To Fort Worth’s oldtimers, the mosque of 1917 must have seemed like a reincarnation of the palace of 1889.

Certainly the two buildings had a lot in common.

Certainly the two buildings had a lot in common.

For starters:

- Both the Texas Spring Palace and the Moslah Shrine mosque were exotic buildings for their time and place. (The bottom sketch shows that architects of the mosque were E. W. Van Slyke & Clyde Woodruff. Arthur Albert Messer had designed the Spring Palace.)

- Both buildings were made of wood—a lot of wood. That’s because . . .

- Both buildings were huge. The Spring Palace was 375 feet wide with a dome 155 feet high. The mosque covered almost a city block and had four towers that were four stories tall.

Some back story: During the golden era of fraternal lodges, Fort Worth’s Moslah Shrine was a relative late comer. On April 19, 1914 the Star-Telegram announced that the Shrine Temple—a Masonic order—was forming a lodge in Fort Worth.

On July 4 the Moslah Shrine was formally “instituted” in a ceremony at the chamber of commerce auditorium.

Note the cartoon of a panther wearing Shriner regalia.

Fast-forward three years. Another similarity between the Spring Palace and the mosque: Both were built with a “get ’er done” dispatch not possible today.

Quicker’n you can say “feasibility study” or “environmental impact statement,” the Spring Palace was completed in just thirty-one days.

Likewise, the Shriners did not dilly nor did they dally:

On July 11, 1917 the Star-Telegram praised Moslah Shrine’s “proposal” to build a mosque (lodge hall) at Lake Worth.

On September 6 work on the mosque began at Reynolds Point. The land had been part of the ranch of cattleman George Reynolds. The point was renamed “Mosque Point.”

Just ten weeks later, on November 23, the Shriners held a “gay social event” at their new mosque. The Star-Telegram described the mosque as “recently completed,” but in reality work would continue into 1919.

However, by November 1917 enough of the building was finished for the Shriners to stage a banquet and dance. Women wore their ball gowns; men, their Shriner uniforms and regalia. The event also included a ceremony initiating new members of the lodge, including soldiers from recently completed Camp Bowie and undertaker S. D. Shannon and architect Wiley G. Clarkson.

On July 4, 1919 the Moslah Shrine lodge celebrated its fifth anniversary and formally dedicated its mosque. The interior of the building and landscaping of the grounds would soon be completed.

By the time the building was truly finished, its design differed from the architects’ original sketch. Most noticeably, the spires were gone, and the four corner towers were shorter. Nonetheless, the Star-Telegram described the mosque as “magnificent” and “built after the massive temples of the Far East.” (A.A.O.N.M.S. stands for “Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine.”)

A different view of the mosque. (Photo from DeGolyer Library, SMU.)

The Star-Telegram printed a special section about the Shriners in January 1920 but continued to use the architects’ sketch rather than a photograph of the mosque.

The special section included this photo of the first divan (executive council) of the Moslah Shrine.

A month later the Record printed a full page on the Shiners with photos taken at the mosque.

Yes, the Spring Palace and the mosque had a lot in common. But there also were differences between the two buildings.

For starters, the Spring Palace was centrally located at the south end of downtown on the sprawling Texas & Pacific railroad reservation. It was easily reached on foot or by streetcar or automobile. Being located on the railroad reservation and near the Union Depot, it also was subject to the sounds and smells of a bustling railroad town.

The mosque, on the other hand, was located miles from town on a secluded, serene promontory between the lake and a wooded area. The mosque sat on fourteen acres of unincorporated land.

The mosque, with its four towers, was visible for miles and, in return, offered a view for miles. The view was said to be especially enchanting on moonlit nights.

So isolated was Mosque Point in the beginning that a road had to be cut from Nine Mile Bridge Road to the mosque to bring in construction workers and building material.

By 1920 a road would encompass the lake, and the mosque could be reached from Nine Mile Bridge Road or Roberts Cutoff Road.

The mosque was one of the first major attractions at the new lake. The city also opened a “municipal bathing beach” in 1917.

The lake eventually became a major recreational area, of course, especially after Casino Beach opened in 1927. By 1939 the area between Jacksboro Highway and the channel of the West Fork of the Trinity River was dotted with private and commercial camps and areas named for Winfield Scott, Wyatt Hedrick, and Neil P. Anderson. There were camps for Boy Scouts, Panther Boys Club, and Swift packing plant employees.

Amon Carter’s Shady Oak Farm was located east of the mosque.

Indian Oaks housing addition would grow into the city of Lake Worth Village.

Another difference: Whereas the Spring Palace was reachable only by land, the mosque was reachable by land and water: It had its own landing on the lake shore.

The Spring Palace and the mosque also differed in their functions, of course. The city of Fort Worth and the Fort Worth & Denver City Railway had come up with the idea for the Texas Spring Palace exhibition in 1889. The Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad also was a major sponsor. The exhibition was ostensibly a fair intended to promote Texas agricultural products and to attract settlers and investors to the state. But as the host city, Fort Worth naturally shared in the limelight and hoped to grab the panther’s share of glory, immigrants, and capital investment.

The mosque, naturally, was built to be a reflection of its builders and to host Moslah Shrine’s social and fraternal gatherings. The mosque had multiple meeting halls and ballrooms, the largest ballroom accommodating one thousand couples—the largest in the Southwest and eclipsed only by the ballroom at Casino Beach in 1927.

Of course, the Shriners used their mosque primarily for their own events, both formal and informal. In 1928 the Shriners threw a hoedown to honor master Masons, and Fort Worth was home to enough Masons to inspire Leonard’s Department Store to target Masons with a sale on overalls, chambray shirts, bandannas, and gingham dresses.

The Shriners also rented the mosque to outside groups for dances, parties, conventions.

In 1926 the Texas & Pacific railroad rented the mosque to celebrate the jubilee anniversary of the arrival of the first train in town.

The Shriners also staged dances and other entertainments for the general public. The Moslah Shrine Band often performed.

In 1924 the Shriners sold the mosque to the Methodist District. Soon after, the ubiquitous Star-Telegram writer C. L. Richhart reported, one of the speakers at the opening of the Texas Methodist Assembly at the mosque would be Fort Worth attorney Julian C. Hyer (father of actress Martha Hyer). Hyer held the twin titles of “great titan” of the Texas Ku Klux Klan and “exalted cyclops” of the Fort Worth KKK lodge.

Two years later the Shriners repossessed the mosque after the Methodist District became financially stressed.

And lastly, the Spring Palace and the Moslah Shrine mosque had one more similarity: Both were destroyed by fire, the Spring Palace on the night of May 30, 1890, the mosque on the afternoon of January 10, 1929.

The custodian of the mosque in 1929 was Fort Worth police officer John Alsup. Alsup and his wife and son lived across the street. About 5 p.m. on Thursday, January 10 the mosque was occupied by only Alsup, his son, age seven, and the boy’s dog. Father and son were in the basement of the mosque, which contained three gasoline engines “used in the lighting system,” the Star-Telegram later wrote, presumably to power electric generators. The basement also contained several storage tanks of gasoline, three of them of fifty gallons each.

When Alsup started one of the engines, unbeknownst to him, gasoline had leaked from one of the tanks. A spark from the engine caused the gasoline to ignite. As the fire spread, another tank of gasoline exploded. Alsup’s hands were burned. Because of the smoke and fire Alsup could not reach a chemical fire extinguisher on a wall of the basement. When the three fifty-gallon tanks exploded, Alsup and his son fled. The boy went in search of his dog, who was somewhere in the building. Young Alsup found his dog, and only with great difficulty did they grope their way through the smoke to an exit.

When Alsup was free of the inferno he tried to telephone the fire department, but the fire had already burned the mosque’s telephone line. He ran across the street to his home, but that telephone line, too, was burned.

Alsup recrossed the road to the mosque. His car was parked there, the top of it burned by the fire. He drove two miles to a pay phone at Nine Mile Bridge to summon the fire department.

By the time he got back to the mosque its roof was collapsing.

Smoke and flames were visible for miles, and the roads leading to the mosque were soon congested with automobiles of spectators.

Heat from the fire could be felt several hundred feet away.

The fire threatened to spread to neighboring houses. Neighbors carried the contents of one house to safety and formed bucket brigades to keep the fire from nearby houses, including Alsup’s.

The mosque was miles from a fire station. Two companies of firefighters were dispatched, but the mosque burned to the ground in less than an hour. All that remained standing was the mosque’s three-story brick chimney and some stone columns.

(Five months after the mosque burned, Casino Beach burned.)

Here is another difference between the Spring Palace and the mosque:

The Spring Palace had been crowded with hundreds of people when fire broke out there. The mosque was empty except for two people and a dog.

But here is another similarity:

The central figure in each fire was a man who is remembered in history:

Al Hayne and John Alsup.

And yet even within this final similarity there is a final difference.

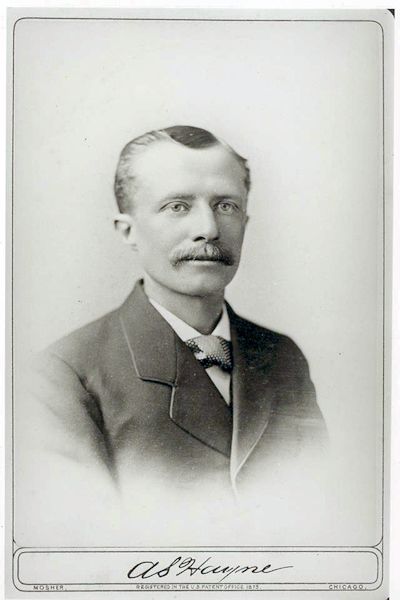

Al Hayne is remembered as a hero for helping people escape the fire. (Photo from retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster.)

Al Hayne is remembered as a hero for helping people escape the fire. (Photo from retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster.)

John Alsup, too, is remembered but not as a hero. There were no panic-stricken people for him to save that day in 1929. He was a man overwhelmed by a sudden conflagration. He could be at best a survivor, not a hero. Rather, John Alsup is remembered as the ex-police officer who a year after the mosque fire was charged with murdering two men whom he had plotted to frame for bank robbery in order to collect a reward.

John Alsup, too, is remembered but not as a hero. There were no panic-stricken people for him to save that day in 1929. He was a man overwhelmed by a sudden conflagration. He could be at best a survivor, not a hero. Rather, John Alsup is remembered as the ex-police officer who a year after the mosque fire was charged with murdering two men whom he had plotted to frame for bank robbery in order to collect a reward.

Today two place names are reminders of the palace on Reynolds Point.

And now the rest of the story: Six weeks after the fire Fort Worth Masons and Shriners announced that they would build a new temple on Henderson Street. Architect of the new fortress of fraternity? Wiley G. Clarkson, Shrine initiate of 1917.

And now the rest of the story: Six weeks after the fire Fort Worth Masons and Shriners announced that they would build a new temple on Henderson Street. Architect of the new fortress of fraternity? Wiley G. Clarkson, Shrine initiate of 1917.

Wow. What a lot of great info. My head is a buzz. I’m going to save this so I can read again and probably again. My old brain doesn’t soak it up like it used to but I really enjoyed reading this.

Thanks, Chris. LOL. I am seldom accused of underresearching.