They were triplets, born during an extended labor (the youngest and oldest born seven years apart); all three given the same name: City of Fort Worth. The first of the three was the first B-36 bomber ever built. The second was the first combat-ready B-36 ever built. And the third was the last B-36 ever built and the last B-36 ever flown.

These triplets were big babies: born full sized—fuselage length 162 feet, wing span 230 feet—and delivered by Dr. Consolidated-Vultee at the .9-mile-long “maternity hospital” at the bomber plant.

Most babies are a product of love. These babies were a product of war.

Most babies are a product of love. These babies were a product of war.

By December 1944—three years after Pearl Harbor—as B-29s were bombing Tokyo, the U.S. military was testing “new air giants,” including the B-36, “the largest airplane that has been attempted in the country in size.”

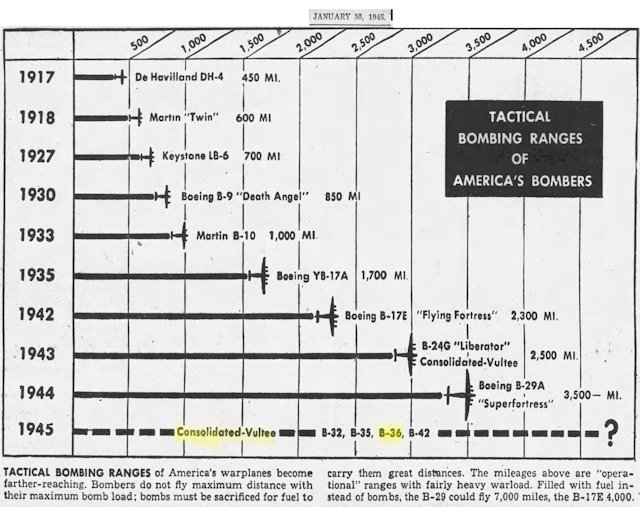

Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft Corporation submitted to the U.S. military the best proposal to build a bomber capable of flying ten thousand miles and carrying five tons of bombs halfway. By January 1945 Fort Worth’s bomber plant was building the B-36, listed on this chart of the tactical bombing ranges of various bombers. The range of the B-36 either was not yet known or was classified.

Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft Corporation submitted to the U.S. military the best proposal to build a bomber capable of flying ten thousand miles and carrying five tons of bombs halfway. By January 1945 Fort Worth’s bomber plant was building the B-36, listed on this chart of the tactical bombing ranges of various bombers. The range of the B-36 either was not yet known or was classified.

For America, World War II ended on September 2, 1945, but development of the B-36 continued, and late in 1945 the range of the B-36 was disclosed: ten thousand miles. Although the war was over, more than 6,500 people were working at the bomber plant as the B-36 made the plant the biggest employer in town.

For America, World War II ended on September 2, 1945, but development of the B-36 continued, and late in 1945 the range of the B-36 was disclosed: ten thousand miles. Although the war was over, more than 6,500 people were working at the bomber plant as the B-36 made the plant the biggest employer in town.

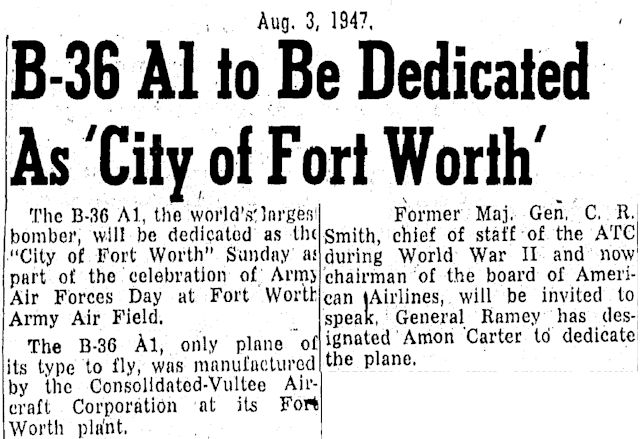

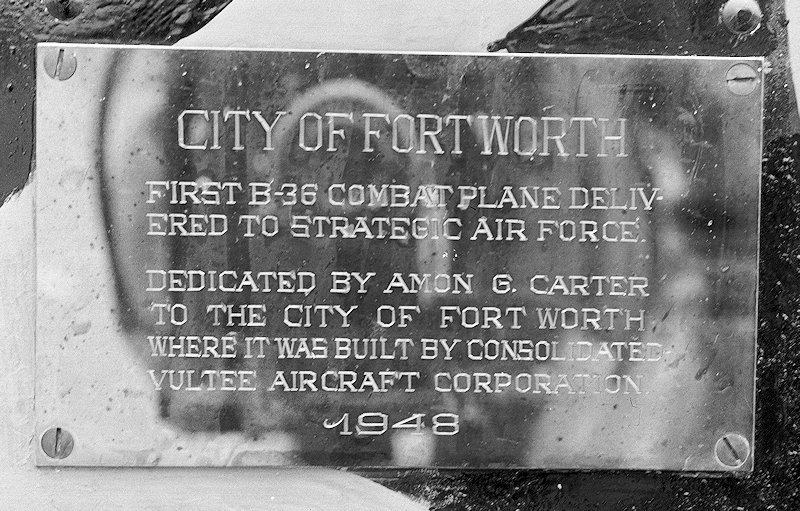

In August 1947 the bomber plant delivered its first production model B-36 (serial number 44 92004). Star-Telegram publisher Amon Carter, who had been instrumental in securing the bomber plant for Fort Worth, dedicated the aircraft to the city as the City of Fort Worth.

In August 1947 the bomber plant delivered its first production model B-36 (serial number 44 92004). Star-Telegram publisher Amon Carter, who had been instrumental in securing the bomber plant for Fort Worth, dedicated the aircraft to the city as the City of Fort Worth.

In this photo Carter is uncovering a dedication plate affixed to the nose of the plane. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

In this photo Carter is uncovering a dedication plate affixed to the nose of the plane. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

But the first City of Fort Worth was destined to have a short career in the Army Air Forces. It made its maiden flight over Fort Worth on August 28, 1947. Two days later it was flown to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio by Colonel Thomas P. Gerrity and Beryl Erickson. At Wright-Patterson the first City of Fort Worth was sacrificed to structural testing.

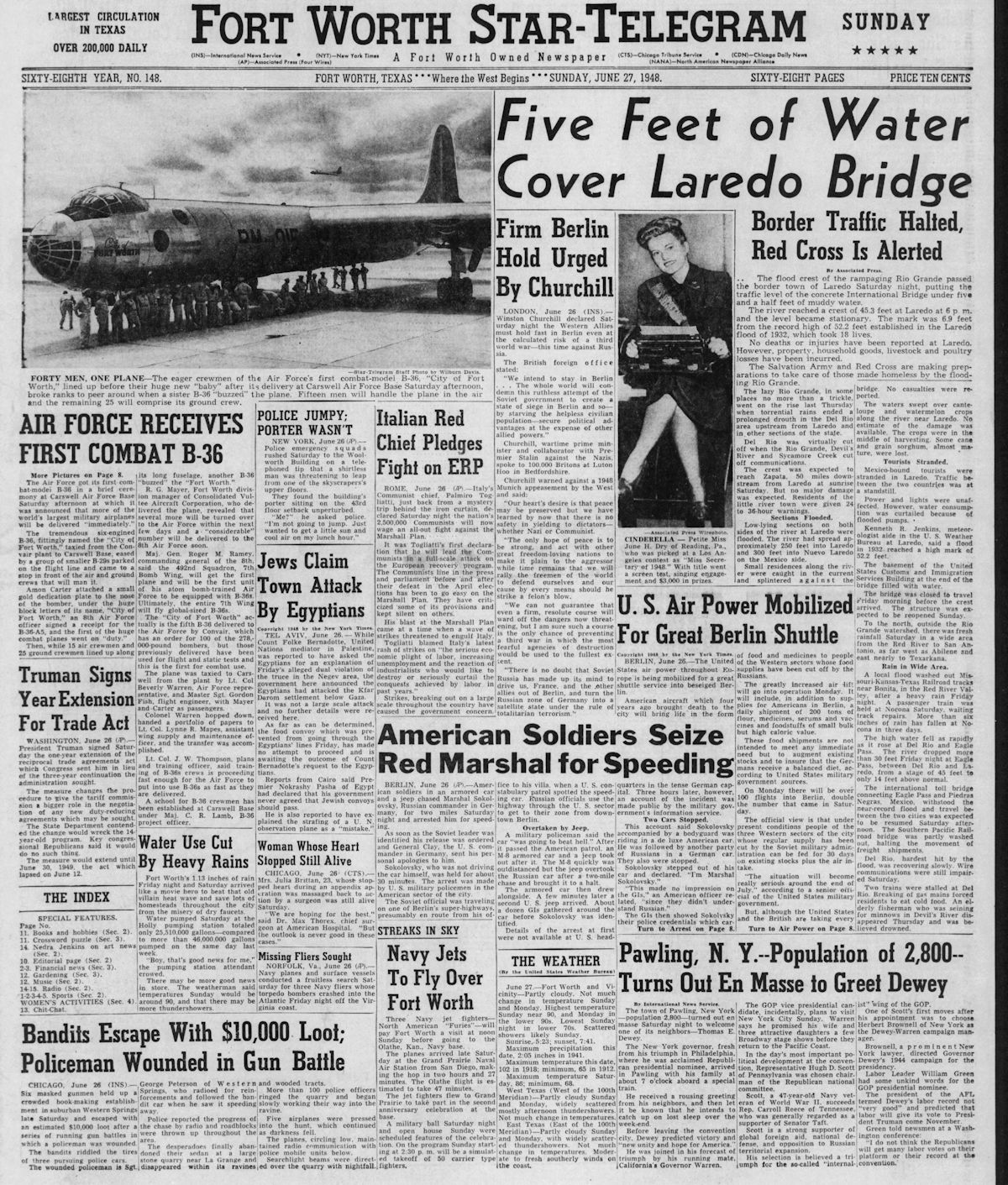

In June 1948 the bomber plant delivered the first combat-ready B-36 (serial number 44 92015) to the Army Air Forces. It was the second City of Fort Worth.

In June 1948 the bomber plant delivered the first combat-ready B-36 (serial number 44 92015) to the Army Air Forces. It was the second City of Fort Worth.

Amon Carter rode along as the second City of Fort Worth taxied from the bomber plant to adjacent Carswell Air Force Base. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Amon Carter rode along as the second City of Fort Worth taxied from the bomber plant to adjacent Carswell Air Force Base. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

In a ceremony at Carswell a representative of the Eighth Air Force signed a receipt for the airplane, and Amon Carter again affixed a dedication plate to the nose of the plane. (Photos from University of Texas at Arlington Library and Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company.)

The City of Fort Worth was a star attraction in 1948 at the dedication of New York City’s new Idlewild (today “John F. Kennedy International”) Airport.

The City of Fort Worth was a star attraction in 1948 at the dedication of New York City’s new Idlewild (today “John F. Kennedy International”) Airport.

The B-36 Peacemaker would become the primary nuclear weapons delivery vehicle of the Strategic Air Command during the early years of the Cold War. The planes were flown from SAC bases such as Carswell.

When writing about the giant bomber, writers could not resist ticking off the B-36’s vital statistics as if it were an airborne beauty queen: The fuselage was 162 feet long. The wing span (230 feet) was longer than the distance of the first Wright brothers flight in 1903. (This Lockheed Martin Aeronautics photo shows a B-25 medium bomber dwarfed by two B-36s.) The B-36’s bomb bay area was equivalent to four railroad box cars. Each airplane had 336 spark plugs. Thirty miles of wiring. Fuel capacity sufficient to take a motorist around the world eighteen times. Total engine power equal to that of nine locomotives. Propellers nineteen feet in diameter. The top of a B-36’s tail was forty-seven feet off the ground. Maximum takeoff weight of later models (see below) was 410,000 pounds.

When writing about the giant bomber, writers could not resist ticking off the B-36’s vital statistics as if it were an airborne beauty queen: The fuselage was 162 feet long. The wing span (230 feet) was longer than the distance of the first Wright brothers flight in 1903. (This Lockheed Martin Aeronautics photo shows a B-25 medium bomber dwarfed by two B-36s.) The B-36’s bomb bay area was equivalent to four railroad box cars. Each airplane had 336 spark plugs. Thirty miles of wiring. Fuel capacity sufficient to take a motorist around the world eighteen times. Total engine power equal to that of nine locomotives. Propellers nineteen feet in diameter. The top of a B-36’s tail was forty-seven feet off the ground. Maximum takeoff weight of later models (see below) was 410,000 pounds.

The B-36 could carry 132 five hundred-pound bombs or twenty-eight two thousand-pound bombs or four twelve thousand-pound bombs or one 43,600-pound T-12 Cloudmaker earth-penetrating bomb.

Alternately, by combining its bomb bays, the B-36 could carry one 41,400-pound Mark 17 fifteen-megaton thermonuclear bomb. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Alternately, by combining its bomb bays, the B-36 could carry one 41,400-pound Mark 17 fifteen-megaton thermonuclear bomb. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The B-36 dwarfed even a B-29. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The B-36 dwarfed even a B-29. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Personnel and equipment required to fly and maintain a B-36. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Personnel and equipment required to fly and maintain a B-36. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The first B-36s were powered by six propeller engines. In 1949 four jet engines were added to increase thrust. The combination of six prop engines and four jet engines was referred to as “six turning and four burning.” During the 1950s in Fort Worth you didn’t have to see a B-36 to know it was in the sky overhead. The drone was unmistakable.

With the added four jets, a B-36 had a top speed of 435 miles per hour, a ceiling of forty-three thousand feet, and a range of up to twelve thousand miles.

SAC commander General Curtis LeMay said: “I believe we can get the B-36 over a target and not have the enemy know it is there until the bombs hit.”

This B-36 has six turning and four burning. (Photo from Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company.)

This B-36 has six turning and four burning. (Photo from Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company.)

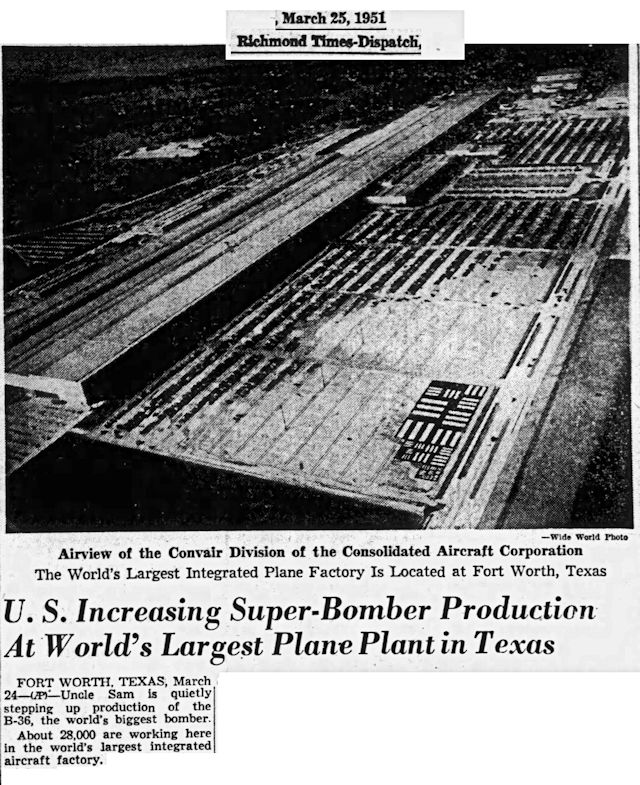

By 1951 the bomber plant employed twenty-eight thousand people. Fort Worth’s population in 1950 was 279,000, meaning that about one person in ten worked at the bomber plant. The concrete foundation of the plant’s .9-mile-long assembly building would pave a four-lane highway for thirty miles. Some workers used bicycles and motorscooters to get around the huge building.

By 1951 the bomber plant employed twenty-eight thousand people. Fort Worth’s population in 1950 was 279,000, meaning that about one person in ten worked at the bomber plant. The concrete foundation of the plant’s .9-mile-long assembly building would pave a four-lane highway for thirty miles. Some workers used bicycles and motorscooters to get around the huge building.

B-36s on the assembly line. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

B-36s on the assembly line. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The B-36 that would become the third City of Fort Worth was built in 1954 as “B-36-J-III 52-2827.” It was the last of 385 B-36s produced by the bomber plant. (Photo from University of North Texas.)

The B-36 that would become the third City of Fort Worth was built in 1954 as “B-36-J-III 52-2827.” It was the last of 385 B-36s produced by the bomber plant. (Photo from University of North Texas.)

More than eleven thousand people turned out to see the last B-36 take off for its new home at Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane, Washington. During a ceremony marking the end of production, six Carswell B-36s flew over in formation at an altitude of one thousand feet.

More than eleven thousand people turned out to see the last B-36 take off for its new home at Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane, Washington. During a ceremony marking the end of production, six Carswell B-36s flew over in formation at an altitude of one thousand feet.

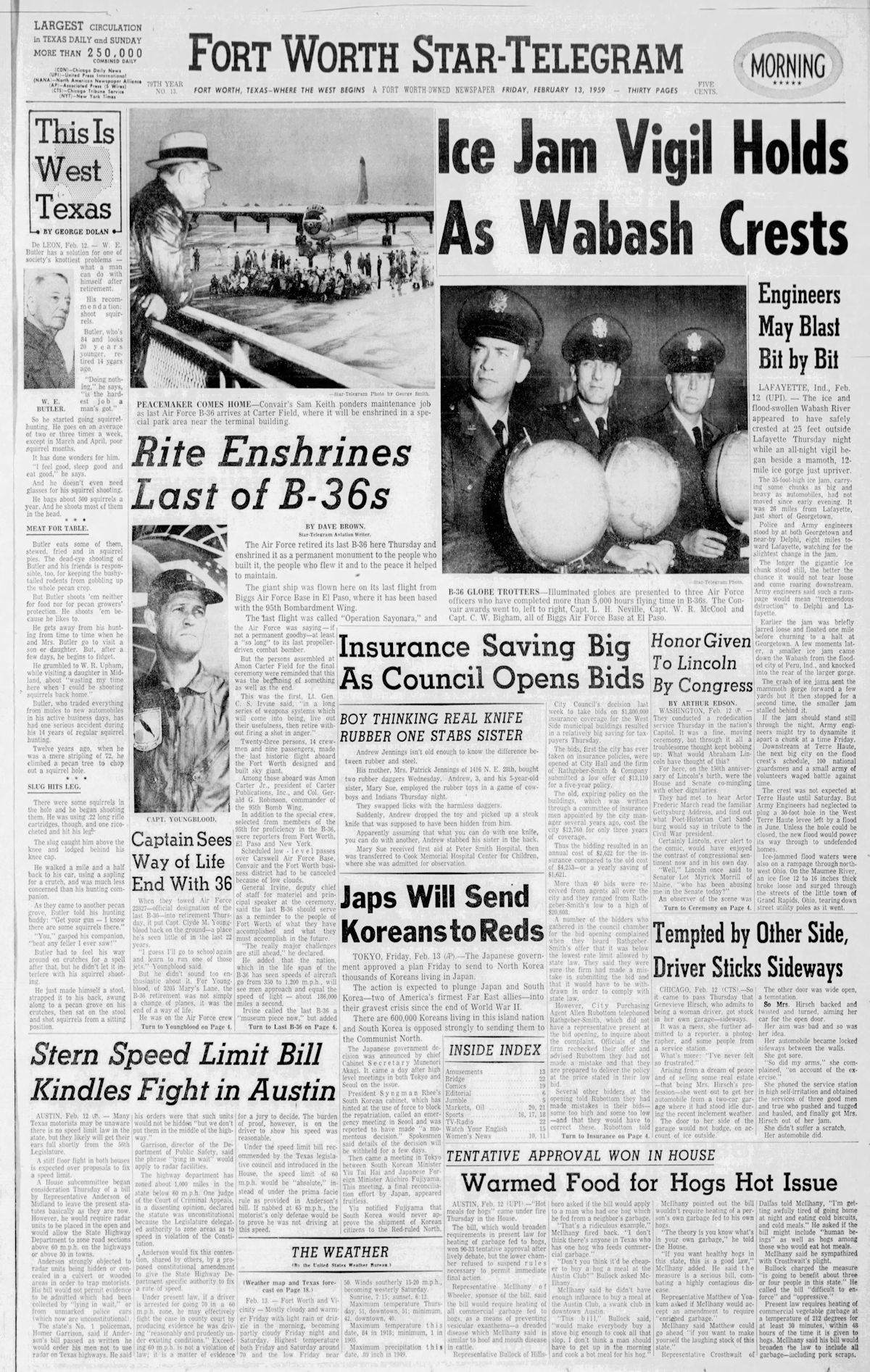

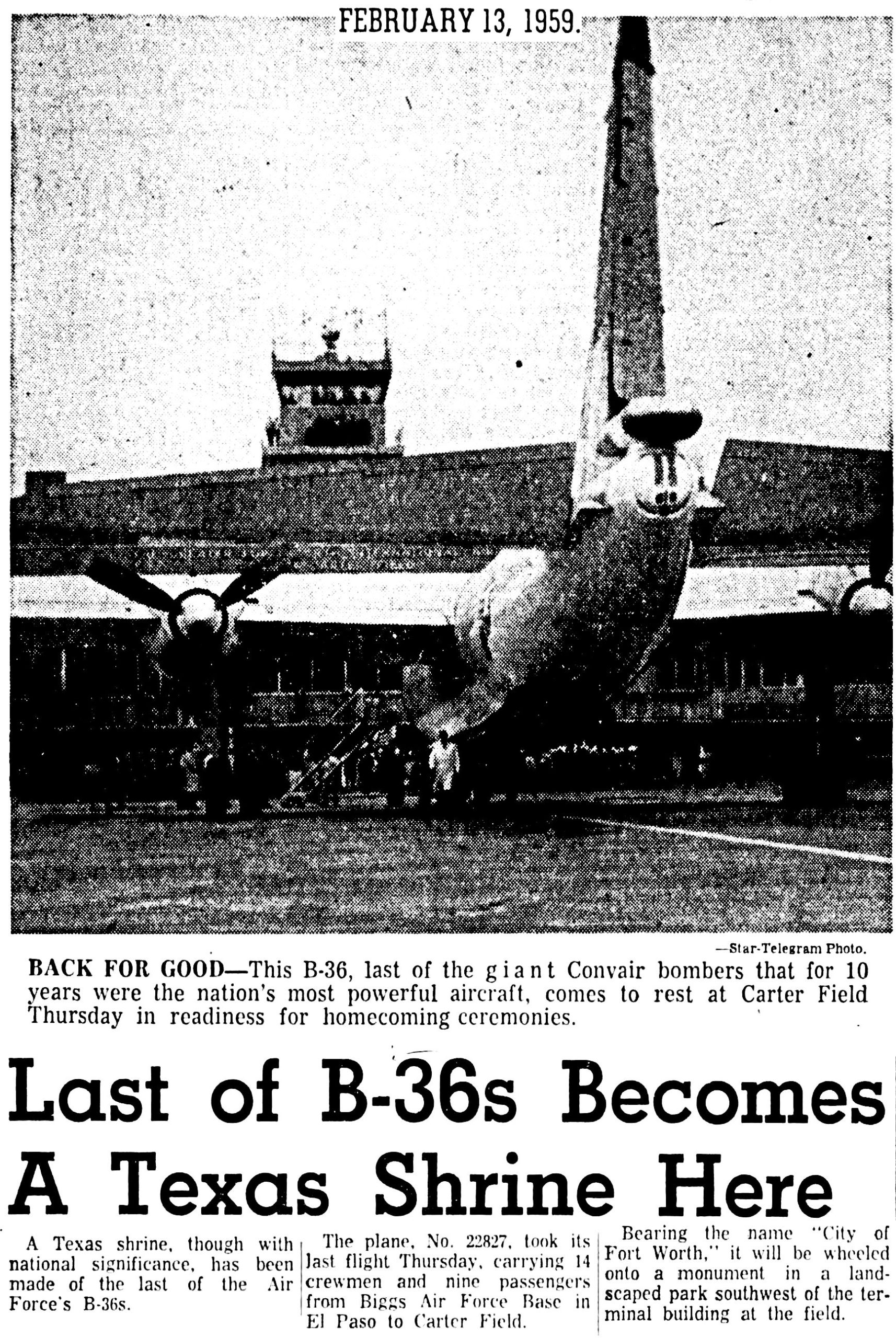

B-36 52-2827 was the last B-36 built and also the last B-36 to fly. In 1959 it was flown from Biggs Air Force Base in El Paso to Amon Carter Field in Fort Worth on a goodbye flight named “Operation Sayonara.” Among the passengers was Amon Carter’s son Amon Jr.

B-36 52-2827 was the last B-36 built and also the last B-36 to fly. In 1959 it was flown from Biggs Air Force Base in El Paso to Amon Carter Field in Fort Worth on a goodbye flight named “Operation Sayonara.” Among the passengers was Amon Carter’s son Amon Jr.

Upon arrival in Fort Worth, B-36 52-2827 was christened City of Fort Worth, becoming the third of the triplets, and displayed at Amon Carter Field, which would become Greater Southwest International Airport.

Upon arrival in Fort Worth, B-36 52-2827 was christened City of Fort Worth, becoming the third of the triplets, and displayed at Amon Carter Field, which would become Greater Southwest International Airport.

With the advent of the jet age in the early 1950s, propeller-driven bombers had been rendered obsolete. In 1955 the B-36 Peacemaker was replaced by the B-52 Stratofortress.

The Peacekeeper had earned its name. It kept the peace: No B-36 dropped a bomb in wartime. A few modified B-36s flew high-altitude reconnaissance missions during the Korean War.

While being on display at Amon Carter Field/Greater Southwest International Airport the City of Fort Worth fell victim to vandalism and the extremes of Texas weather. In 1974 the airport closed after the opening of Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport in 1973, and the third City of Fort Worth was disassembled and moved in increments to Carswell Air Force Base. In 1978 the last part—a 146-foot-long wing—was moved across town on Highway 121 and the Loop. At Carswell the aircraft was restored by volunteers, many of them retired bomber plant workers who had worked on the B-36 assembly line.

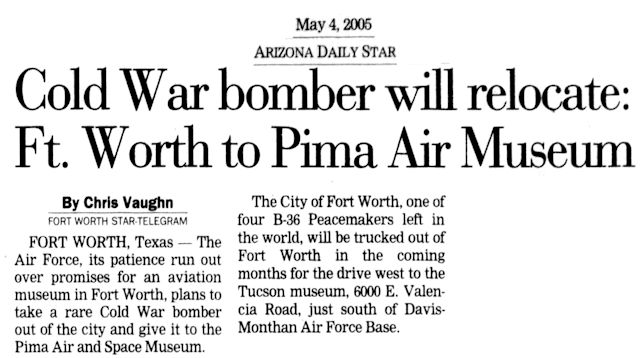

The third City of Fort Worth, which was on loan from the Air Force, was displayed at the Museum of Aviation adjacent to Carswell.

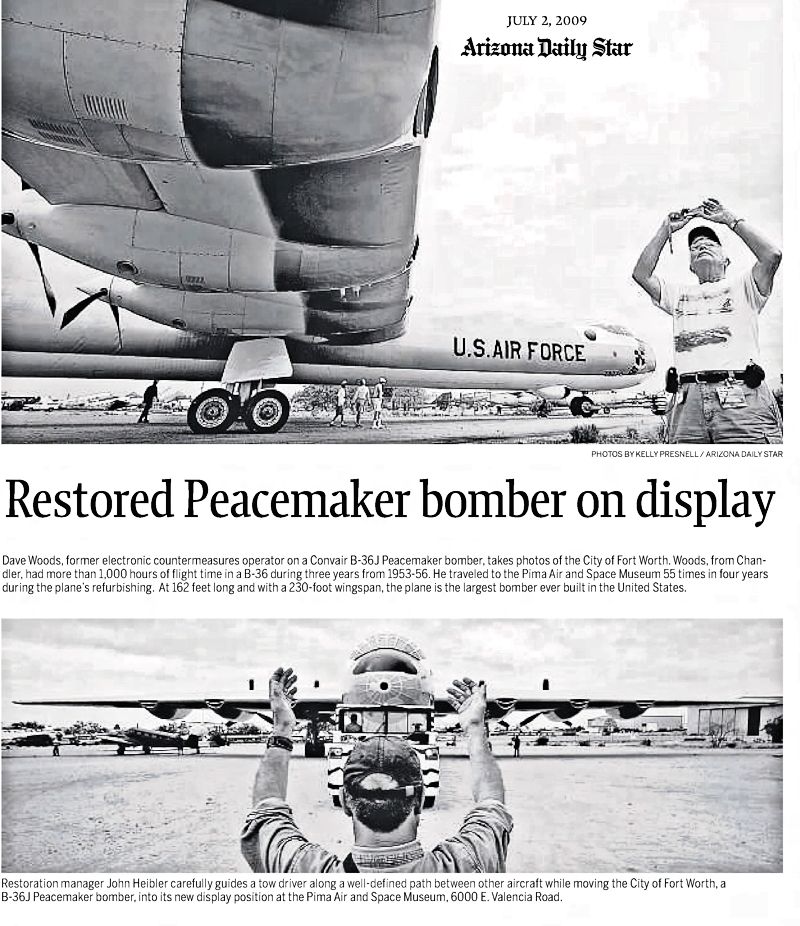

But after the city failed to raise enough money to properly display the aircraft—especially in light of the extremes of Texas weather—the Air Force reclaimed it. The City of Fort Worth was disassembled and trucked to the Pima Air and Space Museum in Arizona, where it was restored for display in a location where the climate would retard deterioration of the fifty-one-year-old aircraft.

But after the city failed to raise enough money to properly display the aircraft—especially in light of the extremes of Texas weather—the Air Force reclaimed it. The City of Fort Worth was disassembled and trucked to the Pima Air and Space Museum in Arizona, where it was restored for display in a location where the climate would retard deterioration of the fifty-one-year-old aircraft.

In 2009 B-36-J-III 52-2827 went on display in Arizona—without its City of Fort Worth designation. Today the last of the City of Fort Worth triplets is one of only four of the 385 B-36s built at the bomber plant that survive. None is airworthy. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 2009 B-36-J-III 52-2827 went on display in Arizona—without its City of Fort Worth designation. Today the last of the City of Fort Worth triplets is one of only four of the 385 B-36s built at the bomber plant that survive. None is airworthy. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Footnote: The 1955 movie Strategic Air Command starring Jimmy Stewart was filmed in part at Carswell. In the control tower scene the bomber plant’s assembly building can be seen in the background and B-36s in the middle ground. In the bottom scene Stewart is walking with actor Harry Morgan alongside B-36 serial number 5734. Fame is fleeting: In 1957 B-36 5734 was scrapped.

Footnote: The 1955 movie Strategic Air Command starring Jimmy Stewart was filmed in part at Carswell. In the control tower scene the bomber plant’s assembly building can be seen in the background and B-36s in the middle ground. In the bottom scene Stewart is walking with actor Harry Morgan alongside B-36 serial number 5734. Fame is fleeting: In 1957 B-36 5734 was scrapped.

YouTube videos of the B-36:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMcYQsc72Lc&feature=emb_logo

https://youtu.be/4qkN9APkeqs

Other posts about the B-36:

“Just . . . Earning Shoes for the Baby”: The XB-36 “Went Insane”

Short Flight to Tragedy: “I Saw We Were Running Out of Runway”

“A B-36 Flies Fine on 5 Engines” (How About 3?)

B-36 Peacemaker Museum

Vintage Flying Museum

Posts About Aviation and War in Fort Worth History

When I was a kid my parents took me to see it at GSW,and later I visited it again at Carswell. My Dad also took me to the grand opening of DFW Airport. I’m now a mechanic at American Airlines. I guess it was my destiny! I’m going to make a point of going to see the plane at PIMA!

Like anyone growing up here in the ’50s, you couldn’t help but look skyward when a B-36 flew over. Really regret that Fort Worth couldn’t find a way to keep a B-36 on display. Would’ve been an overwhelming tourist attraction almost as iconic as our 1895 courthouse.

Don’t get me started. Fort Worth should have a B-36 and a steam locomotive on static display.

My Cub Scout den visited the B-36 parked at Great Southwest International Airport. We crawled all through that plane. It was not secured at all. Many gauges were missing. There was a tunnel with a sled for moving from forward to aft cabins. We gave that feature a good workout. It was fun. In years to come, I worked on R-4360 engines on another aircraft. Later still, I did my own tour at the bomber plant before retiring.

I have heard about the tunnel with the sled. Makes me claustrophobic even to think about it.

I remember it well sitting out in front of GSW Airport, having been a stewardess for Ft. Worth’s Central Airlines and based there.I also remember that Jimmy Stewart was one of the investors in Central airlines and remained on the board for years. Now I understand why one of our pilots remarked as we passed the bomber that it was pushing and pulling.

After you mentioned it, I researched Central Airlines last week. Don’t know when I will run the post.