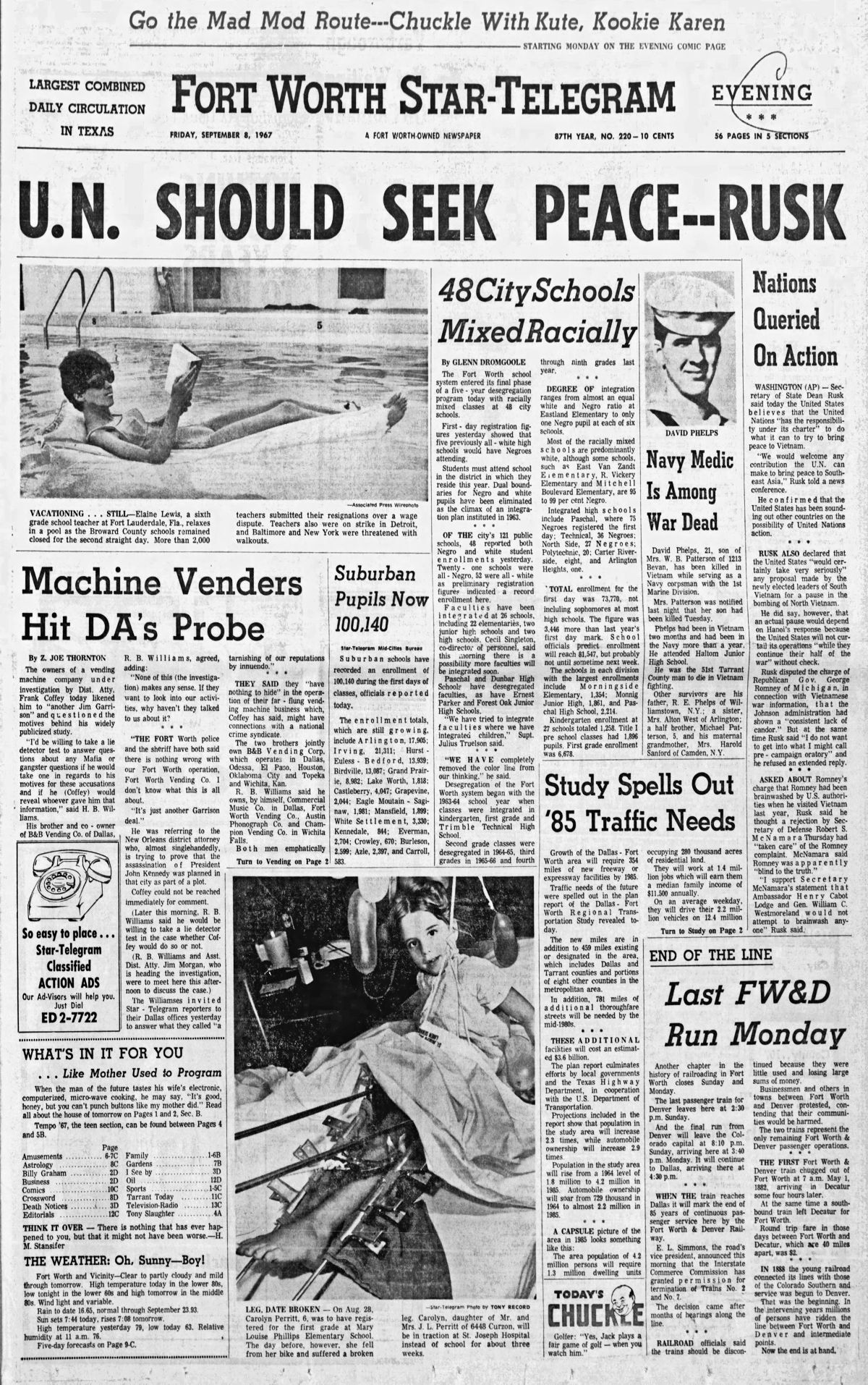

On September 8, 1967—fifty-five years ago today—the Fort Worth school system completed the process of integrating all twelve grades as African-American students enrolled in five previously all-white high schools.

This milestone was, in a larger sense, centuries in the making, of course. In a smaller sense it was eight years in the making:

In 1959 two African-American families put their foot down.

Eight years later the feet of 12,962 others shook the earth.

In 1959 Arlene Flax, age six, had plenty of white playmates at Carswell Air Force Base, where her father, Technical Sergeant Weirleis Flax, was stationed. But as the Flaxes prepared for Arlene to enter the first grade in September, they knew that when Arlene and her white playmates boarded a school bus, the white children would be dropped off at nearby Burton Hill Elementary School. Arlene would stay on the bus until it reached Como Elementary School on Horne Street almost twice as far away.

Arlene asked her father why she couldn’t attend Burton Hill Elementary with her white friends.

Weirleis Flax later said, “Arlene didn’t understand it, and I had no explanation. . . . It really ticked me off.”

On September 8, the first day of school, Flax and his wife took Arlene to Burton Hill school, where Flax stepped up to Principal James Smith and asked to enroll Arlene.

That same morning Mr. and Mrs. Herbert C. Teal of 1100 West Belknap Street took their six children to John Peter Smith Elementary School, 715 West 2nd Street, where Teal stepped up to Principal Joe McGee and asked to enroll his children.

The Star-Telegram wrote that the two principals told the two sets of parents that they would have to take their children “to Negro schools according to the Board of Education’s continued policy of operating segregated schools” (Como Elementary School for the Flaxes; George Washington Carver Elementary School, 1210 East 12th Street, for the Teals).

The Star-Telegram wrote of the two encounters: “There was no demonstration or violence, and neither family entered a protest.”

James Smith, principal of the Burton Hill school, said Sergeant Flax “just wanted to enroll the little girl in the first grade in our school, and I explained to him that we were to proceed according to the board’s decision on segregation this year.”

“He was quite nice,” Smith said of Flax.

Likewise, Principal McGee said Teal “didn’t make any comment or protest other than ‘if that’s the way it is, that’s the way it’s got to be.’”

Or not.

When the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People learned what the Flaxes and Teals had attempted to do, Dr. George D. Flemmings, president of the local chapter, called the refusal of the Teals’ request “unfortunate” and a “deliberate attempt to violate the order of the Supreme Court,” which in its Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision in 1954 had ruled that state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional.

Flemmings congratulated the Teals for taking a step forward.

“Personally, if I had children and was living far away from a school, I’d like to go to the school nearest where I live. It would be to the best interests of the children.”

These maps show the relative distances between the Flax home at Carswell Air Force Base and the Burton Hill and Como schools and between the Teal home and the John Peter Smith and George Washington Carver schools. The Teals lived seven blocks from John Peter Smith. To get to George Washington Carver, the Teals had to cross downtown and Interstate 35W.

Three weeks after taking those first small steps, the Teals and Flaxes took the next step. The NAACP filed in U. S. District Court a suit “asking a speedy temporary injunction and judgment on final hearing desegregating all Fort Worth public schools.”

The Star-Telegram wrote that the suit was filed on behalf of the Teal and Flax children “but includes ‘all other Negro minors similarly situated’ as a class of persons ‘segregated and discriminated against because of race and color.’”

Defendants included school board President W. S. Potts, Superintendent J. P. Moore, and the principals of the Burton Hill and John Peter Smith schools.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “The defendants are accused of having unlawfully racially segregated schools here ‘purposefully, intentionally, and willfully.’

“Segregation of schools here is in violation of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and federal law, the petition declares. It asks that Negro children be allowed to go to schools nearest their homes.”

The suit was filed by NAACP attorneys L. Clifford Davis of Fort Worth, W. J. Durham of Dallas, and future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall of New York.

The school system filed a motion asking the court to dismiss the NAACP suit.

The Star-Telegram wrote:

“The system charged that any change in the present segregated operation during the school year would result in ‘confusion, frustration, and chaos.’

“The motion for dismissal declares that the schools’ first concern is to provide the best education possible for each child ‘without regard to race or color.’

“‘A disruption of this program during the school year is not and could not be in the best interest of either the white or colored children involved, and their educational needs could not best be served by such disruption,’ the motion states.”

Fast-forward to 1961. The Teal-Flax suit reached U.S. District Court.

The Star-Telegram wrote:

“Federal Judge Leo Brewster ruled Thursday morning that the Fort Worth Independent School District must be integrated, starting in the fall of 1962. He ordered school officials to submit a plan for making a transition to integrated schools.”

Judge Brewster said students should attend the school nearest to their home.

NAACP attorney Davis said of the ruling: “Obviously, I’m pleased. It is our hope that the people of the community will respond in an intelligent manner to problems which might arise during the period of transition.”

The Star-Telegram wrote: “Judge Brewster ordered the school district to submit ‘a plan for effectuating a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school system to begin at the 1962 fall school term and to proceed with all deliberate speed.’

“The last phrase echoes the words of the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling that the operation of segregated school systems solely on the basis of race was unconstitutional.

“‘It is the opinion of the court,’ said Judge Brewster, ‘that the Fort Worth Independent School District cannot avoid the rule in Brown vs. the Board of Education . . . and that such decision makes unconstitutional the dual system based on racial segregation.’”

The school system appealed Judge Brewster’s ruling.

But in February 1963 the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans upheld the Brewster ruling and said Fort Worth schools must integrate although probably no sooner than the start of the new school year in September.

The school board chose not to appeal again and proposed to Judge Brewster a “stair-step” process by which Fort Worth schools would integrate one grade per year beginning with the first grade in autumn 1963.

Brewster amended that proposal to include integration in autumn 1963 of adult education night classes at Technical High School, which as a vocational school enrolled students from all over the school system.

The NAACP plaintiffs in the case said they were satisfied with the proposal.

That front page shows how much integration was in the news at the time: a photo of President Kennedy addressing business leaders about integrating public facilities and a story about Arlington schools adopting a “stair-step” integration process similar to Fort Worth’s.

On August 31, 1963, five days before integration of Fort Worth schools was scheduled to begin, Superintendent J. P. Moore retired. The new superintendent, Elden Busby, said as he assumed his new job: “Immediately we face the challenge of desegregation. We shall meet this problem in the same manner that school people should meet any school problem—openly, fairly, intelligently, and with the interest of each individual child foremost in mind.”

Note that on August 31 integration again dominated the front page. Headlines read “State School Race Mixing Peaceful,” “Many Dixie Schools Integrated Quietly,” and “Six Negroes Integrate in Tarrant Areas” (Birdville and Arlington schools began their own “stair-step” process of integration). Meanwhile Alabama Governor George Wallace withdrew most state police from Tuskegee public school but refused to allow the newly integrated school to open.

George Wallace aside, the headlines must have been reassuring to the adults involved in Fort Worth integration: NAACP attorneys, school administrators, parents.

Then came September 4. It was time for the adults to get out of the way and let the children lead.

The Star-Telegram wrote:

“Formerly all-white elementary schools opened their doors to Negro first graders Wednesday morning as Fort Worth became the last major city in Texas to integrate its public schools.

“Early indications were that there would be no incidents.

“At midmorning, Assistant Police Chief R. R. Howerton said integration was proceeding without disturbance. He said policemen would keep a close watch on the schools until noon but that no trouble was expected.”

Twenty-one African-American first-graders, some dressed for a special occasion, some holding the hand of their mother, climbed the front steps and walked into the dark hallways of previously all-white schools.

Twenty-one students. That’s forty-two feet taking the next step. The earth didn’t shake, but it trembled a tad.

In 1964 Fort Worth set an enrollment record with 72,290 students as kindergartens and second-grade classes were integrated. Ninety-three African-American students entered previously all-white schools. Technical High School also admitted African Americans of high-school age.

In 1965, after two years of integration the process was proceeding so smoothly that the school board voluntarily accelerated its pace of integration: No longer would integration be achieved in single steps—one grade per year. In 1965 grades three through six were integrated.

Meanwhile the system set another enrollment record as more than eight hundred African Americans attended previously all-white schools.

In 1966 all three grades of junior high were integrated. Previously all-white junior high and elementary schools enrolled a total of 1,002 African Americans.

On September 8, 1967—the first day of the new school year—African Americans entered five previously all-white high schools as Fort Worth’s schools were integrated through the twelfth grade. An integration process originally scheduled to take twelve years had taken only five.

On September 8, 1967—the first day of the new school year—African Americans entered five previously all-white high schools as Fort Worth’s schools were integrated through the twelfth grade. An integration process originally scheduled to take twelve years had taken only five.

A total of 6,481 African-American students enrolled in mixed-race schools in 1967.

That’s 12,962 feet making the earth shake, if only metaphorically, as they took the final steps of a journey that two families had begun eight years earlier.