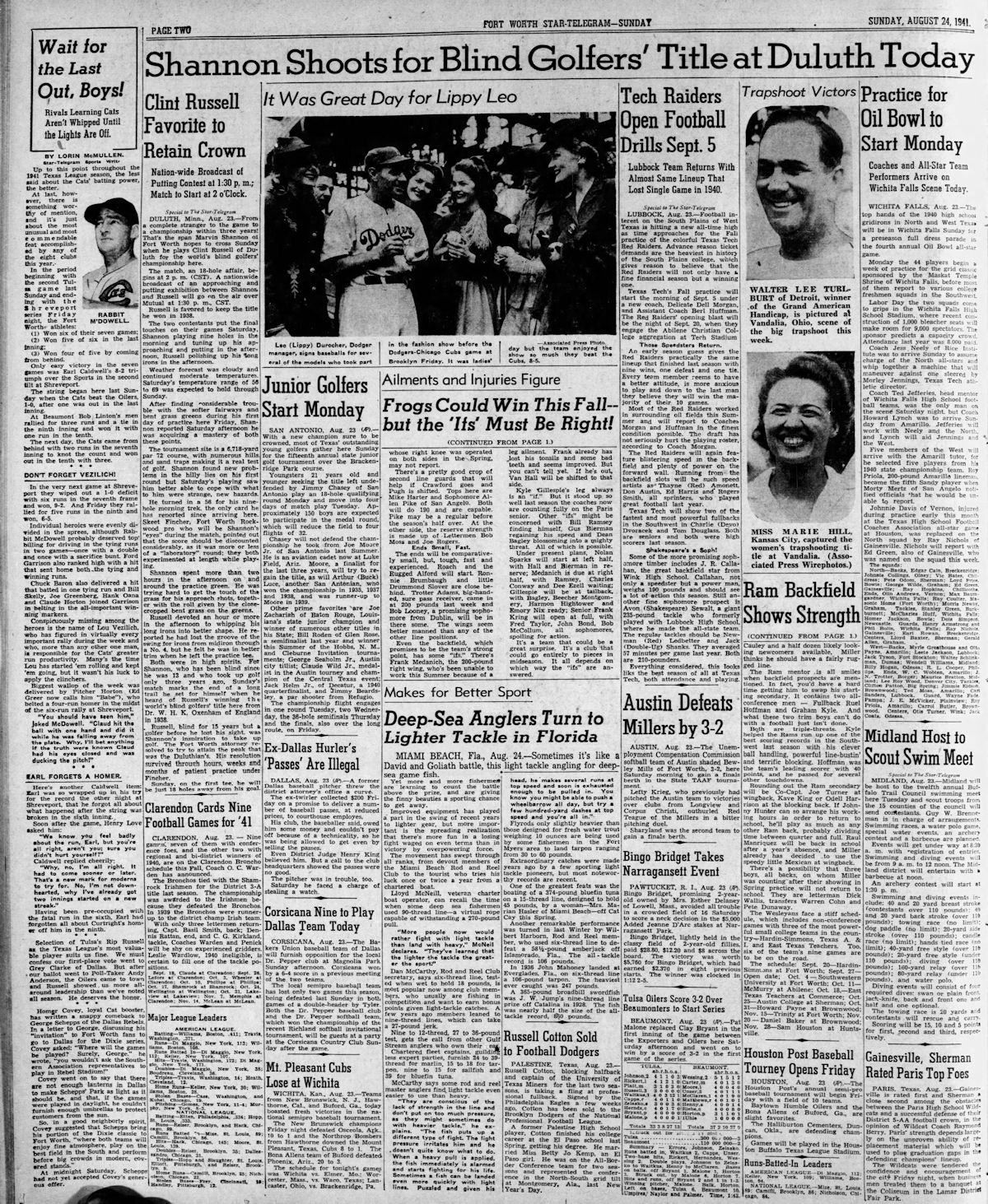

Most amateur golfers have a handicap. But few have the handicap that golfer Marvin Shannon had:

He was blind.

And during one sweet spot in time in 1941 he turned that handicap into a world title.

Marvin Boyd Shannon was born—sighted—in 1903 to Samuel David Shannon and Mary Shannon of the pioneer North Side family.

In 1908 Marvin was one of five Shannon children and guests entertained at the Shannon house in Marine. Marine was an early settlement on the North Side.

In 1908 Marvin was one of five Shannon children and guests entertained at the Shannon house in Marine. Marine was an early settlement on the North Side.

Marvin attended Denver Avenue Elementary School until a serious illness took him out of school at age twelve. By age thirteen he was blind.

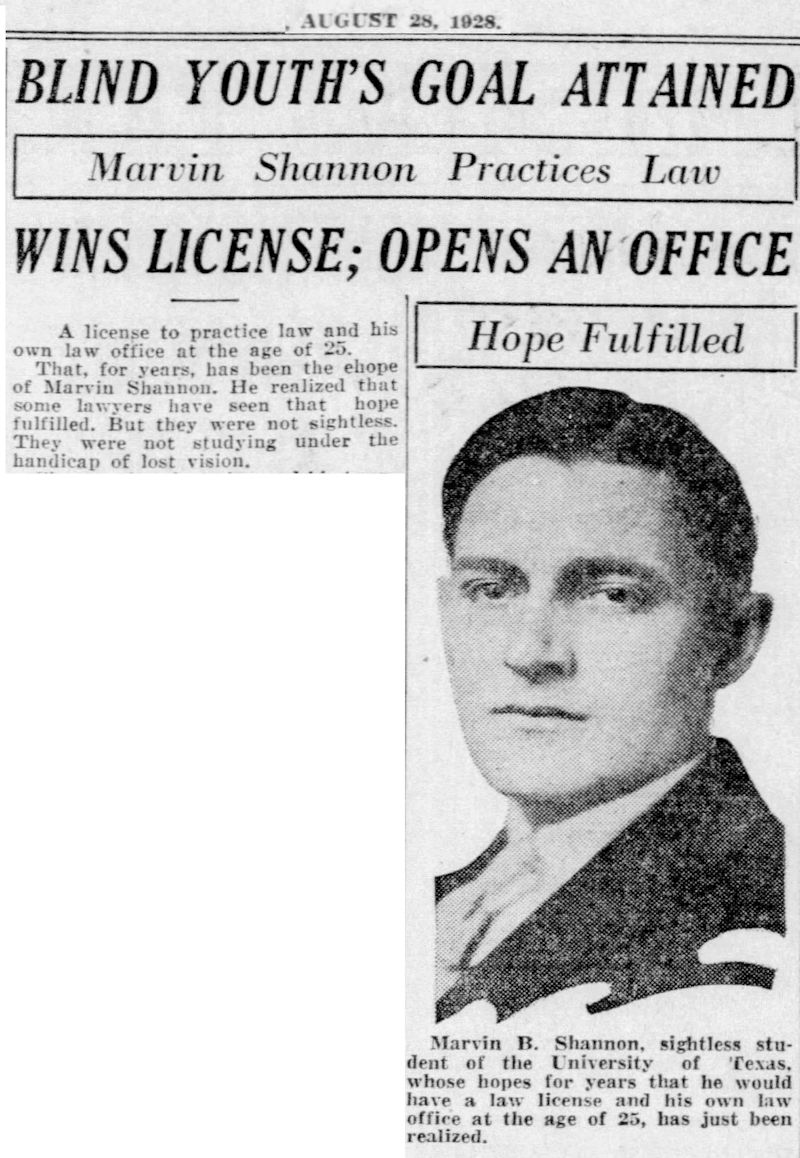

He graduated from the Texas School for the Blind and University of Texas law school. He began his law practice in 1928. He also would become an officer in the Shannon family businesses—funeral chapel, burial association, mutual aid association, life insurance company. He later would be a Fort Worth city councilman and board member of the Lighthouse for the Blind.

He graduated from the Texas School for the Blind and University of Texas law school. He began his law practice in 1928. He also would become an officer in the Shannon family businesses—funeral chapel, burial association, mutual aid association, life insurance company. He later would be a Fort Worth city councilman and board member of the Lighthouse for the Blind.

Yes, Marvin Shannon was an accomplished man despite his physical challenge. But the illness that had blinded him as a youth had left him weak as an adult.

In 1938, to restore his health, Shannon did what any blind person would do: He took up golf.

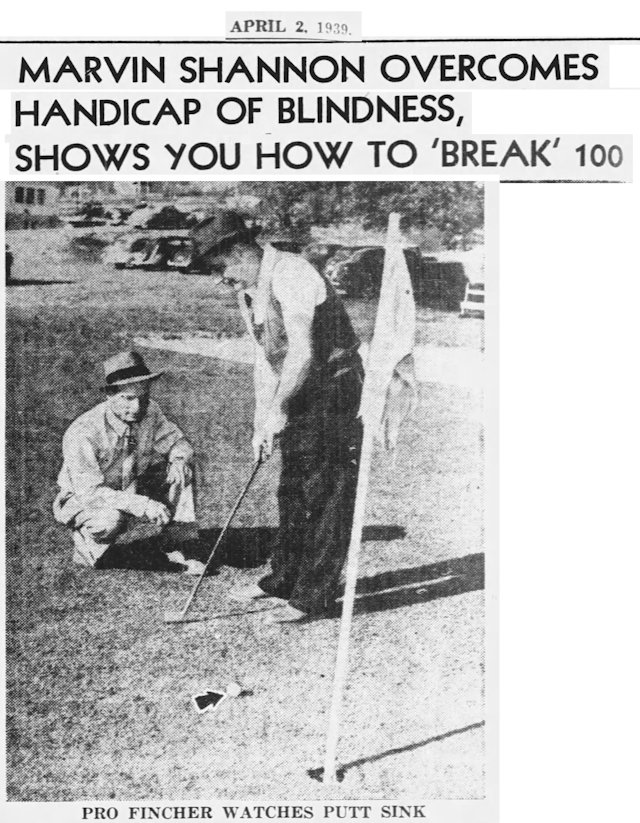

Shannon hired Skeet Fincher to teach him the game. Fincher, longtime pro or manager at Worth Hills and Z. Boaz courses, by 1938 was the pro at the new Rockwood golf course.

Not surprisingly, Fincher had never given golf lessons to a blind person.

But Shannon was determined to learn, which made Fincher determined to teach. Fincher first taught Shannon the basics of a proper swing for shots ranging from drives to chips to putts.

But Shannon could not see the ball or the tee.

For days he swung and missed.

He—and Fincher—felt like giving up.

“Skeet Fincher . . . was very patient,” Shannon recalled. “I would stand behind him and place my hands on his shoulders as he swung a club and get the idea of the body movement.”

Skeet Fincher indeed was the golf whisperer. He talked to Shannon in a low voice as he positioned Shannon to address the ball, as he positioned Shannon’s clubhead at the ball at the proper angle. He taught Shannon how to swing for various distances.

Shannon practiced every day for three months before ever stepping onto a course.

“At the end of three months I went out on the [Rockwood] course,” he recalled.

On the Rockwood course now Shannon not only could not see the tee or the ball but also could not see the fairway, green, trees, hazards, or flagpin. So, again, as Shannon addressed the ball, Fincher positioned Shannon’s body at the proper angle and positioned the clubhead at the ball at the proper angle. Fincher then acted as Shannon’s eyes, telling him the distance of the shot, the slope of the fairway or green, the presence of hazards, etc.

The rest was up to Shannon.

“My score for the first nine holes was 118,” Shannon recalled.

Then came a news story that made Marvin Shannon even more determined.

Then came a news story that made Marvin Shannon even more determined.

In Duluth, Minnesota in 1924, Clinton Russell, an amateur golfer, had lost his sight when a tire exploded in his face. In 1925 he resumed the game of golf as a blind man. By 1930 Russell was shooting lower scores—in the high eighties and low nineties—than he had as a sighted golfer. In 1938 Robert Ripley’s “Believe It or Not” syndicated newspaper feature claimed that Dr. Beach Oxenham of England was the “world’s only blind golfer.” Some of Russell’s friends took issue with that claim, challenged Ripley to sponsor the world’s first blind golf championship. Ripley accepted. On August 20, 1938 in Duluth Russell defeated Oxenham 5-4 in match play.

Inspired by that contest, Marvin Shannon became determined to reach the skill level of the world champion.

And someday to challenge the world champion.

Shannon—accompanied by Fincher—played nine holes a day, sometimes eighteen, even twenty-seven. Every day.

“I’m going out to see Doc Fincher,” Shannon would say each day as he headed to Rockwood.

At night Shannon competed in driving contests and putting contests.

After all that he soaked his blistered hands in salt water.

He developed a grooved swing and a sensitivity for position. He could sense when a shot was good or bad.

His skin became browned from the sun.

His body became stronger.

And his game became better.

In April 1939 he broke one hundred for eighteen holes at Rockwood.

In April 1939 he broke one hundred for eighteen holes at Rockwood.

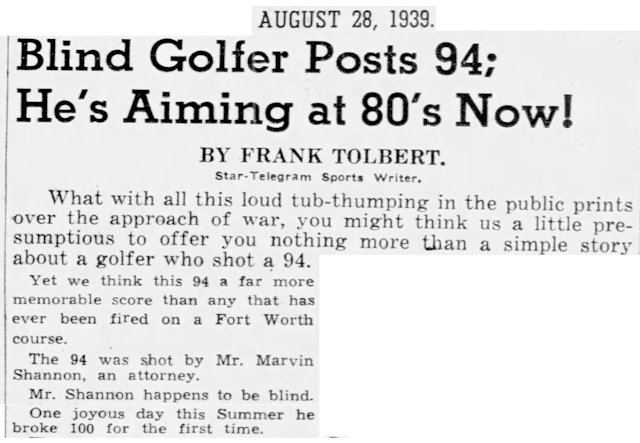

In August 1939 he shot a ninety-four.

In August 1939 he shot a ninety-four.

By early 1941 he had broken ninety at Rockwood.

He was ready.

He challenged Clinton Russell to a world championship game.

Russell consented, sent Shannon a detailed description of the Duluth course, offered Shannon the choice of playing nine or eighteen holes.

When the two met on the champ’s home course, Shannon was definitely the underdog. Shannon was a blind man who took up golf. Russell was a golfer who became blind and resumed golf. And the two were meeting on Russell’s home course.

When the two met on the champ’s home course, Shannon was definitely the underdog. Shannon was a blind man who took up golf. Russell was a golfer who became blind and resumed golf. And the two were meeting on Russell’s home course.

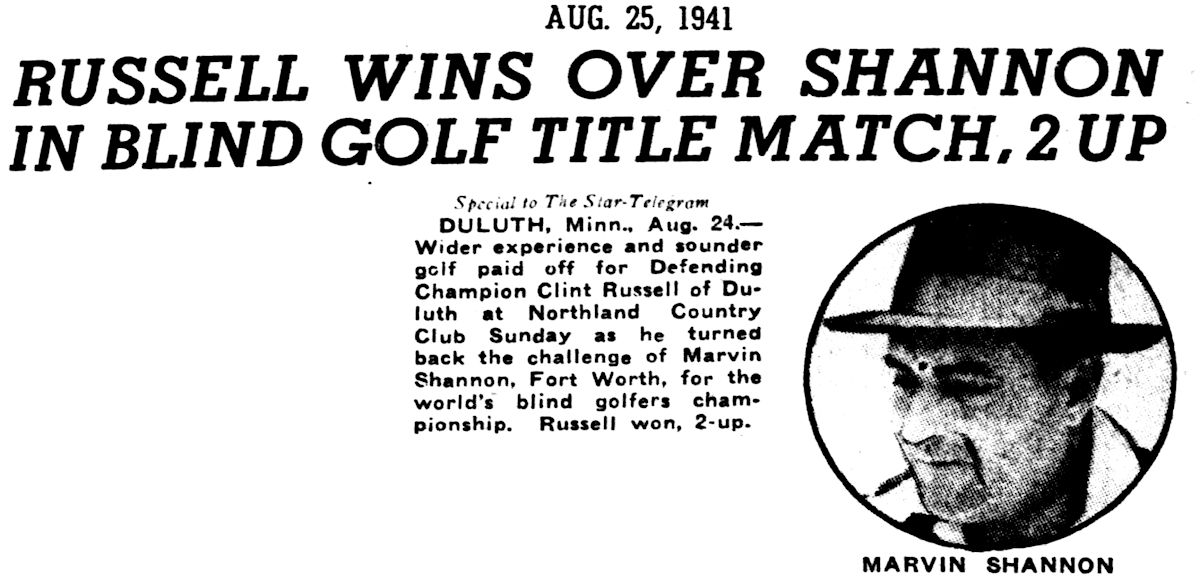

And indeed Shannon lost. As a cold northeast wind swept the course, Russell, guided by Jimmy Koehler, beat Shannon, guided by Skeet Fincher, two up.

And indeed Shannon lost. As a cold northeast wind swept the course, Russell, guided by Jimmy Koehler, beat Shannon, guided by Skeet Fincher, two up.

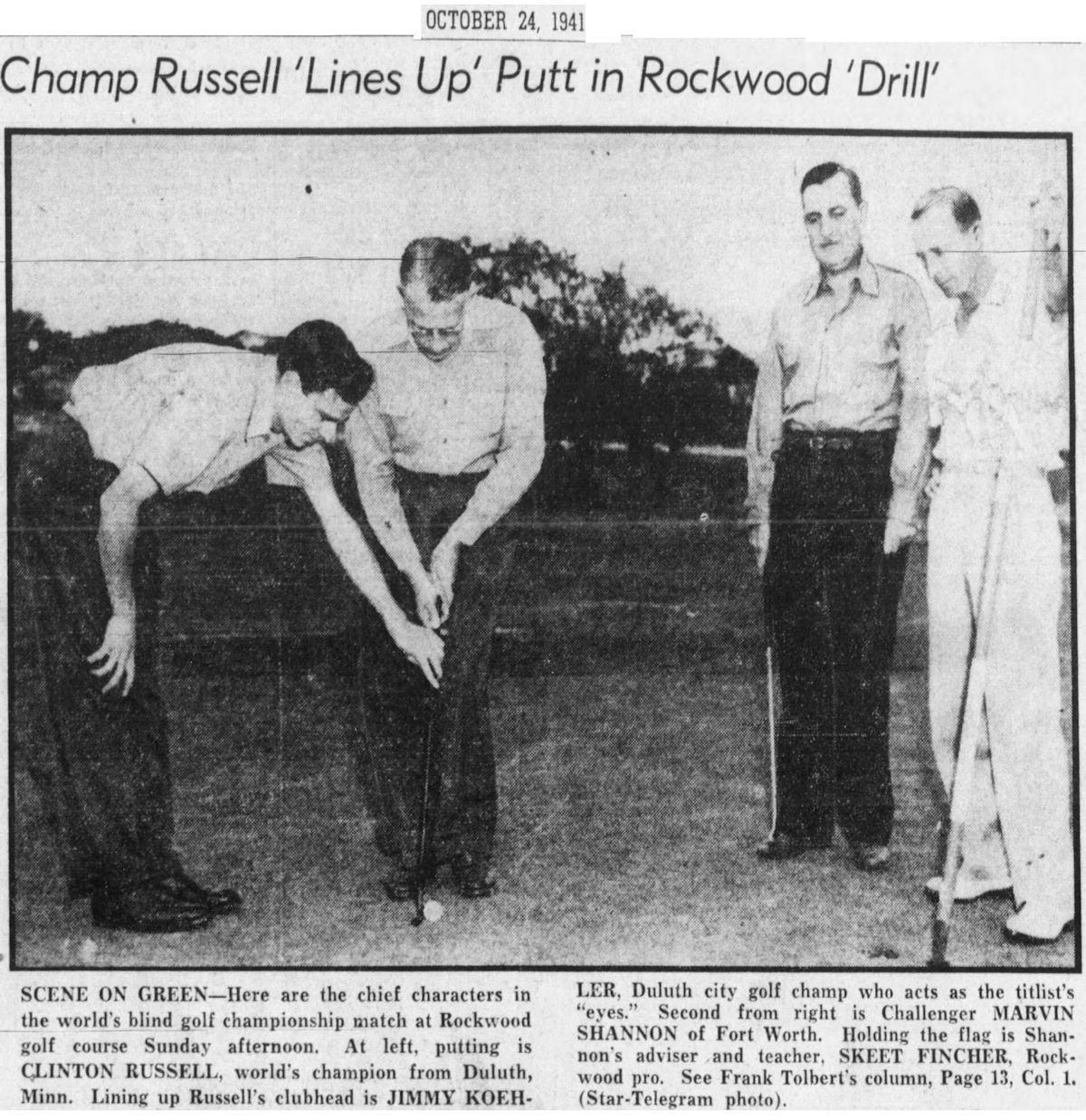

Shannon and Russell agreed to a rematch on Shannon’s home course in October.

This photo shows the two golfers and their “eyes”: Russell and Jimmy Koehler, left, and Shannon and Skeet Fincher. Russell and Koehler came into town days early to become familiar with the Rockwood course. Proceeds from the match would go to Lighthouse for the Blind.

This photo shows the two golfers and their “eyes”: Russell and Jimmy Koehler, left, and Shannon and Skeet Fincher. Russell and Koehler came into town days early to become familiar with the Rockwood course. Proceeds from the match would go to Lighthouse for the Blind.

Marvin Shannon had played hundreds of rounds on the Rockwood course. He knew the sounds of the course: a breeze rustling the trees on a fairway, the sound of cars on Jacksboro highway, the thwack of balls being hit by other golfers.

But this round was different. As the two contestants and their eyes moved around the course on October 26 they were accompanied by fifteen hundred spectators.

Now each time Shannon hit a tee shot he could gauge how well he had done by the reaction of the crowd—applause, moans, cheers.

Now each time he stroked a putt across a green, the reaction of the crowd as the ball neared the cup anticipated the outcome—hit or miss.

He could hear the feet of the spectators as they tramped from hole to hole, hear spectators whisper to each other as they watched in fascination as Skeet Fincher positioned Shannon for each shot.

The next day the Star-Telegram described the first six holes: “Shannon rapped a 200-yard drive and won the first hole with a bogey six, missing his putt for a par by inches. Marvin took the first three holes, divided the next two, and captured the sixth with a brilliant bogey four to go four up. At this juncture, charming Mrs. Russell sent a telegram to her infant granddaughter in Duluth: ‘You’d better pray. Granddaddy is four down.’”

And Granddaddy would stay down. Shannon was dominant on the course that had been his dark classroom.

Marvin Shannon won the match, eight to seven. He was the new world champion of blind golf.

At a ceremony Amon Carter presented Shannon with a large trophy, Russell with a smaller trophy.

Marvin Shannon was thirty-eight years old, with almost half his life yet to life.

Marvin Shannon would have many more professional and personal achievements. But surely one of his most cherished was that sweet spot in time when he was handed the prettiest trophy he never saw.

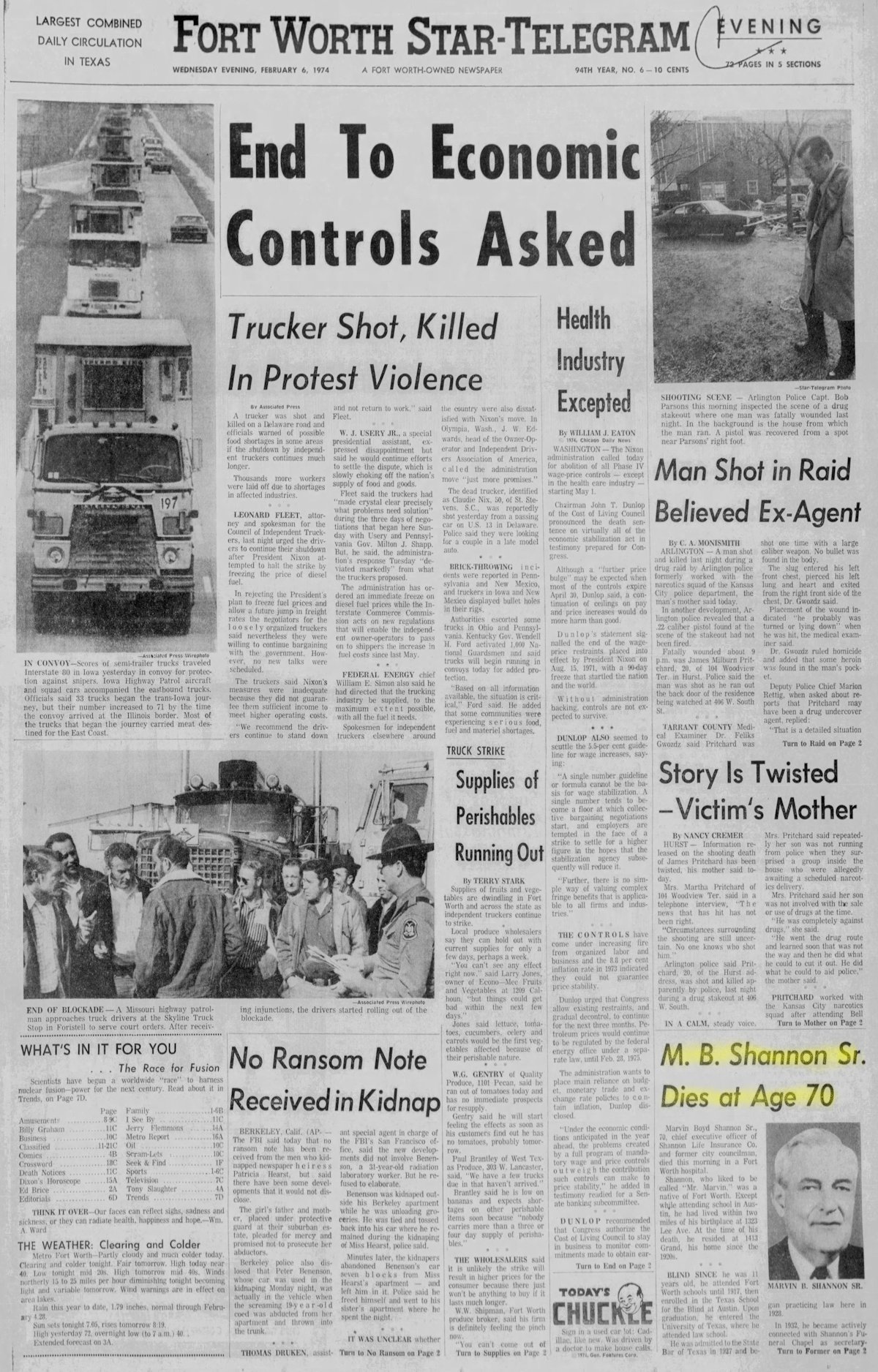

He died in 1974.

He died in 1974.

Marvin Boyd Shannon is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.