Early in the twentieth century the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor welcomed immigrants with the promise of “Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” as they approached Ellis Island. Likewise, during the Great Depression Bridget (“Bridie”) O’Driscoll, who herself had twice immigrated to America, welcomed the tired, the poor, the huddled into her sanctuary on Fort Worth’s North Side.

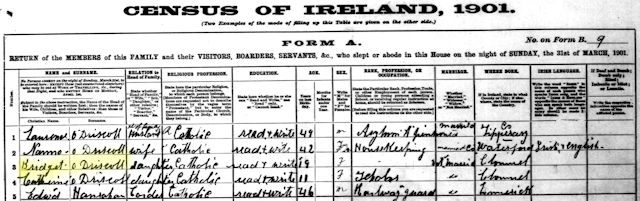

Bridie O’Driscoll was born in 1881 in Clonmel, Ireland (lower right corner), twenty miles from Tipperary. As she grew up, Clonmel was a tiny village in an agrarian area that even today reminds us why Ireland is called the “Emerald Isle.”

Bridie O’Driscoll was born in 1881 in Clonmel, Ireland (lower right corner), twenty miles from Tipperary. As she grew up, Clonmel was a tiny village in an agrarian area that even today reminds us why Ireland is called the “Emerald Isle.”

As a teenager Bridie was known as a dancer. She had even won first prize—a golden shamrock—in a dance contest. In 1901 at age nineteen Bridie O’Driscoll packed her golden shamrock and her dreams of becoming a professional dancer and sailed to New York, passing the Statue of Liberty and landing at Ellis Island on June 15.

As a teenager Bridie was known as a dancer. She had even won first prize—a golden shamrock—in a dance contest. In 1901 at age nineteen Bridie O’Driscoll packed her golden shamrock and her dreams of becoming a professional dancer and sailed to New York, passing the Statue of Liberty and landing at Ellis Island on June 15.

Bridie stayed with a sister and brother-in-law in lower Manhattan. There were hundreds of Bridie O’Driscolls in New York aspiring to be professional dancers. Most failed. But this one succeeded. Her grandson, Jim Pitts of Fort Worth, said Bridie became a chorus girl, dancing in several Broadway musicals.

Pitts said: “She was finally hired by the late Flo Ziegfeld to dance in his famous Ziegfeld Follies in 1905.”

Talent aside, Bridie also had the “look” of her era. That’s Bridie on the left in 1905. On the right is Evelyn Nesbit in 1901. As a Gibson Girl model, Nesbit was the epitome of feminine beauty. Nesbit became bored with modeling and, like Bridie, became a Broadway chorus line dancer. Nesbit later became an actress and then one corner of a fatal love triangle. (Photos from Jim Pitts and Wikipedia.)

Early in the twentieth century dancing on the stage was considered an unseemly occupation for a nice Catholic girl, Pitts said, so Bridie told her sister that she worked nights in a chocolate factory.

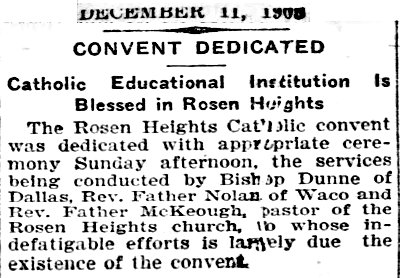

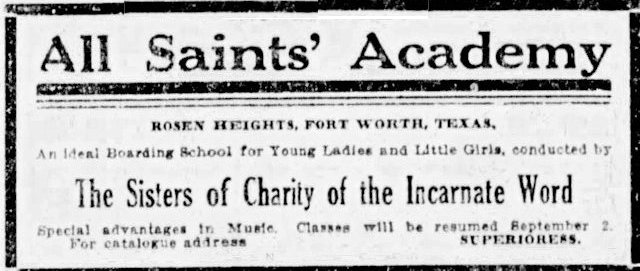

As Bridie O’Driscoll danced on Broadway, and the girl from an Irish village adjusted to life in an American city of four million people, fourteen hundred miles away, Sam Rosen, godfather of the North Side, gave the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word land on Belle Avenue (near today’s North Side High School) on which to build their All Saints Academy, a convent and girls boarding school. (The sisters also operated St. Joseph Infirmary.) The Belle Avenue facility was dedicated in December 1905 by Bishop Edward J. Dunne (as in the Dallas high school) and Father Robert Nolan (as in the Fort Worth high school).

As Bridie O’Driscoll danced on Broadway, and the girl from an Irish village adjusted to life in an American city of four million people, fourteen hundred miles away, Sam Rosen, godfather of the North Side, gave the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word land on Belle Avenue (near today’s North Side High School) on which to build their All Saints Academy, a convent and girls boarding school. (The sisters also operated St. Joseph Infirmary.) The Belle Avenue facility was dedicated in December 1905 by Bishop Edward J. Dunne (as in the Dallas high school) and Father Robert Nolan (as in the Fort Worth high school).

Meanwhile back in New York, with time Bridie realized that in the city of “If you can make it here, you can make it anywhere,” most don’t make it. She would never rise above the level of chorus line dancer. She would never be a Broadway star. So, about 1910 she again packed her shiny shamrock—and her tarnished dreams—and returned to the village of Clonmel. There she married George Ottley, her longtime sweetheart. Bridie and George had a daughter, Josie.

But life was hard in Ireland, and in 1916 George immigrated to America and found work in Texas.

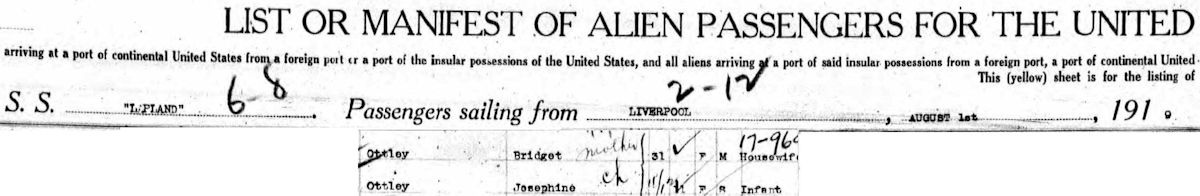

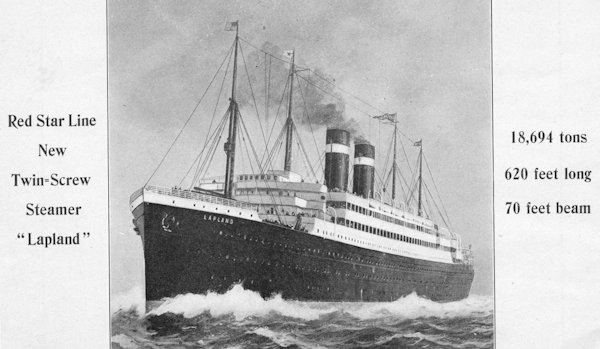

In 1919 George sent for Bridie and Josie. Mother and daughter sailed from Liverpool with other immigrants from the United Kingdom on the Belfast-built steamer S.S. Lapland. For the second time Bridie passed Lady Liberty in New York Harbor and landed at Ellis Island. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 1919 George sent for Bridie and Josie. Mother and daughter sailed from Liverpool with other immigrants from the United Kingdom on the Belfast-built steamer S.S. Lapland. For the second time Bridie passed Lady Liberty in New York Harbor and landed at Ellis Island. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

George Ottley was working for Humble Refining Company in Iowa Park near Wichita Falls.

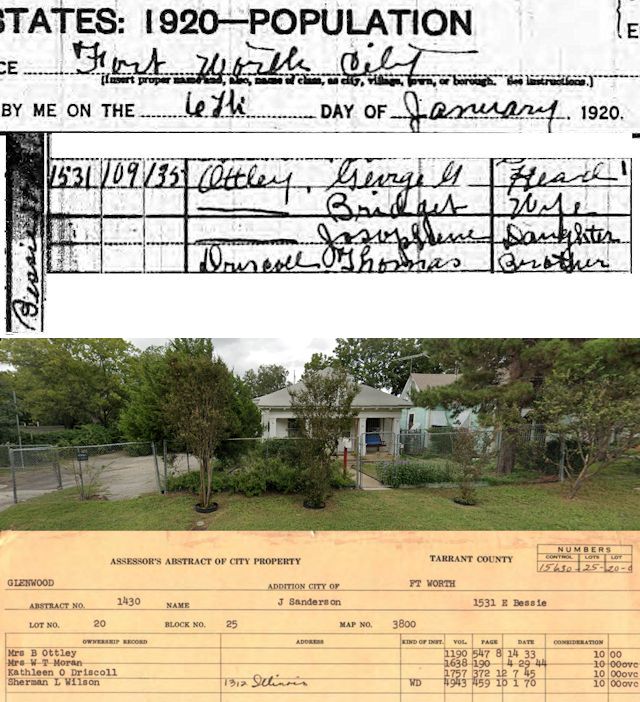

But in 1920 George was laid off. Bridie’s sister—Sister Villanova Mary O’Driscoll—was principal of All Saints Academy on the North Side. She encouraged the Ottleys to move to Fort Worth. Bridie’s brother Tom, a miner in Nevada, bought the Ottleys a house at 1531 Bessie Street in Glenwood.

But in 1920 George was laid off. Bridie’s sister—Sister Villanova Mary O’Driscoll—was principal of All Saints Academy on the North Side. She encouraged the Ottleys to move to Fort Worth. Bridie’s brother Tom, a miner in Nevada, bought the Ottleys a house at 1531 Bessie Street in Glenwood.

George soon got a job as a dispatcher for the Fort Worth & Denver railroad, and Bridie and George had their second child, Anna.

The Ottleys attended St. Patrick Catholic Church, whose Father Robert Nolan had participated in the dedication of All Saints Academy in 1905. Daughter Josie attended school at the academy, where her aunt was principal.

But by 1925 All Saints Academy was losing enrollment to other parochial schools. The sisters closed the academy. But they hoped to reopen it eventually, so, the nuns, led by Sister Villanova Mary O’Driscoll, asked the Ottleys to move into the building as caretakers. The Ottleys rented their Bessie Street house and moved into the academy building in 1927.

The Ottleys converted part of the building into living space for a family.

The Great Depression began in 1929 and eventually caught up with even normally booming Cowtown.

And that’s when the Sisters of Charity discovered that Sister Villanova’s sister had become a sister of charity in her own right. Bridie’s grandson Jim Pitts said, “The ex-New York chorus girl welcomed any and all who knocked at the door.”

Just like Lady Liberty in New York Harbor.

Victims of the Depression—out of a job, out of a home, out of food—began to show up at the Ottleys’ door asking for, Pitts said, “a sandwich, a cup of coffee, a dime . . . or a place to stay.”

Bridie Ottley, with four mouths of her own to feed, didn’t have a lot to spare. And husband George Ottley did not welcome people he considered to be freeloaders.

But Bridie’s heart—like her shamrock—was gold. She took in all who needed a meal or a bed. No checkout time.

She told her residents: “All Saints is a clean, dry place where the rent never comes due.”

Daughter Josie told the Star-Telegram in 2002, “Everyone living at All Saints was looking for work. . . . None of the residents received aid from any public or charitable source. My mother kept a coffee can at the foot of the stairs, and residents voluntarily dropped in pocket change when they could to help pay the utility bills and buy coal for the winters.”

Josie said she never knew of anyone stealing from the can.

One economic refugee, a widower with three sons, had been a well-to-do oilman with a fine home and all the trappings of wealth. Then the crash of 1929 made the rich man a poor man. Bridie took in father and sons.

A cowboy and his wife showed up with chickens and a small dairy herd. Birdie put the couple under the roof and the animals out back, where they provided the residents with meat, eggs, milk, and butter.

There were always single mothers with children. Some mothers had been abandoned by their husband; others were living single as their husband was forced to leave town to find work.

The Lady Liberty of Rosen Heights welcomed them all.

She took in an ex-convict with no last name and the owners of a nearby speakeasy after their building burned down.

Some residents, such as the cowboy, found outdoor work: shoveling manure at the stockyards, unloading railroad cars, picking cotton.

Others found indoor work: keeping books, clerking at stores.

Those who found occasional work on the North Side could walk to their job. Those who found jobs farther afield, such as downtown, rode Sam Rosen’s streetcar line.

When the other adults went to work, Bridie Ottley took care of their children. The school-age children attended nearby Rosen Heights Elementary School or Mount Carmel Academy.

Daughter Josie recalled in 2002: “Usually residents took care of obtaining their own food and cooking their meals. Whenever they had as much as five dollars, they would go downtown to the Jones Street Farmers’ Market and come home with a carload of produce.”

The Ottley children, Josie and Anna, grew a vegetable garden out back.

“Almost every family in those days raised homegrown vegetables and fruit,” Josie recalled.

“Some of the women did canning under the supervision of” the cowboy’s wife, Josie said. “All these items could be stored in the pantries in the large basement kitchen.”

Josie recalled that after church on Sundays the women chopped vegetables, sifted flour, made pie dough, and baked.

For the children there was playground equipment left over from the academy. For Saturday nights there was a wind-up Victrola.

Grandson Jim Pitts said the men of Bridie’s sanctuary ran a poker parlor in the nuns’ dormitory and made bootleg whiskey in a still in the basement.

“Let’s not judge those whose sins differ from our own,” Bridie told her priest, Father Nolan.

The Ottleys were Catholic, and Bridie occasionally took in children from Dallas’s Catholic Bishop Dunne orphanage when it became overcrowded. But Bridie welcomed people of any—or no—religion. Jim Pitts said the Catholic Lady Liberty once consulted with Sam Rosen, the Jewish godfather of the North Side, about dietary restrictions for two homeless Jewish boys at the convent.

The sanctuary operated on the thinnest margin of solvency. Daughter Josie told the Star-Telegram in 2002: “Often when Bridie was short of money, she’d pawn her gold shamrock won in that dance contest in Clonmel” to buy food, coal, and other essentials.

“Her brother, Tom O’Driscoll, the gold and siver miner in Nevada, periodically would send her a letter and enclose some money. The shamrock was in the pawn shop one time, and she couldn’t retrieve it until she received one of Tom’s money letters.”

One day, grandson Jim Pitts said, a young prostitute who called Bridie “Mom” checked out of the sanctuary, and the shamrock was never seen again.

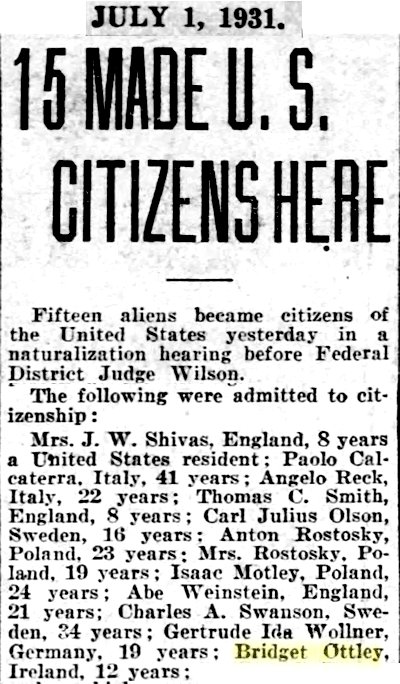

Bridie O’Driscoll Ottley became a U.S. citizen in 1931.

Bridie O’Driscoll Ottley became a U.S. citizen in 1931.

Built as a convent and boarding school, the building, at two and a half stories, could accommodate a lot of refugees. The population of Bridie’s sanctuary at times surpassed thirty people, perhaps half of them children. After the nuns’ sleeping quarters and the boarding school were populated, Bridie assigned each family to a classroom. (Photo from Jim Pitts.)

Built as a convent and boarding school, the building, at two and a half stories, could accommodate a lot of refugees. The population of Bridie’s sanctuary at times surpassed thirty people, perhaps half of them children. After the nuns’ sleeping quarters and the boarding school were populated, Bridie assigned each family to a classroom. (Photo from Jim Pitts.)

But as the economy recovered, the residents of Bridie’s sanctuary began to find permanent jobs. As they got back onto their financial feet, they said goodbye to Lady Liberty and her sanctuary.

In 1935 the Ottleys, too, moved out and returned to their Bessie Street home in Glenwood.

All Saints Academy never reopened.

After the Ottleys moved out, Shield of Faith Bible Institute moved in. The building later would house other religious institutions and finally became an apartment house.

After the Ottleys moved out, Shield of Faith Bible Institute moved in. The building later would house other religious institutions and finally became an apartment house.

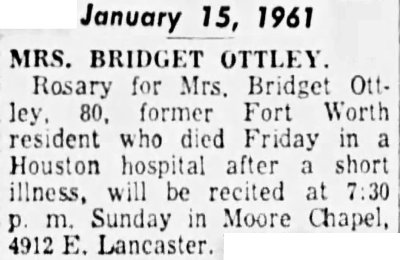

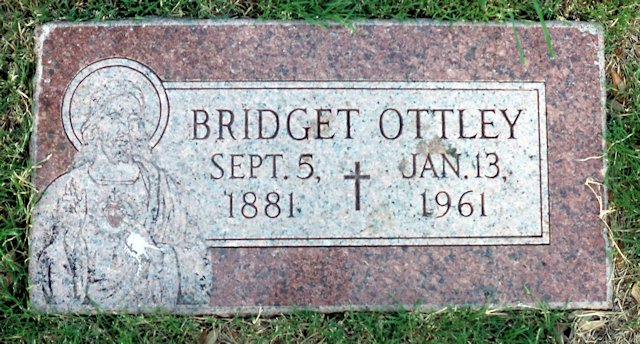

Bridget O’Driscoll Ottley, the Lady Liberty of Rosen Heights, died in 1961 and is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Bridget O’Driscoll Ottley, the Lady Liberty of Rosen Heights, died in 1961 and is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

She did not live to see her sanctuary demolished to make way for a Masonic lodge hall.

She did not live to see her sanctuary demolished to make way for a Masonic lodge hall.

(Thanks and a tip o’ the paddy cap to Jim Pitts for his help. He has written a book—The Last Shamrock: A Novel of the Great Depression—about his grandmother.)

Posts About Women in Fort Worth History

Thanks so much, Mike, for this wonderfully told and thorough story about my grandmother, Bridie, the Lady Liberty of Rosen Heights. Amazed by your in depth research, picture of the ship she sailed aboard to New York, the account of her dancing days on Broadway. I’m’ stunned by the likeness of Bridie and the other Gibson girl, Evelyn Nesbitt, news clips about Bridie’s obtaining citizenship in Fort Worth and her obituary, pictures of her home (still occupied) at 1531 Bessie Street in Fort Worth. Simply amazing: even census records from Ireland and the U.S. And more. This is the real story behind my novel, “The Last Shamrock.” You’re a gifted storyteller, Mike.

And thank you, Jim, for giving me an annual St. Patrick’s Day post. You were right to write a novel about your grandmother.