OK, everybody, intermission is over. Got your popcorn and soda pop from the lobby? Great. Let’s get back to our seats and resume our survey of a century of cinema in Fort Worth (see Part 1).

1947

The decade between 1937 and 1947 brought a profusion of new neighborhood theaters to town: River Oaks, Tower, Gateway, Bowie, Varsity, White (which would become the Berry Theater), TCU, and Haltom.

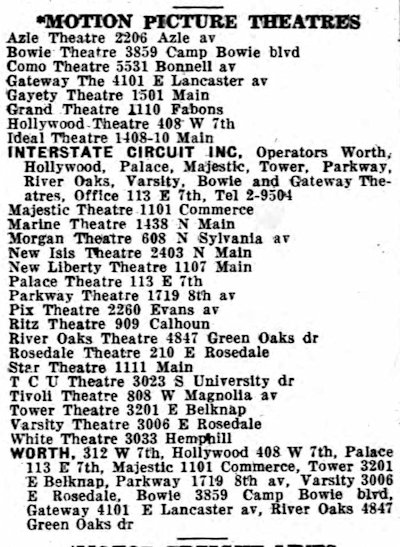

By 1947 the big four downtown theaters—Majestic, Palace, Worth, Hollywood—and the Parkway, Varsity, Bowie, Gateway, Tower, and River Oaks were part of the mighty Interstate theater chain.

Note that if you didn’t want to watch Laurel and Hardy, Tyrone Power, or Henry Fonda on the screen, you could go out to North Side Coliseum and watch “Ma” Bogash and her circle of friends.

The 1947 city directory listed additional neighborhood theaters: Azle, Como, Grand, Morgan, Pix, and Rosedale.

The 1947 city directory listed additional neighborhood theaters: Azle, Como, Grand, Morgan, Pix, and Rosedale.

In 1948 the Interstate chain opened a new “suburban” theater: the 7th Street.

In 1948 the Interstate chain opened a new “suburban” theater: the 7th Street.

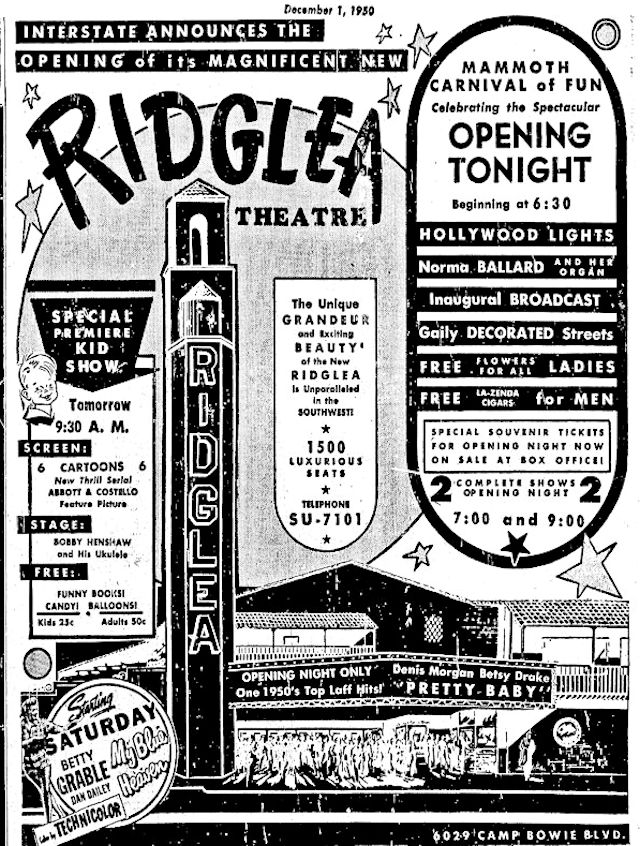

Two years later a superlative-laden splash in the Star-Telegram trumpeted the opening of yet another Interstate theater, the Ridglea, on December 1, 1950 with free flowers for women and free cigars for men. (Note the SUnset phone exchange. In 1956 SUnset numbers became PErshing 8- numbers as Fort Worth phone numbers changed from six to seven digits to accommodate long-distance dialing.)

Two years later a superlative-laden splash in the Star-Telegram trumpeted the opening of yet another Interstate theater, the Ridglea, on December 1, 1950 with free flowers for women and free cigars for men. (Note the SUnset phone exchange. In 1956 SUnset numbers became PErshing 8- numbers as Fort Worth phone numbers changed from six to seven digits to accommodate long-distance dialing.)

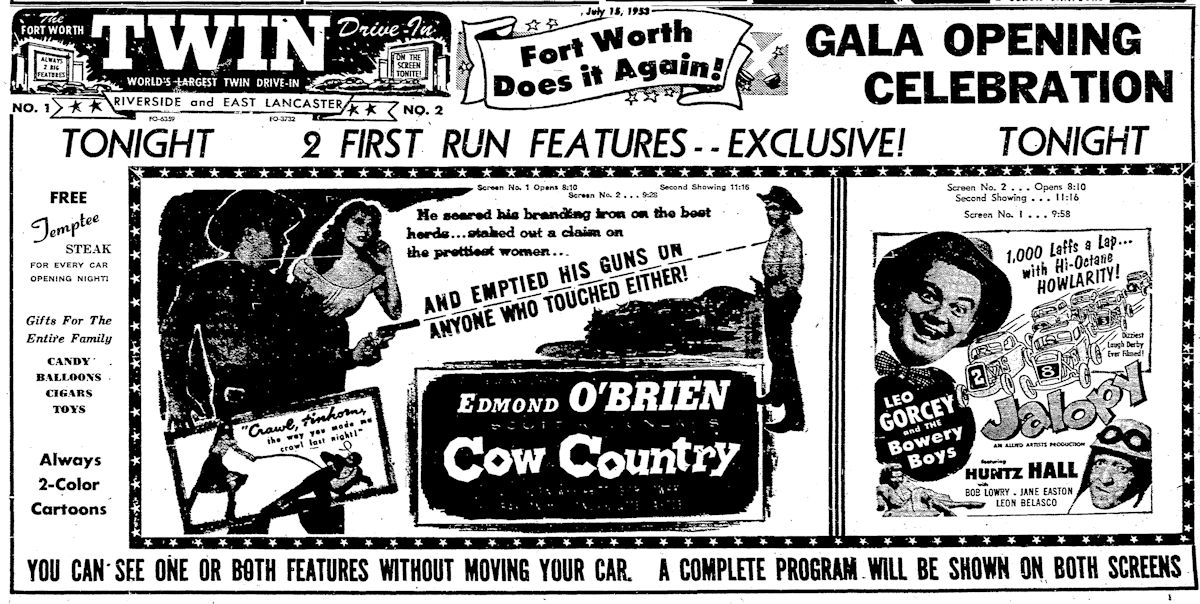

In 1953 Fort Worth gave birth to twins: The city’s first two-screen drive-in theater opened on Riverside Drive at East Lancaster Avenue.

In 1953 Fort Worth gave birth to twins: The city’s first two-screen drive-in theater opened on Riverside Drive at East Lancaster Avenue.

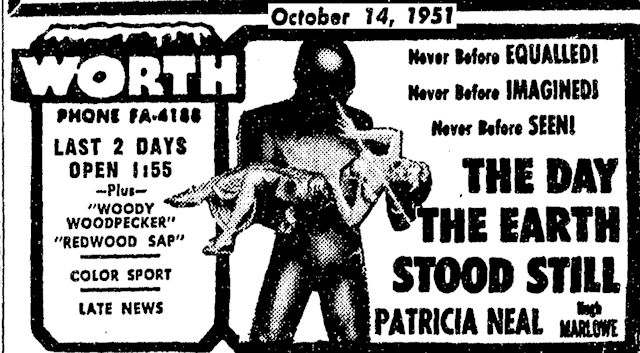

The 1950s were Hollywood’s golden age of sci-fi and horror as movies brought us everything from A to Z (aliens to zombies). The decade began auspiciously with the thought-provoking and understated The Day the Earth Stood Still in 1951.

The 1950s were Hollywood’s golden age of sci-fi and horror as movies brought us everything from A to Z (aliens to zombies). The decade began auspiciously with the thought-provoking and understated The Day the Earth Stood Still in 1951.

Two years later Vincent Price, Frank Lovejoy, and Carolyn Jones appeared in person at the Worth Theater for the premiere of House of Wax in 3D.

Two years later Vincent Price, Frank Lovejoy, and Carolyn Jones appeared in person at the Worth Theater for the premiere of House of Wax in 3D.

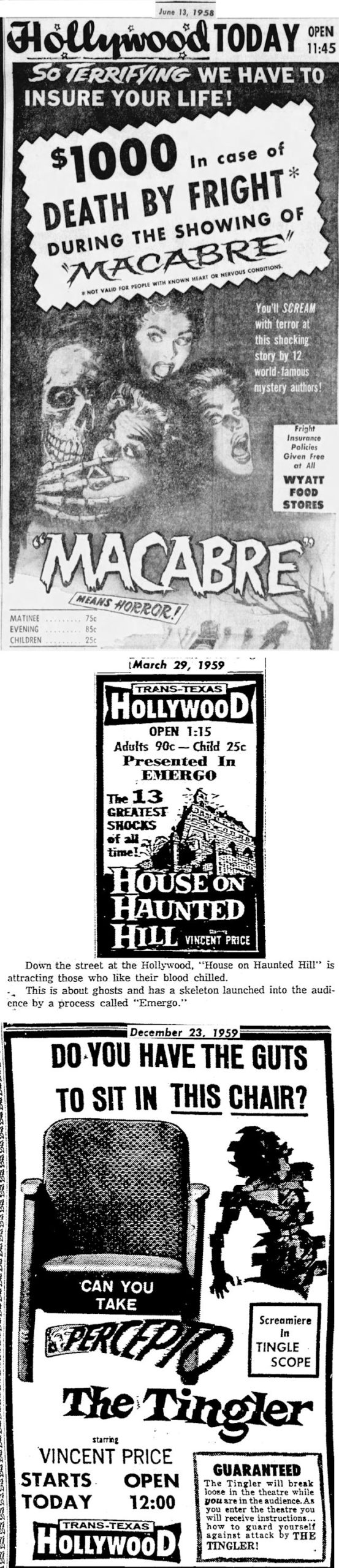

By the late 1950s we were being entertained by the gimmickry of producer-director William Castle.

By the late 1950s we were being entertained by the gimmickry of producer-director William Castle.

Castle knew how to put people in theater seats. And then he jolted them with buzzers, strafed them with flying skeletons, and offered them free life insurance policies.

Ads for his Macabre in 1958 offered $1,000 to any theater patron who died of fright while watching the movie. “Fright insurance policies” were available free at all Wyatt food stores. “Not valid for people with known heart or nervous conditions.”

To prevent breaking the tension in the theater during the movie’s climax, late-arriving patrons were not seated “during the last 10 minutes of Macabre.”

The next year was a Castle twofer: The Tingler and House on Haunted Hill.

House on Haunted Hill showings featured another Castle gimmick: Emergo, a pulley system that “flew” a plastic skeleton over the theater audience late in the film.

Ad copy for The Tingler was tongue-in-shriek: “Screamiere in Tingle Scope” “The Tingler will break loose in the theatre while you are in the audience. As you enter the theatre you will receive instructions . . . how to guard yourself against attack by THE TINGLER.”

Percepto was a system of vibrating devices that were attached under theater chairs and activated to tingle at an appropriate moment during the onscreen action.

The movie industry is a master of public relations. And Fort Worth, as a city with three newspapers and several theaters, was often part of Hollywood PR campaigns.

The movie industry is a master of public relations. And Fort Worth, as a city with three newspapers and several theaters, was often part of Hollywood PR campaigns.

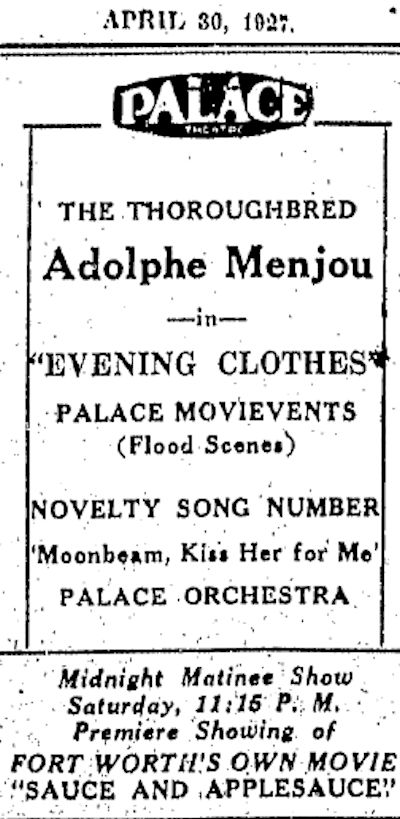

For example, in 1927 Publix, the chain that owned the Palace Theater, and the Fort Worth Press collaborated to produce an all-Fort Worth movie: Sauce and Applesauce. The movie was written by and cast with Fort Worth residents.

Just months later the Worth Theater—another Publix theater—and the Star-Telegram produced another all-Fort Worth movie: Beauty and Brains.

In 1948 RKO studio, to promote its film Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, built replicas of the movie’s dream house in major cities, including Fort Worth. Fort Worth’s dream house was—and is—located at 3801 Arundel Avenue in the Westcliff West neighborhood. The house was built by a local contractor. General Electric supplied the appliances. The house was fully furnished and decorated by local companies. The public was given tours of the house.

In 1948 RKO studio, to promote its film Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, built replicas of the movie’s dream house in major cities, including Fort Worth. Fort Worth’s dream house was—and is—located at 3801 Arundel Avenue in the Westcliff West neighborhood. The house was built by a local contractor. General Electric supplied the appliances. The house was fully furnished and decorated by local companies. The public was given tours of the house.

Ten years later Paramount studio invited newspaper entertainment columnists from around the country to appear in small roles in the journalism-themed movie Teacher’s Pet. So, Jack Gordon of the Press went to Hollywood.

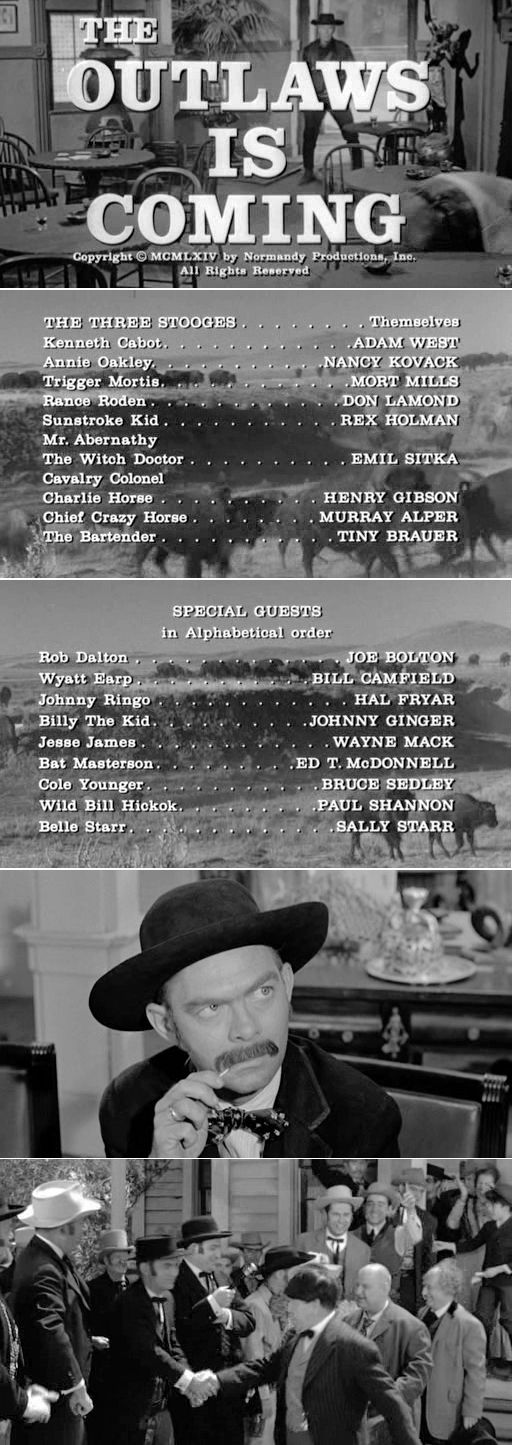

In 1965 Bill Camfield of Channel 11’s Slam Bang Theater was among the hosts of children’s shows around the country who were given roles in the movie The Outlaws Is Coming. Camfield portrayed Wyatt Earp.

In 1965 Bill Camfield of Channel 11’s Slam Bang Theater was among the hosts of children’s shows around the country who were given roles in the movie The Outlaws Is Coming. Camfield portrayed Wyatt Earp.

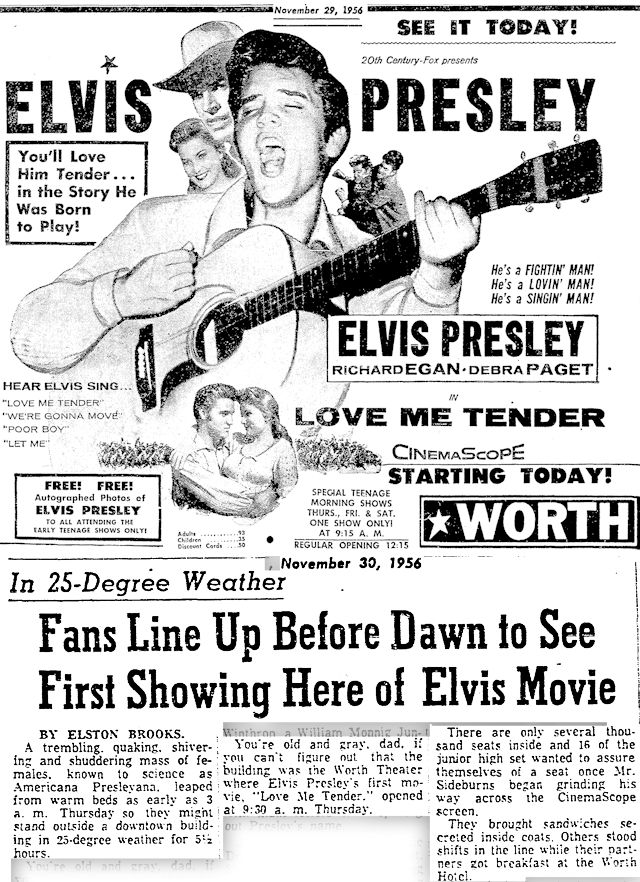

On November 29, 1956 some memories were made at the Worth Theater when hundreds of teenagers—overwhelmingly female—began arriving at 4:30 a.m. in subfreezing weather to see a 9:15 a.m. “special teenage morning show” of Elvis Presley’s first movie, Love Me Tender.

On November 29, 1956 some memories were made at the Worth Theater when hundreds of teenagers—overwhelmingly female—began arriving at 4:30 a.m. in subfreezing weather to see a 9:15 a.m. “special teenage morning show” of Elvis Presley’s first movie, Love Me Tender.

1957

By 1957 motion pictures had been competing with television for almost ten years, but theaters proliferated in Fort Worth. There were more neighborhood theaters. And more drive-in theaters: twelve.

By 1957 motion pictures had been competing with television for almost ten years, but theaters proliferated in Fort Worth. There were more neighborhood theaters. And more drive-in theaters: twelve.

Note the ads for the Italian Inn and the Skyliner Ballroom, a remnant of the era of bright lights and dark deeds along Jacksboro Highway.

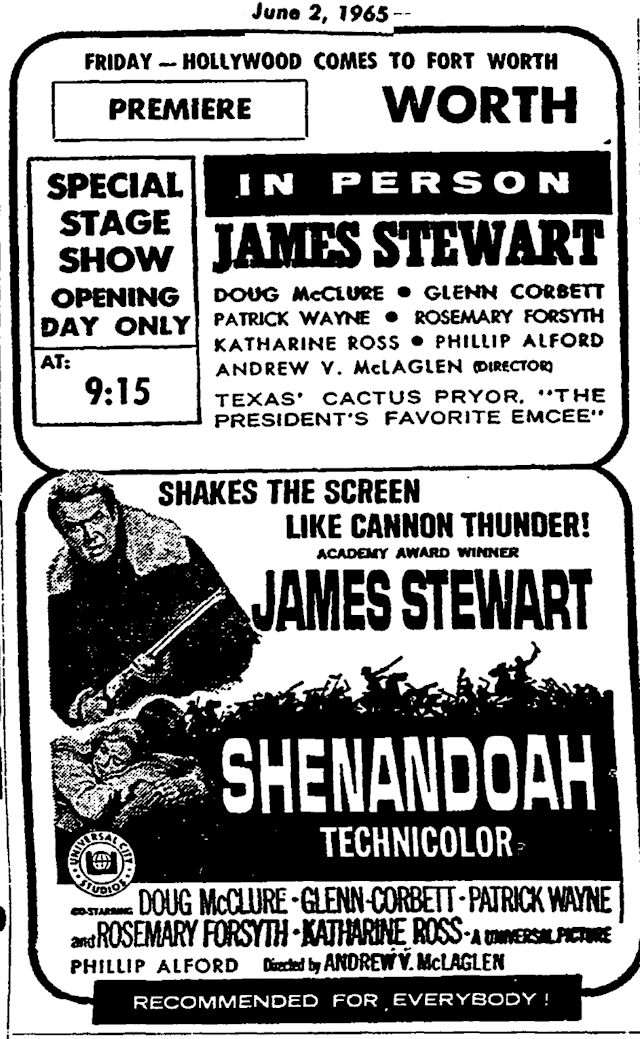

The Hollywood Theater, as part of the Interstate chain, may have hosted most of the galas, but the Worth Theater hosted its share. In 1965 James Stewart led the cast of Shenandoah in a personal appearance at the Worth. Other stars who appeared at the Worth Theater to promote their new movies included Abbott and Costello, Gary Cooper, Gregory Peck, and John Wayne.

The Hollywood Theater, as part of the Interstate chain, may have hosted most of the galas, but the Worth Theater hosted its share. In 1965 James Stewart led the cast of Shenandoah in a personal appearance at the Worth. Other stars who appeared at the Worth Theater to promote their new movies included Abbott and Costello, Gary Cooper, Gregory Peck, and John Wayne.

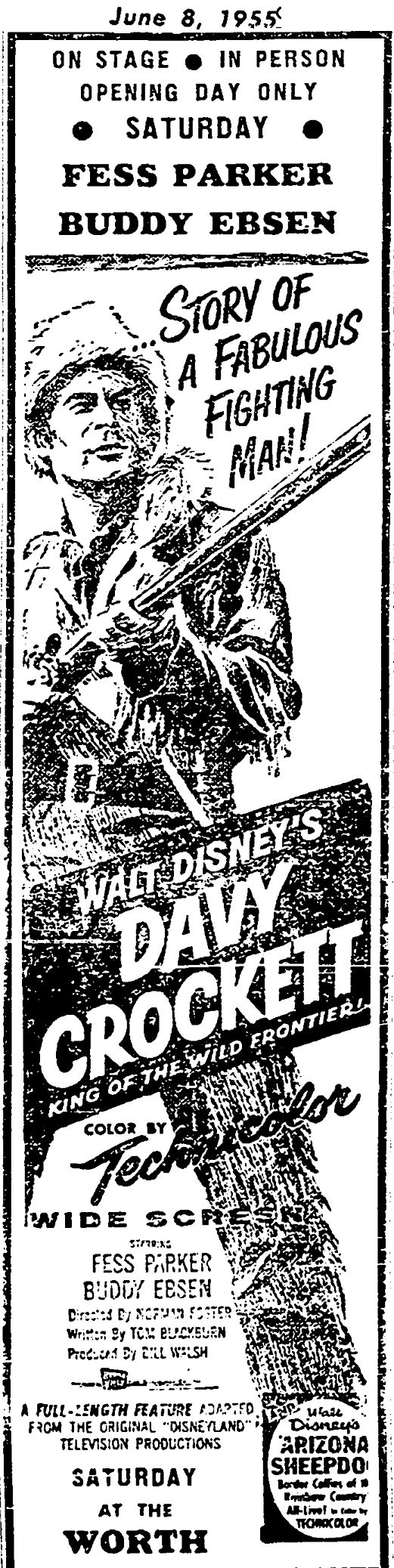

And, of course, Cowtown-born Fess Parker.

And, of course, Cowtown-born Fess Parker.

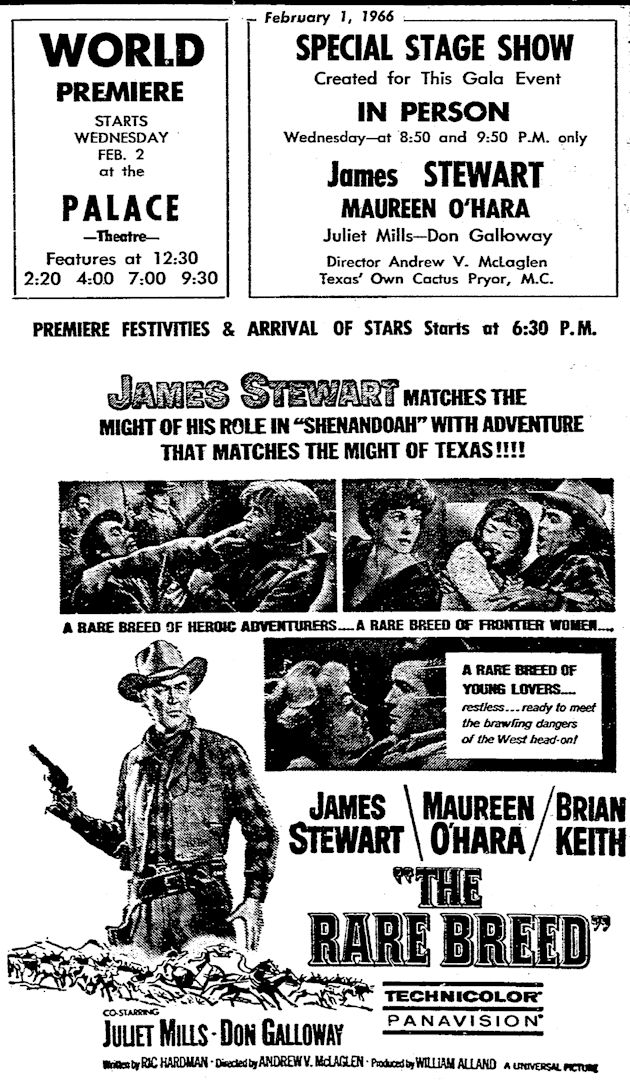

At the Palace, in 1966 James Stewart and Maureen O’Hara appeared to promote The Rare Breed.

At the Palace, in 1966 James Stewart and Maureen O’Hara appeared to promote The Rare Breed.

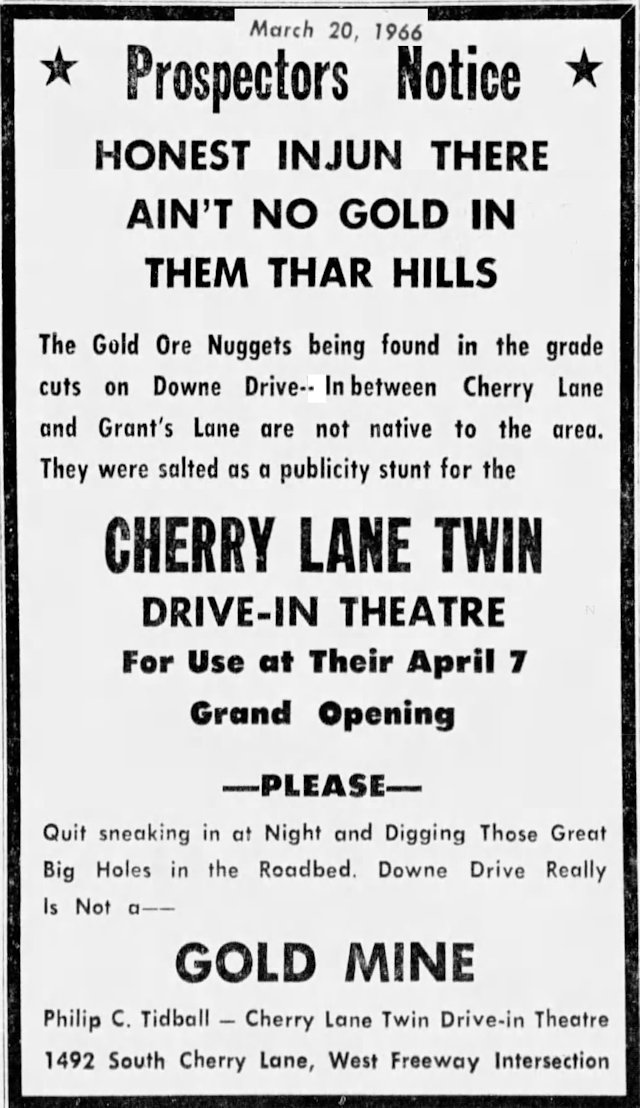

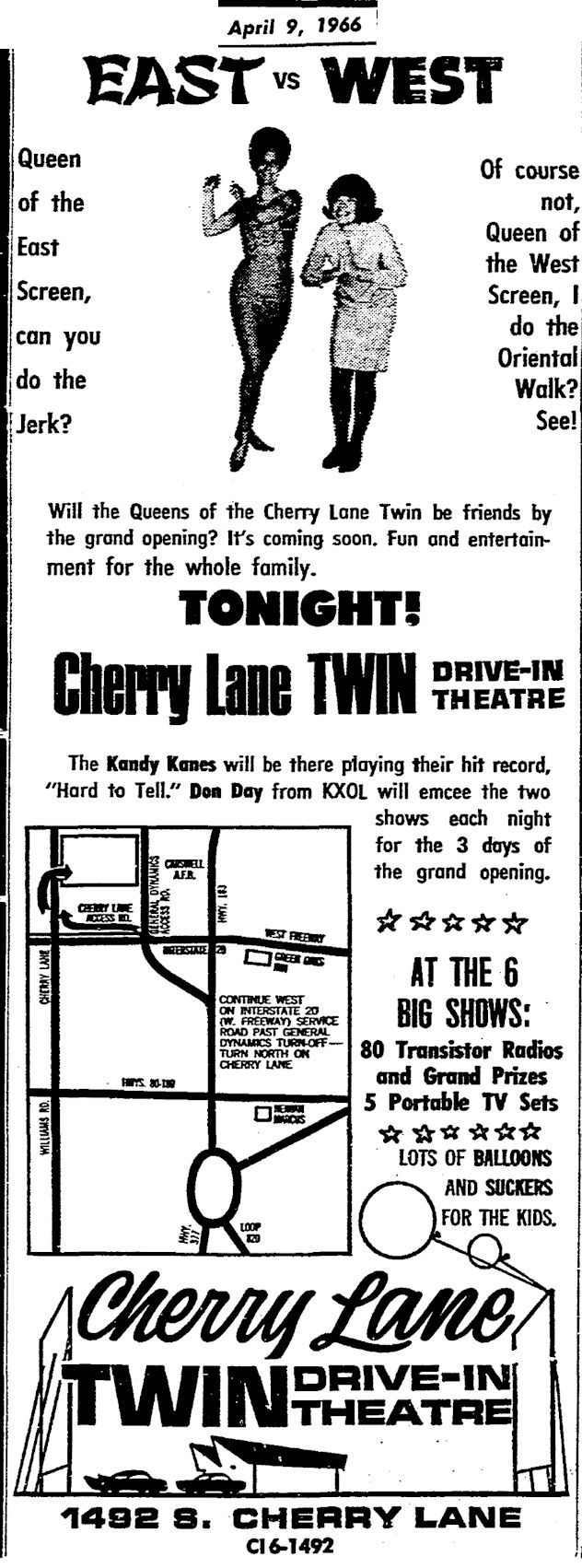

Also in 1966 Fort Worth gave birth to its second set of twins when the Cherry Lane drive-in theater opened.

Also in 1966 Fort Worth gave birth to its second set of twins when the Cherry Lane drive-in theater opened.

1967

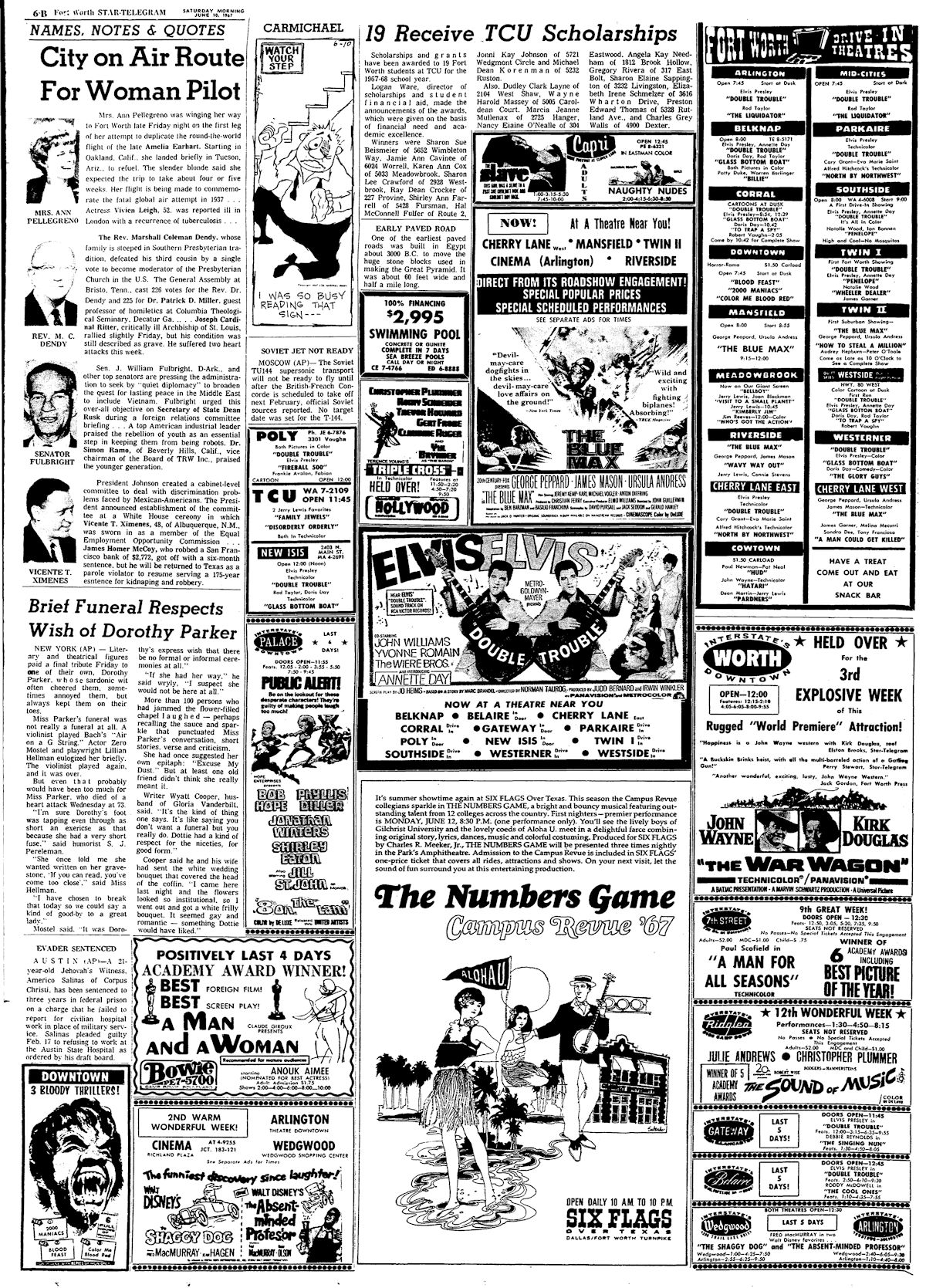

By 1967 local theaters had been competing with Six Flags Over Texas since 1961.

By 1967 local theaters had been competing with Six Flags Over Texas since 1961.

On the screen, established stars like John Wayne and Kirk Douglas had been competing with Elvis Presley since 1956.

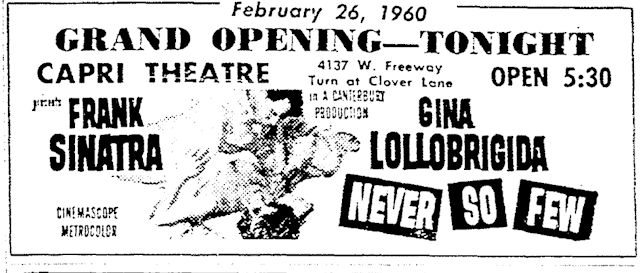

And by 1967 mainstream films were competing with films that allocated a very small budget for wardrobe: The Capri theater on the West Side was showing films such as Naughty Nudes.

The Capri had opened in 1960 as a mainstream theater but by 1961 had become “the art film theatre.”

The Capri had opened in 1960 as a mainstream theater but by 1961 had become “the art film theatre.”

The decade between 1957 and 1967 was the golden age of drive-in theaters. There were more than four thousand across the nation.

The decade between 1957 and 1967 was the golden age of drive-in theaters. There were more than four thousand across the nation.

In 1957 Fort Worth had twelve drive-ins theaters. By 1967 it had fifteen, two of them with twin screens.

But the 1973 oil crisis, with resultant higher gasoline prices and daylight saving time, hurt drive-ins. So did multiplex theaters (see below) and the increasing popularity of television. Also, drive-in theaters occupied large tracts of land—land that often was more valuable than the revenue the theaters generated.

To survive, drive-in theaters lowered their ticket prices and turned to genres such as low-budget films, R-rated and X-rated films, and Spanish-language films for a limited viewership.

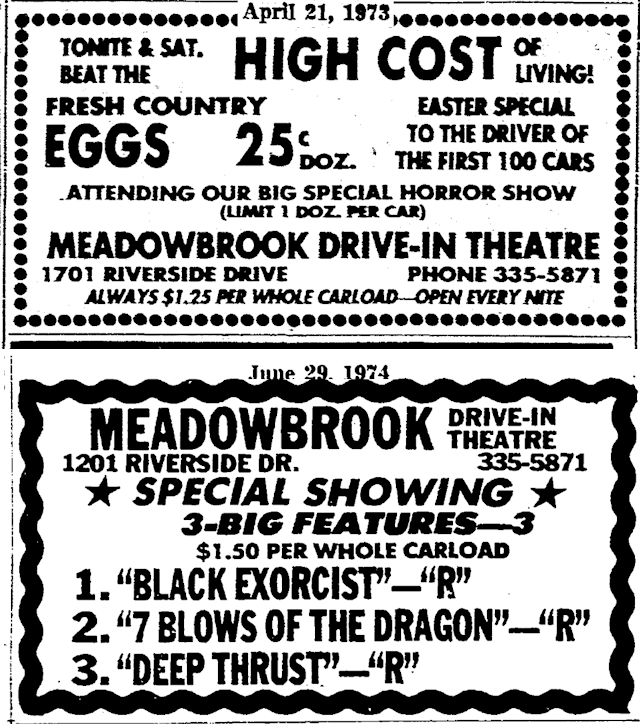

For example, in 1973 the Meadowbrook drive-in theater was showing low-budget horror films, charging $1.25 ($6 today) a carload, and selling “fresh country eggs” for twenty-five cents a dozen.

For example, in 1973 the Meadowbrook drive-in theater was showing low-budget horror films, charging $1.25 ($6 today) a carload, and selling “fresh country eggs” for twenty-five cents a dozen.

By 1974 the Meadowbrook was showing R-rated movies.

By 1977 Fort Worth would have only six drive-in theaters.

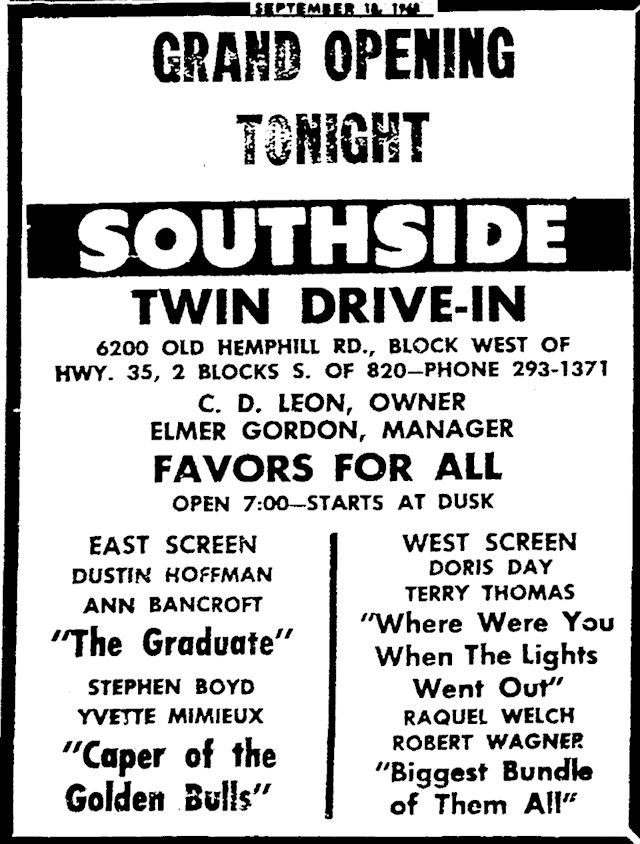

In 1968 Fort Worth got its third set of twins as the Southside Twin opened on Old Hemphill Road.

In 1968 Fort Worth got its third set of twins as the Southside Twin opened on Old Hemphill Road.

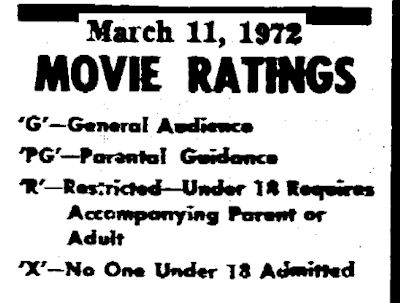

Also in 1968 the motion picture industry replaced the 1934 Hays Code with the Motion Picture Association (MPA) film rating system to rate each film’s suitability for audiences based on its content.

Also in 1968 the motion picture industry replaced the 1934 Hays Code with the Motion Picture Association (MPA) film rating system to rate each film’s suitability for audiences based on its content.

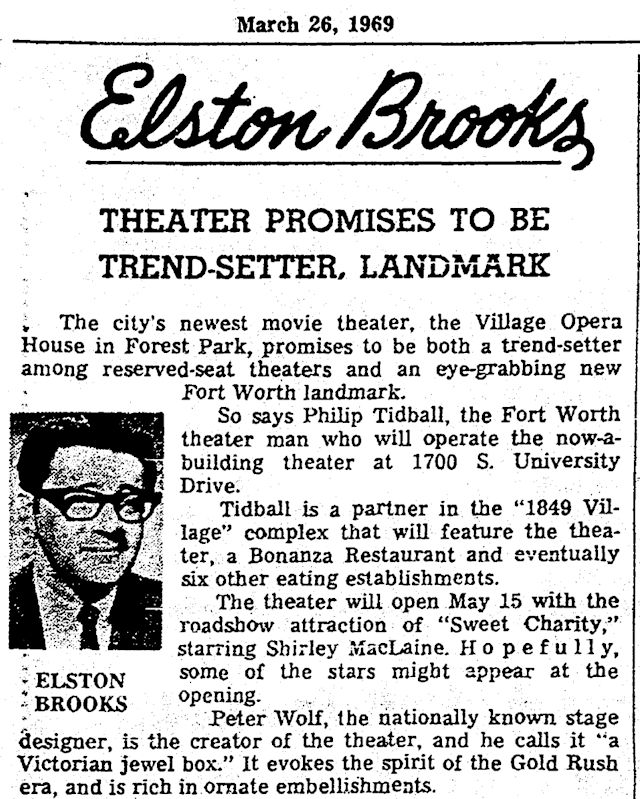

In 1969, as the era of Carlson’s restaurant was ending, something new was added to the University Drive “drag”: The 1849 Village restaurant-theater complex opened with the reserved-seating Village Opera House theater.

In 1969, as the era of Carlson’s restaurant was ending, something new was added to the University Drive “drag”: The 1849 Village restaurant-theater complex opened with the reserved-seating Village Opera House theater.

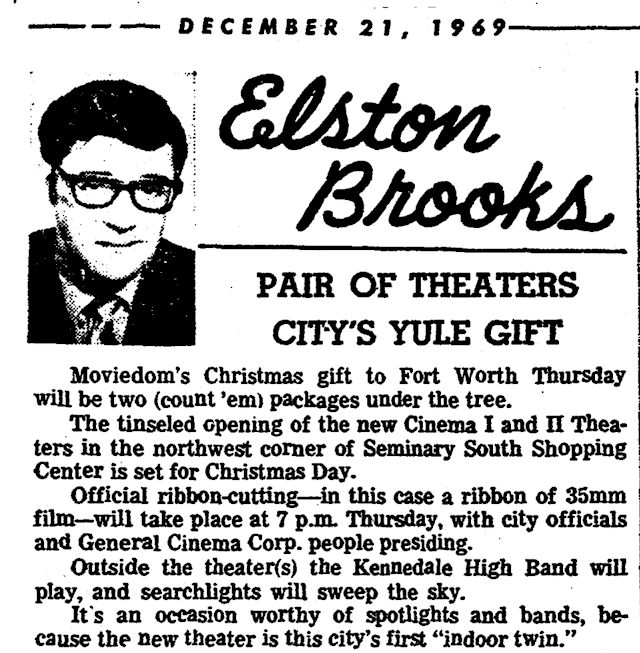

Later that year, Elston Brooks wrote, Fort Worth got “the city’s first ‘indoor twin’” as the Cinema I and II Theaters opened at Seminary South.

Later that year, Elston Brooks wrote, Fort Worth got “the city’s first ‘indoor twin’” as the Cinema I and II Theaters opened at Seminary South.

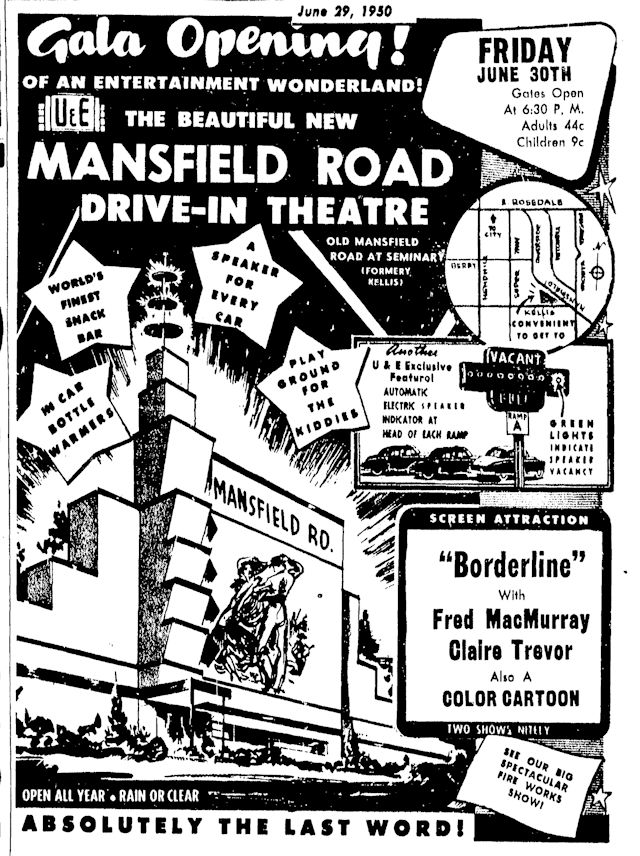

The Mansfield Road drive-in theater had opened in 1950 as “an entertainment wonderland” that was “open all year, rain or clear.”

The Mansfield Road drive-in theater had opened in 1950 as “an entertainment wonderland” that was “open all year, rain or clear.”

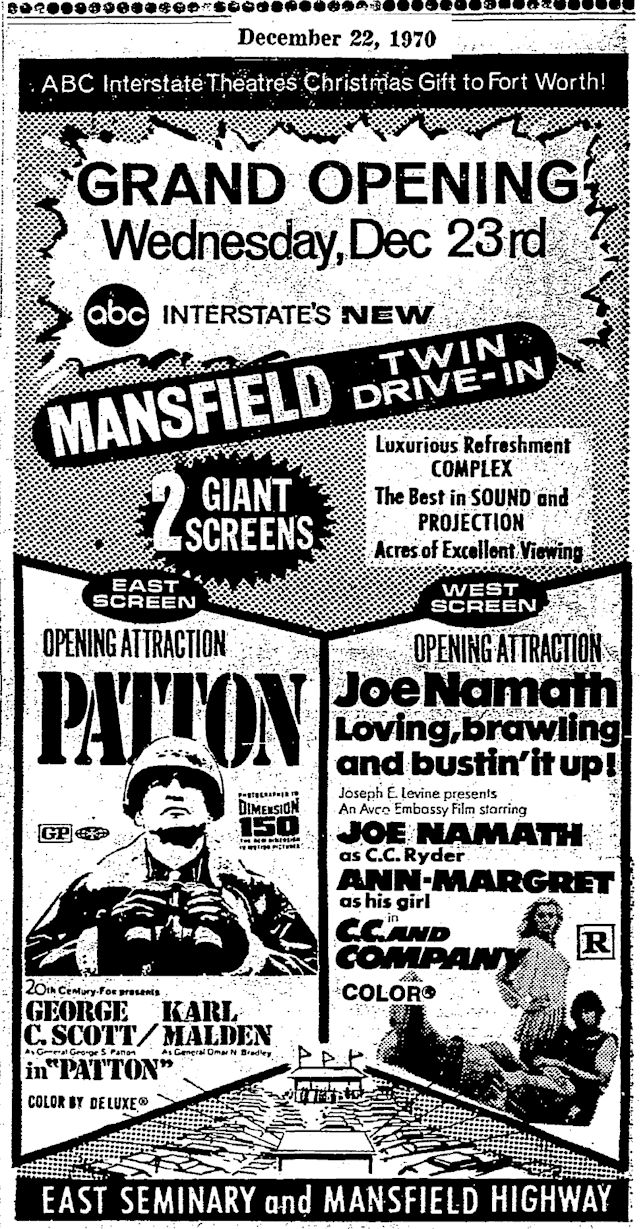

Twenty years later the only-child screen of the Mansfield got a sibling as the ABC Interstate chain—successor to the Interstate chain—opened the Mansfield twin drive-in theater.

Twenty years later the only-child screen of the Mansfield got a sibling as the ABC Interstate chain—successor to the Interstate chain—opened the Mansfield twin drive-in theater.

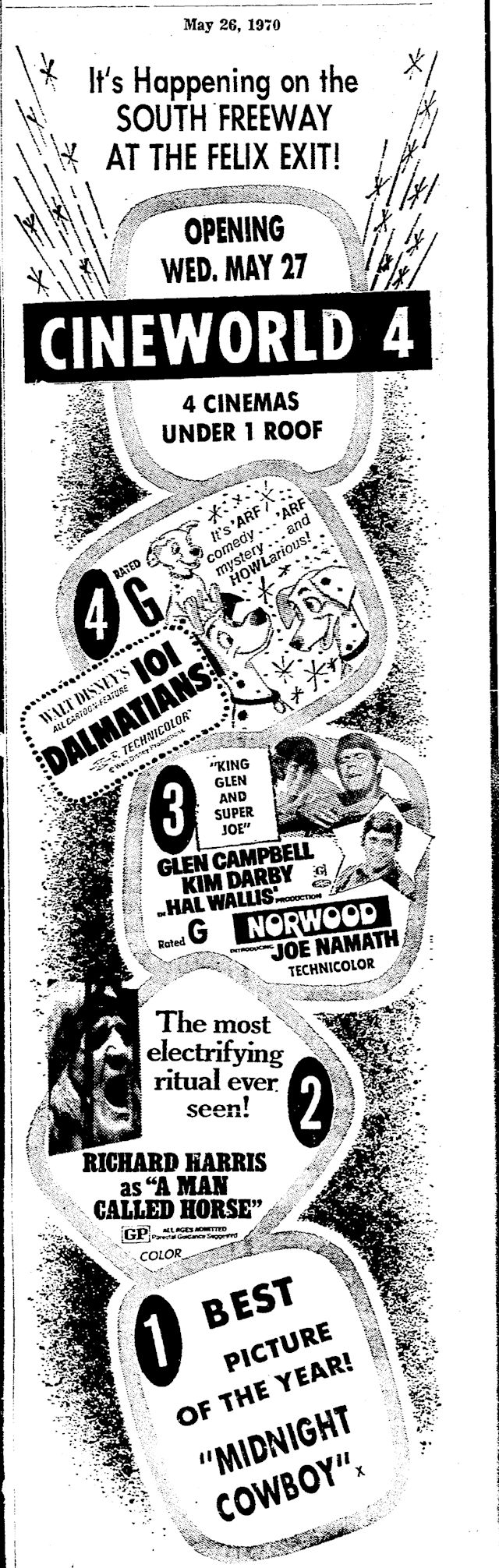

Aside from 1969’s two-screen Cinema I and II Theaters at Seminary South, the era of the multiplex really began in the 1970s. As best I can tell, Fort Worth’s first multiplex was the four-screen Cineworld 4 Cinemas, which opened in 1970 on the South Freeway at Felix where the Southside drive-in theater had been since at least 1950.

Aside from 1969’s two-screen Cinema I and II Theaters at Seminary South, the era of the multiplex really began in the 1970s. As best I can tell, Fort Worth’s first multiplex was the four-screen Cineworld 4 Cinemas, which opened in 1970 on the South Freeway at Felix where the Southside drive-in theater had been since at least 1950.

But soon four screens in a multiplex would seem paltry as four became six became eight became ten, ad Jawseam.

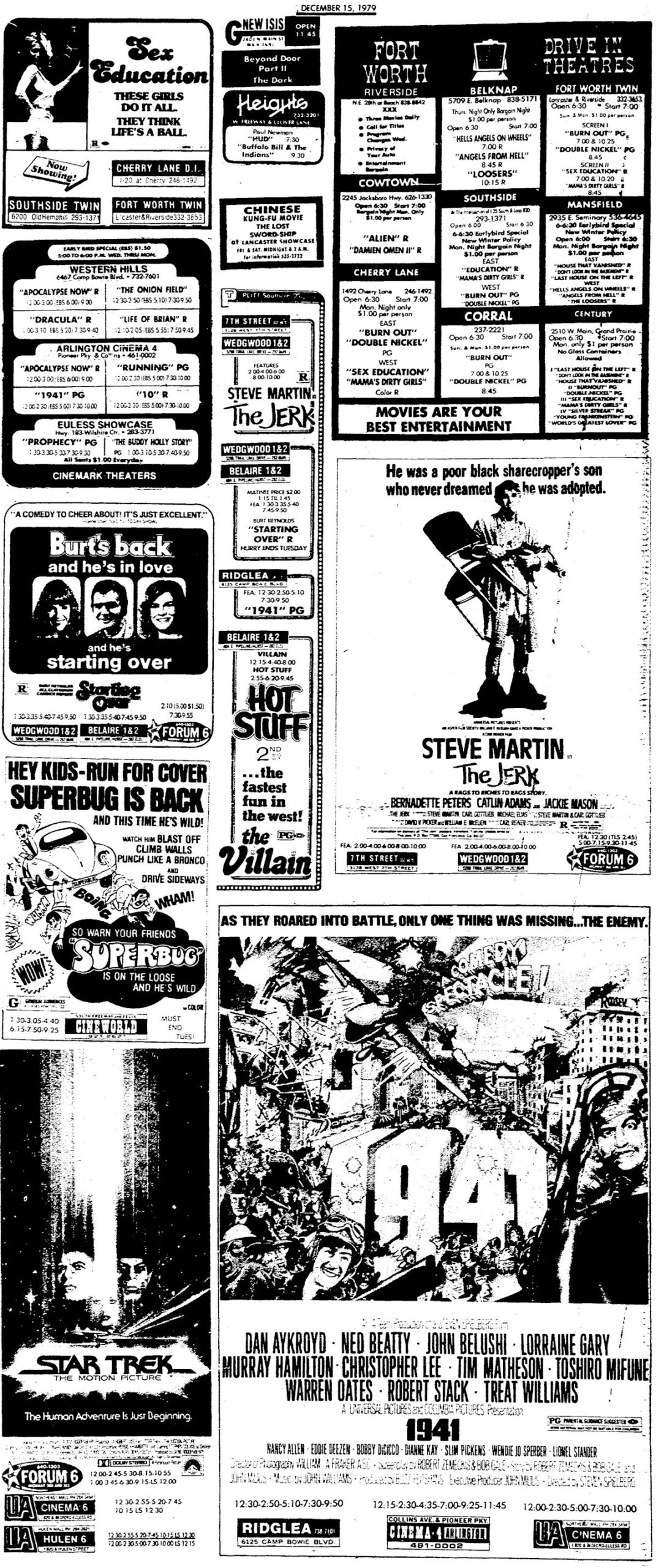

By 1979 Fort Worth had several multiplexes, including the Belaire 1&2, Wedgwood 1&2, Arlington Cinema 4, Euless Showcase, Western Hills, Forum 6, UA Cinema 6, and UA Hulen 6.

By 1979 Fort Worth had several multiplexes, including the Belaire 1&2, Wedgwood 1&2, Arlington Cinema 4, Euless Showcase, Western Hills, Forum 6, UA Cinema 6, and UA Hulen 6.

As theaters increased the number of screens, they decreased the size of auditoriums. And soundtracks bled through the walls between adjacent auditorims of multiplexes. Thus, in 1979 patrons watching, for example, The Muppet Movie on screen 1 had to tune out the soundtrack of Apocalypse Now next door on screen 2:

As theaters increased the number of screens, they decreased the size of auditoriums. And soundtracks bled through the walls between adjacent auditorims of multiplexes. Thus, in 1979 patrons watching, for example, The Muppet Movie on screen 1 had to tune out the soundtrack of Apocalypse Now next door on screen 2:

“Someday we’ll find it

The Rainbow Connection

The lovers, the dreamers and—”

“the smell of napalm in the morning.”

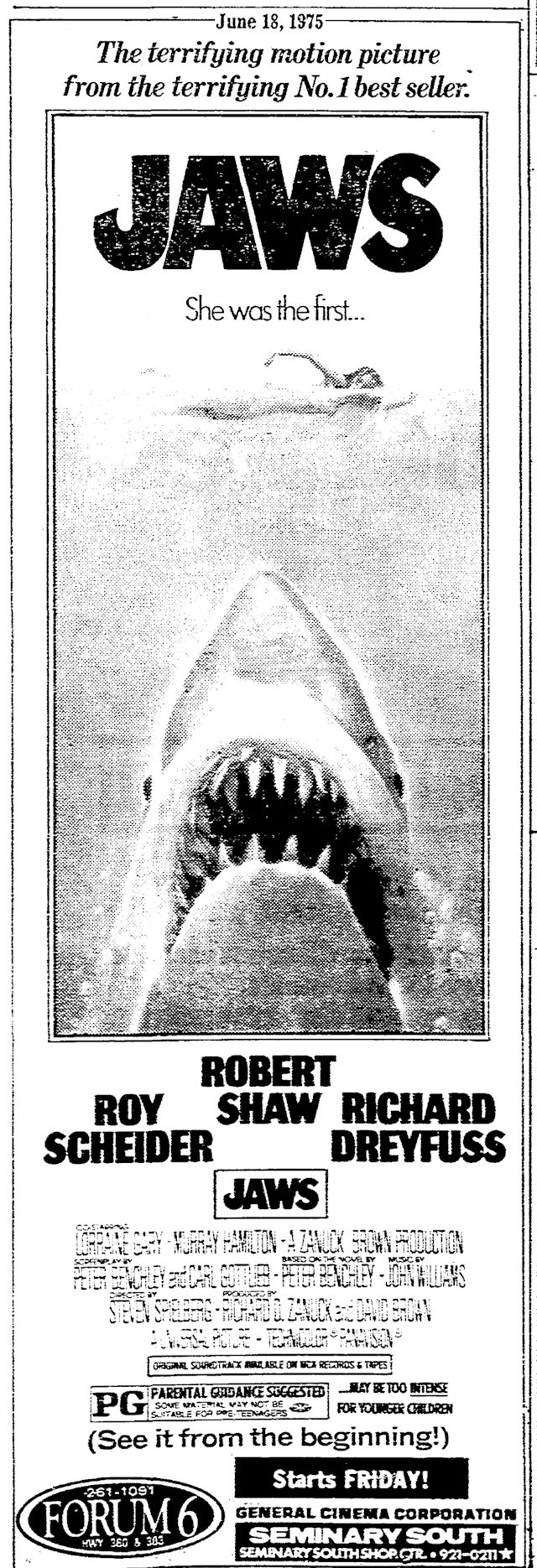

Speaking of mortal terror, in 1975 the blockbuster Jaws opened in Fort Worth.

Speaking of mortal terror, in 1975 the blockbuster Jaws opened in Fort Worth.

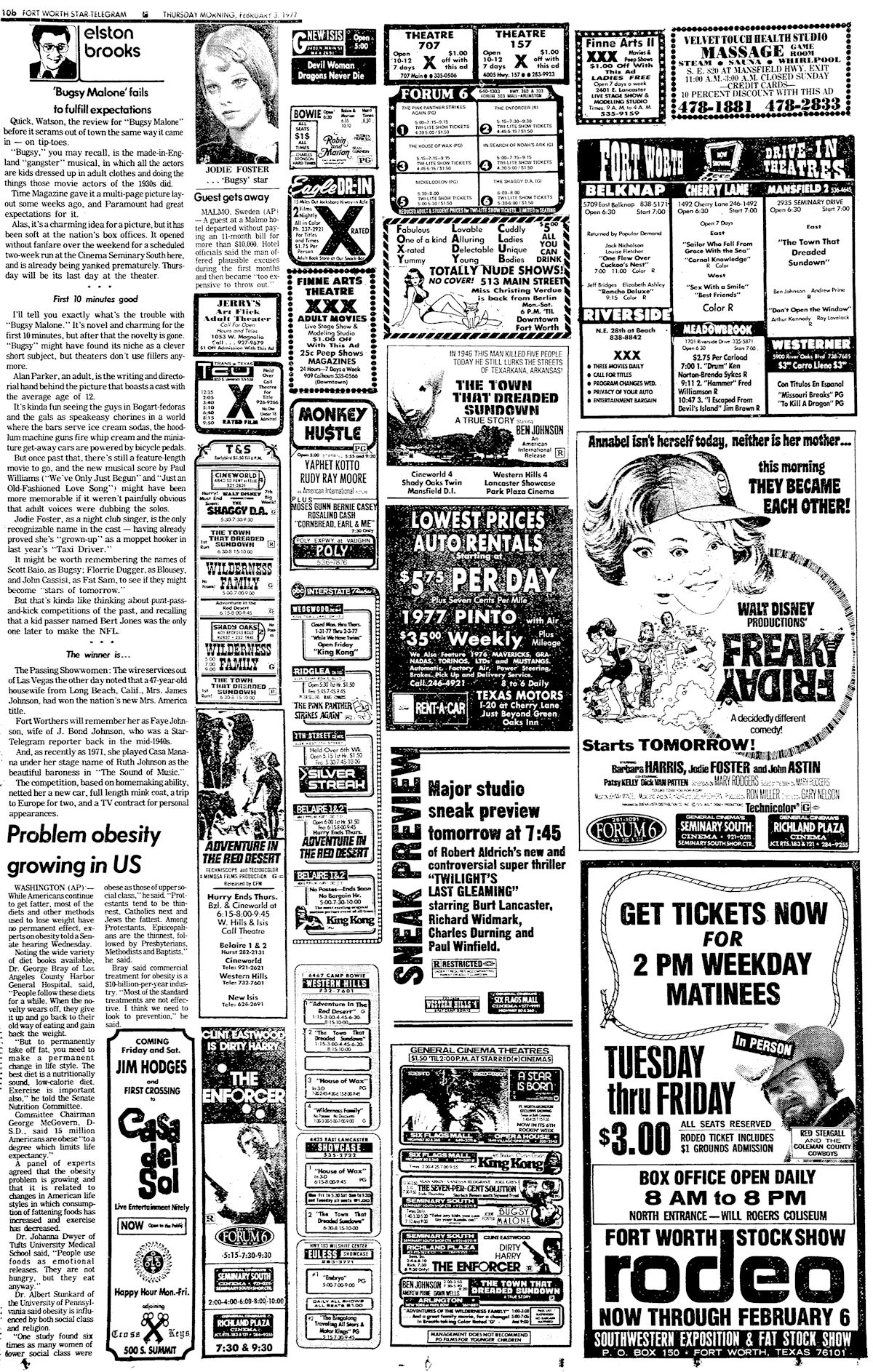

1977

By 1977 Star-Telegram entertainment columnist Elston Brooks had been writing about movies for twenty-eight years.

By 1977 Star-Telegram entertainment columnist Elston Brooks had been writing about movies for twenty-eight years.

Notice anything missing among the theater ads? By 1977 downtown’s Big Four were gone. The Majestic closed in 1964. The three theaters of Show Row closed during the 1970s: Worth, 1971; Palace, 1974; Hollywood, 1976.

Look back at the ad for Jaws in 1975. For the first time in a half-century a blockbuster movie had not opened at a Show Row theater. It had opened at the Forum 6 and Seminary South.

Why?

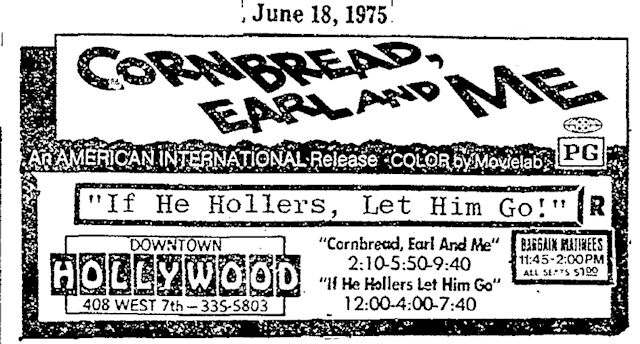

Because by the time Jaws “duh-duh . . . duh-duh . . . duh-duh duh-duh duhduh duhduh duhduh duhduh duhduh”ed into town, the mighty Interstate chain was gone, and three of downtown’s Big Four—members of that chain—had closed. The lone survivor, the Hollywood, was showing, the Star-Telegram reported, “films appealing predominately to black audiences.”

Because by the time Jaws “duh-duh . . . duh-duh . . . duh-duh duh-duh duhduh duhduh duhduh duhduh duhduh”ed into town, the mighty Interstate chain was gone, and three of downtown’s Big Four—members of that chain—had closed. The lone survivor, the Hollywood, was showing, the Star-Telegram reported, “films appealing predominately to black audiences.”

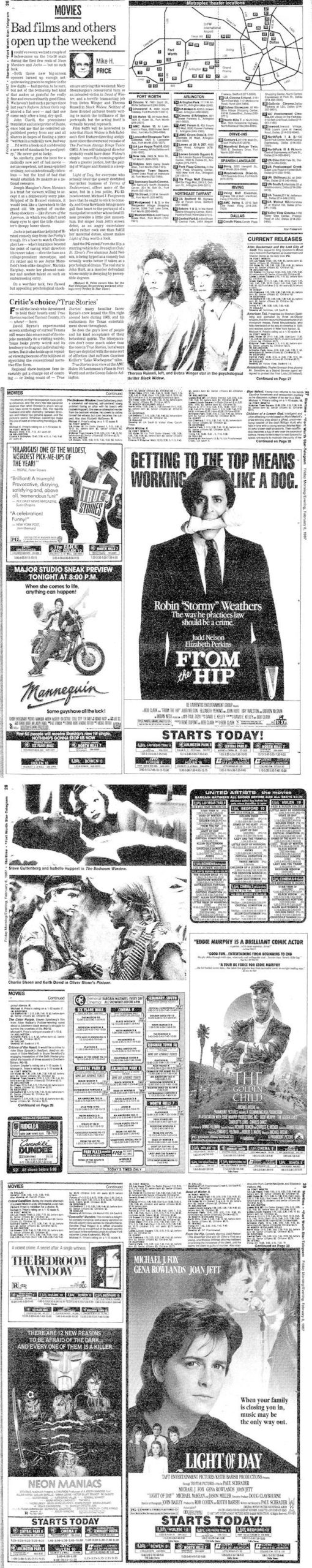

1987

Nonetheless, by February 6, 1987 movies took up eight pages in the weekend entertainment guide Star Time. Ninety years earlier, on February 6, 1897, the entire edition of the Fort Worth Morning Register was only eight pages!

Nonetheless, by February 6, 1987 movies took up eight pages in the weekend entertainment guide Star Time. Ninety years earlier, on February 6, 1897, the entire edition of the Fort Worth Morning Register was only eight pages!

The first page of the Star Time listings has a map showing Metroplex theaters—thirty-two of them in Tarrant County. There is also a list of Fort Worth theaters. Of the theaters mentioned in this blog post, the New Isis (1936) easily had seniority over all other theaters in 1987. The 7th Street Theater (1948) was second in seniority. Third was the Ridglea (1950). The Isis would close in 1988.

As the nature of Fort Worth’s theaters changed from the opulent downtown cathedrals of cinema to the neighborhood one-screeners to the suburban multiplexes, motion picture technology also changed.

Hollywood began using different formats of lenses and film. For example, CinemaScope is an anamorphic lens series used from 1953 to 1967 to shoot widescreen movies (The Robe, How to Marry a Millionaire, Love Me Tender).

VistaVision is a widescreen film format created by Paramount Pictures in 1954 (White Christmas, One-Eyed Jacks).

Dolby sound was introduced in 1971 in A Clockwork Orange.

In the 1980s the film format Super 35 (originally known as “Superscope 235”) was introduced (Top Gun, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off).

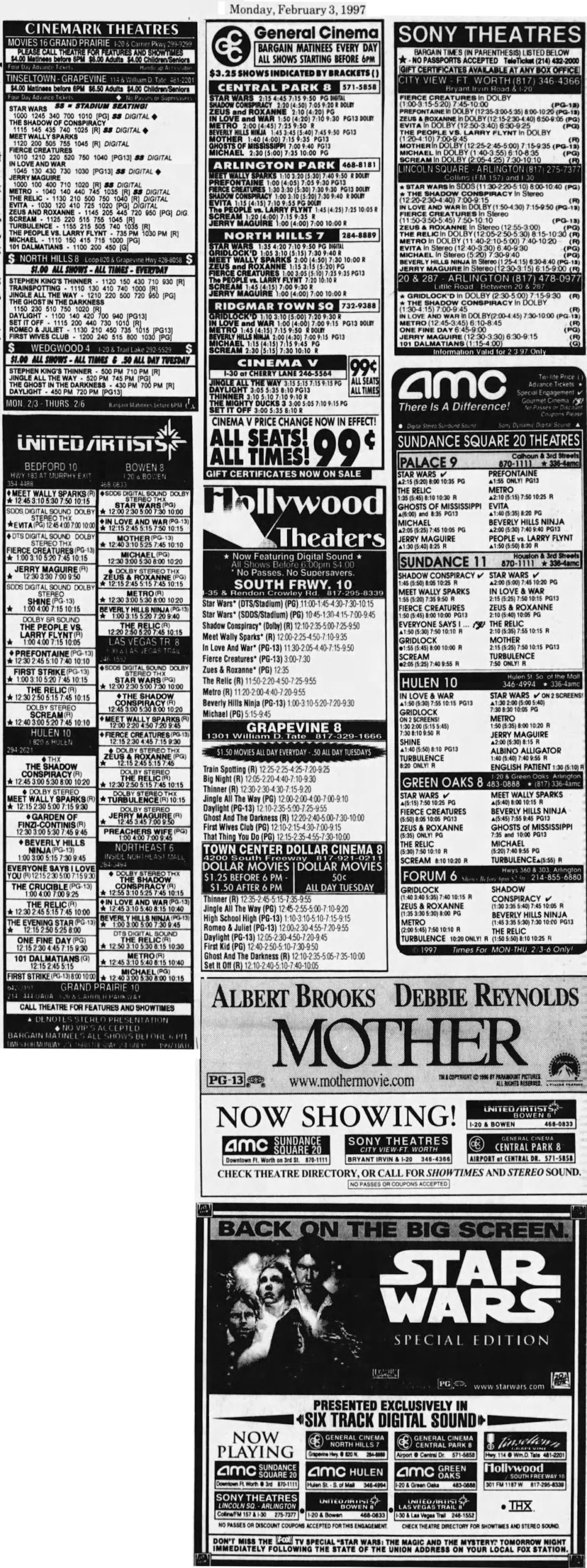

1997

By 1997, a century after Edison’s Vitascope had enthralled patrons at Greenwall’s Opera House, Fort Worth had more than twenty theaters, most owned by chains. Most had multiple screens—at least one with sixteen screens.

By 1997, a century after Edison’s Vitascope had enthralled patrons at Greenwall’s Opera House, Fort Worth had more than twenty theaters, most owned by chains. Most had multiple screens—at least one with sixteen screens.

Gone were the opulent downtown theaters and the neighborhood theaters.

Gone were the drive-in theaters.

Gone were the splashy newspaper ads for the opening of blockbuster films.

Gone were the movie premieres with personal appearances by the stars.

Gone were the reviews and interviews by Brooks, Gordon, Perry Stewart.

Gone was the Worth Theater’s mighty Wurlitzer organ.

Gone with the wind.

Among the films that Fort Worth was watching in 1997, a century after its cinematic history had begun with the Edison Vitascope, was Evita. Evita was 135 minutes long, featured Dolby digital sound, was filmed in four countries, employed a cast and crew of hundreds (and thousands of extras), required eighty-five costume changes by star Madonna, and cost an estimated $55 million ($90 million today) to make.

What would the Wizard of Menlo Park think of that?