During the era of segregation, the first two parks for African Americans in Fort Worth were Douglas Park and McGar Park (see Part 1). Both parks were privately owned, built on the near North Side by African-American entrepreneurs.

Douglas Park opened in 1895 in the river bottoms east of North Main Street. McGar Park was west of North Main Street just below the first Panther Park.

McGar Park opened about 1907 primarily to serve as the home park for the baseball teams owned by the park owner, Hiram McGar. McGar owned first McGar’s Wonders and later the Black Panthers.

But by 1910 McGar Park was offering “special seats for whites” and hosting white amateur baseball teams as well as African-American teams and thus lost its blacks-only status.

McGar Park closed in 1919. Eventually white squatters in the river bottoms dissuaded African Americans from using Douglas Park, which was being used by white amateur baseball leagues. The city realized that the African-American community needed more park space.

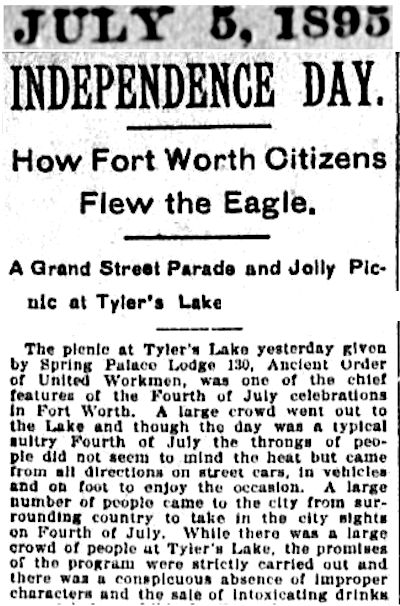

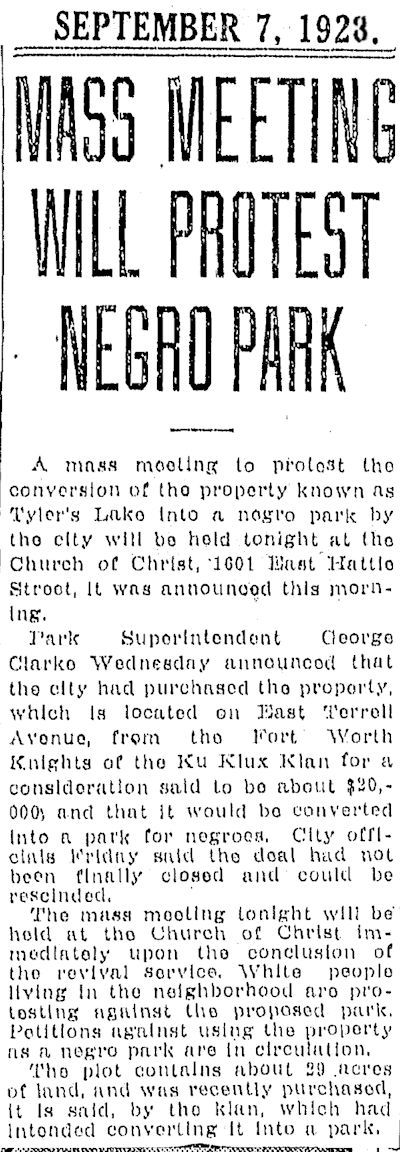

So, in 1923 parks superintendent George C. Clarke announced that the city of Fort Worth had bought Tyler’s Lake and its park in the Glenwood addition on the near East Side. Clarke announced that the city would dedicate the park for use by African Americans.

J. L. Tyler had developed the park in the 1880s, and it remained a popular resort into the new century. But in the early 1920s Tyler had sold his park to the Ku Klux Klan. In 1923 the city bought the lake and park from the Klan..

J. L. Tyler had developed the park in the 1880s, and it remained a popular resort into the new century. But in the early 1920s Tyler had sold his park to the Ku Klux Klan. In 1923 the city bought the lake and park from the Klan..

But white residents in Glenwood protested the city’s plan, and the city backed down.

Again Clarke did not give up.

By 1924 Clarke and the rest of the park board were considering restoring Douglas Park to its original purpose as a park for African Americans.

By 1924 Clarke and the rest of the park board were considering restoring Douglas Park to its original purpose as a park for African Americans.

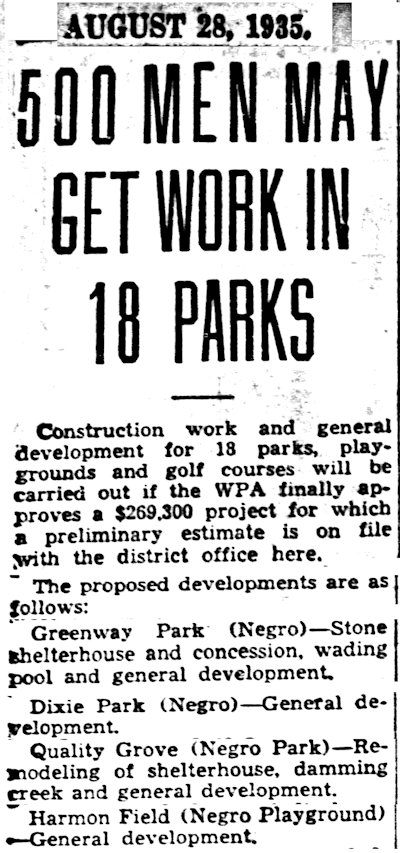

That restoration never came to be (see Part 1), but under Clarke’s superintendency in the 1920s the city developed three parks for African Americans: Harmon Field (1925), Dixie Park (1925), and Greenway Park (1928).

Harmon Field

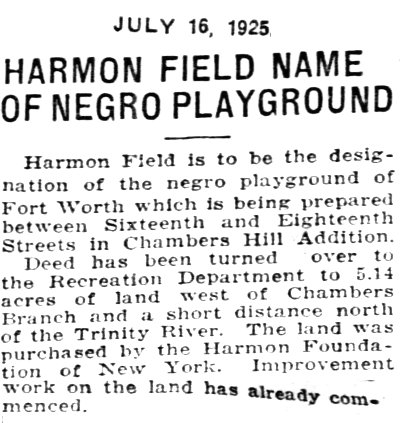

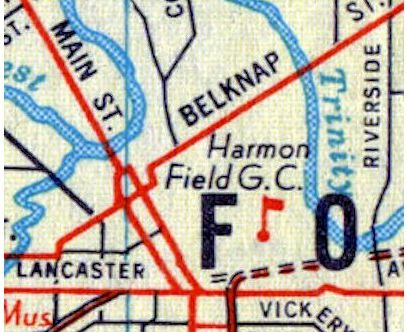

Harmon Field opened in 1925 on land donated by the Harmon Foundation of New York.

Harmon Field is located northeast of Terrell High School, west of the river, and north of Lancaster Avenue.

Harmon Field is located northeast of Terrell High School, west of the river, and north of Lancaster Avenue.

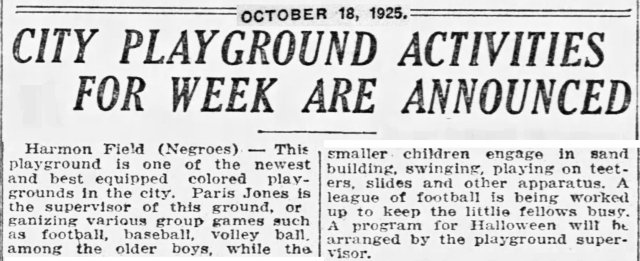

Early activities at the park included ball games for older boys and playground activities for younger children.

In the early 1950s, as African Americans continued their struggle for equality, they were not allowed access to the city’s municipal courses. In 1954, under pressure by the Fort Worth Negro Golf Association and other groups, the city built a nine-hole a golf course at Harmon Field. The city also built a recreation center.

In the early 1950s, as African Americans continued their struggle for equality, they were not allowed access to the city’s municipal courses. In 1954, under pressure by the Fort Worth Negro Golf Association and other groups, the city built a nine-hole a golf course at Harmon Field. The city also built a recreation center.

But by 1963 three highways—the turnpike, Interstate 35W, and U.S. 287—had nipped at the edges of Harmon Field, reducing its area. The city also sold fifteen acres of the park for industrial use. As African-American golfers increasingly played at previously whites-only courses, Harmon Field’s golf course was underused and closed in 1958.

Today Harmon Field retains its rec center and has six soccer fields.

Today Harmon Field retains its rec center and has six soccer fields.

Dixie Park

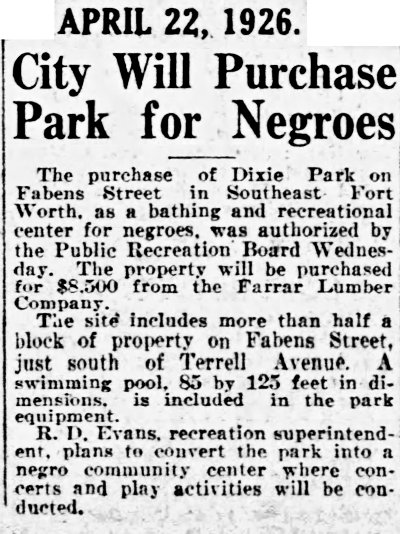

In 1926 the city bought little Dixie Park on East Rosedale Street at Fabons Street. Dixie Park had been a privately owned park for African Americans, and under city ownership the park continued to serve the African-American community.

In 1926 the city bought little Dixie Park on East Rosedale Street at Fabons Street. Dixie Park had been a privately owned park for African Americans, and under city ownership the park continued to serve the African-American community.

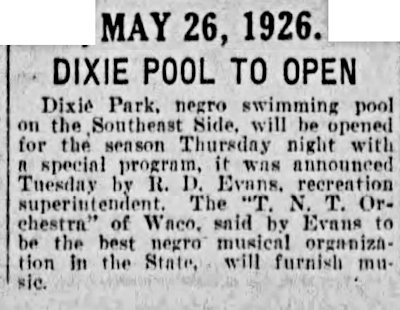

The centerpiece of Dixie Park was its swimming pool. The pool opened for the 1926 season as the T.N.T. Orchestra of Waco performed.

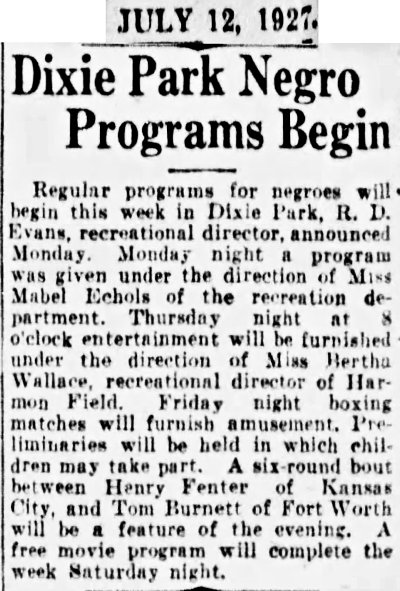

In 1927 boxing matches and a free movie were attractions at the park.

For a quarter-century the intersection of East Rosedale and Fabons streets was an entertainment crossroads for African Americans. In addition to the park, across Fabons Street was the Grand Theater (1938), one of the city’s few theaters for African Americans. In the photos the Grand Theater is the building on the left. In the 1952 aerial photo the park’s swimming pool is the white rectangle.

For a quarter-century the intersection of East Rosedale and Fabons streets was an entertainment crossroads for African Americans. In addition to the park, across Fabons Street was the Grand Theater (1938), one of the city’s few theaters for African Americans. In the photos the Grand Theater is the building on the left. In the 1952 aerial photo the park’s swimming pool is the white rectangle.

In 1951 the Star-Telegram listed Dixie Park among the locations where African Americans could celebrate Juneteenth. Note that the report says that for the first time African Americans would be allowed to play golf at Worth Hills course.

In 1951 the Star-Telegram listed Dixie Park among the locations where African Americans could celebrate Juneteenth. Note that the report says that for the first time African Americans would be allowed to play golf at Worth Hills course.

The Star-Telegram added: “Forest Park Zoo, the Botanic Gardens and the park concession rides, in the past open to Negroes only on ‘Juneteenth,’ are expected to attract large crowds. The city park department, in a change of policy, recently announced that ‘escorted groups’ of Negroes could visit the zoo and Botanic Gardens at all times.”

In 2002 Velvin Carter, then seventy, told the Star-Telegram: “Later on we got a park, they called it Dixie Park, that was a place that the blacks could go swim. That was the only place we could go swimming. We couldn’t hardly go to Forest Park. The only time we could go to Forest Park was on the 19th of June. They let us go swim at the Forest Park pool. For all the blacks, that was our day. Then the next day they would drain the pool. That’s what they did. You can put that in your paper.”

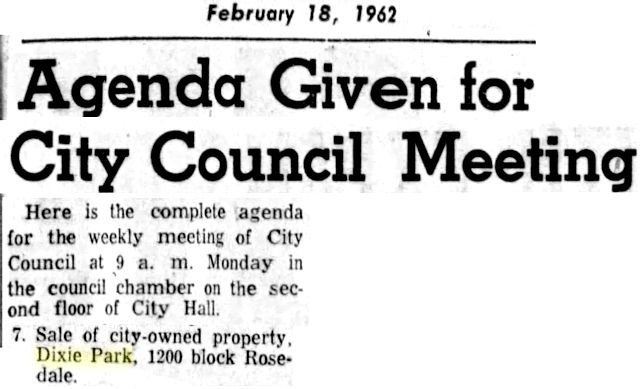

The city sold Dixie Park in 1962.

The city sold Dixie Park in 1962.

Greenway Park

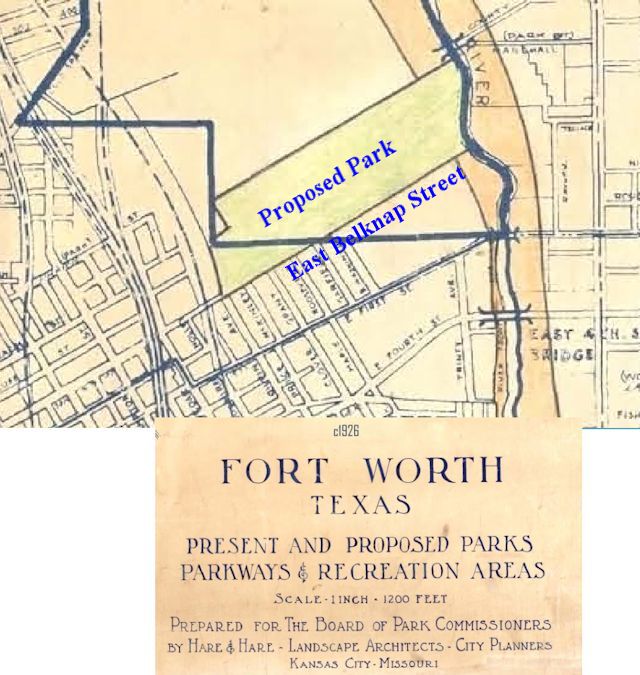

In 1926 Greenway Park was just in the planning stage. Most of the proposed park was still outside the city limits. East Belknap Street would not cross the river until about 1929. (Hare & Hare was Sidney Hare and son Herbert, who had studied under Frederick Law Olmsted, considered by many to be the father of American landscape architecture. For years Hare & Hare served as landscape consultant for Fort Worth parks, including Botanic Garden.)

In 1926 Greenway Park was just in the planning stage. Most of the proposed park was still outside the city limits. East Belknap Street would not cross the river until about 1929. (Hare & Hare was Sidney Hare and son Herbert, who had studied under Frederick Law Olmsted, considered by many to be the father of American landscape architecture. For years Hare & Hare served as landscape consultant for Fort Worth parks, including Botanic Garden.)

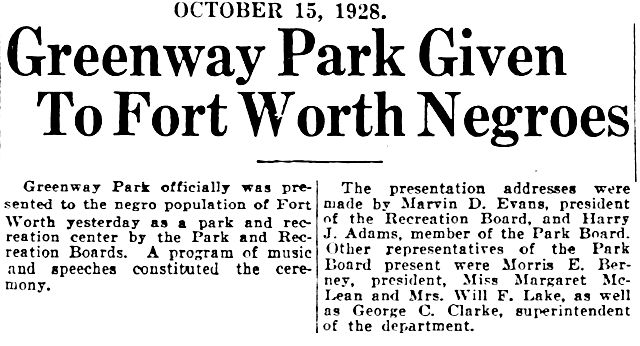

Greenway Park was developed and “given to Fort Worth Negroes” in 1928.

Greenway Park is located east of downtown in what traditionally was the center of African-American life in Fort Worth. That cross-shaped building at the bottom of the photo was Prince Hall Masonic Mosque and McDonald College of Industrial Arts. The college was named for William Madison (“Gooseneck Bill”) McDonald.

Greenway Park is located east of downtown in what traditionally was the center of African-American life in Fort Worth. That cross-shaped building at the bottom of the photo was Prince Hall Masonic Mosque and McDonald College of Industrial Arts. The college was named for William Madison (“Gooseneck Bill”) McDonald.

The park’s layout was rather formal, with a U-shaped walkway and rows of uniformly spaced trees along the long sides. The park had a tennis court, a baseball diamond, and a stone bandstand.

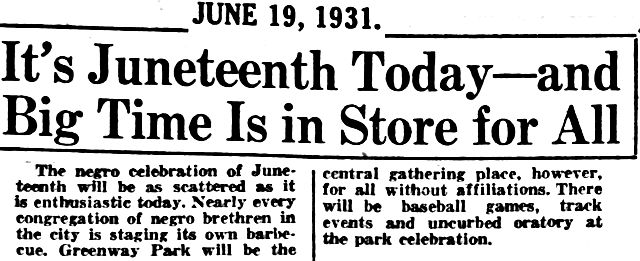

Greenway Park, as one of the city’s few African-American parks, became a center of annual Juneteenth celebrations.

In 2002 Velvin Carter recalled, “We had a lot of blacks who worked for the Swift and Armour meatpacking plants, and on the nineteenth of June, they would furnish the meat. All the black employees would meet up at Greenway Park for free barbecue.”

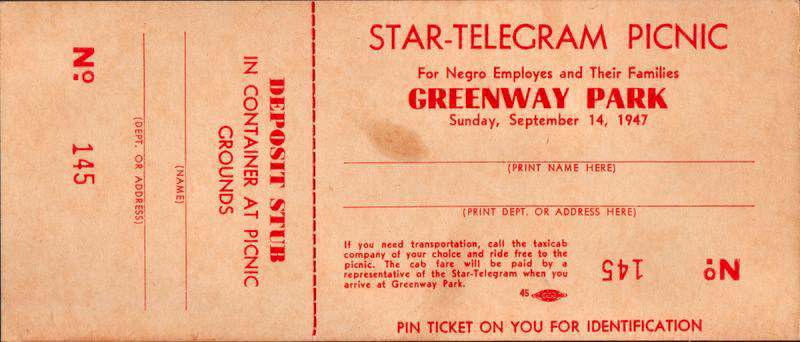

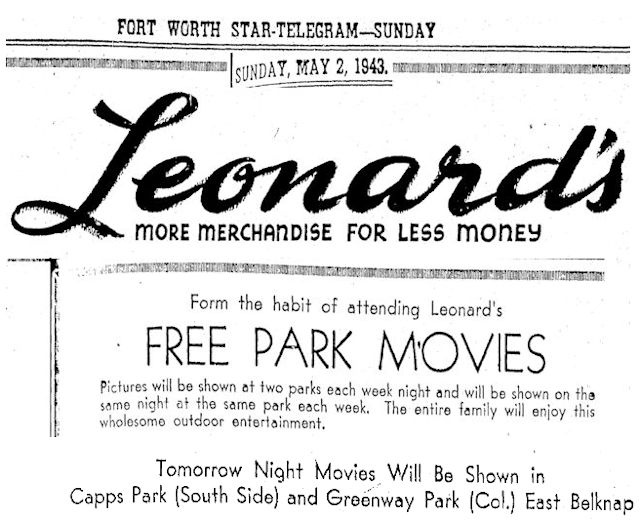

The Star-Telegram picnic for its African-American employees was held at Greenway Park. And Leonard’s Department Store sponsored “free park movies” at Greenway.

The Star-Telegram picnic for its African-American employees was held at Greenway Park. And Leonard’s Department Store sponsored “free park movies” at Greenway.

Bobby Stanton, as a youth growing up in Mosier Valley’s African-American community, commuted to I. M. Terrell High School. He remembered that Greenway was the only city park open to African Americans when he was growing up in the 1940s. (Bobby Stanton eventually was able to get into any park he wanted: He grew up to be Robert Stanton, appointed by President Clinton in 1997 to be director of the National Park Service.)

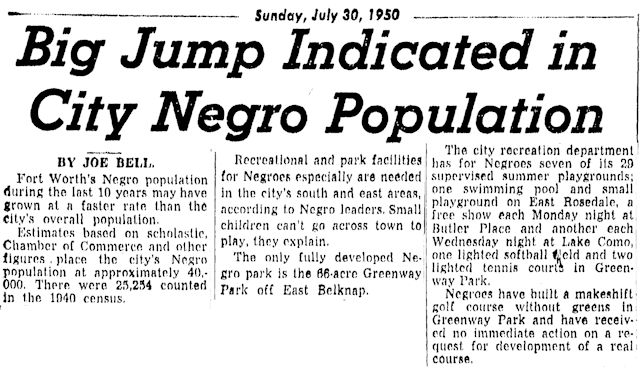

This Star-Telegram report says that in 1950 Greenway was the only “fully developed” city park for African Americans. The report says that African-American golfers had scratched out a makeshift golf course without greens in Greenway Park.

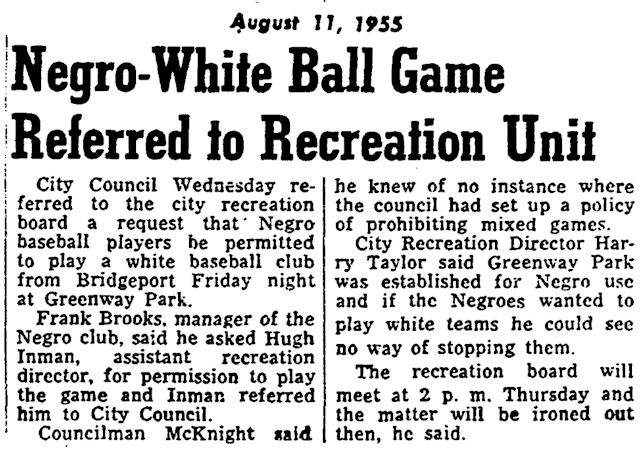

Even into the 1950s segregation was so entrenched that the idea of whites playing at an African-American park was controversial.

Even into the 1950s segregation was so entrenched that the idea of whites playing at an African-American park was controversial.

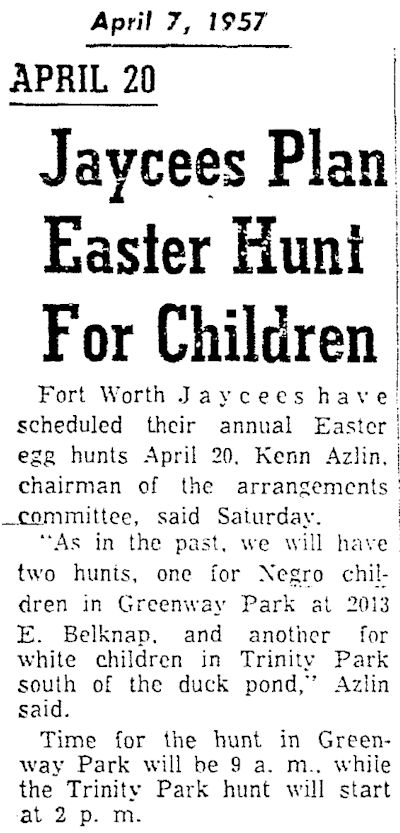

Even the Easter bunny was not colorblind. Easter egg hunts were segregated: whites at Trinity Park, blacks at Greenway Park.

Even the Easter bunny was not colorblind. Easter egg hunts were segregated: whites at Trinity Park, blacks at Greenway Park.

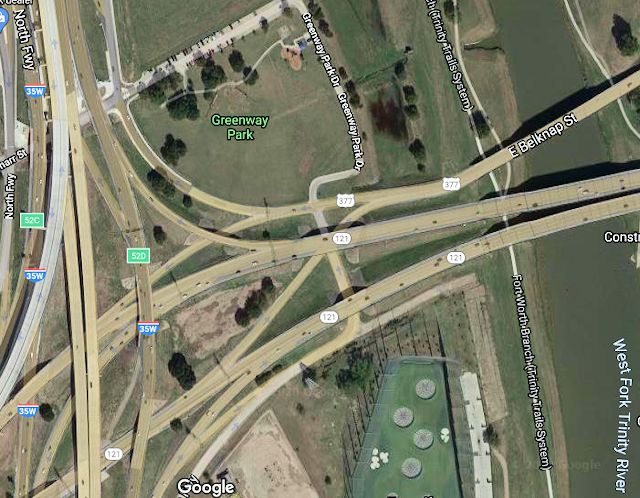

Greenway Park, like Harmon Field, fell afoul of freeways. With the extension of I-35W north, Greenway Park lost much of its acreage, and consultant Herbert Hare of Hare & Hare recommended that the remaining land be sold.

But Greenway Park survived on a reduced patch of real estate, offering a baseball field and a small playground.

But Greenway Park survived on a reduced patch of real estate, offering a baseball field and a small playground.

Today what is left of Greenway Park is squeezed between the river and the interchange of Airport Freeway and Interstate 35W. Ironically, the park’s close proximity to two freeways makes it difficult to get to on surface streets because the freeways’ connections to the park are tricky. Better leave a trail of bread crumbs.

Lincoln Park

Lincoln Park was an exception to the city’s trend of locating parks for African Americans on the East Side.

Lincoln Park is a small park on the North Side between the north and south sections of Lincoln Avenue.

Lincoln Park is a small park on the North Side between the north and south sections of Lincoln Avenue.

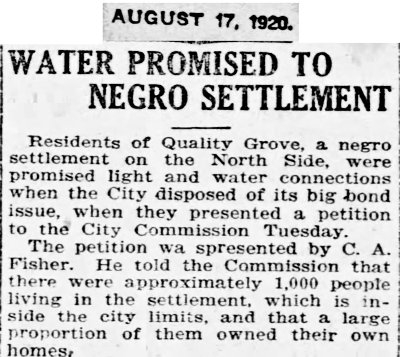

The park originally was named “Quality Grove Park” for the “Negro settlement” on the North Side.

The park originally was named “Quality Grove Park” for the “Negro settlement” on the North Side.

Residents of Quality Grove petitioned for a city park in 1930. In 1934 the city bought land along Marine Creek and Azle Road (Angle Avenue today), and in 1935 the park opened.

Residents of Quality Grove petitioned for a city park in 1930. In 1934 the city bought land along Marine Creek and Azle Road (Angle Avenue today), and in 1935 the park opened.

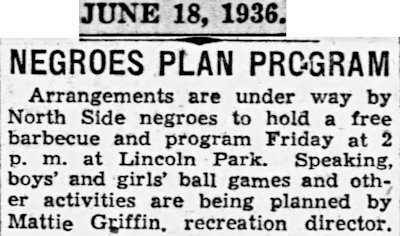

By 1936 the park had been renamed “Lincoln Park.”

By 1936 the park had been renamed “Lincoln Park.”

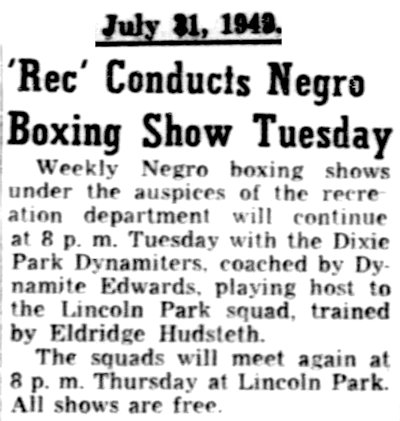

In 1949 the city’s recreation department sponsored “weekly Negro boxing shows.” Teams included those from Dixie Park and Lincoln Park.

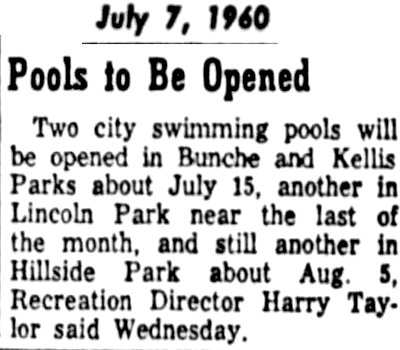

In 1960 the city added a swimming pool to Lincoln Park. That pool, like most pools in city parks, has been filled in. Today Lincoln Park has a playground area, tennis court, and baseball field.

In 1960 the city added a swimming pool to Lincoln Park. That pool, like most pools in city parks, has been filled in. Today Lincoln Park has a playground area, tennis court, and baseball field.

Lake Como Park

In the beginning Lake Como Park was not a city-designated park for African Americans.

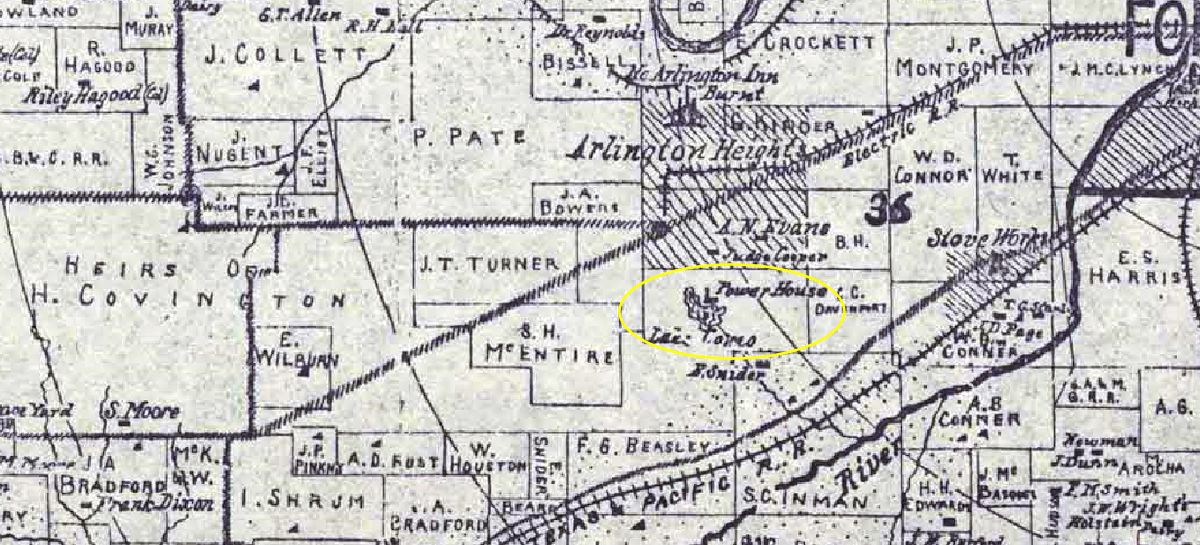

Lake Como Park (shown on this 1895 map) was created about 1890 as part of British-born developer Humphrey Barker Chamberlin’s ambitious plan to turn almost four thousand acres of prairie west of Fort Worth into an upscale suburb similar to his development in Denver. The Fort Worth suburb would be called “Arlington Heights.” Chamberlin impounded a lake and built a park around it. In the park would be (1) a power plant (using water from the lake) to supply electricity to the homes of Arlington Heights and to the streetcar line that would connect Arlington Heights to Fort Worth and (2) a trolley park—with the lake as its centerpiece—at the terminus of the streetcar line.

Lake Como Park (shown on this 1895 map) was created about 1890 as part of British-born developer Humphrey Barker Chamberlin’s ambitious plan to turn almost four thousand acres of prairie west of Fort Worth into an upscale suburb similar to his development in Denver. The Fort Worth suburb would be called “Arlington Heights.” Chamberlin impounded a lake and built a park around it. In the park would be (1) a power plant (using water from the lake) to supply electricity to the homes of Arlington Heights and to the streetcar line that would connect Arlington Heights to Fort Worth and (2) a trolley park—with the lake as its centerpiece—at the terminus of the streetcar line.

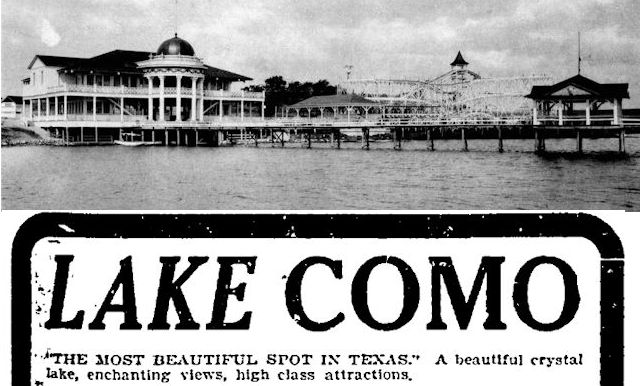

Lake Como Park’s amusement area had a pavilion, boardwalk, and rides. (Photo from Amon Carter Museum.)

Lake Como Park’s amusement area had a pavilion, boardwalk, and rides. (Photo from Amon Carter Museum.)

The trolley park enjoyed several successful years, but after the turn of the century ownership of the park was litigated for eight years, most of the park’s amusements were removed, patronage of the park declined after the city impounded Lake Worth in 1914, and by 1920 the park was being used mostly by anglers.

Meanwhile, whereas the Arlington Heights neighborhood east of the lake developed as white, the Como neighborhood west of the lake developed as African American.

After white patronage of the park declined, African Americans increasingly used Lake Como Park.

The park was especially popular for two annual events:

A parade from the Como Community Center to the park on Independence Day.

And a celebration on Juneteenth.

And a celebration on Juneteenth.

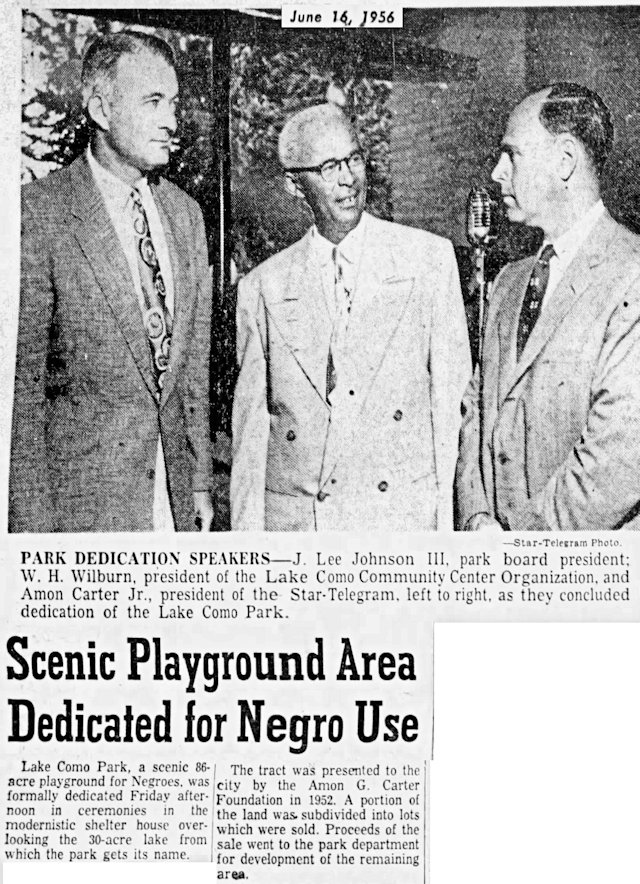

In 1952 Amon Carter, who by then owned Lake Como Park, gave the park to the city. In 1956 the city dedicated Lake Como Park for use by African Americans. Officiating at the dedication were park board president J. Lee Johnson III, Como civic leader W. H. Wilburn, and Amon Carter Jr.

In 1952 Amon Carter, who by then owned Lake Como Park, gave the park to the city. In 1956 the city dedicated Lake Como Park for use by African Americans. Officiating at the dedication were park board president J. Lee Johnson III, Como civic leader W. H. Wilburn, and Amon Carter Jr.