Like most boys, he dreamed of having a model train set.

And like many of those boys, he got his model train set.

The difference is that his train set was a full-scale model.

And by the time he was sixty-two he would have a different locomotive for every day of the year.

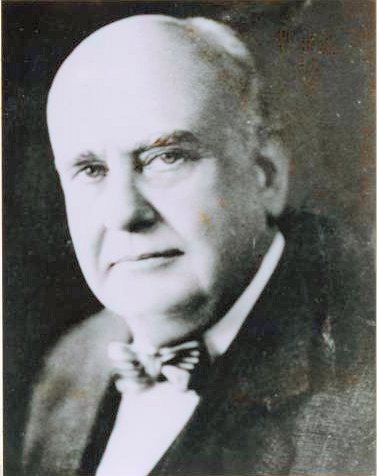

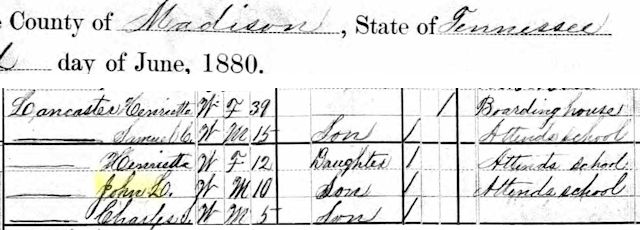

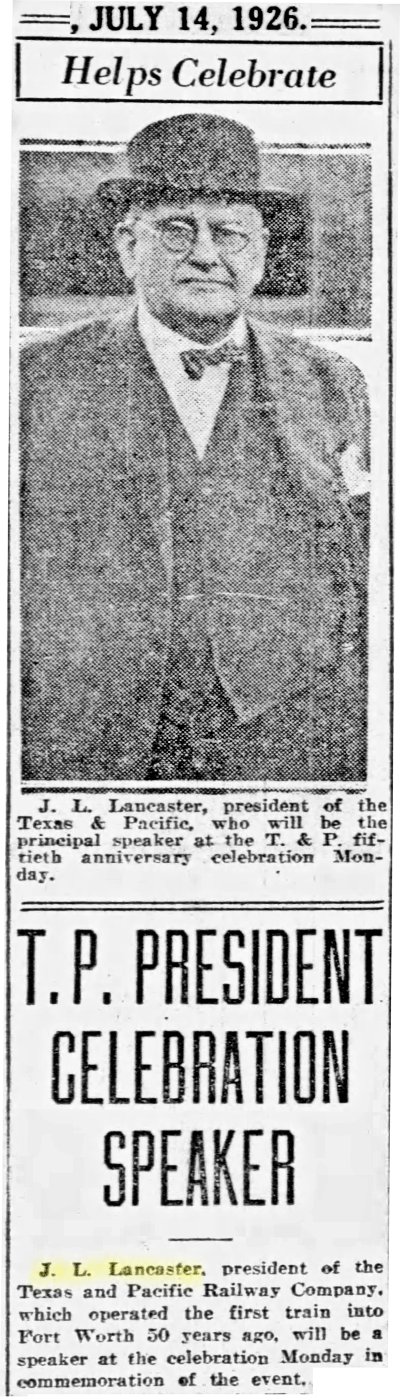

John Lynch Lancaster was born in 1869 in Tennessee. (Photo from Grace Museum.)

John Lynch Lancaster was born in 1869 in Tennessee. (Photo from Grace Museum.)

He got a grade school education and by age sixteen was workin’ on the railroad. He began at the bottom, working in the civil engineering department of the Illinois Central railroad as a rodman, holding the rods for a survey crew.

He got a grade school education and by age sixteen was workin’ on the railroad. He began at the bottom, working in the civil engineering department of the Illinois Central railroad as a rodman, holding the rods for a survey crew.

Early on he lived the gypsy life of a railroad man, working for the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe; Tennessee Midland; Seaboard Air Line; Chesapeake & Ohio; Ohio & Southern; Cleveland, Akron & Columbus; Mobile & Ohio, and Missouri Pacific railroads.

In 1906 he was thirty-seven and knew the railroad business from the ballast up. He was elected vice president of the Union Railway Company of Memphis. He became president in 1907. He held that position until 1915, when he moved to Texas to join the Texas & Pacific railroad as assistant to the vice president.

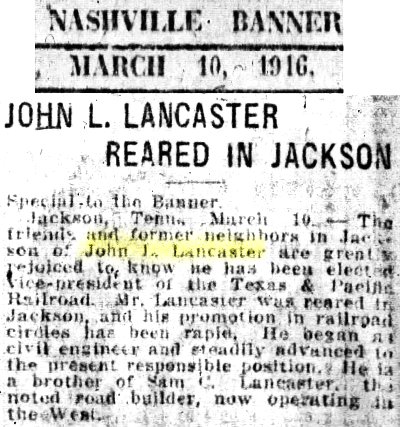

In 1916 he was promoted to vice president.

In 1916 he was promoted to vice president.

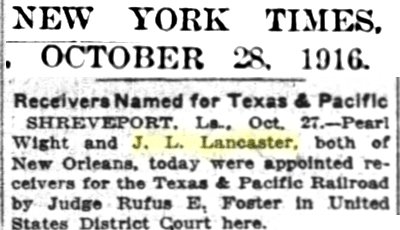

But by then the T&P was in trouble. By the close of 1915 the company had been $3 million ($77 million today) in debt. In October 1916 Lancaster, as vice president, and New Orleans banker Pearl Wight were appointed receivers.

But by then the T&P was in trouble. By the close of 1915 the company had been $3 million ($77 million today) in debt. In October 1916 Lancaster, as vice president, and New Orleans banker Pearl Wight were appointed receivers.

As Lancaster began trying to reorganize the company, in 1917 he became Texas & Pacific’s fifth president, succeeding George J. Gould, son of railroad tycoon Jay Gould. (On February 1, 1899 George J. Gould, then president of the T&P in Texas, had pressed a button in New York City, symbolically beginning construction of Fort Worth’s new passenger depot.)

As Lancaster began trying to reorganize the company, in 1917 he became Texas & Pacific’s fifth president, succeeding George J. Gould, son of railroad tycoon Jay Gould. (On February 1, 1899 George J. Gould, then president of the T&P in Texas, had pressed a button in New York City, symbolically beginning construction of Fort Worth’s new passenger depot.)

Just as Lancaster began to turn the company around, America went to war. During World War I Lancaster was manager for the federal railway administration of the Texas & Pacific and a number of other railroads, including the Cotton Belt and the International & Great Northern.

After the war Lancaster continued to resurrect the Texas & Pacific like an iron Lazarus. According to From Ox-Teams to Eagles: A History of the Texas & Pacific Railway, T&P’s tracks were renovated with heavier ballast and heavier rails. And T&P would need heavier rails as it began using the behemoth (ninety-seven feet long, 2-10-4 configuration) Texas class of locomotive (T&P engine no. 610 on static display at the Texas State Railroad is a 2-10-4).

The first of the Texas-class locomotives went into service in 1925.

Also under Lancaster the company spent millions of dollars to enlarge existing—or to build new—passenger and freight terminals in New Orleans, Shreveport, and Alexandria, Louisiana, Dallas, and other cities.

But Fort Worth was Lancaster’s showcase. Between 1928 and 1931—during the Great Depression—T&P would spend $13 million ($199 million today) here.

Lancaster spoke in Fort Worth on the fiftieth anniversary of the arrival of the first T&P train in 1876.

Lancaster spoke in Fort Worth on the fiftieth anniversary of the arrival of the first T&P train in 1876.

Lancaster used the occasion to announce that Texas & Pacific would build a new railyard on 1,600 acres on the western outskirts of town. He predicted that the new yard would add five thousand to Fort Worth’s population.

Lancaster used the occasion to announce that Texas & Pacific would build a new railyard on 1,600 acres on the western outskirts of town. He predicted that the new yard would add five thousand to Fort Worth’s population.

The new railyard would cost $5 million ($73 million today).

The new yard had sixty miles of tracks and could handle five thousand cars daily. The yard had the Southwest’s first “hump” to switch cars by gravity feed into the classification yard. The speed and direction of a car into the classification yard were controlled by electrically operated car retarders and switch machines that were operated by men stationed in towers. Track scales weighed and recorded the weight of a car while it was rolling. The yard had a crane capable of lifting a Texas-class locomotive, which weighed 225 tons. The yard opened with a work force of almost seven hundred.

The new yard had sixty miles of tracks and could handle five thousand cars daily. The yard had the Southwest’s first “hump” to switch cars by gravity feed into the classification yard. The speed and direction of a car into the classification yard were controlled by electrically operated car retarders and switch machines that were operated by men stationed in towers. Track scales weighed and recorded the weight of a car while it was rolling. The yard had a crane capable of lifting a Texas-class locomotive, which weighed 225 tons. The yard opened with a work force of almost seven hundred.

Fort Worth honored Lancaster in 1928 as the new railyard opened.

Fort Worth honored Lancaster in 1928 as the new railyard opened.

And by the way, the T&P wasn’t John L. Lancaster’s only full-scale train set. The Star-Telegram wrote in 1928 that Lancaster also was president of these railroads:

Weatherford, Mineral Wells & Northwestern

Denison & Pacific Suburban

Cisco & Northeastern Railway

Abilene & Southern

Pecos Valley Southern

He was only vice president of the Texas & Pacific-Missouri Pacific Terminal Railroad of New Orleans and a mere director of the International & Great Northern railroad.

In 1929 Lancaster revealed plans for a new passenger depot and new freight depot for Fort Worth on the south end of downtown. Both buildings would be designed by the architectural firm of Wyatt Hedrick.

In 1929 Lancaster revealed plans for a new passenger depot and new freight depot for Fort Worth on the south end of downtown. Both buildings would be designed by the architectural firm of Wyatt Hedrick.

But the two building projects were contingent on Fort Worth voters approving a $3 million bond package.

They did.

They did.

The freight terminal opened in June 1931.

The freight terminal opened in June 1931.

The passenger terminal opened in November 1931.

The passenger terminal opened in November 1931.

In addition to the two terminals, the city and T&P built three new underpasses on each end and in between the two terminals at Main, Jennings, and Henderson streets.

In full-page ads Fort Worth congratulated John L. Lancaster, T&P railroad, and itself.

In full-page ads Fort Worth congratulated John L. Lancaster, T&P railroad, and itself.

In November 1931 Fort Worth presented a silver loving cup to John Lancaster, whose railyard and two terminals translated into jobs and taxes at the end of the Depression.

In November 1931 Fort Worth presented a silver loving cup to John Lancaster, whose railyard and two terminals translated into jobs and taxes at the end of the Depression.

“Fort Worth has done as much for Texas & Pacific,” Lancaster said, “as we have done for Fort Worth.”

By 1931 Lancaster’s Texas & Pacific railroad was on a roll. The company owned 365 locomotives, 236 passenger cars, and 9,816 freight cars. Lancaster’s company earned $24 million ($409 million today) in freight revenue, $3.2 million ($54 million today) in passenger revenue, and $2.7 million ($46 million today) in other revenue.

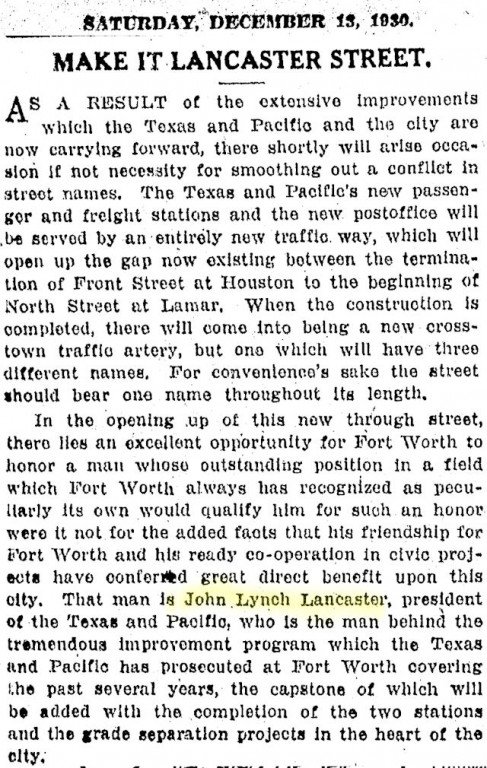

In 1930 the street that passes in front of the two new T&P terminals had three names. On the east side of town it was the “Dallas-Fort Worth Pike.” Through downtown it was “Front Street” on the east and “North Street” on the west. Late in 1930 the Star-Telegram in an editorial suggested that the street be given just one name: “Lancaster” in honor of the man who was transforming the street.

In 1930 the street that passes in front of the two new T&P terminals had three names. On the east side of town it was the “Dallas-Fort Worth Pike.” Through downtown it was “Front Street” on the east and “North Street” on the west. Late in 1930 the Star-Telegram in an editorial suggested that the street be given just one name: “Lancaster” in honor of the man who was transforming the street.

In 1931 the city agreed with the Star-Telegram and asked John L. Lancaster if he wanted to be a street, an avenue, a boulevard, etc. He said he preferred to be an avenue.

In 1931 the city agreed with the Star-Telegram and asked John L. Lancaster if he wanted to be a street, an avenue, a boulevard, etc. He said he preferred to be an avenue.

And that’s how Lancaster Avenue got its name.

And that’s how Lancaster Avenue got its name.

In 1945 John L. Lancaster was succeeded as president by William Vollmer. Lancaster remained chairman of the board.

In 1945 John L. Lancaster was succeeded as president by William Vollmer. Lancaster remained chairman of the board.

By the time Lancaster died in Dallas in 1962, he was no longer front page news in Fort Worth.

By the time Lancaster died in Dallas in 1962, he was no longer front page news in Fort Worth.

But he was in his hometown of Jackson, Tennessee.

But he was in his hometown of Jackson, Tennessee.

John Lynch Lancaster, who resurrected an iron Lazarus and in so doing transformed his namesake street and helped bring Fort Worth out of the Depression, is buried in Grove Hill Memorial Park in Dallas.

John Lynch Lancaster, who resurrected an iron Lazarus and in so doing transformed his namesake street and helped bring Fort Worth out of the Depression, is buried in Grove Hill Memorial Park in Dallas.

You do great work. I enjoy reading it

Thanks, Christy.