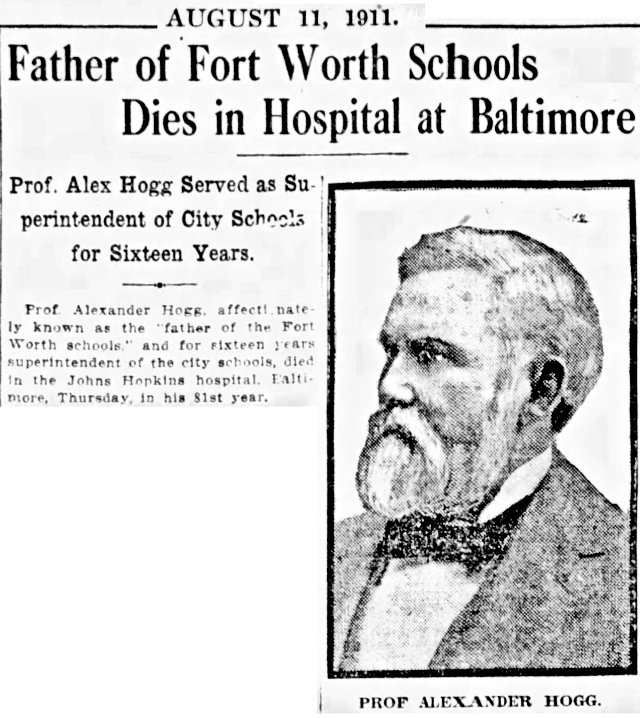

He was “the father of Fort Worth schools,” their first superintendent, elected when the public school system was organized in 1882.

But first Alexander Hogg spent thirty years in the classroom. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

Hogg was born in Virginia in 1830.

Robert Lee Paschal (himself a giant in Fort Worth education) wrote of Hogg in 1939: “Like many another farm boy he plowed in the summer but attended the local academy in the winter. Then one day he let go the handles of the plow, determined to get whatever education was available. He had no money to pay his way through college. . . . He had picked up enough mathematics to earn some money by surveying, but he made the greater part of the necessary money by teaching. There was no schoolhouse, but he was not to be thwarted by a small difficulty like that. He built him a log schoolhouse with his own hands.”

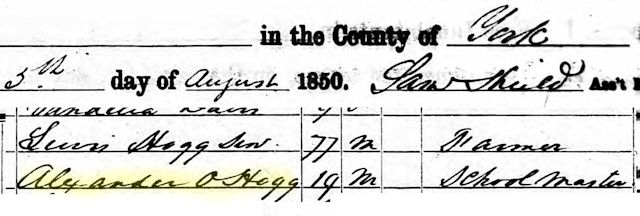

The 1850 census lists Hogg, then nineteen, as a “school master.”

The 1850 census lists Hogg, then nineteen, as a “school master.”

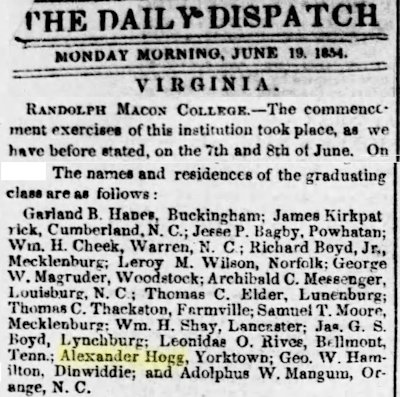

But Hogg continued his own education. Paschal wrote that Hogg enrolled in Randolph-Macon College in Virginia and “by tutoring the more wealthy students was able to pay all expenses.” He graduated in 1854.

But Hogg continued his own education. Paschal wrote that Hogg enrolled in Randolph-Macon College in Virginia and “by tutoring the more wealthy students was able to pay all expenses.” He graduated in 1854.

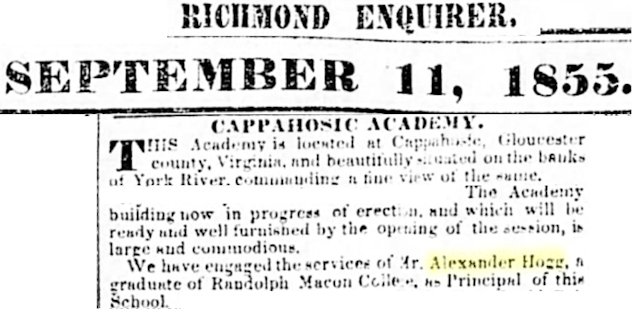

Paschal wrote: “Immediately after his graduation there appeared in the Richmond Inquirer the following advertisement: ‘Wanted by one who selects through choice and expects to follow as a profession a place to teach school.’ He [Hogg] found the place in Gloucester County, where he opened a school for boys.”

Paschal wrote: “Immediately after his graduation there appeared in the Richmond Inquirer the following advertisement: ‘Wanted by one who selects through choice and expects to follow as a profession a place to teach school.’ He [Hogg] found the place in Gloucester County, where he opened a school for boys.”

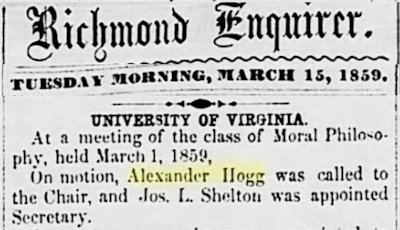

In 1859 Hogg married Eliza Buckner Cooke. Paschal wrote: “Immediately after his marriage he entered the University of Virginia, where a few weeks later the faculty selected him, a graduate student, as teacher of Latin.

In 1859 Hogg married Eliza Buckner Cooke. Paschal wrote: “Immediately after his marriage he entered the University of Virginia, where a few weeks later the faculty selected him, a graduate student, as teacher of Latin.

“After a year or two in Virginia, he moved to North Carolina, where he taught Latin and Greek in a boys’ school until the school closed in 1862 on account of the war.

“He volunteered for the Confederate Army and served in a hospital and later in the cavalry.

“After the war he taught mathematics in Washington College, Maryland. Two years later he secured a professorship in East Alabama College at Auburn. After a few years here he became superintendent of the public schools in Montgomery.”

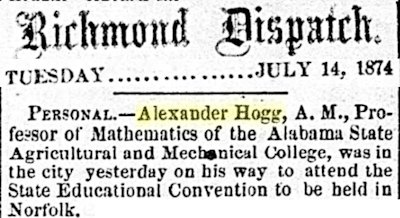

By 1874 Hogg was a professor at Alabama A&M.

By 1874 Hogg was a professor at Alabama A&M.

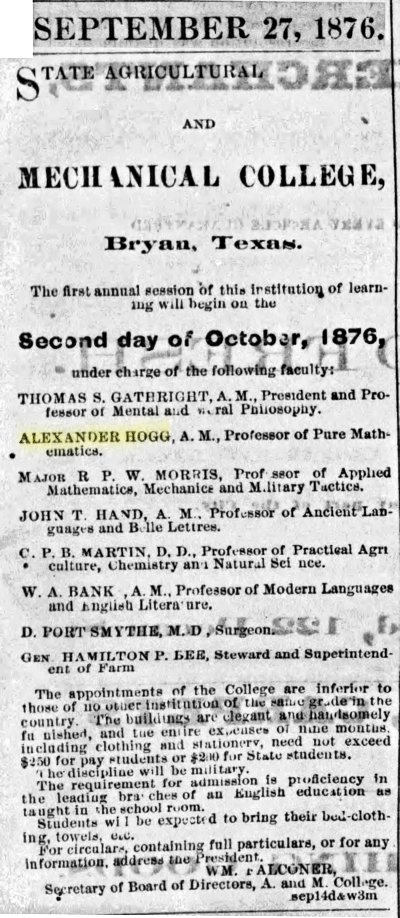

But soon another A&M called. Paschal wrote: “In 1876 the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas opened its doors, and he came to Texas at the request of Governor [Richard] Coke to take the chair of mathematics in that institution. Here he spent four years.”

But soon another A&M called. Paschal wrote: “In 1876 the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas opened its doors, and he came to Texas at the request of Governor [Richard] Coke to take the chair of mathematics in that institution. Here he spent four years.”

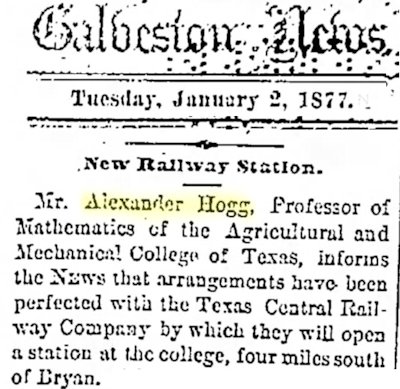

Hogg helped College Station get its station.

Hogg helped College Station get its station.

About 1879 Hogg left education briefly to work for the railroads, first for the Houston & Texas Central railroad as a civil engineer. About 1880 he went to Marshall to work in the land office of the Texas & Pacific railroad.

About 1879 Hogg left education briefly to work for the railroads, first for the Houston & Texas Central railroad as a civil engineer. About 1880 he went to Marshall to work in the land office of the Texas & Pacific railroad.

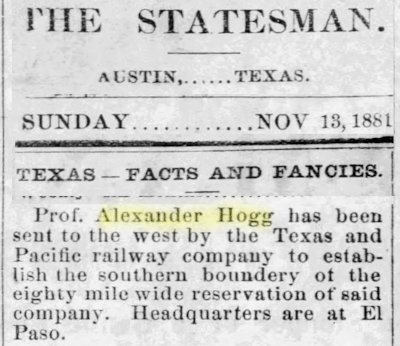

As Texas & Pacific extended its track west from Fort Worth to El Paso, Hogg was sent to survey the southern boundary of the railroad’s right-of-way.

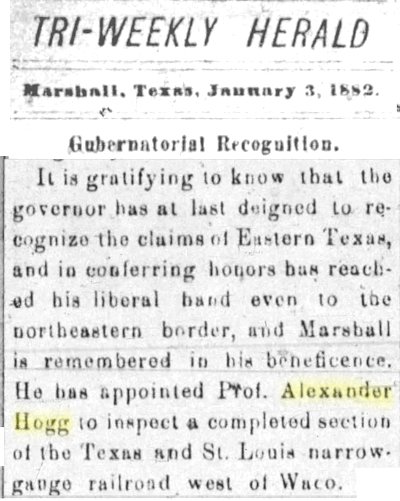

Governor Oran Roberts appointed Hogg to inspect a section of the Texas and St. Louis railroad west of Waco.

Governor Oran Roberts appointed Hogg to inspect a section of the Texas and St. Louis railroad west of Waco.

Hogg was living in Marshall, headquarters of T&P in Texas, and wearing both hats—educator and railroad man—in 1882 when Fort Worth Mayor John Peter Smith invited him to put on his educator hat and come to Fort Worth to deliver an address at a public meeting.

By 1882 Fort Worth’s civic leaders had been fighting the courts—and some Fort Worth residents—since 1877 in an effort to organize a tax-funded public school system.

Paschal wrote: “He [Hogg] came . . . to make a speech in favor of local taxation for public schools. This was in the spring of 1882.”

Judge James C. Scott in 1911 recalled: “Professor Hogg carried the meeting with his eloquence, showing the progress in the management of the schools on a more thorough, universal education of the people. His strong principle was that education made more useful citizens and lessened crime.”

Hogg’s speech was a factor in voters finally approving a public school system later in 1882. Hogg’s speech also was a factor in determining who would be the system’s first permanent superintendent.

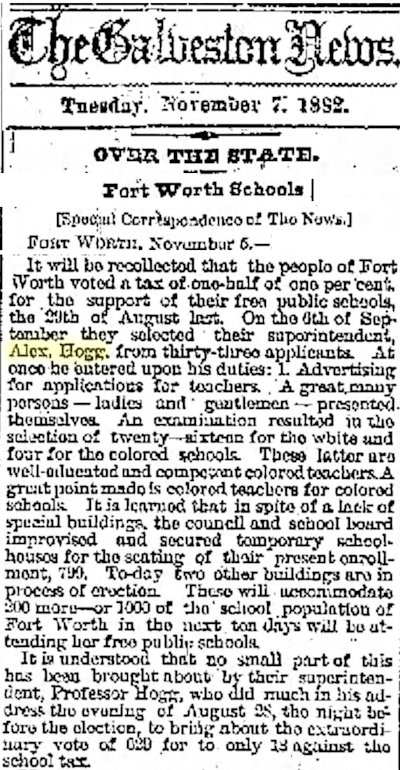

After the school system was approved, the city council elected a school board. That board’s first action was, Paschal wrote, “to place an advertisement for a superintendent in the local paper and in two St. Louis papers. At the second meeting of this board, Sept. 5, 1882, there were thirty-three applicants; Alexander Hogg was elected.”

Paschal wrote: “Professor Hogg said that when he became superintendent of our schools in 1882, that the schools did not own a ‘shingle or an ink well.’

“He and the board and the city council had to get busy. Private school buildings and churches were rented; some of these were in bad condition and had to be repaired; suitable sites were chosen for school houses to be erected; courses of study had to be outlined; rules and regulations for the conduct of the schools formulated; teachers selected; organization had to be effected. Five school houses for the white schools were rented, and a church for the use of the colored schools; sixteen white teachers were selected . . . Four negro teachers were chosen, among them I. M. Terrell, in whose honor the high school for his race is named. The schools opened their doors on October 16, 1882.

“For all this work he [Hogg] received $1,500 [$40,000 today] a year, the principals, $60 [$1,600 today] per school month, and teachers $40 or $50. To pay these salaries, to rent and construct buildings, to buy needed equipment, Mayor J. P. Smith announced at the first meeting of the board that there was available the sum of $10,000 [$268,000 today], plus such an amount as might be raised by the local school tax.”

For political reasons, in 1889 the school board replaced Hogg, and he became the first superintendent of Waxahachie’s public schools. At that time he also was president of the State Teachers Association.

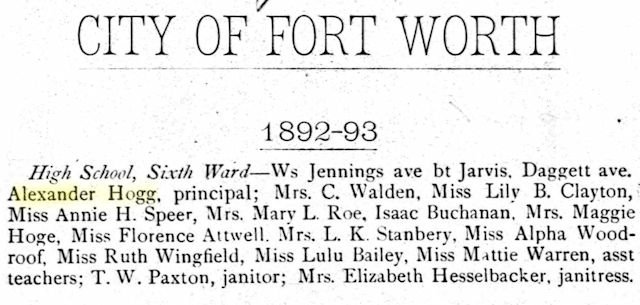

But by 1891 Hogg was back in Fort Worth, serving as the first principal of the new Fort Worth High School. Hogg used that position as a steppingstone to his second term as superintendent in 1892, serving another four years. Note that Lily B. Clayton was a teacher at Fort Worth High School in 1892. (R. L. Paschal would become principal of the school in 1906.)

But by 1891 Hogg was back in Fort Worth, serving as the first principal of the new Fort Worth High School. Hogg used that position as a steppingstone to his second term as superintendent in 1892, serving another four years. Note that Lily B. Clayton was a teacher at Fort Worth High School in 1892. (R. L. Paschal would become principal of the school in 1906.)

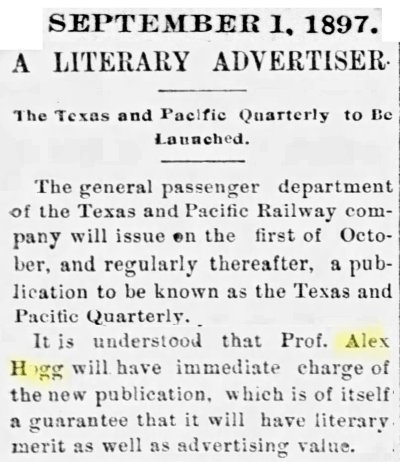

Then Hogg hit the rails again: From 1896 to 1902 he was back with the Texas & Pacific railroad. He founded, Paschal wrote, “the first literary periodical published by any railway company, namely, The Texas and Pacific Quarterly.”

Then Hogg hit the rails again: From 1896 to 1902 he was back with the Texas & Pacific railroad. He founded, Paschal wrote, “the first literary periodical published by any railway company, namely, The Texas and Pacific Quarterly.”

In 1900 Hogg’s wife died. Paschal wrote: “The love of [Latin] stayed with him to the end. The Star-Telegram quoted Hogg as saying on the death of his wife . . .: ‘Non obiit, abitt,’ she has not died, she has gone away.”

In 1902, at age seventy-two, Hogg was elected superintendent of Fort Worth schools for the third time. During his final term he introduced manual training, home economics, and nature study to the curriculum.

Professor Hogg was a strong advocate of education for women and vocational training.

A zealous crusader for “equal education of the head, heart, and hand,” he was a popular speaker around the state and beyond. He also wrote prolifically on education. His book The Railroad in Education: or What Steam and Steel, Science and Skill Have Done for the World listed what he considered to be the three great factors of modern civilization: the printing press, public schools, and the railroads. He wrote: “The newspaper furnishes the matter, the public school prepares the reader, and the railroad carries the printed page to every hamlet, town, and city.”

In 1906 Alexander Hogg retired.

When Fort Worth had established its ward schools, the schools were named according to their ward number. For example, “First Ward School,” “Second Ward School.” Later the school board began to name schools after figures in Texas history (Houston, Austin, De Zavala). In 1909 the school board made another change, announcing that new schools would be named after “pioneers and public-spirited citizens of Fort Worth” (Richard L. Vickery, Sam Rosen, Walter Huffman).

When Fort Worth had established its ward schools, the schools were named according to their ward number. For example, “First Ward School,” “Second Ward School.” Later the school board began to name schools after figures in Texas history (Houston, Austin, De Zavala). In 1909 the school board made another change, announcing that new schools would be named after “pioneers and public-spirited citizens of Fort Worth” (Richard L. Vickery, Sam Rosen, Walter Huffman).

By 1909 the wards schools were called “district schools.” The new school on West Terrell Avenue, built on the former homestead of B. B. Paddock, carried two names: “Eleventh District School” and “Alexander Hogg School.”

By 1909 the wards schools were called “district schools.” The new school on West Terrell Avenue, built on the former homestead of B. B. Paddock, carried two names: “Eleventh District School” and “Alexander Hogg School.”

In 1910 professor Hogg became ill. He went to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for surgery. Gravely ill in 1911, he telegraphed a message to the graduating class of Central High School: “Remember you owe to city, state, and republic a broader patriotism and better citizenship. You have one country, one constitution, and one flag. Never cease your efforts until ‘Old Glory’ floats from every school building in the city.”

Alexander O. Hogg died August 10, 1911 in Baltimore. He was eighty-one years old.

Alexander O. Hogg died August 10, 1911 in Baltimore. He was eighty-one years old.

Fort Worth’s public schools—about twenty-four at the time—were draped in black by Superintendent J. W. Cantwell and school board member George C. Clarke.

Fort Worth’s public schools—about twenty-four at the time—were draped in black by Superintendent J. W. Cantwell and school board member George C. Clarke.

Hogg’s funeral was held at his home. Texas & Pacific railroad dispatched a private car of mourners.

Hogg’s funeral was held at his home. Texas & Pacific railroad dispatched a private car of mourners.

Pallbearers included John Wesley Everman, for whom the town is named and who had worked for I&GN railroad and later for Texas & Pacific, W. H. Abrams of T&P, professor Ernest Parker, and Dr. Khleber (as in Khleber Miller Van Zandt) Heberden Beall.

The Fort Worth Record wrote of Hogg’s funeral: “And to further attest the popularity of the man with all classes of people, several of the leading negroes of the city paid their respects by standing on the lawn of the residence throughout the funeral exercises.”

Reverend Hiram Abiff Boaz delivered the funeral oration, saying of Hogg: “It is generally conceded that he organized the schools of the city, and he is affectionately referred to as the father of the city schools. . . . Many men in Texas have achieved distinction, but the names of but few of our educators have gone beyond the confines of our state. But we are gathered today around the remains of the most distinguished educator that has labored in this commonwealth. He was known not only in Texas but by every school man of prominence in the nation, for his name had gone throughout the United States.”

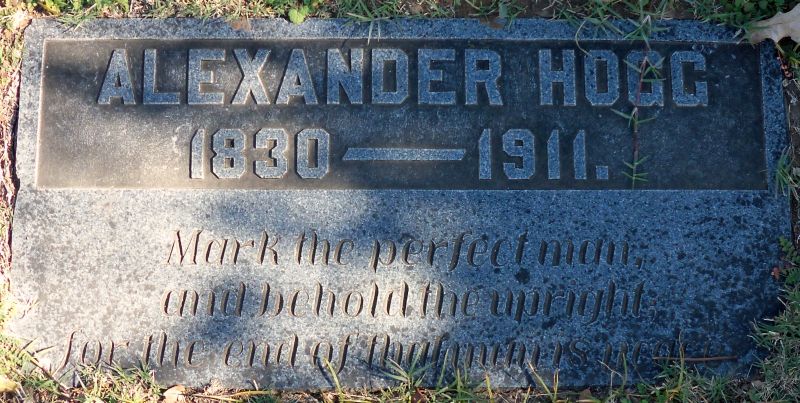

Professor Alexander O. Hogg is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

Professor Alexander O. Hogg is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

“Mark the perfect man,

and behold the upright;

for the end of that man is peace” (Psalms 37:37)

I attended Alexander Hogg

Elementary School for a short time in 1958/59.

I was staying with my grandmother while my parents were being transferred here.

My Grandmother lived on Hemphill St. So it was a short walk.

I remember the old staircase in the school.

Classes were upstairs and the cafeteria was in the basement.

I sure miss those times.

Re: your reply about Sam Rosen, I did a lot of research on him for my book, including interviews with Sam Rosen II, his grandson. My grandmother consulted with Sam Rosen about caring for a couple of Jewish orphans at the abandoned convent. She asked him about what to feed them and about where to send them to school, etc. There are quite a few articles about him in the Star-Telegram and in some Jewish publilcations.

Have you done a story on Sam Rosen?

Jim, like your grandmother’s, his is a heck of an immigrant success story.