Just west of the Lockheed Martin “bomber plant” aptly named Shore View Drive meanders through a wooded peninsula sandwiched between the Northwest Loop and the coves of Lake Worth. Names of the peninsula’s streets reflect its waterside setting: Heron Drive, Killdeer Circle, Sandpiper Circle, Mallard Court.

Today the peninsula is sparsely developed with upscale houses, but thirty-eight years ago houses were even fewer and smaller, many of them wood-framed cottages.

Today the peninsula is sparsely developed with upscale houses, but thirty-eight years ago houses were even fewer and smaller, many of them wood-framed cottages.

In 1982 residents of the peninsula felt safe. They took walks at night. They rode their bicycles on their streets, some of which were unpaved. Some residents slept with their doors unlocked. Residents’ biggest concern about crime was illegal dumping in their isolated neighborhood.

Then, about 6:25 a.m. on August 10 Mrs. Junett Bryant telephoned her son, Ricky Lee Bryant, to be sure he was awake to go to work at nearby General Dynamics. Ricky Bryant lived at 8344 Shore View Drive (see satellite photo). Ricky Bryant, thirty-one, was a graduate of Arlington Heights High School and had lived around the lake most of his life.

Ricky Bryant also was Democratic chairman of precinct 113. Mother and son planned to attend a meeting that evening to become familiar with new voting machines. Mrs. Bryant, who lived on the lake two miles from Ricky, told him she would pick him up about 4:30 p.m.

At 4:38 a Fort Worth police department telephone operator received a call:

“I need somebody out here right now,” a woman’s voice said. “My son’s been murdered.”

“How do you know he’s been murdered?” the operator asked.

“Well, he doesn’t have a head.”

Two patrolmen were dispatched to 8344 Shore View Drive. They found the body of Ricky Lee Bryant on the floor of his bedroom, his severed head in the crook of his arm.

He also had been castrated.

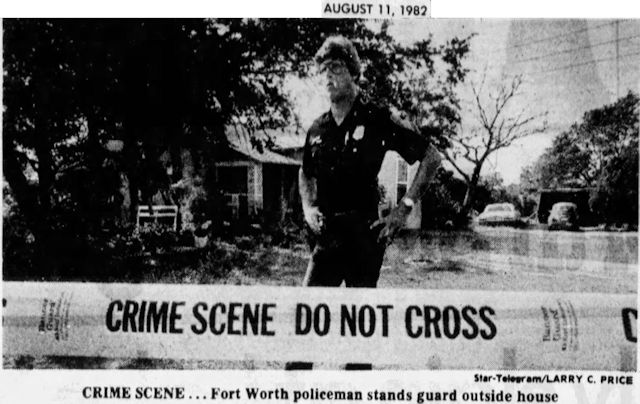

The patrolmen notified headquarters, which dispatched a homicide detective and a Tarrant County medical examiner to the scene.

But the nightmare on Shore View Drive was just beginning.

After notifying police headquarters the two patrolmen walked next door to 8340 Shore View Drive, a cottage about one hundred feet from the Bryant cottage.

After notifying police headquarters the two patrolmen walked next door to 8340 Shore View Drive, a cottage about one hundred feet from the Bryant cottage.

The patrolmen knocked on the front door, received no reply, and looked through a window.

Two bodies were lying on a floor.

Entering the cottage through an unlocked back door, the patrolmen found four people dead:

Ms. Georgia Ann Reed, thirty-four; her son, Scott Willard Reed, eleven; her mother, Earline H. Barker, fifty-five; and Bruce Gardner, thirty-three.

All four had been shot and stabbed. The throats of three of the four victims had been slit.

Police found .22-caliber shell casings in both cottages.

The medical examiner later determined that all five victims had been killed within a span of a few minutes between 6:25 a.m. and noon.

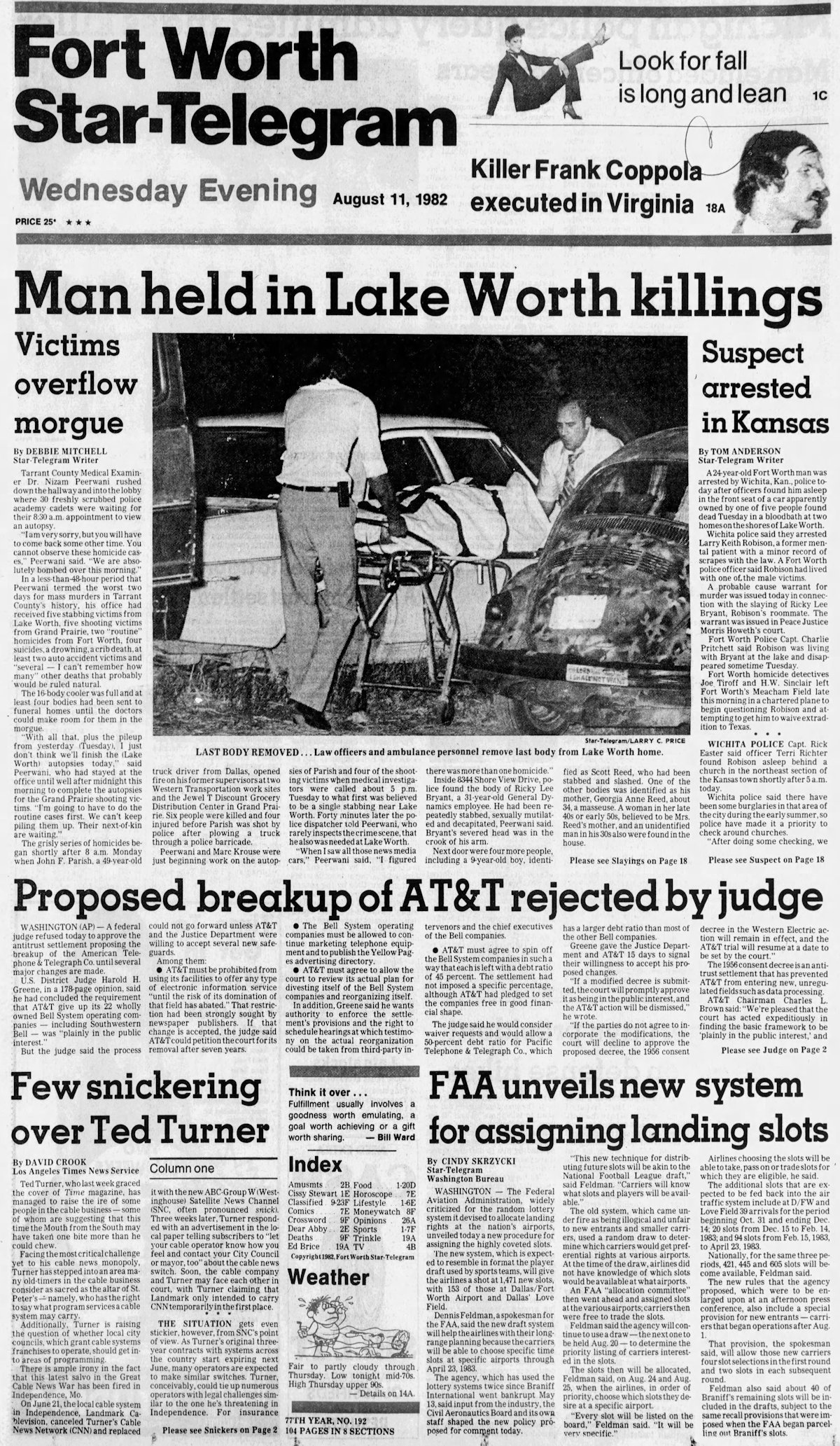

Police learned that two weeks earlier Ricky Bryant had taken a housemate, Larry Keith Robison, twenty-four, who was out of work. Robison and Bryant had known each other about eight months. Interviewing neighbors, police learned that Robison had not been seen since the murders were discovered.

Robison was arrested about 4:15 a.m. August 11 in Wichita, Kansas after police there found him sleeping in the back of a car parked at a church about two blocks from Interstate 35.

Robison was arrested about 4:15 a.m. August 11 in Wichita, Kansas after police there found him sleeping in the back of a car parked at a church about two blocks from Interstate 35.

Robison told Wichita police he was sleeping in the car because “he was going to Chicago and needed a place to rest.”

In the car police found wallets belonging to victims Bryant and Gardner.

Police also found a .22-caliber revolver in the car and arrested Robison for unlawful possession of a firearm.

He did not resist arrest.

Wichita police soon learned that the car was registered to Gardner and that Robison was wanted for questioning in the Fort Worth murders.

In Fort Worth a probable cause arrest warrant for murder was issued for Robison.

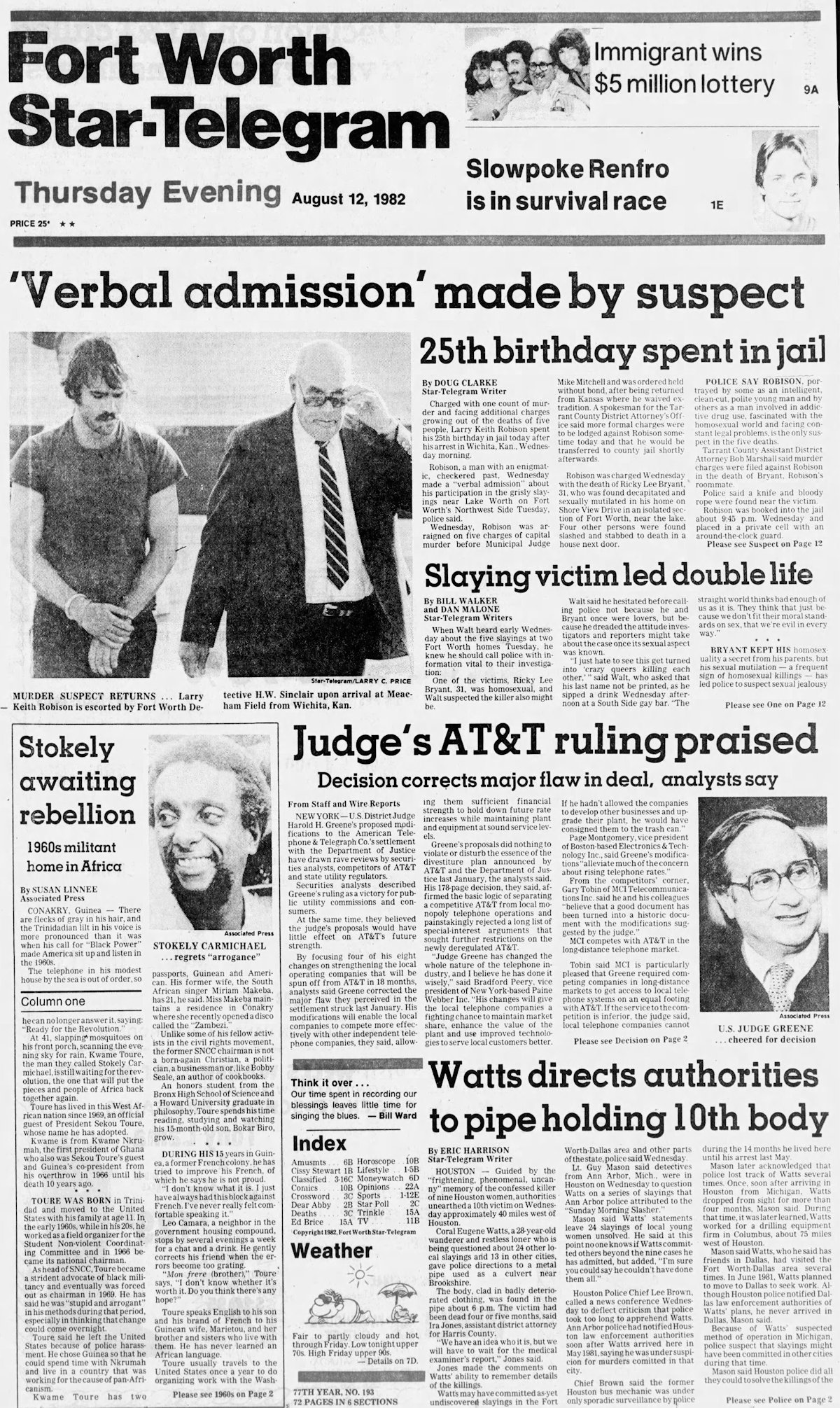

Fort Worth police returned Robison to Fort Worth in a chartered airplane.

Robison gave police a “verbal admission” of guilt and was arraigned on five charges of capital murder. He spent his twenty-fifth birthday in a private jail cell. A guard stood outside around the clock.

Robison gave police a “verbal admission” of guilt and was arraigned on five charges of capital murder. He spent his twenty-fifth birthday in a private jail cell. A guard stood outside around the clock.

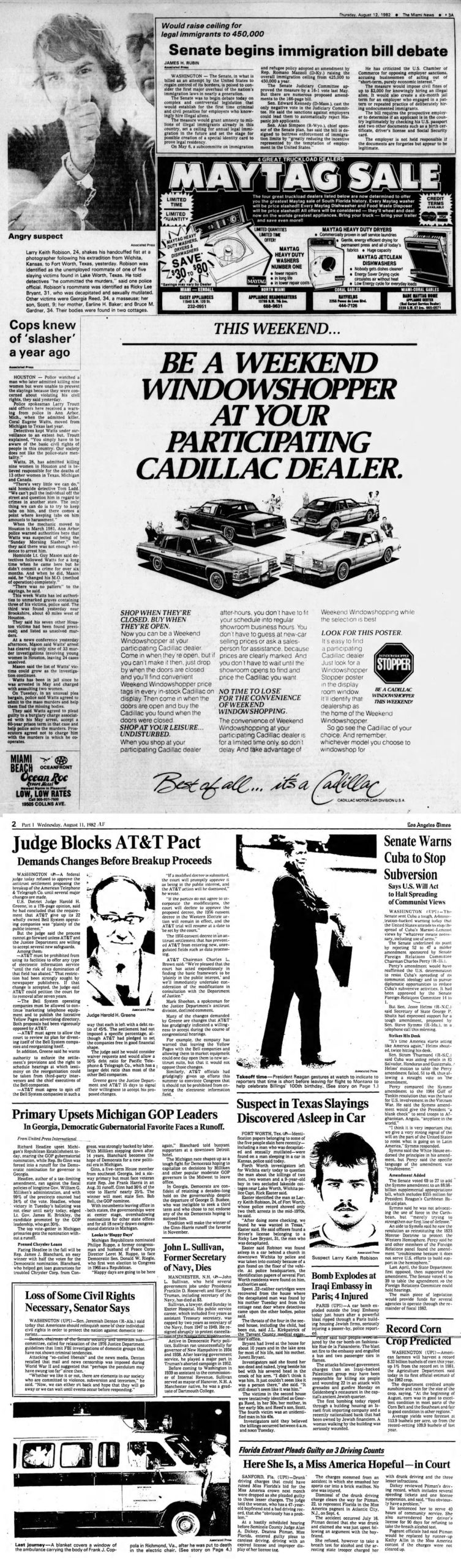

The story was news from Miami (top photo) to Los Angeles (bottom photo). The Miami photo shows Robison smiling and pretending to fire bullets from his index finger at photographers as he was being led from the airplane to a waiting police car. The Star-Telegram reported that scrapes were noticeable on Robison’s chin and arms.

The story was news from Miami (top photo) to Los Angeles (bottom photo). The Miami photo shows Robison smiling and pretending to fire bullets from his index finger at photographers as he was being led from the airplane to a waiting police car. The Star-Telegram reported that scrapes were noticeable on Robison’s chin and arms.

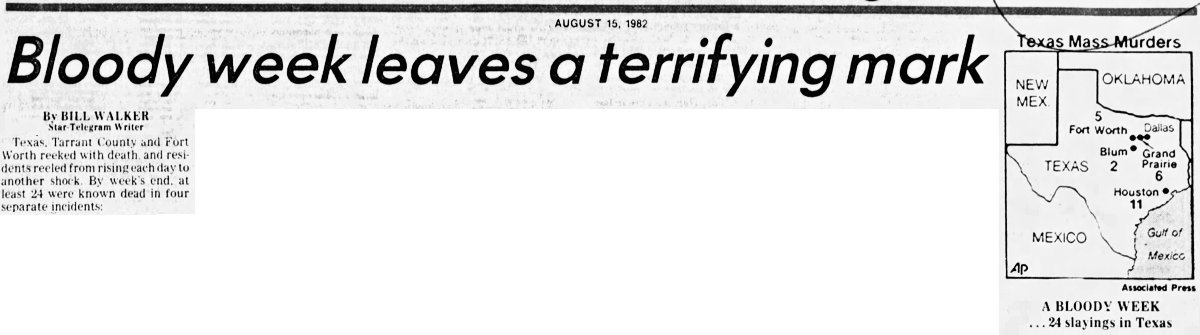

As horrific as the massacre on Shore View Drive was, numerically it was not the worst of crimes in Texas during a week in which twenty-four people were murdered or their murders were revealed. On the day before Larry Keith Robison’s rampage, in Grand Prairie disgruntled truck driver John F. Parish shot to death six people at two former places of employment before he in turn was shot to death by police as he drove through a police barricade. In Houston mechanic Coral Eugene Watts led police to the shallow graves of three women. He told police he had killed a total of twenty-two women in Texas, Michigan, and Canada.

As horrific as the massacre on Shore View Drive was, numerically it was not the worst of crimes in Texas during a week in which twenty-four people were murdered or their murders were revealed. On the day before Larry Keith Robison’s rampage, in Grand Prairie disgruntled truck driver John F. Parish shot to death six people at two former places of employment before he in turn was shot to death by police as he drove through a police barricade. In Houston mechanic Coral Eugene Watts led police to the shallow graves of three women. He told police he had killed a total of twenty-two women in Texas, Michigan, and Canada.

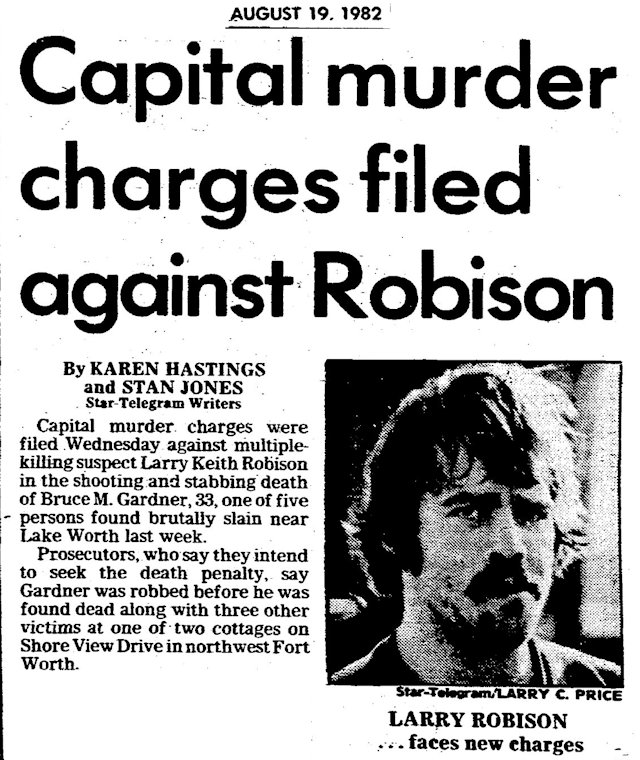

Prosecutors charged Larry Keith Robison with the capital murder of one of the five Shore View Drive victims: Bruce Gardner. Prosecutors chose Gardner because they planned to argue in court that by taking Gardner’s car, wallet, rings, and watch Robison murdered Gardner during the commission of a robbery—a crime that allows a charge of capital murder, which carries a penalty of life imprisonment or death.

Prosecutors charged Larry Keith Robison with the capital murder of one of the five Shore View Drive victims: Bruce Gardner. Prosecutors chose Gardner because they planned to argue in court that by taking Gardner’s car, wallet, rings, and watch Robison murdered Gardner during the commission of a robbery—a crime that allows a charge of capital murder, which carries a penalty of life imprisonment or death.

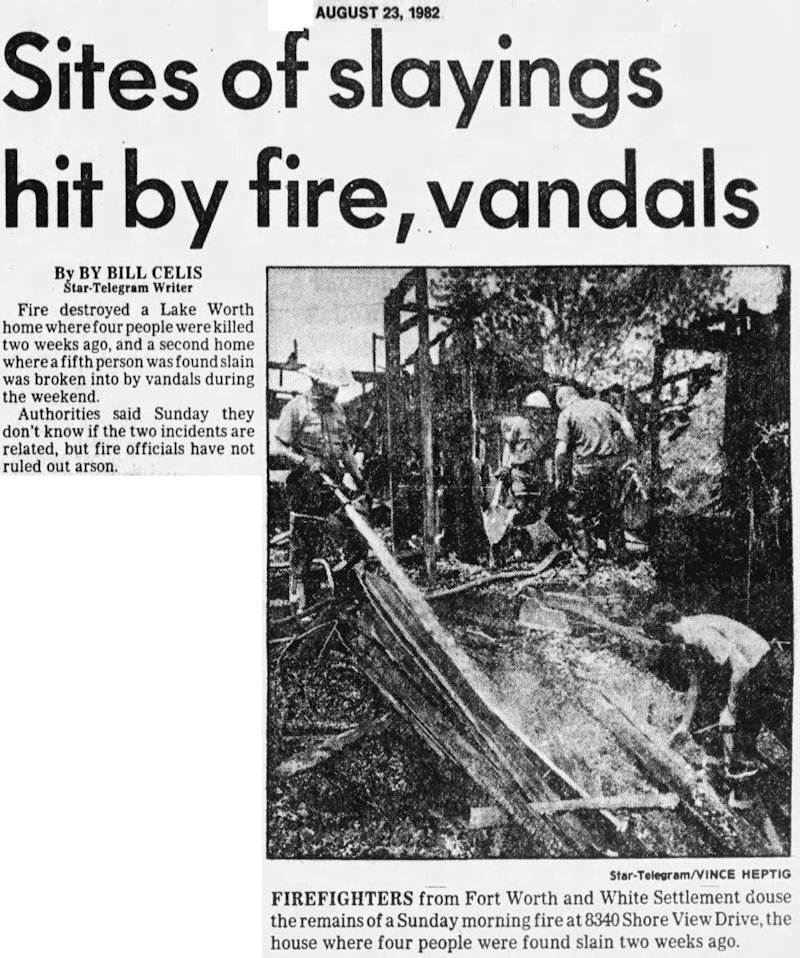

A few days after the murders, the Reed cottage was destroyed by fire, and the Bryant cottage was broken into by vandals.

A few days after the murders, the Reed cottage was destroyed by fire, and the Bryant cottage was broken into by vandals.

After interviewing friends, family, and colleagues of the suspect and victims, investigators theorized that victims Ricky Lee Bryant and Georgia Ann Reed had more in common than being next-door neighbors: Each was Larry Keith Robison’s lover.

But the nightmare on Shore View Drive was born of a murkier motive than romance.

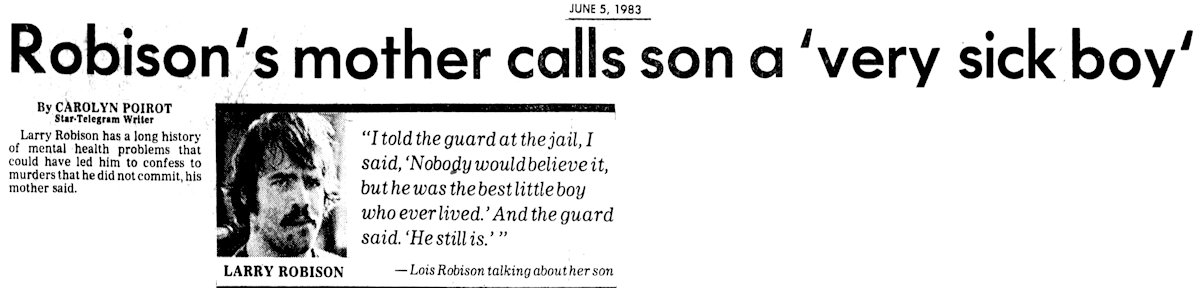

In an interview with the Star-Telegram, Robison’s mother characterized him as “the sweetest little boy that ever lived” who became “a very sick boy” and ultimately was failed by the mental-health system.

In an interview with the Star-Telegram, Robison’s mother characterized him as “the sweetest little boy that ever lived” who became “a very sick boy” and ultimately was failed by the mental-health system.

“Larry was . . . good-natured and quiet, a bookworm, involved in Scouts and Little League. . . . He won honors in Scouts and almost made [the rank of] Eagle. He was a darling boy, the kind of kid every mother would be proud of,” Mrs. Robison said.

“He was always such a good student and never got into any trouble until he was about twelve and began having problems at school. He started doing foolish things that didn’t make much sense . . . He would do things and tell me that voices told him to do them.

“He begged me to help him, and I tried. I talked to doctors, psychologists, chaplains, and judges and couldn’t get any help. He was finally diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenic four years ago when he was twenty-one.”

She said her son often threatened to kill himself and walked out of three psychiatric facilities because, he said, voices told him to leave. She said he had attempted suicide twice in the last year despite being locked in solitary confinement in a “safety cell.”

“A judge told me once unless he commits a violent crime, you can’t get him committed,” she said. “He was in jail in Weatherford once, and I begged them to keep him or get him committed, and they said they couldn’t.

“Peter Smith [Hospital] and the [Veterans Administration] hospital in Waco said they couldn’t keep him because they needed the beds. All I know is, if we had been able to get him help, he wouldn’t be where he is now.”

On October 9 Robison tried to kill himself again. He slit his wrist with a razor in his cell in county jail and was hospitalized. Sheriff Lon Evans said Robison had been placed in an isolation cell under constant monitoring but was moved to a cell in the general jail population on the advice of a doctor.

On October 9 Robison tried to kill himself again. He slit his wrist with a razor in his cell in county jail and was hospitalized. Sheriff Lon Evans said Robison had been placed in an isolation cell under constant monitoring but was moved to a cell in the general jail population on the advice of a doctor.

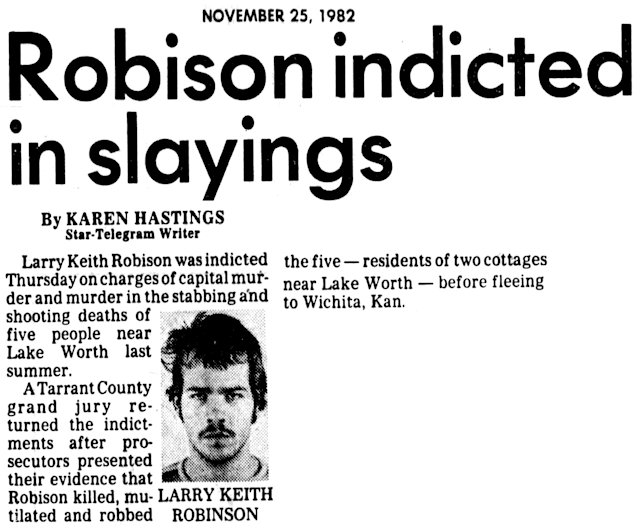

Robison was indicted on charges of murder and capital murder. Of the capital murder indictment, Assistant District Attorney Larry Moore said, “With each of the victims, except the young boy, Robison stole property from them. Our position is that what happened here is that these were robbery-murders. Although his primary intention was to murder these people, he did in fact rob them.”

Robison was indicted on charges of murder and capital murder. Of the capital murder indictment, Assistant District Attorney Larry Moore said, “With each of the victims, except the young boy, Robison stole property from them. Our position is that what happened here is that these were robbery-murders. Although his primary intention was to murder these people, he did in fact rob them.”

Robison never denied that he killed five people on Shore View Drive. But his family and court-appointed attorneys maintained that he was suffering paranoid-schizophrenic delusions at the time.

Robison never denied that he killed five people on Shore View Drive. But his family and court-appointed attorneys maintained that he was suffering paranoid-schizophrenic delusions at the time.

In May 1983 Robison’s attorneys said he would plead not guilty by reason of insanity, citing his drug use and history of admission to psychiatric facilities.

But on June 9 the Star-Telegram reported that Dallas psychiatrist Dr. E. Clay Griffith had interviewed Robison for the court and concluded that Robison was sane enough to stand trial. Griffith reported that Robison showed “no unusual behavior” and showed emotional reactions “well within normal limits.”

Griffith said the one exception was when Robison used a paper hand puppet to answer some of Griffith’s questions.

The Star-Telegram did not elaborate.

Robison’s trial began with testimony by Ricky Bryant’s mother and the responding police officers, who described what they saw at the two cottages on Shore View Drive on August 10, 1982.

Robison’s trial began with testimony by Ricky Bryant’s mother and the responding police officers, who described what they saw at the two cottages on Shore View Drive on August 10, 1982.

Judy Smith, a friend of Robison, testified for the prosecution about a telephone call that Robison made to her from jail. She said Robison told her that he had felt compelled to kill his “evil” housemate and the four people in the Reed cottage.

Judy Smith, a friend of Robison, testified for the prosecution about a telephone call that Robison made to her from jail. She said Robison told her that he had felt compelled to kill his “evil” housemate and the four people in the Reed cottage.

“He said part of him knew it was wrong, and part of him said to do it,” Smith said. “He said the side that wanted to do it won out.”

Smith testified that Robison said, “You’re going to think I’m crazy, but I felt like it was God wanting me to do it.”

Robison also described “pressure” in his head, Smith said.

Smith said that Robison thought Ricky Lee Bryant and Georgia Reed were evil because Bryant “read the Tarot” fortune-telling cards, and Georgia Reed was “into witchcraft.”

Smith said Robison also felt that Bryant was trying to control him.

When Smith asked Robison why he killed “that little boy” (Scott Willard Reed, eleven), Robison answered that he “didn’t want any witnesses.”

Smith said Robison told her he killed Bryant first. After Robison could not find the keys to Bryant’s car to flee the crime scene, Robison went next door to steal a car. Smith said Robison told her that he killed the four occupants of the Reed cottage and fled in Bruce Gardner’s car.

Prosecutors said Gardner had been in the wrong place at the wrong time: Gardner had arrived at the Reed cottage to pick up Georgia Reed for a date just as Robison was killing Reed, her mother, and son.

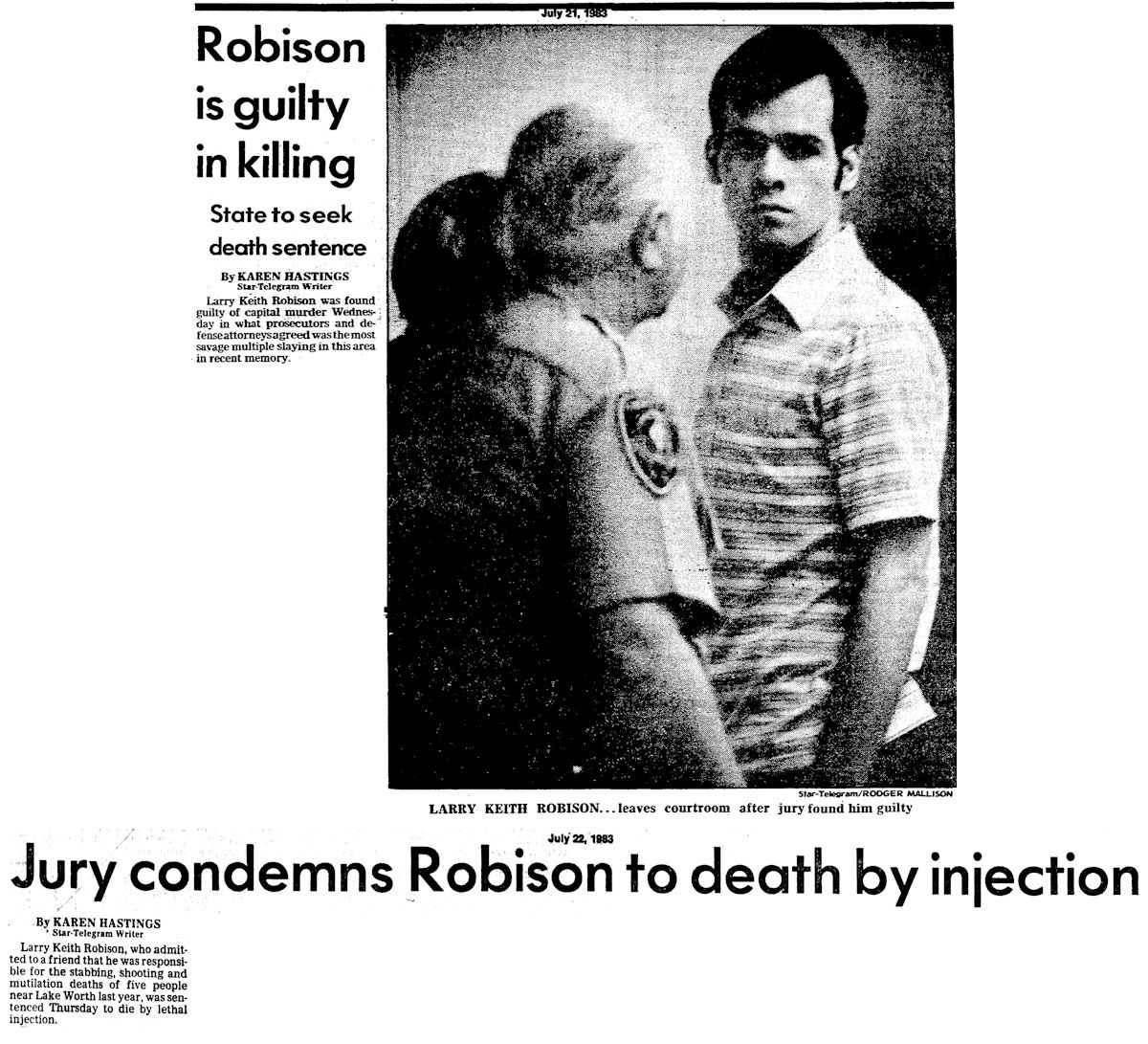

The jury found Larry Keith Robison guilty of capital murder and sentenced him to death at the prison in Huntsville.

The jury found Larry Keith Robison guilty of capital murder and sentenced him to death at the prison in Huntsville.

To assess the death penalty, a jury must conclude that murder was committed deliberately and that there is a probability that the defendant will continue to pose a threat to society.

One Robison juror said, “That was the question that posed the most problem to the jurors. It does somewhat make you a seer. None of us can do that. We all had to be sure in our own minds that we felt that there was a probability.”

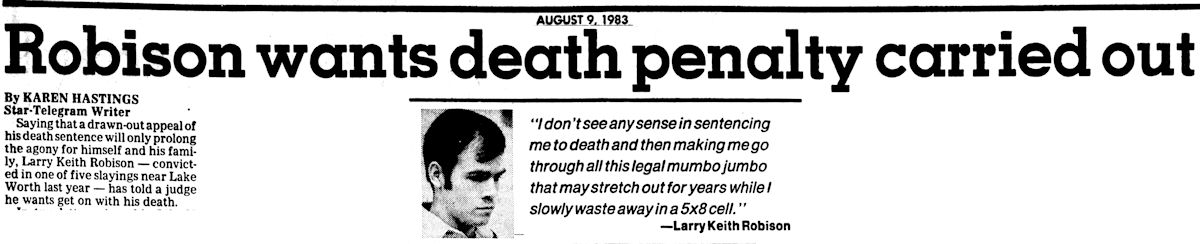

As Robison’s attorneys prepared to appeal the conviction, Robison told his trial judge that he did not want a retrial. Robison said, “All I want to do is get out of this cell and go on down to Huntsville and take my punishment like a man. . . . I have been here a year, I am not healthy. All you can do is prolong my agony.”

As Robison’s attorneys prepared to appeal the conviction, Robison told his trial judge that he did not want a retrial. Robison said, “All I want to do is get out of this cell and go on down to Huntsville and take my punishment like a man. . . . I have been here a year, I am not healthy. All you can do is prolong my agony.”

The judge reminded Robison that an appeal is mandatory after conviction for capital crimes.

In 1984 Robison’s parents formed HOPE (Help Our Prisoners Exist), an organization whose goal was to abolish capital punishment, which the Robisons called arbitrary and inherently unfair.

In 1984 Robison’s parents formed HOPE (Help Our Prisoners Exist), an organization whose goal was to abolish capital punishment, which the Robisons called arbitrary and inherently unfair.

In March 1985 ten Texas death row inmates, including Larry Keith Robison, filed motions to have all their appeals dropped and called for quick executions so the ten inmates could “stop lining the pockets of attorneys and judges,” the leader of the effort said.

In March 1985 ten Texas death row inmates, including Larry Keith Robison, filed motions to have all their appeals dropped and called for quick executions so the ten inmates could “stop lining the pockets of attorneys and judges,” the leader of the effort said.

James E. Smith, convicted of a robbery-murder in Houston, said, “To continue to wait here year after year, with the psychological and physical stress, it’s inhuman at least. We will no longer participate in this obscene exercise.”

In April 1986 Robison was granted a retrial after an appeals court ruled that his attorneys had been denied a full opportunity to challenge a juror who was prejudiced against Robison’s defense of insanity.

In April 1986 Robison was granted a retrial after an appeals court ruled that his attorneys had been denied a full opportunity to challenge a juror who was prejudiced against Robison’s defense of insanity.

In 1987 Robison granted his first interview since his 1982 trial. He told the Star-Telegram that he was insane at the time of the five murders—“on an aborted mission of mercy to free the souls of everyone on Earth so they and he could unite with God.”

In 1987 Robison granted his first interview since his 1982 trial. He told the Star-Telegram that he was insane at the time of the five murders—“on an aborted mission of mercy to free the souls of everyone on Earth so they and he could unite with God.”

“At one time a frequent abuser of LSD and other drugs,” the Star-Telegram wrote, “Robison insists he was in the grip of powerful delusions when he killed—wrapped up in a perverted interpretation of the Bible and his own misdirected yearning for God.

Robison told the newspaper: “A lot of people claim, well, God told me to kill these people. It wasn’t like that. As a matter of fact it was like a struggle within myself from all the conditioning I’d had—you’re not supposed to kill people. But yet this other voice was saying a body is not important, just the soul.”

Robison said his mental illness began when he was abusing illegal drugs. At a party in 1978, he said, he felt himself soaring over Camp Bowie Boulevard, lighted like a neon sign and causing cars below to explode.

The newspaper wrote: “Always intrigued by the occult and mental telepathy, Robison said his life at one point became a ritual. He slept under a plywood pyramid, kept candles burning at all hours, and always had an open Bible in the room.

“By 1982 and for nearly a year after the killings, he said, he heard voices from what he calls ‘star people,’ saw secret code words in newspapers, and had trouble distinguishing reality from fantasy.”

Of the five murders Robison said, “I didn’t do this out of hate. I only did it because—it sounds crazy to say it—I wanted to find God.”

Robison said the idea for castrating Ricky Lee Bryant was inspired by a Bible passage about David presenting the foreskins of his enemies to Saul as battle trophies (1 Samuel 18:25-27).

For several hours, Robison said, he sat among the dead bodies on Shore View Drive, trying to work up the courage to kill himself.

Instead, Robison told the newspaper, he took the wallet, rings, and watch from Bruce Gardner’s corpse and fled in Gardner’s car so he could “trade identities” and be safe to kill again.

Later in 1987 at Robison’s retrial, defense attorney Sherry Hill repeated the contention that Robison suffered from paranoid schizophrenia.

Later in 1987 at Robison’s retrial, defense attorney Sherry Hill repeated the contention that Robison suffered from paranoid schizophrenia.

Robison was again sentenced to death.

“It seems to be God’s will. I accept it,” Robison said of the verdict.

After Robison’s second death sentence in 1987, appeals and other legal wrangling in his case dragged on for years.

But by 1999 Robison was scheduled to be executed. In an interview in July he said he was looking forward to his death like a child looking forward to Christmas, “waiting for Santa Claus to come.”

The next month Robison won a temporary reprieve less than five hours before his scheduled execution when the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals granted an appeal from his attorney, who argued that Robison should be examined to determine whether he was mentally competent to understand his fate.

Robison was ruled competent.

As the new execution date approached, the Vatican, Amnesty International, the European Union, and other organizations appealed to then-Governor George W. Bush to stay Robison’s execution.

Bush declined.

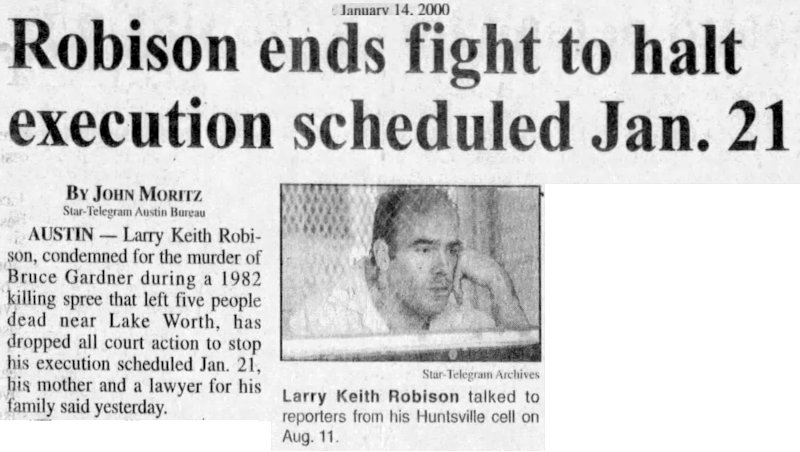

One week before his scheduled execution Robison ended his fight to halt the execution.

One week before his scheduled execution Robison ended his fight to halt the execution.

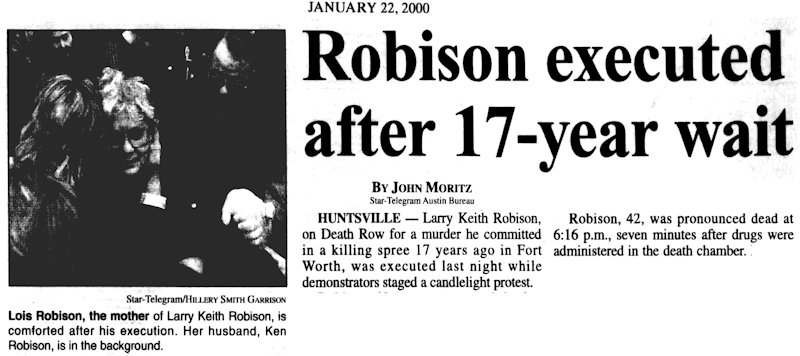

On January 21, 2000 Larry Keith Robison—“the sweetest little boy that ever lived” who became “a very sick boy”—was executed. He was then forty-two years old. Outside the prison in Huntsville protesters lit candles, carried signs, and sang hymns as they condemned the execution as inhumane.

On January 21, 2000 Larry Keith Robison—“the sweetest little boy that ever lived” who became “a very sick boy”—was executed. He was then forty-two years old. Outside the prison in Huntsville protesters lit candles, carried signs, and sang hymns as they condemned the execution as inhumane.

Six members of Robison’s family and six members of his victims’ families witnessed the execution in separate rooms.

Family members of Robison’s five victims said in a statement, “Justice has been done. Larry Robison has paid with his life for the seventeen-year nightmare of trauma and heartache he caused for the families of his victims.”

My best Friend, M.D. & myself were at the the Cottage to the right (if facing the homes) parked in the Drive waiting on our friend to arrive. This was on the weekend 10-days or so before the killings were discovered. It was a typical hot August day, & we were outside leaning against my 71 Mach I drinking Ice cold Coors in the can. here came this Maniac driver from north-northeast of us…Driving like a pure maniac. He wooped into the driveway at the cottage on our left, skidded to a crazy stop, got out of the car & headed our way at a brisk pace. My bud & I calmly looked at each other wondering “who in the hell is this clown”??? He was headed our way, shaking his arms & head real crazy like saying “Hey Bruce isn’t here man! Don’t ya’ll know his car isn’t here!” Bruce isn’t here!” We looked at the kook & told him “We know that”! We are just waiting on him” He mentioned our beers & told us he had a lot of cold beer next door. “Ya’ll come on over & have some” My bud & I didn’t even have to say a word or look at each other. We told him in Unison, “Nhaaa, wer’e good, we will just wait here on our friend. He turned around & headed back the same way he came over, mumbling & shaking his head. Wednesday morning, when the paper was thrown, my Bud call me around 7:00 am which was highly unusual & asked if I had got my paper yet, no, I said & he instructed me to go get while he held on the phone. There he was…The crazy MF we had run into 9 0r 10 days earlier. Then my Bud started crying a bit. I had no I idea why & asked, He said that Bruce Gardner ( Not the Bruce we were waiting on) was his best friend at Lockheed & had become pretty tight. Dammitman…Then I’m approached by Ricky Lee Green & Sharon Dollar near Casino Beach in April of 89??? They were creepy as hell too like Robison. If you have just a scant bit of instincts, you know when a person is just not quite right & you need to leave pronto…