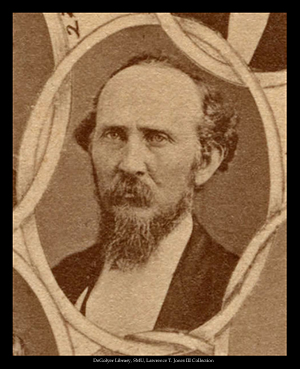

By 1853 Samuel Hemphill Evans, one of fourteen children of Dr. Hezekiah and Sarah Evans of Garrard County, Kentucky, was ready for a change. Like his brothers, Sam had fought in and survived the Evans-Hill feud (see Part 1) that raged more than twenty years and that killed, by one count, ten Hills and wounded several Evanses.

By 1853 Samuel Hemphill Evans, one of fourteen children of Dr. Hezekiah and Sarah Evans of Garrard County, Kentucky, was ready for a change. Like his brothers, Sam had fought in and survived the Evans-Hill feud (see Part 1) that raged more than twenty years and that killed, by one count, ten Hills and wounded several Evanses.

Evans moved to Robertson County, Texas, where he served for three months as a deputy sheriff.

Evans moved to Robertson County, Texas, where he served for three months as a deputy sheriff.

From there he went to Brownsville, where he bought a herd of ponies and drove them to Tarrant County. He bought a tract of land here and settled down just as the Army was abandoning its Fort Worth. (Photo from DeGolyer Library, SMU.)

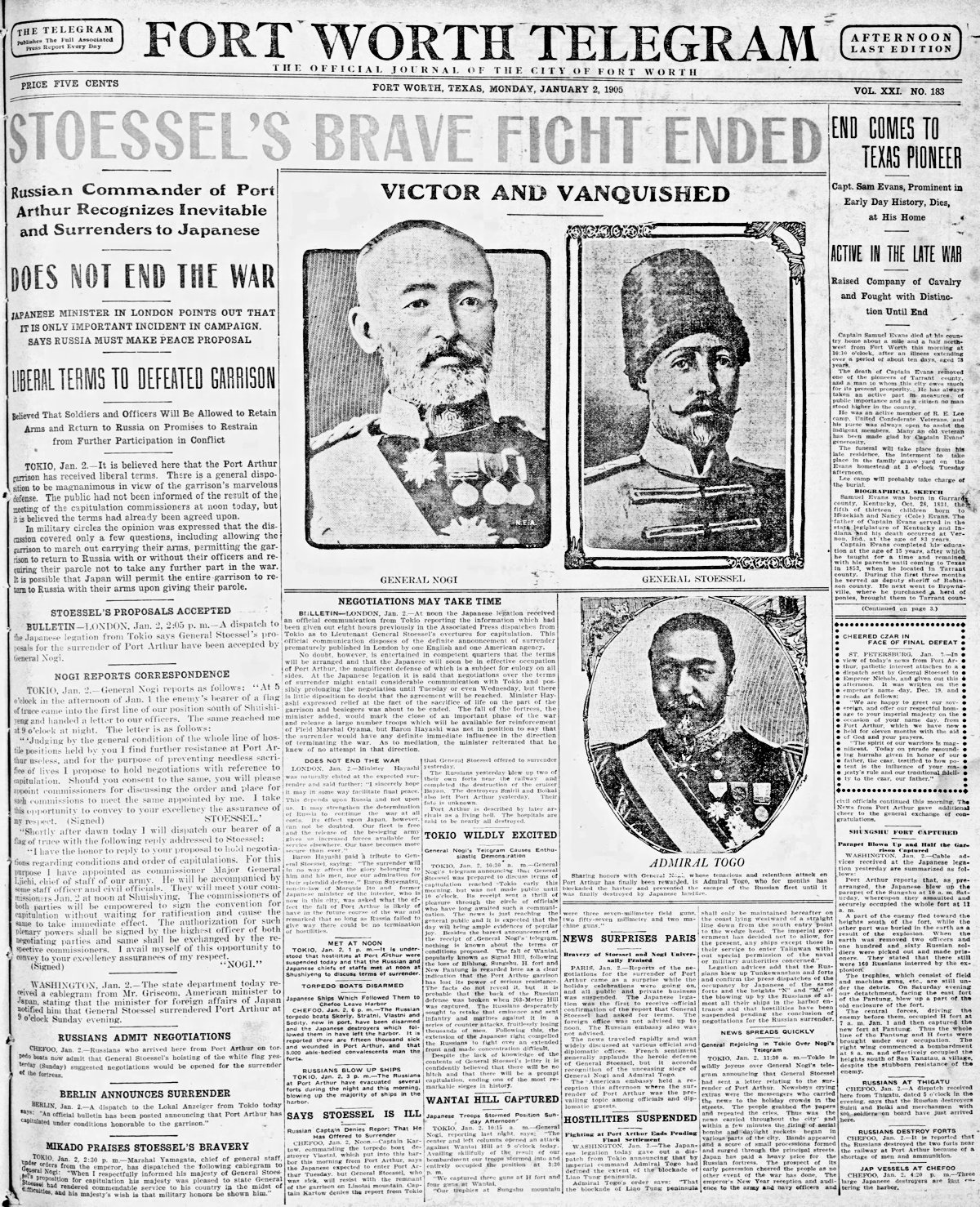

According to the Fort Worth Telegram, “In the year of 1853, when the Witherspoon family was massacred by Indians, Captain Evans organized a company of sixteen men and followed the Indians to Twin Mountains [Young County], where a fight took place; also in Erath County, at Ball Mountain, at the head of Stroud’s Creek [Hood County], and in Palo Pinto County. Here darkness over took his company, and the Indians made their escape. In the attack a number of men were killed, two men and several horses were wounded, but the company succeeded in getting nine scalps.”

When Evans came to this area, most everything was being done for the first time. Evans claimed that he was the first person to buy and sell cattle in Tarrant County, the first to drive cattle from here to Kansas on the Chisholm Trail. He claimed that he was the first man to take a cargo of buffalo hides from here to New Orleans, the first to drive a herd of sheep from here to New Orleans.

He also traded cotton between Tarrant County and New Orleans and Galveston.

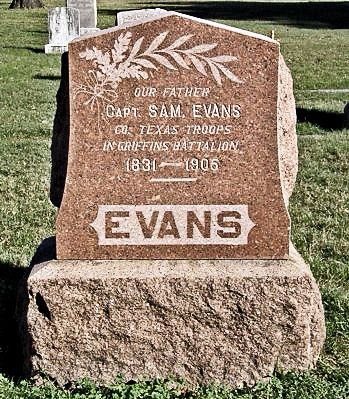

When the Civil War began in 1861, Evans, after surviving the Evans-Hill feud, must have thought “been there, done that.” Nonetheless, he enlisted. He organized and drilled a troop of cavalry here and later organized a company of infantry for Griffin’s Infantry Battalion, which served in the Trans-Mississippi Department along the Texas coast. He was at Galveston in command of a company at the time of the capture of the Union steamer Harriet Lane in 1863. From Galveston he took his command to Sabine Pass after Confederate Major Richard Dowlin’s lopsided victory there when the Union tried to invade Texas in November 1863. In November 1864 Griffin’s Infantry Battalion merged into the 21st Texas Infantry Regiment. Evans was back in Galveston at the time of surrender.

After the war Evans entered local politics. He served in the state House in 1866 and in the state Senate from 1870 to 1873.

Evans was a bit of a contradiction. He was a politician but distrusted government. He was an outspoken advocate of Fort Worth’s economic growth but opposed some of the very factors that drove that growth: banks, corporations. He felt that corporations hurt farmers and small businesses. And despite helping bring the first railroads to Fort Worth, he opposed the railroads as an industry.

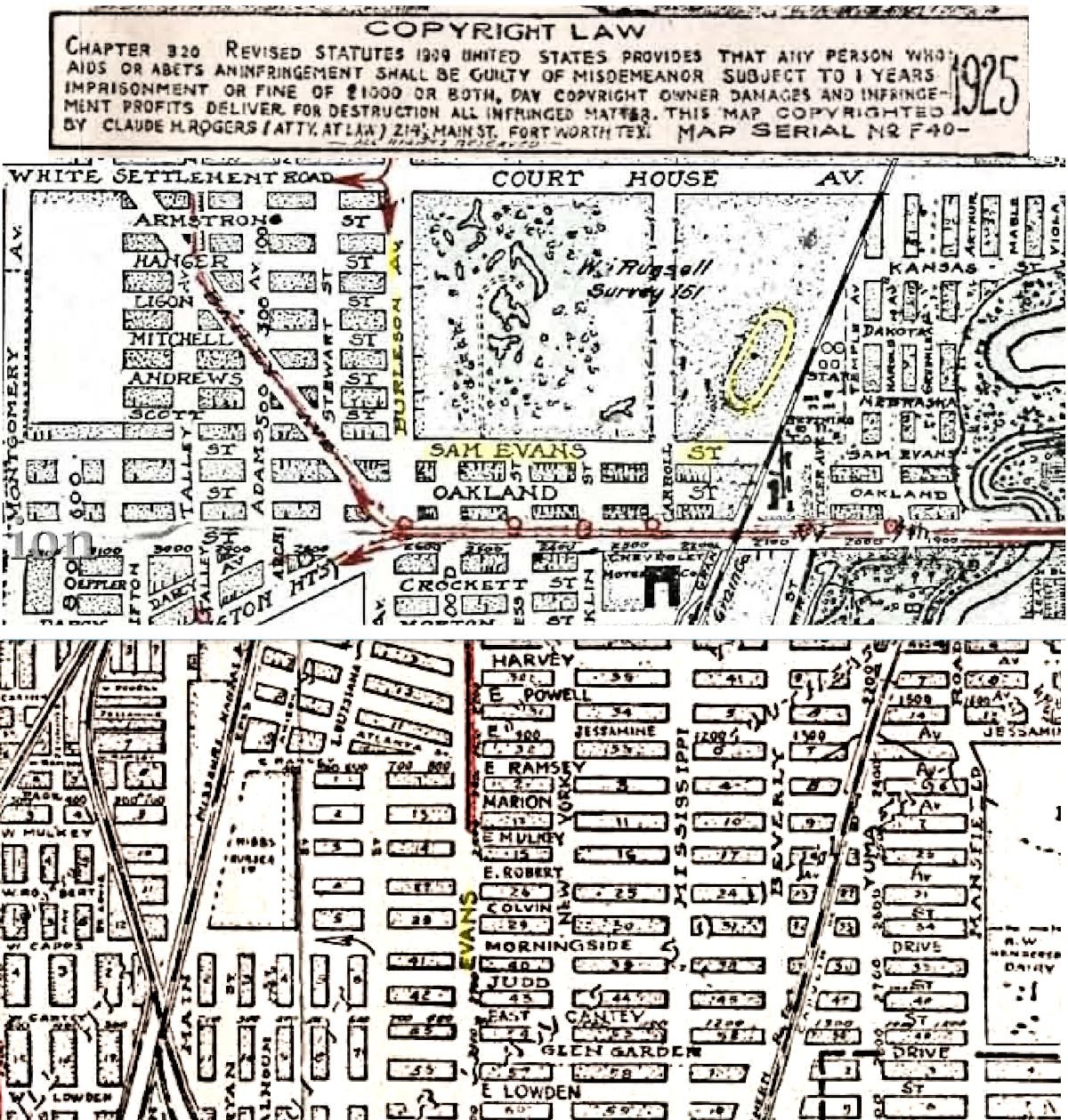

In 1871 Evans bought farm a mile and a half west of the courthouse and just north of today’s White Settlement Road (hashed line). Note the “Powder House” on the left.

In 1871 Evans bought farm a mile and a half west of the courthouse and just north of today’s White Settlement Road (hashed line). Note the “Powder House” on the left.

That year Evans also helped Fort Worth get its first permanent newspaper. Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt in his autobiography Force Without Fanfare writes: “John Hanna, Captain Sam Evans, W. H. Overton, Junior W. Smith, and I felt that having a newspaper was imperative as a means of letting our light shine and publicizing to Texas, as well as the rest of the world, that Fort Worth was on the map. Major J. J. Jarvis had discontinued his newspaper at Quitman, and I wrote him to ascertain whether he would sell us his old Washington press. He replied that he would. A group of us went in together and bought a wagonload of wheat, which we sent to Major Jarvis to pay for the press. Thus, in 1871 the Fort Worth Democrat was started.”

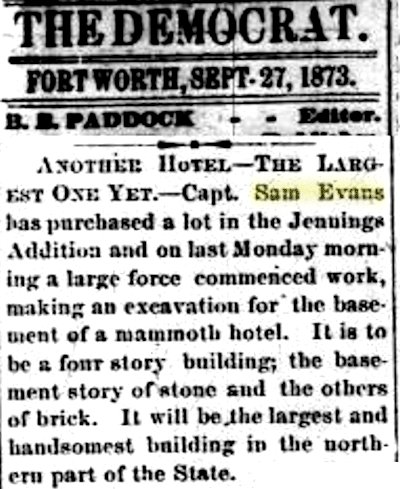

Evans farmed his homestead, but he also bought and sold land on all sides of town. In 1873 he built a hotel in the Jennings addition, which was being developed at the time in the southwest corner of downtown.

Evans farmed his homestead, but he also bought and sold land on all sides of town. In 1873 he built a hotel in the Jennings addition, which was being developed at the time in the southwest corner of downtown.

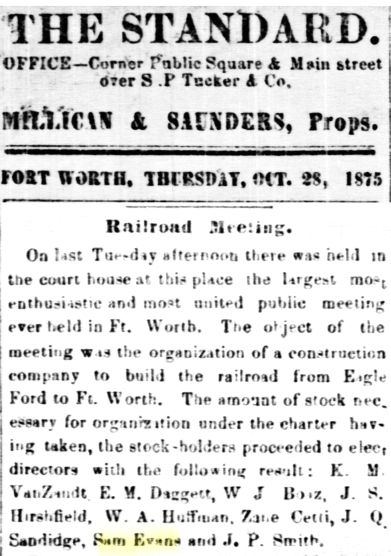

Despite his opposition to the railroad industry, in 1875 Evans was one of the men—such as Ephraim Merrell Daggett, William J. Boaz, John Hirshfield, Walter Huffman, Jesse Zane-Cetti, and John Peter Smith—who in 1875 formed the Tarrant County Construction Company to lay track from Eagle Ford to Fort Worth for the Texas & Pacific railroad.

Despite his opposition to the railroad industry, in 1875 Evans was one of the men—such as Ephraim Merrell Daggett, William J. Boaz, John Hirshfield, Walter Huffman, Jesse Zane-Cetti, and John Peter Smith—who in 1875 formed the Tarrant County Construction Company to lay track from Eagle Ford to Fort Worth for the Texas & Pacific railroad.

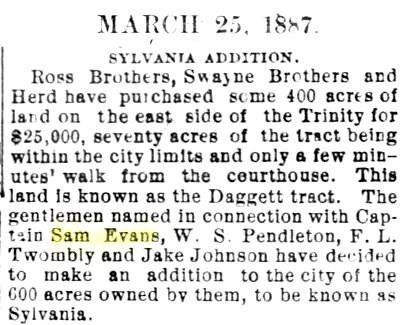

In 1887 Evans, gambler Jake Johnson, and future disgraced mayor William S. Pendleton announced that they would develop six hundred acres east of the river as the Sylvania addition.

In 1887 Evans, gambler Jake Johnson, and future disgraced mayor William S. Pendleton announced that they would develop six hundred acres east of the river as the Sylvania addition.

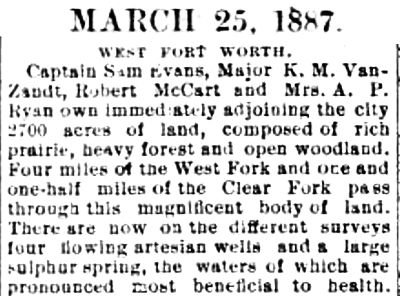

In 1887 the Gazette reported that Evans, along with Van Zandt, Robert McCart, and Mrs. A. P. Ryan, owned 2,700 acres west of town. These people, along with William J. Bailey and the Edwards family, owned most of the West Side over the years.

In 1887 the Gazette reported that Evans, along with Van Zandt, Robert McCart, and Mrs. A. P. Ryan, owned 2,700 acres west of town. These people, along with William J. Bailey and the Edwards family, owned most of the West Side over the years.

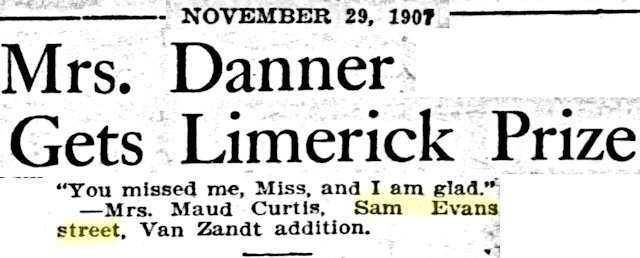

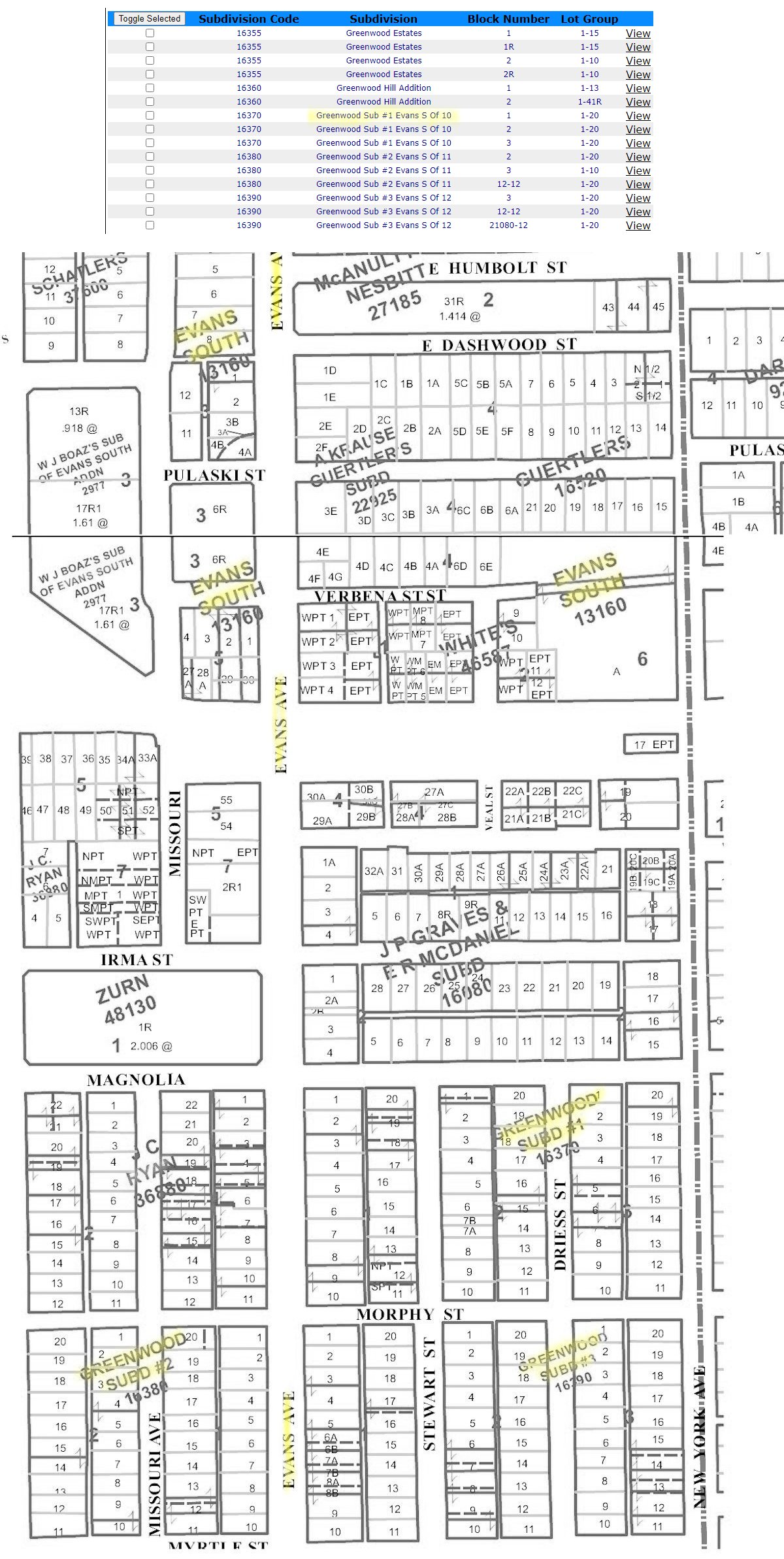

By at least 1907 Sam Evans was a member of Fort Worth’s street gang: He had a street named for him.

By at least 1907 Sam Evans was a member of Fort Worth’s street gang: He had a street named for him.

“Where was that street, Hometown?” I hear you ask.

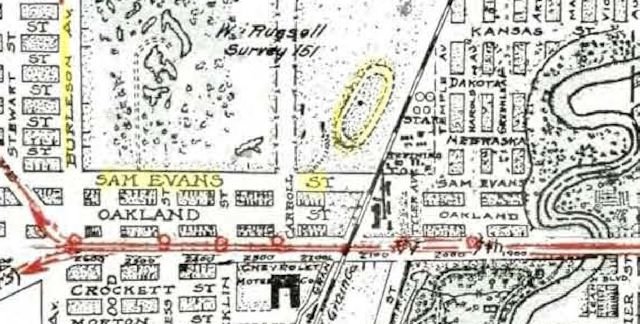

It was today’s West 5th Street just two blocks north of West 7th Street. But Evans’s home was a half-mile north of West 5th. I suspect that he—or his heirs—at one time owned all the land in between, including the future site of the driving park (oval) and Montgomery Ward. On this 1925 map note that University Drive was “Burleson Avenue.”

It was today’s West 5th Street just two blocks north of West 7th Street. But Evans’s home was a half-mile north of West 5th. I suspect that he—or his heirs—at one time owned all the land in between, including the future site of the driving park (oval) and Montgomery Ward. On this 1925 map note that University Drive was “Burleson Avenue.”

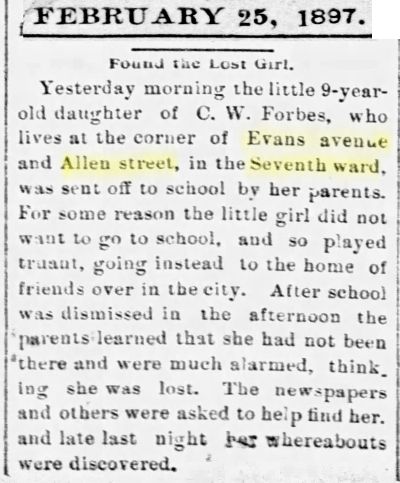

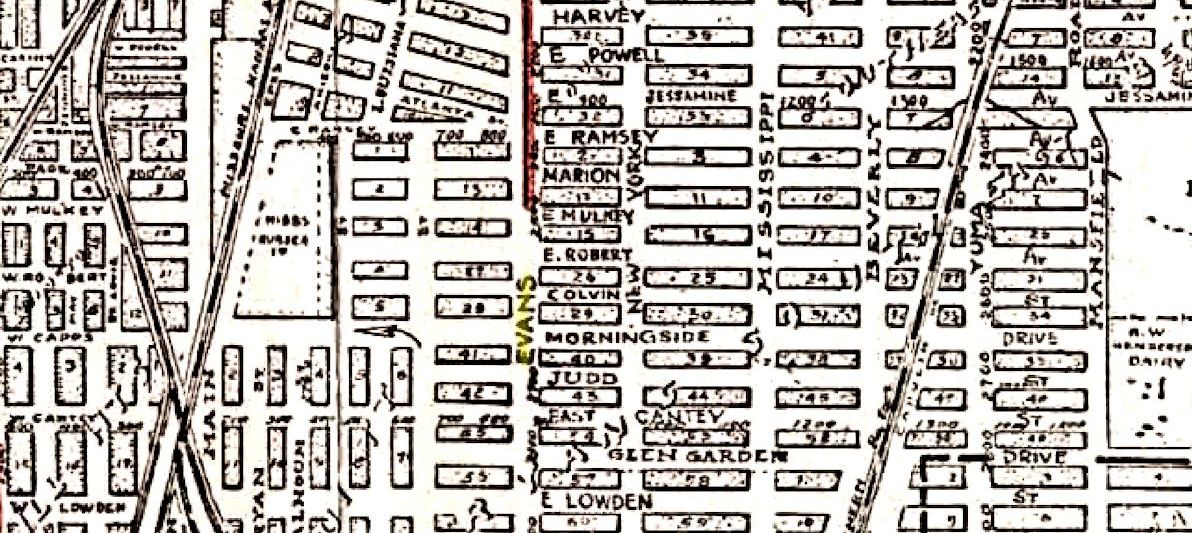

And as early as 1897 there was a second street named for Sam Evans: Evans Avenue in the Seventh Ward southeast of downtown.

And as early as 1897 there was a second street named for Sam Evans: Evans Avenue in the Seventh Ward southeast of downtown.

“Hold on, Hometown,” I hear you say. “I’ll concede that Sam Evans Street was named for Sam Evans. But how do we know that Evans Avenue is named for Sam Evans and not some other Evans?”

“Hold on, Hometown,” I hear you say. “I’ll concede that Sam Evans Street was named for Sam Evans. But how do we know that Evans Avenue is named for Sam Evans and not some other Evans?”

A good question and one that requires some digging to answer.

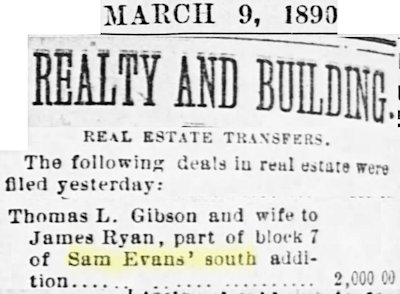

I discovered that as early as 1890 Sam Evans had developed his Sam Evans South addition. But where is it located? Newspaper real estate transfer lists give only lot, block, and addition, not street.

I discovered that as early as 1890 Sam Evans had developed his Sam Evans South addition. But where is it located? Newspaper real estate transfer lists give only lot, block, and addition, not street.

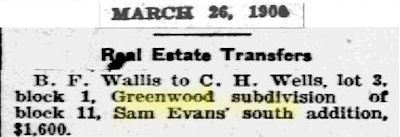

And when you search the deed cards and maps of Tarrant Appraisal District, you find several additions named “Evans” and even “Evans South.” Close, but no cigar.

Where is the “Sam” that would connect the dots?

Here is a transfer that gives us a clue: Greenwood is a subdivision of Sam Evans South addition.

Here is a transfer that gives us a clue: Greenwood is a subdivision of Sam Evans South addition.

That gives us another keyword to try.

Sure enough, a search of TAD’s database turns up a Greenwood subdivision of “Evans South”—no “Sam.” Ah, but the previous clip shows us that Greenwood is a subdivision of Sam Evans South. Ergo, Evans South and Sam Evans South are one and the same. Don’t ask me why TAD dropped the “Sam.”

Sure enough, a search of TAD’s database turns up a Greenwood subdivision of “Evans South”—no “Sam.” Ah, but the previous clip shows us that Greenwood is a subdivision of Sam Evans South. Ergo, Evans South and Sam Evans South are one and the same. Don’t ask me why TAD dropped the “Sam.”

And the central street of Sam Evans South addition is . . . Evans Avenue.

Even as late as 1925 Sam Evans still had two streets named after him.

Even as late as 1925 Sam Evans still had two streets named after him.

In the 1870s Evans became disenchanted with the political status quo. He rejected both of the major parties and joined the Greenback Party. In 1877 he was the only Texas delegate at the party’s convention in Memphis. The Greenback Party opposed gold and favored paper money, contending that eastern bankers controlled gold and impoverished small farmers.

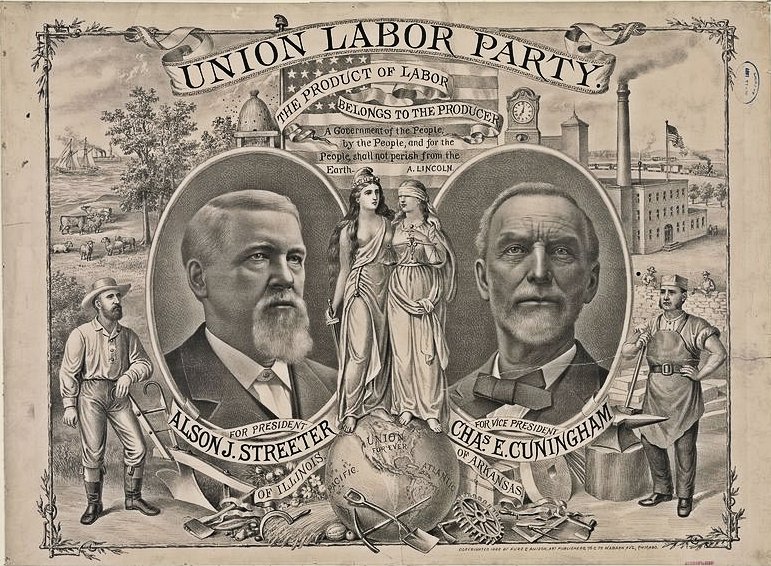

Evans eventually left the Greenback Party for an offshoot, the Union Labor Party, which appealed to farmers and urban laborers and fielded candidates for the 1888 presidential election. In fact, the ULP nominated Evans for vice president, but he declined. He was replaced by Charles E. Cunningham. In the national election the ULP ticket received only 150,000 votes and carried only two counties in the country.

Evans eventually left the Greenback Party for an offshoot, the Union Labor Party, which appealed to farmers and urban laborers and fielded candidates for the 1888 presidential election. In fact, the ULP nominated Evans for vice president, but he declined. He was replaced by Charles E. Cunningham. In the national election the ULP ticket received only 150,000 votes and carried only two counties in the country.

Eventually Evans left the Union Labor Party for the Populist Party, which was anti-business, anti-banks, anti-railroads anti-Catholic, and anti-immigrant.

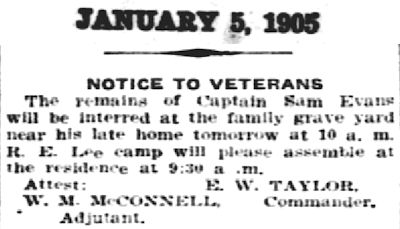

Sam Evans may be been “anti” a lot of things, but he was staunchly pro-Confederacy. Evans, like Van Zandt, Captain J. C. Terrell, and Judge C. C. Cummings, was one of the organizers of the Robert E. Lee Camp, the local branch of United Confederate Veterans.

Sam Evans may be been “anti” a lot of things, but he was staunchly pro-Confederacy. Evans, like Van Zandt, Captain J. C. Terrell, and Judge C. C. Cummings, was one of the organizers of the Robert E. Lee Camp, the local branch of United Confederate Veterans.

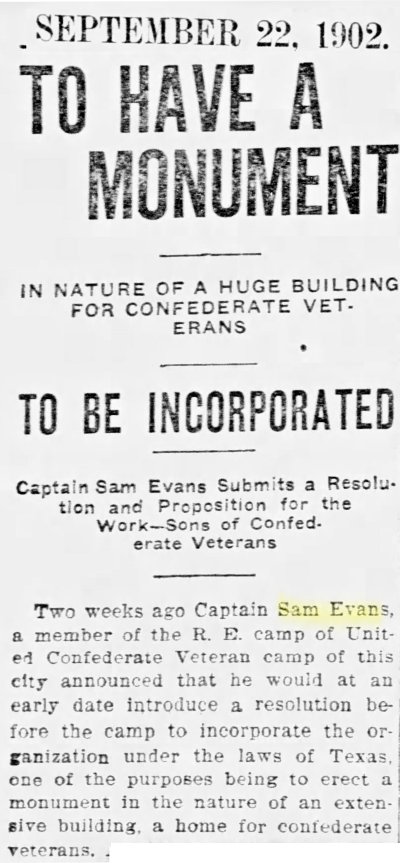

In 1902 Evans proposed incorporation of the local branch in order to build a home for Confederate veterans.

Like many Confederate veterans, Evans continued to believe that the Lost Cause—which espoused the antebellum southern way of life (including white supremacy)—was noble and just.

Evans’s resolution proposing incorporation begins with a statement that conveys the prejudice of many Confederate veterans:

“Whereas, this camp, in wisdom, has been organized for social and charitable purposes, and for the further purpose of honoring the name of R. E. Lee, the greatest military genius the world has ever produced, the man who, with less than 600,000 unarmed men, without money, without a navy, without recognition as a government by the world, without discipline, united in a common cause for the purpose of maintaining the supremacy of the white man, . . .”

Evans described the proposed veterans home, apparently without irony, as “a monument that will unite the Caucasian race North, South, East and West in brotherly love and a language that can be spoken and understood from pole to pole; a monument without prejudice, sparkling with bright gems of integrity, justice, equality and love of humanity.”

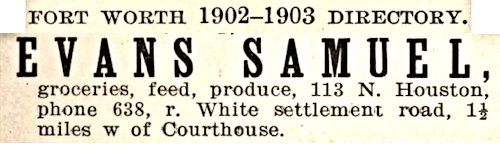

At the end of his life the old Kentucky feuder operated a grocery store on the courthouse square where the first Leonard’s Department Store would later be.

At the end of his life the old Kentucky feuder operated a grocery store on the courthouse square where the first Leonard’s Department Store would later be.

Samuel Hemphill Evans died on January 2, 1905. His estate was valued at $150,000 ($4.3 million today). Not bad for a grocer.

Samuel Hemphill Evans died on January 2, 1905. His estate was valued at $150,000 ($4.3 million today). Not bad for a grocer.

At age seventy-three Evans was proud of the fact that he had never smoked, drank, danced, or attended church.

His obituary, like that of Dr. Oliver Perry Hill (see Part 1), includes nary a word about the Evans-Hill feud.

His funeral, as was the custom of the day, was held at his home. He was memorialized by members of the R. E. Lee Camp.

Samuel Hemphill Evans—who survived a bloody feud, Native American fights, and the Civil War and had two streets named after him—was buried in the family cemetery on his old homestead.

As his old homestead was parceled off, he was reburied in Greenwood Cemetery under a new tombstone.

As his old homestead was parceled off, he was reburied in Greenwood Cemetery under a new tombstone.