Even a fire as sudden and sweeping as the fire that destroyed the Texas Spring Palace produces heroes.

We will never know the names of all the heroes of the fire of May 30, 1890, which took but one life out of about seven thousand people in attendance. But the names of some heroes we do know: Jack Jones, John Peter Smith, and Zeno Ross, Jesse Williams, even Russell Harrison, son of President Harrison.

And, of course, Al Hayne, the only fatality.

And another known hero was, more properly, a heroine.

And only fifteen years old.

Ada Elizabeth Large was born in Chicago in 1874. Her family moved to Fort Worth, where in 1885 she was promoted from third grade to fourth grade at Building 5, which was in the Third Ward.

Ada Elizabeth Large was born in Chicago in 1874. Her family moved to Fort Worth, where in 1885 she was promoted from third grade to fourth grade at Building 5, which was in the Third Ward.

Her father William was a carpenter. The Larges lived on Cochran Street, which no longer exists, on the near South Side about five blocks from where the Texas Spring Palace would stand.

Her father William was a carpenter. The Larges lived on Cochran Street, which no longer exists, on the near South Side about five blocks from where the Texas Spring Palace would stand.

In 1888 Ada, then about fourteen, was a member of the junior preparatory department of Texas Wesleyan College on Cannon Street (today the site of Green B. Trimble Technical High School).

In 1888 Ada, then about fourteen, was a member of the junior preparatory department of Texas Wesleyan College on Cannon Street (today the site of Green B. Trimble Technical High School).

Fast-forward to 1890. The Texas Spring Palace exhibition was in its second season. For the Larges, the exhibition was a family affair. As a carpenter, William Large had helped to build the massive wooden building. Mrs. Large was a leader of the floral committee that helped to decorate the building. And Ada helped her mother.

Fast-forward to 1890. The Texas Spring Palace exhibition was in its second season. For the Larges, the exhibition was a family affair. As a carpenter, William Large had helped to build the massive wooden building. Mrs. Large was a leader of the floral committee that helped to decorate the building. And Ada helped her mother.

By the night of May 30 Ada been in the palace many times and knew its layout well when the fire broke out.

The fire was reported around the country and in the United Kingdom.

The fire was reported around the country and in the United Kingdom.

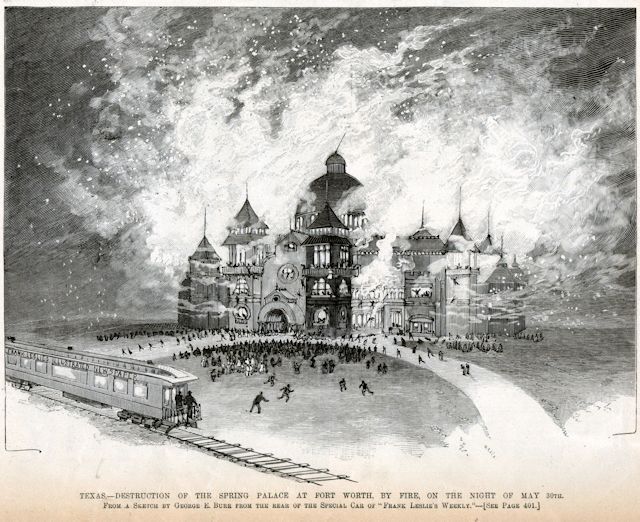

Journalists of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper were touring the South in a special railroad car and happened to be covering the Texas Spring Palace exhibition that night. A Leslie’s artist captured this scene from the railroad car parked on a track of the Texas & Pacific railroad reservation.

Journalists of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper were touring the South in a special railroad car and happened to be covering the Texas Spring Palace exhibition that night. A Leslie’s artist captured this scene from the railroad car parked on a track of the Texas & Pacific railroad reservation.

Ada’s heroism during the fire was not made public until November.

Ada’s heroism during the fire was not made public until November.

The Gazette wrote: “On that awful night . . . when the cry of fire rang through the Spring Palace, . . . Miss Ada was near the floral display. Looking up into the dome she perceived the cause of the panic and saw also the necessity for instant action. Not selfishly seeking to make secure her own flight, she cast about for any unfortunates who might need succor, and perceiving the numbers of children playing about, set herself to providing their safety. . . . Not until every living thing had left the palace, not until her own clothing had been burned and torn to shreds and her skin in places was parched and blistered, could she be induced to leave. And then it was only by strenuous urging that she was got from the building by Capt. B. B. Paddock and others.

“But she did not stop there. On all hands were people wounded and suffering, receiving surgical attention as fast as the small force of surgeons at hand could afford it. Lint and other such articles were in demand. With but scant clothing and herself suffering terribly from wounds and burns, Miss Ada sped to her home and brought the necessary articles, thus aiding in the work of helping the wounded.”

For her heroism the directors of the exhibition presented Ada with a gold medal. The inscription on the medal read: “Presented by the Directors of the Texas Spring Palace for Heroic Conduct Displayed at the Burning of Their Building May 30, 1890.”

With the medal was included $25 ($700 today) in gold “as further testimony of appreciation of her heroism and to repay in part her loss of clothing on the occasion of her noble conduct.”

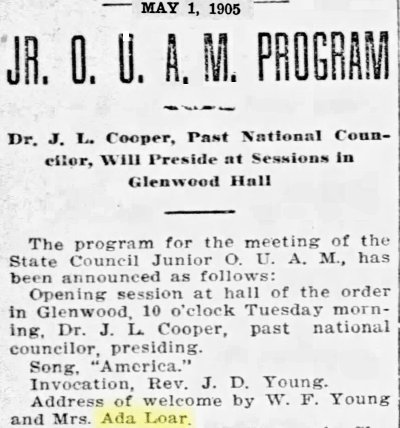

Fast-forward fifteen years. Ada was thirty years old, a member of the State Council Junior Union of American Mechanics, a fraternal order with a hall in Glenwood. She also was a wife and a mother: Ada had married Silvanin R. Loar in Chicago in 1895. Ada and Silvanin had a daughter, Marion Alice, in 1896. Soon after, Ada moved back to Fort Worth with her family. Silvanin died in 1908. About 1909 Ada married William M. Mustard, who worked at Hub Furniture Company in Glenwood. Ada and William lived on Stella Street five blocks from Hub and one block from the “last rebel,” who also worked at Hub.

Fast-forward fifteen years. Ada was thirty years old, a member of the State Council Junior Union of American Mechanics, a fraternal order with a hall in Glenwood. She also was a wife and a mother: Ada had married Silvanin R. Loar in Chicago in 1895. Ada and Silvanin had a daughter, Marion Alice, in 1896. Soon after, Ada moved back to Fort Worth with her family. Silvanin died in 1908. About 1909 Ada married William M. Mustard, who worked at Hub Furniture Company in Glenwood. Ada and William lived on Stella Street five blocks from Hub and one block from the “last rebel,” who also worked at Hub.

In 1915 Washer brothers department store commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Texas Spring Palace fire with a window display that included Ada’s gold medal, “the torn and scorched fragments of a white waist [blouse] worn by Miss Large on the occasion,” and photos of her, the palace, and its exhibits.

In 1915 Washer brothers department store commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Texas Spring Palace fire with a window display that included Ada’s gold medal, “the torn and scorched fragments of a white waist [blouse] worn by Miss Large on the occasion,” and photos of her, the palace, and its exhibits.

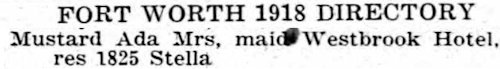

In 1918 Ada was a maid at the Westbrook Hotel and still living on Stella Street in Glenwood.

In 1918 Ada was a maid at the Westbrook Hotel and still living on Stella Street in Glenwood.

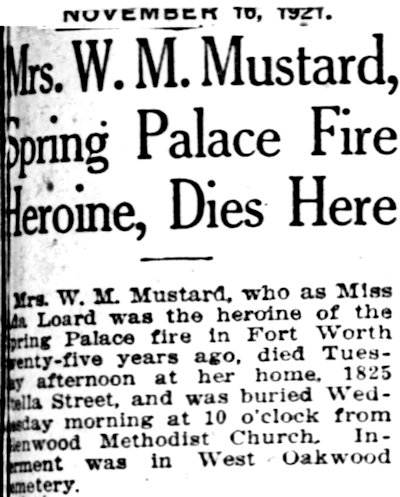

Ada died in 1921. She is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

Ada died in 1921. She is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

Ada Large Loar Mustard’s daughter Marion Alice Loar Hardin died in 1985—ninety-five years after the Texas Spring Palace fire of 1890. Many times the fire’s youngest heroine had told the story of “that awful night” to her daughter, who in turn told it to her daughter in the next century.

Ada Large Loar Mustard’s daughter Marion Alice Loar Hardin died in 1985—ninety-five years after the Texas Spring Palace fire of 1890. Many times the fire’s youngest heroine had told the story of “that awful night” to her daughter, who in turn told it to her daughter in the next century.

Posts About Women in Fort Worth History