After Will Rogers was killed in 1935 (see Part 1) a grieving nation began to honor the memory of its favorite humorist.

As a result, today there are schools, highways, hospitals, airports, and one Navy submarine named for him. He was featured on a postage stamp in 1948 and 1979. He has two stars (radio, film) on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. There is a shrine in Colorado, a memorial park in Beverly Hills (where Rogers lived and was honorary mayor), a memorial to Rogers and aviator Wiley Post in Alaska.

As a result, today there are schools, highways, hospitals, airports, and one Navy submarine named for him. He was featured on a postage stamp in 1948 and 1979. He has two stars (radio, film) on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. There is a shrine in Colorado, a memorial park in Beverly Hills (where Rogers lived and was honorary mayor), a memorial to Rogers and aviator Wiley Post in Alaska.

Of course, Claremore, Oklahoma, which claims Rogers as its own, has a museum and memorial (where he is buried). Rogers had bought the land in 1911 as his retirement property.

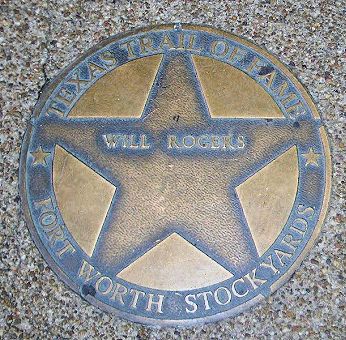

A third star honoring Rogers is embedded in Cowtown’s Texas Trail of Fame at the stockyards.

A third star honoring Rogers is embedded in Cowtown’s Texas Trail of Fame at the stockyards.

But Fort Worth’s main tribute to Will Rogers is the south side of the 3300 block of West Lancaster Avenue.

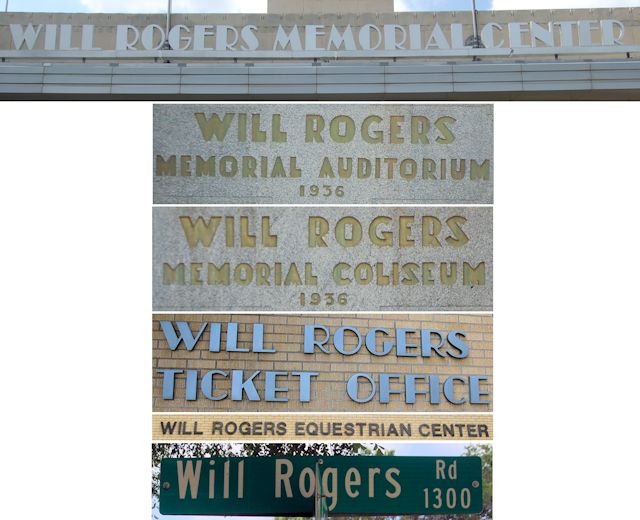

As you walk the grounds of Will Rogers Memorial Center and see his name everywhere, you might conclude that Rogers had been born in Fort Worth. Or at least lived here. Actually he was an adopted son of Fort Worth. He visited Cowtown so often that he said residents here regarded him as “just homefolks.”

As you walk the grounds of Will Rogers Memorial Center and see his name everywhere, you might conclude that Rogers had been born in Fort Worth. Or at least lived here. Actually he was an adopted son of Fort Worth. He visited Cowtown so often that he said residents here regarded him as “just homefolks.”

And he visited here often in part because he was a friend of Star-Telegram publisher Amon Carter.

Here’s how Will Rogers Memorial Center came to be.

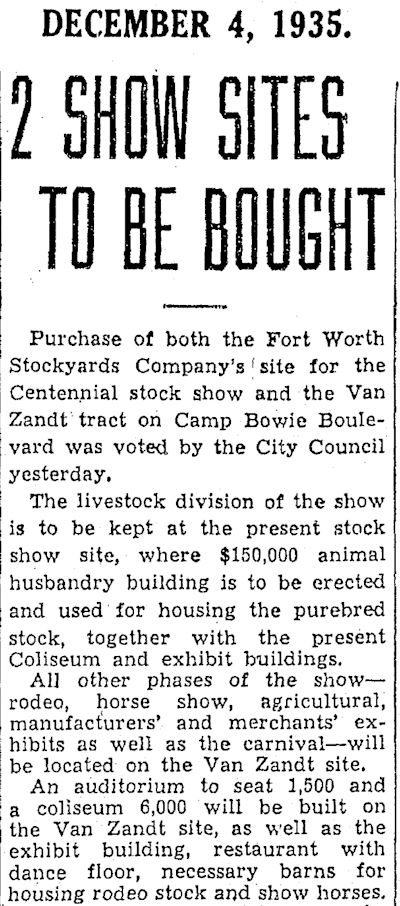

Even before Rogers died in 1935, Amon Carter and Fort Worth officials were planning a celebration of the Texas centennial the next year. Dallas had been chosen to host the official state celebration, but Fort Worth received $250,000 from the state centennial commission for its own celebration. Now Amon Carter the town’s head cheerleader became Amon Carter the town’s head cajoler. He cajoled his rich friends into writing fat checks. He also cajoled his friends in high places in Washington until he procured some Public Works Administration money, too. In addition to government funds, Fort Worth residents would chip in $1.2 million ($23 million today) by buying bonds and making donations.

In late 1935 the city bought a tract of land that once had belonged to Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt. Fort Worth planned to build a venue there for its centennial celebration, which would memorialize the Lone Star State’s livestock industry with a rodeo and horse show.

In late 1935 the city bought a tract of land that once had belonged to Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt. Fort Worth planned to build a venue there for its centennial celebration, which would memorialize the Lone Star State’s livestock industry with a rodeo and horse show.

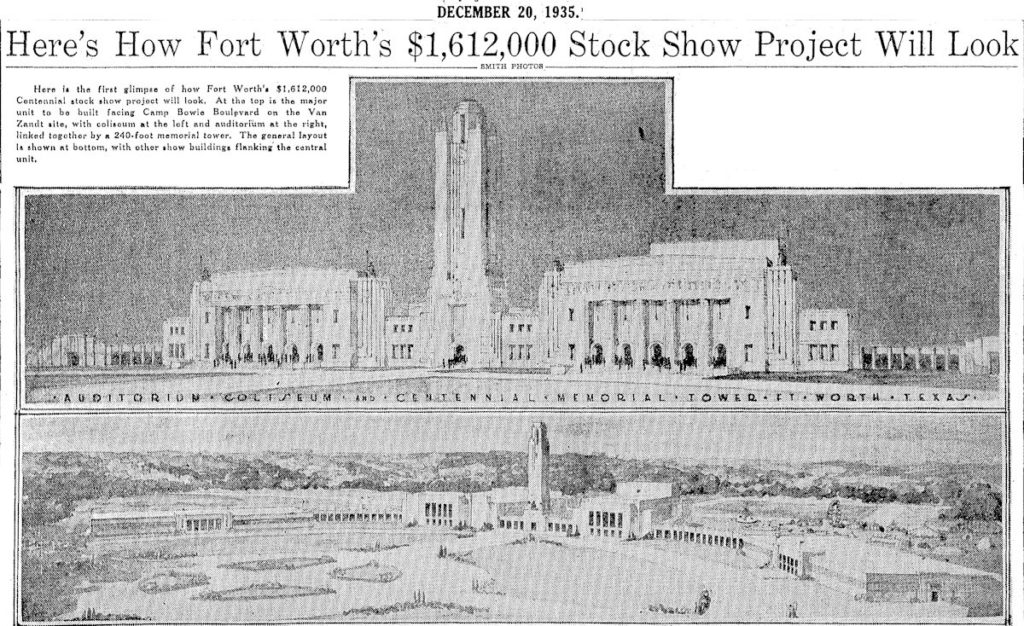

In December 1935 the Star-Telegram published architect Wyatt Hedrick’s sketches of the proposed venue, the three main elements being an auditorium and a coliseum and, between them, the 208-foot Pioneer Tower.

In December 1935 the Star-Telegram published architect Wyatt Hedrick’s sketches of the proposed venue, the three main elements being an auditorium and a coliseum and, between them, the 208-foot Pioneer Tower.

By early 1936 the plans for the centennial celebration had become more ambitious. Now it would include a frontier theme, with Native American and Mexican villages, range scenes, a museum of pioneer relics, a typical main street of a frontier town.

By early 1936 the plans for the centennial celebration had become more ambitious. Now it would include a frontier theme, with Native American and Mexican villages, range scenes, a museum of pioneer relics, a typical main street of a frontier town.

No one liked to play cowboy more than Amon Carter, but he ho-hummed a centennial celebration focused on livestock and frontier life. He wanted razzle, dazzle, and a heapin’ helpin’ of “hubba hubba,” especially in comparison with the stately official state centennial celebration in Dallas.

No one liked to play cowboy more than Amon Carter, but he ho-hummed a centennial celebration focused on livestock and frontier life. He wanted razzle, dazzle, and a heapin’ helpin’ of “hubba hubba,” especially in comparison with the stately official state centennial celebration in Dallas.

He wanted Fort Worth to out-Dallas Dallas.

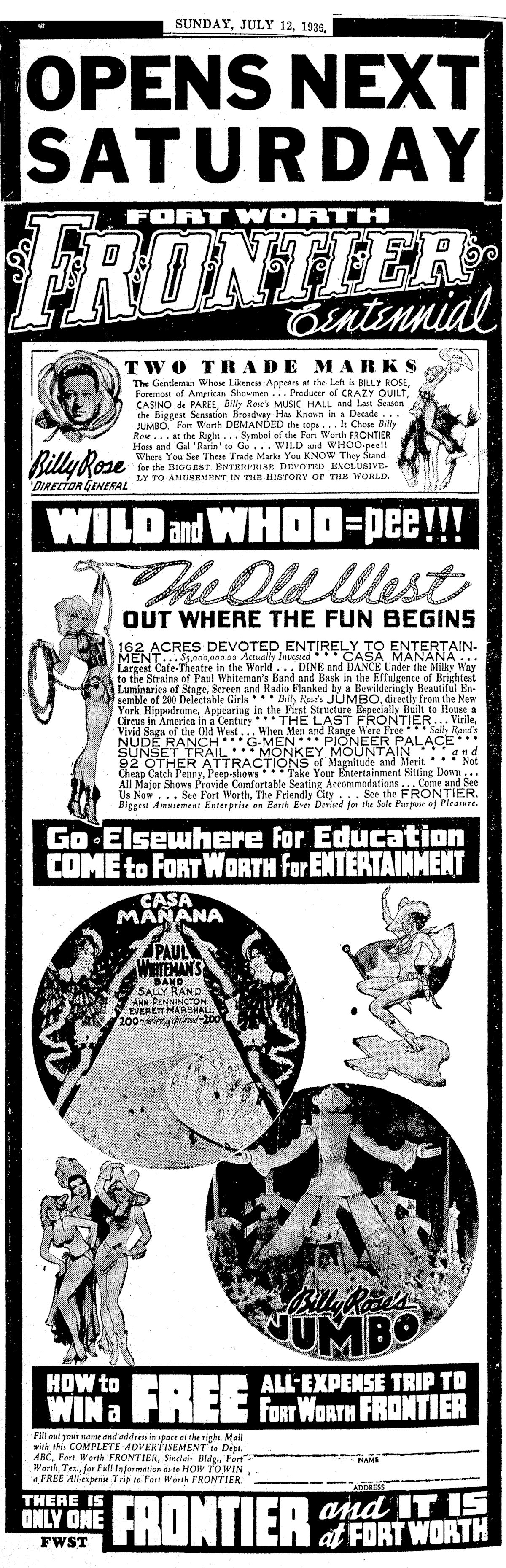

So he brought in famed theatrical showman Billy Rose to spice up the centennial celebration.

“Go elsewhere for education, come to Fort Worth for entertainment” became the tagline of newspaper ads for Fort Worth’s Frontier Centennial.

Eventually the Frontier Centennial included the circus musical “Jumbo” with lions, elephants, trapeze artists, clowns, and Monkey Mountain. There was the original Casa Manana with its revolving stage. There were Paul Whiteman and his orchestra, Ray Bolger, Don Ameche, and a steam locomotive. Canals, drawbridges, fountains, and pools. A gay nineties revue, the Silver Dollar Saloon, and the Big Berthas and Six Tiny Rosebuds (two plus-sized women’s dance troupes). Slot machines, marionettes, two women tapping out tunes on suspended liquor bottles, and side shows with such titles as “Gone with the Wind,” “Lost Horizon,” and “Boudoir Secrets.”

And “Girls! Girls! Girls!” Chief among them being fan-dancer Sally Rand and her Nude Ranch dancers.

Amon Carter is said to have seen Sally’s act sixty times.

Of course, one element was missing from the celebration: Will Rogers. Had he lived, surely Amon Carter would have arranged for Rogers to appear at the Frontier Centennial.

But Carter got the next-best thing for the celebration: a replica of the den of Will Rogers’s California ranch house. It included his saddle, easy chair, a Navajo rug, a light fixture fashioned from a wagon wheel, a photo of Rogers standing on the wing of the plane he died in (possibly the photo in Part 1), all on loan from Rogers’s widow.

The Frontier Centennial had been open one month when the gaiety paused briefly as Amon Carter and E. M. Waits of TCU eulogized their friend in the replica of his ranch house den. The tribute was broadcast on WBAP radio.

The Frontier Centennial had been open one month when the gaiety paused briefly as Amon Carter and E. M. Waits of TCU eulogized their friend in the replica of his ranch house den. The tribute was broadcast on WBAP radio.

Also on WBAP the Light Crust Doughboys dedicated a program to the memory of Rogers.

The next month the first of the new buildings to open was dedicated. Amon Carter announced that the new coliseum would be named in honor of his friend Will Rogers.

The next month the first of the new buildings to open was dedicated. Amon Carter announced that the new coliseum would be named in honor of his friend Will Rogers.

The first event to be staged in the coliseum would be the Frontier Centennial horse show.

Some views of the Will Rogers Memorial Center:

In a garden in front of these buildings stands a statue.

In a garden in front of these buildings stands a statue.

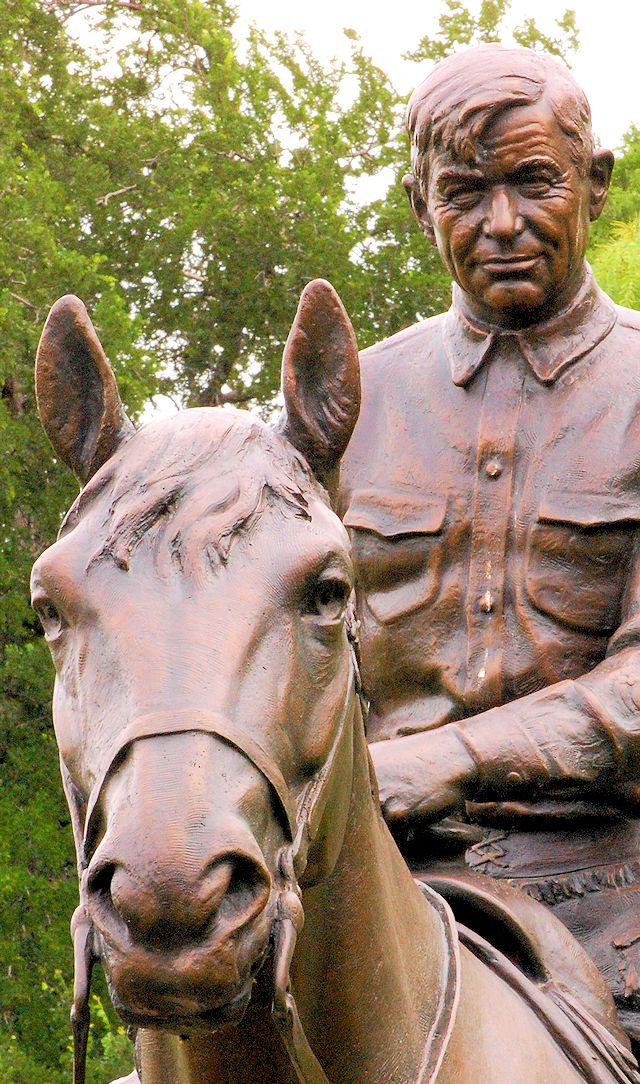

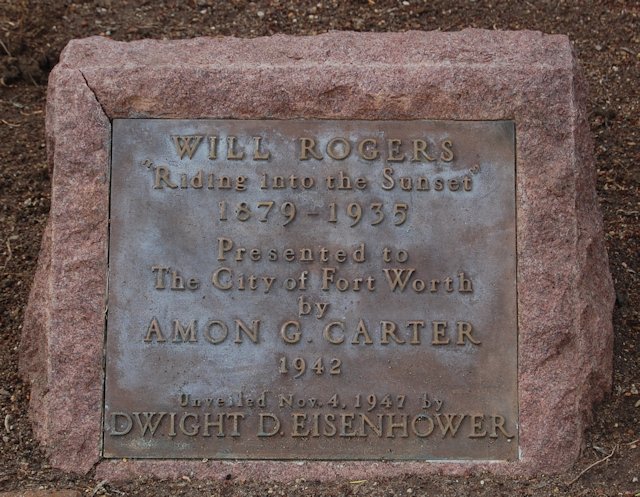

The statue, depicting Rogers and his horse Soapsuds, is entitled Riding Into the Sunset. It was created by sculptress and ranch heiress Electra Waggoner Biggs (granddaughter of W. T. Waggoner and niece of his daughter Electra Waggoner of Thistle Hill).

The statue, depicting Rogers and his horse Soapsuds, is entitled Riding Into the Sunset. It was created by sculptress and ranch heiress Electra Waggoner Biggs (granddaughter of W. T. Waggoner and niece of his daughter Electra Waggoner of Thistle Hill).

Amon Carter commissioned the statue in 1937. Biggs rented a New York City police horse as her model and consulted with a veterinarian to be sure of her equine anatomy.

Amon Carter commissioned the statue in 1937. Biggs rented a New York City police horse as her model and consulted with a veterinarian to be sure of her equine anatomy.

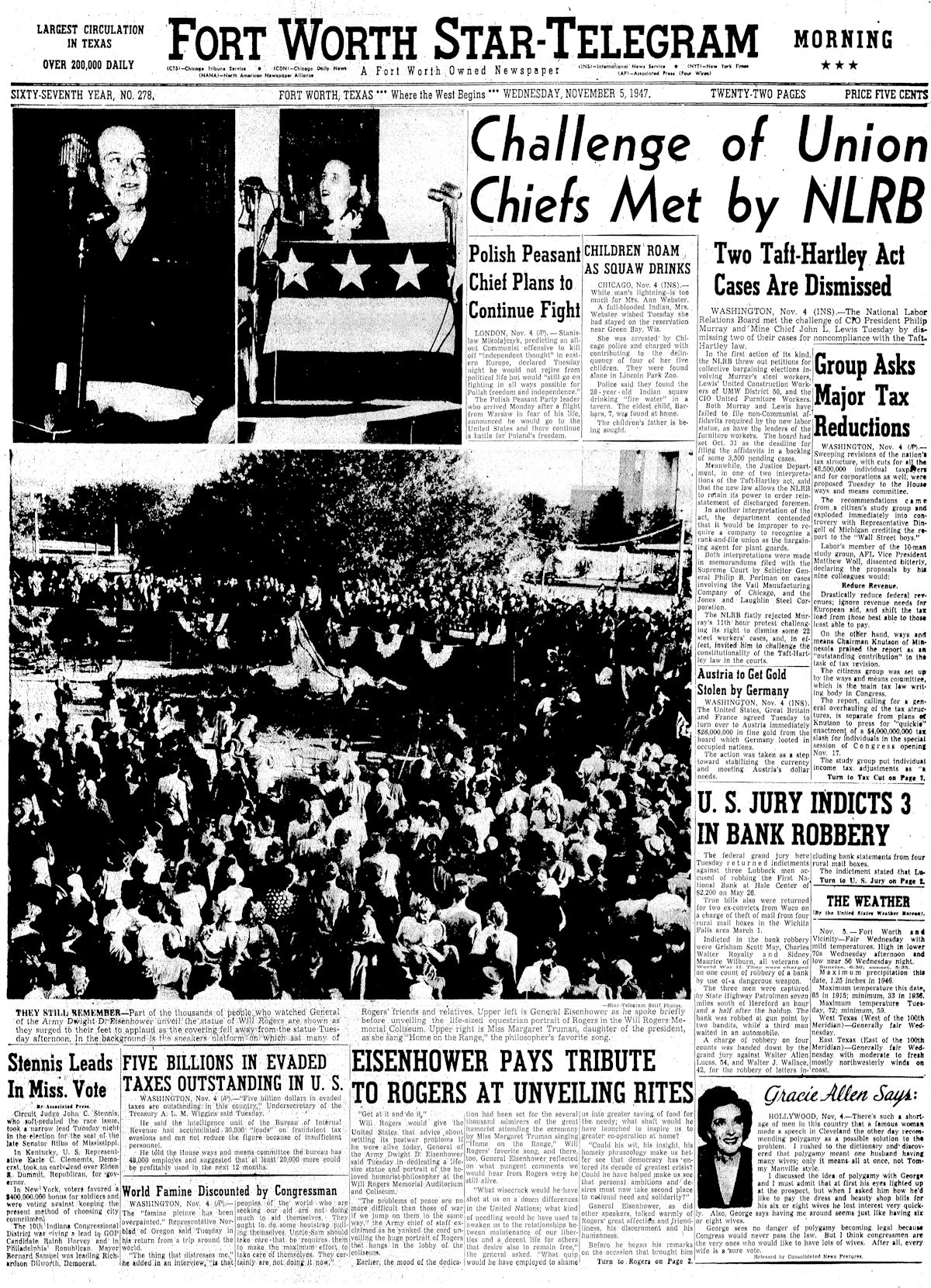

Riding Into the Sunset was installed in 1942 but kept crated and not dedicated until 1947, when Margaret Truman, daughter of the president, sang “Home on the Range,” Rogers’s favorite song, and General Dwight David Eisenhower wondered aloud how much more Will Rogers might have contributed to American life if he had lived:

Riding Into the Sunset was installed in 1942 but kept crated and not dedicated until 1947, when Margaret Truman, daughter of the president, sang “Home on the Range,” Rogers’s favorite song, and General Dwight David Eisenhower wondered aloud how much more Will Rogers might have contributed to American life if he had lived:

“What wisecrack would he have shot at us on a dozen differences in the United Nations; what kind of needling would he have used to awaken us to the relationships between maintenance of our liberties and a decent life for others that desire also to remain free? What quip would he have employed to shame us into greater saving of food for the needy; what shaft would he have launched to inspire us to greater cooperation at home? Could his wit, his insight, his homely phraseology make us better see that democracy has entered its decade of greatest crisis? Could he have helped make us see that personal ambitions and desires must now take second place to national need and solidarity?”

Lubbock, Dallas, and Claremore also have castings of Riding Into the Sunset. But the original stands, like the rest of Will Rogers Memorial Center, appropriately, on Amon Carter Square.