He never lived here, never held a command here, probably never came within two hundred miles of here.

But because he lived and fought—at Chippawa, at Chapultepec, at the Cove of the Withlacoochee—and died elsewhere, you and I live here today in a place named “Fort Worth.”

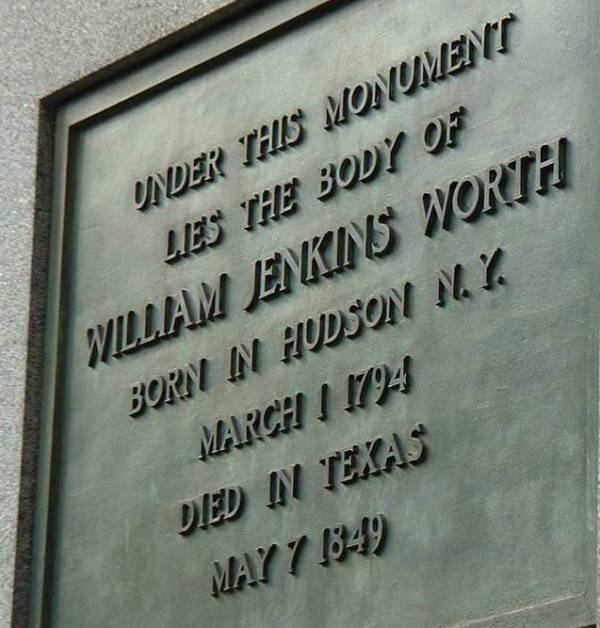

William Jenkins Worth was born in 1794 in Hudson, New York to Quaker parents. George Washington was in his second term as the first president of the United States. Young Worth received a modest education and worked as a clerk in a store.

William Jenkins Worth was born in 1794 in Hudson, New York to Quaker parents. George Washington was in his second term as the first president of the United States. Young Worth received a modest education and worked as a clerk in a store.

In 1812 America went to war against England over English violations of U.S. maritime rights. Worth, despite his Quaker heritage of pacifism, enlisted in the Army as a private at age eighteen.

A year later he was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Twenty-Third Infantry. He served as an aide to General Winfield (“Old Fuss and Feathers”) Scott.

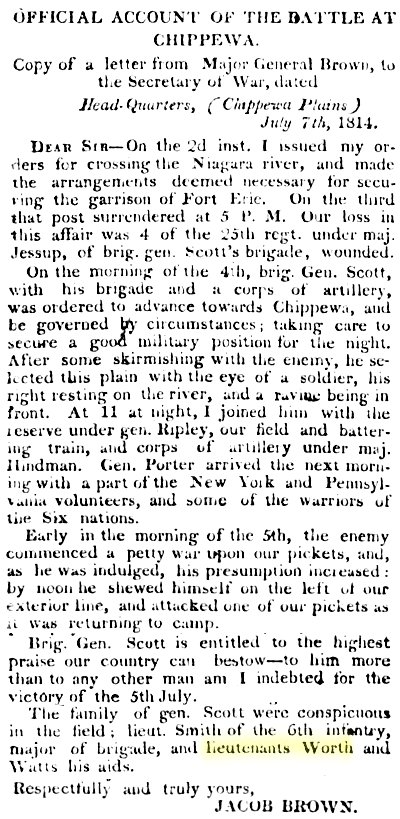

In 1814 Worth fought in the Battle of Chippawa on the Niagara River in Canada. General Jacob Brown mentioned Worth in his report of the battle. Soon after, Worth was promoted to the rank of captain.

In 1814 Worth fought in the Battle of Chippawa on the Niagara River in Canada. General Jacob Brown mentioned Worth in his report of the battle. Soon after, Worth was promoted to the rank of captain.

Then came the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, also on the Niagara River. Worth was seriously wounded by grapeshot in the thigh and was not expected to live. But after a year’s convalescence he was back in the saddle with the breveted rank of major. He would walk with a limp the rest of his life.

Then came the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, also on the Niagara River. Worth was seriously wounded by grapeshot in the thigh and was not expected to live. But after a year’s convalescence he was back in the saddle with the breveted rank of major. He would walk with a limp the rest of his life.

The painting by Alonzo Chappel depicts the Battle of Lundy’s Lane (photo from Wikipedia).

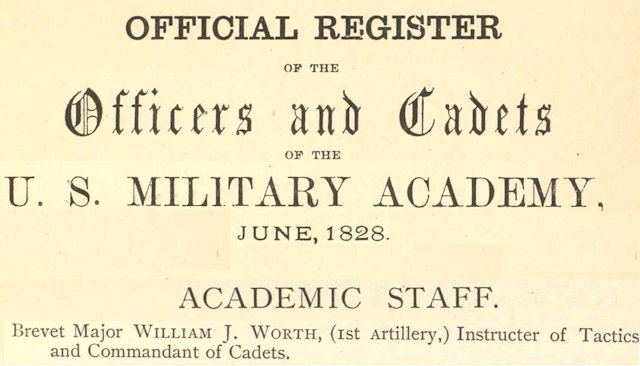

Six years later Worth, who had no formal military training, was appointed commandant of cadets at West Point military academy. He served at West Point through 1828.

Six years later Worth, who had no formal military training, was appointed commandant of cadets at West Point military academy. He served at West Point through 1828.

According to Dr. Richard Selcer in The Fort That Became a City, Worth introduced precision drill to the West Point curriculum. Among Worth’s cadets were Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee.

Douglas Southall Freeman in his biography of Lee writes: “Robert had been under Worth during the whole of his cadetship and esteemed him greatly. To him, perhaps more than to any one else, Lee owed the military bearing that was to distinguish him throughout his military career.”

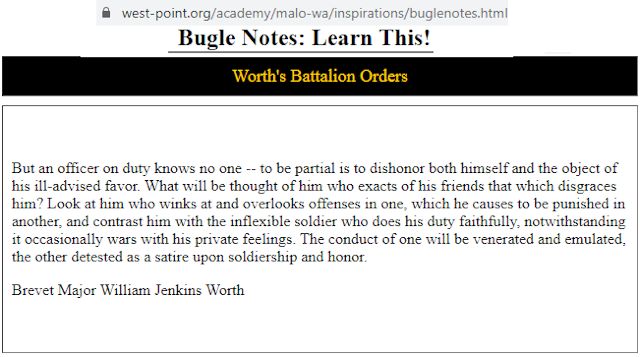

Worth’s “Battalion Orders” are inscribed in West Point’s Bugle Notes, a manual that cadets must know by heart.

Worth’s “Battalion Orders” are inscribed in West Point’s Bugle Notes, a manual that cadets must know by heart.

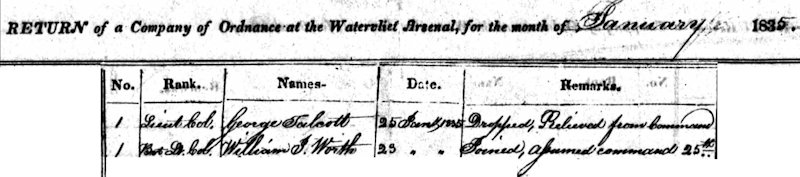

By 1835 Worth held the rank of breveted lieutenant colonel and was stationed at Watervliet Arsenal north of Albany. Watervliet is the oldest continuously active arsenal in the United States. Today it produces much of the artillery for the Army.

By 1835 Worth held the rank of breveted lieutenant colonel and was stationed at Watervliet Arsenal north of Albany. Watervliet is the oldest continuously active arsenal in the United States. Today it produces much of the artillery for the Army.

In 1838 Worth was given command of the newly created Eighth Infantry Regiment.

Three years later Worth returned to the battlefield, this time in Florida during the Second Seminole War. He replaced Brigadier General Walker Keith Armistead as commander of Army forces in Florida as federal troops fought to put down uprisings by Native Americans who were resistant to being forced to relocate to “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi River.

Edward Seccomb Wallace writes in General William Jenkins Worth—The American Murat (French marshal Joachim-Napoléon Murat):

“During the winter of 1841 Worth kept his regiment in such a state of feverish activity in pursuit of the elusive Seminoles that a song was written in the regiment, the chorus of which went

When the Colonel’s on the ground

The d—l’s to pay all around

It’s blow the trumpet, beat the drum

Don’t you see the Colonel’s come?

Don’t stand there and suck your thumb

Gods! don’t you see the Colonel’s come?”

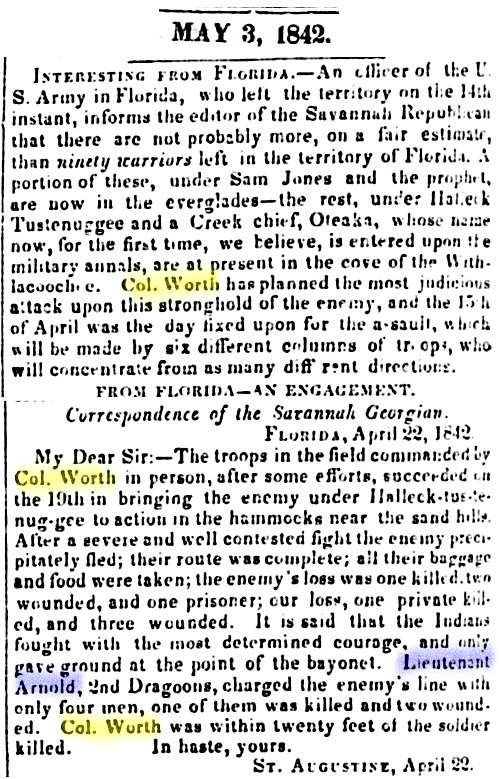

In 1842 Worth and his troops drove Seminole chief Halleck Tustenuggee and Creek chief Oteaka and their warriors out of the Cove of the Withlacoochee River. Serving under Worth was Ripley Allen Arnold, a second lieutenant four years out of West Point.

In 1842 Worth and his troops drove Seminole chief Halleck Tustenuggee and Creek chief Oteaka and their warriors out of the Cove of the Withlacoochee River. Serving under Worth was Ripley Allen Arnold, a second lieutenant four years out of West Point.

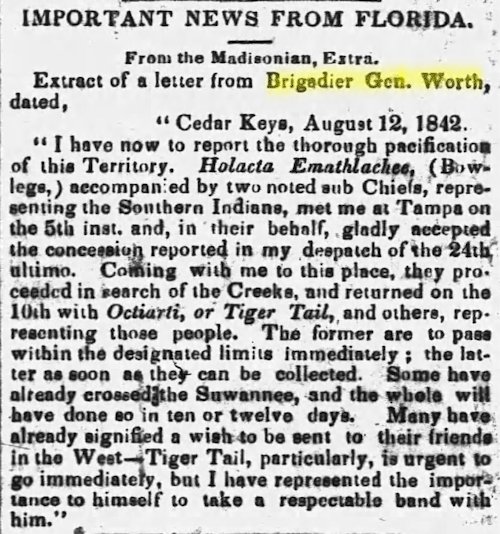

In August 1842 Worth reported “thorough pacification” of Florida. He then took ninety days of leave. While he was away, Native American attacks on Anglo settlements in Florida began again. Worth returned to Florida in November and captured and relocated more Native Americans to the west. By April 1843 only one federal regiment, the Eighth Infantry, remained in Florida.

In August 1842 Worth reported “thorough pacification” of Florida. He then took ninety days of leave. While he was away, Native American attacks on Anglo settlements in Florida began again. Worth returned to Florida in November and captured and relocated more Native Americans to the west. By April 1843 only one federal regiment, the Eighth Infantry, remained in Florida.

In November 1843 Worth reported that the few Native Americans who remained in Florida were living on a reservation and were no longer deemed a threat to the Anglo population.

Meanwhile Worth continued to rise in rank: In 1842 he had been breveted to brigadier general.

Worth’s next war, like his first war, was fought on foreign soil. In 1846 the United States and Mexico went to war because Mexico did not recognize the treaty signed by Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1836 ending the Texas war for independence. Mexico also did not recognize the 1845 annexation of Texas by the United States and considered Texas still to be Mexican territory. (“Rio Bravo” was Mexico’s term for the Rio Grande.)

Worth’s next war, like his first war, was fought on foreign soil. In 1846 the United States and Mexico went to war because Mexico did not recognize the treaty signed by Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1836 ending the Texas war for independence. Mexico also did not recognize the 1845 annexation of Texas by the United States and considered Texas still to be Mexican territory. (“Rio Bravo” was Mexico’s term for the Rio Grande.)

When the war began, according to Appleton’s Cyclopædia of American Biography, Worth “was second in command to Gen. Zachary Taylor . . ., leading the van of his army, and being the first to plant, with his own hand, the flag of the United States on the Rio Grande.”

According to Appleton’s, General Worth under General Taylor conducted the negotiations for the surrender of Matamoras in May 1846. Worth next commanded the Second Regular Division, Army of Occupation at the Battle of Monterrey in September 1846.

Joining Worth at Monterrey was young Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant, who later recalled Worth thusly: “I found General Worth a different man from any I had before served directly under. He was nervous, impatient, and restless on the march or when important or responsible duty confronted him.”

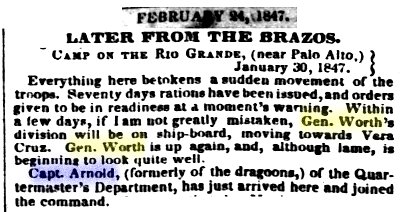

Ripley Allen Arnold, now a captain, was reunited with General Worth in January 1847.

Ripley Allen Arnold, now a captain, was reunited with General Worth in January 1847.

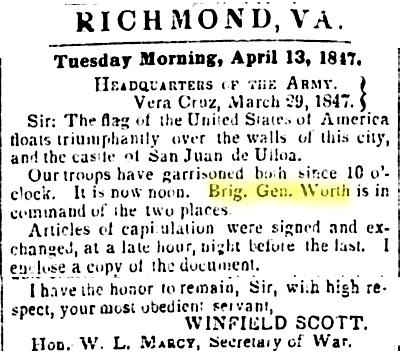

Worth also took part in the twenty-day siege of Vera Cruz in 1847. When residents of the city surrendered to heavy bombardment, Wallace writes:

Worth also took part in the twenty-day siege of Vera Cruz in 1847. When residents of the city surrendered to heavy bombardment, Wallace writes:

“[General Winfield] Scott appointed General Worth as one of the three American commissioners to confer with an equal number of Mexicans. . . . [T]he various representatives . . . came to an agreement, whereby the Mexicans surrendered the city and the fortress Ulua, the troops evacuated the city with full honors of war and were paroled, and the heavy armament should be disposed of by the treaty of peace.

“On the twenty-ninth these conditions were observed and the Mexicans marched out, between two lines of Worth’s regulars and some volunteers, and stacked their arms. Worth, who had been appointed military governor of the city the day before, received the Mexican officers with all possible courtesies and his men even shared their rations with the depressed Mexican soldiers. Then, forming his division into line, he led his men into the city with the bands playing ‘Yankee Doodle,’ ‘Hail, Columbia,’ and other favorite American tunes of the times.”

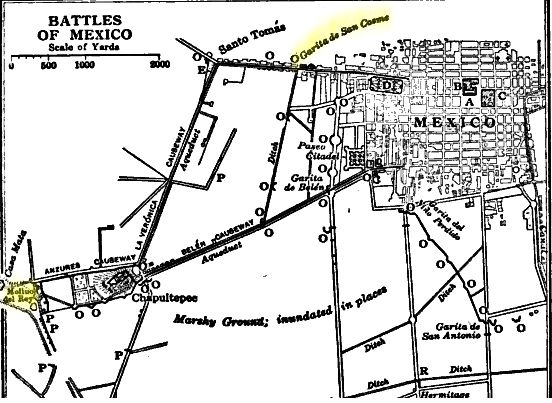

These excerpts from a newspaper war correspondent’s single dispatch in October 1847 show that Worth was nigh on to ubiquitous in Mexico. In addition to Matamoras, Monterrey, and Vera Cruz, he fought at Cerro Gordo, Contreras, Chapultepec, and Churubusco. (Robert E. Lee fought in the latter four battles.) In the clippings, note that the United States was butting cabezas with Texas’s old nemesis, Santa Anna.

These excerpts from a newspaper war correspondent’s single dispatch in October 1847 show that Worth was nigh on to ubiquitous in Mexico. In addition to Matamoras, Monterrey, and Vera Cruz, he fought at Cerro Gordo, Contreras, Chapultepec, and Churubusco. (Robert E. Lee fought in the latter four battles.) In the clippings, note that the United States was butting cabezas with Texas’s old nemesis, Santa Anna.

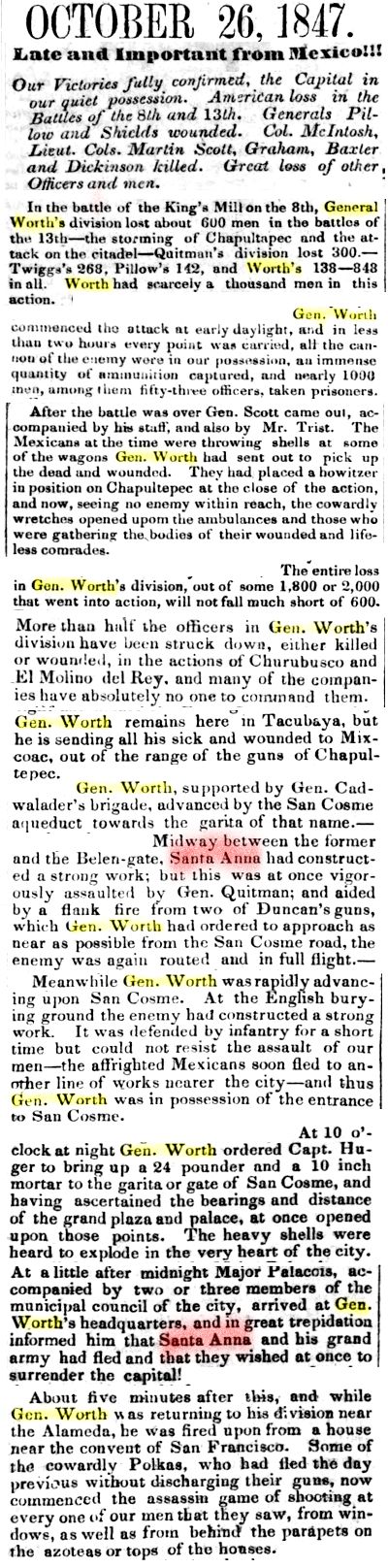

At Mexico City in 1847 Scott ordered Worth to seize the foundry at Molino del Rey just outside the city. Worth next led his troops against the Garita [Gate] de San Cosme just outside the city (Ulysses S. Grant placed small howitzers in church steeples overlooking the city). Worth’s troops were among the first to enter—and last to leave—Mexico City as the capital fell. (Map from Wikipedia.)

At Mexico City in 1847 Scott ordered Worth to seize the foundry at Molino del Rey just outside the city. Worth next led his troops against the Garita [Gate] de San Cosme just outside the city (Ulysses S. Grant placed small howitzers in church steeples overlooking the city). Worth’s troops were among the first to enter—and last to leave—Mexico City as the capital fell. (Map from Wikipedia.)

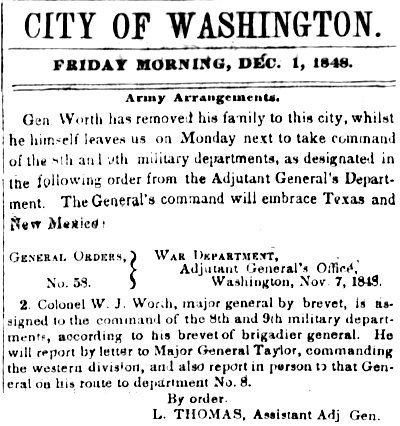

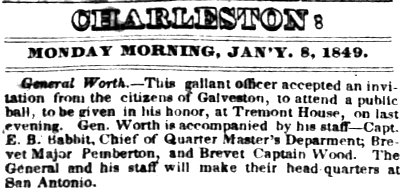

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in 1848, Worth was assigned to head the Army’s Department of Texas.

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in 1848, Worth was assigned to head the Army’s Department of Texas.

The department’s headquarters were in San Antonio.

The department’s headquarters were in San Antonio.

Among Worth’s goals in the vast new state was to establish a line of forts along the Anglo frontier from the Red River southwest to the Rio Grande. (One of those forts would be Fort Worth.)

He would not live to accomplish that goal.

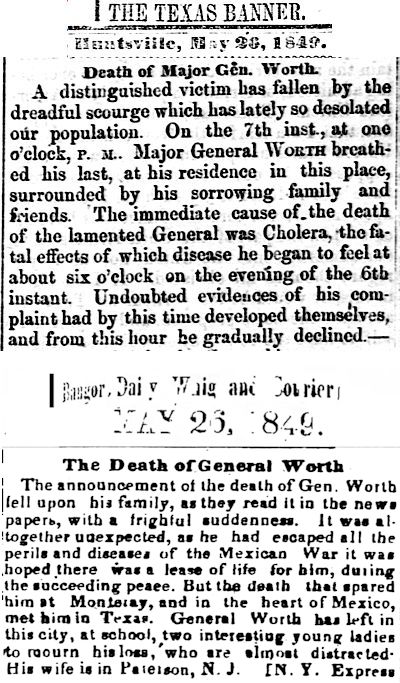

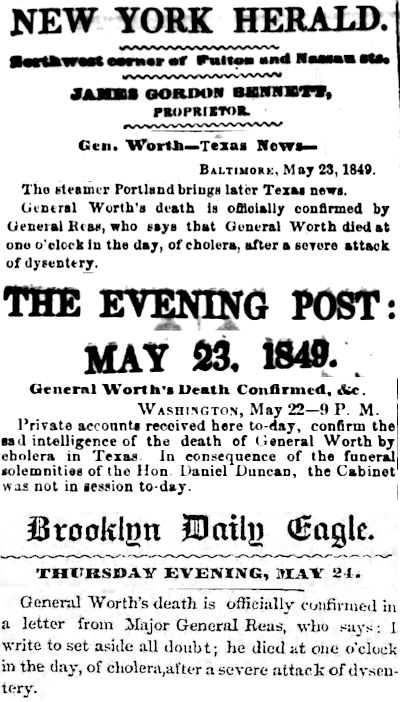

On May 6, 1849 Worth reported that he was feeling “indisposed” but continued in his duties nonetheless. He had been preparing a regiment to march six hundred miles to El Paso. But ten soldiers in the regiment had been buried the previous night after dying of cholera, and those deaths, his family later said, weighed on his mind.

Later that day the general himself began to show symptoms. He died before sunrise the next day.

He was buried in San Antonio.

The death of General Worth was reported across the country from Texas to Maine (Texas was the westernmost of the thirty states).

The death of General Worth was reported across the country from Texas to Maine (Texas was the westernmost of the thirty states).

But Worth’s death was reported most heavily in his native New York State.

But Worth’s death was reported most heavily in his native New York State.

A month after Worth died, Ripley Allen Arnold, now a major, who had fought under Worth in Florida and Mexico, established the Army’s fort at the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the Trinity River and named the fort in honor of his late commander.

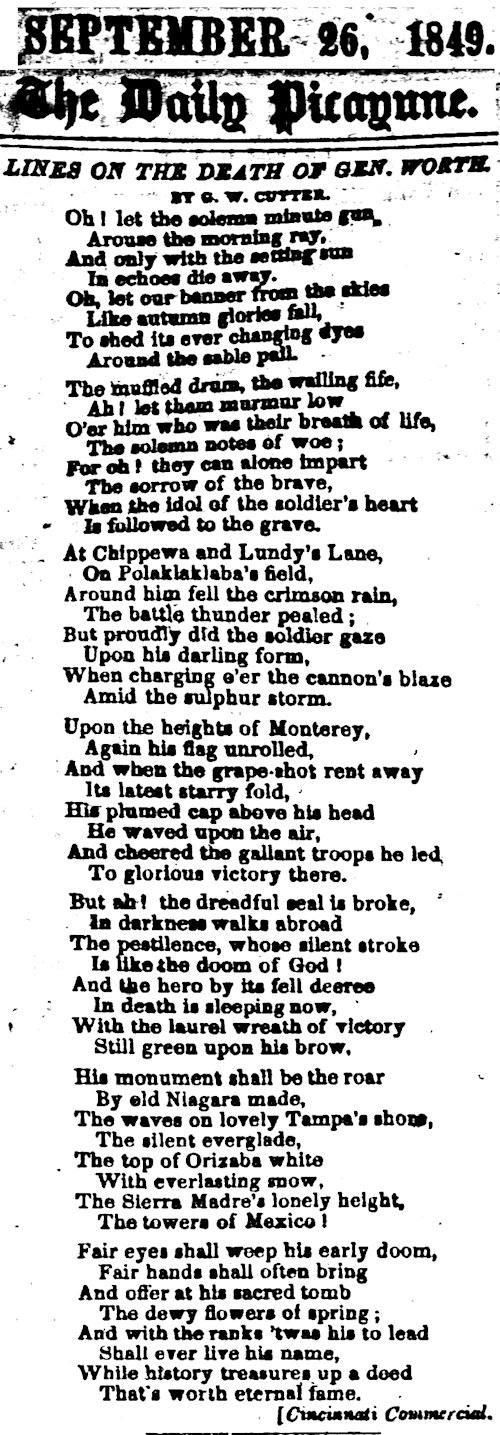

This poem memorializing Worth mentions the sites of some of his battles in Canada, Florida, and Mexico.

This poem memorializing Worth mentions the sites of some of his battles in Canada, Florida, and Mexico.

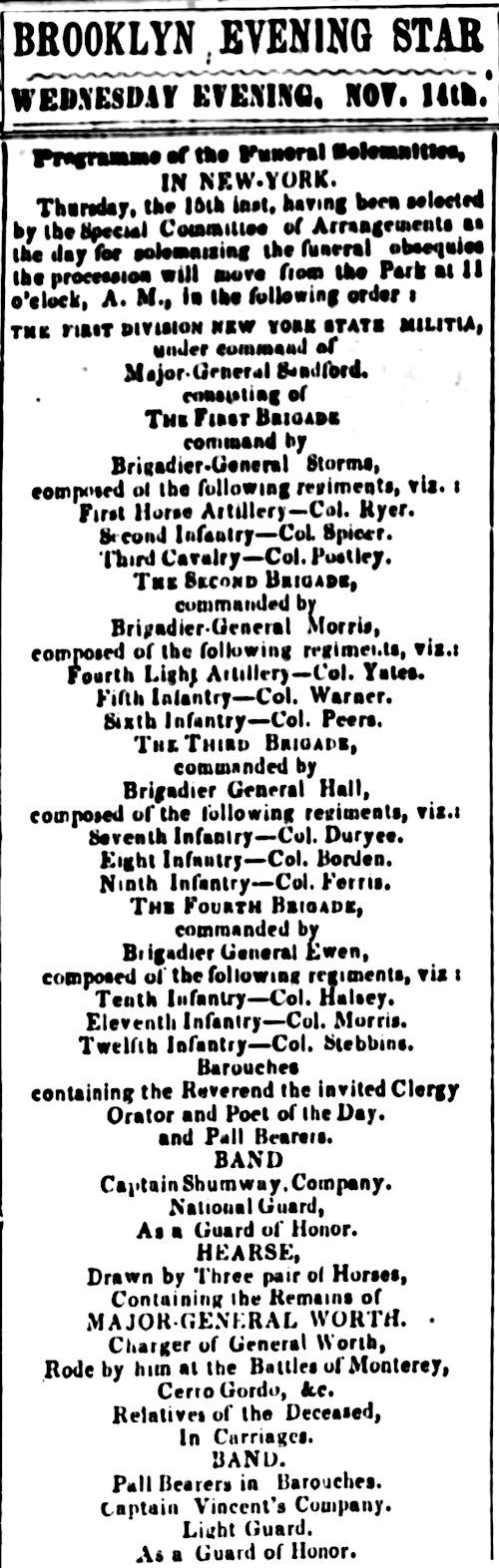

In November 1849 Worth was reburied in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn. Taking part in the funeral procession was the “charger” he had ridden in battle in Mexico.

In November 1849 Worth was reburied in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn. Taking part in the funeral procession was the “charger” he had ridden in battle in Mexico.

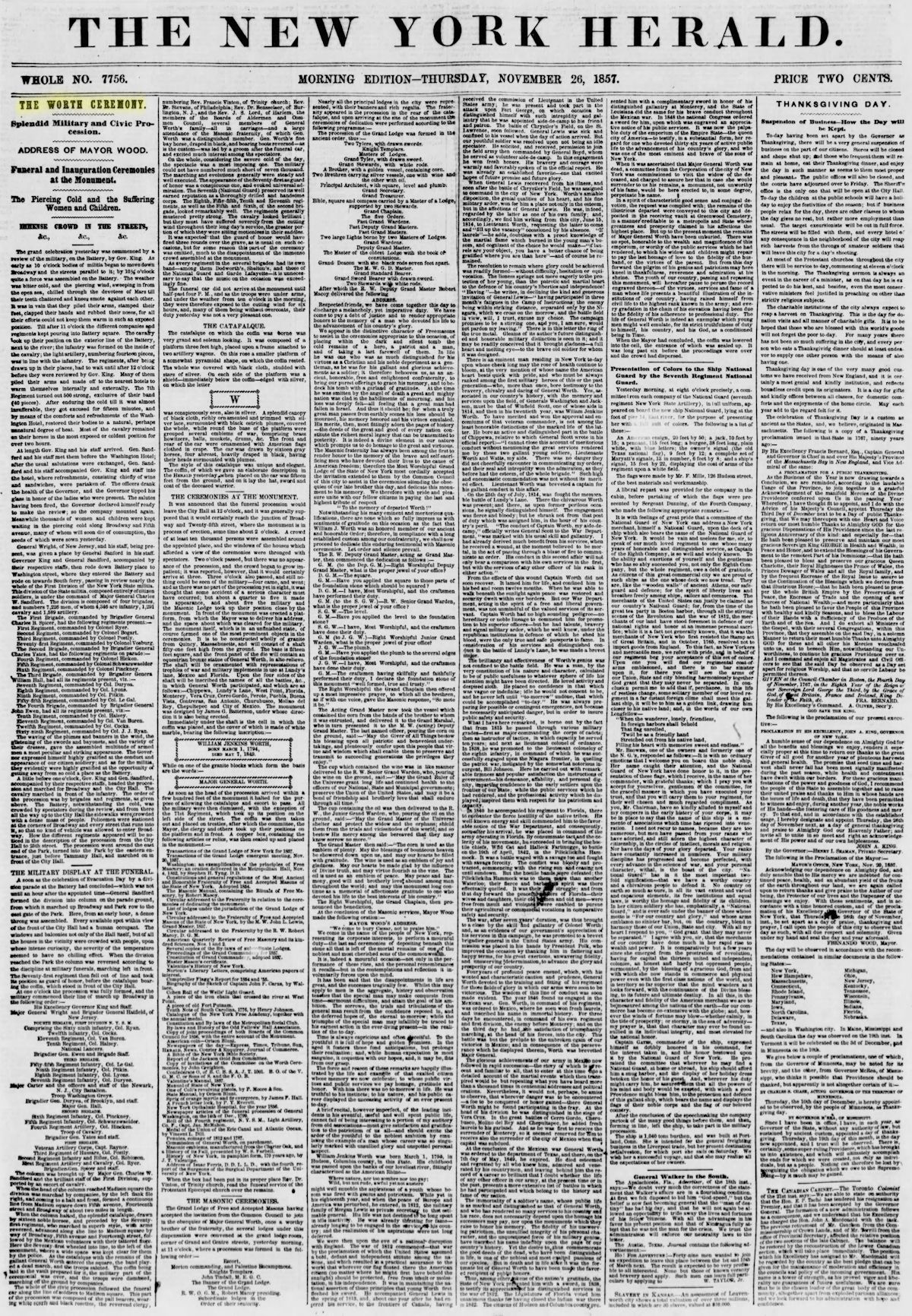

Fast-forward eight years. On November 25, 1857 General Worth was reburied in tiny Worth Square at the intersection of Broadway and 5th streets in Manhattan. More than six thousand soldiers took part in the ceremony. The New York Herald devoted more than four columns of its front page to the reburial.

Fast-forward eight years. On November 25, 1857 General Worth was reburied in tiny Worth Square at the intersection of Broadway and 5th streets in Manhattan. More than six thousand soldiers took part in the ceremony. The New York Herald devoted more than four columns of its front page to the reburial.

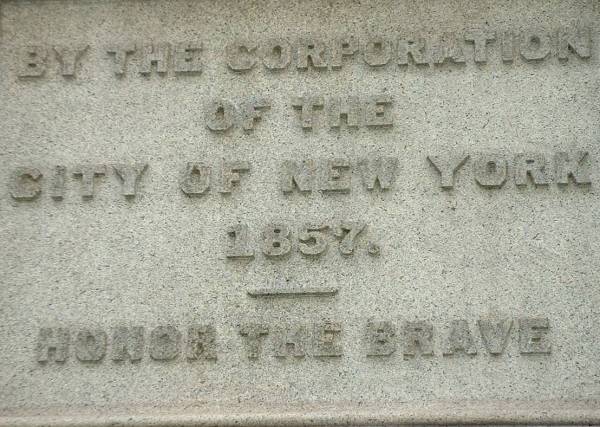

The centerpiece of Worth Square is a fifty-one-foot-tall granite monument. Bands around the obelisk are inscribed with the names of places significant in Worth’s career: Chippawa, West Point, Florida, Monterrey, Vera Cruz, Churubusco, Contreras, Molino Del Rey, City of Mexico, San Antonio.

The centerpiece of Worth Square is a fifty-one-foot-tall granite monument. Bands around the obelisk are inscribed with the names of places significant in Worth’s career: Chippawa, West Point, Florida, Monterrey, Vera Cruz, Churubusco, Contreras, Molino Del Rey, City of Mexico, San Antonio.

A bronze bas-relief depicts Worth wearing a plumed helmet as he sits with sword drawn astride his charger .

A bronze bas-relief depicts Worth wearing a plumed helmet as he sits with sword drawn astride his charger .

The square is enclosed by a cast-iron fence whose pickets are replicas of Worth’s Congressional Sword of Honor, awarded for his service at the Battle of Chapultepec. Each picket is topped by a plumed helmet, mimicking the helmet Worth wears in the bas-relief.

The Worth Monument is the second oldest monument in New York City. The oldest is the 1856 George Washington monument at Union Square. The Worth Monument also is one of only two New York City monuments that also serves as a mausoleum. The other is Grant’s Tomb.

Now hold your horses a New York minute: If ever on a quiz show you are asked what Cowtown and Manhattan have in common, before you answer with, “Not a dadburned thang, no siree Bob,” consider this:

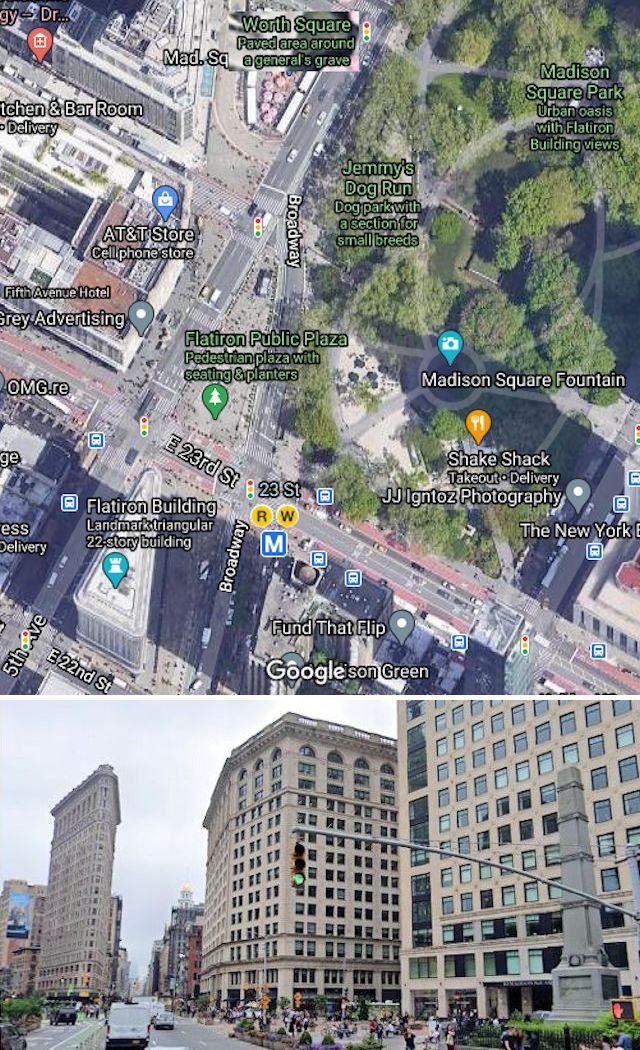

Manhattan’s Worth Square, commemorating New York State’s native son, is located one block from Manhattan’s Flatiron Building.

Manhattan’s Worth Square, commemorating New York State’s native son, is located one block from Manhattan’s Flatiron Building.

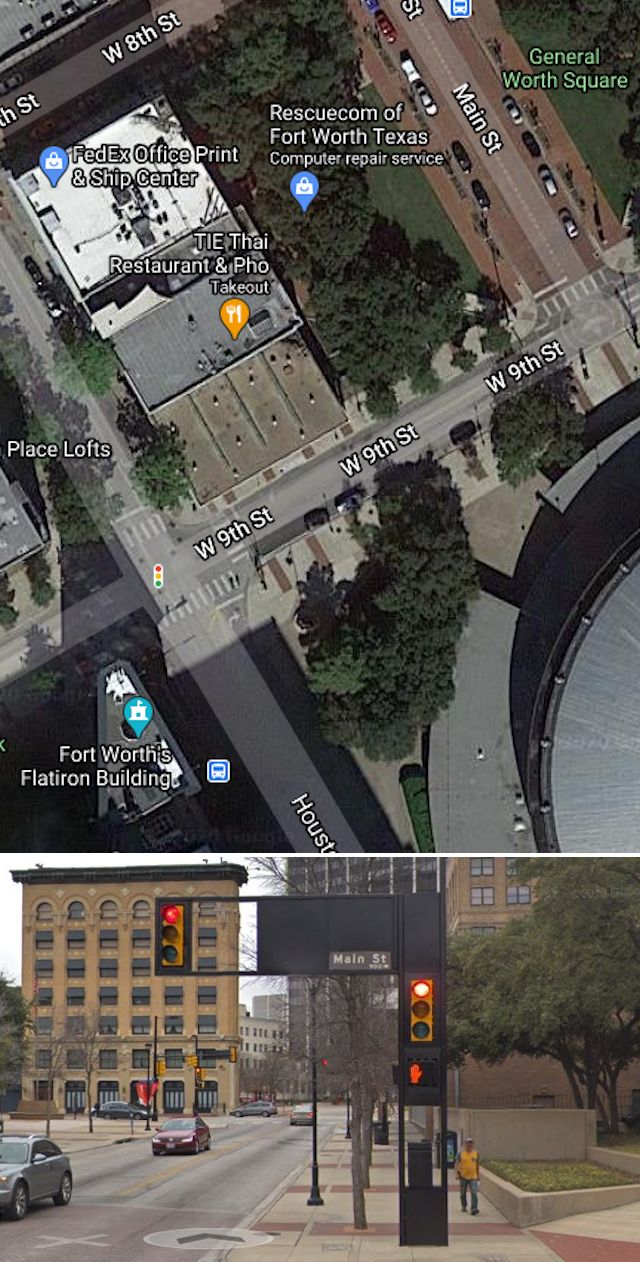

Fort Worth’s Worth Square, commemorating the city’s namesake, is located one block from Fort Worth’s Flatiron Building.

Fort Worth’s Worth Square, commemorating the city’s namesake, is located one block from Fort Worth’s Flatiron Building.