During its first seventy years the city of Fort Worth, like most of the South, was racially segregated but provided no parks for its African-American residents.

Douglas Park

So, in 1895 Thomas Mason, an African-American entrepreneur, bought some land and opened his own park.

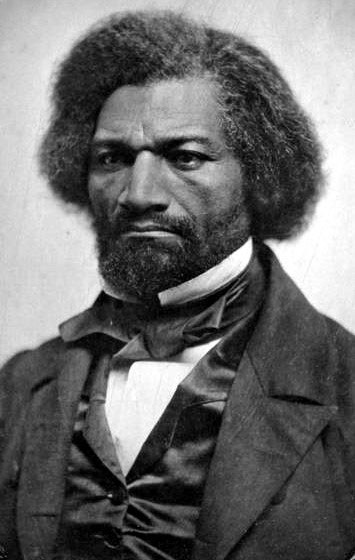

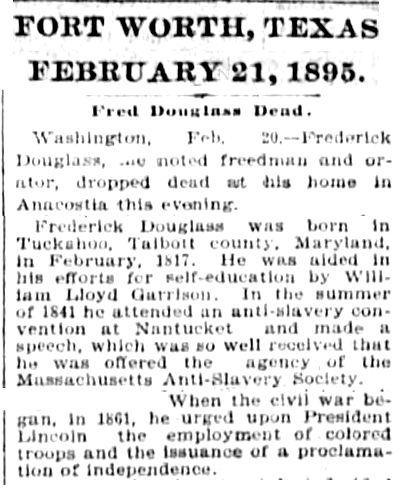

Mason named the park “Douglas Park” in honor of African-American abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass (double-s), who had died that year. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Mason named the park “Douglas Park” in honor of African-American abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass (double-s), who had died that year. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

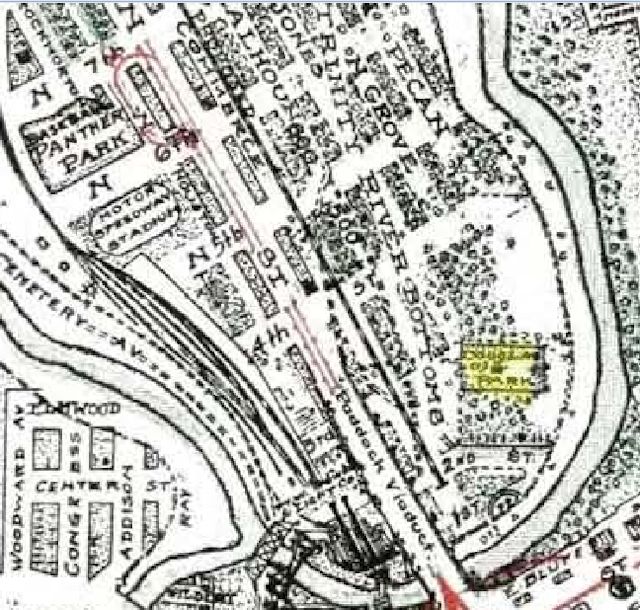

Douglas Park was not prime real estate. It was located in the Trinity River bottom northeast of the courthouse.

Douglas Park was not prime real estate. It was located in the Trinity River bottom northeast of the courthouse.

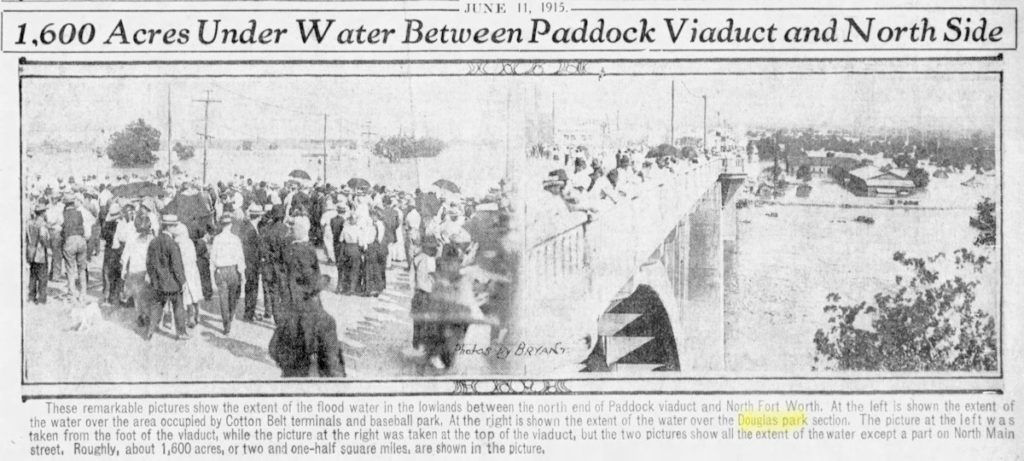

The river bottom was populated by squatters and was prone to flooding. These photos taken after the flood of 1915 show people on the Paddock Viaduct looking at water covering the near North Side river bottom, including Douglas Park.

The river bottom was populated by squatters and was prone to flooding. These photos taken after the flood of 1915 show people on the Paddock Viaduct looking at water covering the near North Side river bottom, including Douglas Park.

Among the first events held at Douglas Park in its first year was a Juneteenth celebration.

Among the first events held at Douglas Park in its first year was a Juneteenth celebration.

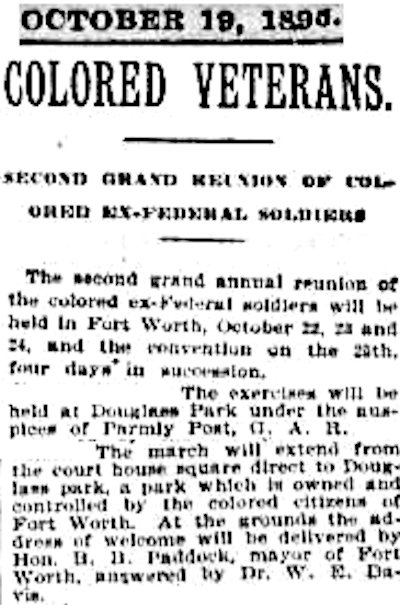

Four months later African-American Union Army veterans of the Civil War held their annual reunion at the park. The veterans were welcomed by Mayor B. B. Paddock.

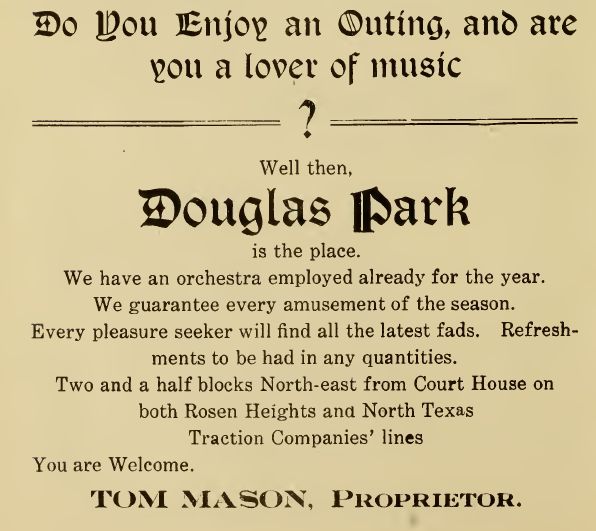

Ad is from the African-American publication History and Directory of Fort Worth in 1907.

Ad is from the African-American publication History and Directory of Fort Worth in 1907.

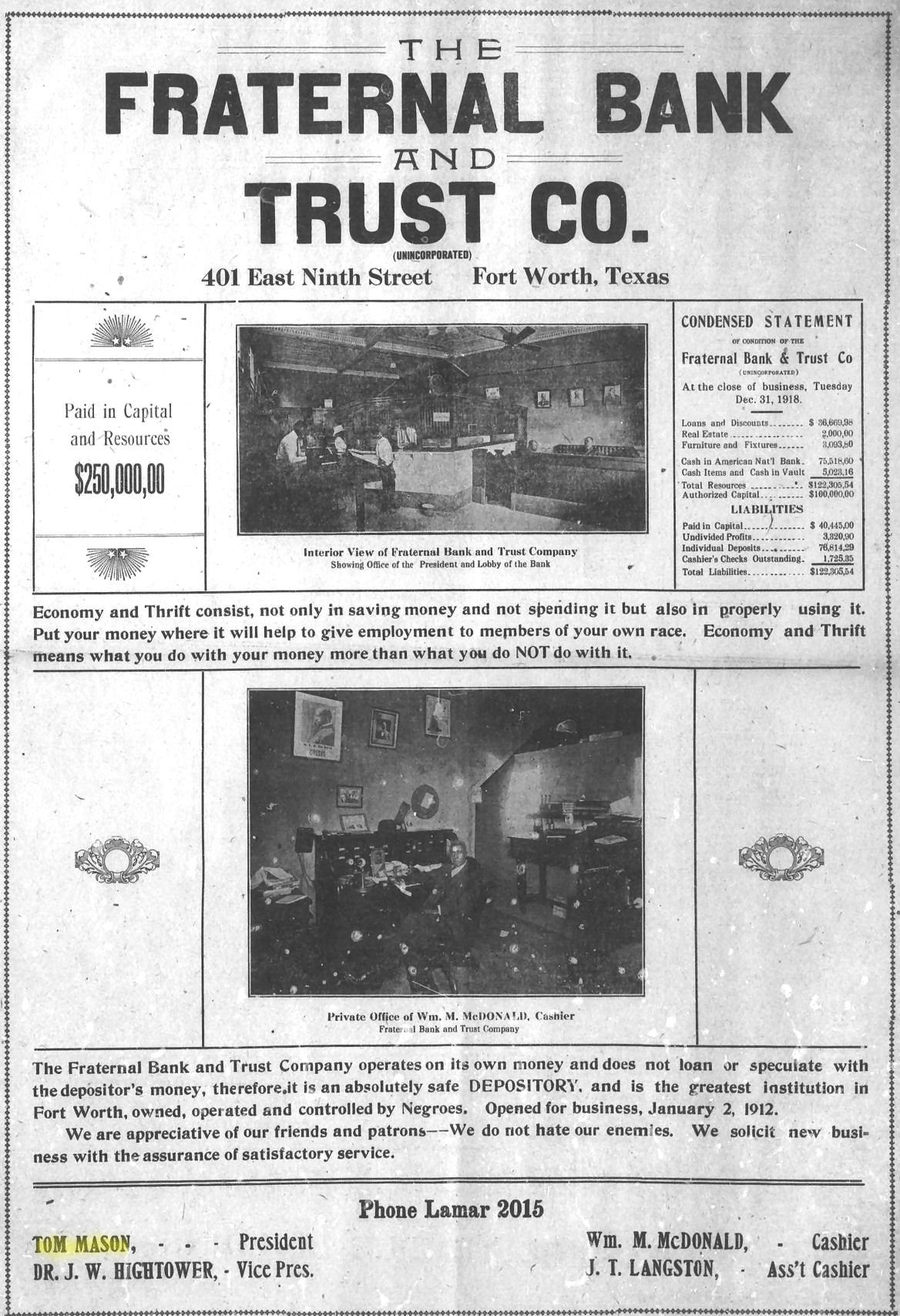

Thomas Mason was a saloonkeeper who became president of Fort Worth’s Fraternal Bank and Trust, the main depository of assets of the state’s African-American Masonic lodges. Ad is from the Dallas Express in 1919.

Thomas Mason was a saloonkeeper who became president of Fort Worth’s Fraternal Bank and Trust, the main depository of assets of the state’s African-American Masonic lodges. Ad is from the Dallas Express in 1919.

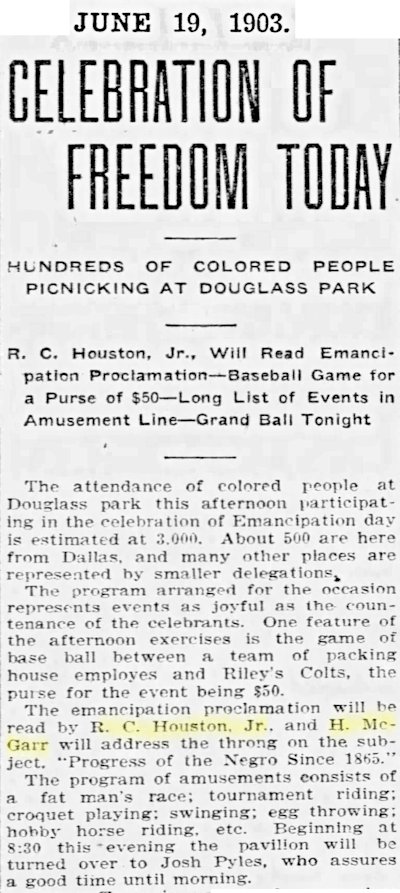

The Juneteenth celebration was the grandest event on the calendar at Douglas Park. Excursion trains brought in people—some of them former slaves—from Louisiana to El Paso. A parade was held from downtown to the park. The mayor welcomed the crowd, the Emancipation Proclamation was read, and speeches were given. For example, in 1903 three thousand people listened as undertaker R. C. Houston Jr. read the proclamation, and Hiram McGar (see below) spoke on “Progress of the Negro Since 1865.”

The Juneteenth celebration was the grandest event on the calendar at Douglas Park. Excursion trains brought in people—some of them former slaves—from Louisiana to El Paso. A parade was held from downtown to the park. The mayor welcomed the crowd, the Emancipation Proclamation was read, and speeches were given. For example, in 1903 three thousand people listened as undertaker R. C. Houston Jr. read the proclamation, and Hiram McGar (see below) spoke on “Progress of the Negro Since 1865.”

Note that the park had a pavilion and baseball field.

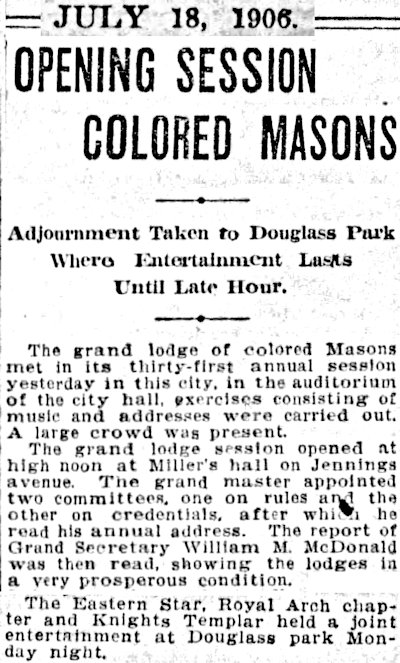

In 1906 the “grand lodge of colored Masons” held its “annual session” in Fort Worth. Grand Secretary William Madison (“Gooseneck Bill”) McDonald reported the Masonic lodges to be in “very prosperous condition.” Afterward the Masons held an entertainment at Douglas Park.

In 1906 the “grand lodge of colored Masons” held its “annual session” in Fort Worth. Grand Secretary William Madison (“Gooseneck Bill”) McDonald reported the Masonic lodges to be in “very prosperous condition.” Afterward the Masons held an entertainment at Douglas Park.

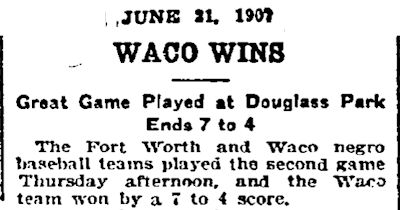

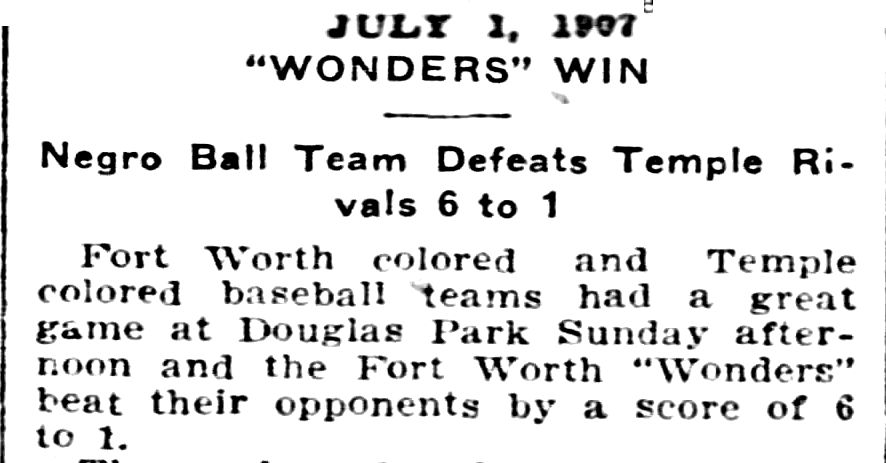

Early in the twentieth century Douglas Park’s baseball field was one of the few open to African Americans.

Early in the twentieth century Douglas Park’s baseball field was one of the few open to African Americans.

The city police department commissioned African-American “special officers” to patrol Douglas Park. Special officers were quasi-official, allowed to wear a badge and carry a gun and billy club. One such special officer was Jeff Daggett, son of E. B. Daggett and an African-American slave.

The park was popular with African-American churches, lodges (International Order of Knights and Daughters of Tabor, Odd Fellows, Prince Hall Masons), and students. Activities included masked balls, picnics, Easter egg hunts, cakewalks, rabbit chases, and exhibitions of military drilling.

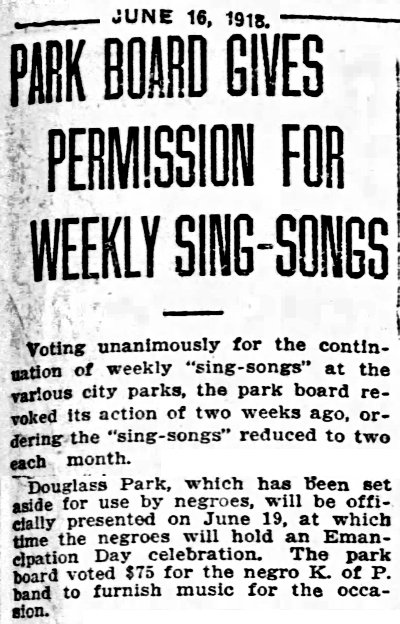

In 1918 Thomas Mason sold the park to the city. Music for the dedication was provided by the band of the Key West lodge of the Knights of Pythias, an African-American lodge that met on East 2nd Street in the African-American downtown.

At first the city maintained Douglas Park for African Americans. But patronage declined so much that in 1920 the city sold the property to the electric company.

That deal, too, was short-lived. In 1922 the city rebought Douglas Park with plans to develop the land as a municipal athletic field for the entire city, which would end the park’s status as African American.

In May 1923 Worth Field municipal athletic field opened but not on the site of Douglas Park. Instead Worth Field was located adjacent to LaGrave Field.

In May 1923 Worth Field municipal athletic field opened but not on the site of Douglas Park. Instead Worth Field was located adjacent to LaGrave Field.

Whites began to use Douglas Park.

Amateur baseball leagues were still using Douglas Park in 1924, but gradually white squatters in the river bottom dissuaded people, especially African Americans, from using the park. So, the city stopped maintaining Douglas Park and for several years was undecided about the park’s future: Should Douglas Park again be an African-American park or serve the white community?

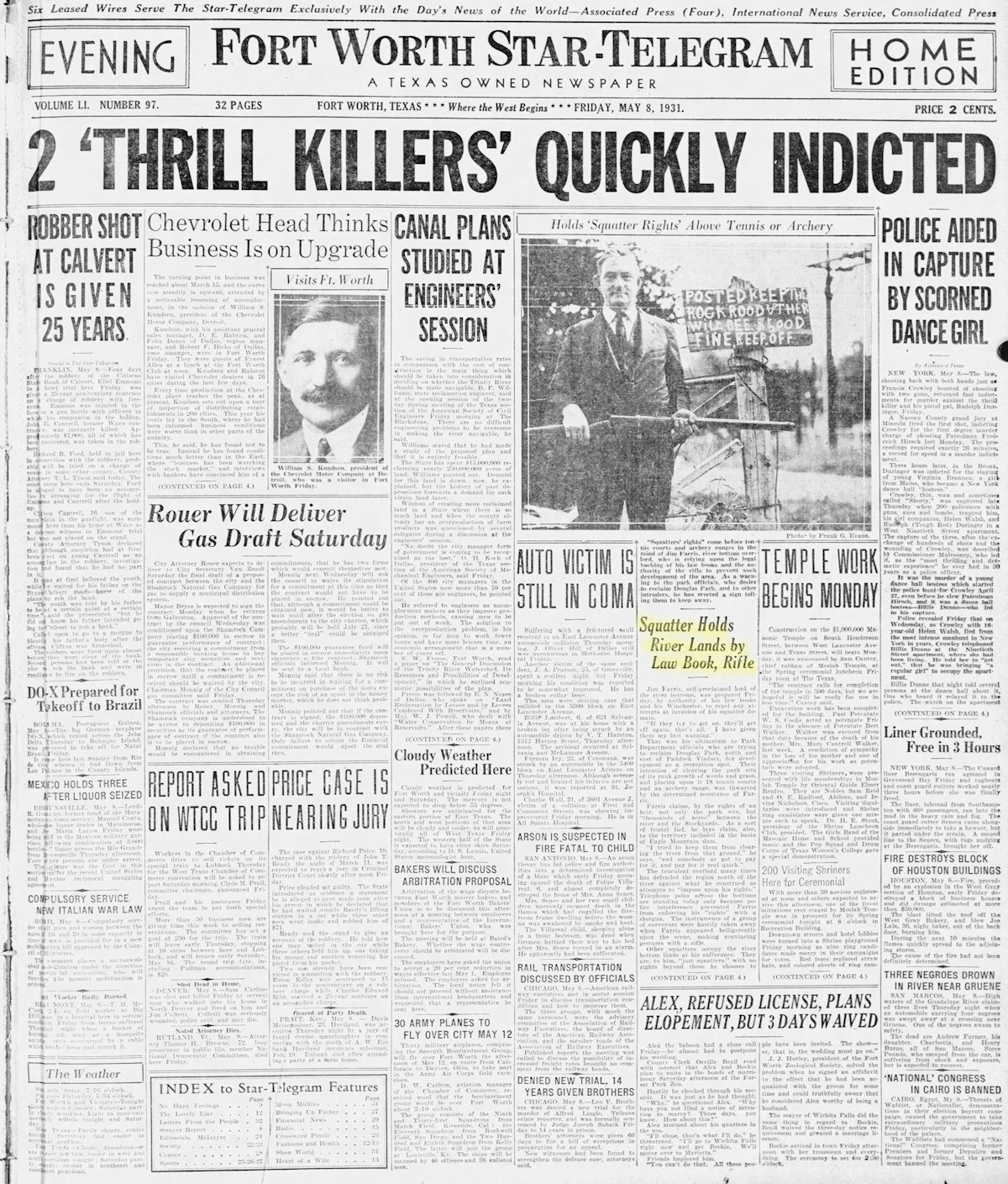

Fast-forward to 1931. The city parks department announced that it planned to clean up Douglas Park, and the city recreation department announced that it would install tennis courts and an archery range in the park, which apparently would reopen as a white park. (By 1931 the city had opened three parks for African Americans [see Part 2].)

That’s when the city ran up against Jim Farris. Farris was a squatter who lived in the river bottom near the park in a whitewashed shack made of salvaged lumber and flattened tin cans. Farris, who said he had known Jesse James, Cole Younger, and Robert Ford, claimed that Douglas Park belonged to him as administrator of a Spanish land grant that extended north to the stockyards. Holding a Winchester rifle, he had run off surveyors and crews trying to install telephone poles in the river bottom. He tolerated other white squatters in the river bottoms as “tenants” who enjoyed only the rights he bestowed upon them.

That’s when the city ran up against Jim Farris. Farris was a squatter who lived in the river bottom near the park in a whitewashed shack made of salvaged lumber and flattened tin cans. Farris, who said he had known Jesse James, Cole Younger, and Robert Ford, claimed that Douglas Park belonged to him as administrator of a Spanish land grant that extended north to the stockyards. Holding a Winchester rifle, he had run off surveyors and crews trying to install telephone poles in the river bottom. He tolerated other white squatters in the river bottoms as “tenants” who enjoyed only the rights he bestowed upon them.

As for the city, he dared it to try to develop the park.

Pointing to a stack of law books in his shack, he said, “This is where I get my information.” Pointing to two loaded rifles on the wall, he said, “And this is where I get my authority.”

The parks department and the recreation department huddled and then allowed as how the city was in no hurry to develop Douglas Park and would leave it—and its squatter king—in their natural state.

After that, Douglas Park fell out of the news and into obscurity.

McGar Park

By 1907 Fort Worth’s African Americans had a second park: McGar Park.

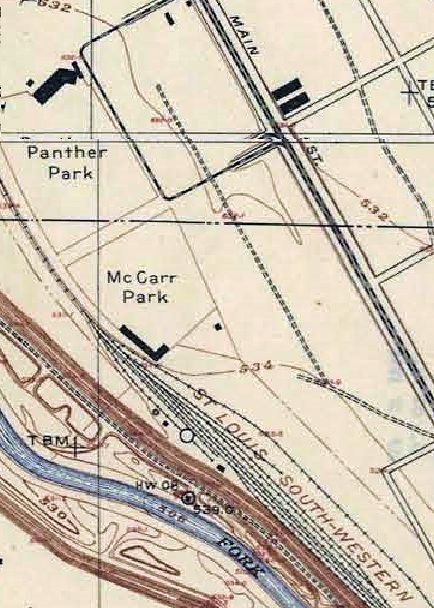

This map of 1915 locates (and misspells) McGar Park just south of Panther Park.

This map of 1915 locates (and misspells) McGar Park just south of Panther Park.

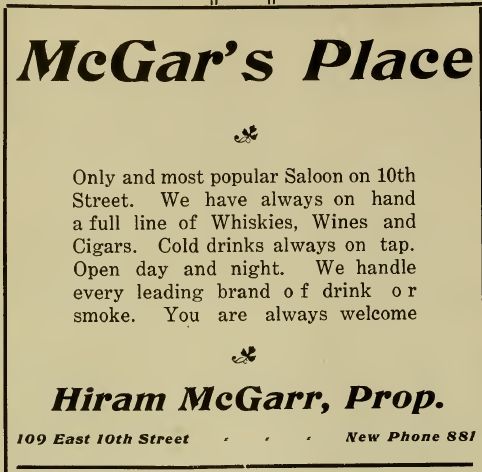

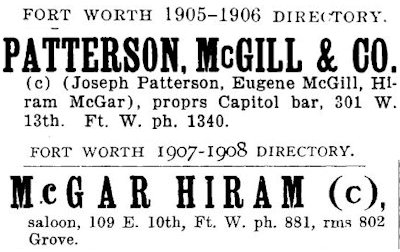

Hiram McGar, like Thomas Mason, was a saloonkeeper in the African-American community that developed on the eastern edge of downtown. In 1913 he owned a saloon on East Jones Street during one of the city’s ugliest racial episodes. Disgruntled gambler Tom Lee went on a vengeful shooting spree, killing an African-American gambler in McGar’s saloon and later a white police officer and wounding three other people. A white mob retaliated by rampaging through the black community damaging property, including McGar’s saloon.

Hiram McGar, like Thomas Mason, was a saloonkeeper in the African-American community that developed on the eastern edge of downtown. In 1913 he owned a saloon on East Jones Street during one of the city’s ugliest racial episodes. Disgruntled gambler Tom Lee went on a vengeful shooting spree, killing an African-American gambler in McGar’s saloon and later a white police officer and wounding three other people. A white mob retaliated by rampaging through the black community damaging property, including McGar’s saloon.

Ad is from History and Directory of Fort Worth in 1907.

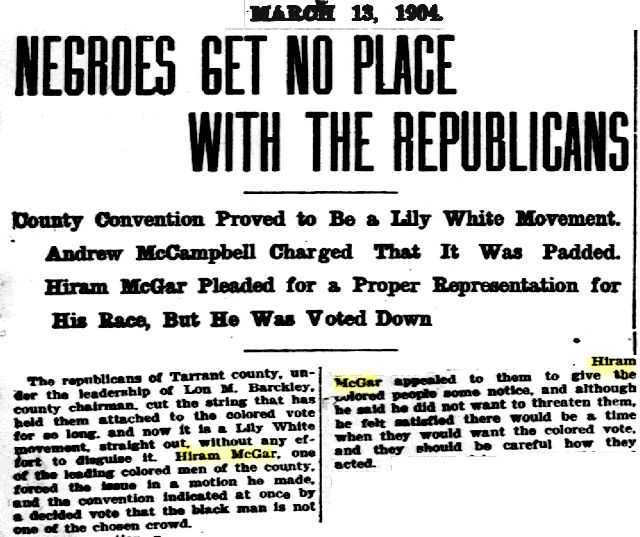

Hiram McGar also was active in Republican politics in the Third Ward (sometimes called the “bloody Third”), which included Hell’s Half Acre. In 1904 he asked that African Americans be represented at the county convention. His motion was defeated.

Hiram McGar also was active in Republican politics in the Third Ward (sometimes called the “bloody Third”), which included Hell’s Half Acre. In 1904 he asked that African Americans be represented at the county convention. His motion was defeated.

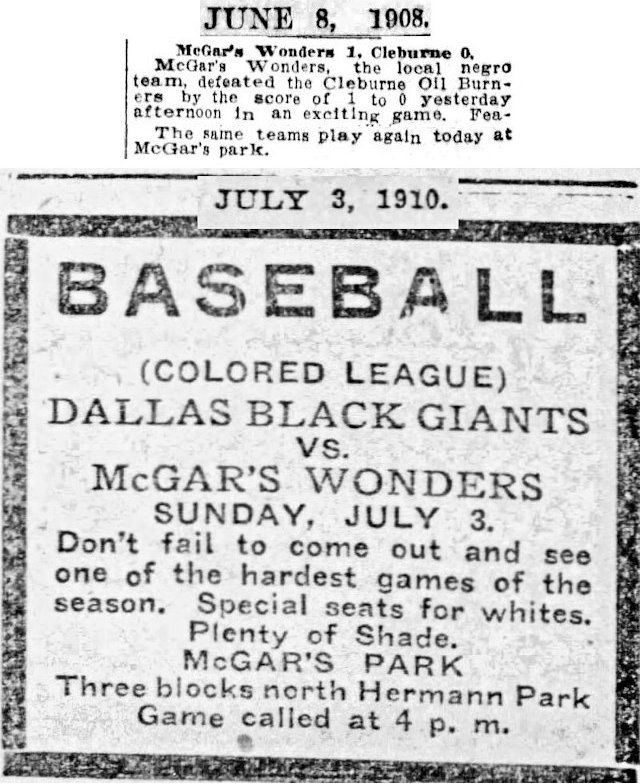

By about 1907 McGar had become interested in baseball as a commercial venture.

By about 1907 McGar had become interested in baseball as a commercial venture.

Dr. Richard Selcer in A History of Fort Worth in Black & White: 165 Years of African-American Life writes of McGar: “Sometime around the turn of the century he organized the first African-American team in Fort Worth.” That team, McGar’s Wonders, competed in the Lone Star Colored Baseball League, organized in 1897.

Whereas Douglas Park was largely a participants park, McGar Park was an observers park: People went to McGar Park to watch other people compete in sports.

Sometimes McGar’s Wonders played at Douglas Park.

Sometimes McGar’s Wonders played at Douglas Park.

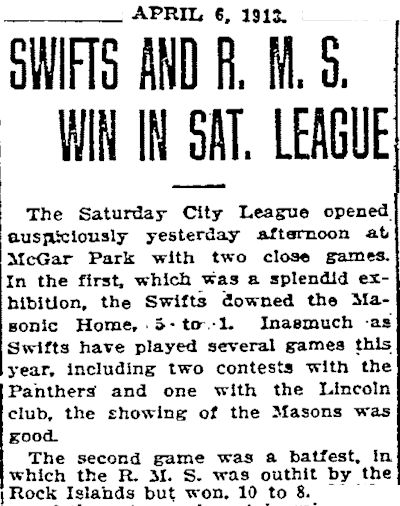

But by 1910 McGar Park was hosting white teams as well. In April 1913 a team from the Swift packing plant beat the Masonic Home team, and the R.M.S. (Railway Mail Service) team beat the Rock Island team.

But by 1910 McGar Park was hosting white teams as well. In April 1913 a team from the Swift packing plant beat the Masonic Home team, and the R.M.S. (Railway Mail Service) team beat the Rock Island team.

“Lincoln club” may refer to the Lincoln, Nebraska team of the Western League.

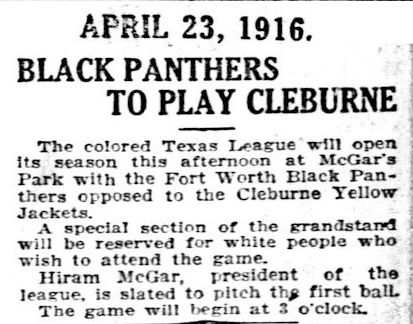

Selcer writes, “When the Lone Star League folded, McGar still owned both the Wonders and the stadium, and in 1913 he helped organize the Colored Baseball League of Texas and Oklahoma with the Wonders one of the six teams.

Selcer writes, “When the Lone Star League folded, McGar still owned both the Wonders and the stadium, and in 1913 he helped organize the Colored Baseball League of Texas and Oklahoma with the Wonders one of the six teams.

“McGar was the most experienced baseball man among the owners. In 1916 he was elected president of the League. A new league required a new name for the Wonders, so they became the Black Panthers, hoping to cash in on the popularity of the local white team, the Cats,” which more formally were the “Panthers.”

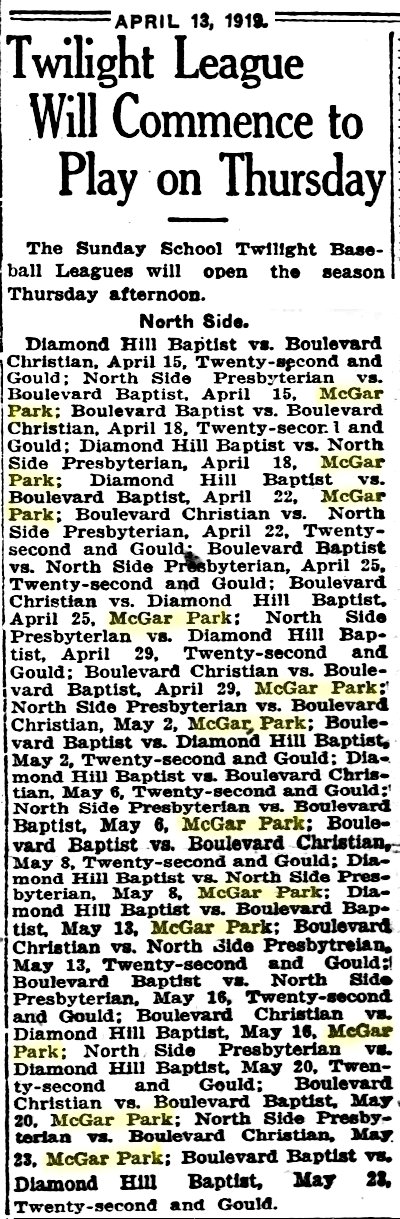

McGar Park also became a popular site for games between North Side churches.

McGar Park also became a popular site for games between North Side churches.

In 1919 the “Colored League” reorganized. Each team was located in a city that hosted a (white) Texas League team, and each black team played at the white park when the white team was on the road. That was good for the Black Panthers because in 1919 McGar Park was replaced by the motordrome. So, the Black Panthers moved north to Panther Park.

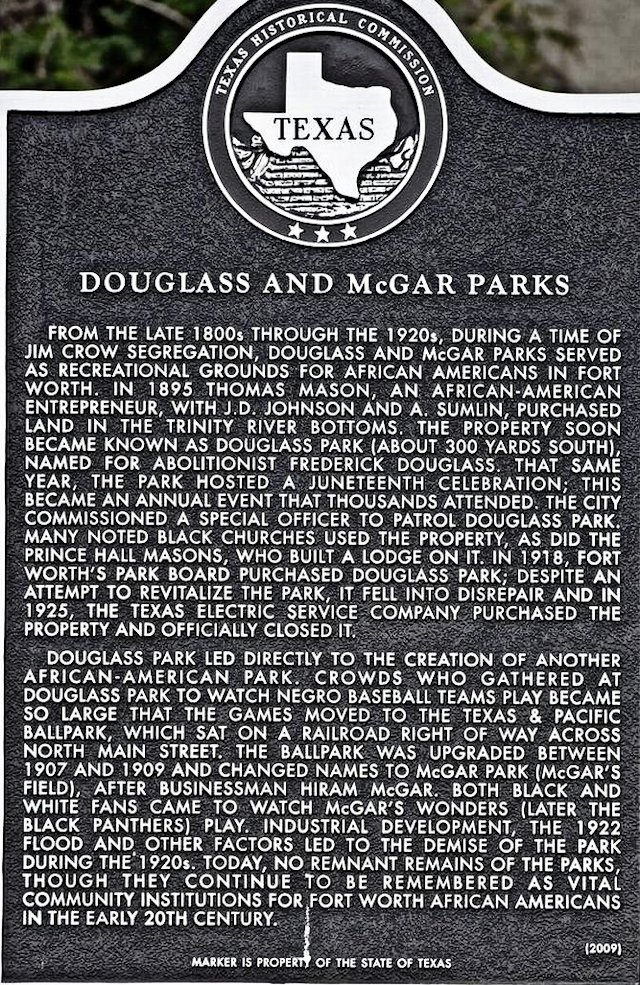

The plot of ground where McGar Park stood had a rich sports history. This marker at LaGrave Field says McGar Park was located on “the Texas & Pacific ballpark, which sat on a railroad right of way across North Main Street” (from Douglas Park). But the only Texas & Pacific park I know of was on the railroad reservation south of downtown. However, the St. Louis-Southwestern (Cotton Belt) railroad’s yard and tracks were located adjacent to McGar Park. I think McGar Park was built on the land formerly occupied by Prospect Park (1902), although I have found only vague locations given for Prospect Park: “near Hermann’s in North Fort Worth” (Hermann Park was on North Main Street between Northwest 1st and 3rd streets) and “near the Cotton Belt depot.” The known location of McGar Park fits the suspected location of Prospect Park: north of Hermann Park and near the Cotton Belt depot. After the motordrome replaced McGar Park in 1919, the motordrome was in business only one year.

The plot of ground where McGar Park stood had a rich sports history. This marker at LaGrave Field says McGar Park was located on “the Texas & Pacific ballpark, which sat on a railroad right of way across North Main Street” (from Douglas Park). But the only Texas & Pacific park I know of was on the railroad reservation south of downtown. However, the St. Louis-Southwestern (Cotton Belt) railroad’s yard and tracks were located adjacent to McGar Park. I think McGar Park was built on the land formerly occupied by Prospect Park (1902), although I have found only vague locations given for Prospect Park: “near Hermann’s in North Fort Worth” (Hermann Park was on North Main Street between Northwest 1st and 3rd streets) and “near the Cotton Belt depot.” The known location of McGar Park fits the suspected location of Prospect Park: north of Hermann Park and near the Cotton Belt depot. After the motordrome replaced McGar Park in 1919, the motordrome was in business only one year.

Hi there! Really enjoy this site and the care you put into these posts. I work for a group that recently purchased some land on Panther Island and we want to engage a historical study to better understand the historical significance of the area so that we can incorporate it into our future project. Is this something that you would have any interest in? Or is there another colleague of yours that may have an interest? Thanks so much!

Thanks for visiting this site. Unfortunately the author, Mike Nichols, has passed away. We are currently working to find a solution to best preserve this informative website.

Hi! This is a great site. I am wondering where you got a particular picture and what the permission is for using it. It is an ad newspaper clipping for Maddox, Ellison & Co.

Thanks, Megan. Without seeing the Maddox, Ellison & Co. ad I can’t say where I got it. Newspaper or city directory, I suspect. You certainly don’t have to ask my permission.