Here are two more multipurpose parks of yore (see Part 1):

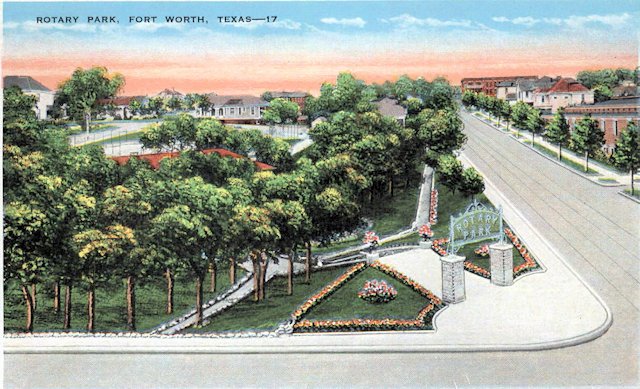

Rotary Park

At the intersection of Summit Avenue and West 7th Street sits a 7-Eleven convenience store.

At the intersection of Summit Avenue and West 7th Street sits a 7-Eleven convenience store.

But for more than forty years that block was occupied by Rotary Park. This view is to the south along Summit Avenue.

But for more than forty years that block was occupied by Rotary Park. This view is to the south along Summit Avenue.

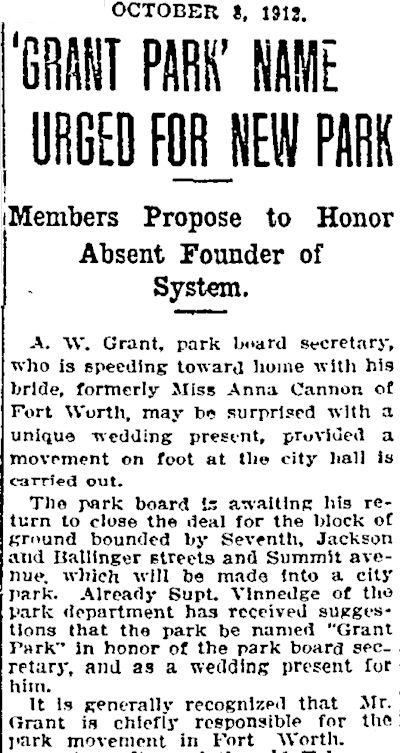

The park was created in 1912 as “A. W. Grant Park,” named in honor of a park board member. In 1912 near the park were several mansions of Quality Hill.

The park was created in 1912 as “A. W. Grant Park,” named in honor of a park board member. In 1912 near the park were several mansions of Quality Hill.

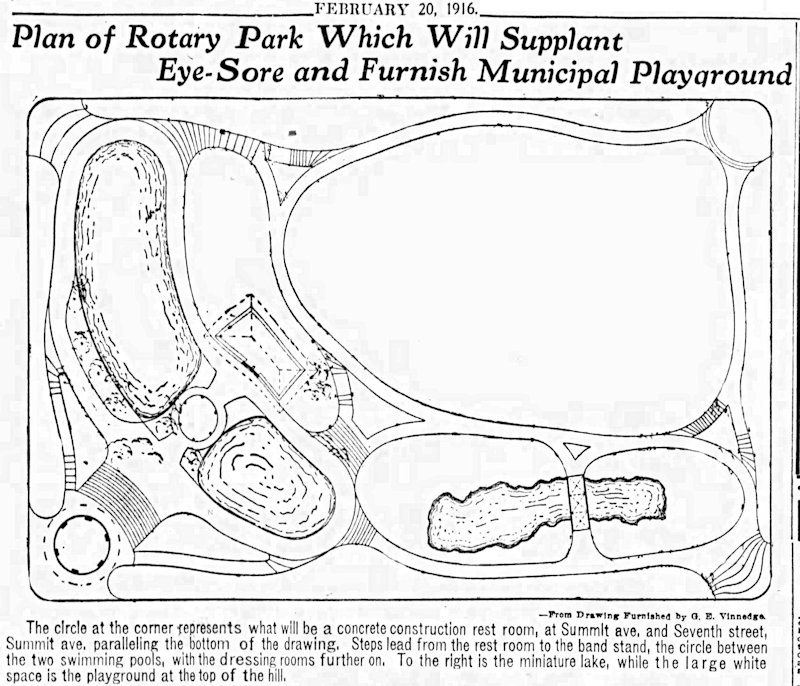

In 1916 the name of the park was changed—with Grant’s blessing—to “Rotary Park” after members of the Rotary Club donated money to make major improvements to the park.

In 1916 the name of the park was changed—with Grant’s blessing—to “Rotary Park” after members of the Rotary Club donated money to make major improvements to the park.

The park was terraced, with two “sand beach” pools, a larger pond spanned by a bridge, playground, pergola, bandstand, dressing rooms, tennis courts, and rose garden. The park also housed the city parks department office.

The park was terraced, with two “sand beach” pools, a larger pond spanned by a bridge, playground, pergola, bandstand, dressing rooms, tennis courts, and rose garden. The park also housed the city parks department office.

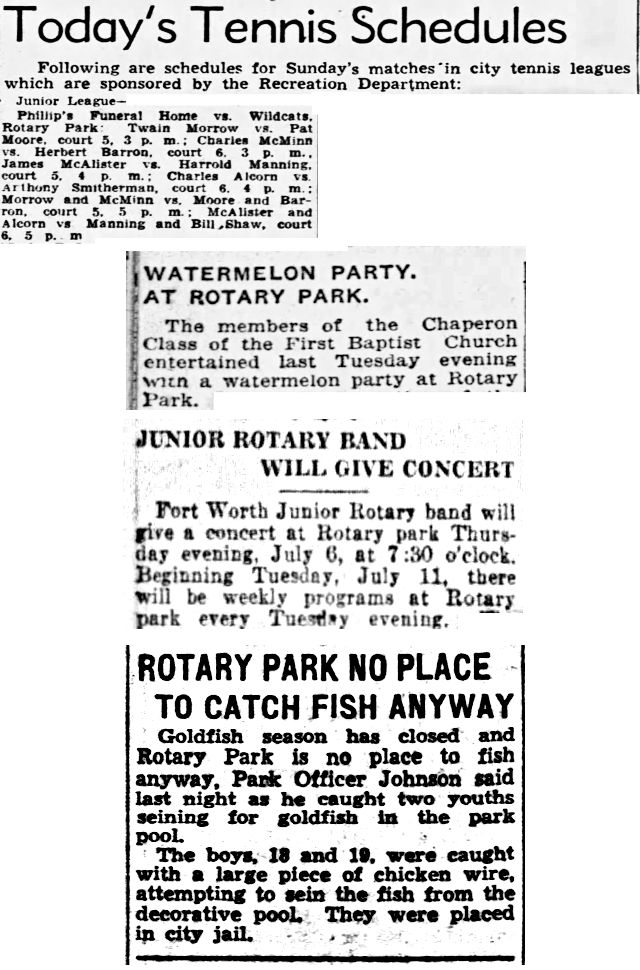

The park was small but centrally located. It was popular for tennis, basketball, volleyball, parties, concerts—and fishing by illicit anglers.

The park was small but centrally located. It was popular for tennis, basketball, volleyball, parties, concerts—and fishing by illicit anglers.

But in 1954 the Star-Telegram reported that the park was little used. The city sold the park the next year to Frank Kent. A new headquarters for the parks department was built at Botanic Garden. Kent cleaned up the neglected park.

But by 1963 the Rotary Park tennis courts were being used as a parking lot.

In 2014 the Rotary Club gave Fort Worth a park within a park as Rotary Plaza opened in Trinity Park. The roundabout (yellow circle on satellite photo) of Rotary Plaza contains the 1916 Rotary monument from the original Rotary Park.

In 2014 the Rotary Club gave Fort Worth a park within a park as Rotary Plaza opened in Trinity Park. The roundabout (yellow circle on satellite photo) of Rotary Plaza contains the 1916 Rotary monument from the original Rotary Park.

Casino Park

Eight miles northwest of Rotary Park, in 1917 the city of Fort Worth opened a municipal beach at Lake Worth.

Eight miles northwest of Rotary Park, in 1917 the city of Fort Worth opened a municipal beach at Lake Worth.

Ten years later Casino Park opened on the municipal beach. The park was operated by a company licensed by the city.

Ten years later Casino Park opened on the municipal beach. The park was operated by a company licensed by the city.

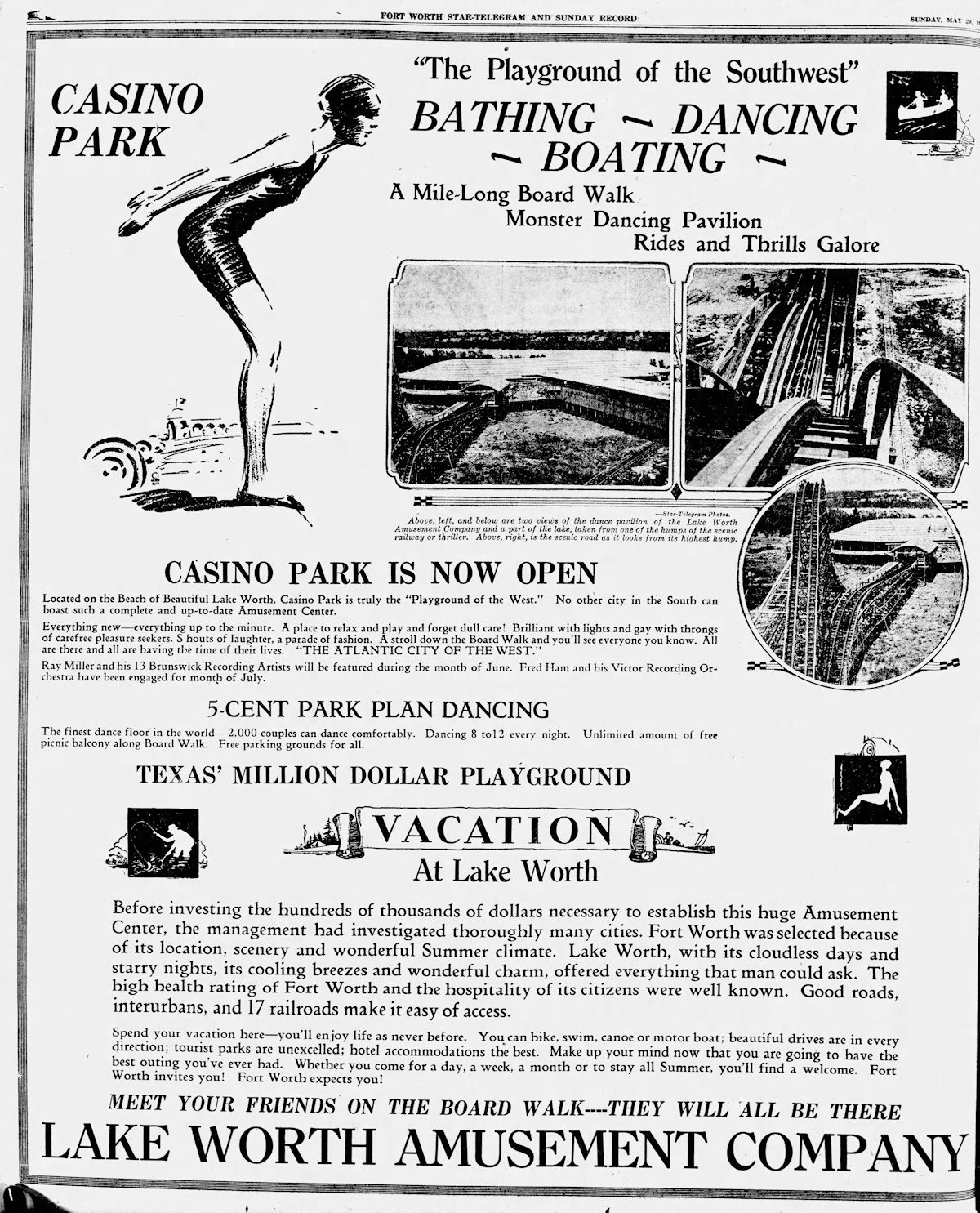

Casino Park billed itself as “the playground of the Southwest.” The park was a sandy Six Flags. It featured a midway with rides such as a tilt-a-whirl, dodge-’em cars, merry-go-round, and the “Bug-a-Boo” tunnel train. The feature ride was the mile-long Thriller (largest roller coaster in the Southwest at the time). There was a 1,500-foot-long boardwalk (longest west of Atlantic City), a swimming beach (of course), motorboat rentals, eighty-five concession vendors.

Casino Park billed itself as “the playground of the Southwest.” The park was a sandy Six Flags. It featured a midway with rides such as a tilt-a-whirl, dodge-’em cars, merry-go-round, and the “Bug-a-Boo” tunnel train. The feature ride was the mile-long Thriller (largest roller coaster in the Southwest at the time). There was a 1,500-foot-long boardwalk (longest west of Atlantic City), a swimming beach (of course), motorboat rentals, eighty-five concession vendors.

Oh, and a three hundred-pound caged gorilla named “Big Boy.”

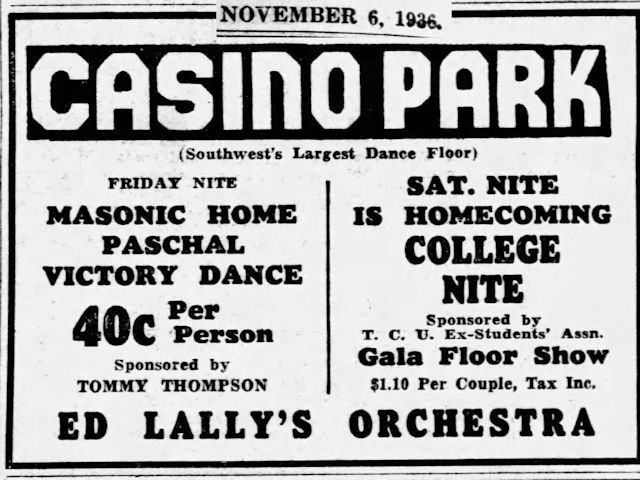

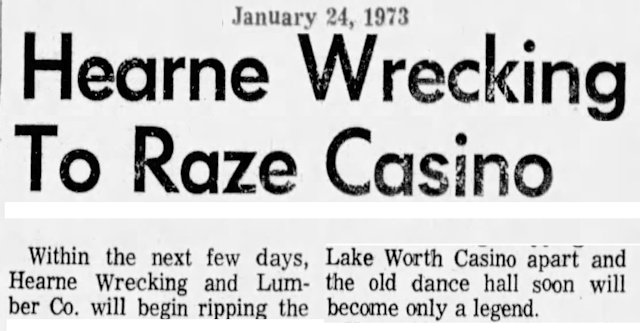

The casino that gave the park its name was for dancing, not dicing. The casino was a cavernous ballroom: “2,000 couples can dance comfortably.” (For scale, the entire population of Edgecliff Village could have danced the night away.) Two lighted crystal balls hung from the ceiling and cast multicolored speckles of light onto the dancers. Bedazzled, some couples became engaged on that dance floor.

The park was popular from the beginning. For example, several hundred Texas & Pacific railroad employees held a picnic at the park in 1927 to mark the fifty-first anniversary of the railroad’s arrival in Fort Worth. In attendance was president John L. Lancaster.

The park was popular from the beginning. For example, several hundred Texas & Pacific railroad employees held a picnic at the park in 1927 to mark the fifty-first anniversary of the railroad’s arrival in Fort Worth. In attendance was president John L. Lancaster.

A staple of the park was beauty contests. Among the contestants in a beauty revue in 1927 was Miss Oak Cliff.

A staple of the park was beauty contests. Among the contestants in a beauty revue in 1927 was Miss Oak Cliff.

By June 17, 1929 about two million people had visited Casino Park since its opening. At dawn that morning two night watchmen discovered a fire on the boardwalk of a park built with one million feet of lumber. Swept by a brisk wind, the fire spread and destroyed most of the wooden park.

By June 17, 1929 about two million people had visited Casino Park since its opening. At dawn that morning two night watchmen discovered a fire on the boardwalk of a park built with one million feet of lumber. Swept by a brisk wind, the fire spread and destroyed most of the wooden park.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “All that is left of the many entertainment features of Casino Park is the boardwalk that led to the beach, a section of the Thriller, Blue Beard’s Castle and the merry-go-round. Almost one mile of the boardwalk is in ashes. On each were the picnic balconies and numerous concessions, fun rides and fun houses, all destroyed in the flames.”

Big Boy the gorilla died in the fire.

Damage was estimated at $600,000 ($9 million today).

The company that operated the park vowed to build.

And it did.

And it did.

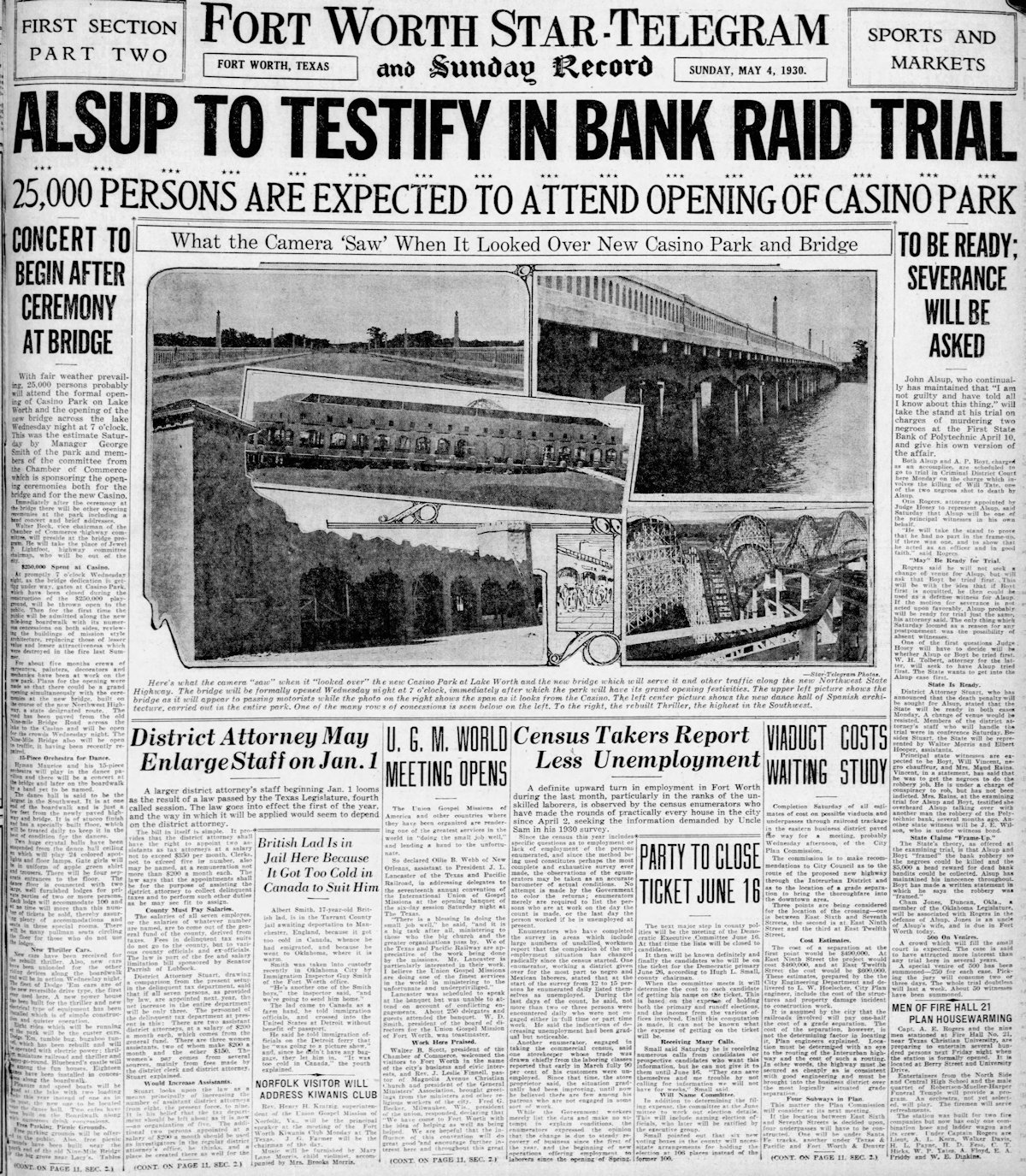

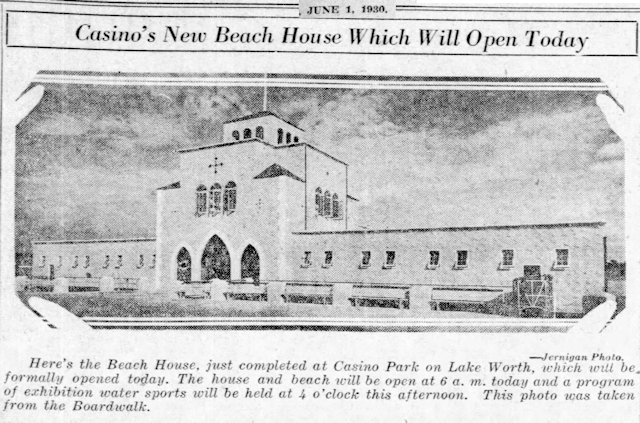

In May 1930 as ex-police officer John Alsup testified in his trial for murdering two men he tried to frame for the robbery of First State Bank of Polytechnic, Fort Worth held a double celebration to mark the opening of the rebuilt Casino Park and the bridge carrying State Highway 34 (Jacksboro Highway) over the lake.

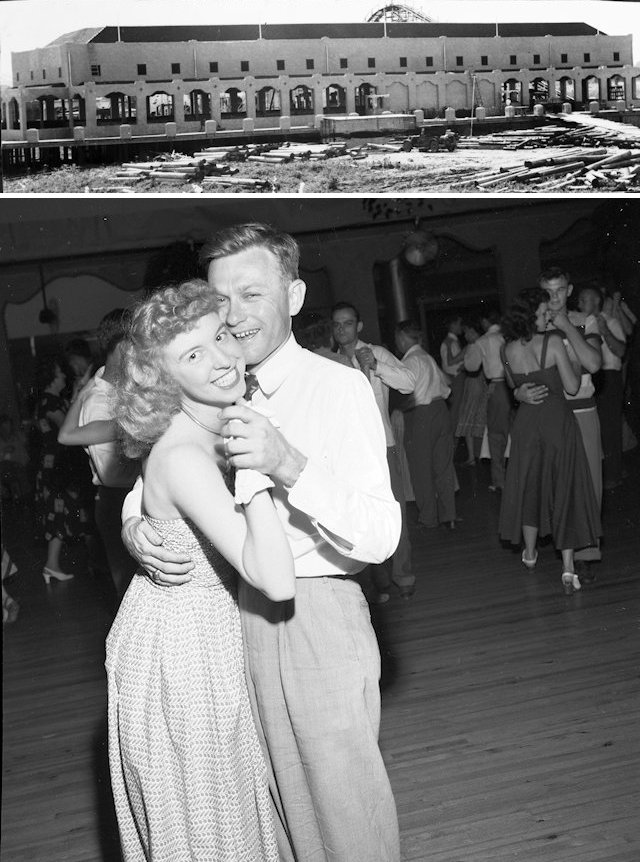

The rebuilt park’s Spanish mission architecture is seen in the new beach house, which could accommodate three thousand wet people. The Star-Telegram reported that a “shipment of all-wool bathing suits has been received.”

The rebuilt park’s Spanish mission architecture is seen in the new beach house, which could accommodate three thousand wet people. The Star-Telegram reported that a “shipment of all-wool bathing suits has been received.”

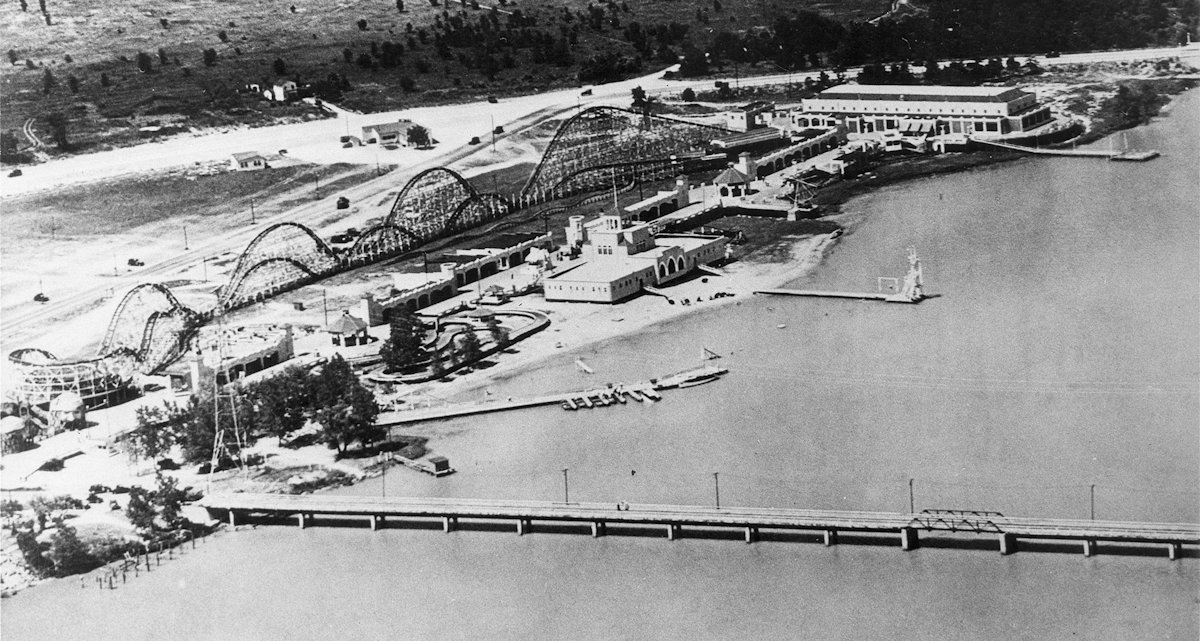

This aerial photo shows the rebuilt park with Nine-Mile Bridge in the foreground and Jacksboro Highway beyond the park. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

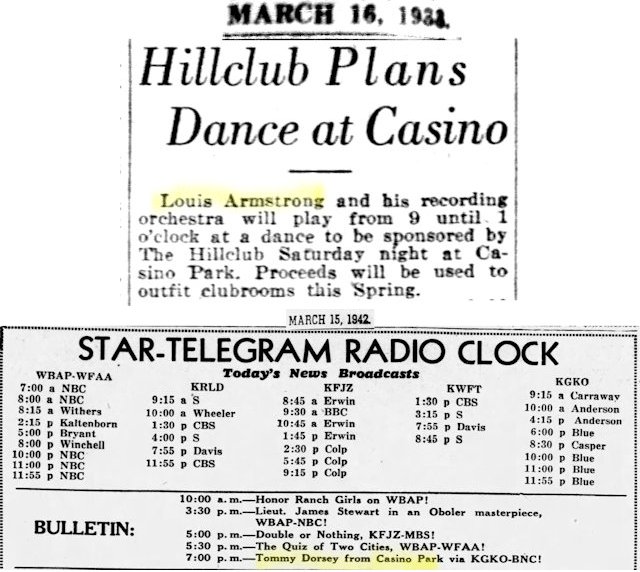

The ballroom attracted some of the most popular musicians and singers, including Guy Lombardo, Tommy Dorsey, Frank Sinatra, Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, the Ink Spots, Harry James, and Louis Armstrong.

The ballroom attracted some of the most popular musicians and singers, including Guy Lombardo, Tommy Dorsey, Frank Sinatra, Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, the Ink Spots, Harry James, and Louis Armstrong.

The park was a popular venue for school events.

The park was a popular venue for school events.

The casino and dance floor. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

The casino and dance floor. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

The park’s miniature train. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

The park’s miniature train. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

A woman celebrated Labor Day in 1939 by aquaplaning near the park on a slab of wood. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library Star-Telegram Collection.)

A woman celebrated Labor Day in 1939 by aquaplaning near the park on a slab of wood. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library Star-Telegram Collection.)

In 1961 the park sponsored Miss Casino Beach and Mr. Casino Beach contests. The house orchestra was conducted by Guy Woodward.

In 1961 the park sponsored Miss Casino Beach and Mr. Casino Beach contests. The house orchestra was conducted by Guy Woodward.

But as time passed, so did people’s passion for big band music. Rock and roll and television had captured the public imagination. Too, by 1972 the cavernous wooden ballroom was deteriorating.

The city, which owned the land and leased it to the casino operator, wanted the ballroom to be closed.

Nonetheless, that year Dan Blocker (“Hoss Cartwright” of the TV series Bonanza, made an offer to buy the casino to keep it open.

Blocker died two weeks later.

In January 1973 Hearne Wrecking Company, which had demolished so many Quality Hill mansions and other Fort Worth’s landmarks, began tearing down the ballroom, beginning with the roof.

In January 1973 Hearne Wrecking Company, which had demolished so many Quality Hill mansions and other Fort Worth’s landmarks, began tearing down the ballroom, beginning with the roof.

Entertainment columnist Jack Gordon later recalled that on January 31, as the wrecking crew wrecked, longtime Casino Park operator Jerry Starnes arranged for the workers to spare temporarily a patch of the dance floor measuring five by five feet. Starnes had brought a portable tape recorder. Gordon wrote: “Starnes and his partner danced over the dust and debris to Glenn Miller’s Sunset Serenade in honor of the thousands of couples who had come before them.”

Casino Park operated nominally into the 1980s but without the ballroom, the boardwalk, Big Boy, the miniature railroad, the Thriller, and the other attractions that for almost a half-century had made Casino Park “the playground of the Southwest.”

Hi, Mike. I recently discovered hometownbyhandlebar and am hooked. Do you have any idea what happened to plans for Casino Beach Revitalization that were featured in Fort Worth Magazine (July 2014)?

Thanks, Paul. I looked into that briefly when I was researching the history. As far as I can tell, those plans are on hold if not dead. Here is a website: .