The year was 1928, and America had contracted a severe case of flying fever.

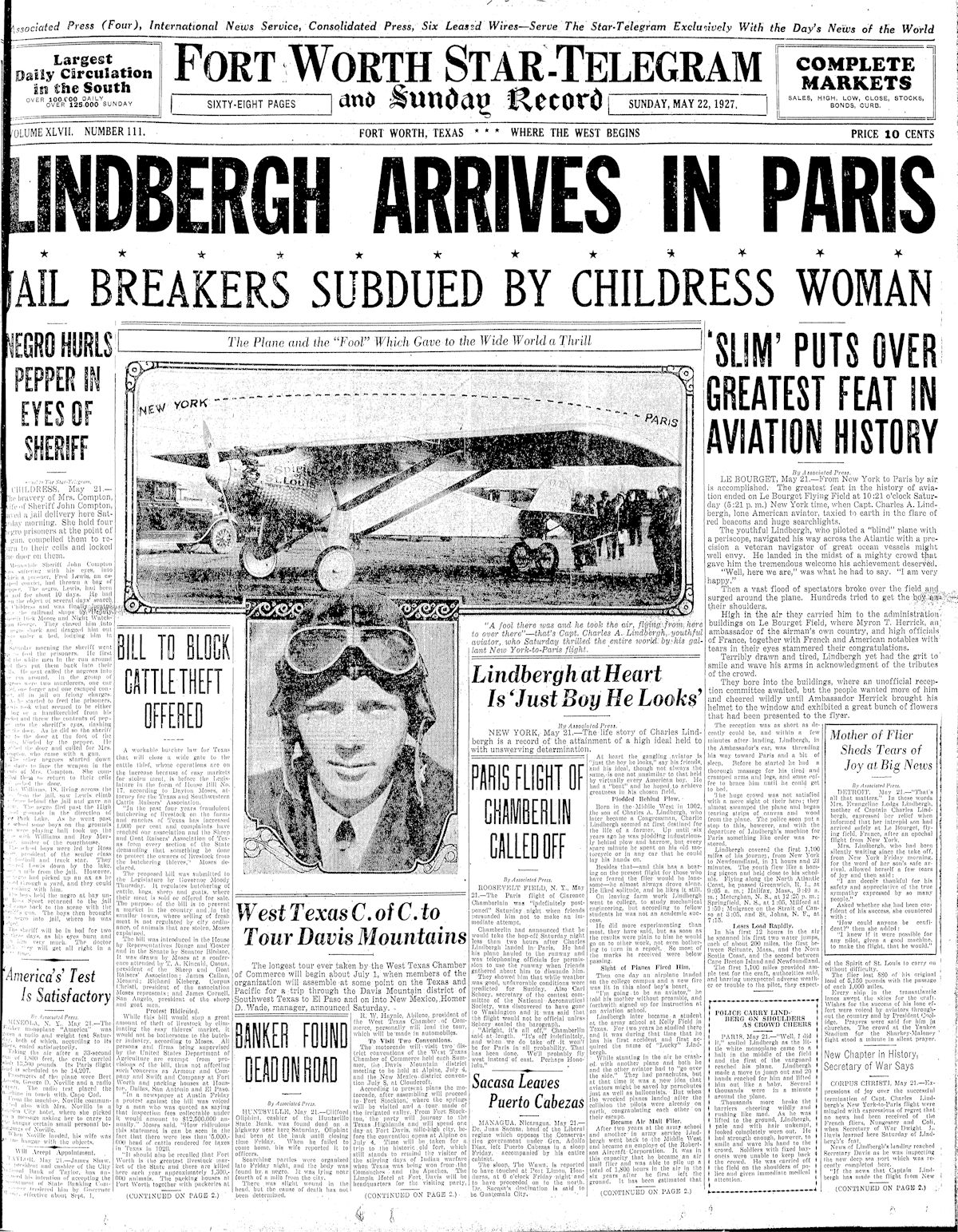

The superspreader of this contagious fever was Charles Lindbergh, whose solo trans-Atlantic flight in May 1927 had sparked the public imagination. By 1928 newspapers were filled with aviation news: Airplanes and dirigibles were being developed, tested, raced. Records for speed, altitude, distance were being set and broken. Airports were being built and airlines founded as people realized the potential of aviation for transportation, commerce, communication (airmail).

The superspreader of this contagious fever was Charles Lindbergh, whose solo trans-Atlantic flight in May 1927 had sparked the public imagination. By 1928 newspapers were filled with aviation news: Airplanes and dirigibles were being developed, tested, raced. Records for speed, altitude, distance were being set and broken. Airports were being built and airlines founded as people realized the potential of aviation for transportation, commerce, communication (airmail).

In January Al Henley and Joe Hart, two Oklahoma aviators who had been flying since World War I, announced that they would try to break the world record for endurance flying: fifty-two hours and twenty-two minutes set by two Germans in 1927.

In January Al Henley and Joe Hart, two Oklahoma aviators who had been flying since World War I, announced that they would try to break the world record for endurance flying: fifty-two hours and twenty-two minutes set by two Germans in 1927.

H&H hoped to stay in the air at least sixty hours.

And they would take off from Fort Worth’s Municipal Airport (Meacham Airport).

Financial incentive? The Fort Worth Aviation Club offered a $15,000 purse to anyone who broke the endurance record.

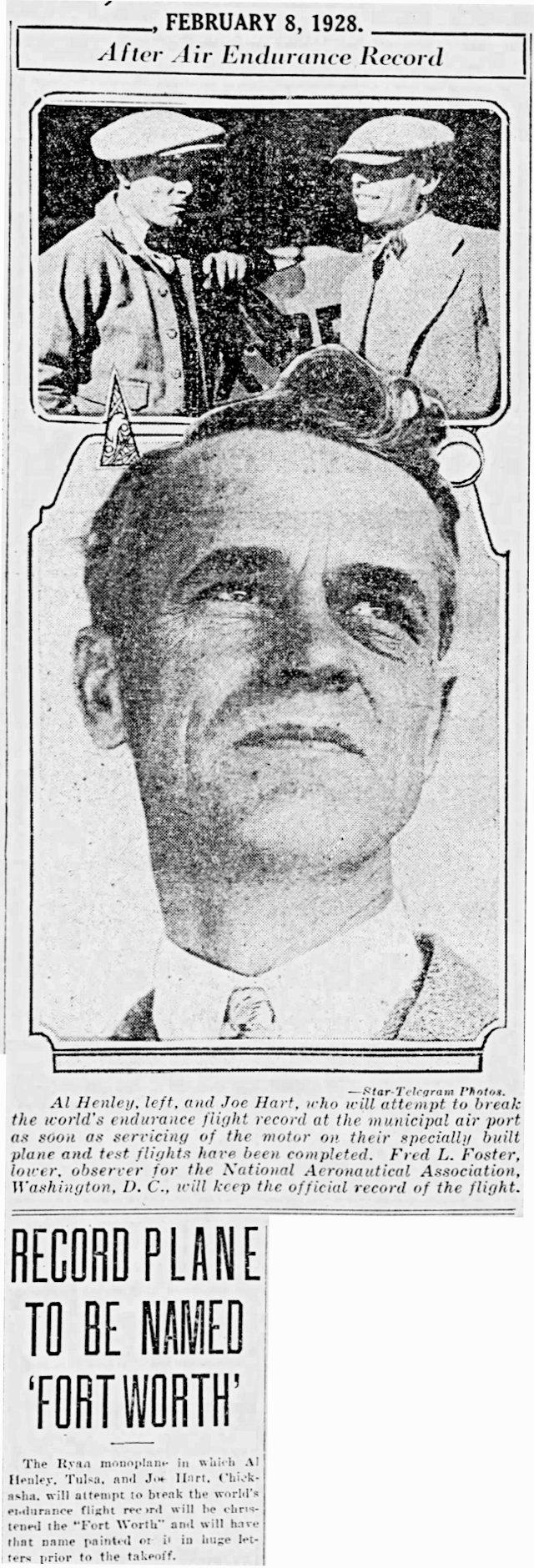

The duo would be flying an $18,000 ($270,000 today) Ryan five-seat airplane similar to Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis.

The H&H airplane had been financed by two Oklahoma oilmen.

Like Lindbergh’s plane, the Henley-Hart plane had been modified. Fuel tanks had been installed in the cabin where passengers normally sat, giving the plane a capacity of 525 gallons of fuel.

That capacity increased the airplane’s range but also increased its weight: by 2,500 pounds. The plane needed every inch of a mile of runway to get off the ground.

(Picture an albatross taking off.)

On February 8 the Star-Telegram announced that the H&H plane would be christened the “Fort Worth.”

On February 8 the Star-Telegram announced that the H&H plane would be christened the “Fort Worth.”

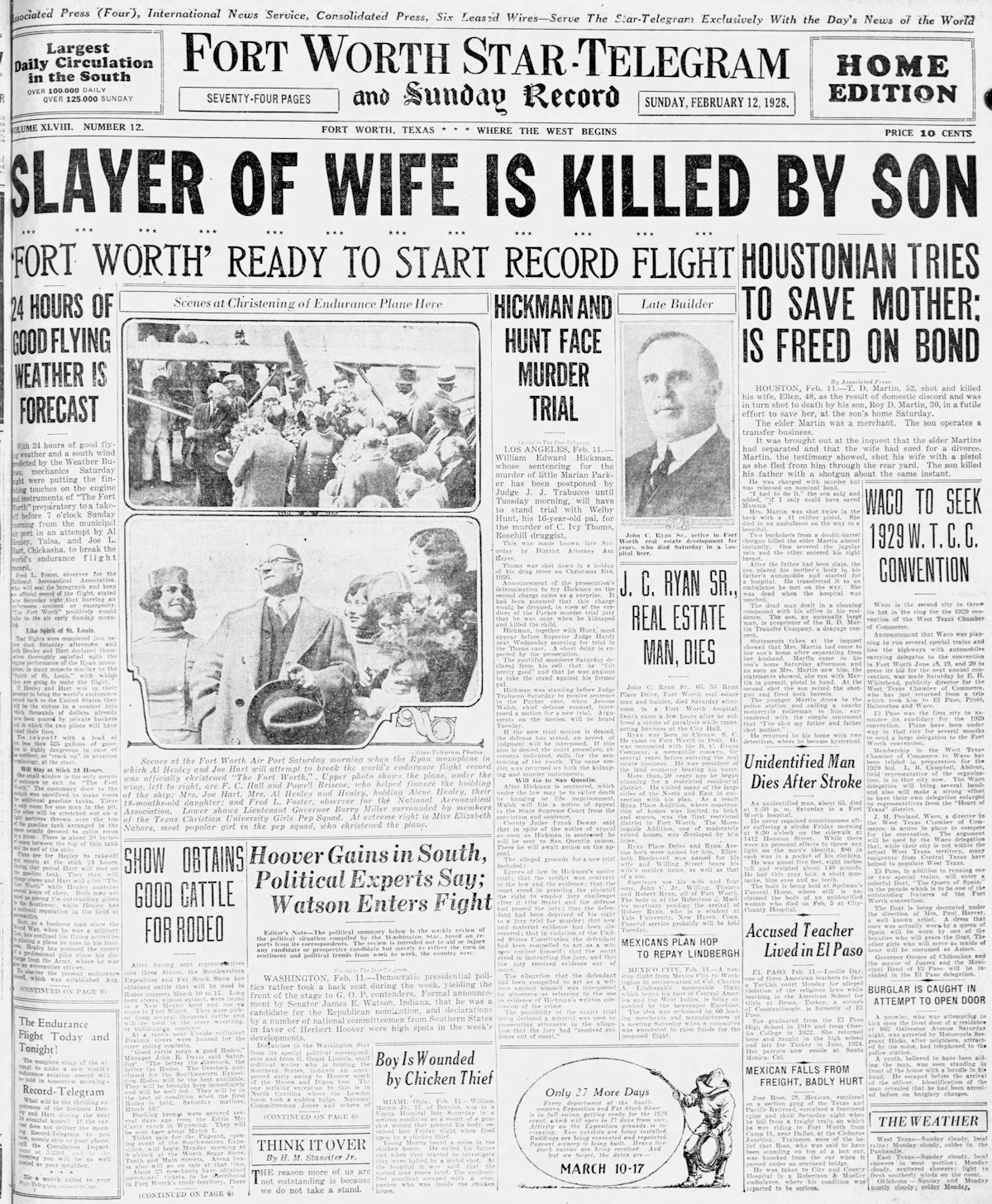

On February 11 the airplane indeed was christened. “Fort Worth” was painted on the airplane in large letters.

On February 11 the airplane indeed was christened. “Fort Worth” was painted on the airplane in large letters.

In 1928 weather dictated when airplanes could fly more than it does now. After several weather delays, on February 12 the Star-Telegram announced that Henley and Hart would take the Fort Worth up later that day. Good weather was forecast for twenty-four hours.

A representative of the National Aeronautical Association placed a barograph in the airplane to verify that the Fort Worth had not landed before its flight ended. The representative also would time the record attempt.

Another official observer of the flight would be Amon Carter.

Henley planned to get the Fort Worth off the ground and take the first shift, flying for twenty-four hours. He would circle the airport while Hart slept on top of one of the added gas tanks in the cabin. After twenty-four hours of burning fuel the airplane would be light enough to fly safely farther afield, but the entire flight would be confined to the Fort Worth area.

But on February 12 the two aviators encountered the first of several disappointments. That forecast of good weather proved false as rain fell, rendering the runway too soft for such a heavy airplane to take off.

But on February 12 the two aviators encountered the first of several disappointments. That forecast of good weather proved false as rain fell, rendering the runway too soft for such a heavy airplane to take off.

Weather continued to prevent a takeoff until February 19.

Weather continued to prevent a takeoff until February 19.

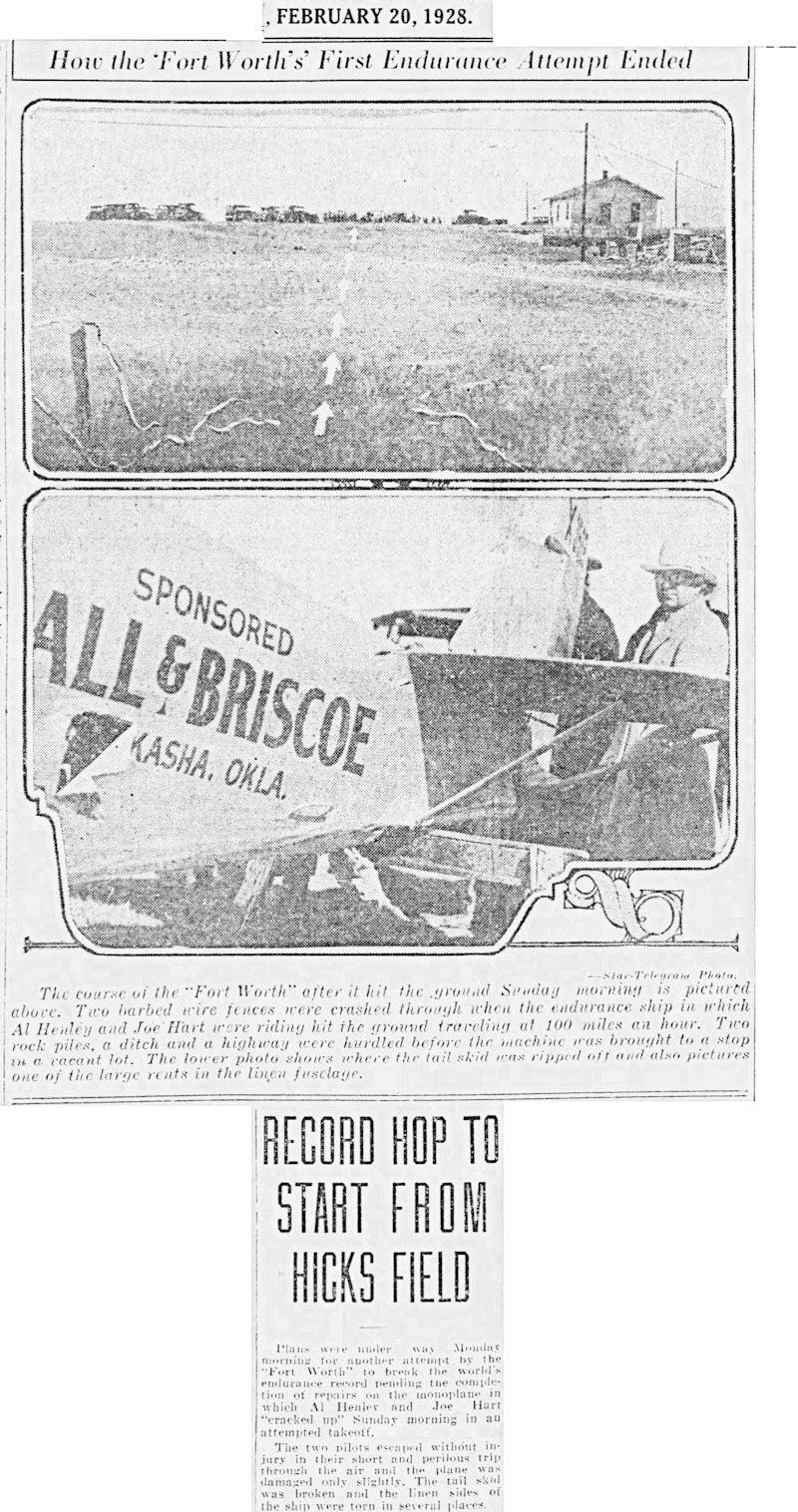

A crowd of two thousand gathered at the airport that morning, cheering as the Fort Worth taxied down the runway and lifted off. But as the fuel-laden plane flew low over the runway struggling to gain altitude it passed over dips that rendered it unable to climb. As the airplane left the end of the runway it was only twenty feet off the ground and headed for a neighborhood southwest of the airport.

The plane was barely clearing housetops as Henley brought it down to the ground. The plane taxied for about one thousand feet, tearing through two barbed wire fences and through one back yard before coming to a stop in a vacant lot on Lorraine Avenue a mile from the airport.

The plane’s tail skid was damaged, and the linen covering of the fuselage was ripped, but no one had been injured. People who witnessed the impromptu ground-level tour of the North Side praised Henley for his handling of the airplane.

H&H decided to move their next attempt to the old Hicks Field at Saginaw because the terrain was deemed more suitable for the heavy airplane.

After more weather delays, a week later, on February 26, Henley and Hart tried again.

After more weather delays, a week later, on February 26, Henley and Hart tried again.

Several thousand people had gathered early at the old Hicks Field. While they waited, filling the airplane’s tanks took three hours because the fuel was filtered through chamois skin.

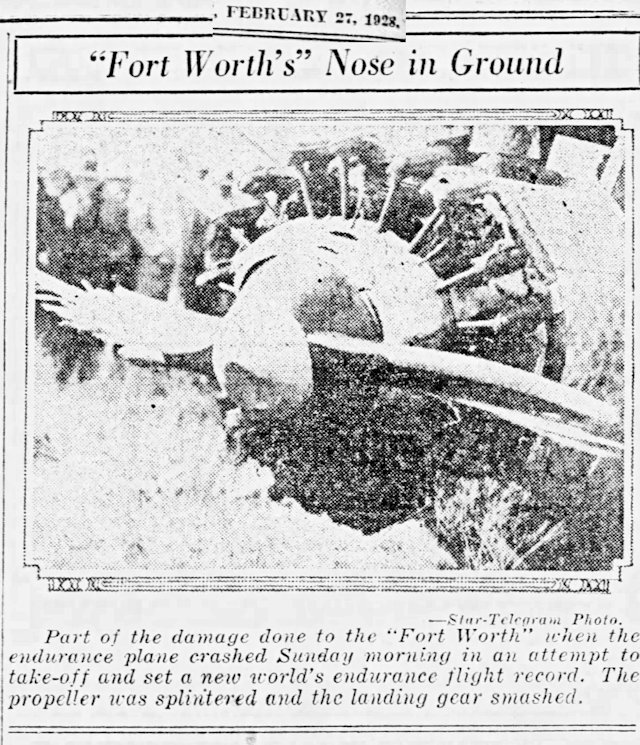

As the Fort Worth taxied down the runway—just a pasture—the left wheel collapsed under the weight, and the airplane nosed over. The propeller was damaged, the linen covering again was ripped, the landing gear was torn away.

Fuel spilled from ruptured tanks in the cabin, and sightseers smoking cigarettes crowded around the airplane until police established a “danger zone.”

Again no one was injured.

Joe Hart went back to Oklahoma to attempt a solo attempt at the endurance record.

Joe Hart went back to Oklahoma to attempt a solo attempt at the endurance record.

In May Hart, flying alone, took off from Chickasha in a plane similar to the Fort Worth. But a rain storm and an oil leak forced him down after three hours and forty minutes.

A few days later Hart tried again. But after nine hours and thirty-eight minutes he was shut down by motor trouble.

A few days later Hart tried again. But after nine hours and thirty-eight minutes he was shut down by motor trouble.

He was a long way from the record of fifty-two hours.

Meanwhile Al Henley took part in the Ford-sponsored national air tour. He was the first of twenty-four fliers to reach Fort Worth from Tulsa.

Meanwhile Al Henley took part in the Ford-sponsored national air tour. He was the first of twenty-four fliers to reach Fort Worth from Tulsa.

In January 1929 Al Henley was attempting to land at San Angelo’s new municipal airport when his plane crashed, killing him and two other men on board.

In January 1929 Al Henley was attempting to land at San Angelo’s new municipal airport when his plane crashed, killing him and two other men on board.

With that crash also died all hope that Henley and Hart would set a world endurance record.

But other fliers would continue to make assaults on the record, and by the time fliers again tried to break the endurance record flying from Fort Worth, fifty-two hours in the air and a dime would buy you a cup of aviation fuel.