If you explore Fort Worth’s cemeteries from dawn to dusk you won’t find many inhabitants who were born earlier than Gustavus Adolphus Everts: 1797.

In 1797 John Adams had just been sworn in as the second president of the United States. Napoleon was just a general in the French army. Beethoven had not yet composed his first symphony. The U.S. flag had fifteen stars. The “Star-Spangled Banner” was seventeen years in the future.

Everts was born in the Northwest Territory (today’s Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota). His father was a surveyor of public lands in the territory.

After his father died, his mother educated Everts and her other seven children.

The 1877 Fort Worth city directory includes an autobiographical profile written by Everts. He wrote:

“My mother was a fine scholar, had had every advantage that means and position could give under the guidance of Dr. Wheelock, president of Dartmouth College, and she taught me to read. She instructed me in English grammar, arithmetic, and geography, so that in the spring of 1812 I entered the Ohio University.”

In 1816 Everts was married in Ohio (which had become a state in 1803).

Everts writes: “In 1818 I went to Kentucky, taught a seminary four or five years, and read law all my leisure time, and in December 1823 was licensed to practice law.”

In 1828 he moved to Indiana. In 1832 fourteen Native Americans owed $20,000 to Ann Burnet, niece of David G. Burnet, interim president of the Republic of Texas. Guerom S. Hubbard, a fur trader to whom Ann Burnet was betrothed, finagled possession of the note from her and had the Native Americans jailed in Chicago.

The Native Americans hired Everts to defend them.

“I started from Fort Wayne [Indiana] with a U.S. interpreter and about forty Indians, all well armed. There were but two trading points on the way, one at South Bend, on the Calumet River, near its mouth on Lake Michigan. There were but three or four houses in Chicago besides the fort, called Dearborn. The case was called. I had my answer ready; my defense was fraud in procuring the assignment [of the note] from Ann Burnet; a fraudulent and villainous intent to collect the money and appropriate it to his [Hubbard’s] own use; his breach of marriage contract, for he was married in New York.”

The jury found for the defendants.

Everts recalled that Pokagan, the orator of the tribe, declared that the “Indians would pay all due on the note. The Indians in a treaty in November following gave to me for my fee and loss of a horse the sum of $500 in cash and a section of land.”

The Native Americans also paid off the note as promised.

The Fort Worth Gazette wrote of Everts: “In the early days of his practice during the troubles between the Indians and whites he was employed to defend an Indian who had killed a white main. This he did successfully for the man was acquitted. After that he was highly respected by the Indians, and when the Indians were asked to cede to the whites that country now comprising a part of western Illinois, before they would take any action they sent for him and took his advice.”

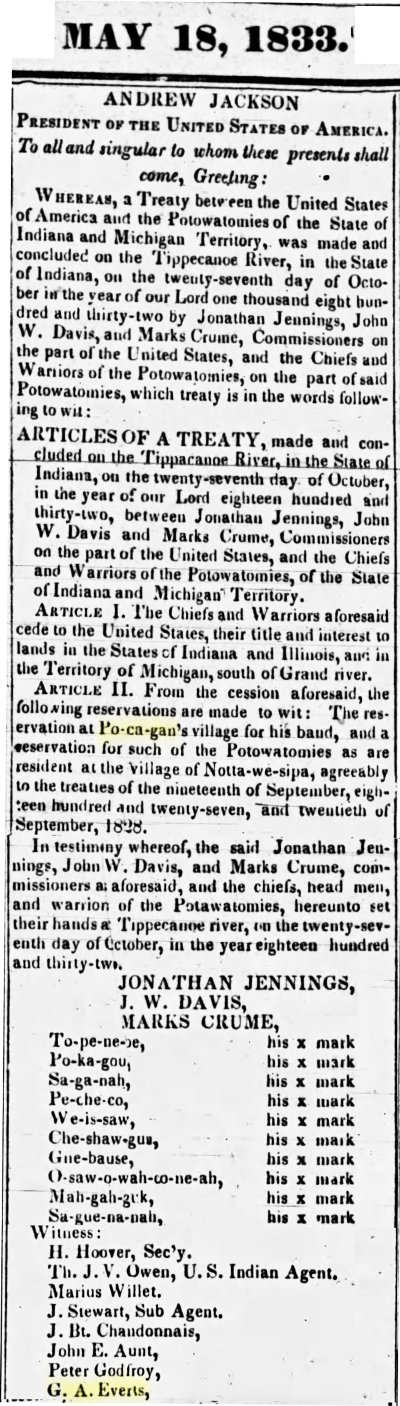

In 1833 the Kentucky Gazette printed this treaty of 1832 between the U.S. government and the Potawatomi people, witnessed by Everts. This treaty may concern the cession of land that the Gazette wrote about. And the Native American named “Po-ca-gan” may be Pokagan, the orator of the tribe whom Everts mentioned in the Ann Burnet court case.

In 1833 the Kentucky Gazette printed this treaty of 1832 between the U.S. government and the Potawatomi people, witnessed by Everts. This treaty may concern the cession of land that the Gazette wrote about. And the Native American named “Po-ca-gan” may be Pokagan, the orator of the tribe whom Everts mentioned in the Ann Burnet court case.

Also in 1833 Everts was appointed a district judge. But in 1836 he resigned and returned to private practice.

“My strong point was in the defense of persons charged with crime. I never prosecuted but two persons, both for murder; both were convicted and both hung.”

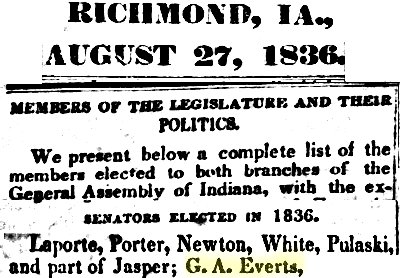

“In August 1836 I was, without my knowledge or consent, nominated for [Indiana state] senator and was elected”—on the Democratic ticket even though he was a Whig!

“In August 1836 I was, without my knowledge or consent, nominated for [Indiana state] senator and was elected”—on the Democratic ticket even though he was a Whig!

During the money crisis of 1841-1842, Everts recalled, “I was compelled to sell my farm and home.” Everts moved his family to Missouri in 1843, but “in August the sickness [probably yellow fever] commenced; death in almost every family in the country; and many were buried without much of a coffin.”

Fearing that his only child, Eliza Ann, fourteen, “would be seized with the malignant fever,” Everts moved his family to the Republic of Texas in 1844, settling in Fannin County near Bonham, which had been founded as “Fort Inglish” in 1837.

Traveling with the Evertses was Harrison Gill Hendricks, twenty-five, a lawyer who had read law under Everts in Bonham. Eliza Ann and Harrison would marry in 1847.

“There were but three or four families in the place. Fannin County embraced Collin, Denton, Cooke, and Grayson, the whole number of inhabitants were about three hundred voters.”

In the 1840s, Everts recalled, “Annexation [of the Republic of Texas by the United States] began to be agitated. I was called upon to address people that the state of Mexico would look upon its incorporation as one of the United States as a declaration of war against Mexico; and that would be virtually true, but the government of the United States would fight the battles of Texas; that General [Zachary] Taylor would prevent any invasion of Mexico into Texas and that General [Winfield] Scott in less than one year would plant the Stars and Stripes of the United States upon the walls of the city of the Montezumas and that we could dictate any terms of peace we pleased.”

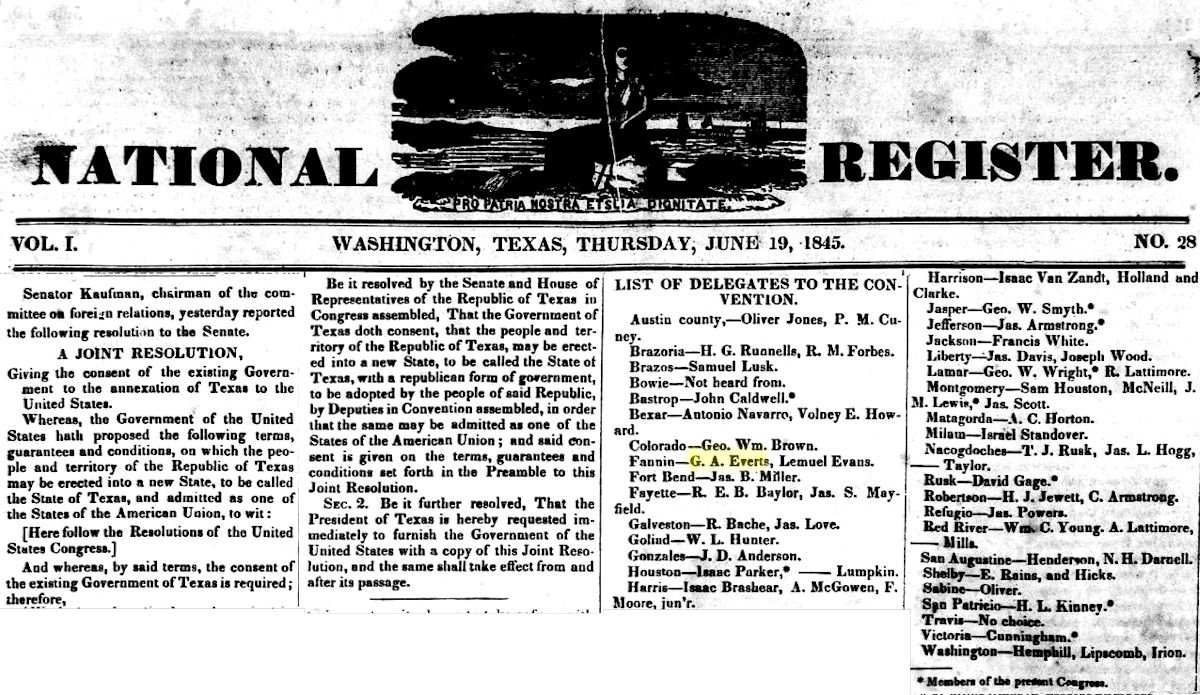

Everts was a delegate from Fannin County to the convention of 1845, which approved annexation of the Republic of Texas by the United States and wrote the new state’s first constitution. Other delegates included Sam Houston, Isaac Parker, Isaac Van Zandt, and Thomas Jefferson Rusk. Note that the National Register was published in the “other” national capital named “Washington”: Washington, Texas, capital of the republic.

Everts was a delegate from Fannin County to the convention of 1845, which approved annexation of the Republic of Texas by the United States and wrote the new state’s first constitution. Other delegates included Sam Houston, Isaac Parker, Isaac Van Zandt, and Thomas Jefferson Rusk. Note that the National Register was published in the “other” national capital named “Washington”: Washington, Texas, capital of the republic.

In January 1855 the Evertses moved to a farm in Cooke County.

“I had four good grown slaves, happy and contented. I cultivated about fifty of more acres in wheat, corn and oaks, besides a large garden of vegetables. . . . I was a good shot and hunted a great deal.”

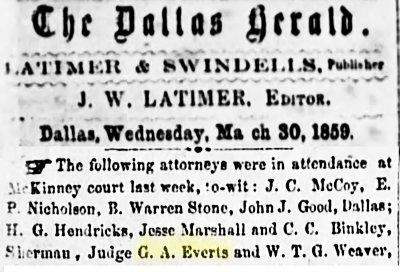

In 1859 Everts attended court in McKinney in Collin County.

In 1859 Everts attended court in McKinney in Collin County.

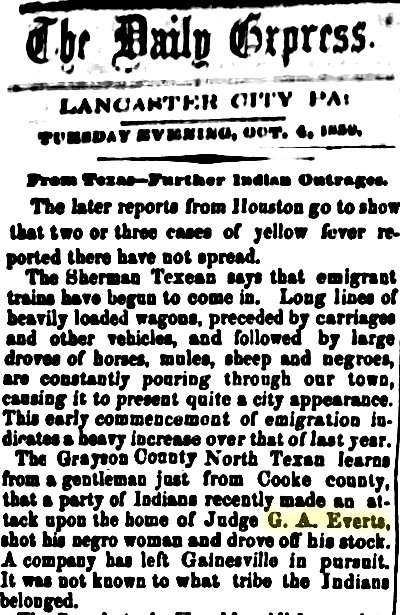

In October of that year a party of Native Americans attacked the Everts farm.

In October of that year a party of Native Americans attacked the Everts farm.

Everts recalled: “. . . the Indians made a raid on me, stole my horses and shot a Negro woman with five or seven arrows in her shoulder and back, one penetrating the right lobe of the lung, but to the astonishment of all she recovered.”

As the Civil War approached, Everts recalled, “I was opposed to secession, and in my speeches I told the people that we were sowing to the wind and would reap the whirlwind, that it [war] would be inaugurated to free the slaves, that the very first gun we fired would be the death knell of slavery, the North would finally subjugate us, and the slaves would be set free; all the North desired was the freedom of the slaves.”

The Great Hanging at Gainesville in 1862 caused Everts to fear for the safety of his family. “In 1862 I sold my farm in Cooke County, took Confederate money in pay, and before I could do anything with it the money became worthless, and I lost all.”

The Evertses fled to Navarro County, where they spent the remainder of the war.

“In 1865 my slaves went free, and all left but one. We had raised her and she had no Negro relations, so she said she would stay and nurse my wife, who at this time had become almost helpless.”

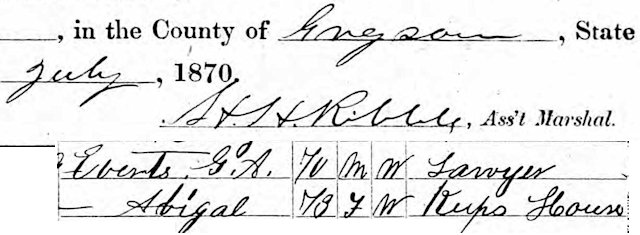

By 1870 Everts was practicing law in Grayson County.

By 1870 Everts was practicing law in Grayson County.

His wife Abigail died the next year on her birthday.

Soon after her death Everts moved to Fort Worth.

Soon after her death Everts moved to Fort Worth.

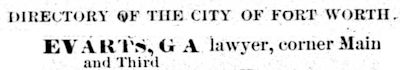

The 1877 Fort Worth city directory lists him as a lawyer.

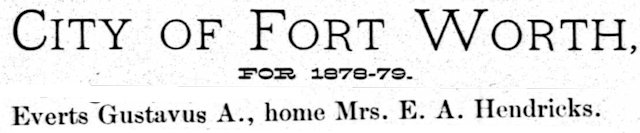

By the next year he was living with his daughter, Eliza Ann Hendricks.

By the next year he was living with his daughter, Eliza Ann Hendricks.

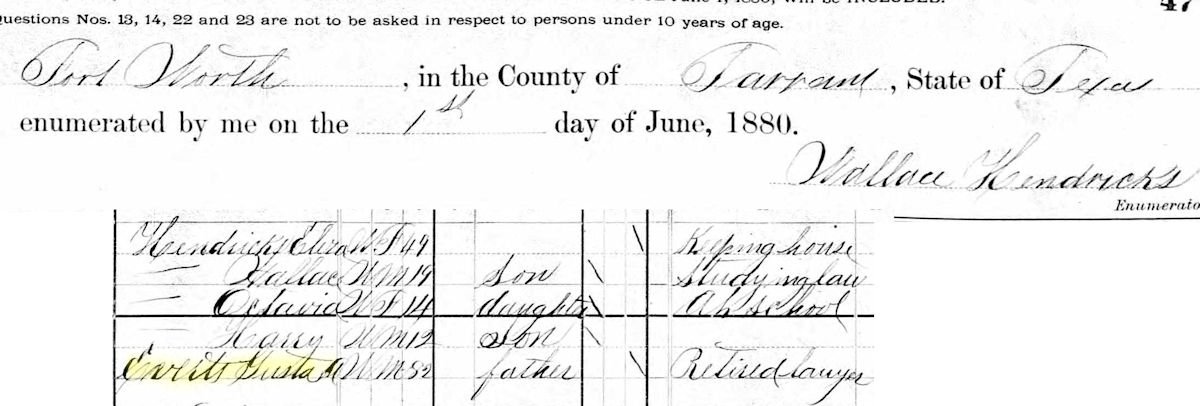

Everts was retired by the 1880 census. Note that the census enumerator was Wallace Hendricks. Now notice the second entry down. Yes, Wallace Hendricks, nineteen, son of Eliza Ann Hendricks and grandson of Gustavus Everts, enumerated his own family.

Everts was retired by the 1880 census. Note that the census enumerator was Wallace Hendricks. Now notice the second entry down. Yes, Wallace Hendricks, nineteen, son of Eliza Ann Hendricks and grandson of Gustavus Everts, enumerated his own family.

Note also that Wallace was studying law. His sister Octavia would marry George E. Bennett, who in 1891 would found Acme Brick Company.

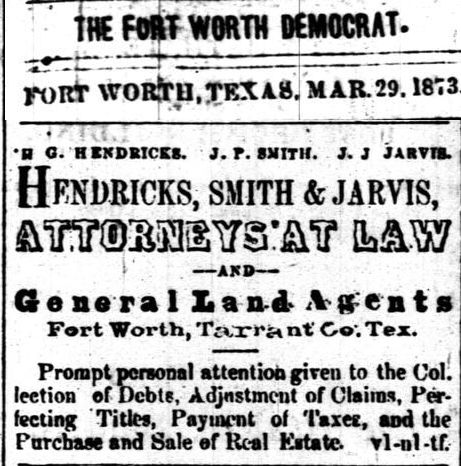

By 1880 Everts’s daughter Eliza Ann was the widow of Harrison Gill Hendricks (1819-1873), a law partner of John Peter Smith and James Jones Jarvis. Hendricks, with Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt, Ephraim Merrell Daggett, and T. J. Jennings, in 1872 had drawn up a contract promising the Texas & Pacific railroad 320 acres of land for a depot and railyard in Fort Worth in exchange for the T&P laying tracks to Fort Worth from the east.

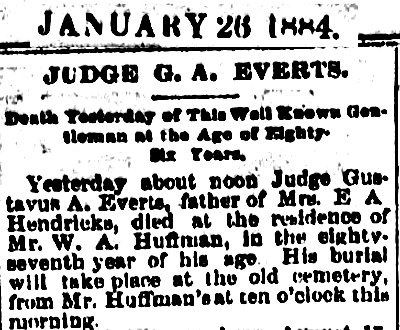

Gustavus Adolphus Everts died in 1884. Note that Everts died at the home of Walter Ament Huffman. Everts’s granddaughter Sarah (“Sallie”) was Huffman’s wife.

Gustavus Adolphus Everts died in 1884. Note that Everts died at the home of Walter Ament Huffman. Everts’s granddaughter Sarah (“Sallie”) was Huffman’s wife.

The Evertses are buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

The Evertses are buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

Gustavus and Abigail Everts died in an era when tombstones of cast zinc were popular.

His tombstone says he was born in 1790, but his autobiographical profile says he was born in 1797.