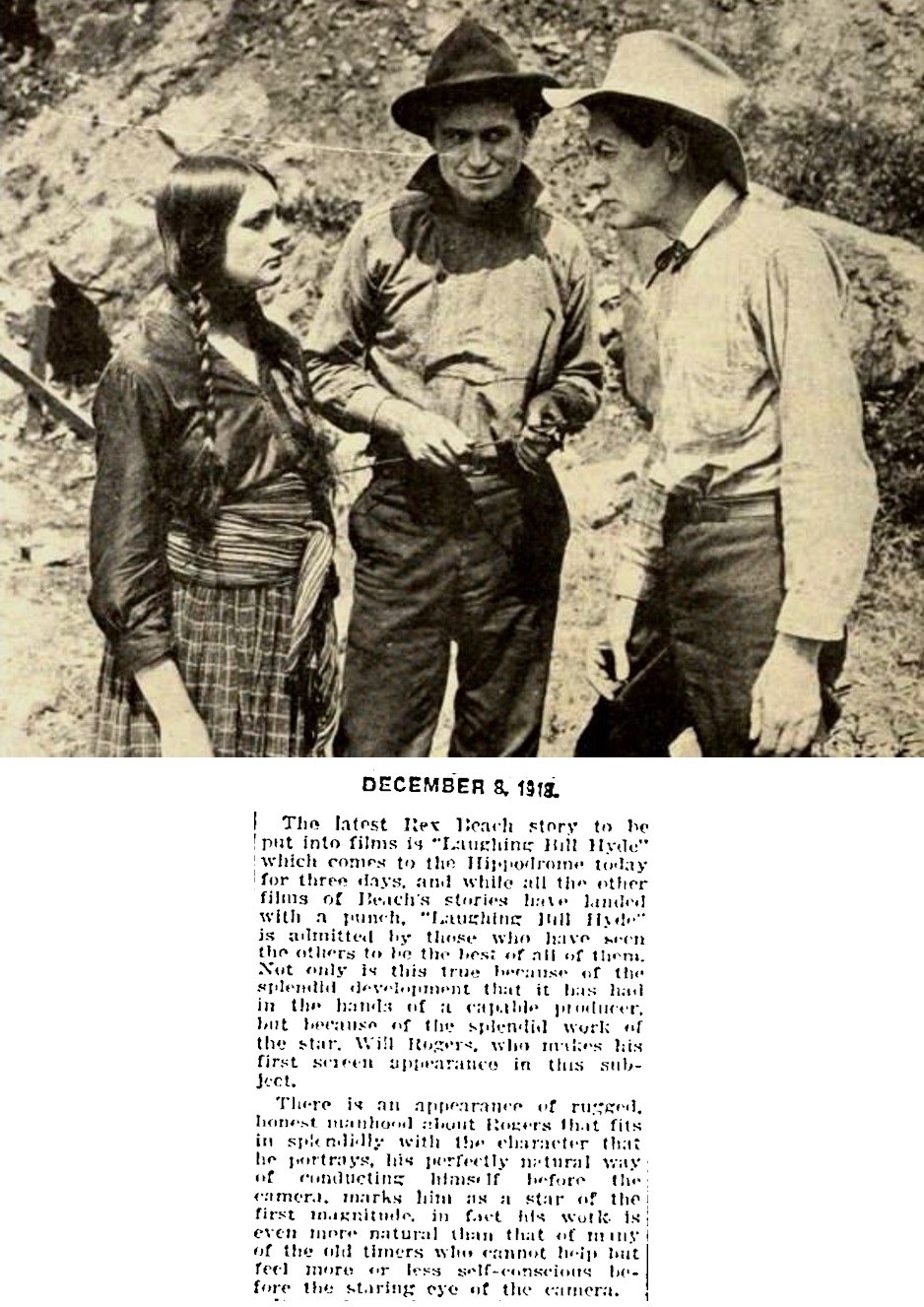

The next time Rogers returned to Fort Worth he was on the screen at the Hippodrome Theater in his first movie, Laughing Bill Hyde. The Star-Telegram reviewer noted “an appearance of rugged, honest manhood about Rogers.”

The next time Rogers returned to Fort Worth he was on the screen at the Hippodrome Theater in his first movie, Laughing Bill Hyde. The Star-Telegram reviewer noted “an appearance of rugged, honest manhood about Rogers.”

After Will Rogers and Hollywood discovered each other, he bought a ranch in Pacific Palisades and established his own production company. Rogers had become famous on stage because of his verbal ability. Although silent movies could not do justice to that ability, Rogers became a star, in part because he wrote many of the title cards that appeared in his films.

Not long after Rogers (1922 photo from Wikipedia) moved to California, the paths of two media meteors crossed in the sky on the other side of the country: The Cherokee Kid met the Cowtown cheerleader.

Not long after Rogers (1922 photo from Wikipedia) moved to California, the paths of two media meteors crossed in the sky on the other side of the country: The Cherokee Kid met the Cowtown cheerleader.

According to Jerry Flemmons in Amon: The Life of Amon Carter, Sr. of Texas, “Probably Amon and Will met in 1922 during a party at John McGraw’s house in New York.”

McGraw was manager of the New York Giants.

By 1922 Amon Carter was second in command at the Star-Telegram: vice president, general manager, a board member. By 1922 Will Rogers had made a dozen movies. The star of each man was rising, but, tracking separate trajectories, each star would rise much higher as each man become famous nationally.

The two men, Flemmons writes, became good friends. They were the same age (forty-three), both Democrats, both of a western disposition. Rogers had actually been a cowboy; Carter loved to “play at” being a cowboy.

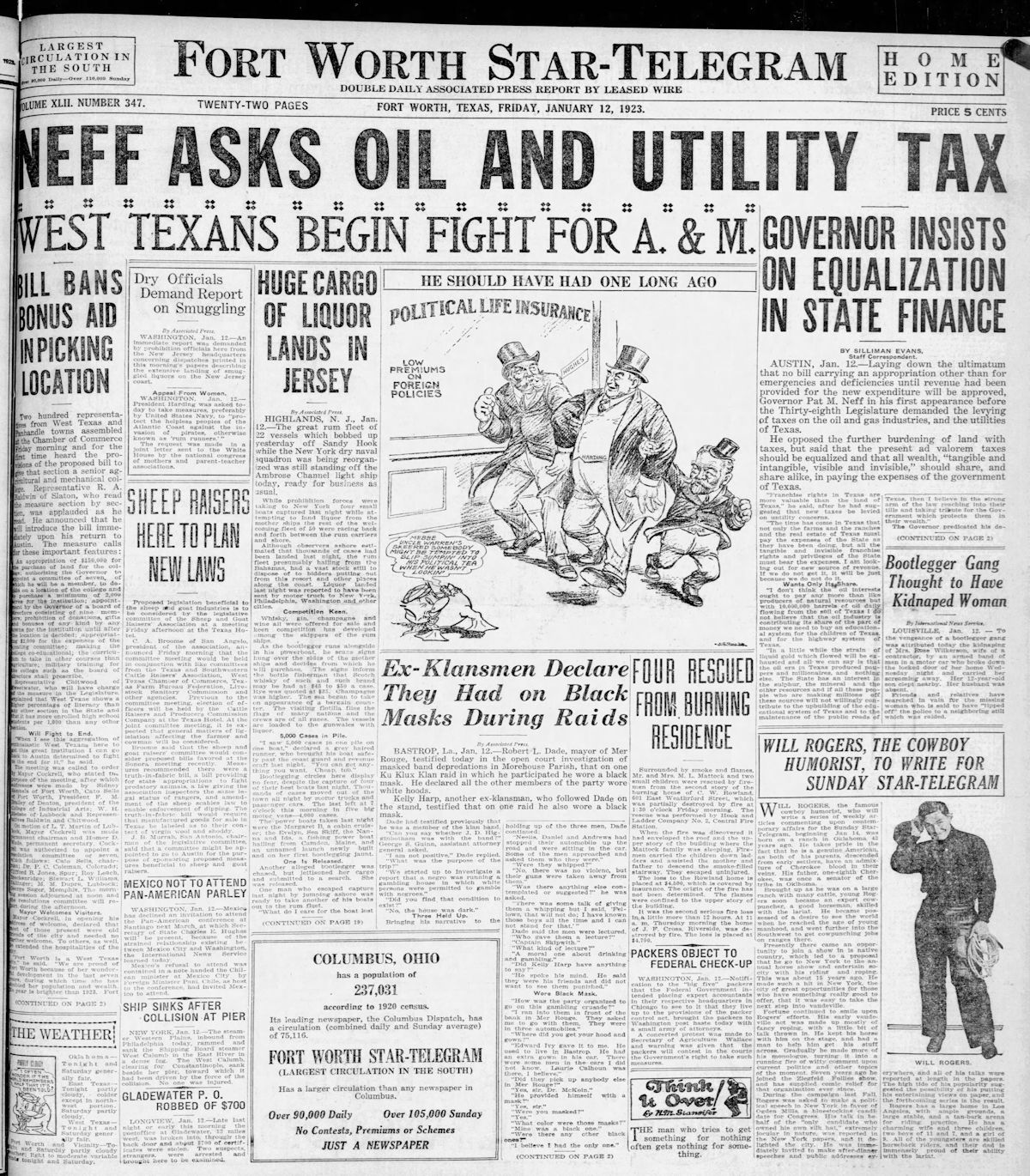

Not surprisingly, a year after Carter and Rogers met, the Star-Telegram was among the first newspapers in the country to print Rogers’s syndicated column.

Not surprisingly, a year after Carter and Rogers met, the Star-Telegram was among the first newspapers in the country to print Rogers’s syndicated column.

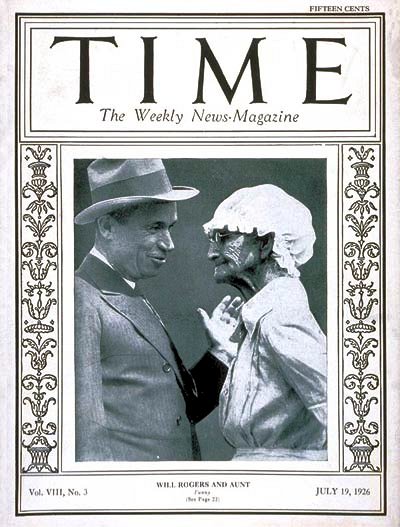

By the time Will Rogers was featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1926, he was a media star: personal appearances, movies, newspaper columns.

By the time Will Rogers was featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1926, he was a media star: personal appearances, movies, newspaper columns.

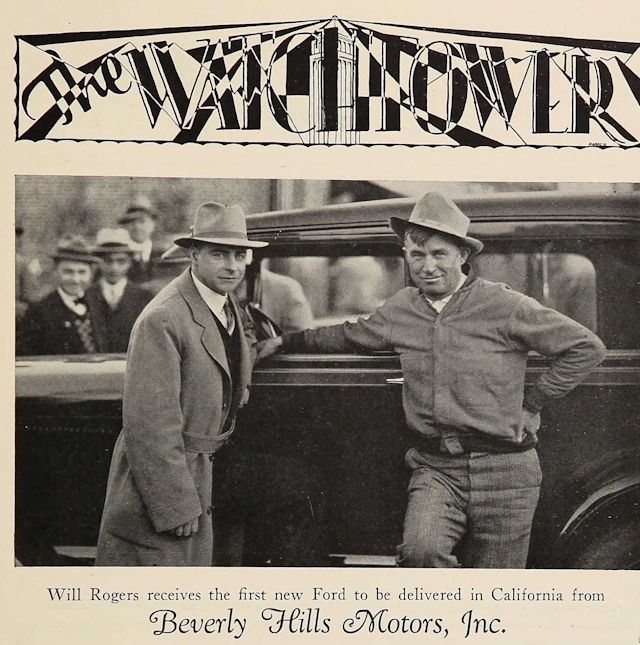

By 1928 Rogers was living in Beverly Hills, where he was honorary mayor. This ad appeared in the 1928 Watchtower, the yearbook of Beverly Hills High School, where his son Will Jr. was a student.

By 1928 Rogers was living in Beverly Hills, where he was honorary mayor. This ad appeared in the 1928 Watchtower, the yearbook of Beverly Hills High School, where his son Will Jr. was a student.

With the advent of sound movies, the star of Will Rogers soared even higher. Now audiences could hear that Oklahoma twang as Rogers beguiled with his “aw, shucks” persona. His first sound film, They Had to See Paris, opened in 1929 at the Majestic.

With the advent of sound movies, the star of Will Rogers soared even higher. Now audiences could hear that Oklahoma twang as Rogers beguiled with his “aw, shucks” persona. His first sound film, They Had to See Paris, opened in 1929 at the Majestic.

Politically Rogers may have been a Democrat, but he was an equal opportunity iconoclast:

“I always say nice things about folks—even Republicans, but I usually wait until the Republicans die. The quicker they die, the nicer I talk about them. There are a lot of dead Republicans that are good men.”

But also

“I am not a member of an organized political party. I am a Democrat.”

Will Rogers was becoming a latter-day Mark Twain.

Twain: “Suppose you were an idiot and suppose you were a member of Congress. But I repeat myself.”

Rogers: “A fool and his money are soon elected.”

Twain: “There is no distinctly native American criminal class except Congress.”

Rogers: “This country has come to feel the same when Congress is in session as when a baby gets hold of a hammer.”

Rogers poked fun freely, but his humor was seldom caustic. In 1930 he said, “When I die, my epitaph, or whatever you call those signs on gravestones, is going to read: ‘I joked about every prominent man of my time, but I never met a man I didn’t like.’ I am so proud of that, I can hardly wait to die so it can be carved.”

When Will Rogers visited Fort Worth he stayed in Carter’s suite at the Fort Worth Club or at Carter’s Shady Oak Farm at Lake Worth. Flemmons writes that Carter would hire a dozen cowboys and stage a rodeo for Rogers at Shady Oak.

“Rogers always involved himself in the rodeo, doing his lariat tricks, which often included roping a cigar from Amon’s mouth.”

When Rogers visited Shady Oak in 1931 Carter gave him a mounted steer head.

When Rogers visited Shady Oak in 1931 Carter gave him a mounted steer head.

Carter also visited Rogers’s California ranch.

And the two men met often in Washington, usually at the Mayflower Hotel. Flemmons writes: “Rogers once entered the Mayflower, surveyed the nodding elderly faces and solemn silence. He stood in the lobby’s center, cupped his hands and yelled: ‘Hooray for Amon Carter, Fort Worth and west Texas!’”

In 1931 Texas, like the rest of the nation, was suffering from the Great Depression. Much of Texas also was suffering from drought. According to Flemmons, Carter told Rogers about the double whammy.

In 1931 Texas, like the rest of the nation, was suffering from the Great Depression. Much of Texas also was suffering from drought. According to Flemmons, Carter told Rogers about the double whammy.

From California Rogers wired Carter: “Keep this to yourself and wire me at once how it sounds. I will come to Texas towns, [and] pay all my own expenses and donate all proceeds to unemployed . . .”

In response, Flemmons writes, Carter “offered a plane and pilot, the Star-Telegram, his radio station and ‘anything else in my power.’”

Rogers cleared his calendar and toured Texas giving speeches to raise money for the unemployed.

But Rogers also used his tour to poke a little fun at his friend. Amon Carter’s fondest dream was to see the Trinity River canalized from the gulf coast to Fort Worth. Carter was chairman of the executive committee of the Trinity River Canal Association.

Rogers said in one of his benefit speeches: “They told me when I was here to start my tour that they were going to bring the ocean right up to Fort Worth, seriously, no foolin’. The ocean right up to Fort Worth? I asked. Well, that is serious, I don’t suppose it’s ever been that far away from home before. So when I got in my plane and started for Austin, I asked the pilot to show me the Trinity River. After he’d pointed and pointed and I still couldn’t see anything, he got way down near the ground and said, ‘There!’ Well, the river wasn’t flowing, it was oozing. I’m afraid when you get your ocean up here, somebody’s going to drive a herd of cattle across it and drink it up.”

But Rogers respected Carter’s love of Fort Worth. “No other city in America,” Rogers said, “has anything approaching such a public citizen as Amon Carter.”

That benefit tour of 1931, the Star-Telegram later wrote, cemented the relationship between Will Rogers and Fort Worth. Rogers was impressed by the generosity of Fort Worth, which donated twice as much money as any other Texas city (and quadrupled the donation of Dallas); Fort Worth was impressed by the generosity of Rogers.

Also in 1931 Rogers asked Carter to give his son, then twenty, a job at the Star-Telegram. Carter consented.

“I’ll put the boy up at the Fort Worth Club until he can get located.”

“Don’t you do any fool thing like that!” Rogers protested. “Let him hunt up a good five-dollar-a-week boardinghouse.”

Will Jr. moved into Fort Worth’s YMCA and worked in the Star-Telegram‘s advertising department.

But Will Rogers Jr. didn’t exactly toil in anonymity during his time at the Star-Telegram.

But Will Rogers Jr. didn’t exactly toil in anonymity during his time at the Star-Telegram.

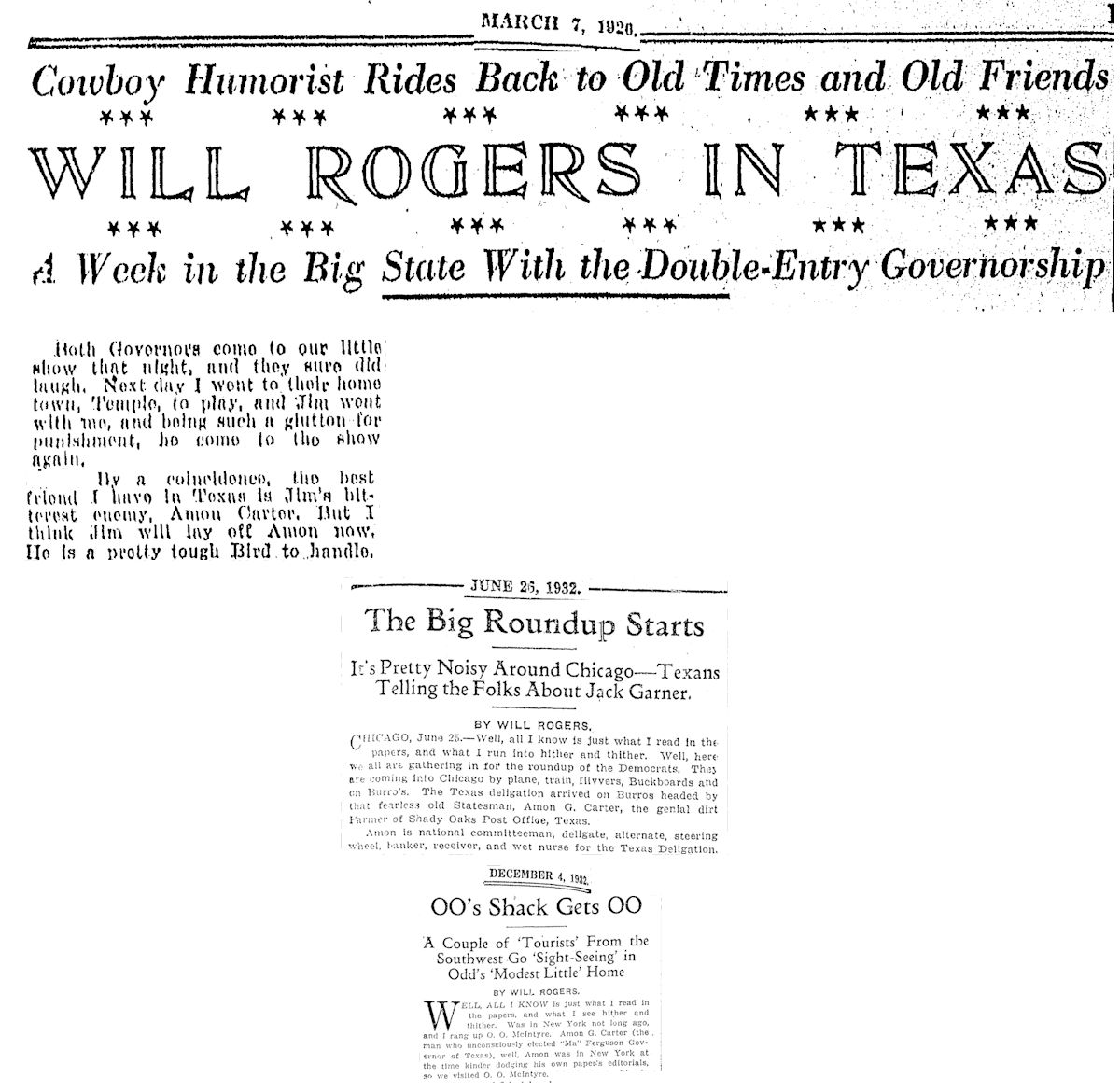

Will Rogers Sr. in his syndicated column often mentioned Amon Carter (“the best friend I have in Texas”). In these clips “Jim” was ex-governor James Ferguson; Rogers and Carter were in Chicago for the Democratic National Convention; Oscar Odd McIntyre was a New York newspaper columnist of the 1920s and 1930s who wrote under the byline “O. O. McIntyre.”

Will Rogers Sr. in his syndicated column often mentioned Amon Carter (“the best friend I have in Texas”). In these clips “Jim” was ex-governor James Ferguson; Rogers and Carter were in Chicago for the Democratic National Convention; Oscar Odd McIntyre was a New York newspaper columnist of the 1920s and 1930s who wrote under the byline “O. O. McIntyre.”

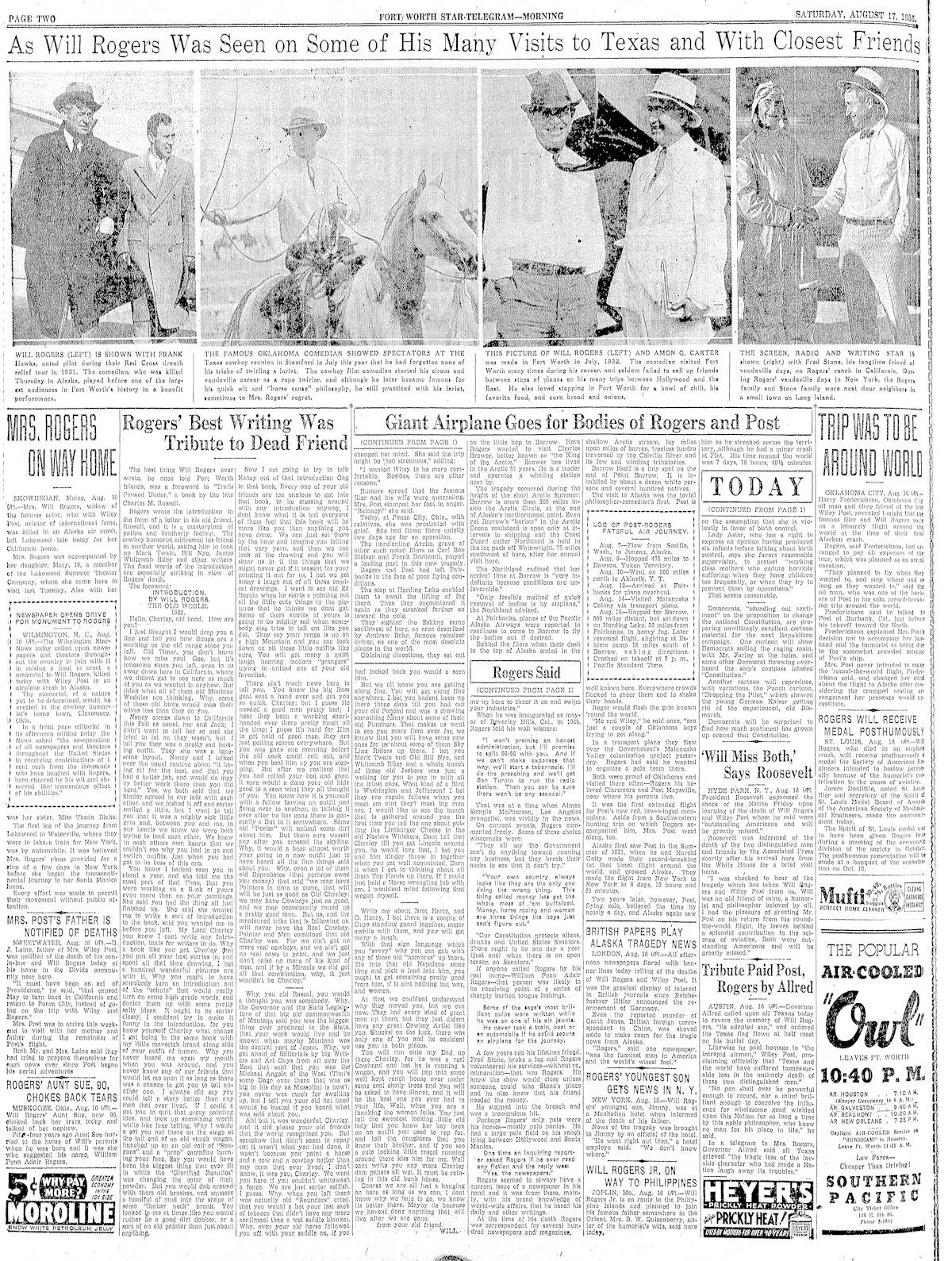

Fast company: From left, Frank Hawks, W. T. Waggoner, Will Rogers, and Amon Carter, early 1930s, at Waggoner’s Arlington Downs. Frank Hawks was a record-setting aviator known as the “fastest airman in the world.” When Rogers toured the state in 1931, Hawks was his pilot. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

Amon Carter with Will Rogers and another frequent visitor to Fort Worth, Eleanor Roosevelt.

Amon Carter with Will Rogers and another frequent visitor to Fort Worth, Eleanor Roosevelt.

By 1935 Rogers was a national celebrity, its leading political humorist, and the highest-paid Hollywood film star.

In July Rogers visited Fort Worth. He and Carter flew west to Stamford, where they attended the Texas Cowboy Reunion. Rogers stayed a few days in Carter’s suite in the Fort Worth Club.

Then Carter drove Rogers to the airport, Flemmons writes. “The plane was late, delayed in Chicago for sacks of mail to be loaded. Will fidgeted, anxious for the plane to arrive. ‘You have to remember,’ explained Amon. ‘You’re in the third greatest airmail center of America. They have to work all the airmail here.’ ‘Work it or write it?’ cracked Will, and soon he flew away.”

That was the last time Amon Carter or the rest of Will Rogers’s adopted hometown saw “just homefolks” alive.

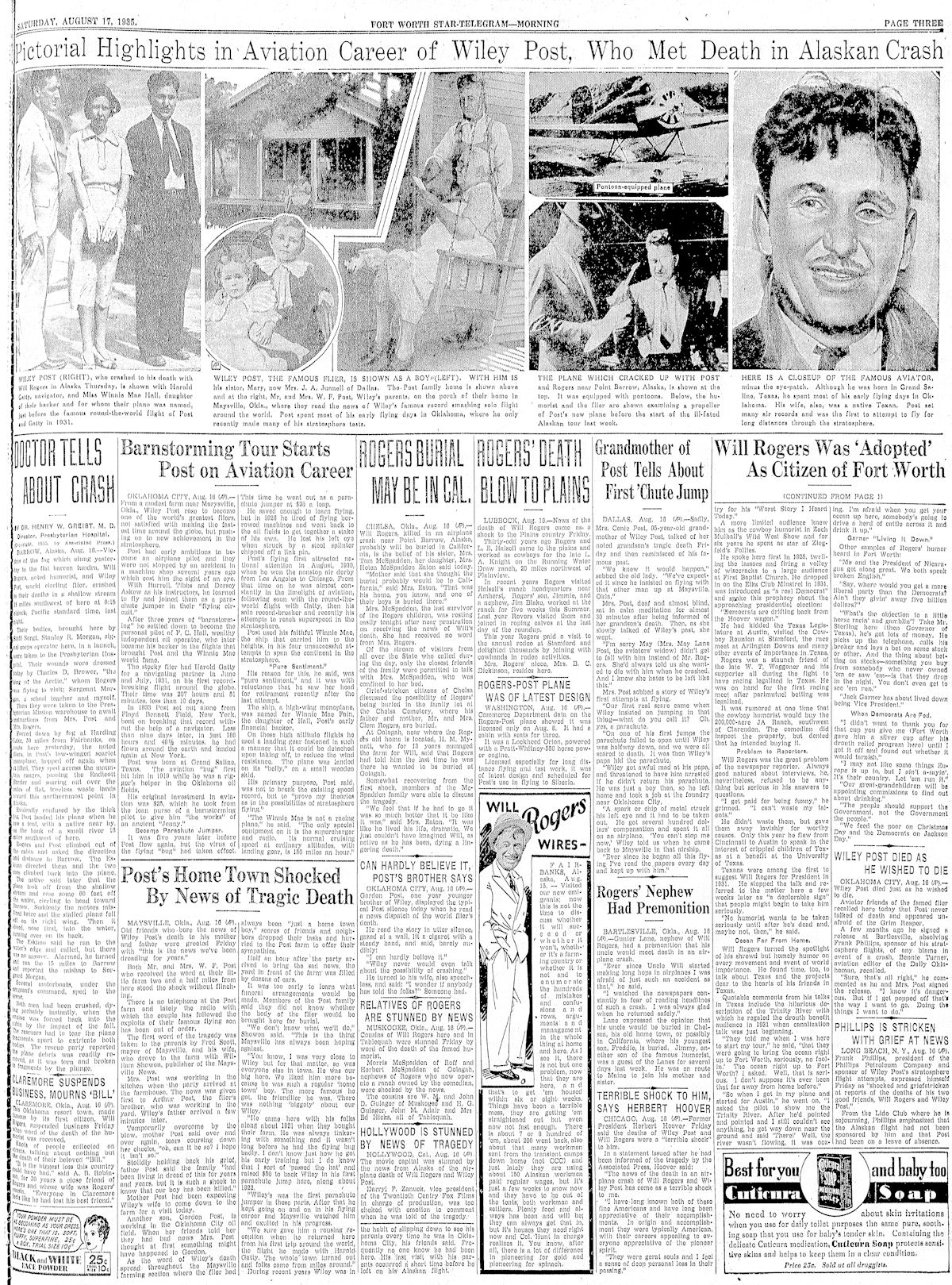

On August 7 Rogers flew north from Seattle with Wiley Post, another record-setting aviator. Post wanted to survey a mail-and-passenger air route from the West Coast to Russia. Rogers, an aviation enthusiast, asked to tag along to gather material for his syndicated newspaper column. In the photo, Rogers (wearing hat) stands on the wing of the airplane of Post (wearing eye patch) in Alaska. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

On August 7 Rogers flew north from Seattle with Wiley Post, another record-setting aviator. Post wanted to survey a mail-and-passenger air route from the West Coast to Russia. Rogers, an aviation enthusiast, asked to tag along to gather material for his syndicated newspaper column. In the photo, Rogers (wearing hat) stands on the wing of the airplane of Post (wearing eye patch) in Alaska. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

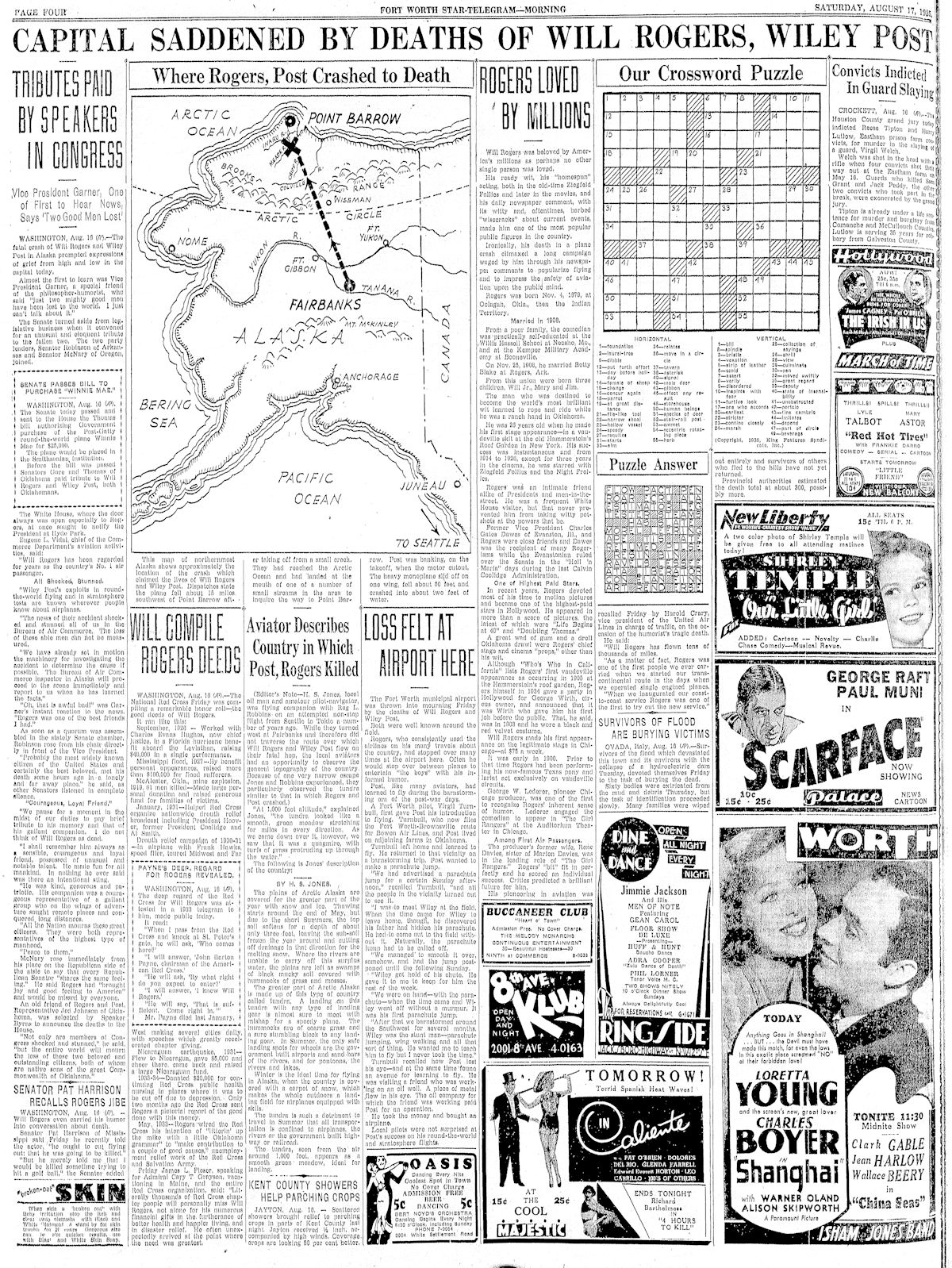

On August 13 a brief on the front page of the Star-Telegram reported that Rogers and Post had reached Yukon Territory, Canada.

On August 13 a brief on the front page of the Star-Telegram reported that Rogers and Post had reached Yukon Territory, Canada.

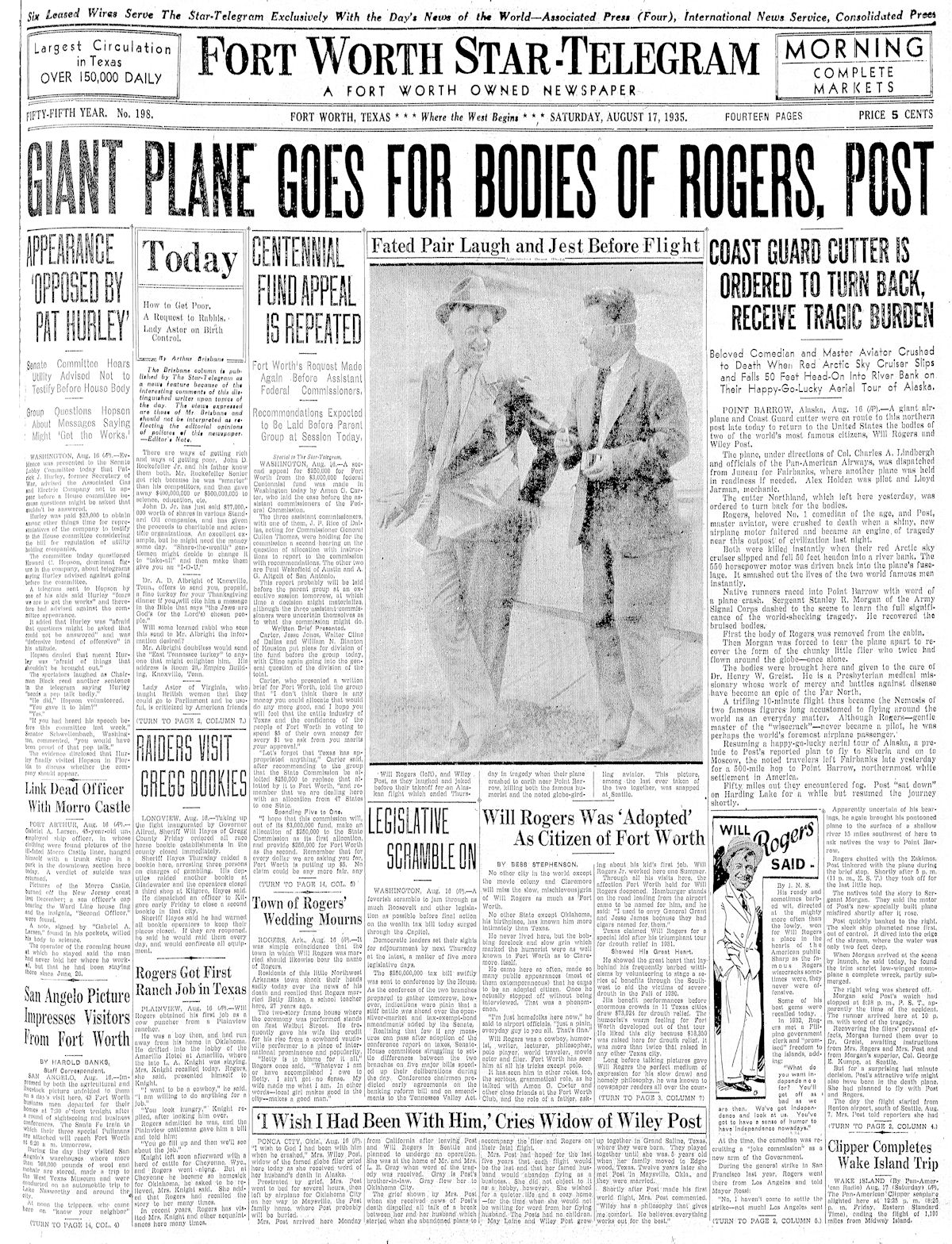

Four days later that brief had exploded into a front page of shock and grief. Will Rogers and Wiley Post had been killed when their airplane crashed shortly after takeoff from a lagoon near Point Barrow.

Four days later that brief had exploded into a front page of shock and grief. Will Rogers and Wiley Post had been killed when their airplane crashed shortly after takeoff from a lagoon near Point Barrow.

The Star-Telegram wrote:

“POINT BARROW, Alaska, Aug. 18 (AP)—A giant airplane and Coast Guard cutter were en route to this northern post late today to return to the United States the bodies of two of the world’s most famous citizens, Will Rogers and Wiley Post.

“Rogers, beloved No. 1 comedian of the age, and Post, master aviator, were crushed to death when a shiny new airplane motor faltered and became an engine of tragedy near this outpost of civilization late night.”

The Star-Telegram wrote of Fort Worth’s love of its adopted son:

“No other city in the world, except the movie colony and Claremore, will miss the slow, mischievous grin of Will Rogers as much as Fort Worth.

“No other state except Oklahoma, his birthplace, has known him more intimately than Texas. He never lived here, but the bobbing forelock and slow grin which marked the humorist were as well known to Fort Worth as to Claremore itself.

“He came here so often, made so many public appearances, that he came to be an adopted citizen. He once said of his second home: ‘I’m just homefolks here now, just a plain, everyday guy to you all. That’s fine.’”

Amon Carter’s Star-Telegram devoted the first four pages of a fourteen-page edition to Rogers and Post.

Amon Carter’s Star-Telegram devoted the first four pages of a fourteen-page edition to Rogers and Post.

Although Rogers’s life was cut short at age fifty-five, he had traveled around the world three times, appeared in dozens of movies, and written more than four thousand nationally syndicated newspaper columns.

His tombstone bears the epitaph he had dictated in 1930.

His tombstone bears the epitaph he had dictated in 1930.

Tomorrow: “Beloved No. 1 Comedian” (Part 2): Fort Worth Remembers