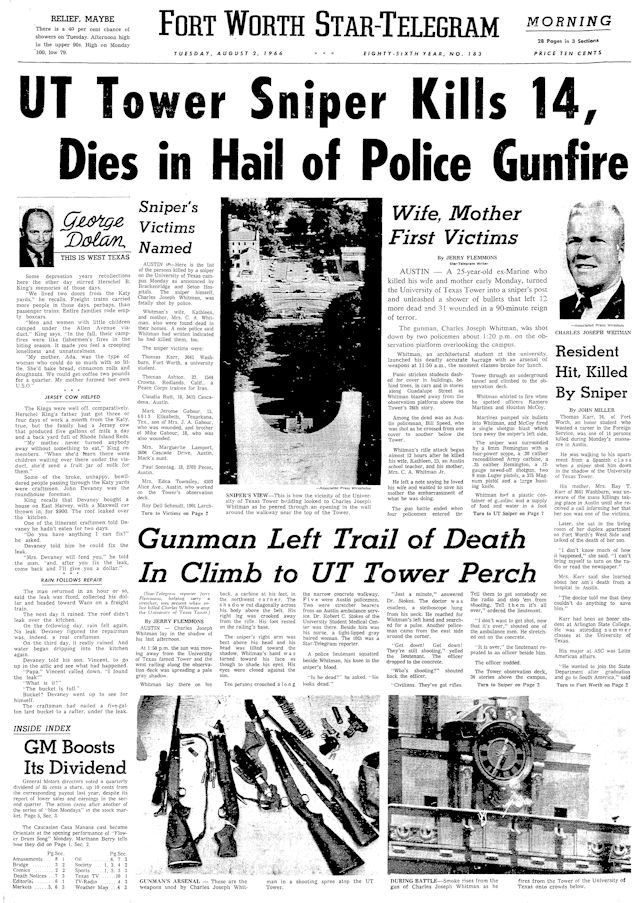

On August 1, 1966, just hours after killing his mother and wife, Charles Whitman, twenty-five, entered the Tower on the campus of the University of Texas in Austin. Armed with four rifles and other guns he killed three people in the tower and then went to the observation deck on the twenty-eighth floor, where he shot and killed eleven more people before he was killed by police.

In Fort Worth during the weeks that followed it seemed as if the tortured soul of Charles Whitman were still pulling the trigger.

In Fort Worth during the weeks that followed it seemed as if the tortured soul of Charles Whitman were still pulling the trigger.

Five days after Whitman’s sniper rampage, two young men from Falls County shot to death two teenage boys near Burleson and raped and fatally strangled the boys’ teenage female companion.

Eight days after Whitman’s sniper rampage, a Fort Worth teenager bought a .303-caliber rifle. He had never before fired a gun.

In the following days he fired the rifle twice.

On September 1 he fired the rifle a third time. In a sniper ambush at Lake Arlington he killed two people with a single shot.

On September 22 he fired the rifle a fourth time, killing another person at Lake Arlington.

Six people dead.

All three killers would be arrested, convicted of murder, and sent to prison. But twenty-three years later one of the three would be paroled and immediately begin to kill again until the total killed by the three men may have equaled that of Charles Whitman.

Two of the three killers represented the extremes of personality: At one extreme was “absolutely the most vicious and savage individual I know,” according to one Texas lawman; at the other extreme was “a good boy . . . who could get along with anybody,” according to his father.

In between was a sidekick who just followed orders.

In the end, of course, the victims of the “savage individual,” the “good boy,” and the obedient sidekick were equally dead.

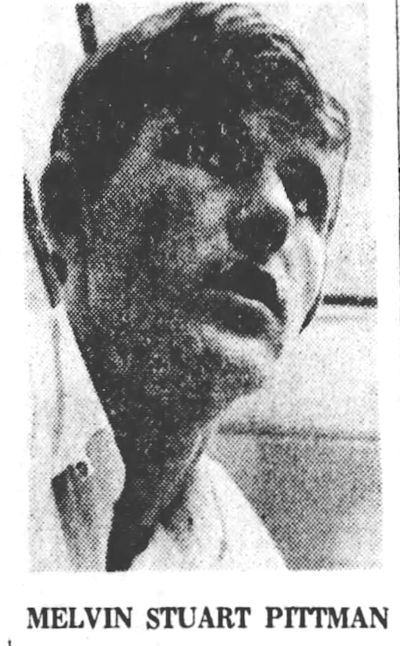

Melvin Stuart Pittman, eighteen, lanky and dark blond, was a junior at Trimble Technical High School. He was one of seven children. His father Will was a carpenter. The Pittmans lived on Nelms Street in east Fort Worth just west of Arlington Lake.

Melvin Stuart Pittman, eighteen, lanky and dark blond, was a junior at Trimble Technical High School. He was one of seven children. His father Will was a carpenter. The Pittmans lived on Nelms Street in east Fort Worth just west of Arlington Lake.

Melvin was a year behind in school, wanted to drop out and join the Army, but his father encouraged him to stay in school.

Will Pittman later told the Star-Telegram: “We’ve always worked, had to with seven kids. Melvin always helped. He worked in filling stations, and he mowed lawns on Saturdays. He could get along with anybody—he always had friends coming by, boys and girls.

“Anybody in this neighborhood will tell you he was a good boy. One time he drank one can of beer, but that was the only time. He never even got a traffic ticket, never been in trouble. I never saw a kid with more friends.”

The Star-Telegram later wrote that Melvin’s mother said her son had spoken to her about the Whitman massacre: “He would read about that sniper down at Austin, and he would say, ‘What a shame those people had to die.’

“He didn’t even like war movies where there was death,” she said.

But on August 9 Melvin used thirty dollars of his filling stations-and-lawns money to buy a .303-caliber rifle at a pawn shop.

Will Pittman later said: “I guess that’s really the only argument I ever had with him. He saved his money to buy that gun, and when he brought it around to show it to me I told him I wouldn’t have a gun in this house. But I wanted him to stay in school, and I thought maybe this gun would make him happy, so I gave in” with one condition—that the rifle’s bolt-action mechanism be kept in Mrs. Pittman’s purse at all times.

Sometime between August 9 and September 1 Melvin took the bolt action from his mother’s purse.

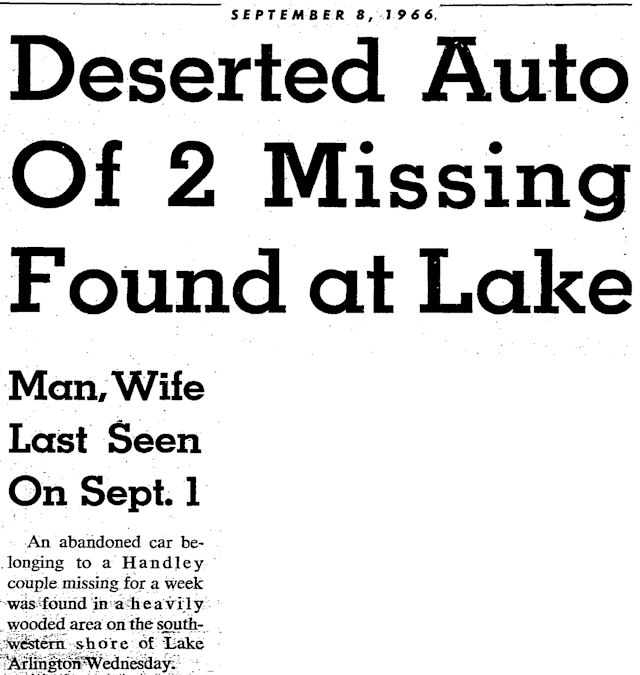

On September 6 Mrs. Paul Hinman reported to police that her parents, Victor and Dorene Laird of Handley, had not been seen since September 1.

On September 7 the Lairds’ car was found in a heavily wooded area on the southwestern shore of Lake Arlington.

On September 7 the Lairds’ car was found in a heavily wooded area on the southwestern shore of Lake Arlington.

Two weeks later, on September 22, Kenneth Eugene Jones, thirty-five, drove to the southwestern shore of Lake Arlington after work to fish. Jones, who managed the local branch of a Houston investment company, lived in a mobile home park on the western shore of the lake. He and his ex-wife were going to remarry on September 24.

Jones took his fishing gear from the trunk of his car, a 1965 Mustang, and walked to the water’s edge. Nearby he saw a lanky, dark-blond young man who also was fishing.

Jones struck up a conversation with the young man.

About 3:30 a.m. the next morning Fort Worth police officer L. D. Cates was on patrol near Inspiration Point at Lake Worth when he spotted a 1965 Mustang speeding. Cates gave chase at speeds up to 110 miles per hour before the driver of the Mustang pulled over on Jacksboro Highway.

Melvin Stuart Pittman told Cates that he had attended a beer party at Lake Arlington, where he had borrowed the car from a friend—a friend whose name he did not know.

Suspicious, Cates took Pittman to police headquarters to be booked on suspicion of auto theft.

Police used documents found in the car to determine that it was a company car assigned to Kenneth Eugene Jones, manager of the Fort Worth branch of the Gulf Coast Investment Company of Houston.

Police informed the branch office that Jones’s car had been found.

Fort Worth police detective Jack Bennett said, “We were waiting for Jones to come in to claim the car when his secretary called us.”

The woman was alarmed, said Jones hadn’t been to the office that day, that “he always checks with us by phone. It’s not like him at all.”

When police questioned Pittman about how the car came into his possession, he gave a different account than he had given officer Cates.

After police interviewed Jones’s neighbors, they told Pittman that his story did not stand up, that the car belonged to Jones, who was missing.

Pittman stuck to his story.

Police asked him to take a polygraph test. He refused.

Soon after he confessed.

That night police detectives took Melvin to his home. He showed them the rifle and told them he had used it to kill the Lairds and Jones.

Melvin’s later father said of his son, “He’d only fired that rifle twice. Twice until those people—that’s the only time he ever shot a gun or practiced with one. . . . He’d never met any of those people, I know. I wondered . . . about that man Jones—does he have a wife and kids?—that man is just six years younger than me, he deserved his life, he shouldn’t have died.”

Police detectives then took Melvin Pittman to the lake, where he led them to the bodies by flashlight. The area was so inaccessible that police placed flares to guide ambulance attendants to the bodies. (The headline says only one body had been found. Apparently the morning Star-Telegram had gone to press before the bodies of the Lairds were found later that night.)

Police detectives then took Melvin Pittman to the lake, where he led them to the bodies by flashlight. The area was so inaccessible that police placed flares to guide ambulance attendants to the bodies. (The headline says only one body had been found. Apparently the morning Star-Telegram had gone to press before the bodies of the Lairds were found later that night.)

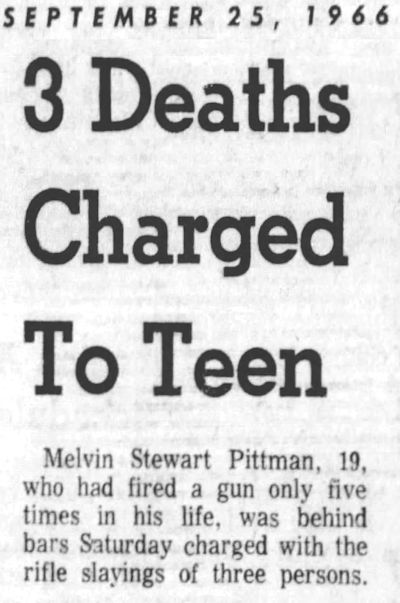

Pittman was taken back to the county jail and charged with three murders.

Pittman was taken back to the county jail and charged with three murders.

He could give no motive for his actions.

“I don’t have any reasons,” he said without emotion.

When he was returned to his jail cell he showed police a shell casing he had hidden in the cell after being jailed for auto theft.

The next day he turned nineteen.

Also in the county jail were Kenneth Allen McDuff and Roy Dale Green (see Part 2).

Pittman told investigators that on September 1 he had gone to the lake to shoot water moccasins. He saw the Lairds, who often fished at the lake, walking in waist-deep Johnson grass. He was concealed in scrub brush as he watched them.

He told an investigator that he had wanted to see if he could kill both victims with a single bullet.

He did.

Pittman told investigators that on September 22 he again was at Lake Arlington about 7 p.m. when Jones drove up and took fishing gear out of his car’s trunk. Jones walked down to the water’s edge near Pittman, and the two began to talk “about fishing and all that stuff.”

After about two hours Jones began to walk away. When he was about twenty steps away, Pittman raised his rifle and hollered, “Hey.”

“And when I did he turned his head toward me, and I shot him. I fired just the one time, and he dropped straight down, and I went to look at him, and he looked like he was dead, so I drug him by the feet not quite a city block over into some brush and took three dollars off him.”

Five days later, on September 27, Pittman was interviewed in his cell by a Star-Telegram reporter. Now Pittman spoke differently about the Charles Whitman massacre: “It sounds like that guy had himself a real blast.”

Five days later, on September 27, Pittman was interviewed in his cell by a Star-Telegram reporter. Now Pittman spoke differently about the Charles Whitman massacre: “It sounds like that guy had himself a real blast.”

On March 3, 1967 testimony began in the trial of Melvin Stuart Pittman, charged with the murder of Kenneth Eugene Jones. The state sought the death penalty. Pittman had entered a plea of not guilty.

On March 3, 1967 testimony began in the trial of Melvin Stuart Pittman, charged with the murder of Kenneth Eugene Jones. The state sought the death penalty. Pittman had entered a plea of not guilty.

His court-appointed attorney did not deny that Pittman killed Jones. Instead the attorney argued that Pittman had not been adequately advised of his rights before being questioned by police. Assistant District Attorney Charles Butts countered that Pittman had received three warnings from judges and from Butts before signing a confession.

The confession was read twice to the jury.

Pittman did not take the witness stand.

On March 7 Pittman was found guilty and sentenced to death.

On March 7 Pittman was found guilty and sentenced to death.

A bailiff said Pittman whistled as he left the courtroom.

Pittman later said he felt that the jury had predetermined to sentence him to the electric chair.

He said that if he had been on the jury in such a case he would have voted to sentence the defendant to Rusk State Hospital (which provides psychiatric treatment).

“Anybody who would go out and kill three people is bound to have something wrong with him.”

In 1969, four days before he was scheduled to die, Pittman was granted an indefinite stay of execution after his attorneys in an application for a writ of habeas corpus found fault with police interrogation of Pittman and with conduct of his trial.

In 1969, four days before he was scheduled to die, Pittman was granted an indefinite stay of execution after his attorneys in an application for a writ of habeas corpus found fault with police interrogation of Pittman and with conduct of his trial.

In 1972 Pittman’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment when the U.S. Supreme Court declared the death penalty unconstitutional.

By 1994 Pittman, then forty-six, was still in the penitentiary in Huntsville, where he had been turned down for parole seventeen times. His application for parole was due to be reviewed again in 1995.

Mrs. Kathryn Jones, the woman whom Kenneth Eugene Jones was to have remarried two days after he was killed, began a campaign to urge the parole board not to release Pittman.

“Pittman got his grace from God when he got his stay of execution,” Kathryn Jones said. “So what if he has to spend the rest of his life locked up? He has his life. Kenneth doesn’t even have his life.”

She recalled that on September 22, 1966—twenty-eight years earlier—she and her two daughters and son Johnny had driven to the mobile home park near Lake Arlington where her ex-husband had been living since their divorce. Kenneth and Kathryn planned to drop the children off at her parents’ house and drive to Oklahoma and get remarried.

When Kathryn Jones and her children reached her ex-husband’s mobile home, they found a note tacked to the door: “Gone fishing at my usual place. Johnny knows the spot. Come on down.”

But when they reached the spot, they couldn’t find Jones. Melvin Stuart Pittman had gotten there first.

“I was planning on getting married on the weekend,” Kathryn Jones recalled in 1994, “and I was at a funeral on Sunday.”

Melvin Stuart Pittman was denied his parole in 1995.

The “good boy” who killed three strangers died in Huntsville penitentiary in 2012.

Melvin was my uncle, his brother Steven was my dad he passed away in 2020 I remember the the paper calling my dad about doing an interview…I was always interested in this we have been told multiple different stories about what happened

Happy to hear that Mr. Taylor learned from Melvin’s mistakes. My mother would have loved to have her mother around for much longer so she could introduce her to her grandchildren. Instead she received an early death penalty and left on the side of a lake like a piece of trash. Due to the Supreme Court Melvin received life giving his loved ones opportunities to see him. In the end my mother and her sibling’s would have been happy to hear how badly he wanted to be paroled knowing that their letters to the parole board were part of the reason that would not happen. 17 & 18 year olds know what consequences are. Just like many other criminals he thought he was smart enough to get away with it and would have if he wouldn’t have stolen that car. My opinion of him stating he wish he could do it over again, means I wish I wouldn’t have stolen that car. In the end justice was served, but the right sentence was avoided.

I spent 5 yrs on Ellis unit with Melvin,I worked side by side with him 5 days a week refurbishing school busses. I left shortly after he passed. He died of a heart attack in his cubicle. He taught me so much.Most important lesson was not to take my freedom for granted and never forget where I was, there with him. He would have given anything to have a chance at life.He told me numerous times that he was just a young stupid kid that had no idea of the consequences of his actions. If only he could go back any change what he had done. I’m here to tell you he was a great man in the end. He loved fixing those school busses for those kids. It gave meaning to his life in there. I think of him alot from time to time. I’ll never go down the road I was on again thanks to Melvin Pittman telling me I would give anything to have a chance at parole, Don’t take it for granted son! You wind up like me never getting out of here. I pray for his soul, he was a great man in my eyes!

Thank you, Mr. Taylor, for your first-hand account.

I have never heard of this. I recently did a podcast on the UT Sniper and am now writing a companion piece (book) about those events with the main question being, Why? I have been looking for what to cover next. Your article is very well written and ghoulishly fascinating yet, of course, disturbing. I have never given much thought about those influenced by Whitman. I am sure there are others. These things are bothersome and they will always remain inexplainable, though we try. Glad I ran across your story.

Thanks, Kim. Yeah, you gotta wonder how many “copy cats” Whitman inspired. Copy cat crimes are much more recognized as a phenomenon now than they were then, I suspect. “Ghoulishly fascinating” just about covers it.

the baby faced killer and my brother in law

https://law.justia.com/cases/texas/court-of-criminal-appeals/1978/52325-3.html