In 1911 Fort Worth was booming. It had a population of 82,167—a threefold increase since 1900. Tax valuations for the county had increased from $30 million ($932 million today) in 1900 to $88 million ($2.4 billion today) in 1910.

Banks held deposits totaling $20 million ($555 million today).

The city had almost three hundred “jobbing and manufacturing houses” representing an investment of $35 million ($938 million today).

The city was one of the railroad, oil-refining, meatpacking, and flour-milling centers of the Southwest.

And yet still Cowtown—a municipal Cassius—did have a lean and hungry look.

In fact, in February 1911 the Board of Trade—forerunner of the Chamber of Commerce—launched a campaign to bring to town still more railroads and still more factories. The slogan of the campaign:

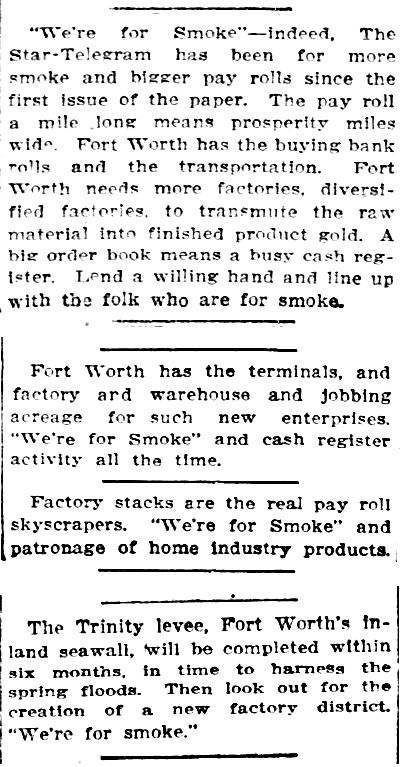

“We’re for smoke.” The campaign was “a new determination of the Board of Trade to secure factories and railroads.”

“We’re for smoke.” The campaign was “a new determination of the Board of Trade to secure factories and railroads.”

Among leaders of the campaign was B. B. Paddock, Fort Worth’s head cheerleader for growth for thirty-five years. Paddock envisioned smoke giving Fort Worth a population of two hundred thousand by 1920. By 1911 Paddock had been joined by Cowtown’s future head cheerleader: Amon Carter of the Star-Telegram.

Carter’s newspaper peppered its editorial pages with snippets that reminded readers that smoke means bigger payrolls. “The pay roll a mile long means prosperity miles wide.”

Carter’s newspaper peppered its editorial pages with snippets that reminded readers that smoke means bigger payrolls. “The pay roll a mile long means prosperity miles wide.”

But if you and I could travel back in time to the Fort Worth of 1911, we’d probably think that Fort Worth already had plenty of smoke.

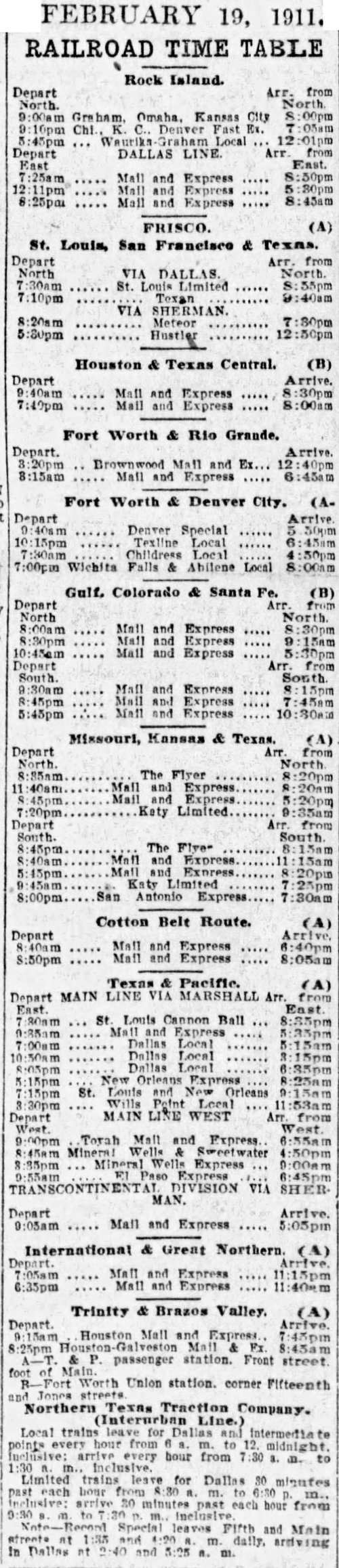

For starters, the city was served by eleven railroads. This time table is from the day the Board of Trade announced its “We’re for smoke” campaign. Dozens of passenger trains—pulled by steam locomotives—passed through town each day on tracks in all parts of town. Those trains arrived and departed at two stations located only five blocks apart downtown. Thus, the air quality downtown was especially affected by smoke. A fine layer of coal soot covered surfaces like the crepe of mourning. Not to mention the smell of smoke and oil and the bellowing and whistling of locomotives and clattering of rail cars.

For starters, the city was served by eleven railroads. This time table is from the day the Board of Trade announced its “We’re for smoke” campaign. Dozens of passenger trains—pulled by steam locomotives—passed through town each day on tracks in all parts of town. Those trains arrived and departed at two stations located only five blocks apart downtown. Thus, the air quality downtown was especially affected by smoke. A fine layer of coal soot covered surfaces like the crepe of mourning. Not to mention the smell of smoke and oil and the bellowing and whistling of locomotives and clattering of rail cars.

But to people of 1911 such assaults on the senses were all they had known since 1876. Such assaults were accepted as a necessary part of the steam-driven industrial age.

Today, 110 years after the “We’re for smoke” campaign, with hindsight and our knowledge of the effects of air pollution on individuals and on the planet, it’s easy to roll our eyes and wonder, “What were they thinking?”

But air pollution was not considered to be a problem in 1911. A search of Newspapers.com archives for the phrase “air pollution” returns only ten articles in the United States in 1911. The phrase appears in Fort Worth newspapers just once between 1900 and 1920.

To the Board of Trade in 1911, smoke meant only one thing: prosperity.

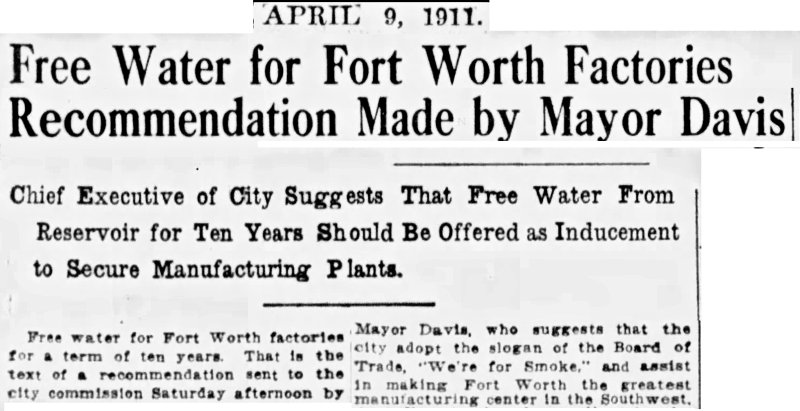

The city government quickly jumped on the “We’re for smoke” wagon. In fact, in 1911 the city was planning to impound the reservoir that would become Lake Worth. Mayor William D. Davis recommended that the city, as an incentive to factories, provide free reservoir water for a period of ten years “to every boiler that makes steam inside of the city limits.”

The city government quickly jumped on the “We’re for smoke” wagon. In fact, in 1911 the city was planning to impound the reservoir that would become Lake Worth. Mayor William D. Davis recommended that the city, as an incentive to factories, provide free reservoir water for a period of ten years “to every boiler that makes steam inside of the city limits.”

Homes were heated by coal. Boilers were fired by wood, coal, or oil, not piped natural gas. (Lone Star Gas Company had brought piped natural gas to Fort Worth only in 1910.)

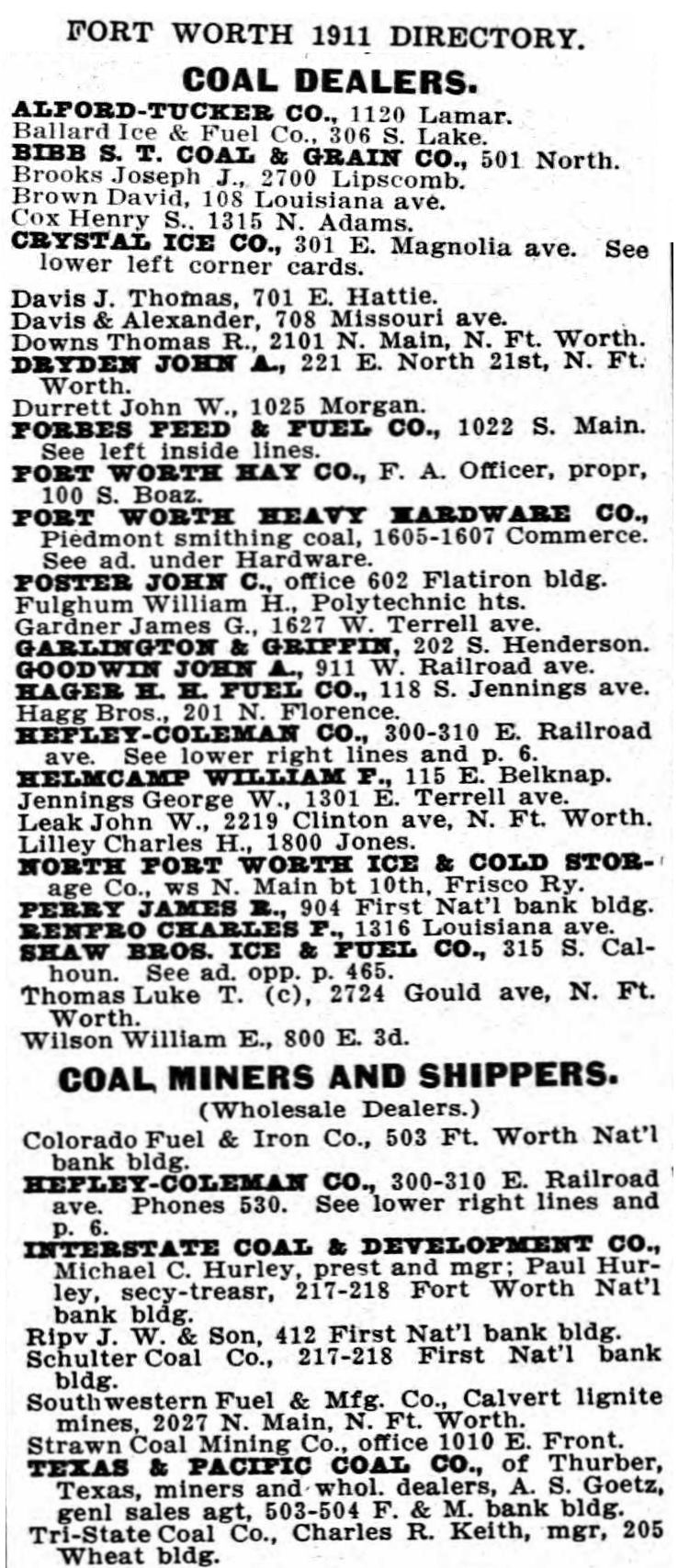

The 1911 city directory shows that coal was king. Much of that coal came from Thurber.

The 1911 city directory shows that coal was king. Much of that coal came from Thurber.

Even as the gasoline-powered internal-combustion engine became popular, everything from steam laundries to steam locomotives, from ships to air compressors used boilers to make steam. Steam-powered engines sawed timber, drilled wells, harvested crops, powered fire department pumps. Steam-powered dynamos generated electricity.

A byproduct of it all was smoke.

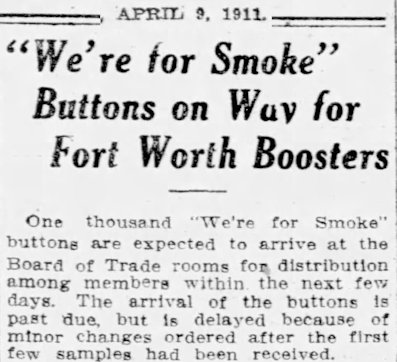

In April 1911 the Board of Trade received one thousand lapel buttons bearing the slogan “We’re for smoke” and “a silhouette of smokestacks in jet black and brilliant red.”

In April 1911 the Board of Trade received one thousand lapel buttons bearing the slogan “We’re for smoke” and “a silhouette of smokestacks in jet black and brilliant red.”

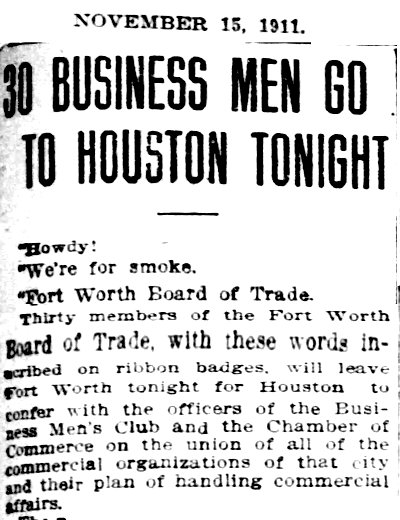

Fort Worth’s crusaders of commerce often went on train excursions to other cities to drum up business. In November thirty members of the Board of Trade went to Houston wearing ribbon badges inscribed with “We’re for smoke.”

Fort Worth’s crusaders of commerce often went on train excursions to other cities to drum up business. In November thirty members of the Board of Trade went to Houston wearing ribbon badges inscribed with “We’re for smoke.”

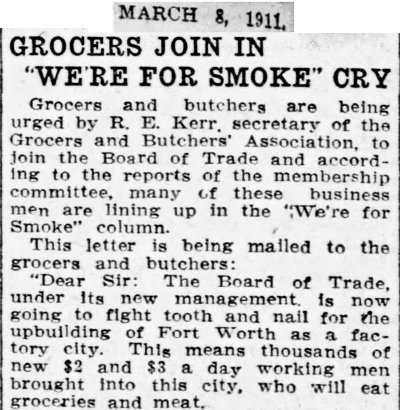

The Grocers and Butchers Association reminded its members that more factories would mean “thousands of new $2 and $3 [$55 and $83 today] a day working men,” all of whom “will eat groceries and meat.”

The Grocers and Butchers Association reminded its members that more factories would mean “thousands of new $2 and $3 [$55 and $83 today] a day working men,” all of whom “will eat groceries and meat.”

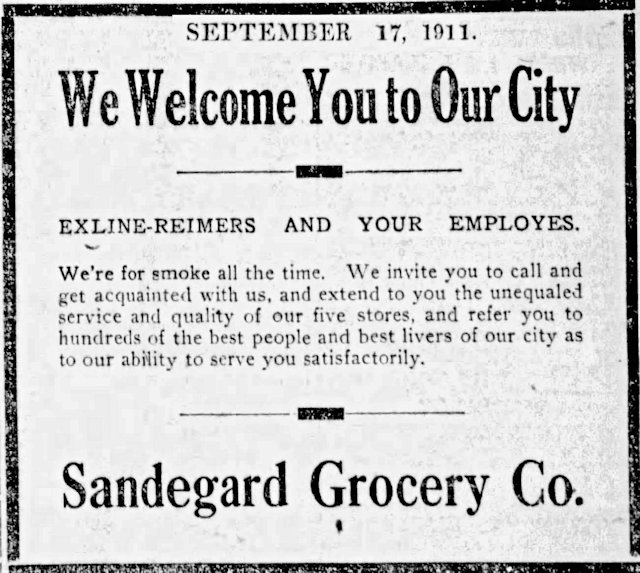

When the Reimers company relocated here from Dallas, building a huge printing plant (today the Justin boot company building) where Fort Worth High School had stood, the Sandegard grocery store chain informed the newcomers that Sandegard was “for smoke all the time” and referred them to “the best people and best livers of our city.”

When the Reimers company relocated here from Dallas, building a huge printing plant (today the Justin boot company building) where Fort Worth High School had stood, the Sandegard grocery store chain informed the newcomers that Sandegard was “for smoke all the time” and referred them to “the best people and best livers of our city.”

In 1910 Joseph Randolph Nutt had bought Fort Worth’s two electric companies and announced that he would build a new generating plant for his Fort Worth Power & Light Company. The electric plant, with its huge coal-fired dynamos, would be one of the city’s biggest producers of smoke. By 1913 its two smokestacks, 250 feet high, were easily the tallest structures in town.

In 1910 Joseph Randolph Nutt had bought Fort Worth’s two electric companies and announced that he would build a new generating plant for his Fort Worth Power & Light Company. The electric plant, with its huge coal-fired dynamos, would be one of the city’s biggest producers of smoke. By 1913 its two smokestacks, 250 feet high, were easily the tallest structures in town.

In December 1911 the Board of Trade changed its name to the “Chamber of Commerce.” Amon Carter became president. Paddock was named honorary president for life.

In January 1912 the chamber, city, and county commissioned J. J. Langever, a local sign painter and flag maker, to design an official city flag that would incorporate the “We’re for smoke” slogan.

In January 1912 the chamber, city, and county commissioned J. J. Langever, a local sign painter and flag maker, to design an official city flag that would incorporate the “We’re for smoke” slogan.

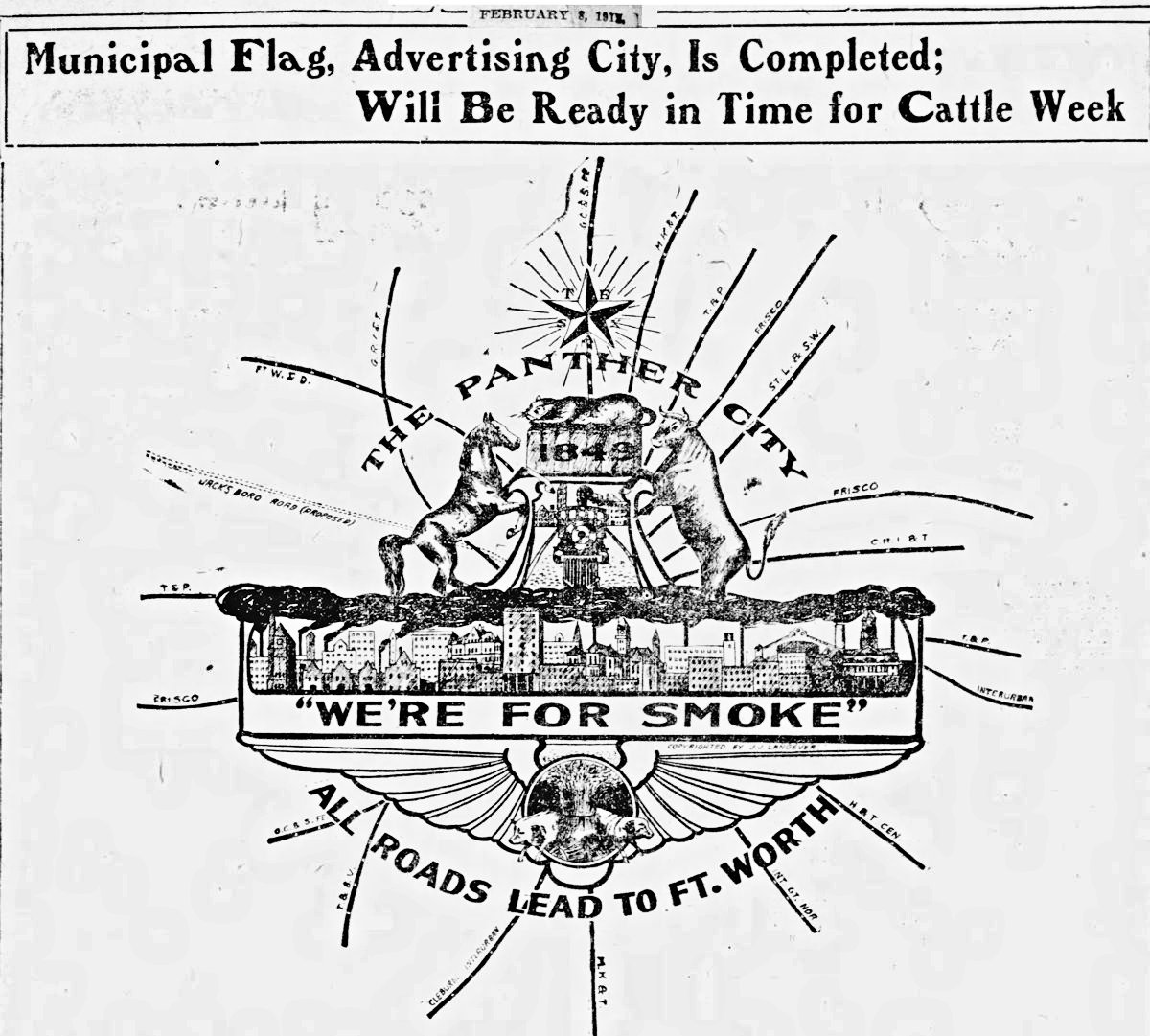

In February the Star-Telegram unveiled Langever’s design.

In February the Star-Telegram unveiled Langever’s design.

As you can see, Langever’s design is very “busy.” It is decipherable to someone seeing it reproduced in a newspaper. But to someone standing on the ground and looking up at a flag atop a flagpole, the details would be indecipherable. Let’s examine the design. On a field of white, the lines radiating from the central image represent, ala Paddock’s 1873 tarantula map, the railroad lines (and interurban lines) serving Fort Worth in 1912. At the top of the multitiered central image is the five-pointed star of Texas. Under the star are the words “The Panther City,” then the image of a panther resting on a bale of cotton that bears the founding date “1849.” Below the bale of cotton is a locomotive belching smoke as it steams straight toward the viewer. Behind the locomotive is the 1899 passenger station. All of this is flanked by a rampant horse and steer.

The horse and steer are standing fetlock deep in a cloud of black smoke that hangs over the entire city skyline. Smokestacks along the skyline pour smoke into the black cloud above.

Then comes the slogan “We’re for smoke.”

But wait! There’s more. Below is a bewinged circle containing a sheaf of wheat flanked by a hog and a sheep.

At the bottom are the words “All Roads Lead to Fort Worth.”

But wait! Langever was not through. Across this image was overlaid three red horizontal stripes so that the flag would feature red and white, which were the colors of the upcoming horse show. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

But wait! Langever was not through. Across this image was overlaid three red horizontal stripes so that the flag would feature red and white, which were the colors of the upcoming horse show. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In August 1912 after the interurban made Fort Worth and Cleburne “neighbors,” two hundred Chamber of Commerce members traveled by train to Cleburne, each waving Langever’s “We’re for smoke” flag.

In August 1912 after the interurban made Fort Worth and Cleburne “neighbors,” two hundred Chamber of Commerce members traveled by train to Cleburne, each waving Langever’s “We’re for smoke” flag.

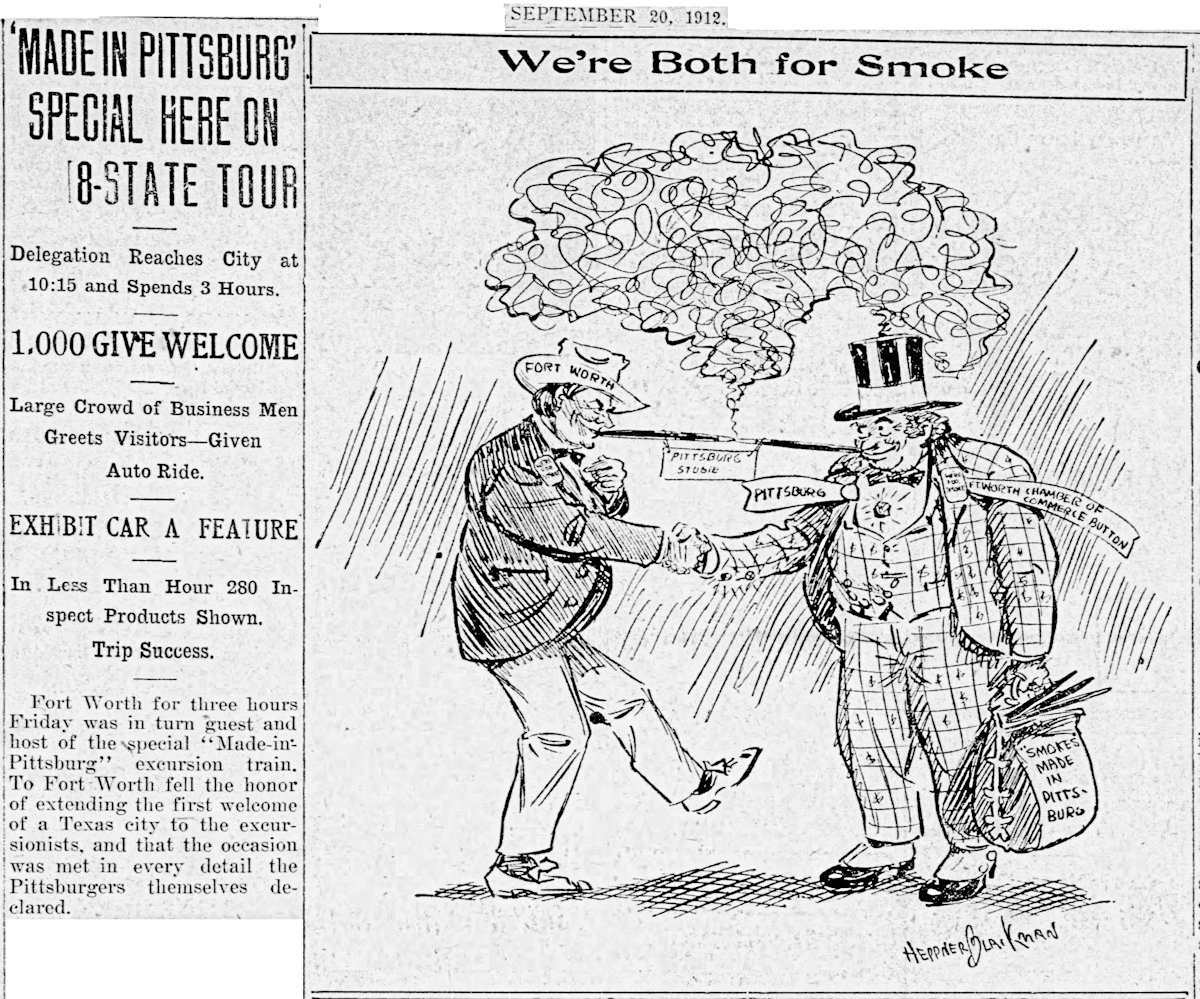

Likewise, in September a trade delegation from another town known for its smokestacks—Pittsburgh—arrived by train. The Star-Telegram page 1 cartoon was captioned “We’re Both for Smoke.”

Likewise, in September a trade delegation from another town known for its smokestacks—Pittsburgh—arrived by train. The Star-Telegram page 1 cartoon was captioned “We’re Both for Smoke.”

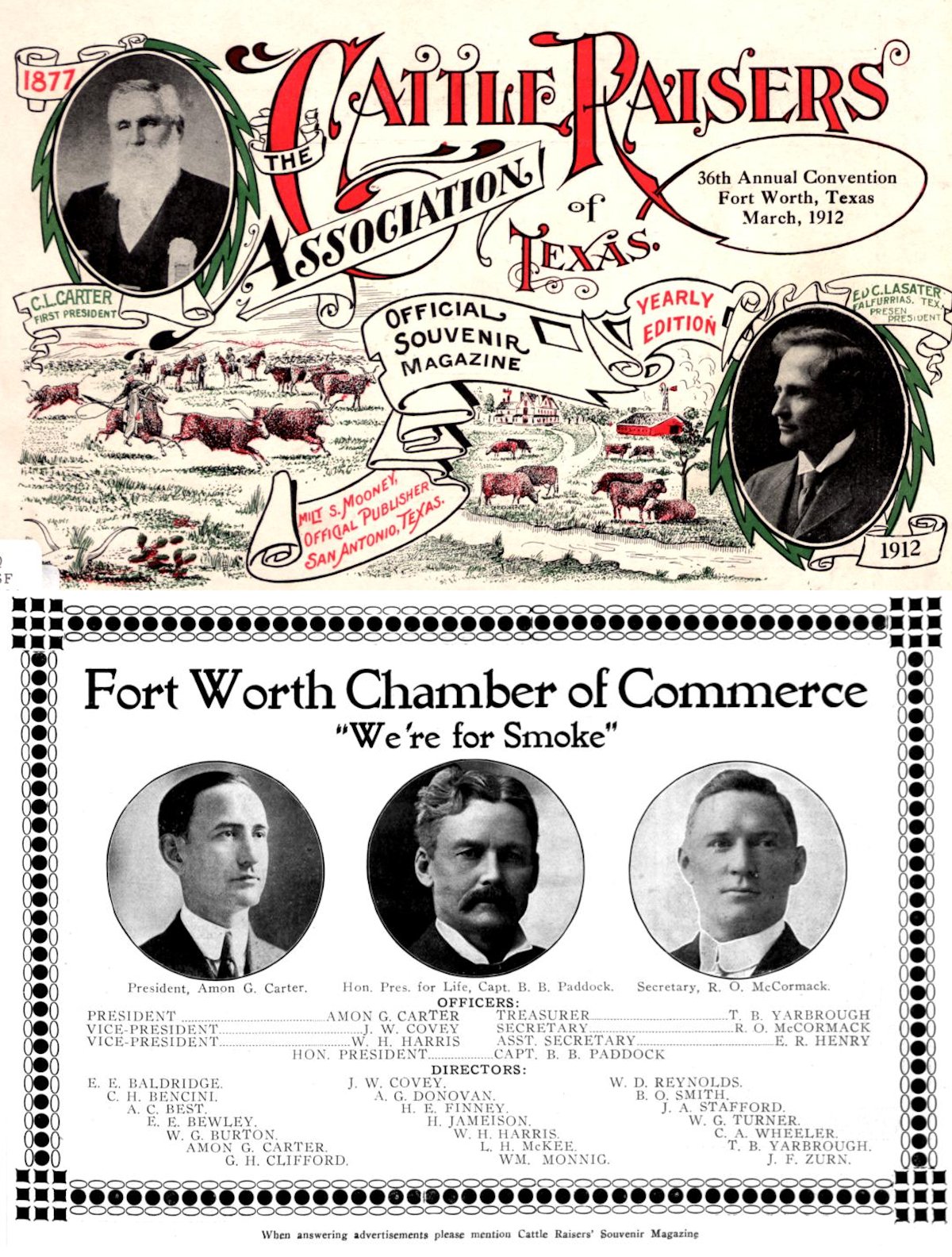

This Chamber of Commerce ad in the 1912 Cattle Raisers Association official souvenir magazine features the “We’re for smoke” slogan and photos of Fort Worth’s two head cheerleaders: Amon Carter and B. B. Paddock.

This Chamber of Commerce ad in the 1912 Cattle Raisers Association official souvenir magazine features the “We’re for smoke” slogan and photos of Fort Worth’s two head cheerleaders: Amon Carter and B. B. Paddock.

In March five hundred men smoked clay pipes decorated with “We’re for smoke” ribbons as the men enjoyed vaudeville, music, and speeches at a Chamber of Commerce event.

In March five hundred men smoked clay pipes decorated with “We’re for smoke” ribbons as the men enjoyed vaudeville, music, and speeches at a Chamber of Commerce event.

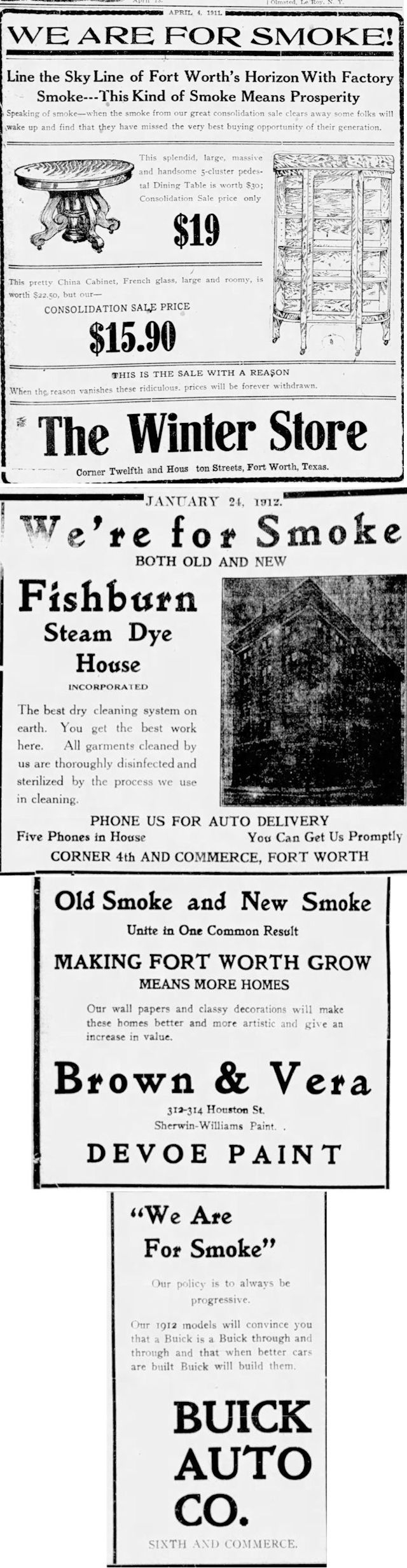

Retailers—including the Winter Store (“Line the sky line of Fort Worth’s horizon with factory smoke—this kind of smoke means prosperity”), Fishburn Steam Dye House, Brown & Vera paint store, and a Buick dealership—advertised their support for smoke.

Retailers—including the Winter Store (“Line the sky line of Fort Worth’s horizon with factory smoke—this kind of smoke means prosperity”), Fishburn Steam Dye House, Brown & Vera paint store, and a Buick dealership—advertised their support for smoke.

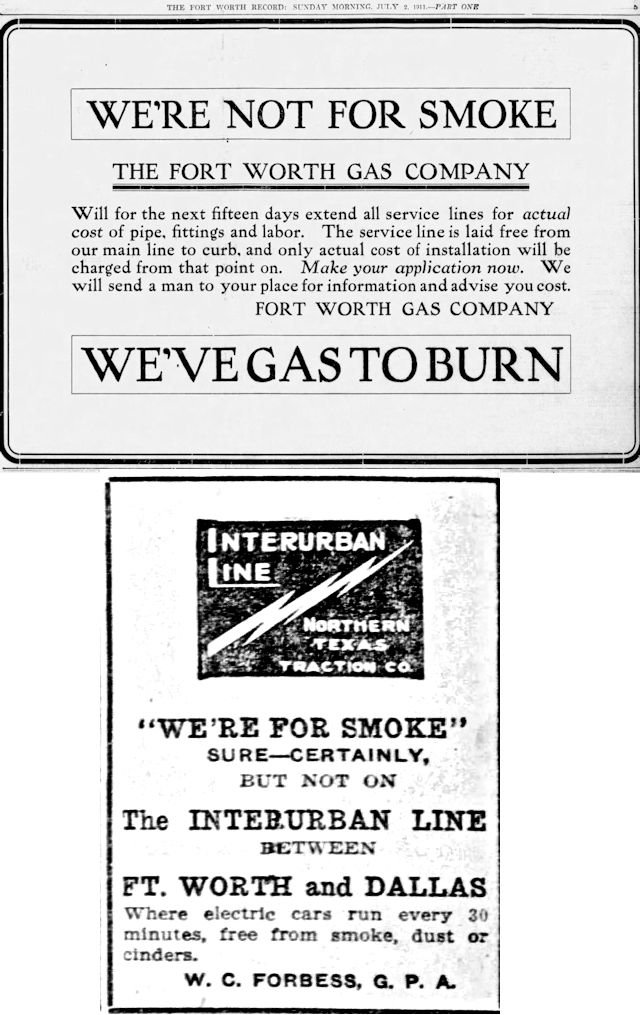

But two companies were contrarians. Well, sorta. Lone Star Gas Company reminded readers that piped natural gas was an alternative to smoke. And Northern Texas Traction Company reminded readers that although it was “for smoke,” its interurban trains were “free from smoke, dust or cinders.” Yes, the electric trains themselves created no smoke, but their electricity was generated by dynamos driven by steam at the Lake Erie generating plant. In 1912 the plant’s smokestacks constituted the skyline of Handley.

But two companies were contrarians. Well, sorta. Lone Star Gas Company reminded readers that piped natural gas was an alternative to smoke. And Northern Texas Traction Company reminded readers that although it was “for smoke,” its interurban trains were “free from smoke, dust or cinders.” Yes, the electric trains themselves created no smoke, but their electricity was generated by dynamos driven by steam at the Lake Erie generating plant. In 1912 the plant’s smokestacks constituted the skyline of Handley.

The “We’re for smoke” campaign ran about two years and faded away. Likewise, J. J. Langever’s flag soon faded away.

The “We’re for smoke” campaign ran about two years and faded away. Likewise, J. J. Langever’s flag soon faded away.

Or maybe it just couldn’t be seen through the dense prosperity.

(Thanks to Dennis Hogan for his help.)