There is a story behind this street sign. And after you read the story you may never drive again down Evans Avenue without thinking of the Tobacco House Shootout, a slave woman’s curse, and, of course, Samuel Hemphill Evans.

There is a story behind this street sign. And after you read the story you may never drive again down Evans Avenue without thinking of the Tobacco House Shootout, a slave woman’s curse, and, of course, Samuel Hemphill Evans.

The story begins in 1829 in Garrard County in the bluegrass country of Kentucky. Two families—the Evanses and the Hills—were neighbors on Sugar Creek outside the town of Lancaster. Patriarchs of the two families were Hezekiah Evans, a physician, and John Hill, a blacksmith. One day Dr. Evans was abusing a female slave. He had recently been injured and was getting around on crutches. From astride his horse he hit the woman with a crutch, knocking her to the ground.

John Hill witnessed the abuse and ordered Evans to stop hitting the woman. Evans hit her again.

In response, the woman supposedly placed a curse on Dr. Evans. By one newspaper account she told him:

“Doctor Evans, you is a vi’lent man, en by you’ vi’lence you shall perish frum the earth. You’ family shall perish by vi’lence ’til they ain’t nary one left. Even you’ name’ll be pizen to them that hear it.”

Hill hit Evans on the head with his hickory stick, knocking Evans from his horse and putting him in bed for a few days.

Evans sued Hill for assault and battery but was awarded only “one cent and [court] costs.”

Was the curse already at work?

Living nearby on Sugar Creek was another Hill family headed by Jesse Hill. Not long after the hickory stick incident, Dr. Evans was appointed executor of the estate of Jesse Hill’s father. Jesse Hill accused Dr. Evans of defrauding the Hills in settling the estate.

Now each clan had a grudge to nurse.

Dr. Evans passed his grudge on to his children.

One of those children was Samuel Hemphill Evans, born in 1831. (Photo from DeGolyer Library, SMU.)

One of those children was Samuel Hemphill Evans, born in 1831. (Photo from DeGolyer Library, SMU.)

During Sam’s childhood the Evans-Hill feud flared frequently but nonfatally. Sam finished school at age fifteen and even taught school briefly.

Although the feud had begun with Dr. Evans and John Hill, Hill, like Evans, passed his grudge down to his children: The general of the Hill army was John Hill’s son Dr. Oliver Perry Hill.

Yes, each army was led by a physician.

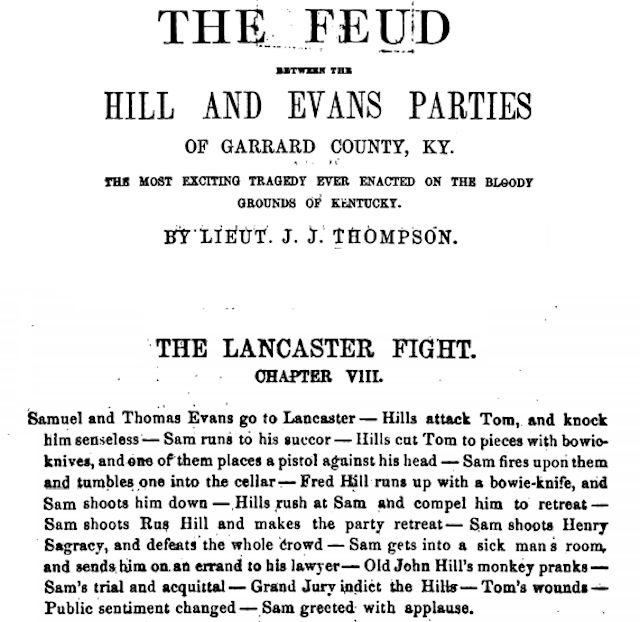

According to Lieutenant J. J. Thompson in A History of the Feud Between the Hill and Evans Parties (1854), among Dr. Hill’s lieutenants were sons Isaiah, Frederick, Rus, Jesse, William, and John. But Dr. Hill could enlist another forty blood kin, in-laws, and friends to feud with the Evanses. These men carried rifles, pistols, and Bowie knifes. This army’s rations usually included a jug of whiskey.

According to Lieutenant J. J. Thompson in A History of the Feud Between the Hill and Evans Parties (1854), among Dr. Hill’s lieutenants were sons Isaiah, Frederick, Rus, Jesse, William, and John. But Dr. Hill could enlist another forty blood kin, in-laws, and friends to feud with the Evanses. These men carried rifles, pistols, and Bowie knifes. This army’s rations usually included a jug of whiskey.

The Hills also were rock throwers, said to be as accurate chunking as shooting.

In 1849 Frederick Hill hosted a political barbecue at his home. The Evanses and Hills were observing an uneasy truce at the time, so Dr. Evans attended the barbecue. But as he was leaving, Jesse Hill and others of the clan began pelting Evans with rocks.

Thompson writes:

“When one would knock him in one direction, another would knock him as far the other way, in such a manner as to keep him vibrating like a pendulum.”

Dr. Evans was temporarily blinded.

“The Doctor, though yet blind, besought them to have mercy on him—but the more he begged, the harder and faster the pelting missiles flew.

“The Doctor was bruised perfectly black nearly all over, and his chest was very much swollen. His jawbone was broken in two places, and his head had not a few gashes. These wounds and bruises kept him in bed nearly two months, and so severe were they that the neighbors despaired of his recovery.”

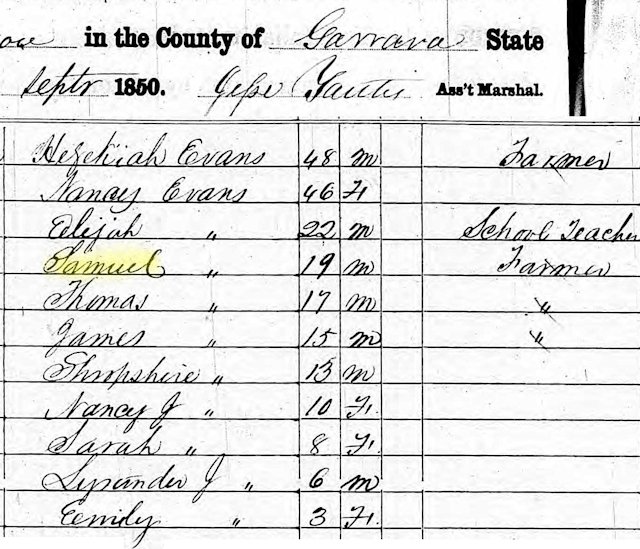

But Dr. Evans recovered and by 1850 had four sons of age fifteen or older: Elijah, Sam, Thomas, and James were old enough to become lieutenants in the Evans army and carry on the feud. Indeed, eventually Dr. Evans would raise his own army: fourteen children. Elijah did not participate in the feud. That left Sam Evans as the oldest lieutenant.

But Dr. Evans recovered and by 1850 had four sons of age fifteen or older: Elijah, Sam, Thomas, and James were old enough to become lieutenants in the Evans army and carry on the feud. Indeed, eventually Dr. Evans would raise his own army: fourteen children. Elijah did not participate in the feud. That left Sam Evans as the oldest lieutenant.

In March 1850 Dr. Evans went into Lancaster to attend court. Sam, nineteen, and another son, probably Thomas, seventeen, went with him.

Also in town were the Hills, drinking and lying in wait for unsuspecting Evanses.

Chief among the Hills present was Jesse.

As Dr. Evans went into the courthouse, he told Sam to stay outside and watch for Hills.

Meanwhile, Jesse Hill “went over to the tavern, took a glass of brandy, flourished his pistol in the air, and swore he would never take another drink of liquor till he had killed the Doctor or one of his sons.”

A neutral party warned Dr. Evans:

“Jesse Hill is out there ranting around; your little son is out there also. You had better go out and take care of him, he might get killed.”

“He is smart enough to take care of himself in any crowd, how small soever he may be.”

By one newspaper account, outside the courthouse “old Jesse Hill taunted young Sam Evans about the ‘negro woman’s curse.’ Sam immediately flared up, and harsh words flew. This had been expected, and Sam’s father had instructed his sons as to what they should do should the Hills carry the fight to them.”

Sam endured the taunting by Jesse Hill for some time before giving a prearranged signal.

At that signal Sam’s father came charging out of the courthouse with a pistol and shot Jesse Hill dead.

Dr. Evans and his sons fled town.

Dr. Evans, now in a position of having to fear both the law and the lawless, left the state.

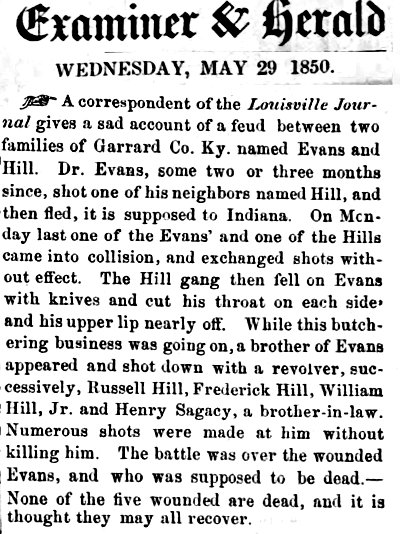

In May 1850, while Dr. Evans was still in exile, sons Sam and Thomas went into Lancaster for supplies.

In May 1850, while Dr. Evans was still in exile, sons Sam and Thomas went into Lancaster for supplies.

Of course, they were attacked by the Hill clan: brothers Frederick, Isaiah, Rus, and William and brother-in-law Henry Sagracy. While Sam was in a shop, Thomas was struck by bullets and rocks and knocked senseless on a sidewalk. Sam heard the ruckus and ran to his brother. By the time Sam reached Thomas, the Hills were cutting Thomas with Bowie knives.

Thompson writes:

“Just as Sam arrived . . . he saw one of the party run up to Tom and put a pistol against his head. At that instant Sam fired, struck the fellow in the right shoulder, and tumbled him, together with his pistol, into a cellar. The next moment Fred[erick] Hill ran up with a Bowie knife, and was about to plunge it into Tom’s breast, when Sam drove a ball into his back, and stretched him on the ground. Isaiah Hill attempted to pull Tom a little from the wall that he might have fairer hacking. Sam fired at his breast and struck the handle of a pistol in the right side of his coat, which so frightened him that he ran away.

“The crowd before the door was placed there to shoot Sam as he came down, while the others were to do the work for Tom. At the last shot, Sam’s pistol ceased to revolve, being impeded by the fragment of an exploded cap. As soon as those before the door saw this, they rushed at him, and ran up the stairs with upraised Bowie knives, ready for a butchery. He retreated up the stairs, and by this time succeeded in getting his pistol to revolve, Rus Hill was in front, and when Sam pointed the pistol at him, he turned, tucked down his head, and ran back, receiving the ball in his right shoulder. . . . Sam dropped the revolver on the floor, drew two single barrels, and with one in each hand, ran down to his former stand. When he got down, he saw Henry Sagracy leveling a pistol at him. At that instant Sam threw up his pistol. Sagracy wheeled and received the ball in his right shoulder.”

Sam also grazed William Hill.

“The Hills, after they ran away from Sam’s empty pistol, went over to Yantis’s drug store and got their rifles, where they had previously deposited them. They then returned and searched for Sam and would have put an end to Tom’s suffering had they not been prevented. The citizens then interposed and carried away the wounded to the different taverns.

“The squad placed in front of the door to shoot Sam fired about thirty balls at him, but not a single one touched even his clothes—they lodged in the door facings and in the ceiling of the shop. This is an extraordinary fact, for it can scarcely be conceived how every one of such a shower of balls could miss him. Some people believe that the balls did hit him but that he had on a shield or breastplate, which preserved him unwounded. To this I cannot answer; but the fact of his clothes not being touched, is evidence enough that the balls would not have harmed him notwithstanding the shield. Sam thought, and said, that they were only snapping [pulling the trigger on unloaded guns] at him; but one of the party replied to this report, ‘Whoever said that, told a d-n lie, for I shot at him six times myself.’”

The score: The Hills had wounded one Evans; Sam Evans had wounded three Hills and a Sagracy.

The Hills, who had attacked Sam and Thomas, swore out a writ against Sam, swearing that he had instigated the violence.

Sam was tried and acquitted.

The Hills were not charged with any crime.

Thomas Evans recovered from multiple knife wounds.

After this confrontation Dr. Evans returned to Garrard County, where he was still wanted for killing Jesse Hill. A grand jury—you guessed it—declined to indict Evans.

Indeed, in most cases participants in the Evans-Hill feud served jail time only while they were awaiting trial for assault or murder. In most cases they were acquitted. Through it all residents of Garrard County for the most part walked around corpses on the sidewalk, crossed the street to avoid gunfights, and went indoors when knives began to fly, embracing an “It’s got nothing to do with me” attitude.

Fast-forward to January 1852. Dr. Evans rode from home to visit a patient. He again took Sam along. On their homeward trip they were ambushed by Rus Hill. The two Evanses and Hill exchanged gunfire.

Rus Hill, Thompson writes, “was swearing at a wicked rate”:

“‘I can whip a hundred and ninety-nine Evanses—I am beeswax and rawsum (rosin); by G-d—I can whip all h-ll!’”

As the shooting continued, Sam asked his father:

“‘Are you hurt?’

“‘I am not hurt. Shoot that scoundrel, don’t you see how he keeps on shooting at us?’ replied the Doctor, composedly.

“Sam dashed up to Hill and fired—Hill returned the fire.”

Hill dismounted and hid behind a log to continue shooting.

Dr. Evans said to Sam:

“‘Get off that horse, for you cannot manage him. Quit shooting that little revolver, take my large pistols and kill the dog [Rus Hill]!’

“Sam handed his father the bridle, took the pistols, and started toward Hill.

“Sam . . . marched directly toward Hill, under a heavy and steady fire. When he got about halfway, Sam pulled trigger, but snapped—he pulled away again and took a clump of hair and skin from the top of Hill’s head.

“As they were exchanging empty for loaded pistols, Hill fired at them, then wheeled, and ran off leading his horse. Sam gave chase, but Hill soon sprang upon his horse and galloped off.

“There was no damage done on either side, save the minus portion of Hill’s head.”

Native Americans were not the only fighters who took the scalps of enemies.

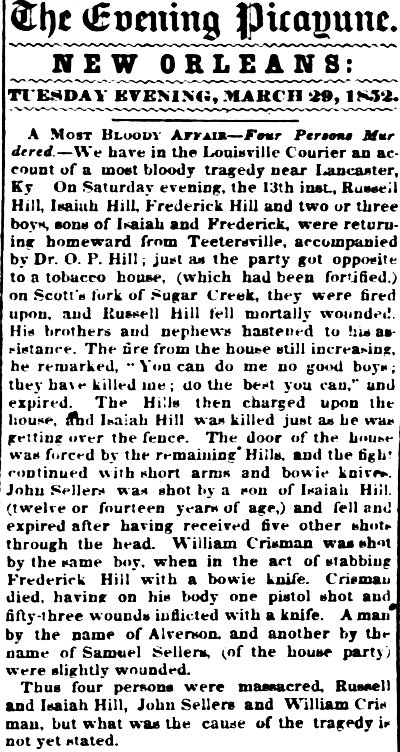

In March 1852 two allies of the Evanses—John Sellars and William Chrisman—were tired of being menaced by the Hill clan. They went to Dr. Evans and begged him to give them enough guns to finish off the Hills and end the feud.

Dr. Evans refused to give them guns, but he did offer them the services of his top lieutenant: “If the fight must come up, get Sam to help you—you and he can whip them in any situation.”

But for whatever reason, Sam Evans was not present soon after at the deadliest confrontation of the Evans-Hill feud.

A road ran alongside Sugar Creek. The farm of Dr. Evans bordered the road. On his farm was a tobacco house about sixty yards from the road.

On March 13, 1852 Dr. Oliver Perry Hill, Rus Hill, Frederick Hill (at whose barbecue Dr. Evans had been beaten), and Jesse Jr. (son of the man whom Dr. Evans had killed) were helping a relative move his family and furniture from Isaiah Hill’s farm.

As they traveled the road they were heavily armed because they had to pass the Evans farm.

Unbeknownst to them, four men were in the Evans tobacco house: brothers John and Sam Sellars, William Chrisman, and James Alverson. They had seen the Hill convoy pass on its outbound trip and had proceeded to fortify the tobacco house and add gun ports in time for the Hills’ inbound trip.

As the Hill convoy neared, the men in the tobacco house began firing. John Sellars hit and killed Rus Hill.

Dr. Hill ordered his men to charge the tobacco house. John Sellars hit and killed Isaiah Hill. Sellars then ran out of the tobacco house and took cover behind a large tobacco barrel. He fired several times at Jesse Hill Jr. but without effect. The boy returned fire. One ball from his pistol struck a stave of the barrel, and the splinters struck Sellars in the eyes. Blinded, he ran, and Jesse Hill Jr. shot him between the shoulders, killing him.

William Chrisman was still in the tobacco house as Frederick Hill charged. A ball from Chrisman’s pistol took a lock of hair from the top of Hill’s head, but Hill charged on. Chrisman grabbed a Bowie knife to attack Hill. But the knife fell from his hand, and Hill grabbed the knife and killed Chrisman.

Thompson writes of the aftermath:

“Jack May [an Evans ally] rode up to the Doctor’s [Evans] in great haste and excitement and told him that Sellars and the Hills were fighting—that the Hills, about twenty strong, had besieged Sellars and Chrisman in the tobacco house and were shooting at them as fast as they could load.

“Upon the reception of this intelligence, the Doctor told his sons to get their rifles and run over to assist Sellars. But when they arrived, the battle had terminated, the Hills were all gone.”

Four men had been killed in the Tobacco House Shootout. A fifth later died of his wounds.

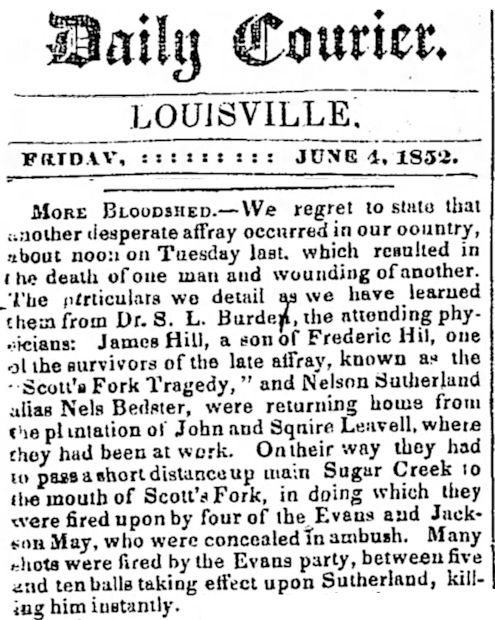

Fast-forward to June 1. Sam and Thomas Evans were returning home from a trip to Lancaster. Near the scene of the Tobacco House Shootout, the brothers encountered James Hill and Nelson Sutherland (also known as “Bedster”).

Fast-forward to June 1. Sam and Thomas Evans were returning home from a trip to Lancaster. Near the scene of the Tobacco House Shootout, the brothers encountered James Hill and Nelson Sutherland (also known as “Bedster”).

Another day, another gunfight.

Thompson writes:

“The [Evans] boys saw them [Hill and Sutherland/Bedster] first, about sixty yards distant, and as Bedster was a few paces before Hill, they raised their guns and fired upon him. Bedster raised his gun and was in the act of shooting when the balls struck him, causing him to wheel, run about a hundred yards and fail. Jim Hill leaped into a deep ravine beside the road and fired at them with a double-barrel shotgun, then wheeled and ran back toward the creek. They gave him a hot chase for about three hundred yards, and shot him in the hip, which brought him to the ground. They shot him again through the thigh as he fell and would have killed him, but his supplications for mercy stayed the bloodthirsty dagger. They were more than anxious to kill him, but his prayers for mercy touched their hearts with compassion.

“When Bedster [Sutherland] fell, he had a rifle, a Colt’s large repeater, two single-barrel pistols, and a very large Bowie knife. The pistols and knife were worn in a belt, in regular land-pirate fashion. Upon examination, Dr. Hill said that four rifle balls passed through his [Sutherland’s] heart, several went into his neck, and others struck the gun stock.”

The (remaining) members of the Hill clan swore out a warrant and had Sam and Thomas arrested.

James Hill recovered from his wounds.

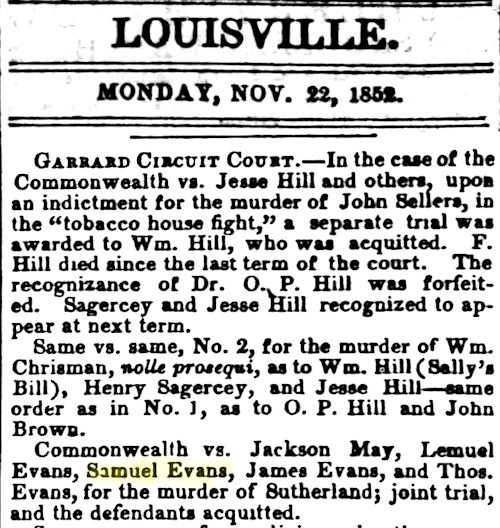

In November 1852 Sam and Thomas Evans went on trial for the killing of Nelson Sutherland.

In November 1852 Sam and Thomas Evans went on trial for the killing of Nelson Sutherland.

Thompson writes:

“The boys had their trial at the sitting of the November court. Before the trial came up, the Hill party and friends made a violent effort to adjourn the court, reporting that cholera had broken out very malignantly in town. But in spite of this effort the court continued.”

At trial it was shown that Dr. Hill had hired mercenaries from nearby Washington County to reinforce his bullet-riddled army. Sutherland had been one of those mercenaries.

“During the trial it was proven that Bedster [Sutherland] had been hired to fight at fifteen dollars [$500 today] per month, with an extra pay of five dollars [$160] for every scalp taken from the Evans party.”

Sam and Thomas were acquitted.

Soon after that trial, the feud began to wane. It had raged more than twenty years. One half of the slave woman’s curse (“You’ family shall perish by vi’lence”) of 1829 had not come true: According to Thompson, at least ten Hills were killed but not one Evans.

Why did the feud wane? For one thing, several of the enemy had been killed, leaving fewer targets. Also participants on both sides began to move away. Eventually there was no one around to shoot at.

Two of the Hills—James and Jesse Jr.—moved away.

So did Dr. Oliver Perry Hill. He moved to Oregon and lay low for two years. After his return he continued to practice medicine. He died in 1891—of natural causes.

His obituary includes nary a word about the Evans-Hill feud.

Dr. Hezekiah Evans also moved away. After an assassination attempt in 1855 he went to Mexico.

Dr. Evans returned to Garrard County, where in 1862 the other half of the slave woman’s curse (“by you’ vi’lence you shall perish”) did come true: Dr. Evans was shot to death near his home, possibly by a Union soldier.

Two of Dr. Evans’s sons—Sam and Thomas—also moved away.

And stayed away.

Sam and Thomas moved to Texas in 1853.

Sam’s first job in Texas?

Deputy sheriff.

Sam: From the Bluegrass Killing Fields to Evans Avenue (Part 2)

Fort Worth’s Street Gang

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

Feudin’ footnote:

In December 1865 Lieutenant James J. Thompson of Noxubee, Mississippi, author of A History of the Feud Between the Hill and Evans Parties, was organizing a colony in Brazil, recruiting southerners who did not want to live under Yankee reconstruction. Thompson was planning to ship his father’s cotton crop to Brazil. The father discovered his son’s plan and refused to allow it. Thompson in a rage shot his father and killed his stepmother and her three children. A mob broke Thompson out of jail that night and hanged him.