Christmas of 1914 was anything but merry for the Ewell Pope family of Houston.

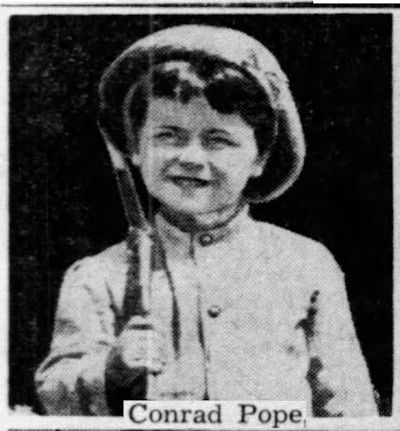

On Christmas Eve, Conrad, the only child of Ewell and Lena Pope, developed a sore throat and fever. He began to cough. His neck began to swell.

On Christmas Eve, Conrad, the only child of Ewell and Lena Pope, developed a sore throat and fever. He began to cough. His neck began to swell.

A doctor was consulted. Worst fears were confirmed: diphtheria, a bacterial disease so deadly that it was called “the strangling angel of children.”

By Christmas morning Conrad was too sick to play with the special gift that Santa Claus had brought him: a toy tool chest. Conrad asked that the toy tools be given to some less-fortunate children he had seen in an alley.

Conrad, only seven, seemed fatalistic.

The Star-Telegram’s C. L. Richhart later wrote that Conrad “kept calling his parents to the bedside, telling them he was going away, that he was going to heaven.”

“He told his mother not to worry, not to cry, that many other boys and girls were waiting for her to come and help them. He said he was going to a mansion in the sky, a mansion built for all good children. Conrad’s parents at first told themselves their little boy was delirious with fever. But he kept repeating the words until he died on December 28, 1914.”

Conrad’s dying wish was that his mother “build a big mansion and fill it up with children.”

Richhart wrote: “Conrad’s words left a deep imprint on his mother. She’s never believed anything else but that the Lord was speaking to her through her little son.”

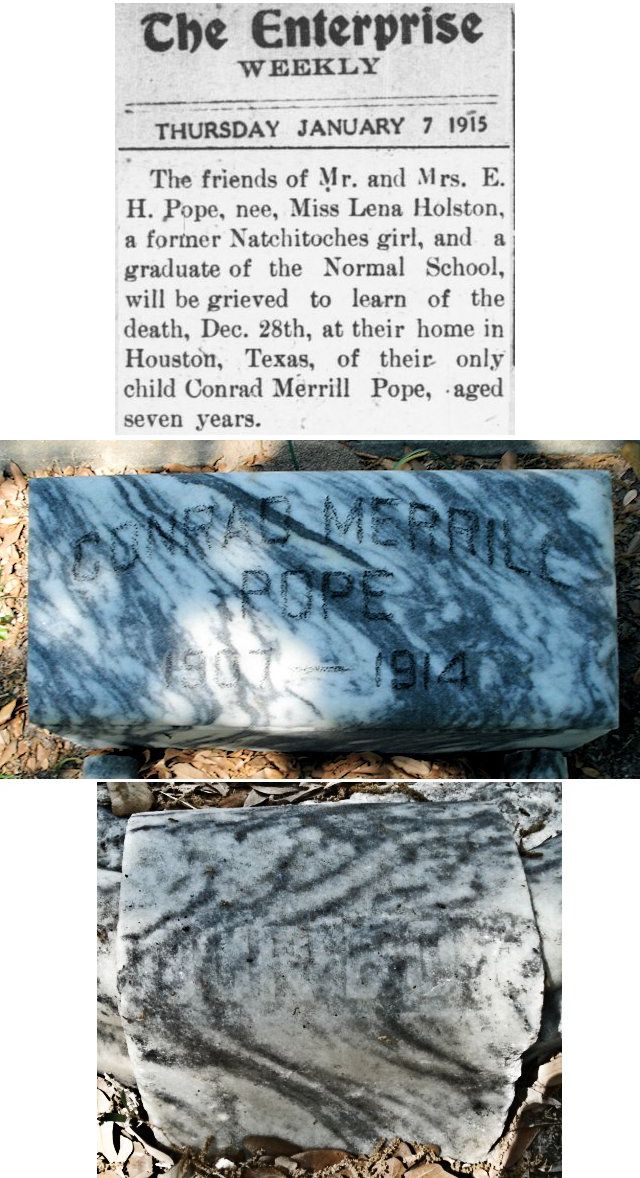

Conrad Merrill Pope is buried in Houston. At the foot of his grave are embossed the words “Our Boy.”

Conrad Merrill Pope is buried in Houston. At the foot of his grave are embossed the words “Our Boy.”

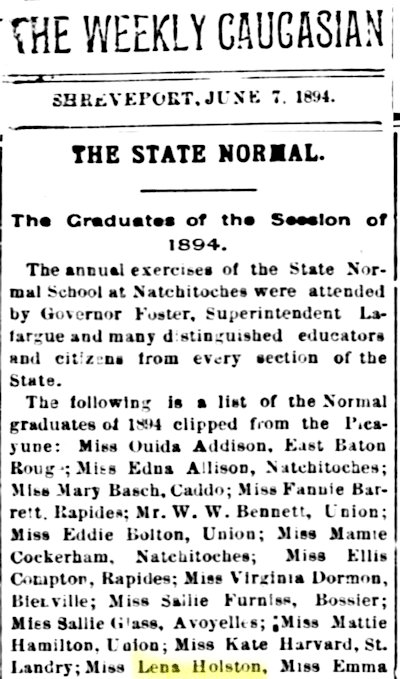

Conrad’s mother was born “Lena Holston” in Natchitoches, Louisiana in 1881. She graduated from Louisiana Normal School in 1894.

Conrad’s mother was born “Lena Holston” in Natchitoches, Louisiana in 1881. She graduated from Louisiana Normal School in 1894.

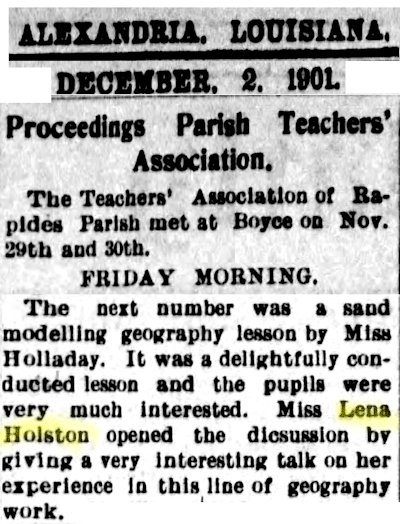

She taught in public schools of Alexandria for five years. During that time she met Ewell Hicks Pope, a bookkeeper for a lumber company. They were married in 1904 and honeymooned at the St. Louis World’s Fair.

She taught in public schools of Alexandria for five years. During that time she met Ewell Hicks Pope, a bookkeeper for a lumber company. They were married in 1904 and honeymooned at the St. Louis World’s Fair.

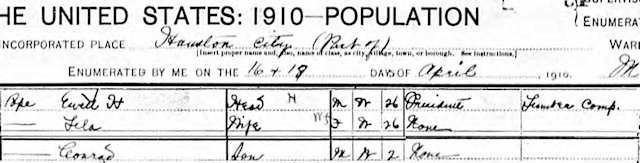

Ewell’s career in the lumber industry soon took the couple to Houston, where son Conrad was born in 1907.

Ewell’s career in the lumber industry soon took the couple to Houston, where son Conrad was born in 1907.

Later, after Conrad’s death, Ewell’s business moved the couple to Dallas to live. There Mrs. Pope started a Sunday school class for newsboys.

After Ewell’s business moved the couple to an east Texas sawmill town, Mrs. Pope continued her social work, organing a community program for children.

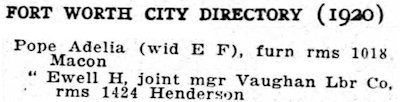

In 1919 the Popes moved to Fort Worth, where Ewell co-managed a lumber company.

In 1919 the Popes moved to Fort Worth, where Ewell co-managed a lumber company.

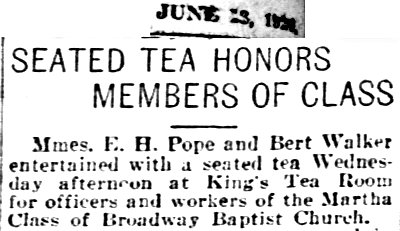

Mrs. Pope joined Broadway Baptist Church and was asked to teach the Martha Class—a women’s Sunday School class. The charity project of the Marthas was helping needy children. For example, the Marthas sewed clothing and blankets for Texas storm victims and for children of Buckner Orphans’ Home in Dallas. They placed deserted children in private homes. At any given time a half-dozen homeless children might be living in the basement of the church while waiting to be placed in homes.

Mrs. Pope joined Broadway Baptist Church and was asked to teach the Martha Class—a women’s Sunday School class. The charity project of the Marthas was helping needy children. For example, the Marthas sewed clothing and blankets for Texas storm victims and for children of Buckner Orphans’ Home in Dallas. They placed deserted children in private homes. At any given time a half-dozen homeless children might be living in the basement of the church while waiting to be placed in homes.

Then came the Marthas’ biggest challenge.

In Paris, Texas on New Year’s Eve 1929 six siblings aged three to fourteen were abandoned by their parents. The oldest child, Harold Massey, had been helped before by Mrs. Pope and the other Marthas. So, he shepherded his five siblings onto a cattle car bound for Fort Worth. The six children arrived downtown at night as revelers celebrated the new year. Amid the merrymaking Harold begged a nickel from a stranger and telephoned Mrs. Pope for help.

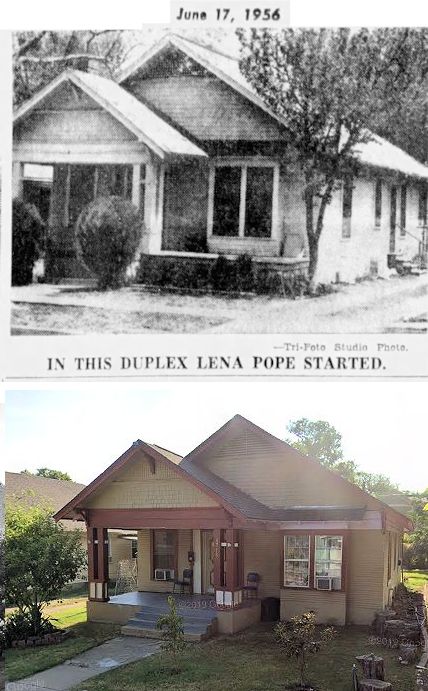

Mrs. Pope worked quickly. She took in the six children, and she and the Martha Class president, Mrs. R. D. Evans, and the class treasurer, Mrs. William Rigg, rented one-half of a duplex for the children at 1715 Washington Avenue in Fairmount. The children slept on mattresses that Mrs. Pope brought from her own home.

With that humble, hurried beginning, Lena Pope Home opened on New Year’s Day 1930. Within a week the impromptu orphanage was housing twelve children and two adults.

Just as a child quickly outgrows shoes and clothing, the orphanage outgrew its housing, occupying three different houses in its first year. All three are still standing.

This is the duplex at 1715 Washington Avenue.

This is the duplex at 1715 Washington Avenue.

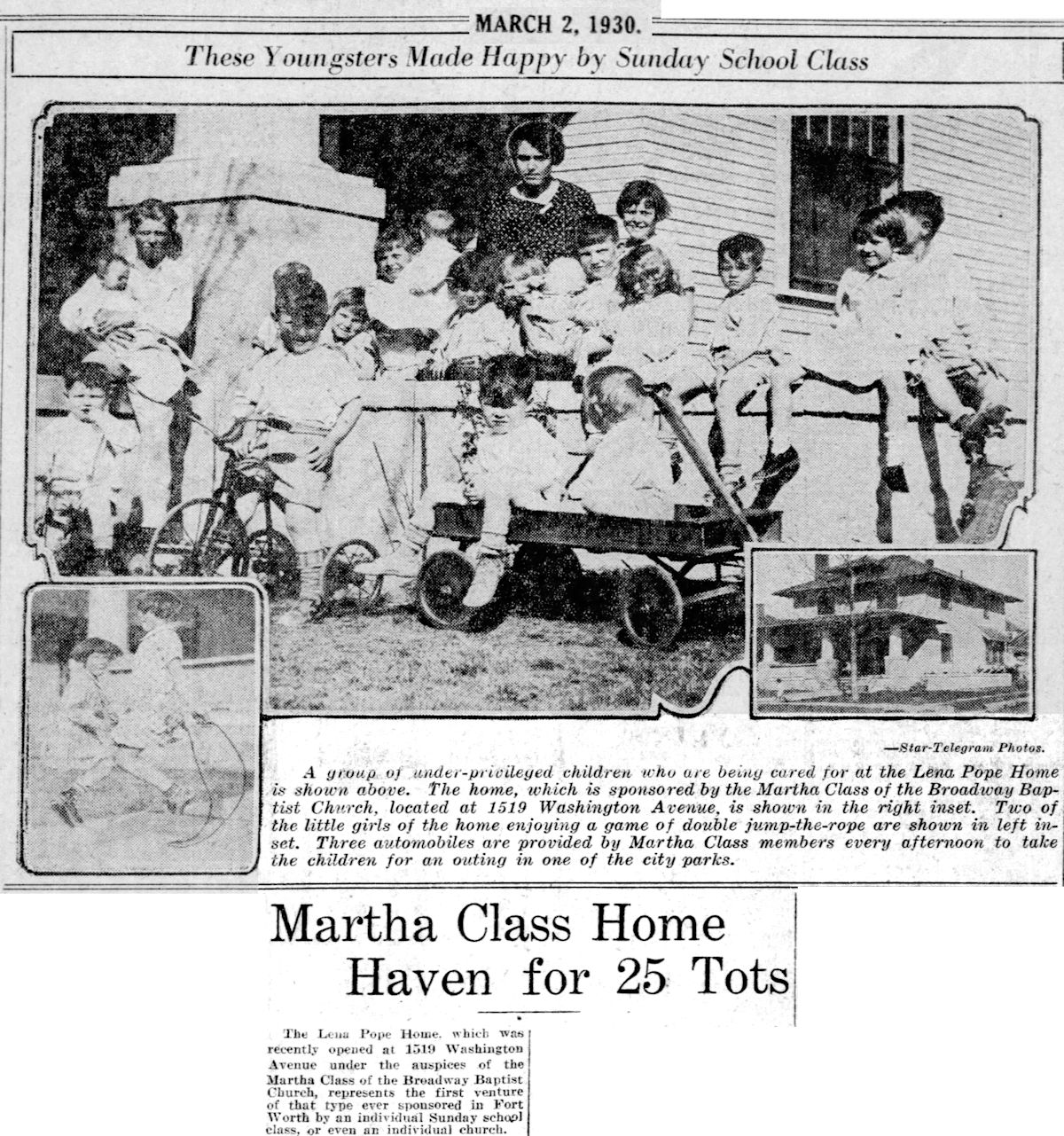

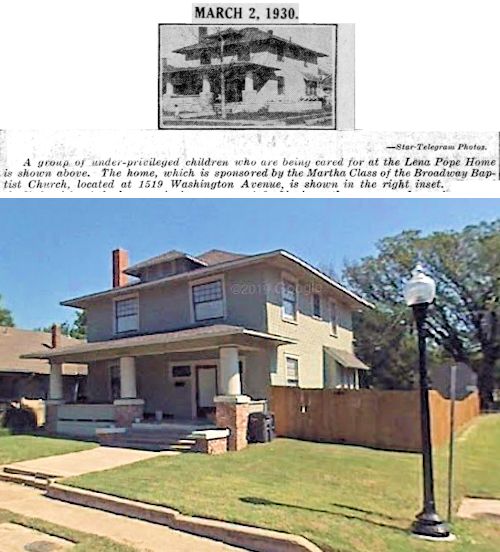

By March the orphanage had moved to a larger house at 1519 Washington.

By March the orphanage had moved to a larger house at 1519 Washington.

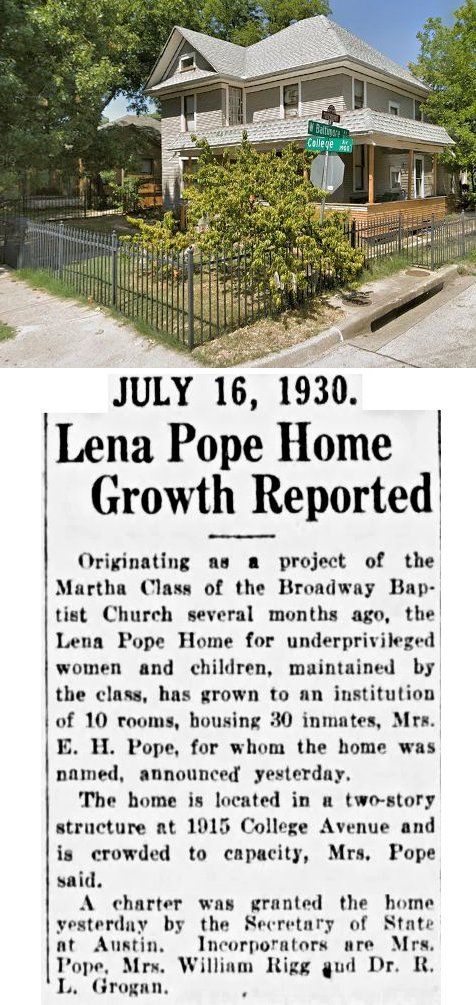

By July the orphanage had relocated to a larger house at 1915 College Avenue but already was “crowded to capacity.” The Lena Pope Home had just been chartered.

By July the orphanage had relocated to a larger house at 1915 College Avenue but already was “crowded to capacity.” The Lena Pope Home had just been chartered.

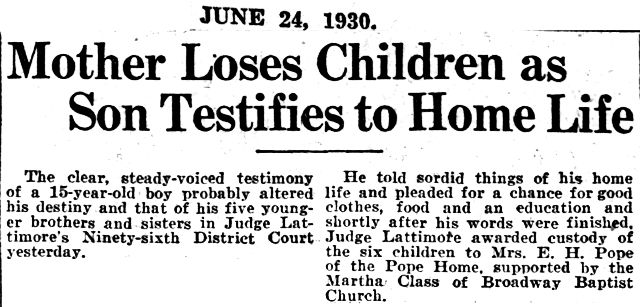

Also in 1930 Mrs. Pope and her home were awarded custody of the Massey children.

Also in 1930 Mrs. Pope and her home were awarded custody of the Massey children.

From the beginning the Lena Pope Home operated on three tenets established by Mrs. Pope:

- Families should not be broken up by adoption.

- Children should never be put in uniform.

- Children should attend public schools and church.

With the orphanage’s rapidly increasing population, Mrs. Pope began soliciting help from the community. C. A. Lupton, whose wife had helped found the Martha Class, agreed to take care of the groceries for a year. A nurse resigned her job at a hospital to work at the orphanage.

Over the years the angel of the orphans would have supporting angels besides C. A. Lupton: civic leaders who supported her work, among them Amon Carter, Leo Potishman, William Monnig, W. E. Connell, and J. Lee Johnson Jr.

The orphanage would be a favorite charity of employees of the “bomber plant,” the Jaycees, and First National Bank, which for years hosted the children of the home at a Christmas party complete with gifts and Santa Claus.

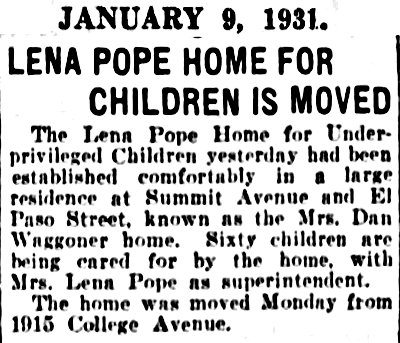

In 1931 the Lena Pope Home moved into its first mansion: the fourteen-room former home of Mrs. Sicily Ann Halsell Waggoner (1842-1928), widow of cattleman Dan Waggoner, at 1418 El Paso Street on Quality Hill.

In 1931 the Lena Pope Home moved into its first mansion: the fourteen-room former home of Mrs. Sicily Ann Halsell Waggoner (1842-1928), widow of cattleman Dan Waggoner, at 1418 El Paso Street on Quality Hill.

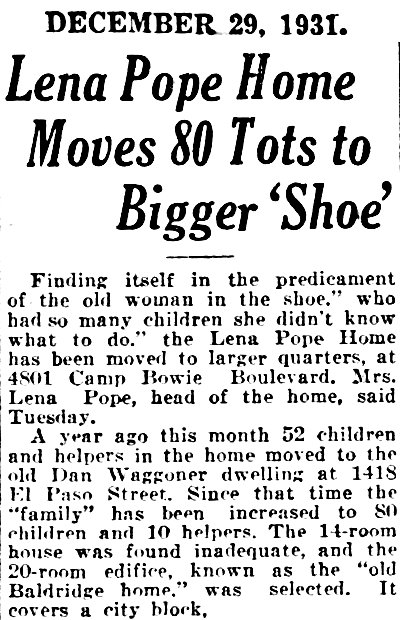

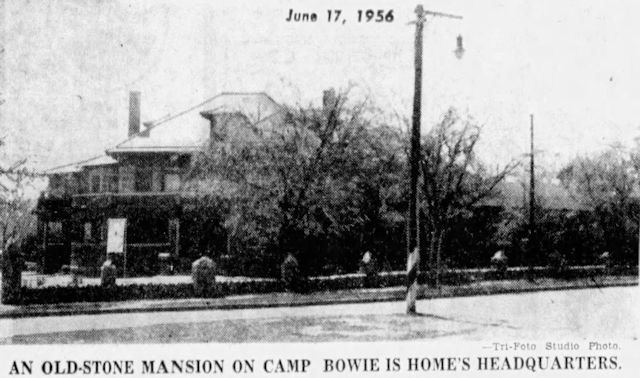

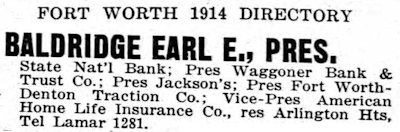

But by the end of the year the orphanage again had outgrown its space. In December the orphanage moved to its second mansion: the twenty-room former home of capitalist Earl E. Baldridge at 4801 Camp Bowie Boulevard (at Sanguinet Street).

But by the end of the year the orphanage again had outgrown its space. In December the orphanage moved to its second mansion: the twenty-room former home of capitalist Earl E. Baldridge at 4801 Camp Bowie Boulevard (at Sanguinet Street).

Masonry contractor and future mayor William Bryce had built the mansion of granite left over from construction of the courthouse in 1895.

Masonry contractor and future mayor William Bryce had built the mansion of granite left over from construction of the courthouse in 1895.

Earl E. Baldridge had committed suicide on the grounds of his mansion in 1915.

Earl E. Baldridge had committed suicide on the grounds of his mansion in 1915.

The grounds of the Baldridge estate covered a city block.

The orphanage remodeled the mansion to accommodate children and staff. But soon the orphanage—you guessed it—needed more space. Dormitories were built of sandstone donated by a farmer; Tarrant County Commissioners Court donated use of gravel trucks to haul building materials; boys of the home dug foundations for the new dormitories. Men standing in Salvation Army breadlines during the Great Depression were recruited to help build the dormitories, a dining room, and an infirmary. Mrs. Pope used her Packard to shuttle unemployed men from the Union Mission to the mansion grounds to break rocks for a stone wall.

(The Baldridge mansion was demolished in 1959 to make way for commercial development.)

The mission of an orphanage is helping others. And first the Great Depression and then World War II placed many families in need of help by the Lena Pope home. During the depression some parents lost their jobs and were unable to care for their children. During the war some parents who joined the war effort were unable to care for their children.

As for the home itself, more than 130 members of its “family” served in the war.

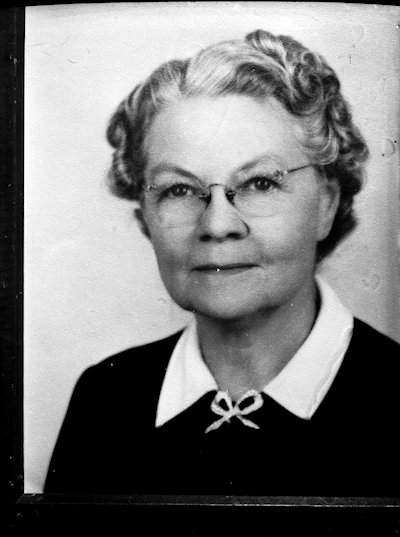

Lena Pope and “family” in 1947. (Photos from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

Lena Pope and “family” in 1947. (Photos from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

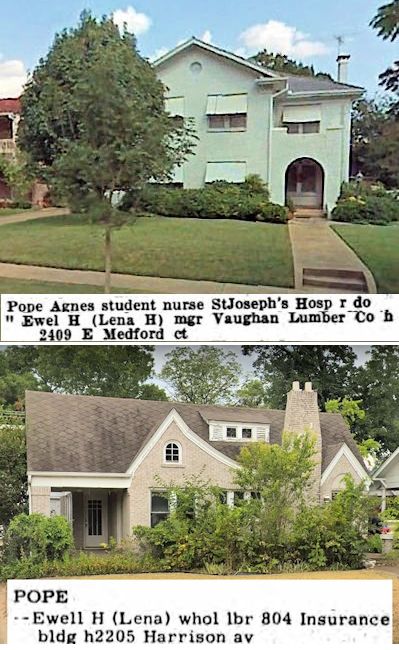

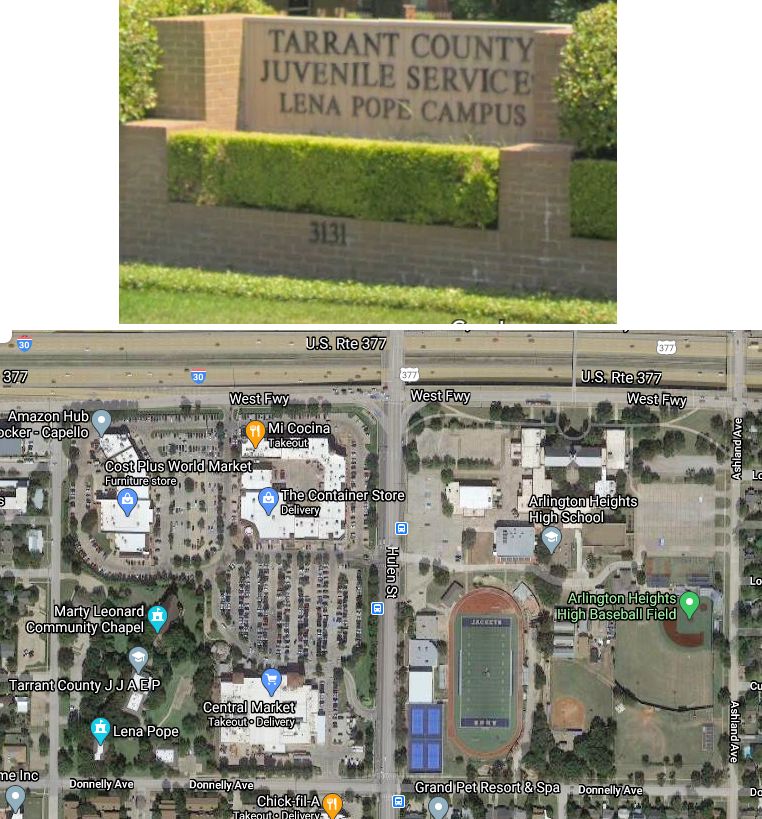

By 1947 the Lena Pope Home had helped five thousand children—and once again needed more space. With the help of Amon Carter the orphanage secured ten city blocks west of Arlington Heights High School on which to build a new home. Architect for the new orphanage, which could house five hundred children “without crowding,” was Joseph Pelich.

By 1947 the Lena Pope Home had helped five thousand children—and once again needed more space. With the help of Amon Carter the orphanage secured ten city blocks west of Arlington Heights High School on which to build a new home. Architect for the new orphanage, which could house five hundred children “without crowding,” was Joseph Pelich.

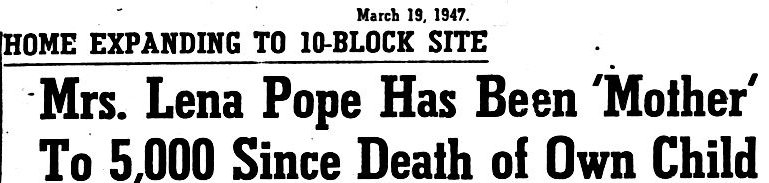

Mrs. Pope had two homes, of course: the orphanage and her residence. At least three homes of Ewell and Lena Pope still stand. Two of them are at 2205 Harrison Avenue in Mistletoe Heights and 2409 Medford Court East in Park Hill.

Mrs. Pope had two homes, of course: the orphanage and her residence. At least three homes of Ewell and Lena Pope still stand. Two of them are at 2205 Harrison Avenue in Mistletoe Heights and 2409 Medford Court East in Park Hill.

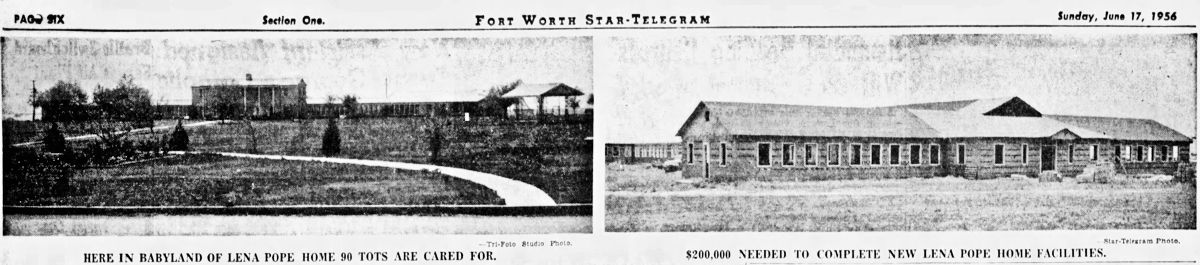

By 1956 much of the new campus on the West Side was completed, but the orphanage was still raising money to complete its new home.

By 1956 much of the new campus on the West Side was completed, but the orphanage was still raising money to complete its new home.

On a hill on the West Side, Lena Pope and her children moved into their third and final mansion. (Photo from UNT Libraries Special Collections.)

On a hill on the West Side, Lena Pope and her children moved into their third and final mansion. (Photo from UNT Libraries Special Collections.)

Over the years Lena Pope’s good deeds were recognized locally and even nationally. She was named Fort Worth’s “Outstanding Citizen” in 1946 and was the first woman to receive the Fort Worth Exchange Club’s Golden Deeds Award in 1947. In 1958 she was honored on the TV program Queen for a Day. In 1967 she was named “Texas Baptist Mother of the Year.”

But she was proudest of being known as “Mom” to thousands of orphans.

Lena Pope retired from management of the home in 1962 upon the death of her husband but remained an influential member of the board of directors.

By the time her autobiography, Hand on My Shoulder, was published in 1966 her orphanage had housed more than ten thousand children ranging from babies to teenagers.

As adults those children spoke fondly of their time at the home:

“We were one big family,” Bob Keller of New Mexico told the Star-Telegram in 2000. Keller lived at the home from 1932 to 1942. “We didn’t know we were orphans. We were known and we were loved.”

Donnie McDaniel of Fort Worth, who lived at the home from 1933 until 1940, recalled that “Mrs. Pope was like an angel to us. Everyone at the home treated us so well.”

And Dan Jaquess of Bluffdale said, “If I hadn’t been at the Pope home, I don’t know where I would have ended up. I might have been in jail or somewhere. This place saved a lot of lives.”

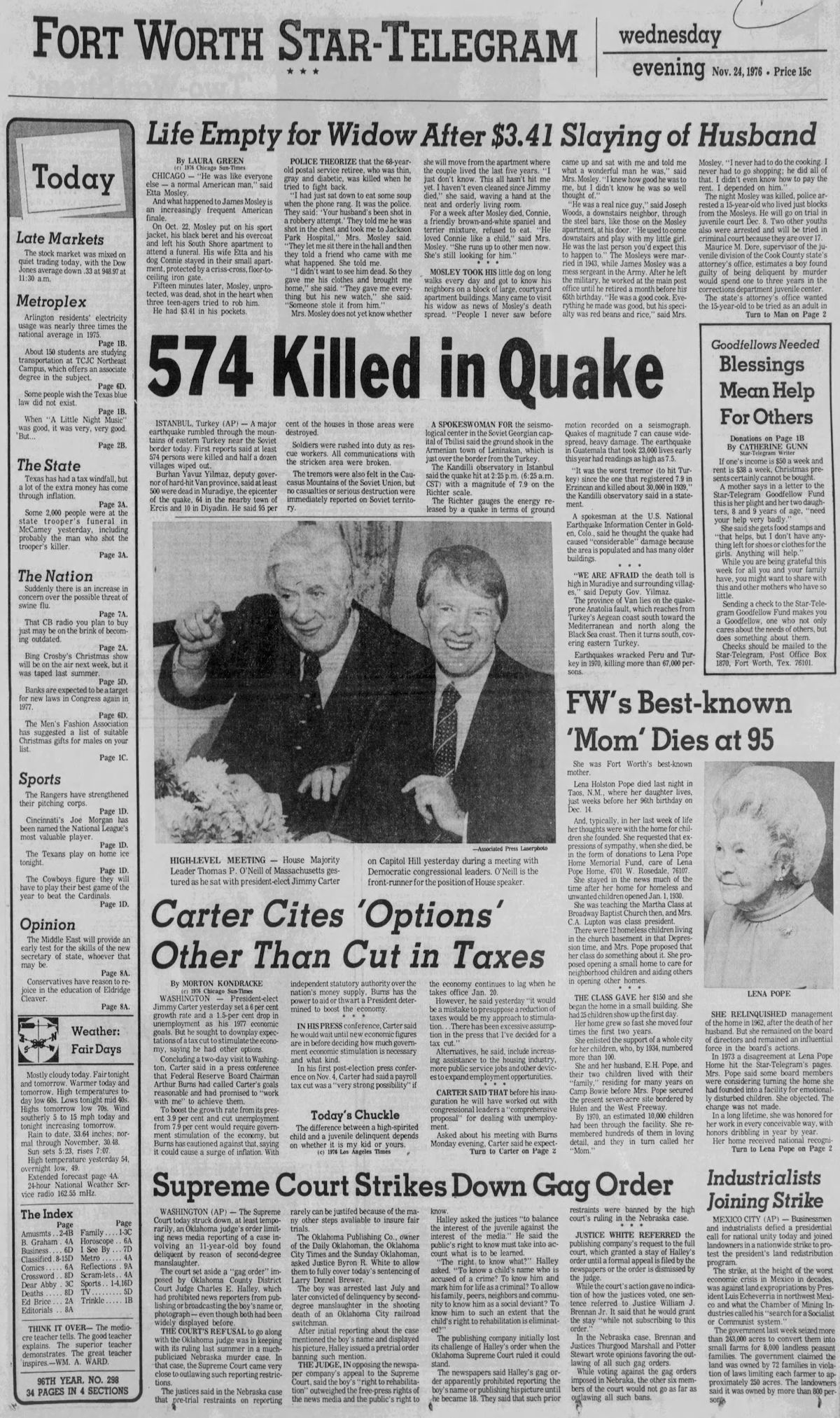

Lena Pope, who devoted her life to fulfilling her dying son’s wish that she “build a big mansion and fill it up with children,” died on November 24, 1976 in Taos, New Mexico. She was ninety-five years old.

Lena Pope, who devoted her life to fulfilling her dying son’s wish that she “build a big mansion and fill it up with children,” died on November 24, 1976 in Taos, New Mexico. She was ninety-five years old.

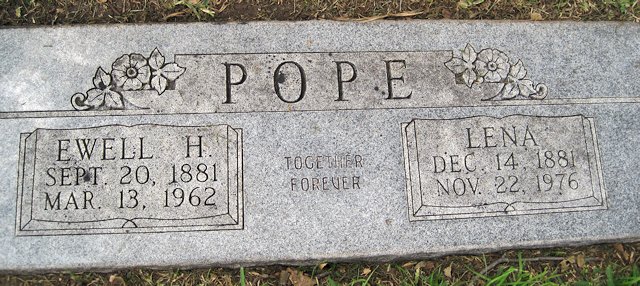

Lena Pope is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Lena Pope is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

In the 1990s the Lena Pope Home leased much of its original West Side campus for commercial development. Now the organization occupies the southwest corner of the campus with the Marty Leonard Community Chapel and Tarrant County’s Juvenile Justice Alternative Education Program. With time the home’s focus has changed. In fact, the organization now calls itself just “Lena Pope” without the “Home” and no longer provides residential and foster care. But 106 years after a son’s dying wish at Christmas, the organization that his mother founded continues to serve children—about four thousand a year—through counseling and substance use services, Project SAFeR (Safety and Family Resiliency), Chapel Hill Academy public charter school, and Lena Pope Early Learning Centers.

In the 1990s the Lena Pope Home leased much of its original West Side campus for commercial development. Now the organization occupies the southwest corner of the campus with the Marty Leonard Community Chapel and Tarrant County’s Juvenile Justice Alternative Education Program. With time the home’s focus has changed. In fact, the organization now calls itself just “Lena Pope” without the “Home” and no longer provides residential and foster care. But 106 years after a son’s dying wish at Christmas, the organization that his mother founded continues to serve children—about four thousand a year—through counseling and substance use services, Project SAFeR (Safety and Family Resiliency), Chapel Hill Academy public charter school, and Lena Pope Early Learning Centers.

Other Cowtown benefactors of orphans:

Edna Gladney

Belle Burchill

Belle and I. Z. T. Morris and the orphan trains

Masonic Home

Posts About Women in Fort Worth History

Great article. My father worked at Lena Pope Home for close to 30 years. This article brought me back to my childhood where I spent many a day and sometimes nights on the LPH campus. What a remarkable lady!

Thank you for visiting the site. Unfortunately the author, Mike Nichols, passed away and we are working on how best to preserve this informative site.

A wonderful article, Mike. Thank you for sharing. I live just three doors down from Mrs. Pope’s former home on Harrison Ave.

Thanks, Charlie. She was one of Cowtown’s angels.

Thank you for sharing the incredible story of Lena Pope to your readers. We are proud of our humble grassroots beginning. We are grateful to those who continue to share our mission with others.

Gratefully,

Cathy R. Sheffield

Chief Advancement Officer

Lena Pope

Thank you, Ms. Sheffield. The Lena Pope story is one of the most inspiring in Fort Worth’s history.