If you were born in the middle of the twentieth century, you probably remember the 1960s with a smile: the advent of the Beatles and the Ford Mustang in 1964, the Summer of Love in 1967, the premiere of Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In and the first flight to the moon by the crew of Apollo 8 in 1968, Woodstock in 1969.

But as the sixties began Americans didn’t have much to smile about amid the Cold War and its threat of nuclear annihilation.

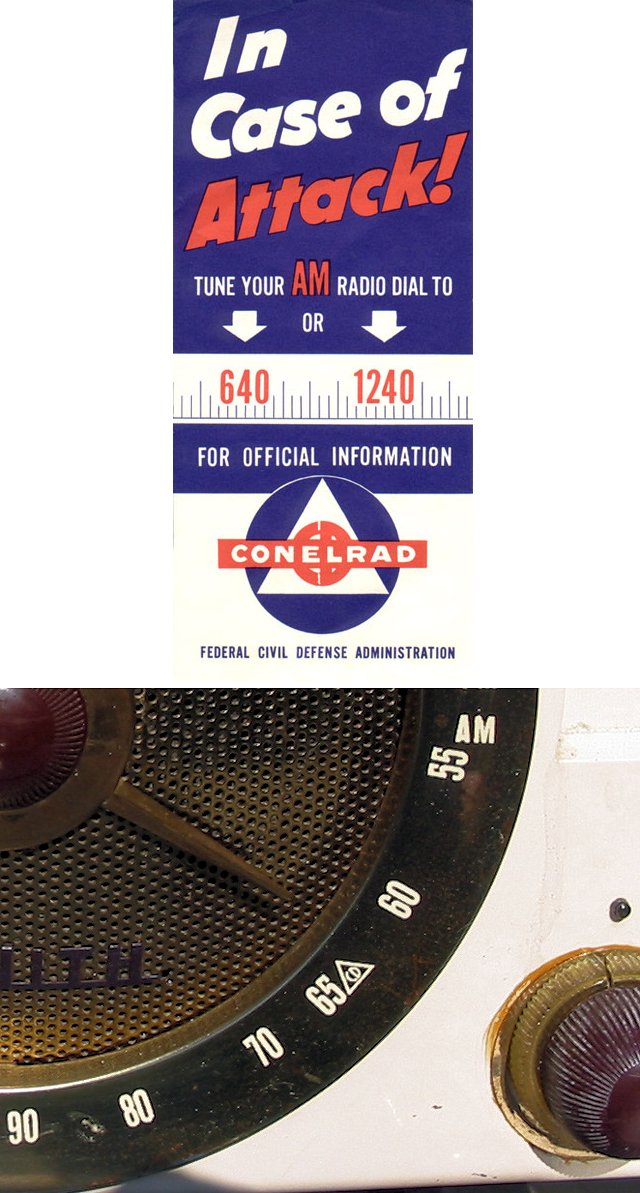

Who can recall the years 1960-1962 without feeling the urge to tune their AM radio to CONELRAD’s little “CD” on the dial at the 640 and 1240 kHz frequencies?

Who can recall the years 1960-1962 without feeling the urge to tune their AM radio to CONELRAD’s little “CD” on the dial at the 640 and 1240 kHz frequencies?

Even today, when the sirens of the City of Fort Worth Outdoor Warning System are tested at 1 p.m. each Wednesday, I crawl under a table with a week’s supply of canned food.

Indeed, before we even entered the uncertain sixties, the fretful fifties had put America on edge. Did all those 1950s sci-fi movies about Earthlings being menaced by aliens from outer space armed with powerful weapons reflect our angst about the threat of Russia and its nuclear weapons?

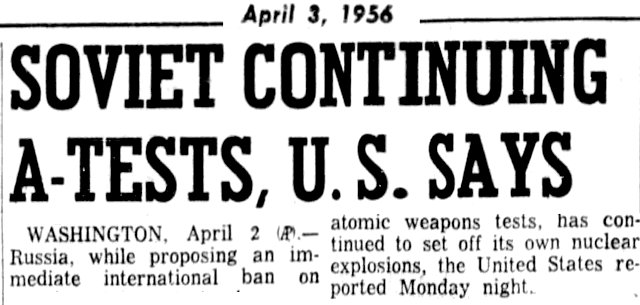

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev set the ominous tone for my adolescence in 1956 when he said to Western ambassadors: “My vas pokhoronim!” That was translated by some to mean “We will bury you.” And Russia was developing a really big shovel.

And Russia was developing a really big shovel.

I was seven years old, for God’s sake. What did Khrushchev have against me?

Dire headlines like that, the film Duck and Cover with Bert the Turtle, and civil defense drills in school kept the threat of war in the minds of everyone, even (especially?) kids.

Dire headlines like that, the film Duck and Cover with Bert the Turtle, and civil defense drills in school kept the threat of war in the minds of everyone, even (especially?) kids.

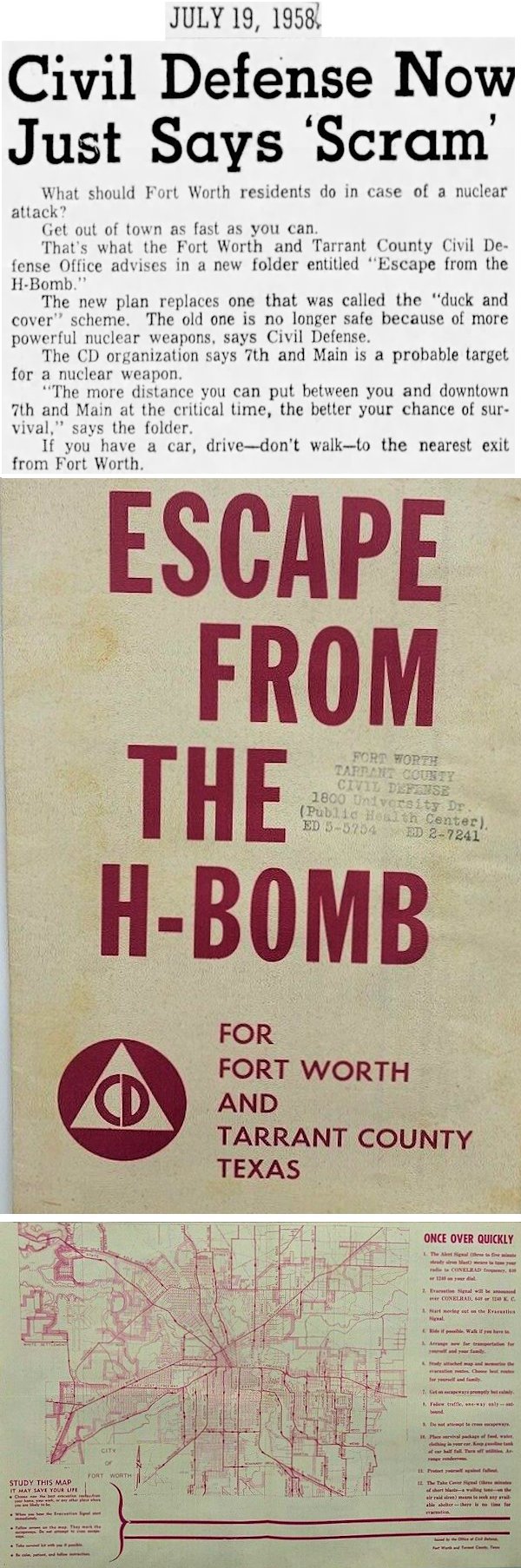

It got worse. In 1958 Fort Worth’s Civil Defense office told us that “duck and cover” would no longer save us. Evacuation would be our only hope because the Russians had their eye on the intersection of Main and 7th streets downtown! So, the Civil Defense office published a pamphlet (Escape from the H-Bomb) with an evacuation map and these instructions: “The ‘duck and cover’ scheme is no long safe—you must get away. An estimate of the situation indicates Seventh and Main Street in downtown as a possible target for a nuclear weapon. . . . Study this map. It may save your life. . . . 1. The Alert Signal (three to five minute steady blast) means to tune your radio to CONELRAD frequency, 640 or 1240 on your dial. 2. Evacuation Signal will be announced over CONELRAD. . . . 3. Start moving out on the Evacuation Signal. 4. Ride if possible. Walk if you have to. . . . 7. Get on escapeways promptly but calmly. . . . 10. Place survival package of food, water, clothing in your car. . . . 12. The Take Cover Signal (three minutes of short blasts—a wailing tone—on the air raid siren) means to seek any available shelter—there is no time for evacuation.”

I was nine years old. I lived less than two miles from the intersection of Main and 7th.

The sixties began no better. Ike may have been laughing in January 1960, but a U.S. general warned that a “Red Missile Attack” was possible by 1962.

The sixties began no better. Ike may have been laughing in January 1960, but a U.S. general warned that a “Red Missile Attack” was possible by 1962.

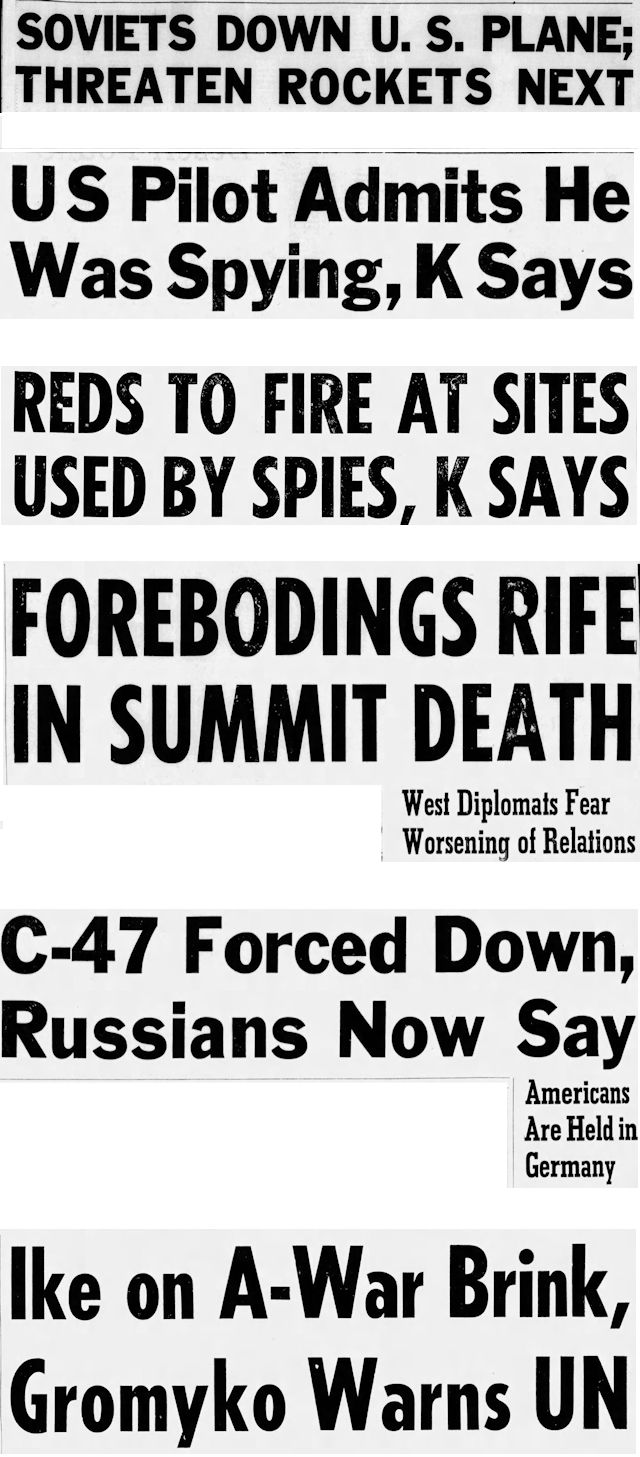

The front pages of the Star-Telegram in May 1960 were full of headlines about the threat of war as Russia downed U.S military planes. (“K,” of course, was Khrushchev, the guy who wanted to bury me.)

The front pages of the Star-Telegram in May 1960 were full of headlines about the threat of war as Russia downed U.S military planes. (“K,” of course, was Khrushchev, the guy who wanted to bury me.)

And the headlines certainly remained ominous in July 1960 as the United States worried that the Soviet Union would use Cuba as a military base just one hundred miles from Florida.

And the headlines certainly remained ominous in July 1960 as the United States worried that the Soviet Union would use Cuba as a military base just one hundred miles from Florida.

Meanwhile, the Russians shot down another U.S. reconnaissance plane—an RB-47—and accused the United States of aerial espionage despite denials by Eisenhower. Four of the six crew members were killed.

The Cold War remained in the news in August 1960 as the U.S. State Department charged that “Cuban Tie to Reds ‘Now in Open.’”

The Cold War remained in the news in August 1960 as the U.S. State Department charged that “Cuban Tie to Reds ‘Now in Open.’”

Cuba?! Cuba as in the Tropicana Club? Cuba as in “Guantanamera”? Cuba as in “I’ll see you in C-U-B-A”?

Say it ain’t so, Ricky!

And in Moscow, American U2 pilot Gary Powers, shot down by Russia in May, was tried, convicted, and sentenced to prison. Now Russia and the United States were playing chess at the megaton level and at the micro level.

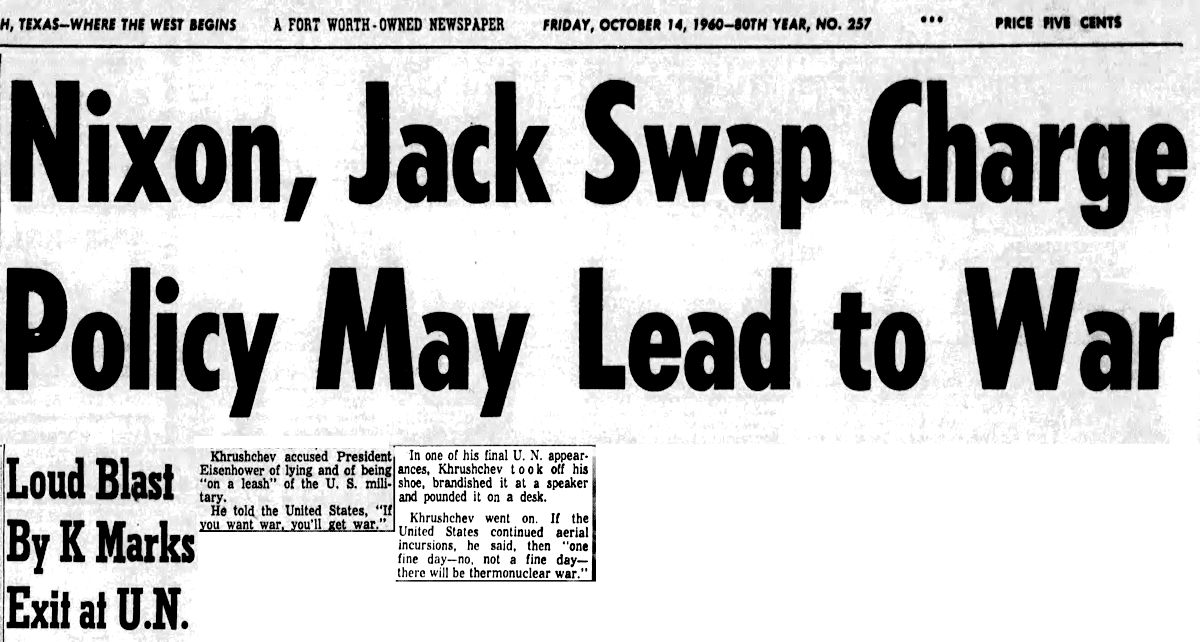

In October 1960 presidential nominees Richard Nixon and John Kennedy each warned voters that the other man’s policies could lead to war with Russia or China. Meanwhile, Khrushchev was cutting didoes at the United Nations, supposedly pounding his shoe on a desk.

In October 1960 presidential nominees Richard Nixon and John Kennedy each warned voters that the other man’s policies could lead to war with Russia or China. Meanwhile, Khrushchev was cutting didoes at the United Nations, supposedly pounding his shoe on a desk.

The Star-Telegram wrote:

“Khrushchev accused President Eisenhower of lying and of being ‘on a leash’ of the U.S. military.

“He told the United States, ‘If you want war, you’ll get war.’

“Khrushchev went on. If the United States continued aerial incursions, he said, then ‘one fine day—no, not a fine day—there will be thermonuclear war.’”

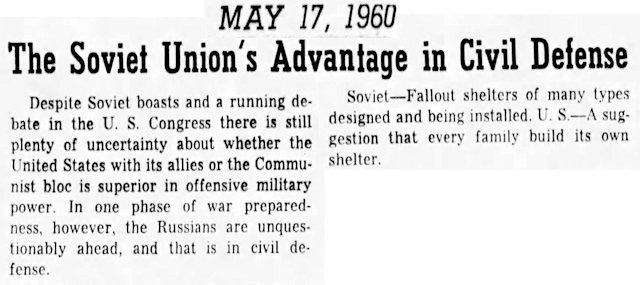

If nuclear war came, what could civilians do to survive it? Home fallout shelters were considered to be the best protection. But a Star-Telegram editorial in May 1960 warned that while the Russians were actually building shelters, the United States government was merely suggesting that every family build a fallout shelter.

If nuclear war came, what could civilians do to survive it? Home fallout shelters were considered to be the best protection. But a Star-Telegram editorial in May 1960 warned that while the Russians were actually building shelters, the United States government was merely suggesting that every family build a fallout shelter.

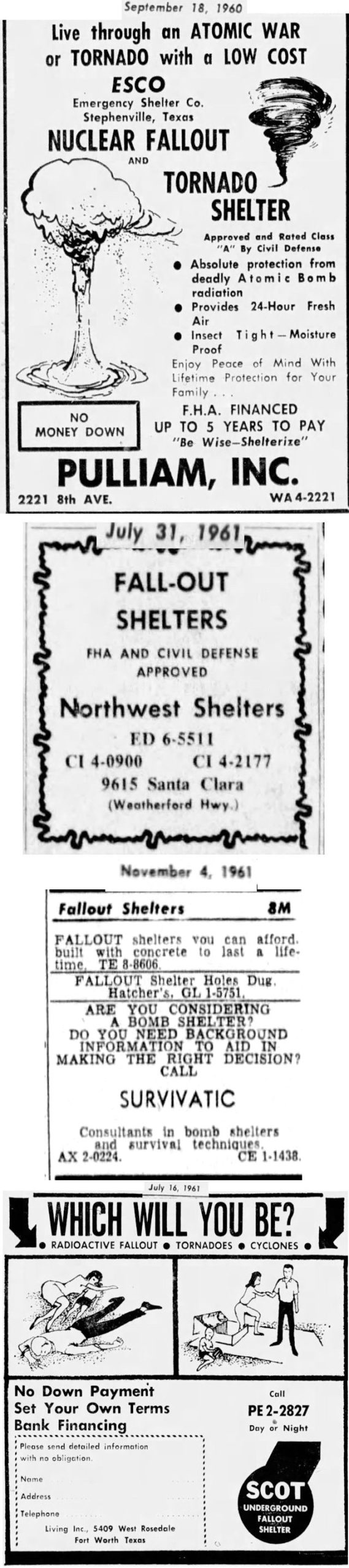

But soon Americans were worried enough to begin to act on that suggestion. The sales of fallout shelters, well, boomed.

But soon Americans were worried enough to begin to act on that suggestion. The sales of fallout shelters, well, boomed.

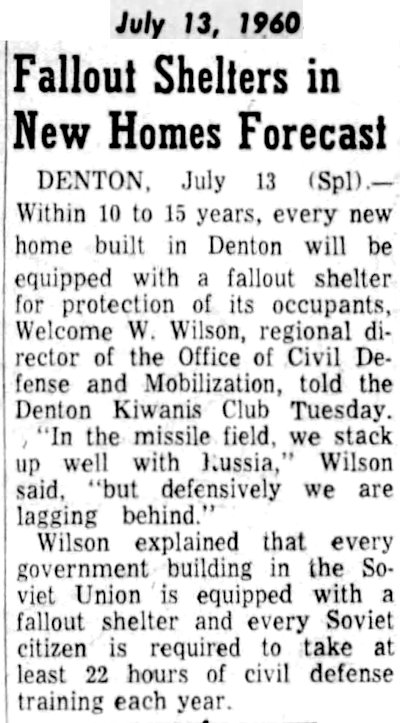

In fact, in July 1960 the regional director of the U.S. Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization predicted that within ten to fifteen years every home built in Denton would have a fallout shelter.

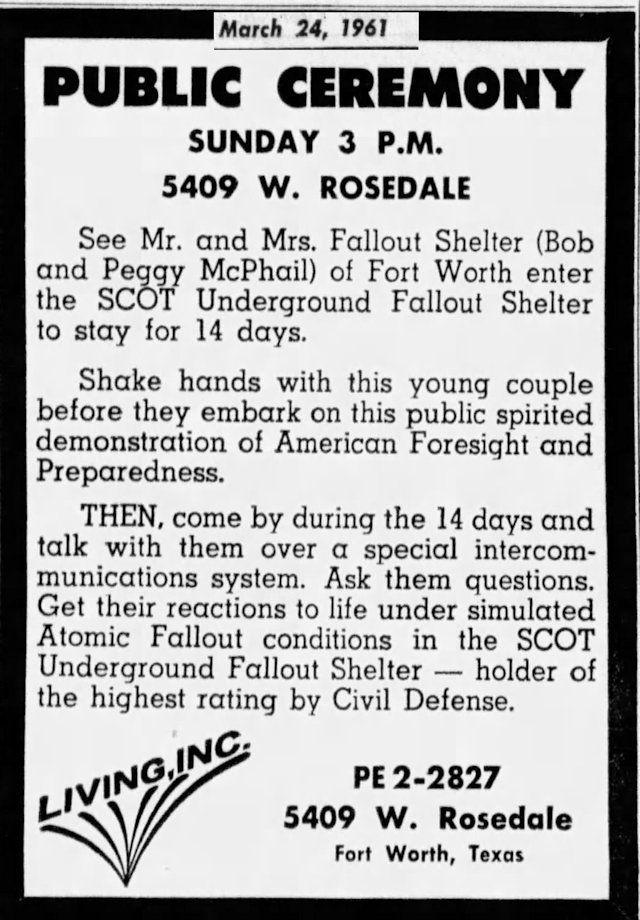

In 1960 ads for underground home fallout shelters began to appear in Fort Worth newspapers. The Star-Telegram added a new category in classified ads: fallout shelters. In the panel above, note that the bottom ad for Living Inc. was rather heavy handed.

In 1960 ads for underground home fallout shelters began to appear in Fort Worth newspapers. The Star-Telegram added a new category in classified ads: fallout shelters. In the panel above, note that the bottom ad for Living Inc. was rather heavy handed.

But as a sales promotion Living Inc. also held a contest to select a lucky couple to spend two rather public weeks living in a Living Inc. shelter. Bob and Peggy McPhail became “Mr. and Mrs. Fallout Shelter” of 1961.

But as a sales promotion Living Inc. also held a contest to select a lucky couple to spend two rather public weeks living in a Living Inc. shelter. Bob and Peggy McPhail became “Mr. and Mrs. Fallout Shelter” of 1961.

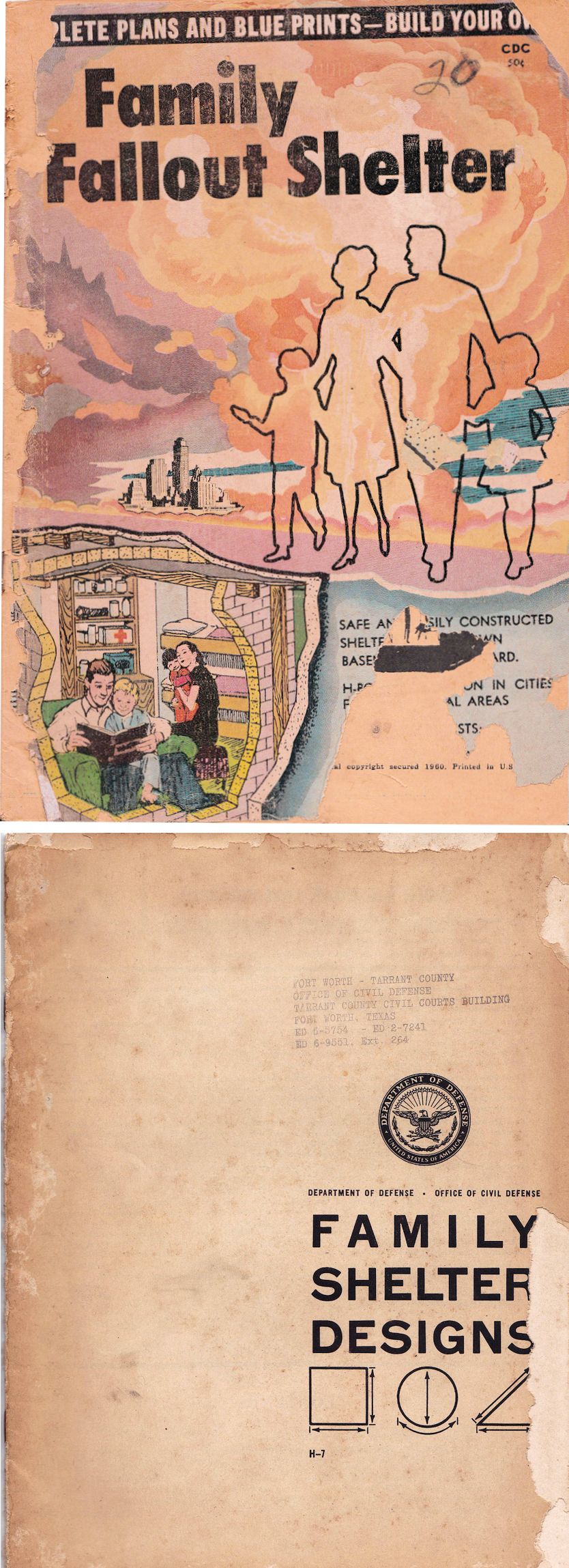

I still remember how frightened I was by the threat of nuclear war. Some guy on the other side of the world wanted to bury me! I begged my parents to build a fallout shelter. I collected pamphlets of plans like other kids collect comic books. (I still have these two, just in case Khrushchev’s grandson wants to bury me.)

I still remember how frightened I was by the threat of nuclear war. Some guy on the other side of the world wanted to bury me! I begged my parents to build a fallout shelter. I collected pamphlets of plans like other kids collect comic books. (I still have these two, just in case Khrushchev’s grandson wants to bury me.)

“Enough about add-on underground shelters, Hometown,” I hear you say. “Where was Fort Worth’s first built-in fallout shelter?”

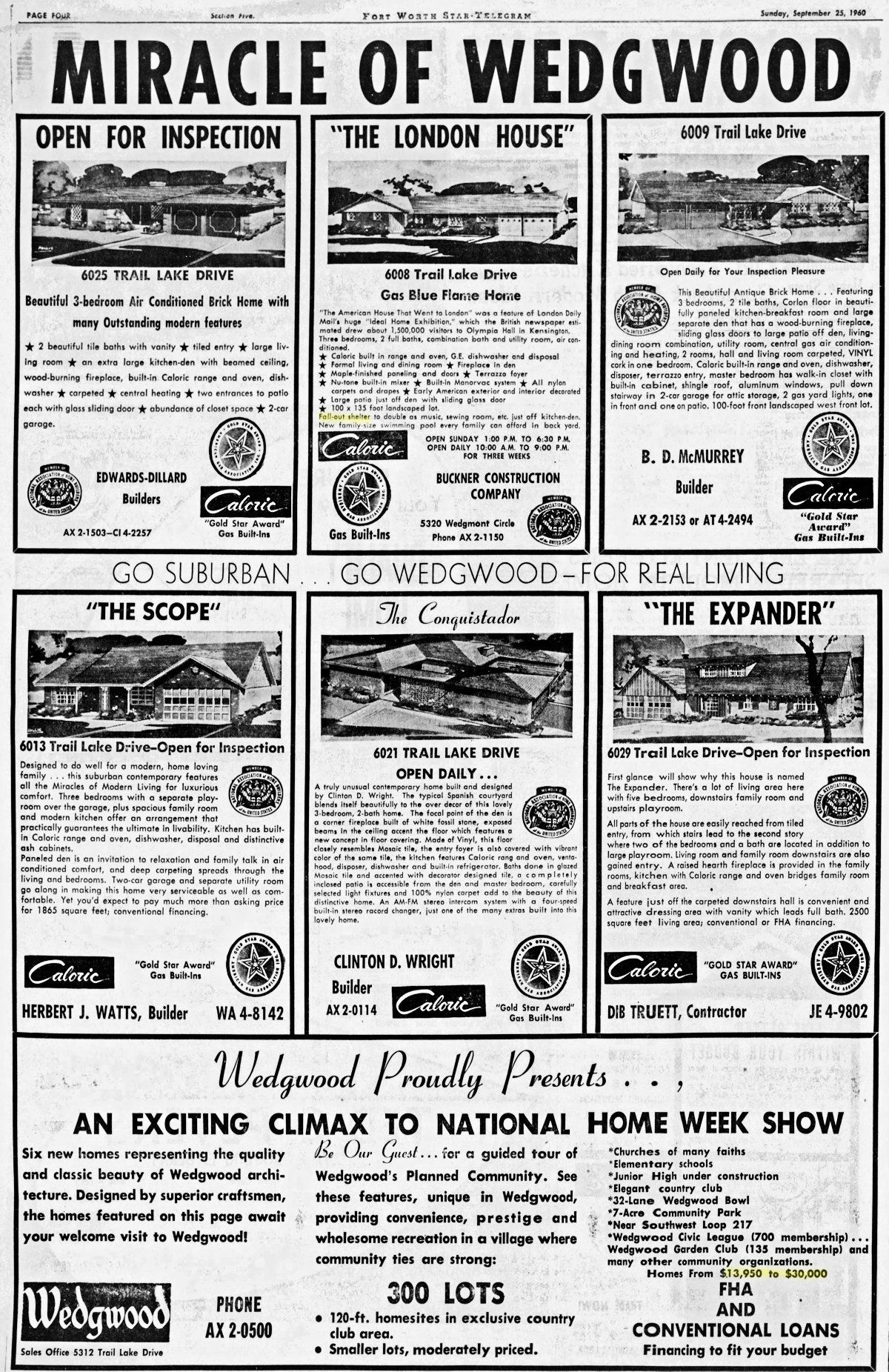

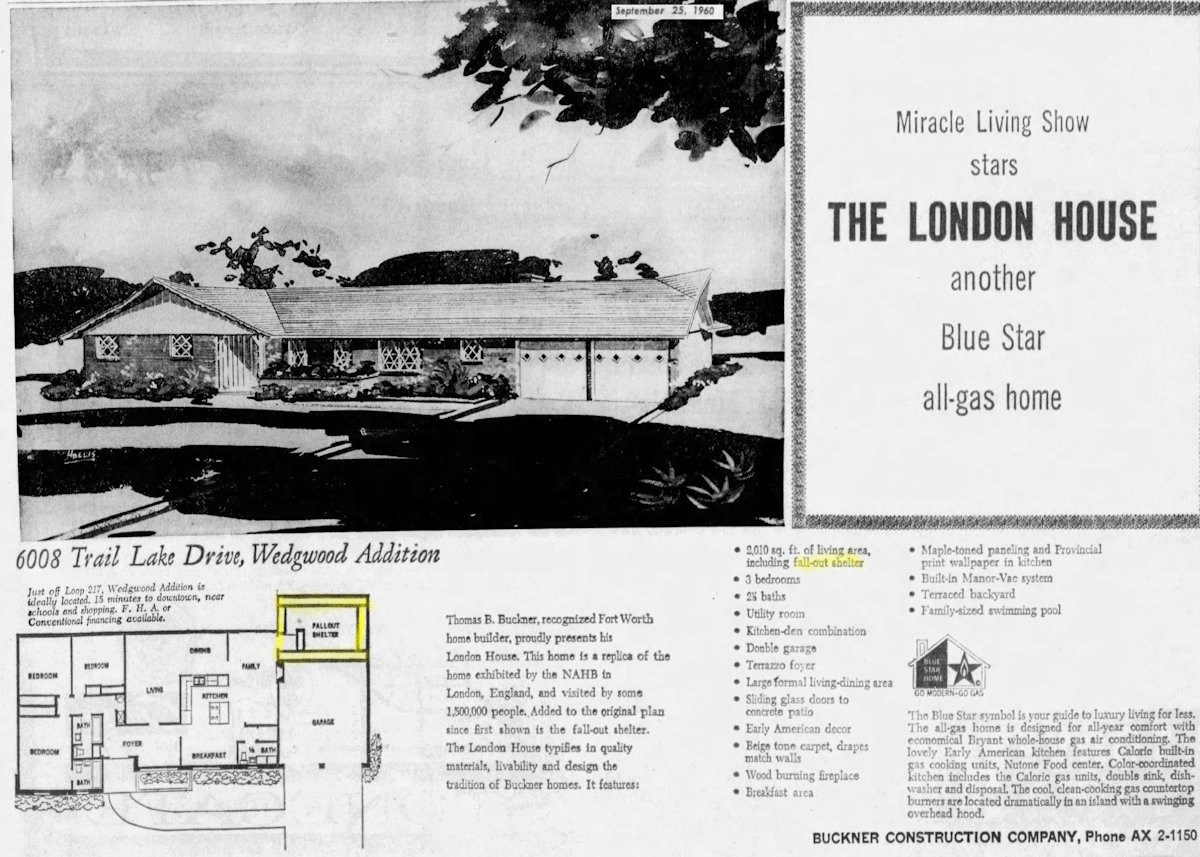

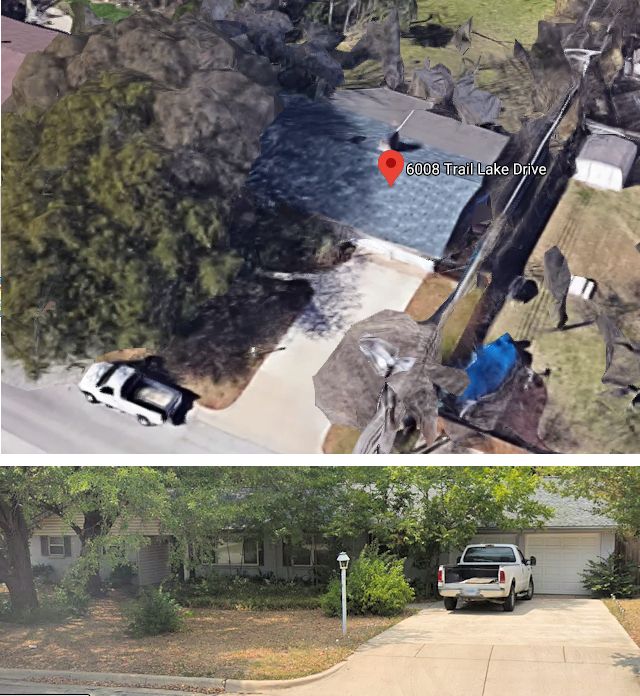

Glad you asked. According to WFAA-TV in September 1960, Fort Worth’s first built-in fallout shelter was in a new house at 6008 Trail Lake Drive in Wedgwood. (Film clip has no audio.)

It was an above-ground shelter stocked with food and water, emergency illumination, and games to keep the kiddos occupied during those long nights of nuclear winter.

(Twelve seconds into the film clip, on the right you can catch a glimpse of how sparsely developed Wedgwood was in 1960. The house was on Trail Lake Drive at Wedgmont Circle South. Wedgwood was still mostly open fields below Wedgmont Circle South.)

The house at 6008 Trail Lake Drive was featured in this full-page ad in September 1960.

The house at 6008 Trail Lake Drive was featured in this full-page ad in September 1960.

The floorplan shows the fallout shelter’s extra thick walls.

The floorplan shows the fallout shelter’s extra thick walls.

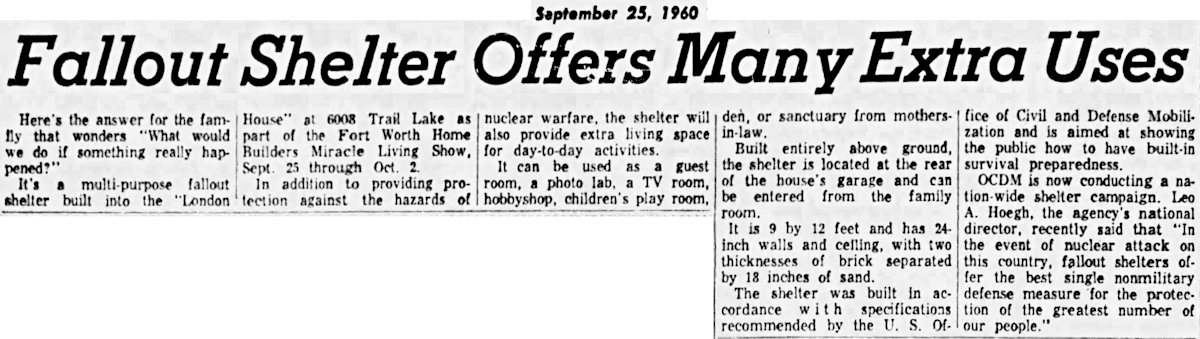

This text ad in the Star-Telegram pointed out that the fallout shelter “can be used as a guest room, a photo lab, a TV room, hobbyshop, children’s play room, den, or [ahem] sanctuary from mothers-in-law.

This text ad in the Star-Telegram pointed out that the fallout shelter “can be used as a guest room, a photo lab, a TV room, hobbyshop, children’s play room, den, or [ahem] sanctuary from mothers-in-law.

“Built entirely above ground, the shelter is located at the rear of the house’s garage and can be entered from the family room.

“It is 9 by 12 feet and has 24-inch walls and ceiling, with two thicknesses of brick separated by 18 inches of sand.

“The shelter was built in accordance with specifications recommended by the U.S. Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization and is aimed at showing the public how to have built-in survival preparedness.”

According to the OCDM, “in the event of nuclear attack on this country, fallout shelters offer the best single nonmilitary defense measure for the protection of the greatest number of our people.”

The house was called the “London House” because it was based on an American house that had been featured at a homebuilders show in London. The builder of the Trail Lake Drive house added the fallout shelter to the original plans.

The house was called the “London House” because it was based on an American house that had been featured at a homebuilders show in London. The builder of the Trail Lake Drive house added the fallout shelter to the original plans.

“Sliding glass doors lead out from the den into a large concrete patio and into a large terraced back yard, where the family may relax at poolside.”

Now that’s togetherness: sipping iced tea at poolside while scanning the sky for Soviet missiles.

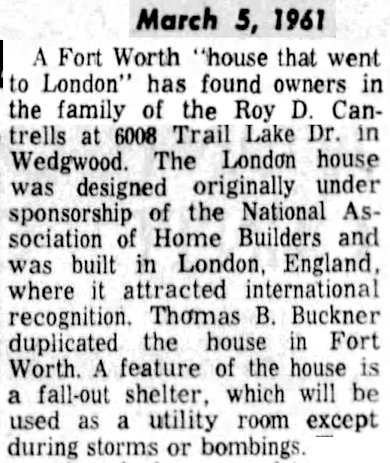

The first owner of the fallout house was Roy Cantrell in March 1961.

The first owner of the fallout house was Roy Cantrell in March 1961.

The house still stands.

The house still stands.

Fast-forward to October 1961. The Cantrells probably were thinking they bought the right house as the United States and Russia rattled sabers at each other during the Berlin Crisis. Fort Worth would be a prime target in a nuclear attack because of Carswell Air Force Base, a Strategic Air Command base. And right next door was another bull’s-eye: the bomber plant. And then there was the Nike missile base at Alvarado. Oh, the Ruskies had their eye on Cowtown, I was convinced. They probably monitored Slam Bang Theater with Icky Twerp to learn all about us.

Fast-forward to October 1961. The Cantrells probably were thinking they bought the right house as the United States and Russia rattled sabers at each other during the Berlin Crisis. Fort Worth would be a prime target in a nuclear attack because of Carswell Air Force Base, a Strategic Air Command base. And right next door was another bull’s-eye: the bomber plant. And then there was the Nike missile base at Alvarado. Oh, the Ruskies had their eye on Cowtown, I was convinced. They probably monitored Slam Bang Theater with Icky Twerp to learn all about us.

No doubt the Russians concluded that if they launched a nuclear attack on America, we’d retaliate by attacking Russia with really big cream pies.

No doubt the Russians concluded that if they launched a nuclear attack on America, we’d retaliate by attacking Russia with really big cream pies.

Fast-forward to October 1962. Another year, another October crisis, even though the month began unremarkably:

The Yankees had just won another World Series, beating the Giants. Prime-time TV shows included Route 66, 77 Sunset Strip, and Hawaiian Eye. Popular songs included “Monster Mash” and “Sherry.”

Gasoline was twenty-five cents ($2.14 today) a gallon.

Locally, current movies included Requiem for a Heavyweight at the Hollywood, If a Man Answers at the Worth, White Slave Ship at the Palace.

Overseas Motors would sell you a 1963 MG 1100 sedan for $1,895 ($16,000 today).

At Carlson’s on University Drive, a quarter of a chicken, a potato wedge, Texas toast, and honey would fill you up for fifty-seven cents ($4 today).

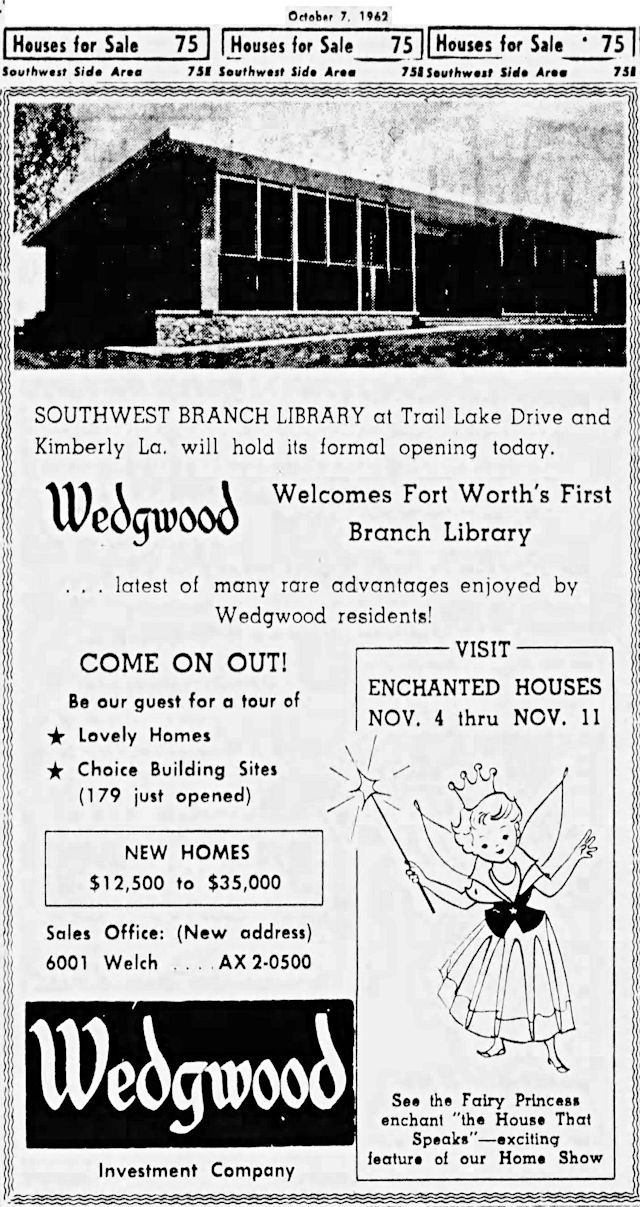

In October 1962 the city’s first branch library opened in still-developing Wedgwood, home of the fallout house. Houses in Wedgwood were selling for $12,500-$35,000 ($107,000-$300,000 today).

In October 1962 the city’s first branch library opened in still-developing Wedgwood, home of the fallout house. Houses in Wedgwood were selling for $12,500-$35,000 ($107,000-$300,000 today).

In October 1962 I had just started seventh grade at William James Junior High School. As I walked the halls of that strange new building with strange new classmates, I was aware of yet another transition:

During my six-year stretch at D. McRae Elementary School, my opinion of girls had started out low. On the “ick” scale, girls had fallen somewhere between cottage cheese and church.

But my opinion had steadily risen until by the time I entered junior high school in September 1962 girls no longer registered on the “ick” scale.

In fact, they were now on the “wow” scale.

And on the “wow” scale one girl in particular fell somewhere between cheeseburgers and Mickey Mantle.

She was in my seventh-grade world history class. A vision was she. Venus with braces. An adolescent Irene Adler. To me she would always be . . . “The Girl.”

I estimate that in history class that semester I stared at her—obliquely—from roughly the invention of the wheel through the Treaty of Versailles, now and then emitting an involuntary low moan, as if to dramatize the Battle of Waterloo or the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

As the second half of October 1962 began, I passed The Girl in the hall three days in a row. I remember her reaction as I dared to smile at her:

October 17: “Drop dead, creep.”

In her eyes I am naught but Kafka’s cockroach.

October 18: “Drop dead, creep.”

I should have been a pair of ragged claws scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

October 19: Silence.

She likes me!

Then came October 22 and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Remember?

Here are, in chronological order, Star-Telegram page 1 headlines of October 22-27, 1962:

Here are some details behind each day’s headlines:

Monday, October 22

The Star-Telegram announced that President Kennedy would address the nation concerning an “urgent matter” at 5 p.m. Kennedy also would meet with the National Security Council, his cabinet, and congressional leaders of both parties.

Tuesday, October 23

The Star-Telegram reported that Kennedy had ordered a naval blockade of Cuba, declaring that Russia was turning the island into a floating missile base capable of launching nuclear missiles to targets in the Western Hemisphere.

Those targets included me.

Excerpts from Kennedy’s address:

“Good evening, my fellow citizens. This government, as promised, has maintained the closest surveillance of the Soviet military build-up on the island of Cuba. Within the past week unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites is now in preparation on that imprisoned island. The purposes of these bases can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere. . . .

“I have directed that the following initial steps be taken immediately:

“First: To halt this offensive build-up, a strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated. All ships of any kind bound for Cuba from whatever nation or port will, if found to contain cargoes of offensive weapons, be turned back. . . .

“Our goal is not the victory of might but the vindication of right—not peace at the expense of freedom, but both peace and freedom, here in this hemisphere and, we hope, around the world. God willing, that goal will be achieved.”

Listen to Kennedy’s address.

Wednesday, October 24

The naval blockade began as twenty-five Soviet ships were sailing toward Cuba.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara said it was a “fair assumption” that at least some of the ships were carrying offensive weapons.

Thursday, October 25

United Nations Secretary General U Thant asked the United States to suspend its naval blockade and asked Russia to suspend its movement of ships to Cuba. U Thant urged a fourteen-day timeout by both sides to negotiate.

Friday, October 26

In Washington, the Star-Telegram wrote, tension was higher “than at any time since the Korean War.”

“High-level sources . . . warned that the current confrontation is a global one and not merely a bold Soviet move to determine U.S. resolution regarding Cuba.”

Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara said of the confrontation, “Direct aggression against Cuba would mean nuclear war. The Americans speak about such aggression as if they did not know or did not want to accept this fact. I have no doubt they would lose such a war.”

In fact, Fidel Castro was convinced that an American invasion of Cuba was at hand and on October 26 sent a telegram to Khrushchev that appeared to call for a pre-emptive nuclear strike on the United States.

Saturday, October 27

The Star-Telegram wrote: “The White House said Friday the Russian missile buildup in Cuba is continuing at a rapid pace, ‘apparently . . . directed at achieving full operational capability as soon as possible.’”

One indication of how angstful we Americans were: Radio stations WFAA and WBAP, which normally signed off at midnight, announced that they would remain on the air twenty-four hours a day “to give up-to-the-minute reports on the Cuban situation.”

The angst was contagious. Kids caught it from their parents. And from teachers. And from the anchors of the TV networks’ nightly newscasts.

“Gee, Walter Cronkite looks worried!” my parents said.

(Never mind that Walter Cronkite always looked worried!)

Suddenly it seemed that I, who had taken life for granted, had so much to live for.

I had been trying to talk my parents into letting me buy Barry Watts’s 1952 Cushman motorscooter, plying them with the usual practical points (“I could use it on my paper route,” “I could run errands for you with it”).

Of course, what I really wanted that scooter for was to impress . . . The Girl.

I pictured the two of us on that scooter, The Girl sitting behind me, as we putt-putted into the sunset.

Of course, that scooter was ten years old and had a motor of only five horsepower. The Girl would probably have to be content to just walk along beside me into the sunset.

She might even have to push.

Either way, nuclear annihilation would put a definite crimp in my social life.

Jeez, Mr. K, I’m only thirteen.

My parents, who suffered from the curse of literacy, subscribed to the morning and evening Star-Telegram and the Press. Thus, we saw the dire headlines three times a day.

In addition, I threw a Press route after school. Fifty or sixty times an afternoon I had to read the doomsday headlines as I pulled a tabloid-sized newspaper from my canvas bag, rolled it into a tube, and garroted the bad news with a rubber band.

Sunday, October 28

October 28, 1962 was one of those “I remember where I was when I heard” days (another such day would come thirteen months later).

The page 1 headlines, which had been dire all week, had become double-dog dire:

Fourteen thousand Air Force reservists were called up.

Fourteen thousand Air Force reservists were called up.

Unarmed U.S. reconnaissance planes flying over Cuba were fired upon from the island. A Soviet SA-2 surface-to-air missile shot down a U2, killing its pilot.

Kennedy said Khrushchev had offered to withdraw Soviet missiles from Cuba but then had withdrawn the offer to withdraw.

Senator Hubert Humphrey said Khrushchev planned to position thirty-three military divisions around Berlin in December and then announce that nuclear missiles in Cuba were aimed at American cities.

Castro offered to stop construction of military bases if the United States lifted the naval blockade. But the Star-Telegram wrote: “U.S. rejection of Castro’s offer seemed certain.”

The top photo shows antiaircraft rockets on a public beach in Key West, Florida—aimed at Cuba.

Locally, a woman told of being evacuated from the U.S. Navy base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where her husband was stationed.

She said, “If it takes his life to straighten this thing out, . . . that’s what he’s there for.”

I suspect that attendance at churches across America that Sunday night in October 1962 was SRO (suddenly religious overflow).

Me, I didn’t go to church that night, but I promised God that I’d start going if only he didn’t let Khrushchev bury me.

“Heck, Lord, I’ll go to church and eat cottage cheese. Lord, I’ll eat cottage cheese in church. Now I can’t be fairer than that, can I?”

As I went to bed that night I said farewell to my future—a future that until a week earlier had held the prospect of The Girl and Barry Watts’s motorscooter.

Now, I was convinced, I was going to die unkissed and unCushmaned.

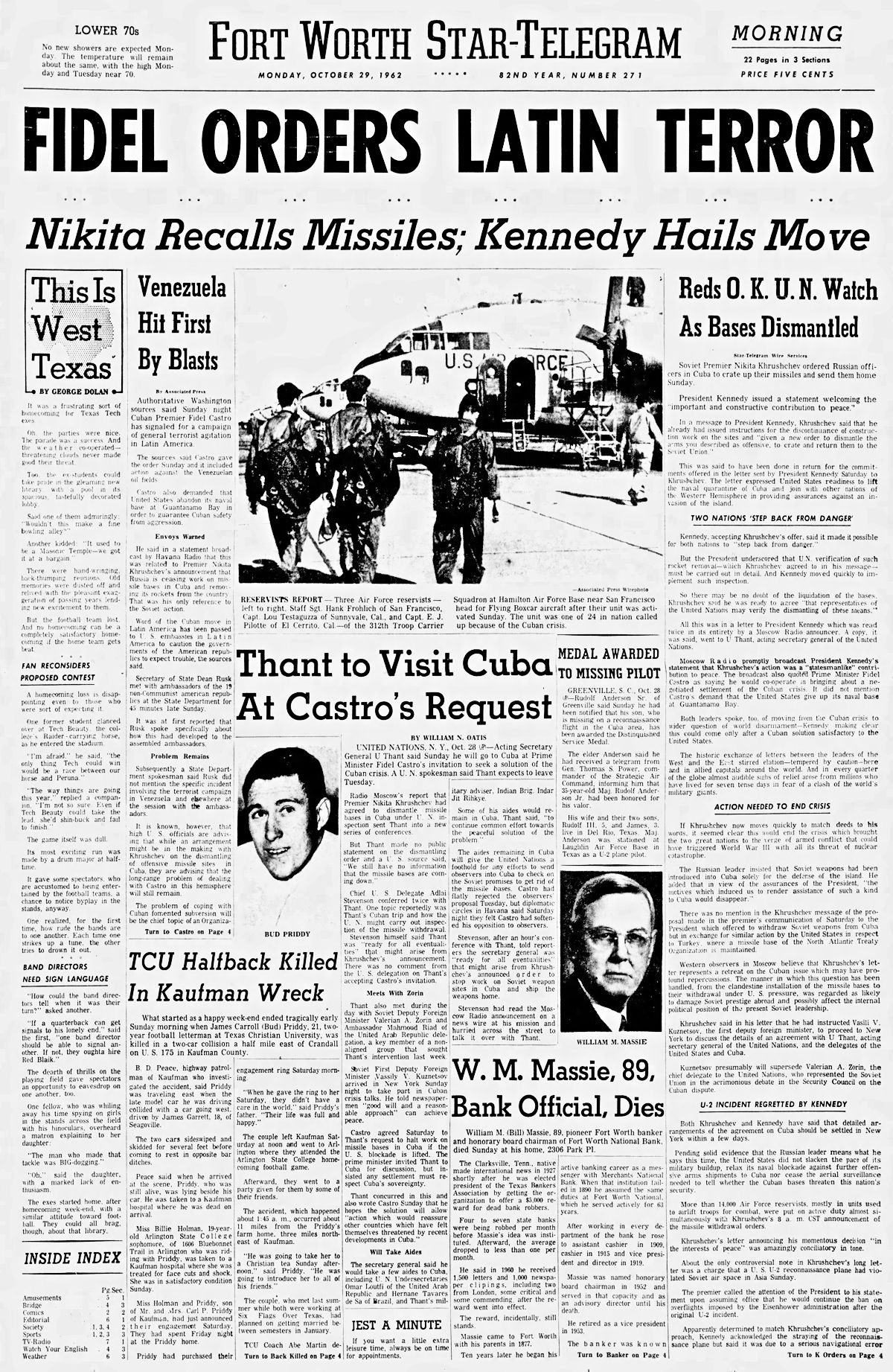

Monday, October 29

Needless to say, I was glad to wake up Monday morning and find that I was not 130 pounds of ashes and a pair of horseshoe taps.

And gladder still to see the front page of the morning Star-Telegram, which was on the porch before I got out of bed.

K had blinked.

K had blinked.

He had not buried me.

Across America the fever broke. The world exhaled. The sun came out from behind a mushroom cloud.

“Nikita Recalls Missiles,” “Reds O.K. U.N. Watch as Bases Dismantled.”

Wrote the Star-Telegram:

“Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev ordered Russian officers in Cuba to crate up their missiles and send them home Sunday.

“President Kennedy issued a statement welcoming the ‘important and constructive contribution to peace.’ In a message to President Kennedy, Khrushchev said that he already had issued instructions for the discontinuance of construction work on the sites and ‘given a new order to dismantle the arms you described as offensive, to crate and return them to the Soviet Union.’

“This was said to have been done in return for the commitments offered in the letter sent by President Kennedy Saturday to Khrushchev. The letter expressed United States readiness to lift the naval quarantine of Cuba and join with other nations of the Western Hemisphere in providing assurances against an invasion of the island.

“Kennedy, accepting Khrushchev’s offer, said it made it possible for both nations to ‘step back from danger.’

“So there may be no doubt of the liquidation of the bases, Khrushchev said he was ready to agree ‘that representatives of the United Nations may verify the dismantling of these means.’

“Moscow Radio promptly broadcast President Kennedy’s statement that Khrushchev’s action was a ‘statesmanlike’ contribution to peace. The broadcast also quoted Prime Minister Fidel Castro as saying he would cooperate in bringing about a negotiated settlement of the Cuban crisis.

“Both leaders spoke, too, of moving from the Cuban crisis to wider question of world disarmament.

“The historic exchange of letters between the leaders of the West and the East stirred elation—tempered by caution—here and in allied capitals around the world. And in every quarter of the globe almost audible sighs of relief arose from millions who have lived for seven tense days in fear of a clash of the world’s military giants.”

Later that morning I walked down the hall of William James Junior High. As I walked I fairly levitated with lightened step and buoyed heart. Then up ahead I saw . . . The Girl. She was walking toward me. The swaying of her ponytail, like a pendulum, was hypnotic. She was forty feet away . . . thirty . . . ten.

As we passed, I dared to look—obliquely—at her.

“Drop dead, creep.”

Life is back to normal!

(Thanks to Dennis Hogan for his help.)

Posts About Aviation and War in Fort Worth History

Pingback: Fights in Fort Worth when JFK was shot: “A white guy ... said ‘I’m glad he’s dead.’ ” - Technical Earn

My mom was so frightened during this time, she had a bomb shelter built in her back yard that absolutely ruined her yard, and while I had to work, she took my almost year old daughter to her parent’s house in Paducah, TX, where I’m sure there was no chance of a bomb hitting, but they did have a cellar! We had a tornado warning several years later and she wanted me to go down into it, told her I’d take my chances as it was really in bad shape!

Great example of the angst we lived through. thanks.

Good afternoon, sir. I loved everything about this article and found it very fascinating! I found it googling for pictures of my home in 1960’s. Turns out I’m the new owner of the “Fallout Shelter house”. I can attest that it’s still very much intact and has been well preserved. I would love to find any interior shots of the house during that time period.

Thank you. You own a piece of Cold War history! Everything I know about the house is in the post. A reader had tipped me off about the film footage, and I build the post out from that. I am delighted that you found the post.

In 1963 I was a senior at Paschal High. One of my best friends’ father decided they need a fallout shelter in their back yard. They lived in Wedgewood. He (the father) had his sons work every weekend digging a huge hole in the back yard big enough for the shelter he had ordered. Comes the big day the shelter is delivered and …………. it’s too big to fit between houses to get to the back yard! (No alleys between houses that backed up to each other.) He would have had to hire a crane to lift it over the house. So he sent the shelter back and for the next several weekends, the sons had to fill in the hole. I seem to remember that the dirt settled after some rain, so they made a fish pond out of it.

LOL! Great Cold War story. Thanks.