The Cellar opened in 1959 when beatnik coffeehouses were the latest fad (see Part 1). In fact, the motto of the Cellar was “coffee and confusion.” But the Cellar would not remain a traditional coffeehouse long, and it would quickly become known more for controversy than confusion. With the business savvy of owner Pat Kirkwood, the Cellar would outlive the coffeehouse era to evolve with American culture from the straitlaced fifties through the anything-goes sixties. The Cellar would evolve from beatniks to hippies, from poetry and chess to guns and knives, from acoustic folk music to amplified rock music, from espresso coffee to Everclear alcohol, from waitresses in leotards or fish-net stockings to waitresses in bra and panties, bikinis, or, when the mood struck, even less.

The Cellar would come to be called “dingy,” a “sore spot,” a “public nuisance,” a “human cesspool,” and, yes, a “murky center of sybaritic hedonism.”

And for thirteen years Pat Kirkwood would take those disparagements to the bank.

And for thirteen years Pat Kirkwood would take those disparagements to the bank.

Years later Kirkwood said, “If we were as bad as everyone said we were, we wouldn’t have stayed open. If we killed eight to ten customers a night, or had twelve-year-old prostitutes sitting on bales of marijuana, we would have been shut down.

“We never broke any laws, but everybody would swear by all that was holy that we broke every law in the book. Well, I didn’t want to go around and deny it. Golly! It’d ruin the whole deal.”

Jimmy Hill, who managed the Cellar for eleven years, recalled, “Bad publicity was good for us, because evil was what we were built around.”

Jimmy Hill, who managed the Cellar for eleven years, recalled, “Bad publicity was good for us, because evil was what we were built around.”

Kirkwood carefully cultivated that aura of evil for the Cellar just as he cultivated a bifurcated persona for himself. He grew a beatnik beard, talked the hipster lingo, and often dressed in black. Cool cat. But he also appeared sinister. He carried a gun. He was tall and hollow cheeked. His eyes were dark and intense, as if he could bore holes with a stare.

A beatnik Beelzebub.

As the sixties became ever more freewheeling, the Cellar’s reputation became ever more wicked, making it a magnet for people who came, like pilgrims to a unholy shrine, in hope of seeing a fist fight or a real hippie or a naked woman. Wide-eyed college students sat around in the club and peered through the smoke at their fellow patrons. “That guy over there surely is a Hell’s Angel. And that guy has to be a banker. Uh oh. Is that guy over there an undercover vice cop? Hey, I think I’ve seen that waitress in a stag film.”

Kirkwood later said: “Where else could you come in for a dollar, stay from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., hear five different bands, watch the strippers, and take in all the weird people?”

What you would not take in at the Cellar were African-American patrons. African Americans were allowed in the Cellar only as musicians, such as Cannibal Jones (see below).

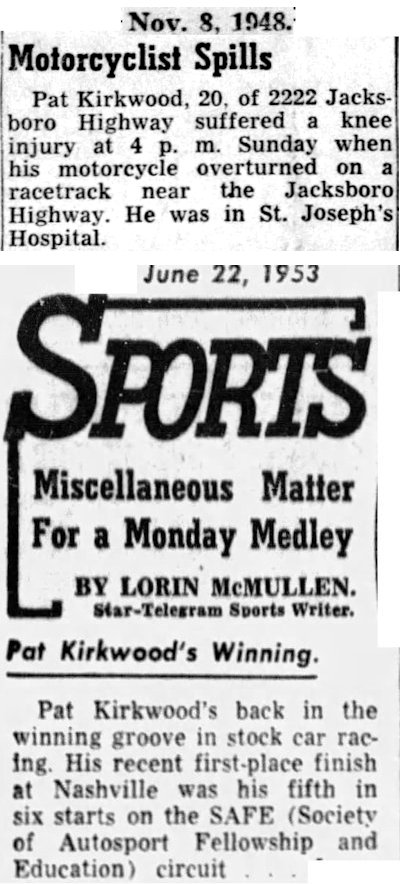

Pat Kirkwood was flamboyant, and he came by that flamboyance genetically. His father was W. C. (“Pappy”) Kirkwood, who for census purposes listed his occupation as “oil operator” but who at heart was a high-stakes gambler. Pappy owned the Four Deuces gambling casino at 2222 Jacksboro Highway. The Four Deuces, housed in a white stucco Spanish colonial-style mansion on a bluff overlooking the Highway to Hell, was also the Kirkwood family home. Pat’s mother Fay had been a rodeo rider in Gene Autry Rodeos and had produced all-cowgirl rodeos in the 1940s.

Pat Kirkwood was flamboyant, and he came by that flamboyance genetically. His father was W. C. (“Pappy”) Kirkwood, who for census purposes listed his occupation as “oil operator” but who at heart was a high-stakes gambler. Pappy owned the Four Deuces gambling casino at 2222 Jacksboro Highway. The Four Deuces, housed in a white stucco Spanish colonial-style mansion on a bluff overlooking the Highway to Hell, was also the Kirkwood family home. Pat’s mother Fay had been a rodeo rider in Gene Autry Rodeos and had produced all-cowgirl rodeos in the 1940s.

Pat Kirkwood was born in 1927 in a back room of the casino and grew up in the gambling environment. He later recalled his youth: “I thought everyone had a crap game in the front room.”

Associated Press writer Mike Cochran wrote in 1988 of Pat: “As a youngster growing up on Jacksboro Highway, Pat Kirkwood scrambled atop the roof of his dad’s gambling joint on Saturday nights and assessed the economy by activities along the road below. ‘If it was a three-ambulance evening, money was a little tight,’ he said. ‘But seven or eight ambulances meant everything was OK. People were out spending money and boozing and brawling.’”

Pat Kirkwood attended Paschal High School and in the 1950s was a stock car racer. He also did a little sailing and skin diving and claimed to be a uranium prospector.

Pat Kirkwood attended Paschal High School and in the 1950s was a stock car racer. He also did a little sailing and skin diving and claimed to be a uranium prospector.

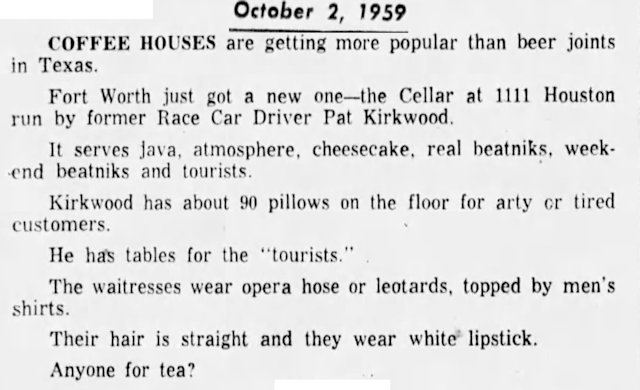

Kirkwood opened the Cellar in September 1959. The Star-Telegram noted that Cellar waitresses wore “opera house or leotards, topped by men’s shirts.” The coffeehouse’s location was fitting: in the south end of downtown where Hell’s Half Acre had been. The address, 1111 Houston Street, coincidentally was a halving of the 2222 address of the Four Deuces. At 1111 Houston Street, the Cellar could have been named the “Four Aces.”

Kirkwood opened the Cellar in September 1959. The Star-Telegram noted that Cellar waitresses wore “opera house or leotards, topped by men’s shirts.” The coffeehouse’s location was fitting: in the south end of downtown where Hell’s Half Acre had been. The address, 1111 Houston Street, coincidentally was a halving of the 2222 address of the Four Deuces. At 1111 Houston Street, the Cellar could have been named the “Four Aces.”

Kirkwood imposed only a few rules at the Cellar, but they were rigidly enforced: no drugs, no pimps, no underage customers, and no alcohol sales.

“We didn’t sell drinks,” he recalled, “but God knows we gave enough away [the VIP drink was Everclear grain alcohol—190 proof]: reporters, policemen, doctors, lawyers, musicians, entertainers, pretty girls, and my friends.”

In other words, Pat Kirkwood took care of those who could take care of him.

In 2000 he told Texas Monthly magazine what he had learned from his father at the Four Deuces about taking care of people: “Every year on Christmas Day one of my chores was passing out gifts to cops. If they were ‘harness bulls’ and wore regular uniforms, they got a bottle of whiskey. If they had stripes—corporals, sergeants, whatever—they got a turkey. If they had hardware—captains, for instance—they’d get a ham. There’d be twenty cars lined up. I’d be running in the house, taking things out, back and forth. I thought it was hard, boring work. And then I got to thinking about it: Pop was introducing them to me. Boy, did that pay off a thousand times in the Cellar days.”

Kirlwood recalled: “I utilized good management and administrative skills, but I let the patrons decide what the Cellar would be. I thought cool, Dave Brubeck-type, ‘Take Five’ jazz was what they’d want, but there was an immediate transition: Nobody wanted jazz. They wanted pop and rock.”

Many a musician used the Cellar stage as a stepping-stone: Shawn Phillips, Johnny Winter, John Denver, John Nitzinger, Bugs Henderson, Stevie and Jimmie Vaughan, Doug Sahm, Joe Ely, Johnny Nash, ZZ Top, and Poly High School graduate and evangelist-to-be Kenneth Copeland.

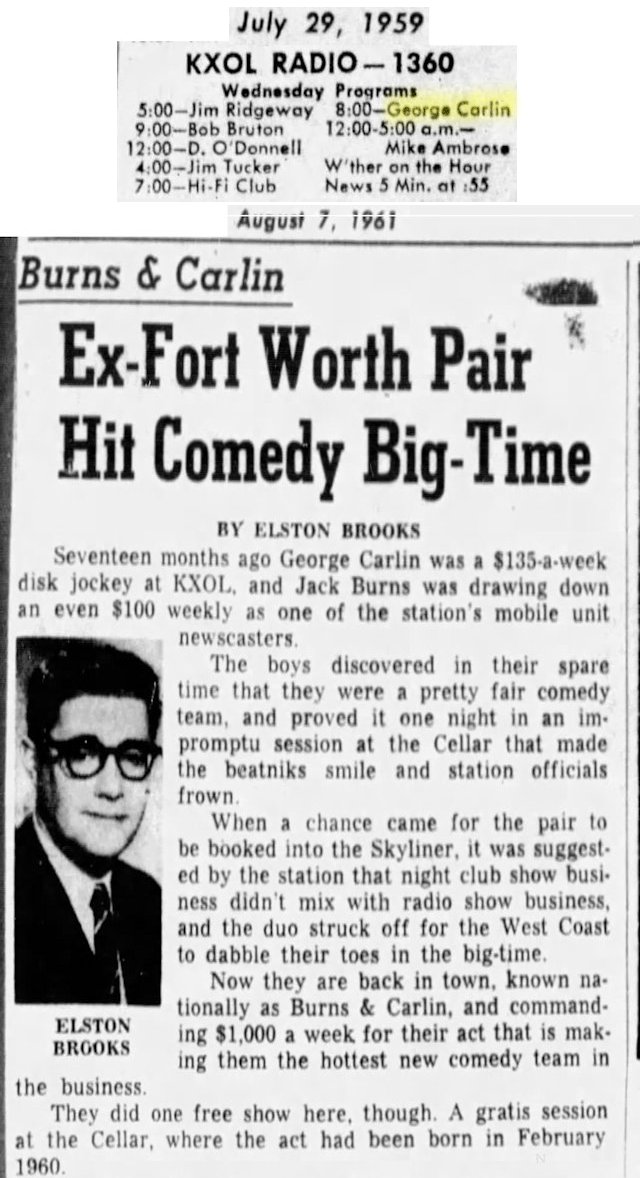

Elston Brooks in 1961 wrote that comedian George Carlin traced the beginning of his career to an impromptu performance with partner Jack Burns at the Cellar in 1960. Carlin was a DJ at radio station KXOL. Burns was a KXOL newscaster.

Elston Brooks in 1961 wrote that comedian George Carlin traced the beginning of his career to an impromptu performance with partner Jack Burns at the Cellar in 1960. Carlin was a DJ at radio station KXOL. Burns was a KXOL newscaster.

Cellar visitors over the years included Clint Eastwood, Lee Marvin, Johnny Cash, Jerry Van Dyke, and astronaut Alan Shepard.

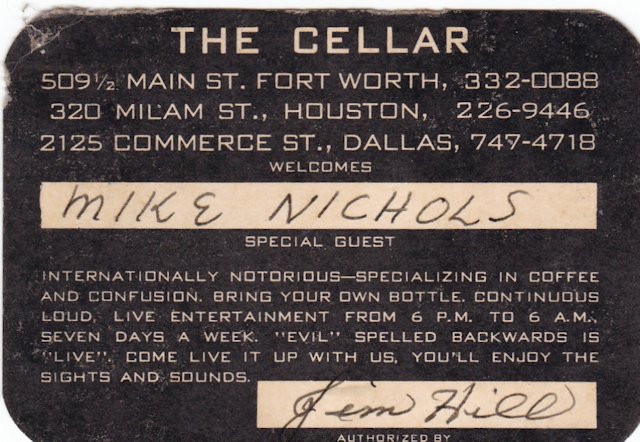

Kirkwood operated satellite Cellar clubs in Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio. The Fort Worth Cellar would have three different locations. As befits the lair of the beatnik Beelzebub, the Fort Worth Cellar for the first six years of its existence was located underground. Patrons descended via creaky stairs to an underworld den of eye-wateringly dense smoke and plaster-looseningly loud music.

In that setting the beatnik Beelzebub was indeed the prince of darkness: The Cellar had all the illumination of a coal mine. A black hole. Even the walls were black. Written on them in white: “You Must Be Weird Or You Wouldn’t Be Here” and “Evil spelled backwards is live.”

There were footprints on the ceiling.

Despite the live rock music, there was no space for patrons to dance. The floor was covered with tables and cushions. A two-foot-high, two-foot-wide footstage separated the stage from the seating area. The footstage was often used as a runway by waitresses who tossed caution—and clothes—to the wind.

Sometimes patrons, too, got caught up in the self-expression. Former Cellar house band musician Arvel Stricklin told the Star-Telegram’s Bud Kennedy about one night when two women patrons arrived wearing long coats.

The two women sat down in front of the band and unbuttoned their coats. Only the band members could see that the women were wearing only the long coats.

Refrigerator-sized bouncers kept the peace, kept out anyone who was not welcome, and keep the waitresses safe from the patrons.

Above the stage, visible to only the musicians, were three lightbulbs used as signals. The blue bulb signaled that police were on the premises. The red bulb signaled musicians to start playing immediately and continue until the light went out (the music would distract the audience from a fight). The white bulb signaled the all-clear.

When police entered the club, a spotlight was shined on a poster of Mickey Mouse on a wall, and the band began playing the theme music of TV’s Mickey Mouse Club program.

And police did enter the club. A lot.

During the Cellar’s first full year of operation—1960—the police department made 114 routine investigations at the Cellar. In 1961 Fort Worth police vice squad officer Oliver Ball called the Cellar a “public nuisance” and asked District Attorney Doug Crouch to investigate the Cellar for legal sanctions. By August 1961 police had visited the Cellar thirty-three times that year on complaints ranging from breaches of the peace to gang fights.

Ball said his office had received numerous complaints from parents that teenagers were using the Cellar as a hangout.

Kirkwood was piqued by that accusation.

“Man, like if all the young cats came here that said they did, we’d need a hole in the ground like with an H-bomb. These young cats are messing around some other place and moan to the home magistrates [parents] that they were digging at the Cellar.”

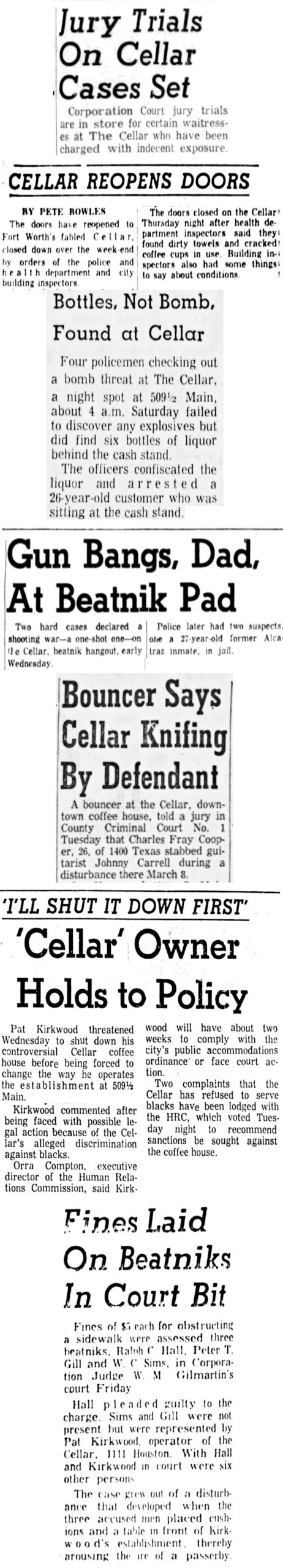

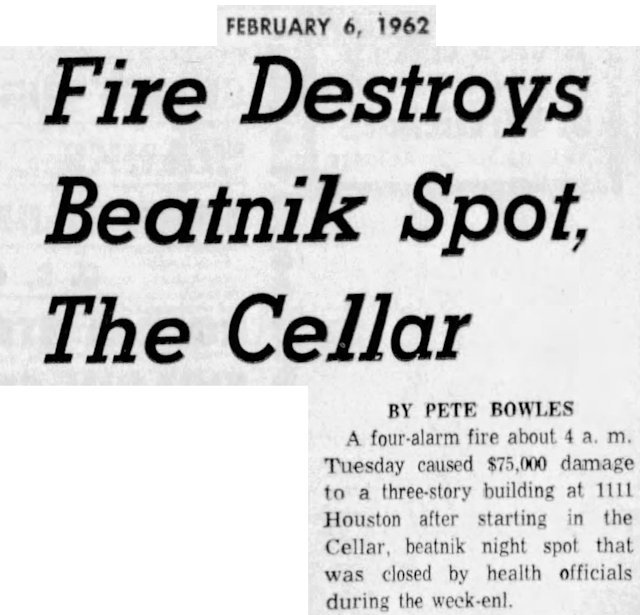

This sampler of newspaper clippings shows the major categories of violations by the Cellar (in descending order of frequency): indecent exposure, health department violations, liquor law violations, violence (fist fights, gunplay, knifings), racial discrimination, even vagrancy (patrons were playing chess on the sidewalk in front of the Cellar entrance).

This sampler of newspaper clippings shows the major categories of violations by the Cellar (in descending order of frequency): indecent exposure, health department violations, liquor law violations, violence (fist fights, gunplay, knifings), racial discrimination, even vagrancy (patrons were playing chess on the sidewalk in front of the Cellar entrance).

Such incidents generated hundreds of newspaper stories over thirteen years. Whereas most club owners displayed on a wall positive newspaper reviews of their club’s ambience or food or entertainment, Kirkwood displayed news reports about his club’s run-ins with the law.

Kirkwood subscribed to the adage attributed to P. T. Barnum: “All publicity is good publicity.” To Kirkwood even bad publicity about the Cellar was good because although publicity about violence and police raids and half-naked waitresses might repel one segment of society, it would attract another segment.

Some Cellar miscellany:

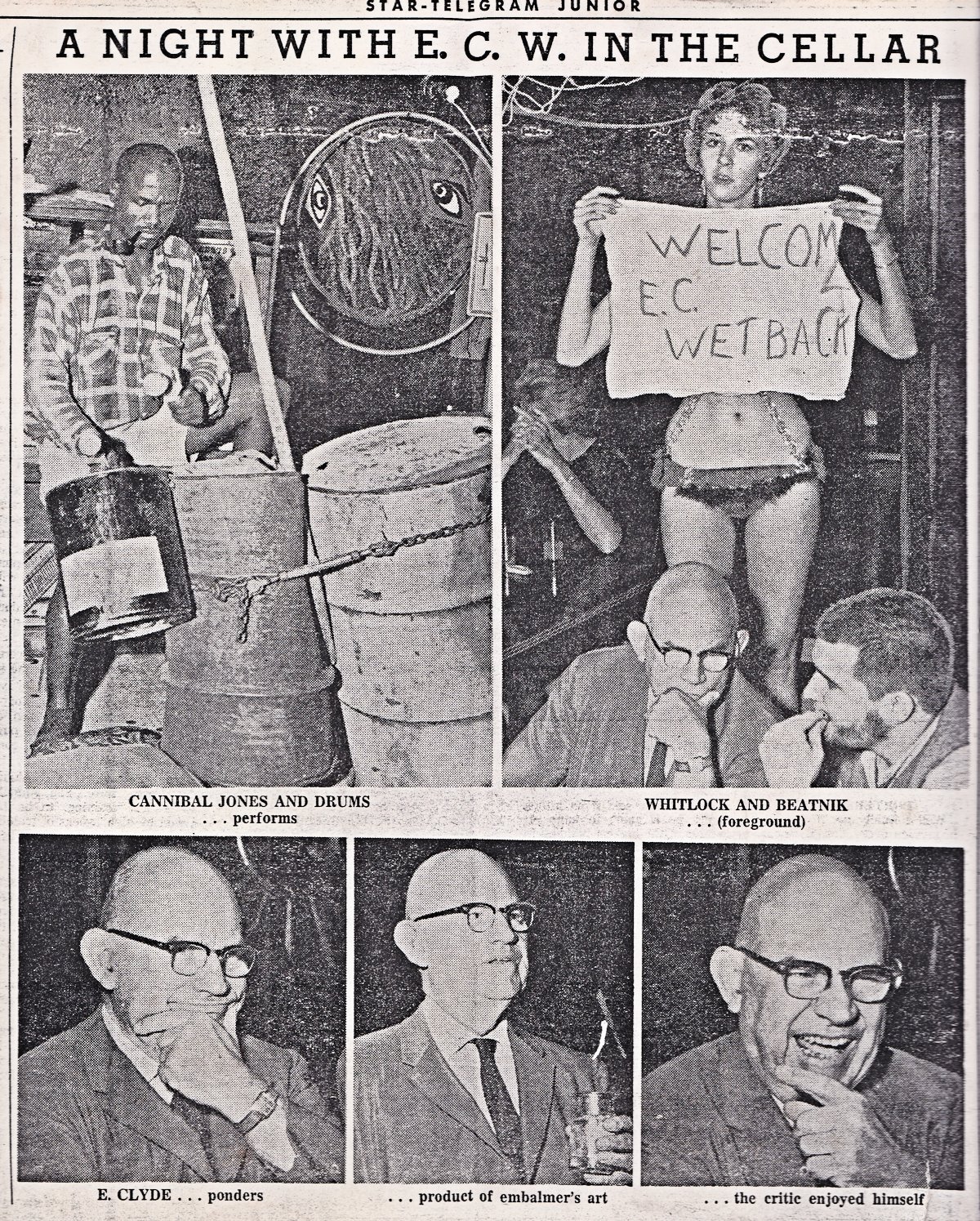

• In 1962 police reporter Bob Schieffer and a few other Star-Telegram employees cajoled Dr. E. Clyde Whitlock—a classically trained violinist, music teacher, and for forty-one years the newspaper’s music critic—into visiting the Cellar. With proper chaperonage, of course. Whitlock was as high-brow as his name sounded.

We can only guess which party was more bemused by the other: “E. C. Wetback” or the denizens of the Cellar. Whitlock later critiqued the Cellar in the Star-Telegram employee newsletter. He wrote that he “descended at midnight into that murky center of sybaritic hedonism, the Cellar, to observe the musical and terpsichorean arts as practiced there. . . .

We can only guess which party was more bemused by the other: “E. C. Wetback” or the denizens of the Cellar. Whitlock later critiqued the Cellar in the Star-Telegram employee newsletter. He wrote that he “descended at midnight into that murky center of sybaritic hedonism, the Cellar, to observe the musical and terpsichorean arts as practiced there. . . .

“The featured artist of this callithumpian cacophony is a burly mighty-muscled Negro by name of Cannibal Jones. His instruments are a steel oil barrel, a middle-sized oil drum, and a smaller powder can. The idea was to bang on these fortissimo and without termination, as accompaniment to a whistled solo of primitive melodic outline.

“But it was not so simple. These instruments must be tuned. This was accomplished with a wrecking bar, which on one end is pointed. Cannibal jabbed this savagely into the ends of his cans, thus changing the pitch. He seemed to have a notion of what sound he wanted, since after several lunges he was satisfied to go into his sonata.

“Each night he adds a few more holes, though it was said, not without a touch of nostalgia, that his present utensils of din have not yet attained that fine state of perforation and attuned concordance reached in his old battered set, which met dissolution in a recent fire in the old temple.

“The art of the dance is in nowise neglected. Going back to classic standards, there were shapely maidens, who gradually reduced their raiment to the costume of the classic Venuses carved by Phidias of old, and who added to their demonstrations sinuous contortions of the person.”

Mercy!

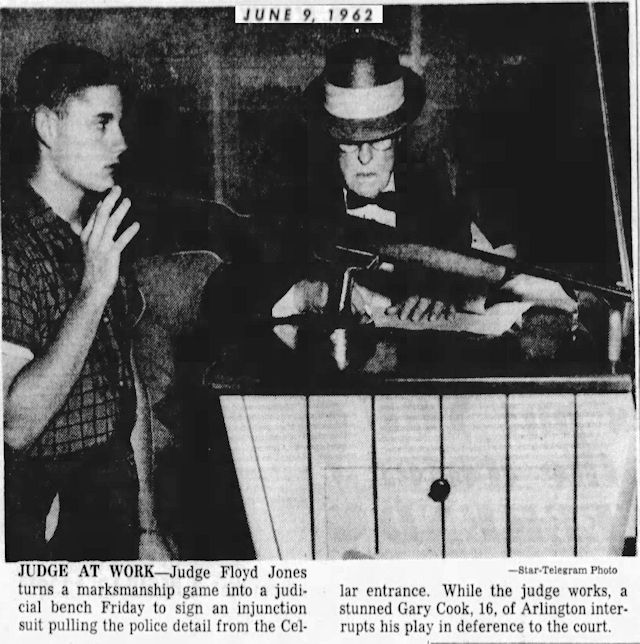

• Also in 1962 Kirkwood sought an injunction against Fort Worth police, who, he complained, were harassing his patrons by standing at the entrance to the Cellar and asking patrons for identification. The injunction was indeed granted—by a visiting judge from out of town who was scheduled to return to his hometown for the weekend by bus. But there was a fly in the espresso: The injunction was granted on a Friday but had not yet been signed by the judge. If the judge did not sign the injunction on Friday before he left town, he could not sign it until he returned the next Monday. Kirkwood wanted the injunction signed on Friday so it would be in effect before the Cellar’s heavy weekend patronage. Lawyers for both sides rushed to meet the departing judge at the Greyhound bus station. The judge signed the injunction, using the top of an arcade machine as his desk.

• Also in 1962 Kirkwood sought an injunction against Fort Worth police, who, he complained, were harassing his patrons by standing at the entrance to the Cellar and asking patrons for identification. The injunction was indeed granted—by a visiting judge from out of town who was scheduled to return to his hometown for the weekend by bus. But there was a fly in the espresso: The injunction was granted on a Friday but had not yet been signed by the judge. If the judge did not sign the injunction on Friday before he left town, he could not sign it until he returned the next Monday. Kirkwood wanted the injunction signed on Friday so it would be in effect before the Cellar’s heavy weekend patronage. Lawyers for both sides rushed to meet the departing judge at the Greyhound bus station. The judge signed the injunction, using the top of an arcade machine as his desk.

• The Cellar added to its colorful reputation in 1963 after Secret Service agents guarding President Kennedy on his fateful trip to Texas relaxed at the Cellar after hours and by some accounts—including Kirkwood’s—were served the Cellar’s VIP drink: Everclear grain alcohol. (The 1964 Warren Commission report concluded that the agents had not been drinking but conceded that they had committed a “breach of discipline.”)

More Cellar-JFK trivia: About three months before the Kennedy assassination, a man walked into Kirkwood’s Cellar in San Antonio and asked for a job. He washed dishes for two days, got paid, and disappeared. That man was Lee Harvey Oswald.

About six months before the assassination, Jack Ruby visited the Fort Worth Cellar to scout waitresses he wanted to hire as strippers at his Carousel Club in Dallas.

Among those Cellar waitresses Ruby hired was Karen (“Little Lynn”) Bennett, to whom Ruby wired money less than five minutes before he shot Oswald. She later was arrested for having a pistol in her purse as she entered the courtroom during Ruby’s trial. At the time, Little Lynn lived on Meadowbrook Drive in east Fort Worth.

Among those Cellar waitresses Ruby hired was Karen (“Little Lynn”) Bennett, to whom Ruby wired money less than five minutes before he shot Oswald. She later was arrested for having a pistol in her purse as she entered the courtroom during Ruby’s trial. At the time, Little Lynn lived on Meadowbrook Drive in east Fort Worth.

Tammi True, who waitressed at the Cellar and later danced at the Skyliner Ballroom on Jacksboro Highway and at Ruby’s Carousel Club, once was arrested for being a vagrant with no visible means of support. She showed up at her court appearance waving her tax return, which, she said, showed that she had more visible means of support than the judge.

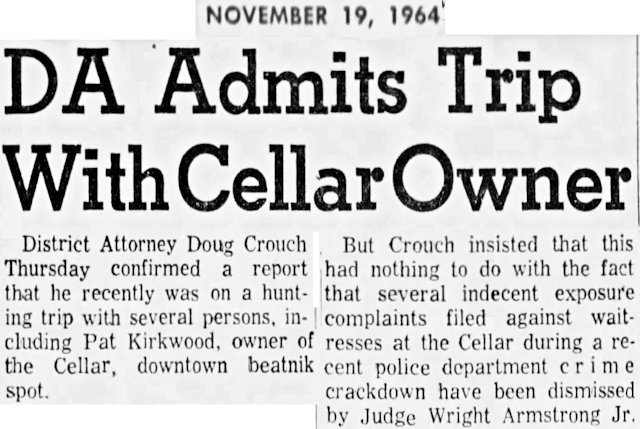

• Kirkwood alternately cursed and courted law enforcement officials. He bemoaned them when they raided and arrested and prosecuted in court. He befriended them to the point of taking them hunting with him. In 1964 District Attorney Crouch and three members of the police force went deer hunting with Kirkwood and his father. Crouch’s office had prosecuted both Kirkwoods many times. After the deer hunt made headlines, Crouch had a lot of ’splaining to do, especially after the DA’s office dropped several charges of indecent exposure against Cellar waitresses. Oh, and the three policemen were suspended from duty.

• Kirkwood alternately cursed and courted law enforcement officials. He bemoaned them when they raided and arrested and prosecuted in court. He befriended them to the point of taking them hunting with him. In 1964 District Attorney Crouch and three members of the police force went deer hunting with Kirkwood and his father. Crouch’s office had prosecuted both Kirkwoods many times. After the deer hunt made headlines, Crouch had a lot of ’splaining to do, especially after the DA’s office dropped several charges of indecent exposure against Cellar waitresses. Oh, and the three policemen were suspended from duty.

• In 1965, on July 4, Fort Worth police dispatchers were notified that a “gang fight” was raging on Goat Island in Lake Worth, where three hundred employees and patrons of the Cellar were holding their annual Independence Day celebration. Suddenly normally terrestrial Fort Worth police were faced with the need to organize a navy and mount a beach assault on Goat Island.

Taking part in the G-Day landing were seven police officers, two Lake Worth park officers, sheriff’s department officers, and three private citizens, all going ashore in two boats.

Turns out that G-Day was no mayday: The “gang fight” consisted of only two Cellar celebrants, who were arrested for fighting.

• One night a Cellar waitress noticed a piece of pipe lying on the floor of the club. She picked it up and yelled playfully to a nearby patron—a dentist: “Hey, Doc, look what I got!” Then she feigned a swing at the dentist with the pipe, it banged loudly, and pellets from a .410 shotgun shell peppered the dentist’s face. The dentist, terrified, stood up, pulled a .25-caliber pistol, and wildly fired six shots as people ducked and screamed. One patron was hit in the knee. The dentist took his leave and was later found hiding in a penny arcade around the corner. Turns out that the “pipe” was a zip gun kept on the premises in case of a robbery.

• Manager Jim Hill recalled: “Pat was always dreaming up stunts for getting into the papers. One day we took some unplucked chickens down to the duck pond in Trinity Park and built a fire, as if we were going to cook them. As Pat predicted, someone called the police and said, ‘Those beatniks are roasting the ducks!’ That made Page One.”

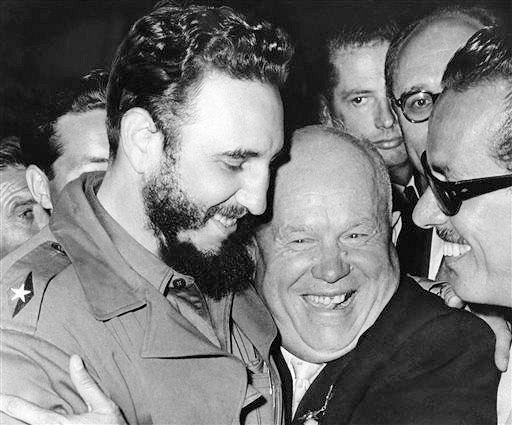

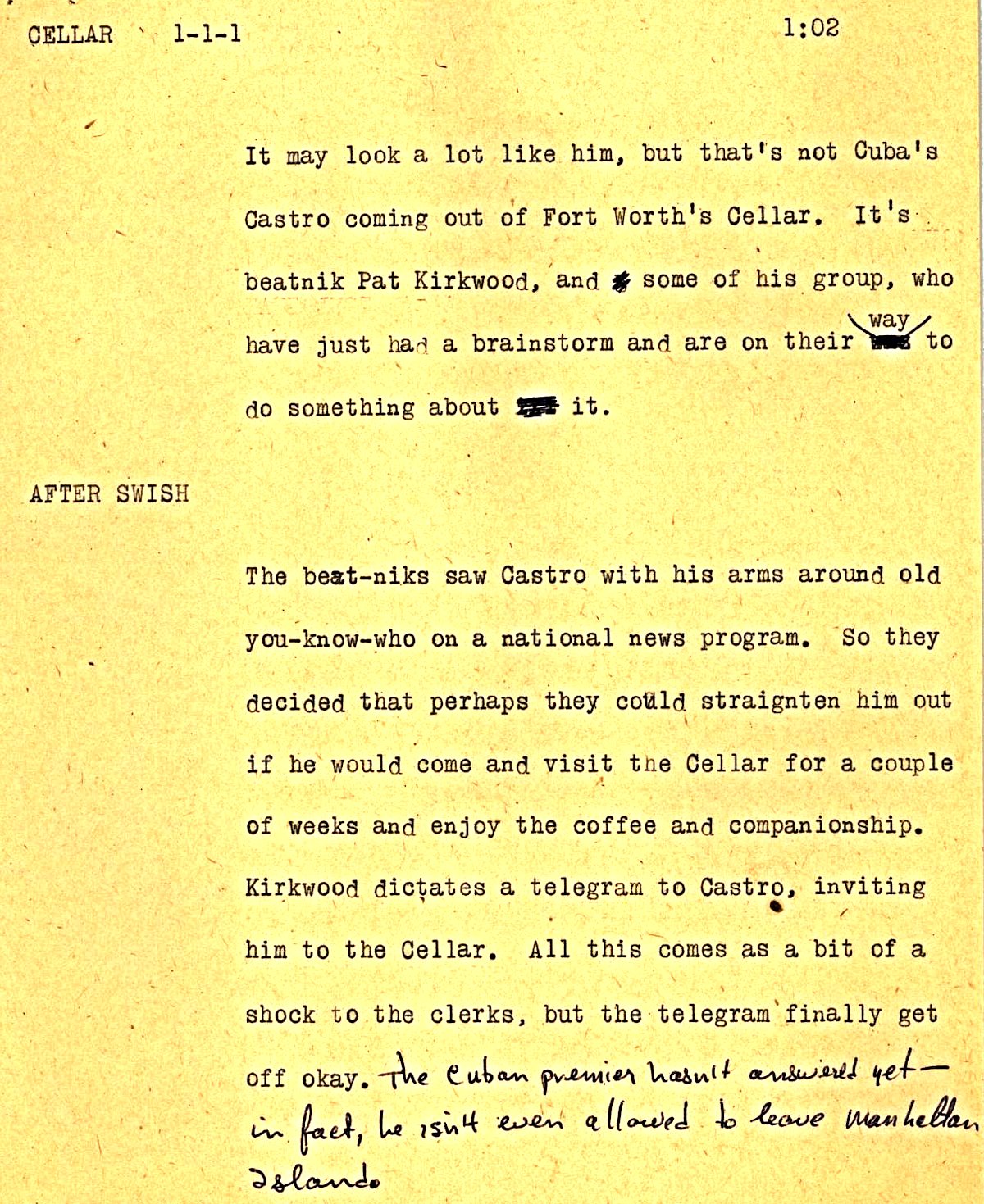

• In 1960 Cuba’s Fidel Castro and Russia’s Nikita Khrushchev attended the session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York City. As the WBAP TV Texas News script shows, Kirkwood saw a newspaper photo of the two Communists hugging and sent Castro a telegram inviting him to visit the Cellar to have a beard-to-beard tete-a-tete about Castro’s choice of friends. Alas, Kirkwood was told that Castro was not allowed to leave Manhattan Island. (Image from NBC 5/KXAS News Scripts, University of North Texas Special Collections.)

• In 1960 Cuba’s Fidel Castro and Russia’s Nikita Khrushchev attended the session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York City. As the WBAP TV Texas News script shows, Kirkwood saw a newspaper photo of the two Communists hugging and sent Castro a telegram inviting him to visit the Cellar to have a beard-to-beard tete-a-tete about Castro’s choice of friends. Alas, Kirkwood was told that Castro was not allowed to leave Manhattan Island. (Image from NBC 5/KXAS News Scripts, University of North Texas Special Collections.)

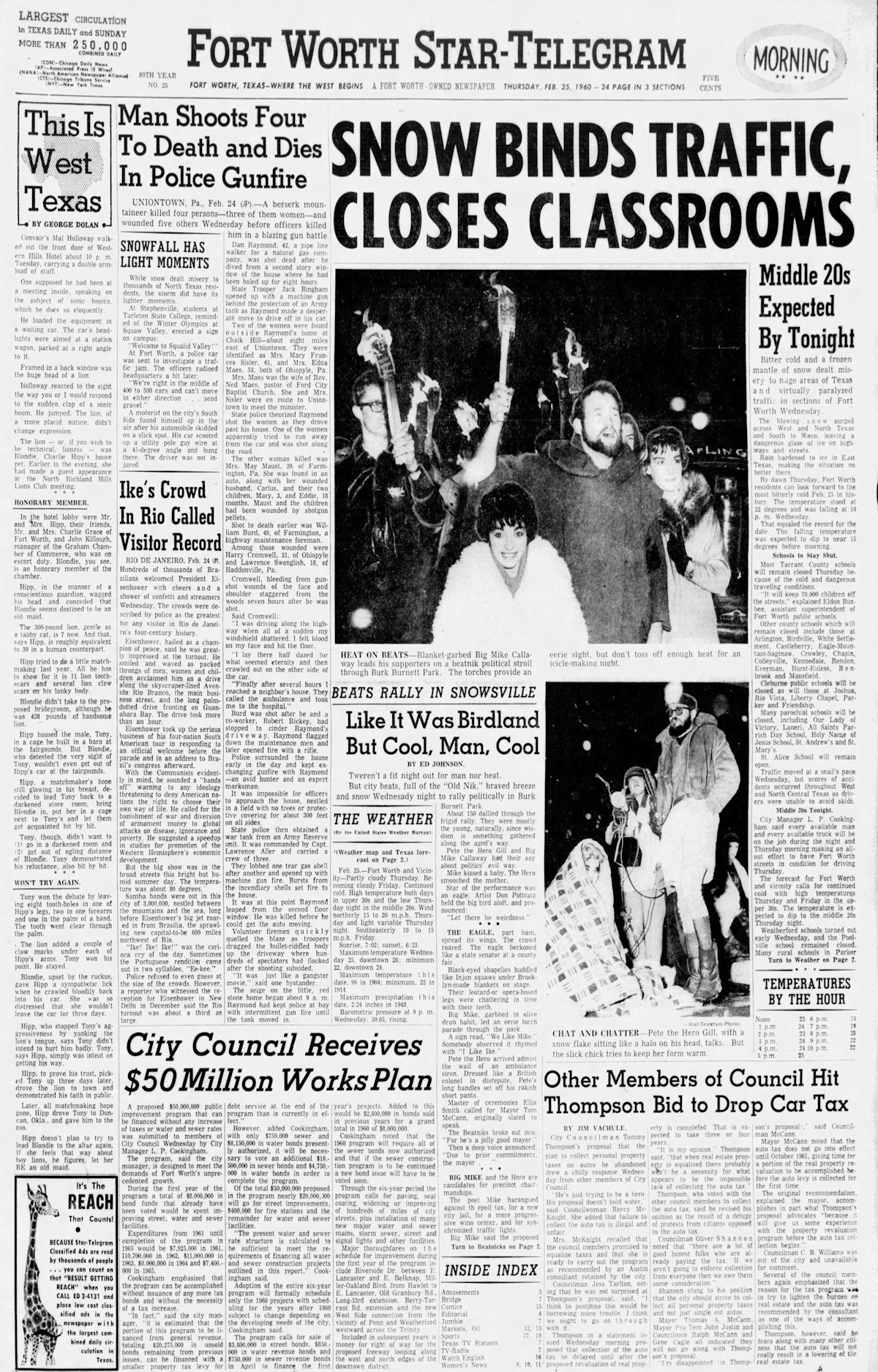

• The Cellar was Fort Worth’s unofficial press club. In 1960, Star-Telegram editor Phil Record recalled in 2001, “One night Kirkwood had been discussing the need for a new publicity stunt with some of the visiting journalists.

“‘Let’s run the Monk [Mike Callaway, a Cellar dweller; see Part 1] for Democratic precinct chairman,’ suggested someone, his reasoning undoubtedly blunted by Everclear. The Monk was a would-be poet who clothed himself in old Army blankets stitched together in the form of a monk’s clothing.

“Much to the dismay of Democratic Party officials, he signed up to run for chairmanship of the downtown precinct.

“Kirkwood decided to have a big rally in Burnett Park that would feature scantily clad dancing girls and a lion. (Kirkwood wanted to change the party’s symbol from a donkey to a more strong-hearted symbol.) This got the attention of the TV networks.

“The night of the park rally a snowstorm moved in. But the show went on, and the Cellar suddenly had a national reputation.”

The lion was a no-show, but an eagle stood in.

The lion was a no-show, but an eagle stood in.

Soon after that rally, Life magazine came to town to cover Fort Worth’s beatnik scene and published a photo feature (see Part 1), including this photo of the Cellar’s “Sam the Secret Weapon.” On the campaign poster for candidate Callaway, note the artist’s signature “Pack” (see Part 1).

Soon after that rally, Life magazine came to town to cover Fort Worth’s beatnik scene and published a photo feature (see Part 1), including this photo of the Cellar’s “Sam the Secret Weapon.” On the campaign poster for candidate Callaway, note the artist’s signature “Pack” (see Part 1).

• In January 1965 the Cellar went incognito to infiltrate the annual stock show parade. Most of the floats in the parade were, as usual, entered by riding clubs. Kirkwood filed the paperwork with parade organizers to enter a hay wagon in the parade. But rather than sign up as the Cellar, he signed up as “Fort Worth Bull Shippers Society.”

Not an eye was batted.

Kirkwood procured a wagon and two horses to pull it. As the parade got under way in forty-degree weather, the Bull Shippers wagon was peopled by cowboys and cowgirls wearing long coats. As the wagon passed the judges’ reviewing stand, the cowboys held up signs advertising the Cellar, and the cowgirls opened their coats to reveal bikinis and lingerie as 62,500 people (the male half of a crowd estimated at 125,000) cheered.

• Also in 1965, when the state began issuing vanity license plates, Kirkwood turned his Cadillac convertible into a rolling billboard with plates that read “CELLAR.”

• As a courtesy car for guests, the Cellar provided a Cadillac hearse.

A fire in 1962 forced the Cellar to move to a basement elsewhere in the old Acre—on 10th Street at Main.

A fire in 1962 forced the Cellar to move to a basement elsewhere in the old Acre—on 10th Street at Main.

In 1965 construction of the convention center forced the Cellar to move yet again. After six years in basements in the old Acre, the Cellar moved uptown and took a small step up from the underworld toward the light—to the second floor of 509 Main Street (where Mi Cocina is today). After the Cellar was upstairs and no longer in a cellar, Kirkwood refused to rename it the “Attic.” Instead, he said, he’d just hang his “Cellar” sign upside down.

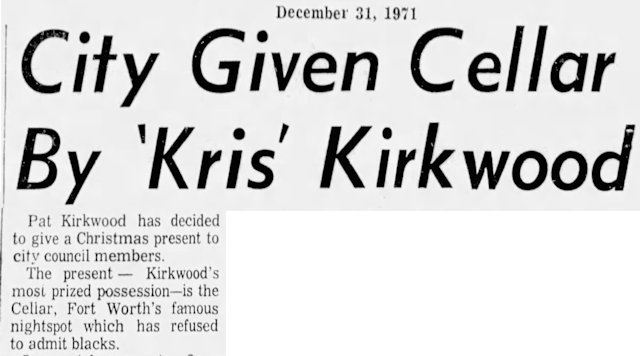

Fast-forward six years. In December 1971, after municipal court Judge Harold Valderas fined Kirkwood for refusing to allow African Americans into the Cellar, Kirkwood sent a letter to city hall giving the city the Cellar as a Christmas present. He signed the letter “Kris Kringle.” The city told Kirkwood that, in effect, it would prefer a fruitcake.

Fast-forward six years. In December 1971, after municipal court Judge Harold Valderas fined Kirkwood for refusing to allow African Americans into the Cellar, Kirkwood sent a letter to city hall giving the city the Cellar as a Christmas present. He signed the letter “Kris Kringle.” The city told Kirkwood that, in effect, it would prefer a fruitcake.

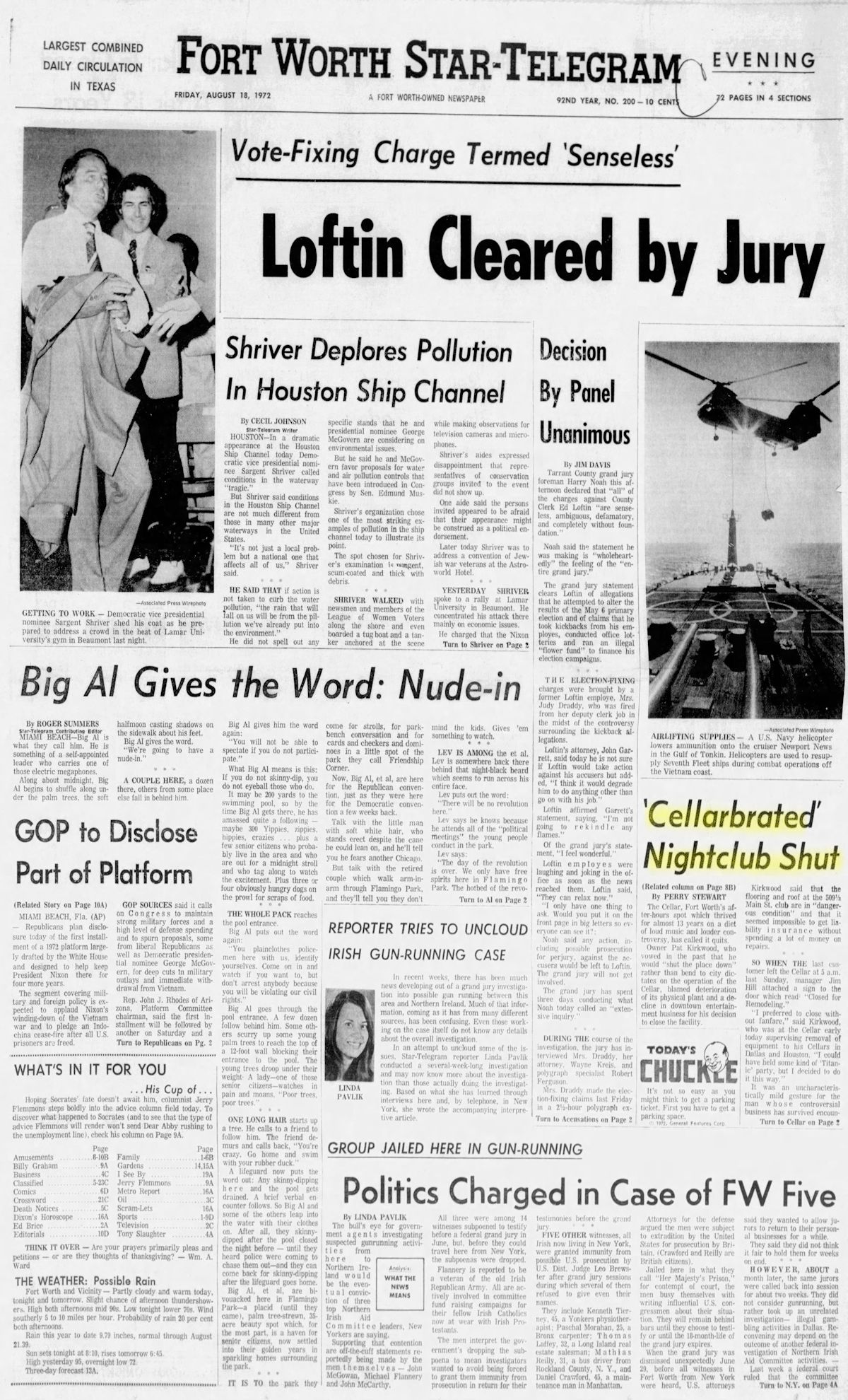

Eight months later Kirkwood closed the Cellar. He said the building that housed the Cellar had become structurally unsound. Because of that, he said, he faced a lose-lose situation: high insurance premiums or a high renovation bill. Neither option appealed to him. So, after thirteen years, Pat Kirkwood walked down those creaky stairs for the last time.

Eight months later Kirkwood closed the Cellar. He said the building that housed the Cellar had become structurally unsound. Because of that, he said, he faced a lose-lose situation: high insurance premiums or a high renovation bill. Neither option appealed to him. So, after thirteen years, Pat Kirkwood walked down those creaky stairs for the last time.

He moved to Granbury and went into the real estate business.

He moved to Granbury and went into the real estate business.

Real estate? Sounds frightfully mundane for the likes of the beatnik Beelzebub.

Maybe that’s why Kirkwood took a side job: helping to catch drug smugglers. Kirkwood had been trained as a pilot by another colorful character, Stormy Mangham. The U.S. Customs Service and the FBI enlisted Kirkwood as an informant. He flew his airplane for American and Mexican drug smugglers in sting operations. His code name reflected the fact that his hair was no longer black: “Mr. Silver.”

Kirkwood told AP’s Mike Cochran in 1997 that he was involved in dozens of smuggling cases that resulted in arrests and seizures of illicit drugs and money.

“The American government has made a lot of money off me,” Kirkwood said.

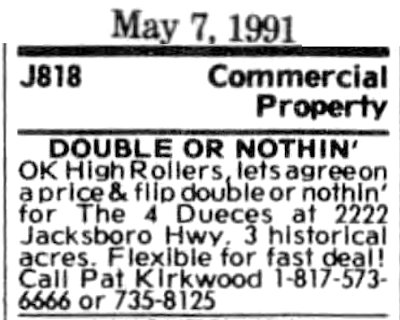

In 1991 Pat Kirkwood put his late father’s Four Deuces property on the market for $300,000. When he had no takers, in a gamble that surely would have made his father smile, Kirkwood sweetened the pot. “OK High Rollers,” his classified ad read, “let’s agree on a price & flip double or nothing for The 4 Deuces.” Alas, he again had no takers, and the Four Deuces was demolished despite a campaign to preserve it for its historical and architectural significance.

In 1991 Pat Kirkwood put his late father’s Four Deuces property on the market for $300,000. When he had no takers, in a gamble that surely would have made his father smile, Kirkwood sweetened the pot. “OK High Rollers,” his classified ad read, “let’s agree on a price & flip double or nothing for The 4 Deuces.” Alas, he again had no takers, and the Four Deuces was demolished despite a campaign to preserve it for its historical and architectural significance.

Ten years later, at age seventy-three, the beatnik Beelzebub died. But fifty years after the closing of the club that gave Fort Worth first coffee and then controversy, the legend seems well-nigh immortal.

Ten years later, at age seventy-three, the beatnik Beelzebub died. But fifty years after the closing of the club that gave Fort Worth first coffee and then controversy, the legend seems well-nigh immortal.

Watch Giles McCrary’s documentary film You Must Be Weird Or You Wouldn’t Be Here.

FW Legal Secretaries had an annual Bosses Banquet, and usually crowds would get together afterward to party a little longer. One night, the group I was with went to the Cellar, we were led to an area where we sat on large, dirty pillows, and served by a waitress who was very pregnant, wearing a bikini! Was fun and interesting but was glad when we left! Air was a lot fresher outside!

Boy, I’ll bet the air was fresh and the silence of the sidewalk deafening when you walked out.