During the second half of the nineteenth century the American melting pot boiled over: The U.S. population increased by an average of thirty-three percent each decade.

In 1850 the U.S. population was twenty-three million. By 1880 it had more than doubled.

Much of that growth came from immigration.

Especially affected was New York City, which has been America’s biggest city since the first census in 1790. As a major seaport, New York City was transformed by immigration. The potato famine in Ireland had sent more than fifty thousand Irish to New York by 1847. That year more than fifty thousand Germans settled in the city. Those two groups alone increased the city’s population by one-third.

By 1853 almost half the population of the city was foreign born. The city’s population density was a claustrophobic fifty-six thousand per square mile. (For comparison, Fort Worth’s population density today is two thousand per square mile.)

New York City was home to the richest and poorest people in America: from Vanderbilts to vagrants. Among the poorest of the poor were immigrants who were forced into the worst jobs and the worst living conditions in the city: slums plagued with poverty, disease, crime.

The poor living conditions created a lot of orphans and a lot of neglected children—both native and foreign—who roamed the streets, slept in alleys, broke the law, went unschooled, unfed, and unsupervised.

In 1853 social reformer Charles Loring Brace (1826-1890; photo from Wikipedia) founded the New York Children’s Aid Society to help those children. Brace had a novel idea: Rather than warehouse these children in overcrowded, understaffed orphanages, why not send them to a new home, home on the range in the wide, open spaces of the American countryside, especially the romantic West?

In 1853 social reformer Charles Loring Brace (1826-1890; photo from Wikipedia) founded the New York Children’s Aid Society to help those children. Brace had a novel idea: Rather than warehouse these children in overcrowded, understaffed orphanages, why not send them to a new home, home on the range in the wide, open spaces of the American countryside, especially the romantic West?

“In every American community, especially in a western one, there are many spare places at the table of life,” Brace wrote. “They have enough for themselves and the stranger, too.”

For the immigrants among the needy children, a new life away from the evils of the big city would expose them to “the civilizing influences of American life.”

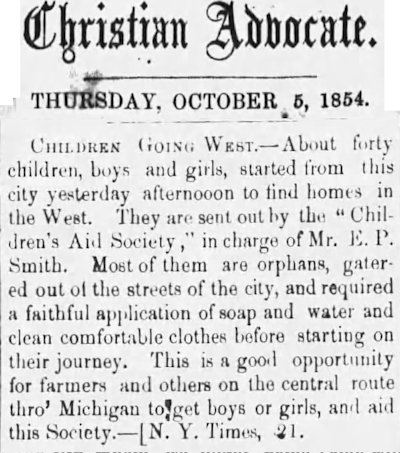

In 1854 the Children’s Aid Society began sending children—by train—to new homes. The first train went to Michigan.

In 1854 the Children’s Aid Society began sending children—by train—to new homes. The first train went to Michigan.

Every year thereafter the society sent children to new homes by train, at first to the Midwest and northern New York State and, after the Civil War, to southern and western states.

The Children’s Aid Society in its the first annual report said: “We have thus far sent off to homes in the country, or to places where they could earn an honest living, 164 boys and 43 girls, of whom some 20 were taken from prison, where they had been placed for being homeless on the streets. The great majority were the children of poor or degraded people, who were leaving them to grow up neglected in the streets. They were found by our visitors at the turning point of their lives, and sent to friendly homes, where they would be removed from the overwhelming temptations which poverty and neglect certainly occasion in a great city. Of these 200 boys and girls, a great proportion are so many vagrants or criminals saved; so much expense lessened to courts and prisons; so much poisonous influence removed from the city; and so many boys and girls, worthy of something better from society than a felon’s fate, placed where they can enter on manhood or womanhood somewhat as God intended that they should.”

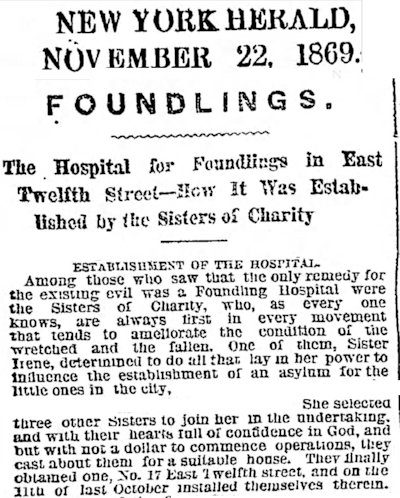

In 1869 the Sisters of Charity of New York City opened their Foundling Hospital. On the hospital’s first day of operation the sisters placed a wicker crib just inside the front door of the hospital to receive unwanted children and children whose parents could not care for them. The sisters found a baby in the crib on the second morning. In the next month forty-five more babies followed. By 1914 sixty thousand babies would be placed in that crib.

In 1869 the Sisters of Charity of New York City opened their Foundling Hospital. On the hospital’s first day of operation the sisters placed a wicker crib just inside the front door of the hospital to receive unwanted children and children whose parents could not care for them. The sisters found a baby in the crib on the second morning. In the next month forty-five more babies followed. By 1914 sixty thousand babies would be placed in that crib.

In 1875 the Foundling Hospital, like the New York Children’s Aid Society, began sending needy children across America on trains. The Sisters of Charity sent children to Catholic couples. Local parish priests vetted parishioners seeking to adopt. By the time the sisters’ trains stopped rolling in 1919, the hospital was placing one thousand children a year.

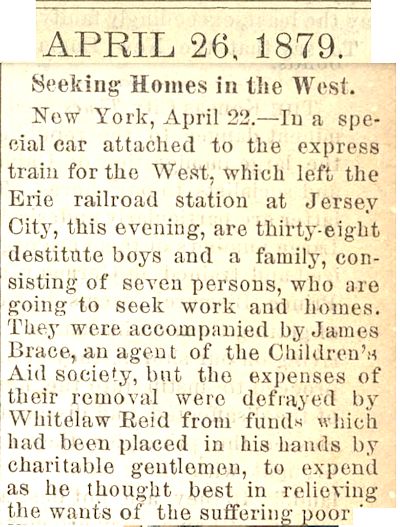

By 1879 the Fort Worth Democrat took note of the westward-bound trains of children.

By 1879 the Fort Worth Democrat took note of the westward-bound trains of children.

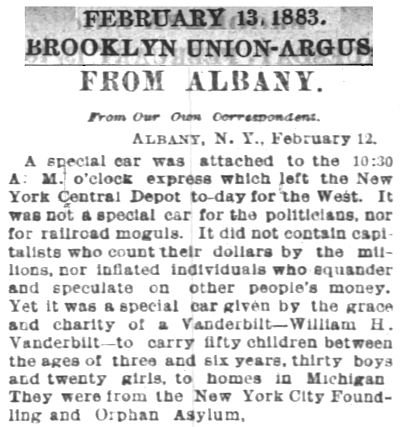

In 1883 the Foundling Hospital shipped children to Michigan in a car donated by William H. Vanderbilt.

In 1883 the Foundling Hospital shipped children to Michigan in a car donated by William H. Vanderbilt.

The 1880s brought a new wave of immigration to New York City as shiploads of Europeans arrived at Ellis Island in New York Harbor.

This new wave of immigrants came to America to find jobs or to escape religious persecution or war. European Jews, Italians, Russians, and Greeks settled in ethnic neighborhoods of New York City.

Beginning in 1886 the first sight of America for many of “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” was the new Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor.

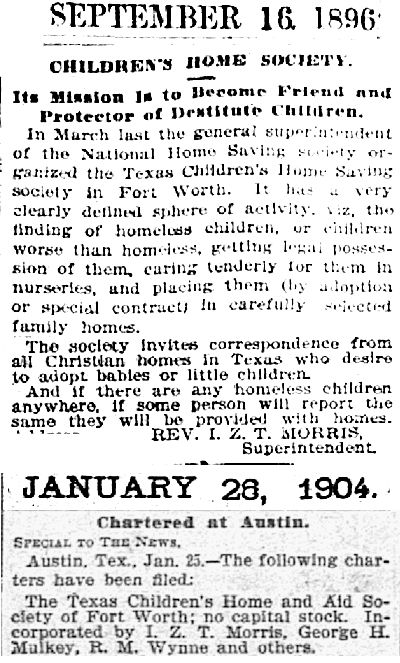

Fast-forward one year and fifteen hundred miles. According to the Star-Telegram, in 1887 Fort Worth’s first orphan train arrived. It was met by Reverend Isaac Zachary Taylor Morris and his wife Belle.

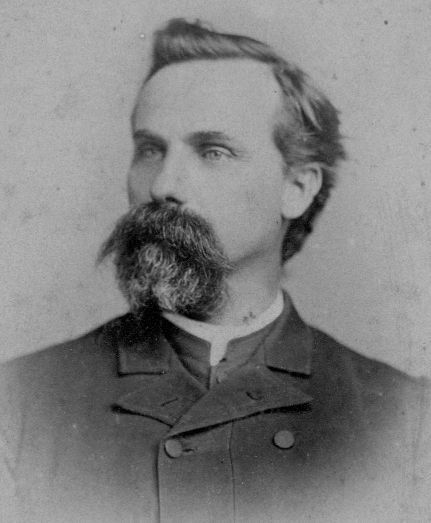

Morris was born in Georgia in 1847. He enlisted in the Confederate Army at age fourteen, was wounded, taken prisoner of war. After the war he graduated from Auburn University and became a Methodist preacher first in Alabama and then Arkansas. In 1875 he was transferred to Houston. (Photo from the Central Texas Conference United Methodist Church.)

Morris was born in Georgia in 1847. He enlisted in the Confederate Army at age fourteen, was wounded, taken prisoner of war. After the war he graduated from Auburn University and became a Methodist preacher first in Alabama and then Arkansas. In 1875 he was transferred to Houston. (Photo from the Central Texas Conference United Methodist Church.)

He moved to Fort Worth about 1880, the Star-Telegram said, and continued his ministerial work.

When that first orphan train arrived in Fort Worth in 1887, not all the children on board were claimed by prearranged adoptive parents. Morris and his wife Belle took in the unclaimed children to find homes for them.

From that first train, the Morrises continued to help orphan train children and others, hosting as many as fourteen children at a time in their own home. Their informal work with orphans evolved into a formal organization: the Texas Children’s Home and Aid Society. It was organized in 1896 and chartered in 1904. Morris was superintendent.

In 1906 the Texas Children’s Home and Aid Society bought a house on Avenue H in Poly to accommodate children until they were placed into homes.

In 1906 the Texas Children’s Home and Aid Society bought a house on Avenue H in Poly to accommodate children until they were placed into homes.

Morris was a reformer. He advocated providing a pension for single mothers, opposed placing children with couples who already had biological children, fearing that the adopted children would be viewed as little more than servants. He opposed the incarceration of children with adults and advocated criminalizing the desertion of families by fathers.

And by 1906 Morris even had changed his view of the orphan trains, saying, “We want the legislature to pass a bill to prevent the importation of children into our state by the carload. This only increases the number of our paupers and does not add to our desirable citizenship.”

Another reformer, Edna Gladney, joined the board of Texas Children’s Home and Aid Society in 1910.

That was the year this photo of I. Z. T. Morris and two children of the home was taken. The Morrises’ connection with some children would continue into the children’s college years. (Photo from the Central Texas Conference United Methodist Church.)

That was the year this photo of I. Z. T. Morris and two children of the home was taken. The Morrises’ connection with some children would continue into the children’s college years. (Photo from the Central Texas Conference United Methodist Church.)

Reverend Morris died in 1914 in the house that was his home and the home of his orphans. He had found homes for one thousand children.

Morris is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Morris is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Upon his death his widow, Belle, became superintendent of the society and served until her death in 1924. Edna Gladney was named superintendent in 1927.

In 1950 Texas Children’s Home and Aid Society, which had evolved out of that first orphan train in 1887, was renamed the “Edna Gladney Home.”

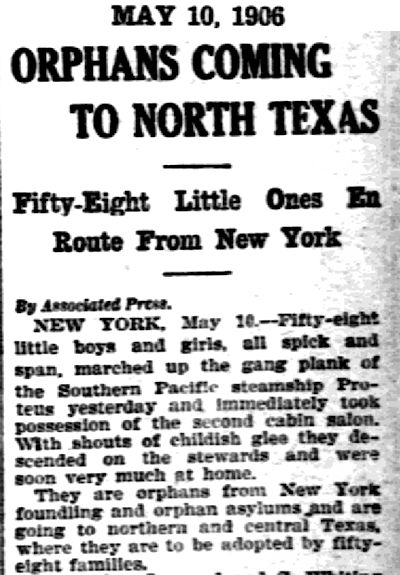

Even though Texas received an estimated five thousand orphans by train over the years, the trains did not receive much newspaper coverage at the time. And they weren’t called “orphan trains” at the time. In fact, the orphans didn’t always travel by train, at least on the first leg of their journey. In 1906 fifty-eight “spick and span” orphans bound for northern and central Texas sailed by steamship, probably to Galveston.

Even though Texas received an estimated five thousand orphans by train over the years, the trains did not receive much newspaper coverage at the time. And they weren’t called “orphan trains” at the time. In fact, the orphans didn’t always travel by train, at least on the first leg of their journey. In 1906 fifty-eight “spick and span” orphans bound for northern and central Texas sailed by steamship, probably to Galveston.

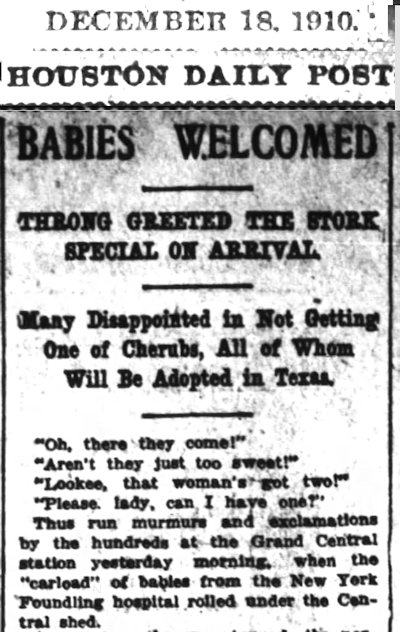

A “stork special” arrived in Houston in 1910.

A “stork special” arrived in Houston in 1910.

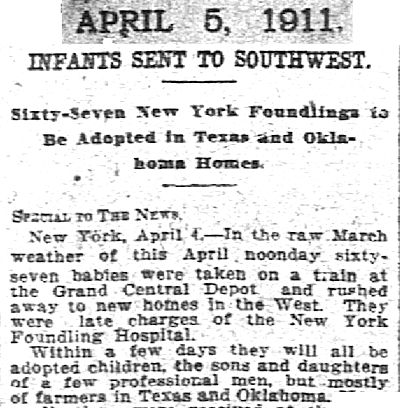

In 1911 sixty-seven children left the Foundling Hospital, most of them bound for farmers in Texas and Oklahoma.

In 1911 sixty-seven children left the Foundling Hospital, most of them bound for farmers in Texas and Oklahoma.

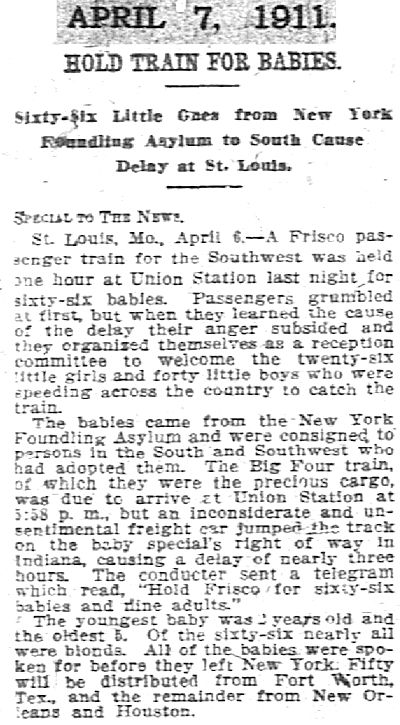

Two days later the Dallas Morning News reported that the train would stop in Fort Worth, where fifty of the children would be “distributed.”

Two days later the Dallas Morning News reported that the train would stop in Fort Worth, where fifty of the children would be “distributed.”

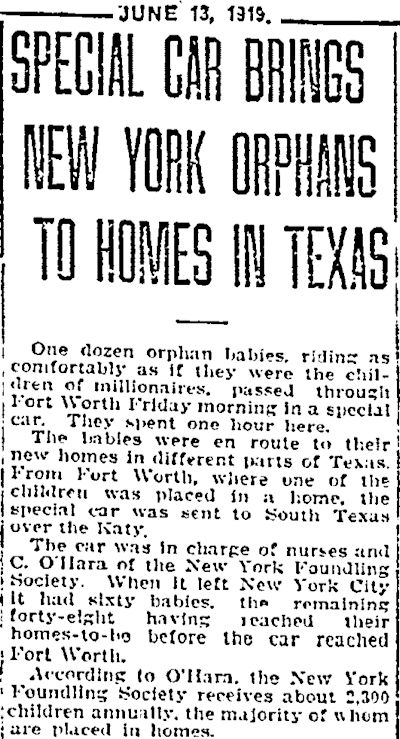

In 1919 the Star-Telegram reported that by the time a train of sixty children reached Fort Worth on its way to south Texas, forty-eight of the children had reached their “homes-to-be.” One child remained in Fort Worth.

In 1919 the Star-Telegram reported that by the time a train of sixty children reached Fort Worth on its way to south Texas, forty-eight of the children had reached their “homes-to-be.” One child remained in Fort Worth.

Reverend Morris, of course, was not the only reformer who came to see flaws in the orphan train system, noble though its intent was.

Some critics said the system targeted foreign-born children, depriving them of their ethnic enclaves in the big city in order to assimilate them in America’s heartland.

Other critics said the New York Children’s Aid Society targeted Catholic children, sending them to rural areas—which were largely Protestant—in hopes they would be converted.

Still other critics said the system was abused by farmers who viewed the system as a way to acquire young, strong farm workers.

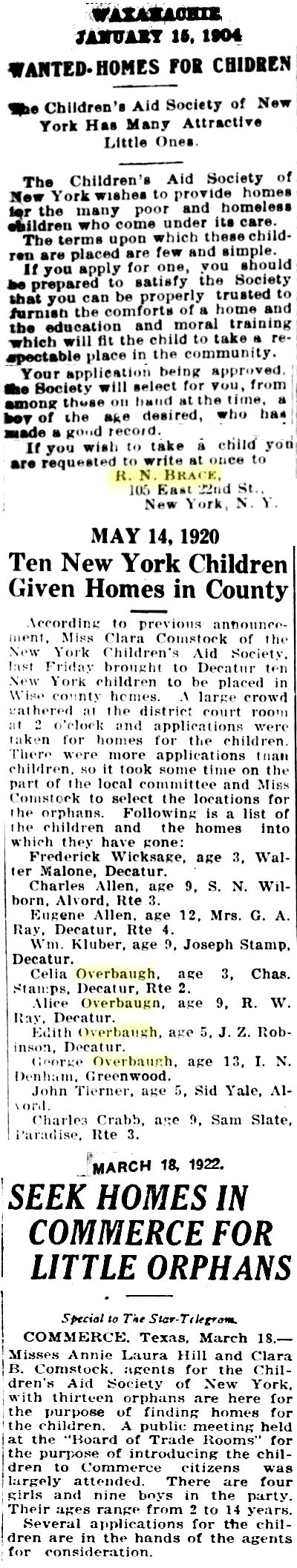

The system was criticized for being impersonal. In the Waxahachie ad above, note that people desiring to adopt a child could apply in writing to the Children’s Aid Society, which would “select for you, from among those on hand at the time, a boy of the age desired” and ship him out on a train. (R. N. Brace surely was a relative of Charles Loring Brace.)

The system was criticized for separating siblings along the train route. In the Decatur news story note that the four Overbaugh siblings went to four different homes.

Critics said the system was demeaning to the children. The Commerce news story shows that not all of the children on a train had a prearranged couple to meet them at a station. In some towns the children were marched onto the station platform or to a nearby school or church or other public building, where they were lined up so that adults could select them like pets at an animal shelter. Some children, desperate to be adopted, performed for the crowd. One girl recited the names of all the presidents of the United States. Others told jokes or danced.

The system was criticized for breaking up homes, sending children into abusive households, and depriving the children of information about their past—birth families, ethnic identities, religious heritage—making it difficult for the children later to reconstruct their early lives and reconnect with relatives.

Gradually the orphan trains fell out of favor. Just as Fort Worth’s Reverend Morris had advocated in 1906, some states did pass laws prohibiting the orphan trains. State and municipal governments increased their social services for needy children. After the federal government enacted child welfare reforms, in 1929 the orphan trains—one of the most controversial social experiments in American history—came to the end of the line. The trains had transported about two hundred thousand children.

In the 1970s and 1980s the orphan trains began to receive national attention as films and books were produced, support organizations were formed, reunions were held, and the surviving orphan train riders were interviewed by the media.

One orphan train rider, George Meason of Odessa, was seventy-four when he was interviewed. He recalled that he and his brother Julius were supposed to be adopted by a preacher in Whitewright. But when the preacher saw that Julius was “sickly,” he took only George. Julius continued on the train to be adopted in a later town.

For years Meason tried to find out anything he could about his mother, whom he did not remember. Eventually he obtained her death certificate. She had died in 1929. Fifty-three years later he visited her grave in New York and bought a marker for it.

“It was like a magnet drawing me to the cemetery,” he recalled. “I cried from the time we were thirty miles away. You still have a craving to know, and a lot of love in your heart for your mother and daddy.”

Lee Nailling of Atlanta, Texas was seventy-seven when he was interviewed. In 1926 Nailling was nine his mother died. His father was out of work and, unable to feed his seven children, took three of his sons to the Children’s Aid Society. Lee and brothers Leo, six, and Gerald, two, boarded a train headed for Texas with forty other children.

Nailling remembered his father coming to the train station when he and his brothers left for Texas. His father cried.

“I guess because I was the oldest, he [his father] gave me a pink envelope with his return address on it,” Nailling recalled. Nailling remembered choking back tears as he boarded the train.

When he got ready to sleep on his first night on the train, he tucked his father’s envelope into his coat pocket for safekeeping and fell asleep. The next morning the envelope was gone. While he was searching for it, an agent who accompanied the children told him: “You won’t need that where you’re going.”

Nailling recalled, “We would stop in towns, and they would examine us, feel our muscles and question us. It’s like you take a cow to a sale barn. Some man grabbed ahold of my cheeks and ran his hand through my mouth. It made you bitter. I had no respect for anybody who come up to me to feel my muscles.”

“There really wasn’t much love,” he said. “We wore numbers, sort of like putting a number on a cow at an auction.”

“We’d see others [siblings] being separated. I was so scared that was going to happen to us,” he recalled.

His fear came true when only Gerald, the youngest, was taken by a Clarksville couple. Nailling remembered how happy the little boy was from all the attention—until he looked back at his brothers and started to cry.

Nailling and his other brother were later taken by a couple with nine children. But Nailling was removed from the household because the couple couldn’t afford both boys. After one more brief stay with a family, he went to live with Ben and Ollie Nailling, who adopted him.

“I always wondered all my life about my family,” Nailling said.

Marion Strittmatter of Fort Worth was seventy-two when she was interviewed.

Mrs. Strittmatter was three years old when she rode the train west in 1925 from New York City.

“The only thing I know about my mother is that she took me to the Foundling Hospital. She was twenty-four. She gave a religious preference, and that was all. There was never a reason why,” Mrs. Strittmatter said.

Like so many orphan train riders, Mrs. Strittmatter spent a lifetime wondering why her mother gave her up.

“I have always kind of thought she must have had a reason. I thought it was something serious. What really held me together is that I had her name. I was named after her, and I always thought my mother loved me.”

Still, Strittmatter was one of the fortunate children. She said she went to a good home with “unselfish parents,” although they had chosen her “just like a dress out of J.C. Penney’s [catalog].”

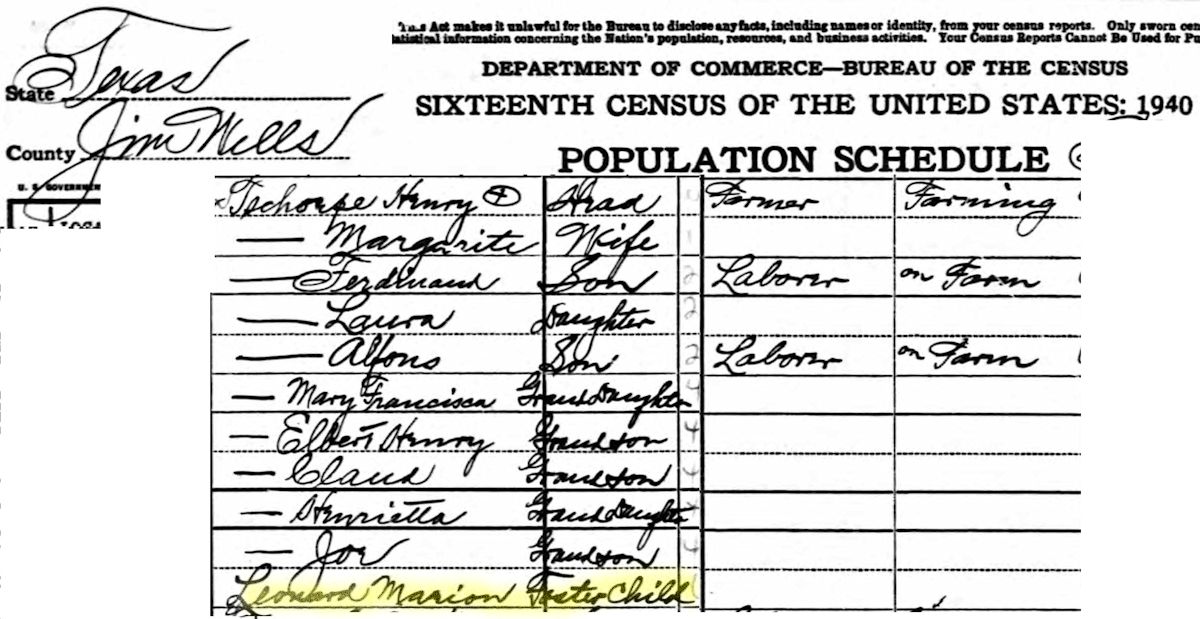

When Strittmatter arrived in Jim Wells County the Tschoepe family met the train and took her to the family farm. The family had twelve children. The Tschoepes encouraged her to retain her original name, Marion Leonard, in case her relatives ever tried to find her. When she turned eighteen Mrs. Strittmatter tried to find her mother. She tried again when she was sixty-eight. She never learned any more than her mother’s name and age.

When Strittmatter arrived in Jim Wells County the Tschoepe family met the train and took her to the family farm. The family had twelve children. The Tschoepes encouraged her to retain her original name, Marion Leonard, in case her relatives ever tried to find her. When she turned eighteen Mrs. Strittmatter tried to find her mother. She tried again when she was sixty-eight. She never learned any more than her mother’s name and age.

Of the Tschoepes Mrs. Strittmatter said, “They were good to me.”

“They taught me how to love, and they taught me how to work hard and get along with other people. When I had my own family, it wasn’t such a chore.”

Marion Strittmatter, one of the last riders of the orphan trains, died in 2006. She was the mother of ten children, one of them adopted. (Photos from Find a Grave.)

Other Cowtown benefactors of children:

Lena Pope

Edna Gladney

Belle Burchill

Masonic Home

Berachah Industrial Home for the Redemption of Erring Girls

Thanks for the book titles, Mike. I found your story uplifting to a point that there was some slim chance of a better life than the condition of children abandoned and abused on the squalid, dangerous streets of New York. But I’m no Pollyanna given the grim future many of those kids faced when they were put aboard those trains.

It’s a situation unbound by time or place. Many children born into poverty have few options-none of them good. Bless those people who try to give such children the lesser of x evils.

Wonderful uplifting yet sad, poignant story that I’ve read bit and pieces about here and there. I’m going to try to find a good book on the orphan trains, preferably one that focuses on the orphans and their lives from personal interviews like you’ve done in this intriguing article. I should be able to find one, but do you known of any? Thanks.

Jim, you are a glutton for punishment. But seriously, you are right to focus on the “uplifting” rather than the “sad” of this human saga. Be aware that several orphan train books, such as Orphan Train by Kline, are historical fiction, although they may well reflect the truth of the subject. Other books, such as We Rode the Orphan Trains by Warren and The Orphan Trains: Placing Out in America by Holt, are nonfiction.

This was a well-intentioned effort with so many sad side stories. Often the children were stripped of any personal belongings that linked them with their original family members: photos, letters, toys, mementos, etc.

There is an Orphan Train Museum in Concordia KS that is well worth a visit.