He spent most of his career in the buttoned-down, by-the-book world of civil law but nonetheless played a role in two of the most memorable criminal cases in Fort Worth history.

William Capps was born in Livingston, Tennessee in 1858. He was exposed to the legal profession at an early age, working as a messenger boy for Confederate general and attorney William Cullom.

William Capps was born in Livingston, Tennessee in 1858. He was exposed to the legal profession at an early age, working as a messenger boy for Confederate general and attorney William Cullom.

As was common at the time, Capps worked on a farm during the summer and attended school during the winter. As Capps was getting his own education, the Star-Telegram later wrote, “the big boys of the Dug Hill school” in Putnam County “ran off their teacher, a brawny young man of twenty-five. One day the teacher went out to get a drink of water and never came back.” William’s grandfather, who was a trustee of the Dug Hill school, told William he could have the job if he thought he could manage the oversized scholars. The salary of $25 a month and the perk of being able to board with students’ families appealed to William.

When Capps took the offer he was not quite seventeen.

He later admitted that he had felt some trepidation when he entered the little log schoolhouse on the first morning and saw that several of the students were young men four or five years older than he was. But he managed his students without once resorting to force.

That experience—controlling an imposing crowd—would serve Capps well nine years later on a rooftop in Fort Worth.

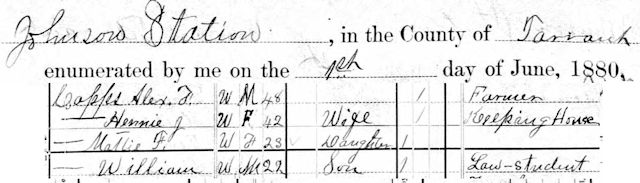

In 1878 Capps moved with his parents to Johnson Station. He continued to teach school but then returned to Tennessee to earn his law degree at Lebanon Law School. While in Tennessee Capps was offered an appointment to West Point Military Academy, but he declined.

In 1878 Capps moved with his parents to Johnson Station. He continued to teach school but then returned to Tennessee to earn his law degree at Lebanon Law School. While in Tennessee Capps was offered an appointment to West Point Military Academy, but he declined.

Returning to Tarrant County in 1881, Capps became deputy county clerk at $30 ($800 today) a month. He and county surveyor James Goodfellow bought a small wood stove and a stock of provisions and “batched” in the courthouse. They took turns cooking meals and washing dishes.

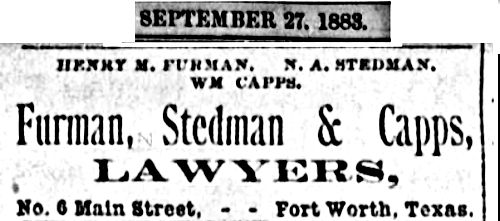

In 1882 Capps came a law partner of Henry M. Furman and N. A. Stedman.

In 1882 Capps came a law partner of Henry M. Furman and N. A. Stedman.

1885 he was elected city attorney, replacing Robert McCart.

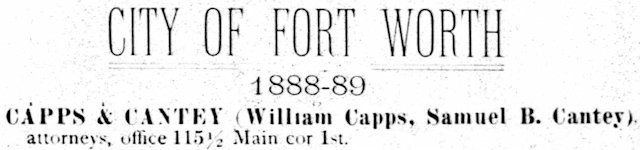

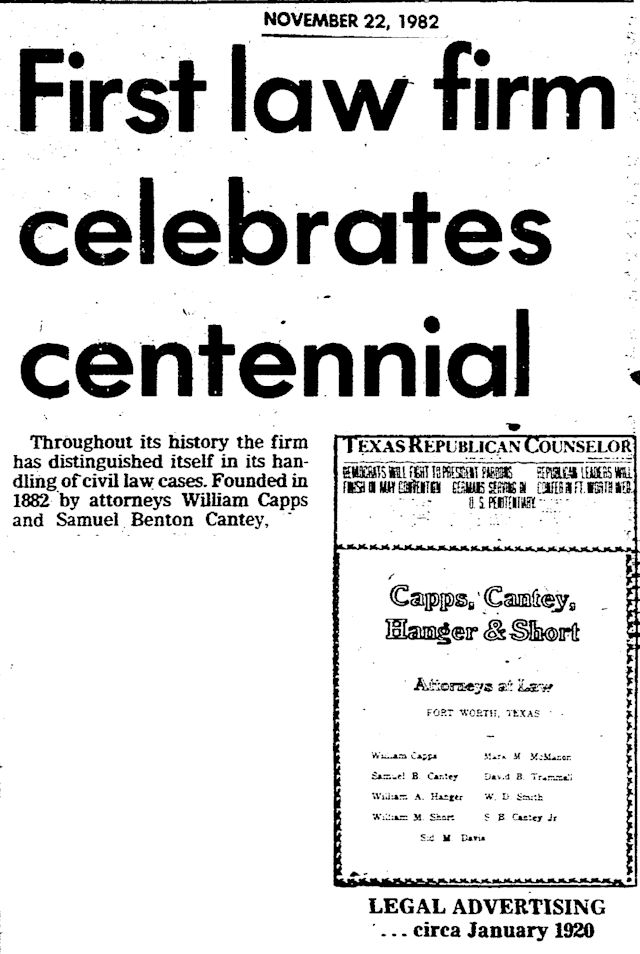

By 1888 (some sources say 1882) Capps formed a law partnership with Sam B. Cantey.

By 1888 (some sources say 1882) Capps formed a law partnership with Sam B. Cantey.

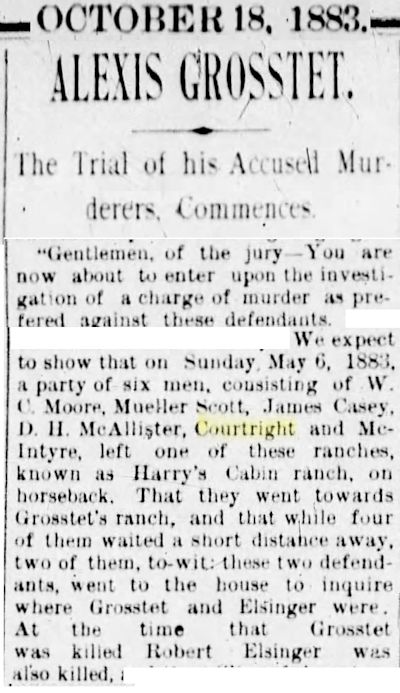

Now let’s back up to May 1883. In New Mexico former Fort Worth City Marshal Jim Courtright was a member of a posse who shot and killed two homesteaders in cold blood. While two of the posse members went on trial for murder, fugitive Courtright hightailed it back to Fort Worth and lay low.

Now let’s back up to May 1883. In New Mexico former Fort Worth City Marshal Jim Courtright was a member of a posse who shot and killed two homesteaders in cold blood. While two of the posse members went on trial for murder, fugitive Courtright hightailed it back to Fort Worth and lay low.

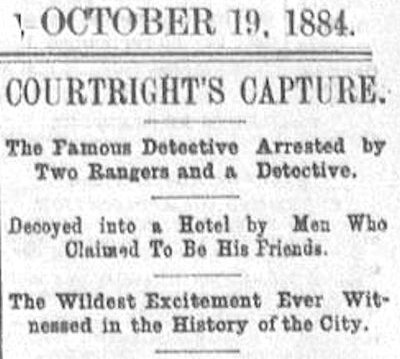

Fast-forward seventeen months. On the afternoon of October 18, 1884 Albuquerque City Marshal Harry Richmond stepped off of Texas & Pacific’s eastbound train no. 305 accompanied by two Texas Rangers, extradition papers, and a murder warrant for the arrest of Courtright.

They planned to hustle Courtright onto T&P’s westbound train no. 301 at 8:55 p.m. back to New Mexico to stand trial for murder. That timetable gave them less than four hours.

They wasted no time.

The New Mexico lawman and the two Texas Rangers tricked Courtright into meeting them at Ginocchio’s Hotel next to the Texas & Pacific passenger depot. They told Courtright they wanted him to identify a sketch of a wanted man they sought. Instead the lawmen arrested Courtright at gunpoint and held him in a room on the second floor of the hotel.

So far, so good.

Now all that the three lawmen had to do was hustle Courtright next door to the train depot and onto the train at 8:55 p.m. But soon word of Courtright’s arrest spread through downtown. Courtright was popular. People feared that the three lawmen would kill Courtright for the reward on his head or take him back to New Mexico to face vigilante justice. An angry mob gathered at the hotel, demanding to see Courtright, demanding that the lawmen release him.

Now all that the three lawmen had to do was hustle Courtright next door to the train depot and onto the train at 8:55 p.m. But soon word of Courtright’s arrest spread through downtown. Courtright was popular. People feared that the three lawmen would kill Courtright for the reward on his head or take him back to New Mexico to face vigilante justice. An angry mob gathered at the hotel, demanding to see Courtright, demanding that the lawmen release him.

The three lawmen allowed Courtright to stand at a window of the hotel. Each time he stood at the window and held up his manacled hands for the mob to see, “people seemed to lose all control of themselves and yelled in most exquisite abandonment, swaying and surging the while like an angry sea,” the Gazette wrote on October 19.

“Attacks on the hotel were spoken of, and the crowd was in a condition to do anything upon the word of a leader,” the Gazette wrote.

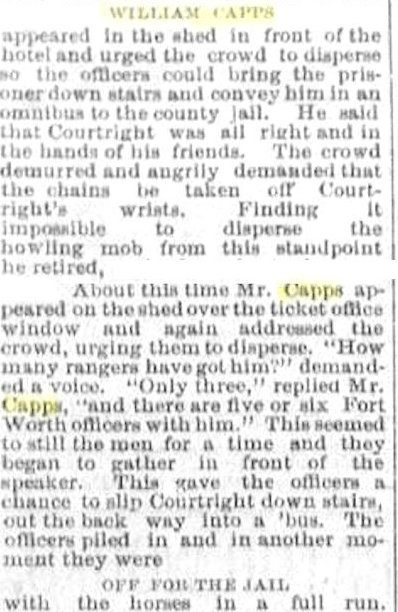

The two Texas Rangers knew that William Capps, who was Courtright’s attorney, was respected in the community. They sent for him, asked him to reason with the rawhide rabble. Leonard Sanders writes in How Fort Worth Became the Texasmost City: “Estimates of the armed mob ranged as high as two thousand.”

Capps climbed onto the roof of the train station’s ticket office and addressed the aroused citizenry milling below. Suddenly, for William Capps, now all of twenty-six, he was facing the oversized scholars of the Dug Hill classroom all over again.

Every good lawyer is also a good communicator and psychologist. Capps calmed the mob, reassured the mob that Courtright would not be harmed by the lawmen. Capps looked into the eyes of unconvinced members of the mob and appealed to the better angels of their nature. Capps no doubt recognized faces in the mob. Perhaps he addressed some individually to personalize his plea, just as he would a jury member.

Whatever his method of persuasion, Capps must have given the summation of his career that day because he held “the howling mob” in check long enough for the three lawmen to smuggle Courtright out the back of the hotel into a “flying ’bus” (omnibus) and on to the safety of the jail.

Whatever his method of persuasion, Capps must have given the summation of his career that day because he held “the howling mob” in check long enough for the three lawmen to smuggle Courtright out the back of the hotel into a “flying ’bus” (omnibus) and on to the safety of the jail.

A tentative peace prevailed.

But Jim Courtright would not be on the 8:55 train to New Mexico. The three lawmen decided not to risk trying to get their prisoner from the jail to the train while emotions were running so high among townspeople.

Instead the lawmen would make their move the next day after folks had simmered down.

But that’s another story.

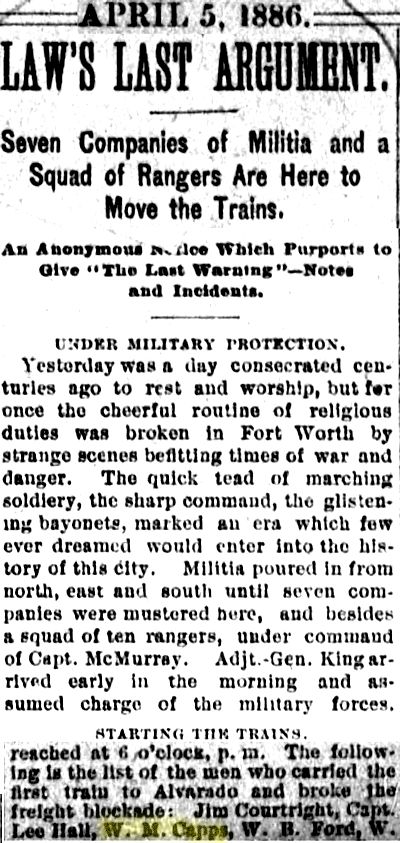

Fast-forward two years. Jim Courtright was back in town, cleared of the New Mexico killings. In April 1886 the Southwest Railroad Strike led to the Battle of Buttermilk Junction in Fort Worth: When a Missouri Pacific train attempted to break the strike, it was stopped at Buttermilk Junction by a group of men who fired upon the train’s guards, including Courtright. One deputy sheriff was killed in the shootout. Courtright and Capps were members of a posse formed to find the ambushers.

Fast-forward a year. Jim Courtright was making headlines again. But for the last time. On February 8, 1887 fellow gunfighter Luke Short killed Courtright in a one-sided shootout.

Fast-forward a year. Jim Courtright was making headlines again. But for the last time. On February 8, 1887 fellow gunfighter Luke Short killed Courtright in a one-sided shootout.

The Galveston newspaper reported that City Attorney William Capps “was one of the witnesses to the killing.” Capps, the newspaper said, called for the arrest of Courtright associate Charley Bull, “saying that it was a job put up to murder Courtright.” (Most accounts of the shooting do not mention Capps as a witness.)

The Galveston newspaper reported that City Attorney William Capps “was one of the witnesses to the killing.” Capps, the newspaper said, called for the arrest of Courtright associate Charley Bull, “saying that it was a job put up to murder Courtright.” (Most accounts of the shooting do not mention Capps as a witness.)

Indeed, Bull was rumored to have “fired one shot in defense of his friend [Courtright],” and Bull subsequently was arrested by officer John J. Fulford. The rumor was found to be false, and Bull was released.

Indeed, Bull was rumored to have “fired one shot in defense of his friend [Courtright],” and Bull subsequently was arrested by officer John J. Fulford. The rumor was found to be false, and Bull was released.

Luke Short at his examining trial was represented by McCart and William Capps, who had been Courtright’s attorney in 1884.

A grand jury declined to indict Luke Short for Jim Courtright’s death.

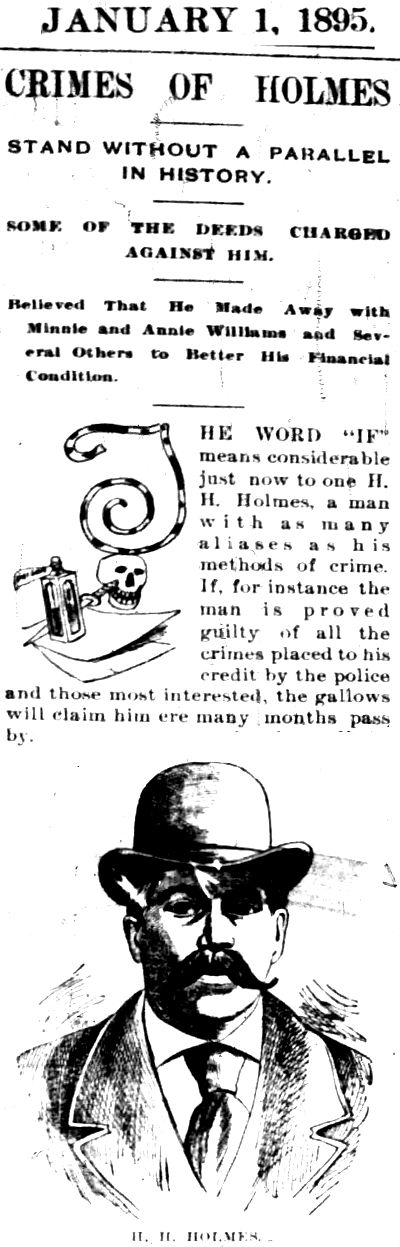

Fast-forward to 1895. As the year began America was mesmerized by the most sensational crime story in decades. Dr. Henry Howard Holmes was accused of killing, among others, sisters Minnie and Annie Williams.

Fast-forward to 1895. As the year began America was mesmerized by the most sensational crime story in decades. Dr. Henry Howard Holmes was accused of killing, among others, sisters Minnie and Annie Williams.

William Capps represented the heirs of the Williams sisters in a civil case against Holmes.

In 1893 Holmes had defrauded Minnie Williams out of property in downtown Fort Worth. On that property Holmes had begun building a hotel ominously similar to his Chicago “murder castle” when he suddenly left Fort Worth to avoid arrest for embezzlement. He was suspected of killing both sisters in addition to his partner in fraud, Benjamin Pitezel, and Pitezel’s three children.

In 1895 Capps went to Chicago on behalf of the heirs to consult with police investigating the convoluted Holmes case. Capps told a Chicago newspaper:

“There is no doubt in my mind but what Holmes murdered both the girls. Nannie [Annie], I think, was murdered within a few days after she reached the city [Chicago]. This was done, I believe, so that after he killed Minnie Williams, in whose name all the property was, there would be no one left, as both of the girls were orphans, to inquire for Minnie. I have worked on the case with detectives and have given it my entire time for a long while past, and I have arrived at the conclusion that both of the Williams sisters were murdered here in Chicago in June or July 1893.”

Capps told another Chicago newspaper: “Holmes realized that Nannie [Annie] was the heir of Minnie, and he determined to entrap the confiding Texas girl and put her out of the way. When she got here he played one sister against the other. When Nannie had been suffocated in the vault [of the murder castle], he laid his plans to get the remainder of Minnie’s estate. This was a simple matter to a man so skilled in crime. He resorted to forged deeds. He and his partner, Pitezel, and Quinlan, the janitor of the castle, were all at Fort Worth together, trying to get hold of the property. They managed to sell half of it for cash and started to put up a building on the other half. That building was designed on the same plan as the famous castle. It had the same labyrinth of dark rooms, the same kind of secret stairs, and the same repulsive exterior features. Perhaps it was Holmes’ intention to establish a murder factory in Texas, but if such was his intention he soon abandoned it, for he seized a chance to swindle some merchants and a bank out of $20,000 and left for parts unknown.”

Capps told another Chicago newspaper: “Holmes realized that Nannie [Annie] was the heir of Minnie, and he determined to entrap the confiding Texas girl and put her out of the way. When she got here he played one sister against the other. When Nannie had been suffocated in the vault [of the murder castle], he laid his plans to get the remainder of Minnie’s estate. This was a simple matter to a man so skilled in crime. He resorted to forged deeds. He and his partner, Pitezel, and Quinlan, the janitor of the castle, were all at Fort Worth together, trying to get hold of the property. They managed to sell half of it for cash and started to put up a building on the other half. That building was designed on the same plan as the famous castle. It had the same labyrinth of dark rooms, the same kind of secret stairs, and the same repulsive exterior features. Perhaps it was Holmes’ intention to establish a murder factory in Texas, but if such was his intention he soon abandoned it, for he seized a chance to swindle some merchants and a bank out of $20,000 and left for parts unknown.”

Also in 1895 Capps went to Philadelphia to interview Holmes in jail. Upon Capps’s return, the Gazette interviewed him, asking Capps his opinion of the latest news story about Holmes: The charred remains of young Howard Pitezel, son of Holmes’s accomplice Benjamin Pitezel, had been found in the chimney of a house Holmes had rented in Indianapolis. Police believed that Holmes had killed the boy with drugs and chopped up his body, which Holmes burned in a stove and hid in the chimney.

Also in 1895 Capps went to Philadelphia to interview Holmes in jail. Upon Capps’s return, the Gazette interviewed him, asking Capps his opinion of the latest news story about Holmes: The charred remains of young Howard Pitezel, son of Holmes’s accomplice Benjamin Pitezel, had been found in the chimney of a house Holmes had rented in Indianapolis. Police believed that Holmes had killed the boy with drugs and chopped up his body, which Holmes burned in a stove and hid in the chimney.

Capps said: “I think the story is true. Holmes told me eight days ago that the Pitezel boy’s remains would be found in Indianapolis.”

Did Holmes admit that he had killed the boy? the Gazette asked.

“Not by any means. On the contrary, he explained at length that he did not kill him. He said that [Edward] Hatch killed him.”

“But why should Hatch kill that boy?” the Gazette asked.

“So I asked him that. He said he [Hatch] did it at the behest of Minnie Williams. When I wanted to know why she should make such a demand, he replied instantly with a plausible explanation, as he always does.

“‘She wanted to get even with me. When I left her and took up with Mrs. Howard [a woman Holmes married using the alias “Howard”], Minnie Williams was very jealous and very angry and vowed to get even with me. She saw that if the Pitezel boy was out of the way, I would be suspected and arrested for the murder. Hatch was very much infatuated with Miss Williams, and she at once demanded that he should do that much for her.’”

And who, you ask, was Edward Hatch? He was an imaginary accomplice concocted by Holmes to blame for the murders of Howard Pitezel and his two sisters.

Henry Howard Holmes was hanged in 1896 for only one murder: that of Benjamin Pitezel.

Let us fast-forward into the new century and lighter subjects.

When William Capps was not addressing angry mobs or representing gambler-gunfighters or interviewing serial killers, he and his law firm handled mostly property and corporate cases.

When William Capps was not addressing angry mobs or representing gambler-gunfighters or interviewing serial killers, he and his law firm handled mostly property and corporate cases.

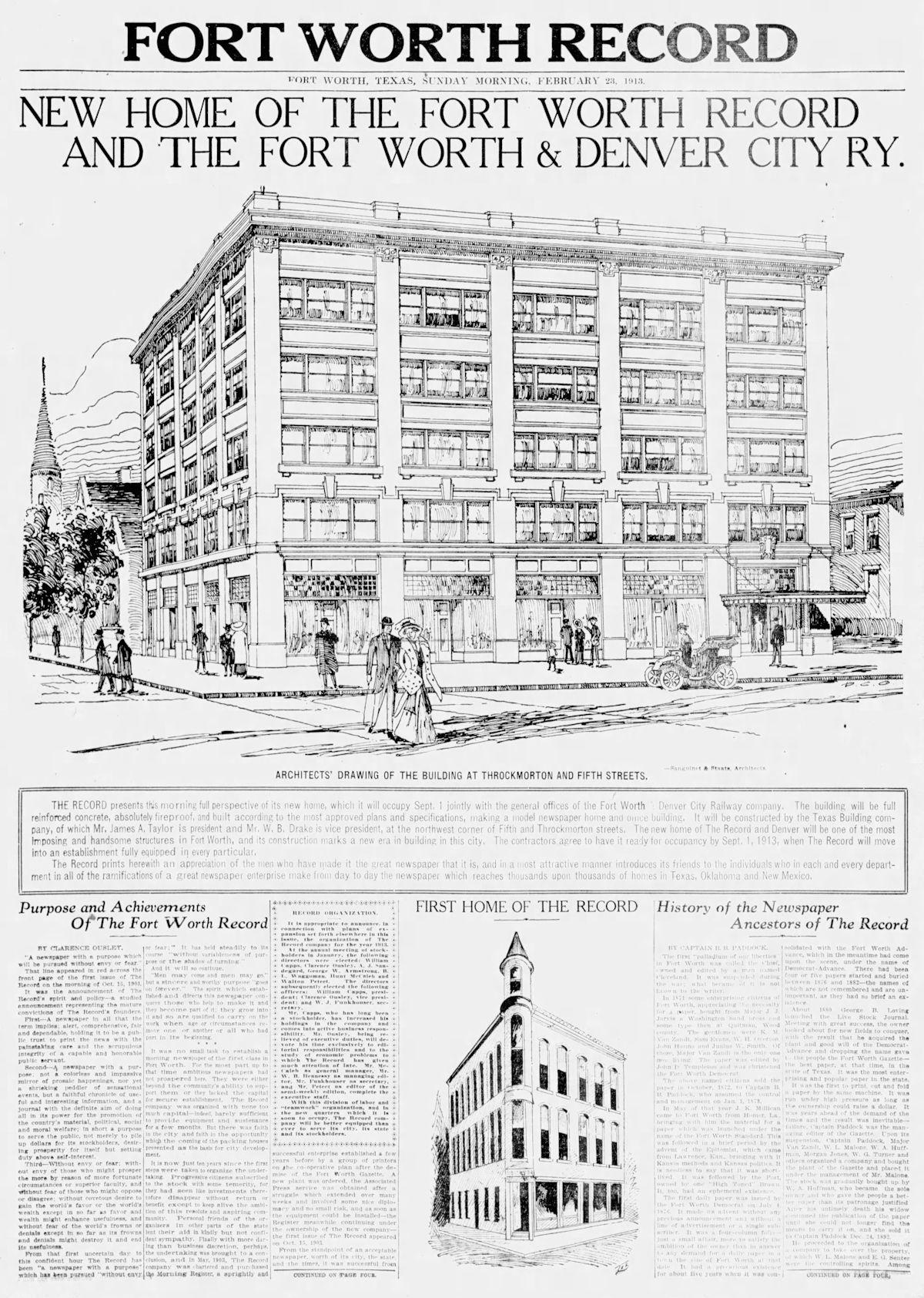

Outside the courtroom, in 1913 Capps built the Record-Denver Building, designed by Sanguinet and Staats.

Capps was president and editor of the city’s first morning newspaper, the Fort Worth Record, which evolved into the morning edition of the Star-Telegram.

The building also housed headquarters of the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad.

Capps also was a developer on the South Side (South Hemphill Heights, bisected by Capps and Cantey streets) through the Capps Land Company and the Interurban Land Company. He served as school board president, helped to bring TCU and the packing plants to town, was an incorporator of Dixie Wagon Company.

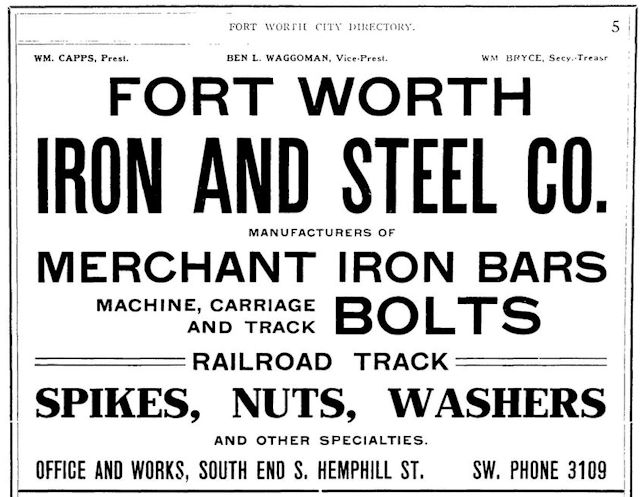

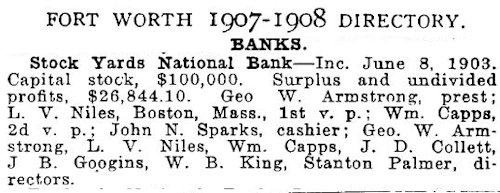

He also was president of Fort Worth Iron & Steel Company and second vice president of Stock Yards National Bank.

He also was president of Fort Worth Iron & Steel Company and second vice president of Stock Yards National Bank.

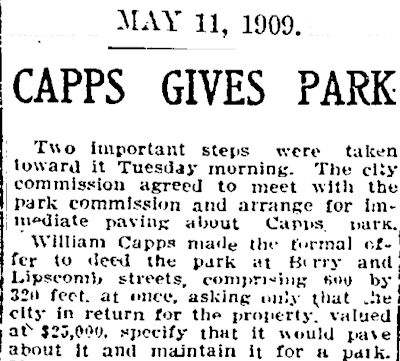

In 1909 William Capps donated land on the South Side for Capps Park.

In 1909 William Capps donated land on the South Side for Capps Park.

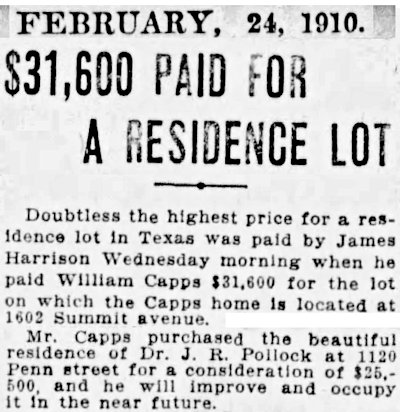

In 1910 Capps bought the grand Pollock house on Penn Street on Quality Hill for $25,500 ($628,000 today).

In 1910 Capps bought the grand Pollock house on Penn Street on Quality Hill for $25,500 ($628,000 today).

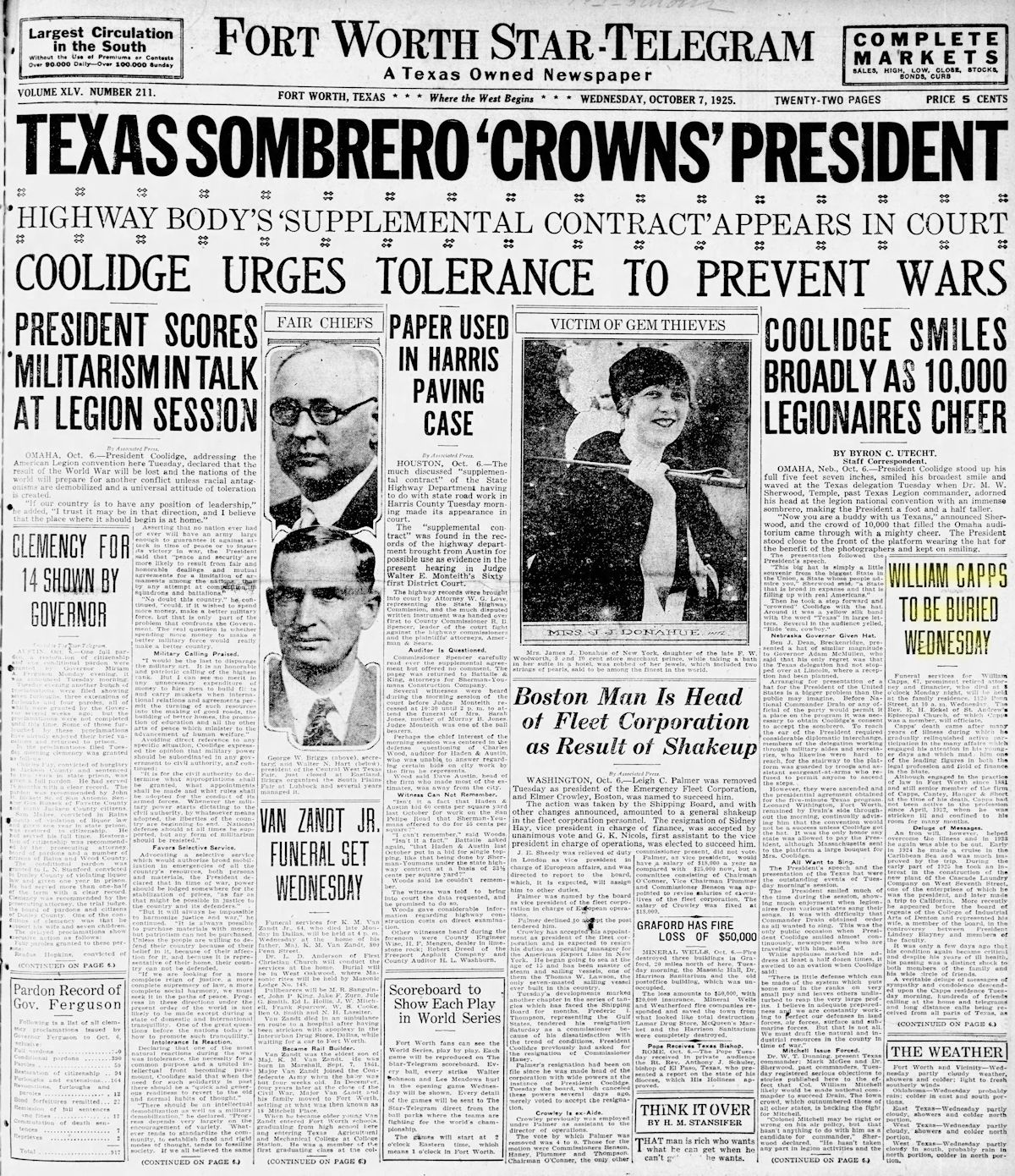

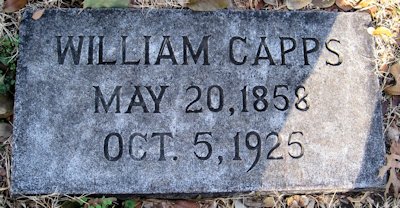

Williams Capps died in that house in 1925.

Williams Capps died in that house in 1925.

He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

The law firm that William Capps co-founded traces its founding to 1882.

The law firm that William Capps co-founded traces its founding to 1882.

The firm continues today as “Cantey Hanger.” It is Fort Worth’s oldest continuously operating law firm.

The firm continues today as “Cantey Hanger.” It is Fort Worth’s oldest continuously operating law firm.

William Capps son, Count Capps, had two sons, William and Count, Jr. Count, Jr. passed away in June, 2020. His other son, William Brooke Capps Webb, is alive and well in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

My name is anthony capps. Is there any way you would know where to get any info on his children’s names or grandchildren names. I have been told by my grandfather that his grandfather was a Texas ranger. I would love to find more info.

Anthony, I pretty much put everything I know in that post.

Find A Grave lists these four children and only one grandchild:

1 Alba Capps Lucas 1890–1949

2 Mattie Mae Capps Anderson 1892–1963

her son Frank McDaniel Anderson 1889–1974

3 Count Brooke Capps 1897–1954

4 Andrew Wilson Capps 1902–1918 (foster son)

Ancestry.com might have more.

By the way, I saw that I had posted the wrong image for his obituary. I have corrected that.

To the Writer of this article. I am Craig Capps, William would have been my 3rd Great Grandfather’s First cousin. Alexander Frank Capps (William’s Father) and John A. Capps my 3rd were brothers. Both I am currently researching the family and would like to speak to you more about this man. You have come up with information that I am hearing for the first time such as “Dug Hill School” and being a messenger for General Cullom which was his mother’s brother.

I have e-mailed you the newspaper article that contains those details.