Railroads no longer have the presence in Fort Worth that they did for a century. And streetcars have gone the way of flappers and flivvers.

But reminders—some of them subtle—of the age of railroads and streetcars can be found in all four parts of town. And those reminders can help us answer the question “Why?”

North

Houston Street

For example, see those two parallel lines running down the middle of North Houston Street? Why did a railroad track once run down the middle of that street?

For example, see those two parallel lines running down the middle of North Houston Street? Why did a railroad track once run down the middle of that street?

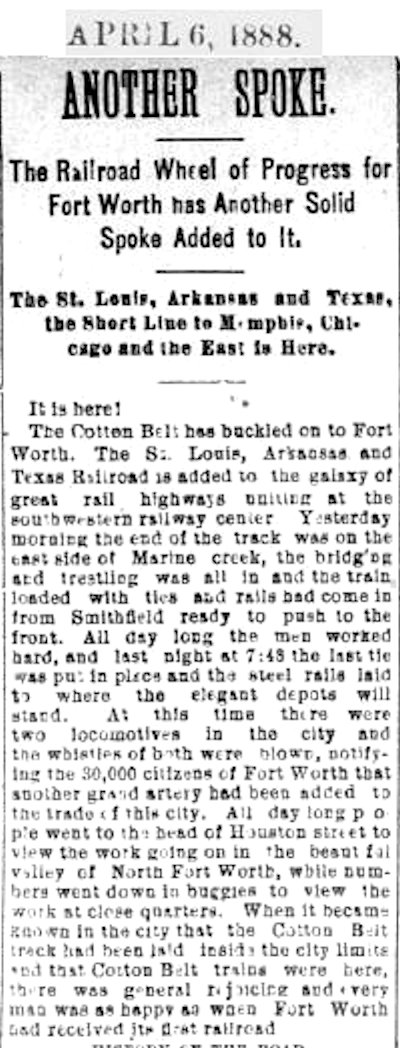

The answer begins in 1888, when the St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas (later “St. Louis-Southwestern,” known as the “Cotton Belt”) railroad began service in Fort Worth.

The answer begins in 1888, when the St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas (later “St. Louis-Southwestern,” known as the “Cotton Belt”) railroad began service in Fort Worth.

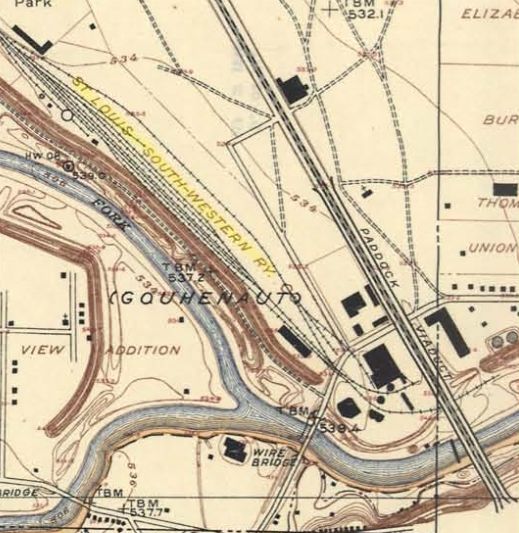

The Cotton Belt’s yard was located just north of the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the Trinity River and west of North Main Street.

The Cotton Belt’s yard was located just north of the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the Trinity River and west of North Main Street.

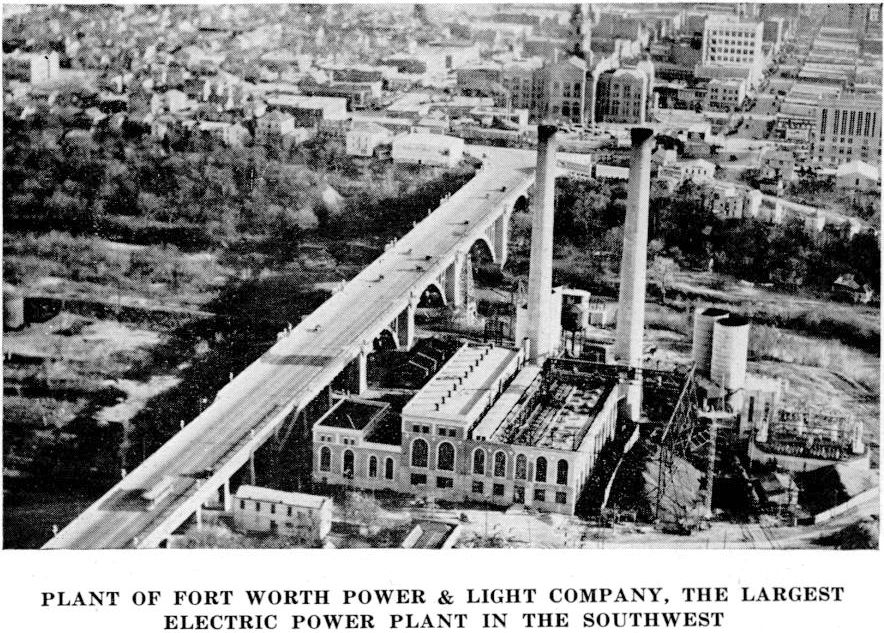

Fast-forward to 1913. The new generating plant of Fort Worth Power & Light Company began operation just east of the Cotton Belt yard. No doubt the proximity of the Cotton Belt tracks—and the Trinity River as a water supply—was a factor in the decision to locate the plant there.

Fast-forward to 1913. The new generating plant of Fort Worth Power & Light Company began operation just east of the Cotton Belt yard. No doubt the proximity of the Cotton Belt tracks—and the Trinity River as a water supply—was a factor in the decision to locate the plant there.

The plant’s boilers burned coal—a lot of coal—to make steam from that river water to turn the turbines to generate electricity. That coal was delivered by railroad cars.

Three Cotton Belt spur tracks ran into the power plant property.

Three Cotton Belt spur tracks ran into the power plant property.

At the plant a crane removed coal from the cars and deposited it in hoppers. Spent coal—in the form of ash—likewise was hauled away in rail cars.

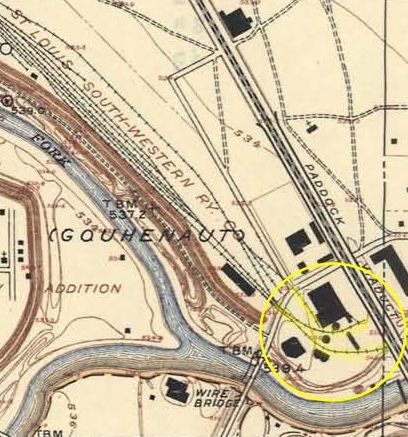

One of those tracks ran smack dab down the middle of North Houston Street. (Spur tracks also ran down the middle of East 7th and West Lancaster streets downtown to serve businesses.)

North Houston Street ran straight into the power plant (remaining buildings circled).

North Houston Street ran straight into the power plant (remaining buildings circled).

South

Katy Lake

Why is Gran Plaza shopping mall located where it is?

Why is Gran Plaza shopping mall located where it is?

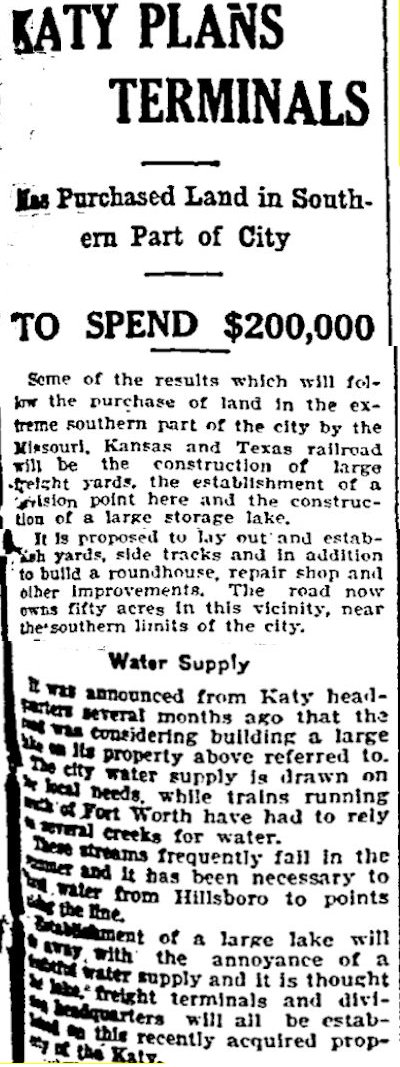

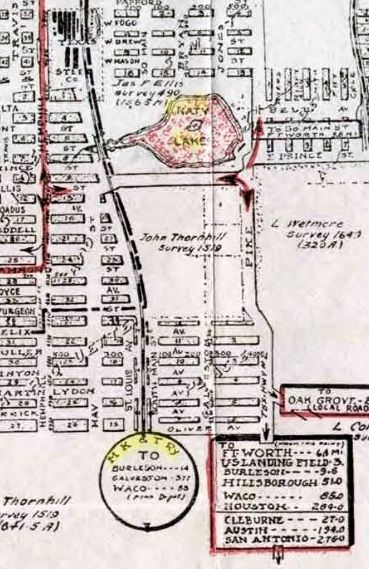

Because in 1907 the Katy railroad, whose track skirts the mall on the west, dammed a creek and impounded a lake there to supply water for its steam locomotives.

Because in 1907 the Katy railroad, whose track skirts the mall on the west, dammed a creek and impounded a lake there to supply water for its steam locomotives.

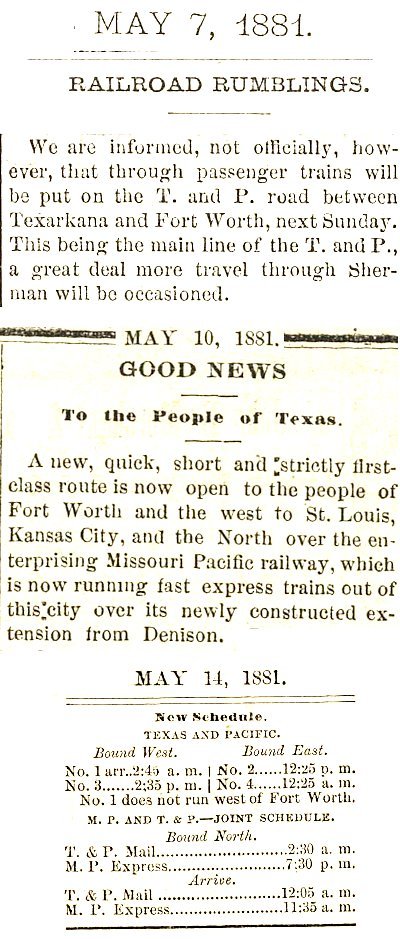

The Missouri Pacific railroad had begun serving Fort Worth in 1881. The railroad later served Fort Worth as the “Missouri, Kansas & Texas” (Katy) railroad. The lake came to be known as “Katy Lake.”

The Missouri Pacific railroad had begun serving Fort Worth in 1881. The railroad later served Fort Worth as the “Missouri, Kansas & Texas” (Katy) railroad. The lake came to be known as “Katy Lake.”

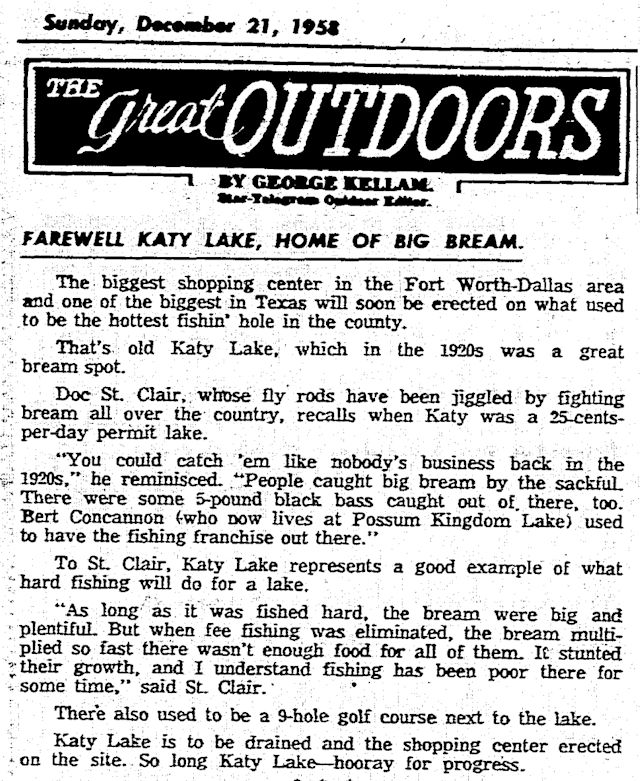

Fast-forward to 1958. The Sears, Roebuck department store company took one gander at the fifty-year-old lake and thought it would be the ideal location for Fort Worth’s first “regional shopping center.”

Fast-forward to 1958. The Sears, Roebuck department store company took one gander at the fifty-year-old lake and thought it would be the ideal location for Fort Worth’s first “regional shopping center.”

Say what?

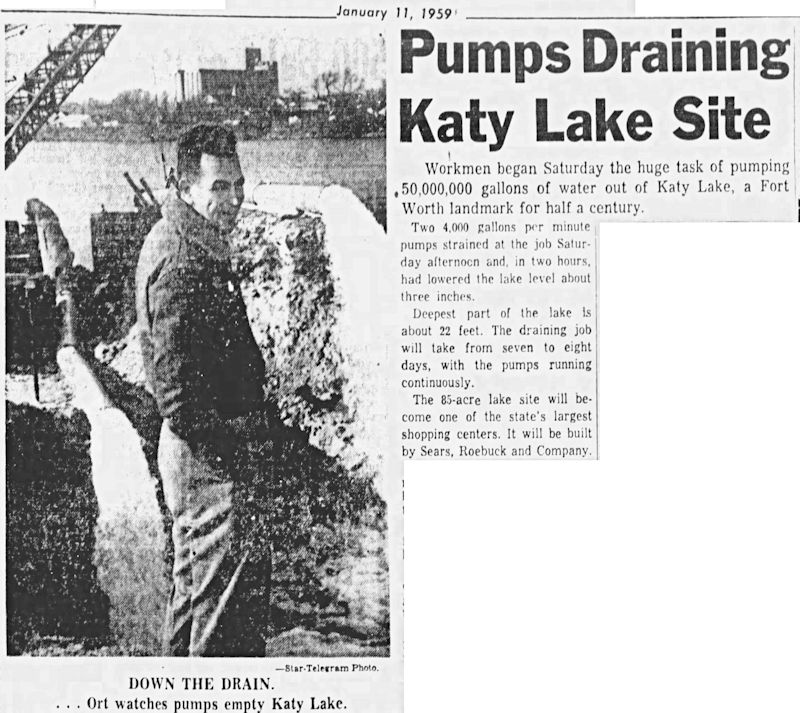

Yes, Sears, Roebuck bought Katy Lake lock, stock, and crappie, and in 1959 the lake was drained of fifty million gallons of water—and its piscine population—and then relieved of eleven million cubic feet of silt (enough to fill TCU’s Amon Carter Stadium four and one-half times).

Yes, Sears, Roebuck bought Katy Lake lock, stock, and crappie, and in 1959 the lake was drained of fifty million gallons of water—and its piscine population—and then relieved of eleven million cubic feet of silt (enough to fill TCU’s Amon Carter Stadium four and one-half times).

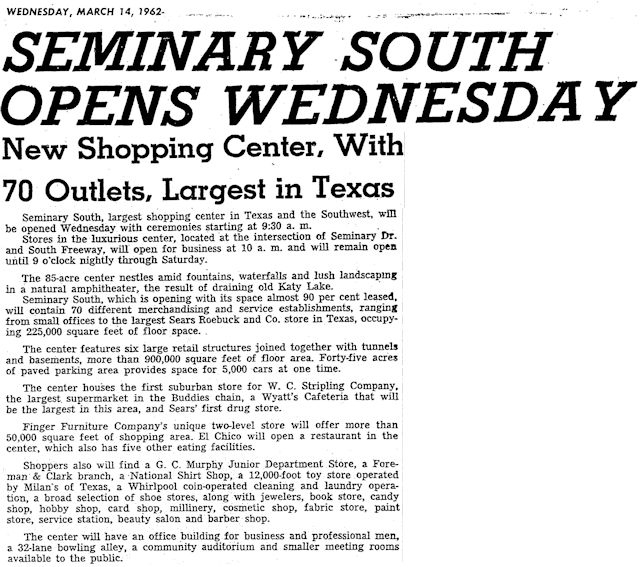

Into that big muddy hole developers poured an eighty-five-acre shopping center with a Sears store as the center’s anchor.

Into that big muddy hole developers poured an eighty-five-acre shopping center with a Sears store as the center’s anchor.

And so in 1962 was born Seminary South (now “Gran Plaza”).

Echo Lake

Why is Echo Lake located where it is?

Why is Echo Lake located where it is?

In 1903 the International & Great Northern railroad began service to Fort Worth. Like the Katy railroad, the I&GN needed water for its steam locomotives. So, it dammed a creek and impounded a twenty-two-acre lake along its track south of town.

In 1903 the International & Great Northern railroad began service to Fort Worth. Like the Katy railroad, the I&GN needed water for its steam locomotives. So, it dammed a creek and impounded a twenty-two-acre lake along its track south of town.

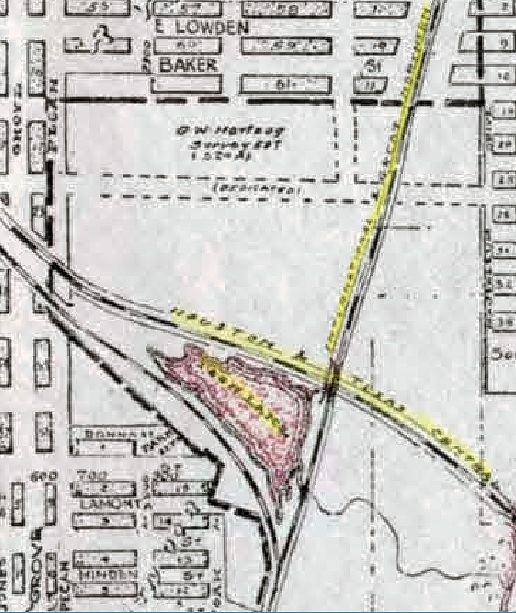

At one time the lake was enclosed by three tracks. The I&GN track forked at the lake, and the track of the Houston & Texas Central railroad skirted on the north. Today Cole Street runs where the west I&GN track ran.

At one time the lake was enclosed by three tracks. The I&GN track forked at the lake, and the track of the Houston & Texas Central railroad skirted on the north. Today Cole Street runs where the west I&GN track ran.

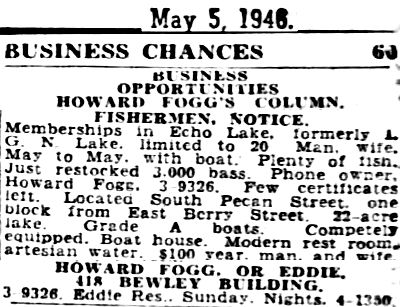

In the 1940s real estate developer Howard Fogg bought the lake and surrounding land and converted them into a members-only sportsman’s park.

In the 1940s real estate developer Howard Fogg bought the lake and surrounding land and converted them into a members-only sportsman’s park.

The city of Fort Worth now owns the property.

The city of Fort Worth now owns the property.

East

Cleburne Interurban

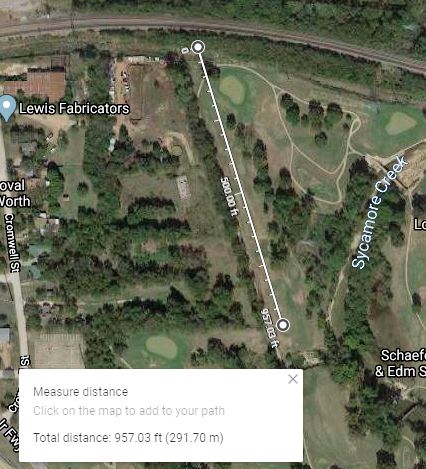

Why is there a 957-foot straight line of trees along the western edge of the old Sycamore golf course?

Why is there a 957-foot straight line of trees along the western edge of the old Sycamore golf course?

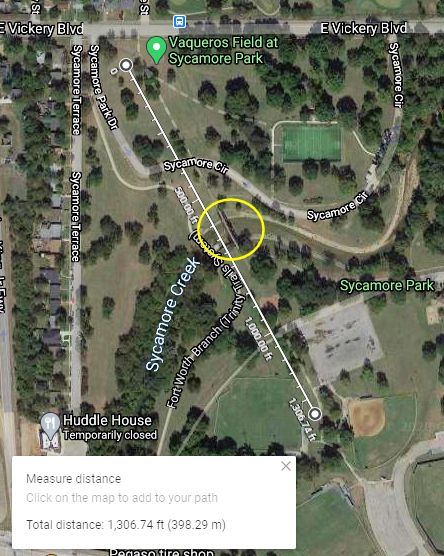

Just south of the golf course in Sycamore Park, why is that sidewalk so straight for 1,300 feet?

Just south of the golf course in Sycamore Park, why is that sidewalk so straight for 1,300 feet?

And what’s the deal with that iron bridge (circled) in the sidewalk over Sycamore Creek?

Why is that bridge so narrow with gaps between its walkway and its sides? You can see the creek below through the gaps.

Why is that bridge so narrow with gaps between its walkway and its sides? You can see the creek below through the gaps.

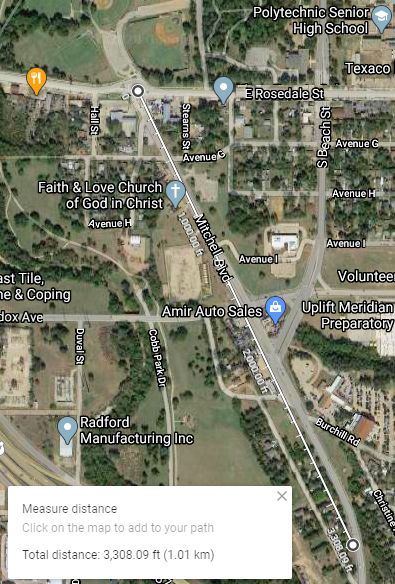

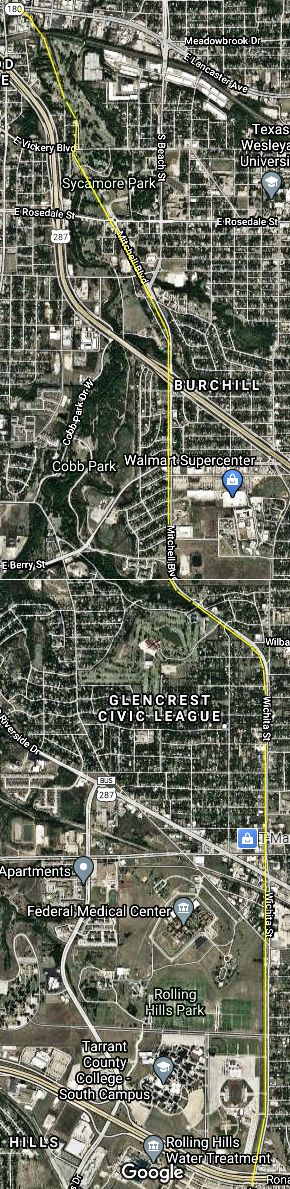

Just south of Sycamore Park, why are the first 3,300 feet of Mitchell Boulevard so straight?

Just south of Sycamore Park, why are the first 3,300 feet of Mitchell Boulevard so straight?

And why does the angle of the first 3,300 feet of Mitchell Boulevard line up perfectly with the angle of the 1,300 feet of sidewalk and bridge (circled) in Sycamore Park?

And why does the angle of the first 3,300 feet of Mitchell Boulevard line up perfectly with the angle of the 1,300 feet of sidewalk and bridge (circled) in Sycamore Park?

Futhermore, why is Wichita Street so straight? It runs 4.8 miles from its junction with Mitchell Boulevard in southeast Fort Worth to Enon Avenue in Everman with only a slight bend.

Futhermore, why is Wichita Street so straight? It runs 4.8 miles from its junction with Mitchell Boulevard in southeast Fort Worth to Enon Avenue in Everman with only a slight bend.

The answer: trolley tracks.

On September 1, 1912 the Fort Worth Southern Traction Company began providing interurban service to Cleburne.

On September 1, 1912 the Fort Worth Southern Traction Company began providing interurban service to Cleburne.

The track to Cleburne branched off the Dallas interurban track at East Lancaster and Grafton streets just east of today’s Riverside Drive, passed under the Texas & Pacific tracks, and ran southeast along the western edge of what in 1932 would become Sycamore golf course.

The track to Cleburne branched off the Dallas interurban track at East Lancaster and Grafton streets just east of today’s Riverside Drive, passed under the Texas & Pacific tracks, and ran southeast along the western edge of what in 1932 would become Sycamore golf course.

The Cleburne interurban right-of-way formed the property line between homes on the west and the golf course on the east. Years after the Cleburne interurban stopped running in 1931, trees grew up (or where planted) along the straight roadbed that served as the property line between the homes and the golf course.

From that straight line along today’s golf course, the interurban track ran southeast to Sycamore Street, south on Sycamore Street into Sycamore Park, and again southeast, crossing the creek on the narrow bridge. After the interurban closed, the track through the park was replaced by a sidewalk, and the track on the bridge was replaced by a concrete walkway: The trolley bridge became a pedestrian bridge. But an imperfect one: There are gaps between the walkway (where the rails had been) and each side of the bridge. So, cables were strung along each side of the walkway to keep pedestrians from falling into the gaps!

Leaving Sycamore Park, the track ran southeast—at the same angle as the sidewalk— along today’s Mitchell Boulevard.

Mitchell Boulevard first appears on a city map in 1939. It was laid out on the roadbed of the Cleburne interurban after the line stopped operating.

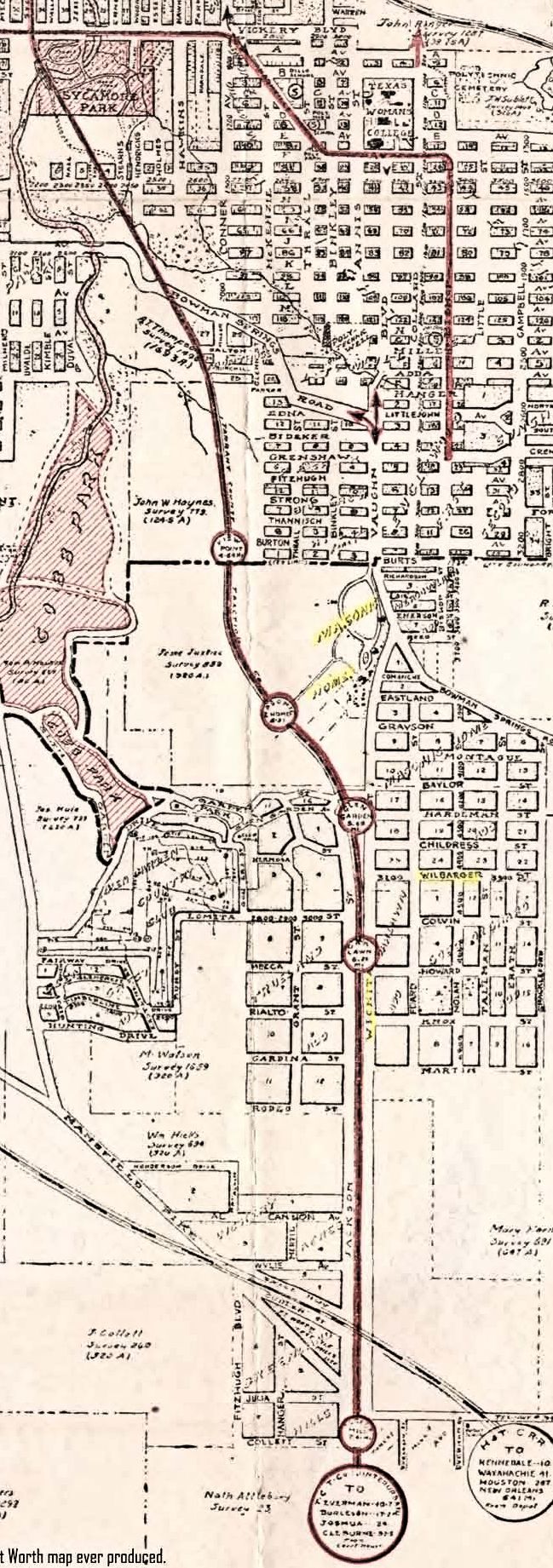

This 1925 map shows that the track skirted Masonic Home (still outside the city limits in 1925) and, after reaching Wichita Street at about the Wilbarger Street intersection, ran due south along Wichita Street toward Everman, Burleson, Joshua, and Cleburne. The trains made only five stops in Fort Worth.

This 1925 map shows that the track skirted Masonic Home (still outside the city limits in 1925) and, after reaching Wichita Street at about the Wilbarger Street intersection, ran due south along Wichita Street toward Everman, Burleson, Joshua, and Cleburne. The trains made only five stops in Fort Worth.

The track ran through mostly open country. The eastern city limit in 1912 was Sycamore Creek. The southern city limit was Biddison Street. After leaving Fort Worth the interurban passed through only one town—Everman—before entering Johnson County.

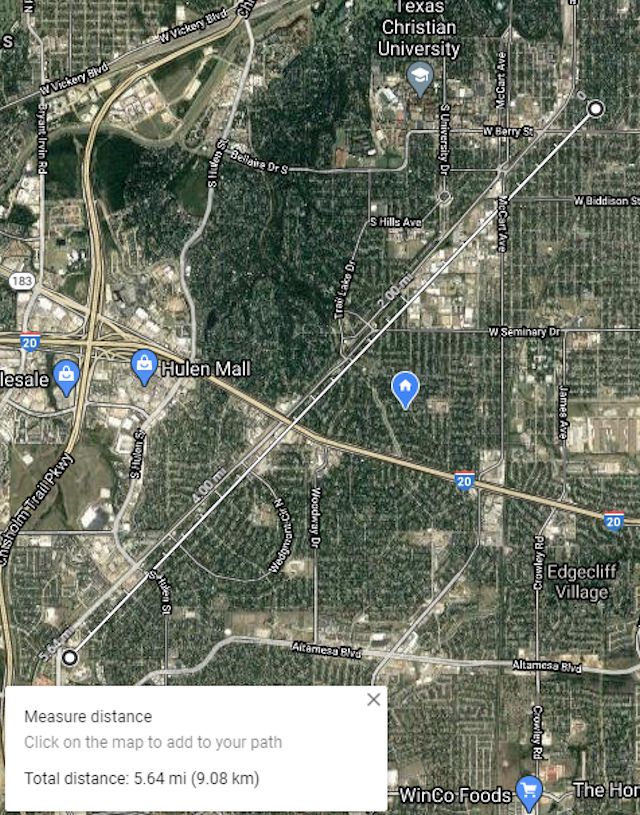

Here is the route of the Cleburne interurban track from Lancaster Avenue past Sycamore golf course, down Sycamore Street, through Sycamore Park, along Mitchell Boulevard to Wichita Street and south along Wichita Street toward Everman.

Here is the route of the Cleburne interurban track from Lancaster Avenue past Sycamore golf course, down Sycamore Street, through Sycamore Park, along Mitchell Boulevard to Wichita Street and south along Wichita Street toward Everman.

A 1920 map shows Wichita Street running south only as far as Mansfield Highway, but a 1930 map shows Wichita Street running south past Mansfield Highway into Forest Hill with the Cleburne interurban line running beside the street. I suspect that the extension of Wichita Street south past Mansfield Highway was laid out along the right-of-way of the interurban line to Cleburne before the line closed.

In Everman a stretch of interurban elevated roadbed and concrete abutments of an interurban bridge over a creek can still be found about sixty-five feet west of Wichita Street near Clyde Pittman Park.

In Everman a stretch of interurban elevated roadbed and concrete abutments of an interurban bridge over a creek can still be found about sixty-five feet west of Wichita Street near Clyde Pittman Park.

Power Lines

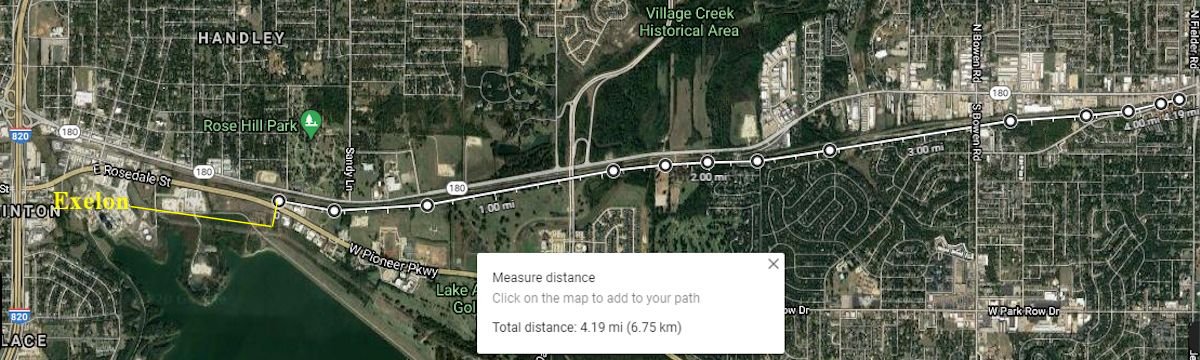

Why do power lines from the Exelon generating plant in Handley run close to and parallel with the Texas & Pacific railroad track and, to a lesser extent, East Lancaster Avenue/West Division Street/Highway 180 in east Fort Worth and west Arlington? The power lines run west from the plant to the 7300 block of East Lancaster and then run north across West Pioneer Parkway (Spur 303) toward Rose Hill Cemetery and then run east, shadowing the railroad track for four miles to Fielder Road in Arlington.

Why do power lines from the Exelon generating plant in Handley run close to and parallel with the Texas & Pacific railroad track and, to a lesser extent, East Lancaster Avenue/West Division Street/Highway 180 in east Fort Worth and west Arlington? The power lines run west from the plant to the 7300 block of East Lancaster and then run north across West Pioneer Parkway (Spur 303) toward Rose Hill Cemetery and then run east, shadowing the railroad track for four miles to Fielder Road in Arlington.

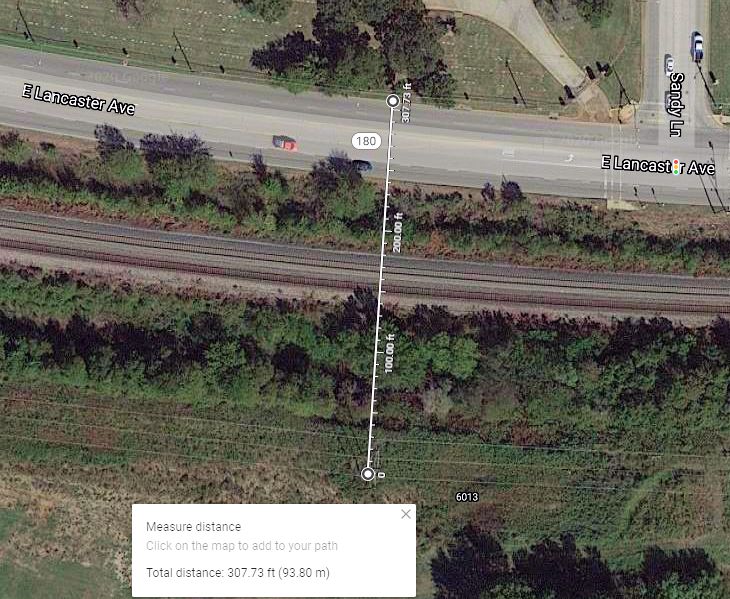

The power lines, railroad tracks, and street run in a corridor that in places is only three hundred feet wide.

The power lines, railroad tracks, and street run in a corridor that in places is only three hundred feet wide.

We can trace the corridor’s history to 1876, when the Texas & Pacific railroad laid track there from Dallas to Fort Worth.

We can trace the corridor’s history to 1876, when the Texas & Pacific railroad laid track there from Dallas to Fort Worth.

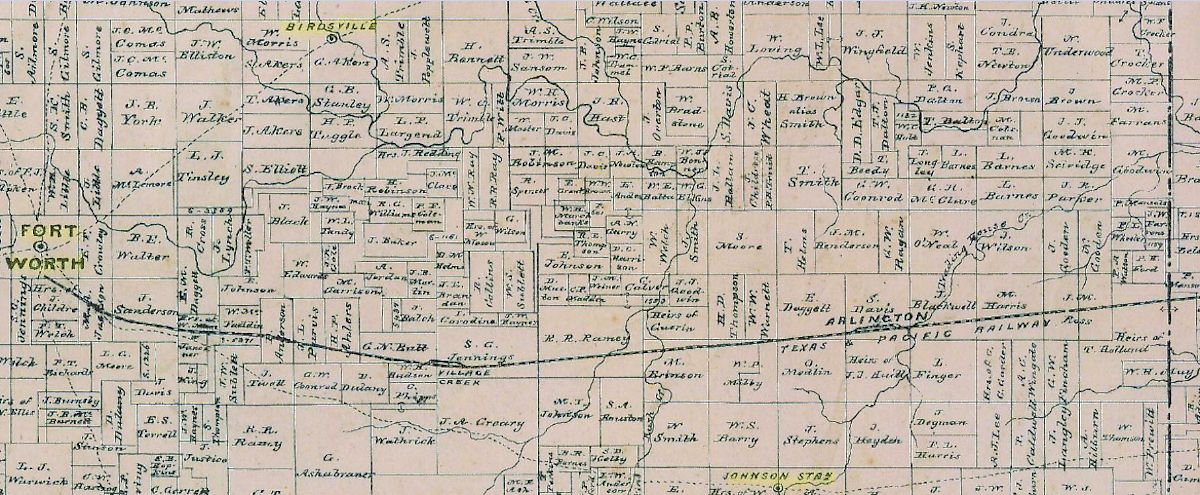

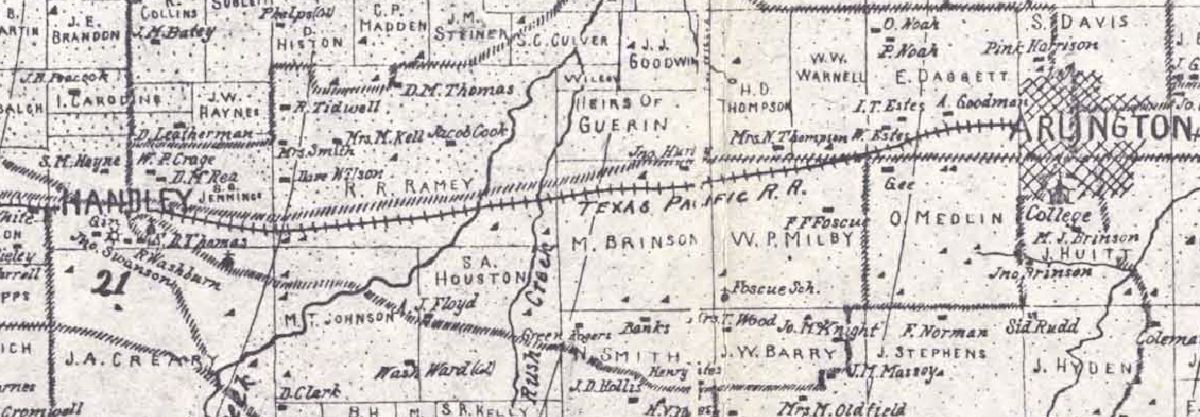

This map of the late 1870s shows wagon roads (dashed lines) connecting Fort Worth and Birdville and Fort Worth and Johnson Station and on into Dallas County but no wagon road along the railroad track.

Fast-forward to 1895. This map shows a wagon road (hashed line) closely shadowing the Texas & Pacific track, especially between Handley and Rush Creek. That wagon road grew into the Dallas Pike, which became the Bankhead Highway/Highway U.S. 180/East Lancaster Avenue/Division Street.

Fast-forward to 1895. This map shows a wagon road (hashed line) closely shadowing the Texas & Pacific track, especially between Handley and Rush Creek. That wagon road grew into the Dallas Pike, which became the Bankhead Highway/Highway U.S. 180/East Lancaster Avenue/Division Street.

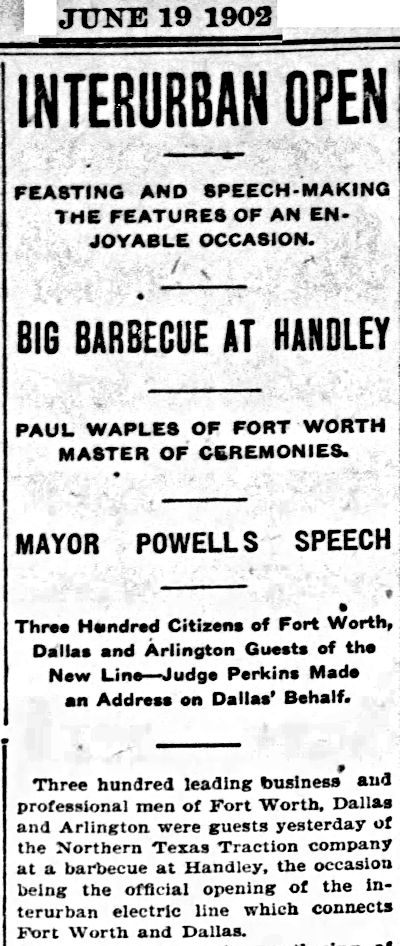

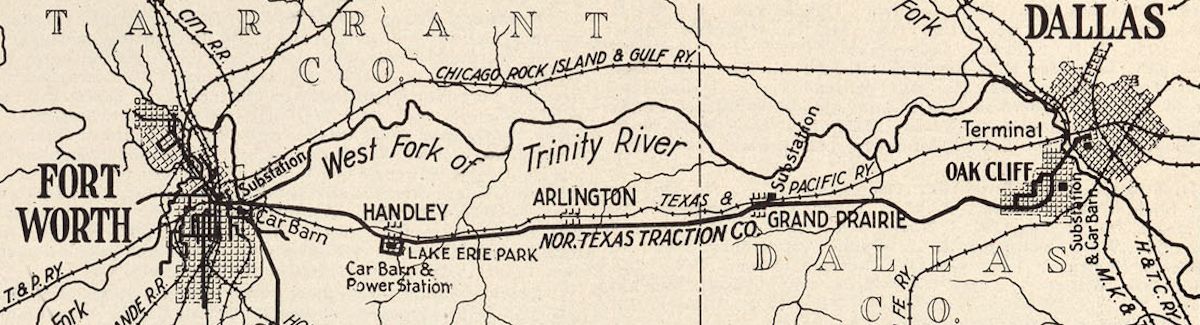

Fast-forward to 1902. Northern Texas Traction Company began operating an electric interurban train service between Fort Worth and Dallas. Owners of the company chose the path of least resistance when they selected a route for the track—the track ran on the Texas & Pacific right-of-way for much of the way, especially between Handley and Arlington. Over the interurban track ran an electric wire that supplied power to each train.

Fast-forward to 1902. Northern Texas Traction Company began operating an electric interurban train service between Fort Worth and Dallas. Owners of the company chose the path of least resistance when they selected a route for the track—the track ran on the Texas & Pacific right-of-way for much of the way, especially between Handley and Arlington. Over the interurban track ran an electric wire that supplied power to each train.

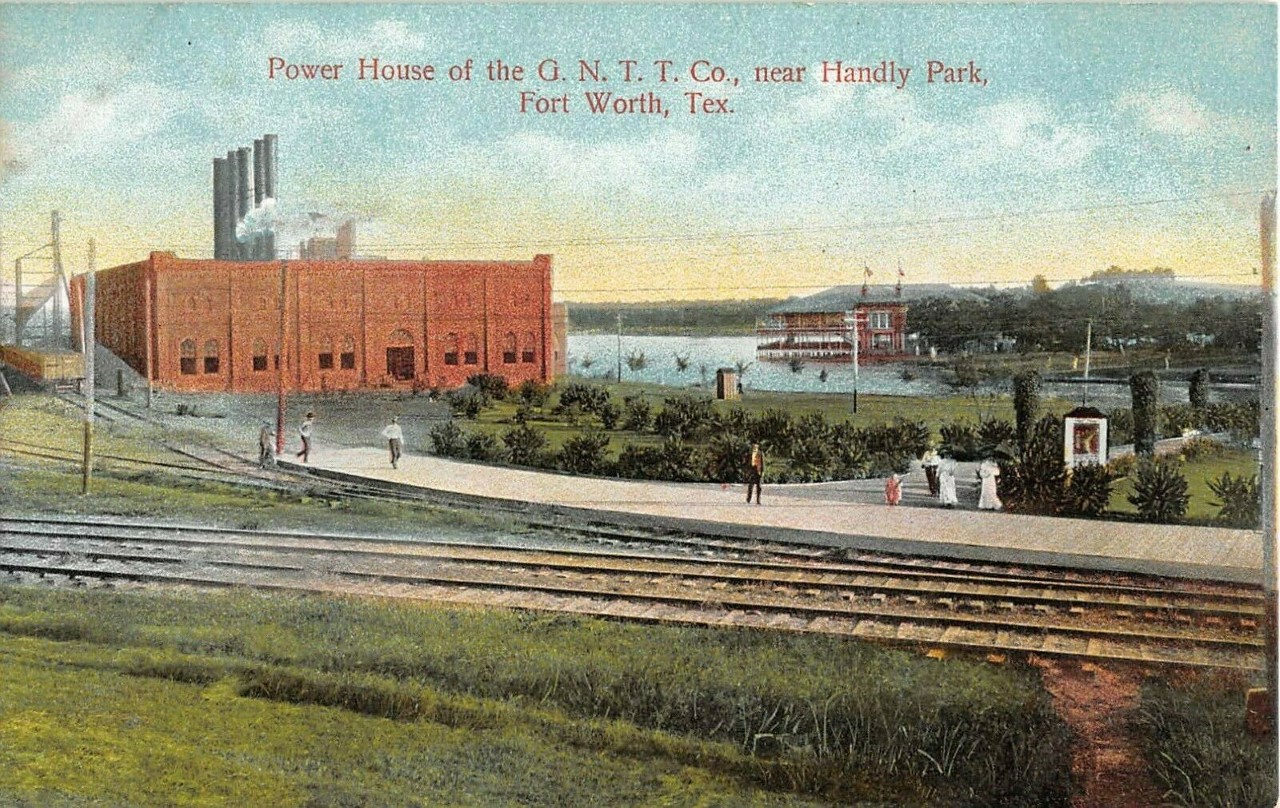

That power came from the NTTC generating plant in Handley. The company dammed a creek to impound a lake—Lake Erie—to provide water for the plant’s boilers to create steam to turn the turbines to generate electricity. NTTC also built a trolley park at the lake to encourage ridership on the interurban.

That power came from the NTTC generating plant in Handley. The company dammed a creek to impound a lake—Lake Erie—to provide water for the plant’s boilers to create steam to turn the turbines to generate electricity. NTTC also built a trolley park at the lake to encourage ridership on the interurban.

Fast-forward to 1929. Texas Electric Service Company was chartered and took over Fort Worth Power & Light Company. Meanwhile the interurban was losing ridership to buses and automobiles.

Fast-forward to 1929. Texas Electric Service Company was chartered and took over Fort Worth Power & Light Company. Meanwhile the interurban was losing ridership to buses and automobiles.

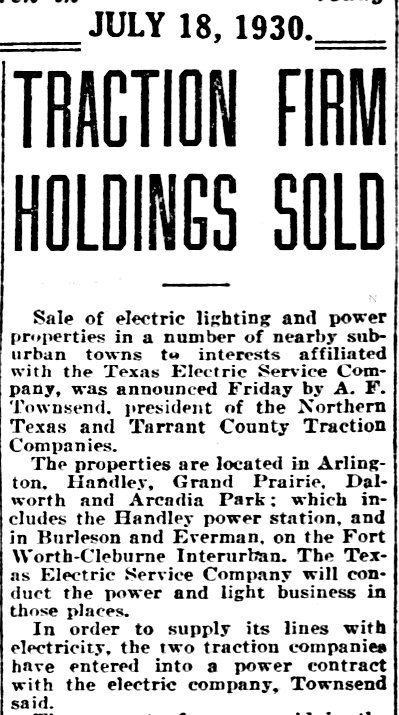

In fact, in 1930 Northern Texas and Tarrant County Traction Companies, which then owned the interurban line to Dallas and the interurban line to Cleburne, sold its power plant in Handley and substations elsewhere on the two lines to TESCO. TESCO agreed to continue to provide electricity for the two interurban lines, but the Cleburne line closed in 1931 and the Dallas line in 1934.

In fact, in 1930 Northern Texas and Tarrant County Traction Companies, which then owned the interurban line to Dallas and the interurban line to Cleburne, sold its power plant in Handley and substations elsewhere on the two lines to TESCO. TESCO agreed to continue to provide electricity for the two interurban lines, but the Cleburne line closed in 1931 and the Dallas line in 1934.

The interurban power plant evolved into the TESCO Handley power plant we remember (with its big Reddy Kilowatt sign), and TESCO used the interurban right-of-way for its power lines east to Arlington.

When Arlington Lake was impounded in 1957, Lake Erie was swallowed, becoming just a cove on the northwest shore of the new lake.

Texas Electric Service Company morphed into TXU. In 2002 TXU sold its Handley plant to Exelon.

Exelon continues to use the interurban right-of-way for its power lines between the plant and west Arlington.

This photo shows the interurban/Exelon power line right-of-way east of the former estate of Paul Waples (who was master of ceremonies at the opening of the interurban in 1902) in west Arlington. That water is Rush Creek. And those slabs of concrete on both sides of the creek? Those are foundations for piers of a bridge that carried the interurban tracks over the creek once upon a time.

This photo shows the interurban/Exelon power line right-of-way east of the former estate of Paul Waples (who was master of ceremonies at the opening of the interurban in 1902) in west Arlington. That water is Rush Creek. And those slabs of concrete on both sides of the creek? Those are foundations for piers of a bridge that carried the interurban tracks over the creek once upon a time.

West

Cleburne/Granbury Road

Why is a five-mile section of Cleburne/Granbury Road so straight—from the 2900 block of Cleburne Road just east of Paschal High School to the southwest subcourthouse at 6551 Granbury Road?

Why is a five-mile section of Cleburne/Granbury Road so straight—from the 2900 block of Cleburne Road just east of Paschal High School to the southwest subcourthouse at 6551 Granbury Road?

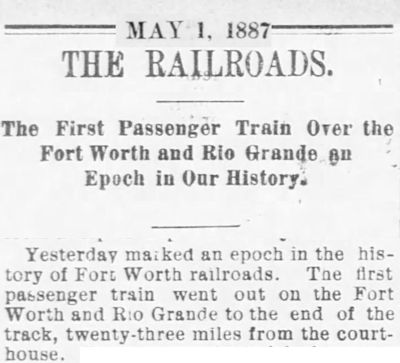

The answer begins in 1887. In that year B. B. Paddock’s tarantula got its ninth leg, and Paddock got his own train set to play with: The Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad began service. Paddock was president of the company.

The answer begins in 1887. In that year B. B. Paddock’s tarantula got its ninth leg, and Paddock got his own train set to play with: The Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad began service. Paddock was president of the company.

Paddock and other Fort Worth civic leaders, with financial backing by the Vanderbilt railroad syndicate, had an ambitious plan for their new railroad: to build a transcontinental route from New York to Fort Worth and across Mexico to the Pacific port of the lyrically named Topolobampo. Laying of track from Fort Worth southwestward began in November 1886. But by May 1887 only twenty-three miles had been laid. By 1891 the track had reached only Brownwood.

And because I know you’ll ask, in 1901 the FW&RG was bought by the Frisco railroad, which sold it in 1937 to the Santa Fe railroad, which in 1994 sold the line to an affiliate of the South Orient railroad. In 1998 South Orient sold the track to Fort Worth & Western railroad, which operates the track to Brown County, where FW&W connects with Burlington Northern Santa Fe track.

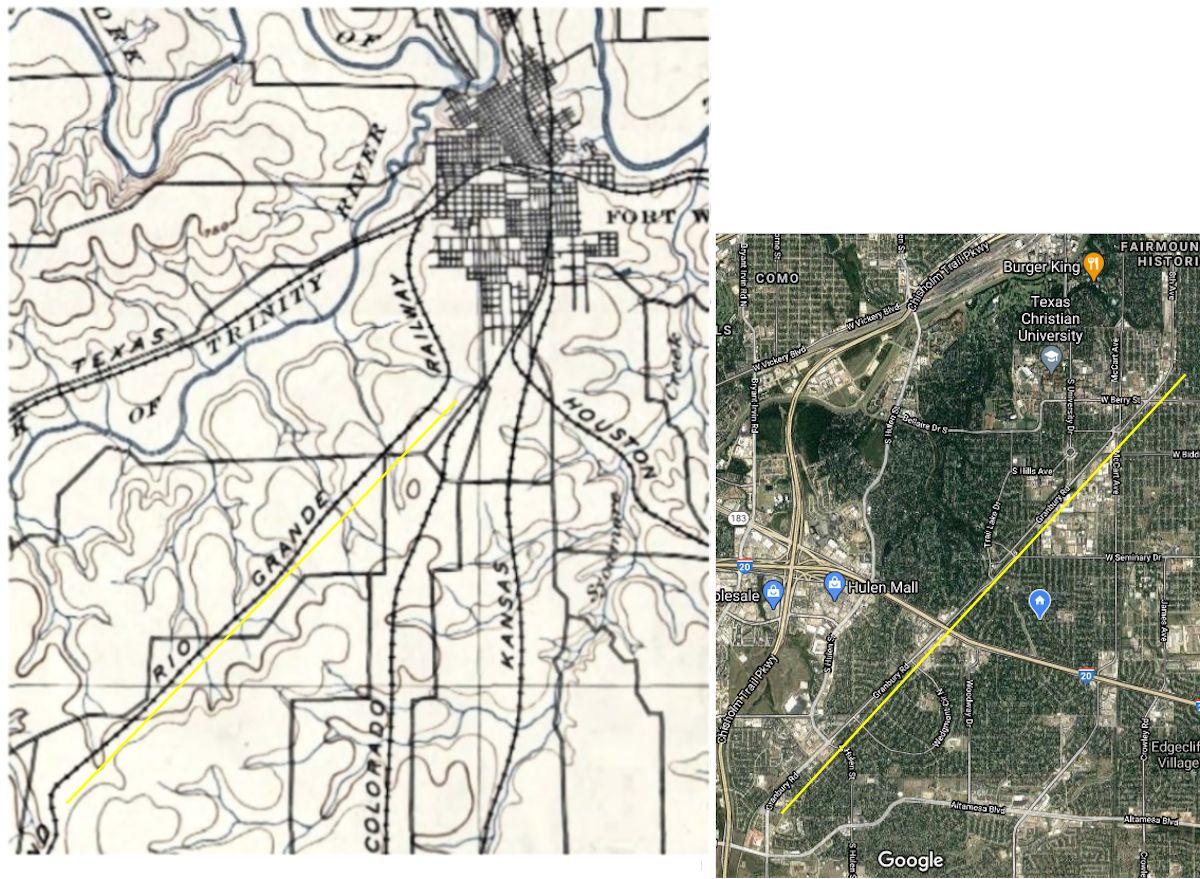

As was a common practice, Granbury Road was laid out along the right-of-way of the Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad track. This 1894 county map and a contemporary satellite photo show how much the world has changed around that five miles of straight track. In 1894 Fort Worth extended south about as far as today’s Berry Street. The stretch of railroad track along today’s Granbury Road ran through open country then. The Fort Worth & Rio Grande could easily acquire right-of-way and lay track in a straight line across undeveloped countryside. (Even in 1952 Granbury Road was still farmland south of where south Loop 820 would be built.)

As was a common practice, Granbury Road was laid out along the right-of-way of the Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad track. This 1894 county map and a contemporary satellite photo show how much the world has changed around that five miles of straight track. In 1894 Fort Worth extended south about as far as today’s Berry Street. The stretch of railroad track along today’s Granbury Road ran through open country then. The Fort Worth & Rio Grande could easily acquire right-of-way and lay track in a straight line across undeveloped countryside. (Even in 1952 Granbury Road was still farmland south of where south Loop 820 would be built.)

Today we could call that five-mile stretch of railroad track and street the “Fort Worth & Rio Granbury.”