By the time America entered World War II on December 8, 1941, Fort Worth had been helping the Allied powers in Europe for thirteen months.

We can begin the story in 1936, when Consolidated Aircraft Corporation of San Diego began building PBY “flying boat” bombers for the Navy. (Why “PBY”? “PB” stands for “patrol bomber.” “Y” is the code letter that the Navy assigned to manufacturer Consolidated.) (Photo from Wikipedia.)

We can begin the story in 1936, when Consolidated Aircraft Corporation of San Diego began building PBY “flying boat” bombers for the Navy. (Why “PBY”? “PB” stands for “patrol bomber.” “Y” is the code letter that the Navy assigned to manufacturer Consolidated.) (Photo from Wikipedia.)

After the Allied powers of Europe went to war against Germany in 1939, in 1940 Consolidated won a contract to build PBYs for England (and Canada) and France. The U.S. Army Air Forces also flew PBYs. More than three thousand PBYs would be built from 1936 to 1945.

After the Allied powers of Europe went to war against Germany in 1939, in 1940 Consolidated won a contract to build PBYs for England (and Canada) and France. The U.S. Army Air Forces also flew PBYs. More than three thousand PBYs would be built from 1936 to 1945.

By March 1940 American aircraft plants had sent sixteen hundred warplanes to England and France.

Also that month Captain Robert S. Fogg, seaplane specialist of the Civil Aeronautics Authority, was on a mission unrelated to sending American warplanes to Europe: The CAA planned to build inland seaplane bases across the United States to provide “facilities for sportsmen and other private owners.” Oh, there was a possibility, Fogg said, that later the bases might be used for commercial seaplanes.

Also that month Captain Robert S. Fogg, seaplane specialist of the Civil Aeronautics Authority, was on a mission unrelated to sending American warplanes to Europe: The CAA planned to build inland seaplane bases across the United States to provide “facilities for sportsmen and other private owners.” Oh, there was a possibility, Fogg said, that later the bases might be used for commercial seaplanes.

And he added that Navy and Coast Guard planes might use the seaplane bases in an emergency. But he said the bases were not intended to be part of a national defense program.

On March 4 Fogg landed his little Fairchild seaplane on Lake Worth and inspected the lake as a possible site for a seaplane base.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “‘Lake Worth is ideal for a landing base,’” Captain Fogg said. “He will recommend a site for the landing base after his inspection is completed Tuesday.

“The plan of construction for the base is for the city to furnish materials, with the NYA [National Youth Administration] building the base and the CAA providing inspection and supervision.”

The CAA indeed approved Lake Worth, and the local NYA branch was given plans to build a rudimentary seaplane base: “a floating dock 10 by 22 feet, equipped with rubber bumpers, and connected with the shore by a pontoon walkway.”

The CAA indeed approved Lake Worth, and the local NYA branch was given plans to build a rudimentary seaplane base: “a floating dock 10 by 22 feet, equipped with rubber bumpers, and connected with the shore by a pontoon walkway.”

Cost to the city for building materials: $150 ($2,800 today).

Fast-forward to November 1940. According to aviation historian Jeff Rhodes, “On 22 November 1940, Consolidated Aircraft Chief Test Pilot Bill Wheatley contacted newspaper publisher and Fort Worth, Texas, civic booster Amon G. Carter, explaining the company had been ordered to transfer 200 PBY Catalina patrol seaplanes from San Diego, California, to Britain and that the crews were in immediate need of a layover point.”

Captain Fogg’s rudimentary seaplane base built for sportsmen was about to grow up and go to war.

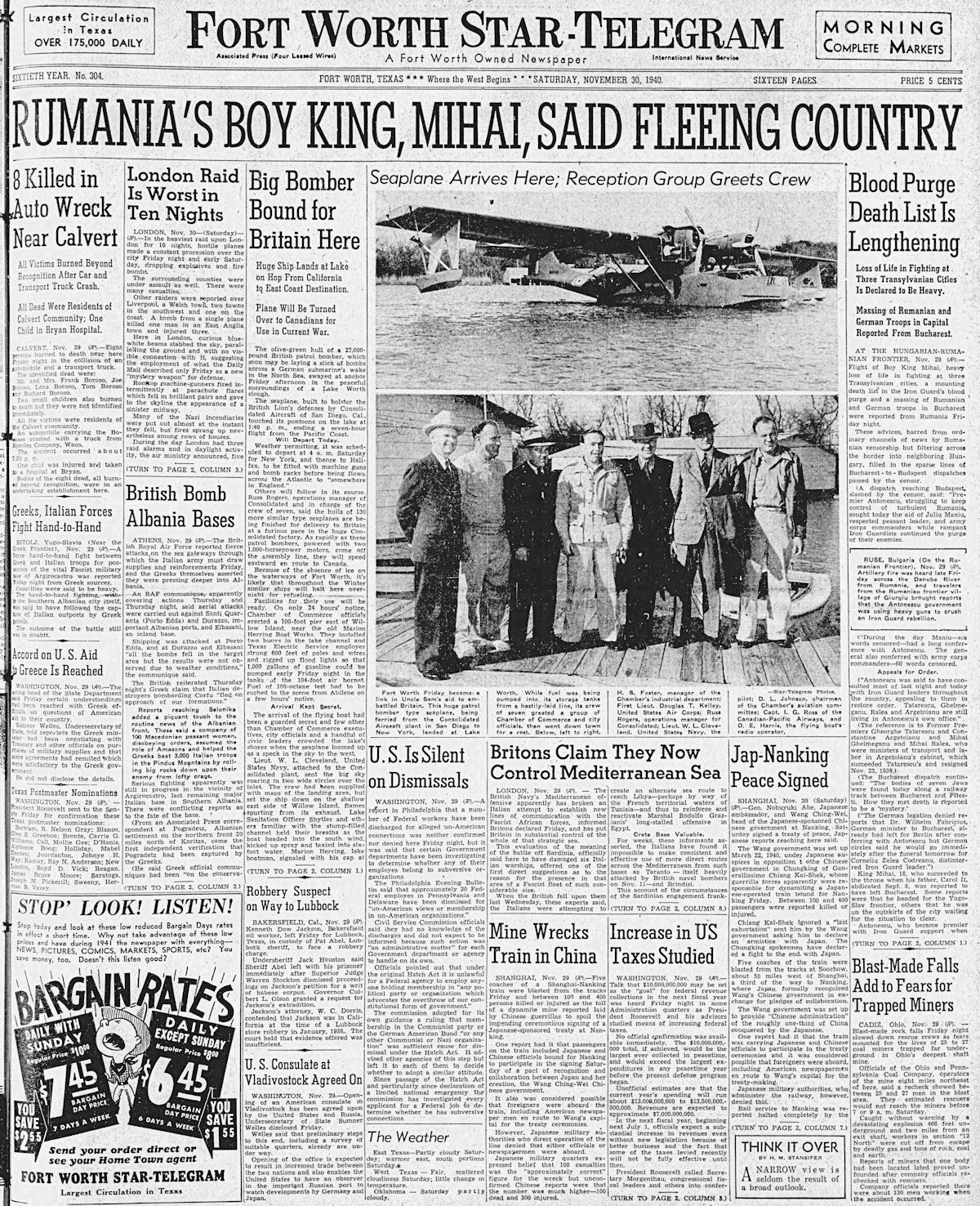

The Star-Telegram wrote on November 30: “On only 24 hours’ notice, Chamber of Commerce officials erected a 100-foot pier east of Willow Island near the old Marion Herring Boat Works. They installed two buoys in the lake channel, and Texas Electric Service employees strung 600 feet of poles and wires and rigged up flood lights.”

The Star-Telegram wrote on November 30: “On only 24 hours’ notice, Chamber of Commerce officials erected a 100-foot pier east of Willow Island near the old Marion Herring Boat Works. They installed two buoys in the lake channel, and Texas Electric Service employees strung 600 feet of poles and wires and rigged up flood lights.”

William G. Fuller, municipal airport (Meacham Field) manager, directed a crew of NYA workers and Meacham Field workers in running a gasoline line to the water’s edge.

Rhodes says, “In just eight days, Carter, with the help of the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, arranged for fuel, food, lodging for the flight crews, and moorings for the aircraft in Lake Worth.”

The chamber of commerce added lights at Willow Island, Goat Island, and Mosque Point.

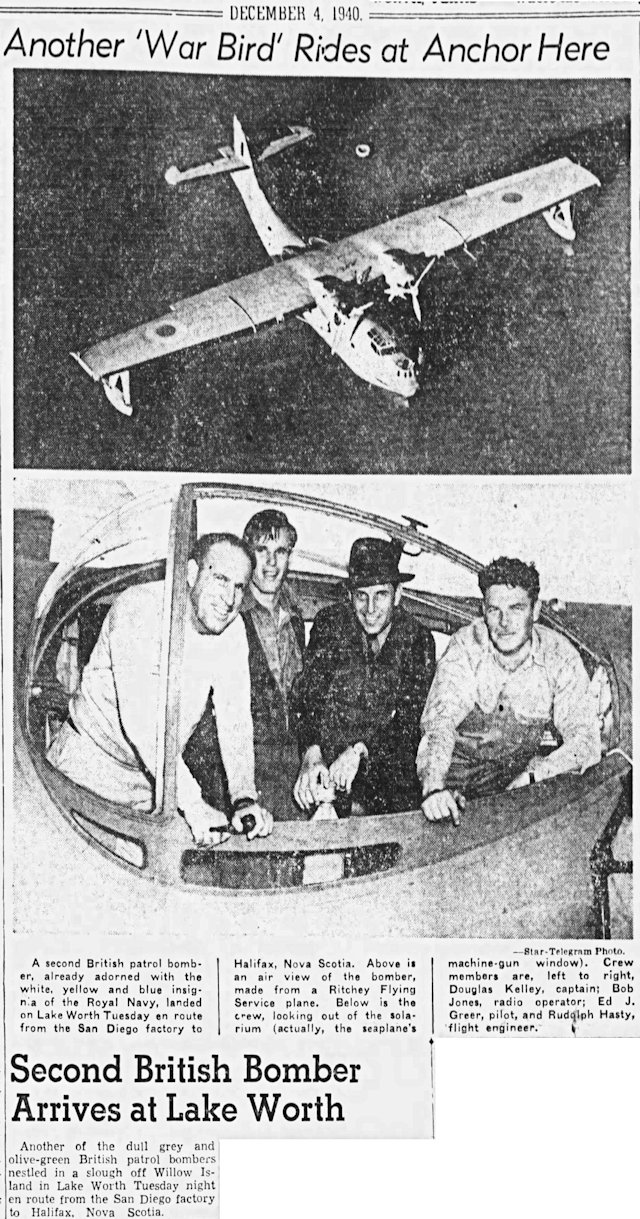

One week after test pilot Wheatley contacted Amon Carter, the first Consolidated PBY bound for England landed at the expanded seaplane base.

One week after test pilot Wheatley contacted Amon Carter, the first Consolidated PBY bound for England landed at the expanded seaplane base.

On the plane were seven crew members and the operations manager for Consolidated.

The plane was moored five hundred feet from the shore. Fuller and Amon Carter rode out to the plane in a speedboat to greet the crew.

Aviation fuel had been rushed to the seaplane base from Abilene, and one thousand gallons were pumped into the tanks of the PBY.

That night Carter hosted the plane’s pilot and the Consolidated operations manager at his suite at the Fort Worth Club. Crewmen stayed in local hotels overnight.

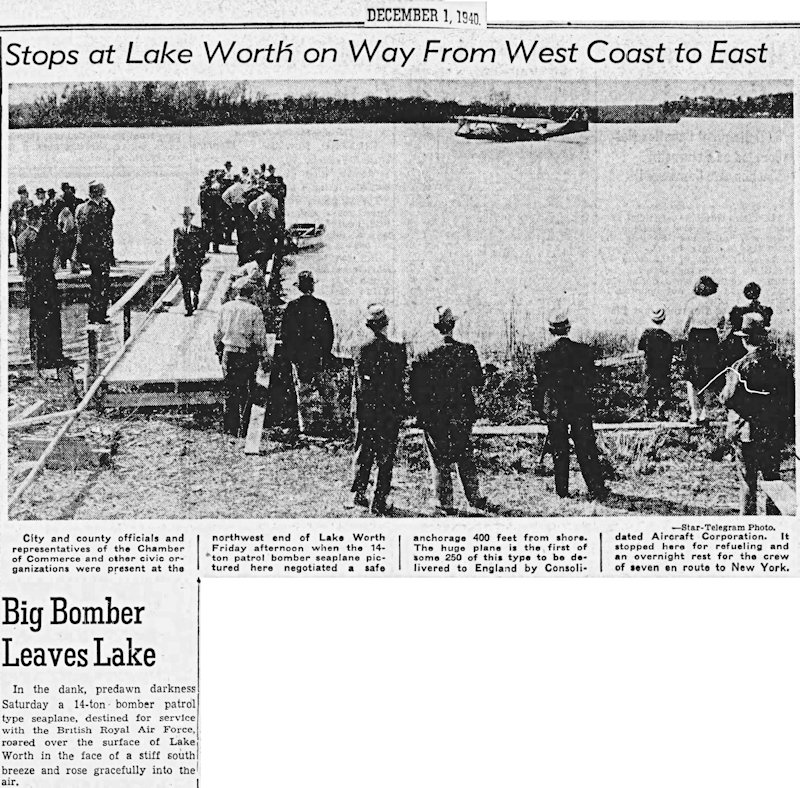

The PBY took off the next day, skimming over the lake for a half-mile before becoming airborne.

The PBY took off the next day, skimming over the lake for a half-mile before becoming airborne.

The plane was flown to Halifax to be fitted with machine guns and bomb racks and then ferried on to a classified location in England to join the war. PBYs were armed with three thirty-caliber machine guns and two fifty-caliber machine guns and could carry four thousand pounds of bombs or depth charges.

The second Consolidated PBY landed at the seaplane base on December 3 and took off the next day. Because of a shortage of pilots, PBYs were backlogged at the San Diego factory waiting to be ferried to England. Fort Worth was told to expect a PBY every three or four days. Because Lake Worth rarely ices over, the planes could land year around.

The second Consolidated PBY landed at the seaplane base on December 3 and took off the next day. Because of a shortage of pilots, PBYs were backlogged at the San Diego factory waiting to be ferried to England. Fort Worth was told to expect a PBY every three or four days. Because Lake Worth rarely ices over, the planes could land year around.

The pilot of the first plane to land here was also the pilot of the second plane. He had crossed the continent twice that week in PBYs, which had a maximum speed of 196 miles per hour. The flight from San Diego to Lake Worth took seven hours.

Fast-forward one month. Fort Worth had quickly grown accustomed to Consolidated PBY traffic at its seaplane base. By January 3, 1941 reports on arrivals and departures were demoted from a lead story on the front page to briefs on an inside page.

Fast-forward one month. Fort Worth had quickly grown accustomed to Consolidated PBY traffic at its seaplane base. By January 3, 1941 reports on arrivals and departures were demoted from a lead story on the front page to briefs on an inside page.

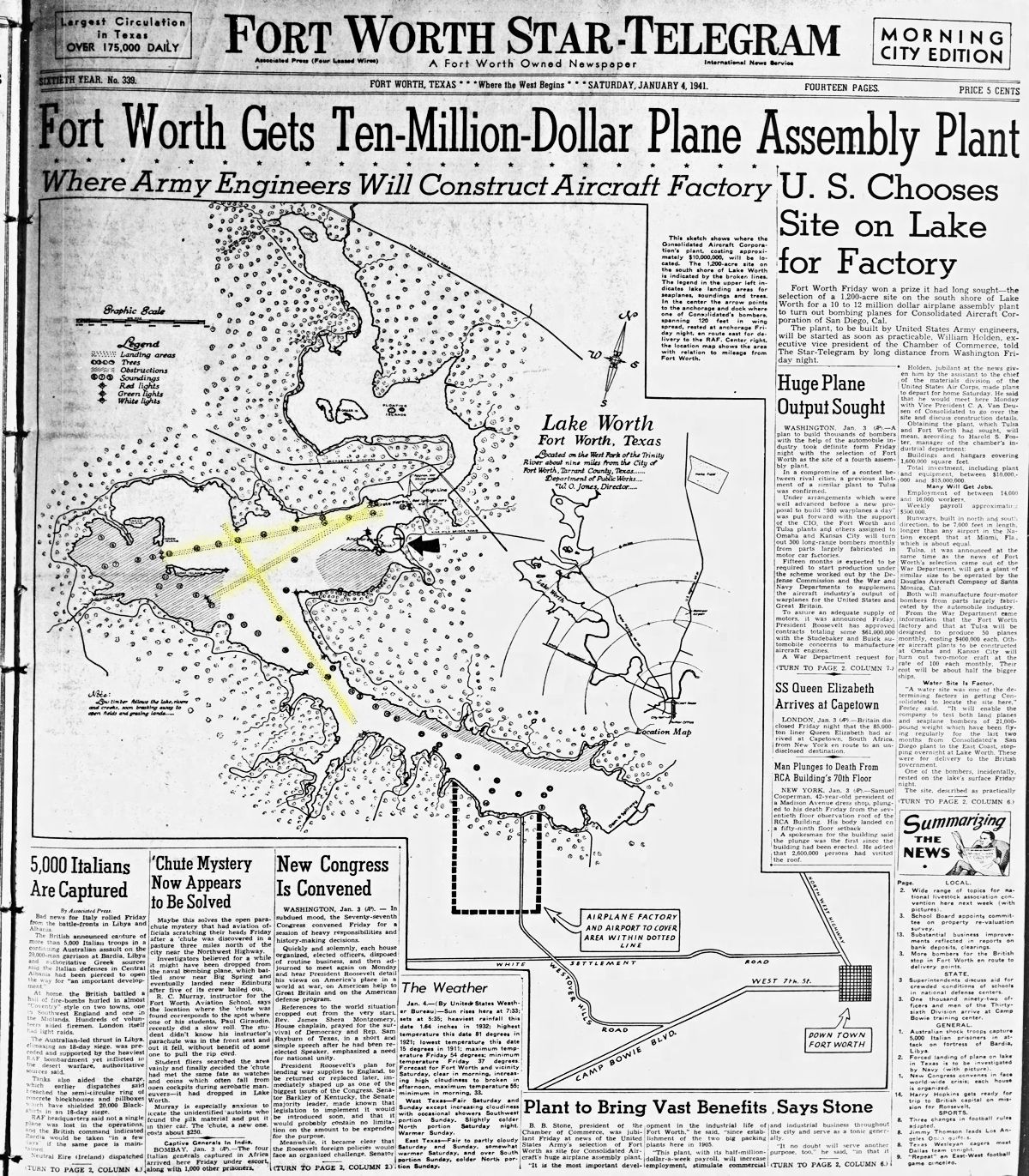

Ah, but the next day, January 4, the seaplane base was back on the front page as the Star-Telegram announced that Consolidated Aircraft Corporation and the federal government had selected Fort Worth as the site of a $10 million ($176 million today) bomber plant that would employ thousands of workers.

Ah, but the next day, January 4, the seaplane base was back on the front page as the Star-Telegram announced that Consolidated Aircraft Corporation and the federal government had selected Fort Worth as the site of a $10 million ($176 million today) bomber plant that would employ thousands of workers.

And where would the bomber plant—and adjacent training airfield—be built?

On Lake Worth near the seaplane base.

Yes, Amon Carter had done it again. In addition to convincing Consolidated to use Lake Worth as a seaplane base, Carter had headed a chamber of commerce committee tasked with lobbying Consolidated and the federal government to build a military airplane plant here.

Carter pointed out that Consolidated already was using Fort Worth’s seaplane base. If Consolidated ever were to build seaplanes at its Fort Worth bomber plant, that seaplane base would come in mighty handy.

Just sayin’.

The Star-Telegram wrote, “The world’s largest producer of flying boats, Consolidated eventually may build seaplanes as well as land planes at the Lake Worth base. The water advantage offered by the lake front site was an influencing factor in causing Consolidated officials to favor establishment of the plant here.”

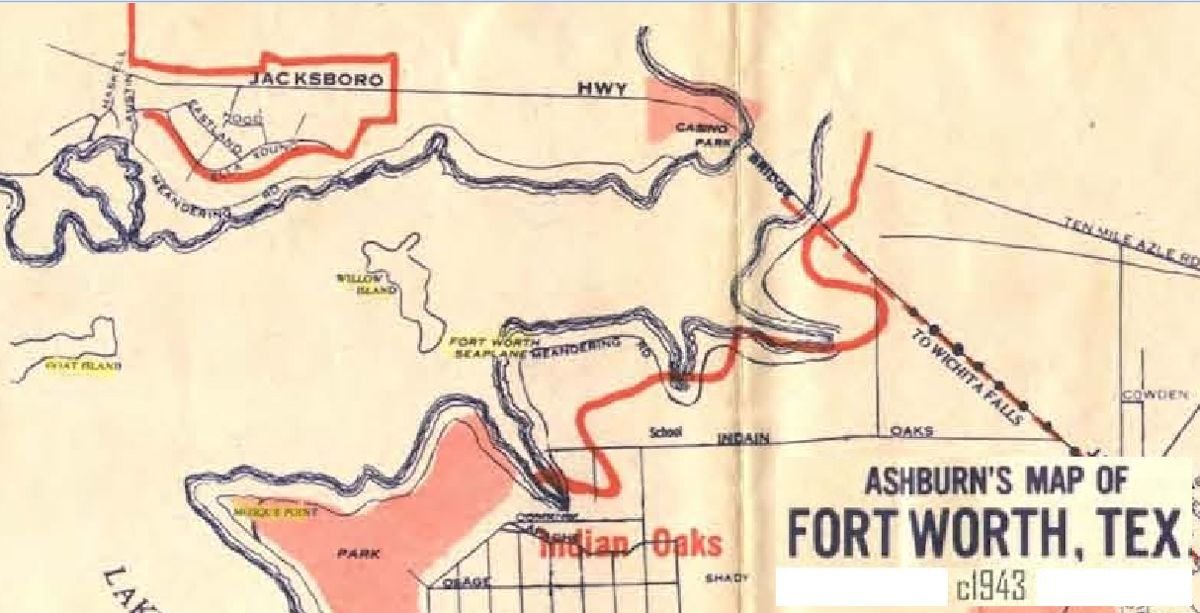

See those three yellow lines on the map? Those are landing lanes for seaplanes. The black arrow points to the seaplane base.

Historian Rhodes added: “The quick response from Carter and the Chamber of Commerce [to Consolidated’s need for the seaplane base in 1940] later helped convince Consolidated Aircraft to build a manufacturing facility in Fort Worth.”

Seven weeks later, on February 27, Fort Worth’s future flew into town on four twelve hundred-horsepower Pratt & Whitney engines. A B-24 Liberator, which Fort Worth’s bomber plant would be building within months, landed at Meacham Field and drew so many spectators that a special detail of police was dispatched to control automobile traffic to the airport.

Seven weeks later, on February 27, Fort Worth’s future flew into town on four twelve hundred-horsepower Pratt & Whitney engines. A B-24 Liberator, which Fort Worth’s bomber plant would be building within months, landed at Meacham Field and drew so many spectators that a special detail of police was dispatched to control automobile traffic to the airport.

Like the seaplane base, Meacham Field would be used during the war as a stop for U.S.-built warplanes being ferried to Europe.

In fact, February 27 was a twofer for Fort Worth: In addition to the B-24, another Consolidated PBY landed, joining seven others floating on the lake. The B-24 and PBYs were bound for Europe and had landed here to refuel and to wait out bad weather on the east coast.

Captain Douglas C. Kelley, who had been a crew member of the first two PBYs to land at Lake Worth in 1940, was pilot of the B-24.

Another familiar face on February 27 was that of Captain Fogg, whom the Star-Telegram called the “daddy” of the seaplane base. The newspaper pointed out that Fogg’s “baby” had grown into something he could not have foreseen a year earlier.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “Fort Worth’s dock is the first to be completed in Texas, the first inland dock ever started. Now virtually complete, it is ready for dedication. The project includes a shelter house for fuel pumps, buoy guides and anchor stakes in the water, a refueling dock, and shore lights to mark the landing cove for night fliers.”

In the photos, note that the seaplane base now had a formal name and signage.

On May 7, 1941 the Star-Telegram reported that four anchorages were being added to the four existing anchorages at the seaplane base.

On May 7, 1941 the Star-Telegram reported that four anchorages were being added to the four existing anchorages at the seaplane base.

Seven months later the seaplane base took on added importance as America entered the war.

In April 1942 the bomber plant rolled out its first B-24. Now the sky over Fort Worth was filled with airplanes built at the plant, with warplanes landing to lay over at Meacham Field, and with warplanes landing to lay over at the seaplane base.

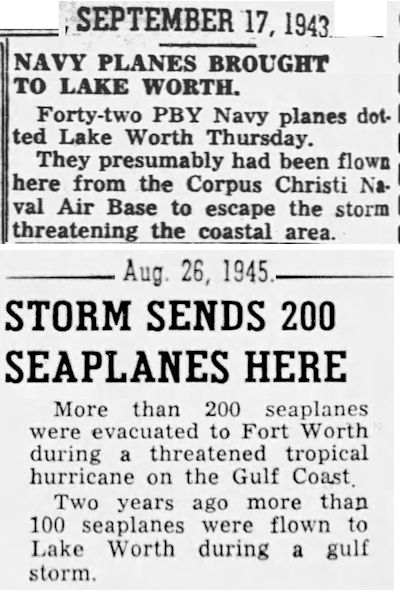

Sometimes eight seaplane anchorages weren’t nearly enough. The U.S. military soon found another use for Fort Worth’s seaplane base. On at least two occasions—in 1943 and 1945—military seaplanes stationed on the Texas gulf were flown to the seaplane base here to escape potentially damaging weather.

Sometimes eight seaplane anchorages weren’t nearly enough. The U.S. military soon found another use for Fort Worth’s seaplane base. On at least two occasions—in 1943 and 1945—military seaplanes stationed on the Texas gulf were flown to the seaplane base here to escape potentially damaging weather.

A flock of PBYs floating on Lake Worth, flown up from the Texas gulf to avoid a storm. (Photo from Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company.)

A flock of PBYs floating on Lake Worth, flown up from the Texas gulf to avoid a storm. (Photo from Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company.)

When a seaplane was about to land on the lake, government boats were dispatched from the base to clear civilian boats from the landing lane. Tom Wade, custodian of the seaplane base, said civilian boaters sometimes followed in the wake of the fast government boats and capsized, which not only was dangerous to the boaters but also impeded the landing of seaplanes. It was a dangerous sport, Wade said, that might result in pleasure craft being banned from the lake for the duration of the war.

When a seaplane was about to land on the lake, government boats were dispatched from the base to clear civilian boats from the landing lane. Tom Wade, custodian of the seaplane base, said civilian boaters sometimes followed in the wake of the fast government boats and capsized, which not only was dangerous to the boaters but also impeded the landing of seaplanes. It was a dangerous sport, Wade said, that might result in pleasure craft being banned from the lake for the duration of the war.

Late in 1945, with the war ended, custodian Wade was called to Long Beach, California to give technical advice on building mooring and refueling facilities for the giant HK-1 (“H” for “Hughes,” “K” for “Kaiser”) seaplane. The HK-1 was the brainchild of entrepreneur Howard Hughes and Henry J. Kaiser, builder of automobiles and ships. With a wingspan of 350 feet, the HK-1 was the largest aircraft yet built, designed to carry one thousand passengers or 750 fully equipped troops or two thirty-ton Sherman tanks.

Late in 1945, with the war ended, custodian Wade was called to Long Beach, California to give technical advice on building mooring and refueling facilities for the giant HK-1 (“H” for “Hughes,” “K” for “Kaiser”) seaplane. The HK-1 was the brainchild of entrepreneur Howard Hughes and Henry J. Kaiser, builder of automobiles and ships. With a wingspan of 350 feet, the HK-1 was the largest aircraft yet built, designed to carry one thousand passengers or 750 fully equipped troops or two thirty-ton Sherman tanks.

The giant HK-1 evolved into Howard Hughes’s behemoth Spruce Goose. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The giant HK-1 evolved into Howard Hughes’s behemoth Spruce Goose. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 1945 the city announced that the seaplane base had paid for itself through its sales of gasoline—500,000 gallons—to Convair (Consolidated became “Consolidated-Vultee” [Convair] in 1943) for its planes. Note that by 1945 the city had spent $17,000 ($245,000 today) on the seaplane base that originally had cost it only $150.

In 1945 the city announced that the seaplane base had paid for itself through its sales of gasoline—500,000 gallons—to Convair (Consolidated became “Consolidated-Vultee” [Convair] in 1943) for its planes. Note that by 1945 the city had spent $17,000 ($245,000 today) on the seaplane base that originally had cost it only $150.

With the end of the war later in 1945 Convair stopped using the seaplane base, and Lake Worth and its seaplane base, like the surviving soldiers and sailors, returned to civilian life. A company began offering seaplane instruction and rides near the base.

With the end of the war later in 1945 Convair stopped using the seaplane base, and Lake Worth and its seaplane base, like the surviving soldiers and sailors, returned to civilian life. A company began offering seaplane instruction and rides near the base.

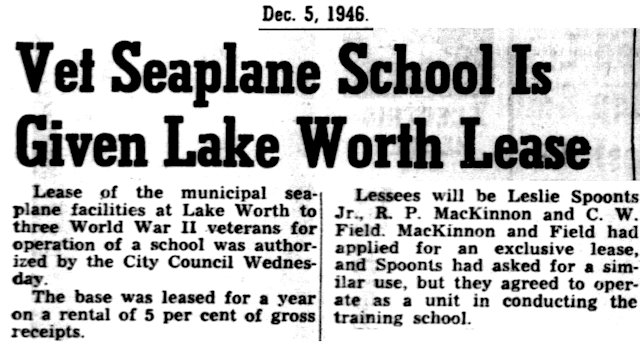

And in December 1946 the city leased the base to three veterans to operate a seaplane school.

And in December 1946 the city leased the base to three veterans to operate a seaplane school.

Since its beginning for use by “sportsmen,” Fort Worth’s seaplane base had been a halfway house to more than seven hundred PBYs on their way to win the war.

Posts About Aviation and War in Fort Worth History