She was, as Mark Twain would say, “just full of sand.”

Grit.

That grit would make her perhaps Fort Worth’s first woman millionaire (as counted in today’s dollars). And en route to her fortune she would break the glass ceiling of two traditionally male professions: photography and real estate.

But first she would have to escape from 250 Sioux warriors and one lawsuit.

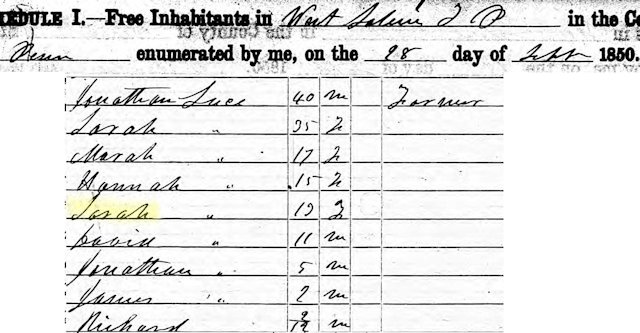

Sarah Luse was born in 1836 in Pennsylvania to Jonathan and Sarah Luse. She grew up on the Luse farm. At age twenty she married William James Larimer of Iowa. They soon moved to Kansas, where Sarah operated Mrs. Larimer’s Gem and Photograph Rooms.

Sarah Luse was born in 1836 in Pennsylvania to Jonathan and Sarah Luse. She grew up on the Luse farm. At age twenty she married William James Larimer of Iowa. They soon moved to Kansas, where Sarah operated Mrs. Larimer’s Gem and Photograph Rooms.

But Mr. Larimer suffered poor health, and in 1864 his physician advised him to move west where the mountain air might improve his health. The Larimers decided to move to far-flung Idaho and operate a photography business there.

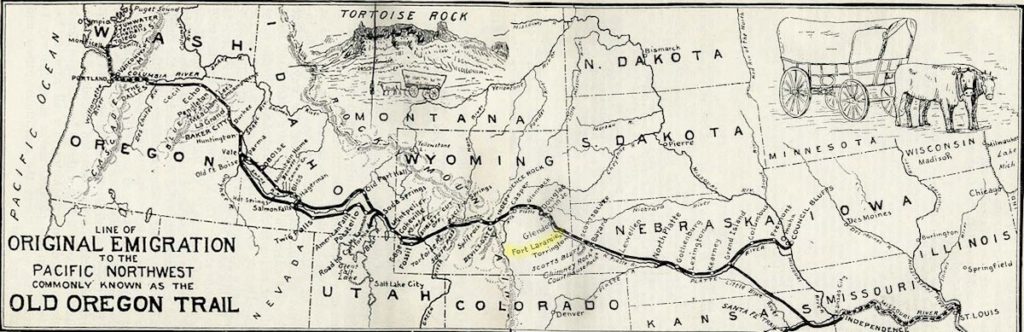

Packing their belongings, including photographic equipment, William and Sarah Larimer and son Frank, age seven, left Kansas on May 17, 1864 and soon joined a westbound wagon train headed by Josiah Kelly, also of Kansas. The train consisted of five wagons, a herd of livestock, and eleven immigrants. Among the eleven were Kelly’s wife Fanny and their adopted daughter Mary, age seven.

Migrating to the American West by wagon train was not for the meek. The travel was slow (ten to twenty miles a day). The route was rugged and desolate (not a Stuckey’s in sight). Along the way were the risks of dangerous animals, disease (especially cholera), and Native Americans who had a “not in my back yard” attitude about white settlement.

Westward migration took, in a word, grit.

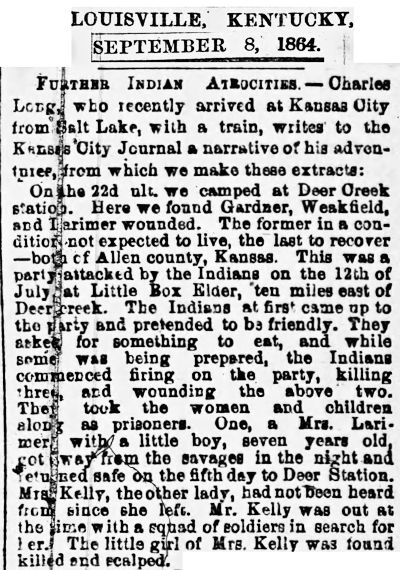

By July 12 the Kelly-Larimer wagon train was in Wyoming, traveling on the Oregon Trail. As the immigrants crossed Little Box Elder Creek eighty miles west of Fort Laramie they saw massed upon a bluff about 250 Sioux. Mrs. Larimer later recalled that the Sioux were “painted and equipped for the warpath.”

By July 12 the Kelly-Larimer wagon train was in Wyoming, traveling on the Oregon Trail. As the immigrants crossed Little Box Elder Creek eighty miles west of Fort Laramie they saw massed upon a bluff about 250 Sioux. Mrs. Larimer later recalled that the Sioux were “painted and equipped for the warpath.”

The immigrants circled their wagons, expecting an attack. Instead the Sioux approached peaceably. Their leader singled out Mr. Kelly, the wagon train leader.

Mrs. Kelly later recalled: “The savage leader immediately came toward him [Mr. Kelly], riding forward and uttering the words, ‘How! How!’ which are understood to mean a friendly salutation.”

The Sioux leader shook hands with all the white men and said he and his warriors would accompany the wagon train a while on its journey.

Fearing a trap, Josiah Kelly refused to budge. The Sioux chief then invited himself and his warriors to the immigrants’ supper.

The immigrant men nervously busied themselves: gathering firewood and food provisions, starting fires, tending to their livestock.

While the immigrant men were preoccupied, Mrs. Larimer later recalled, the Sioux suddenly “uttered a wild cry and fired a volley from their guns into the air.”

The Sioux attacked the immigrant party, quickly killing four of the men. Other immigrant men, including Mr. Kelly and Mr. Larimer, escaped into a forest. Left behind, Fanny Kelly and Sarah Larimer did not know the fate of their husbands.

As the women watched, the Sioux then claimed the immigrants’ horses and looted the wagon train for valuables. They ripped open flour sacks and feather mattresses. With their tomahawks they broke open trunks and crates. Seeing no value in the Larimers’ photographic equipment, they smashed it.

Fanny Kelly later recalled Sarah Larimer’s reaction: “Her agitation was extreme. Her grief seemed to have reached its climax when she saw the Indians destroying her property, which consisted principally of such articles as belong to the Daguerrean art. She had indulged in high hopes of fortune from the prosecution of this art among the mining towns of Idaho. As she saw her chemicals, picture cases, and other property pertaining to her calling being destroyed, she uttered such a wild despairing cry as brought the chief of the band to us, who, with gleaming knife, threatened to end all her further troubles in this world. . . . But my poor companion was in great danger, and perhaps it was a selfish thought of future loneliness in captivity which induced me to intercede that her life might be spared. I went to the side of the chief, and, assuming a cheerfulness I was very far from feeling, pled successfully for her life.”

The warriors then took captive Mrs. Larimer and son Frank and Mrs. Kelly and daughter Mary, put them on horses, and began the trip back to the Sioux village in the Powder River country.

As they rode after nightfall Mrs. Kelly waited for the right moment and lowered daughter Mary to the ground. Mary sought cover and watched her mother ride out of sight. A mile later Mrs. Kelly, too, slipped off her horse to escape but was quickly apprehended by her captors. She told them that she had merely dismounted to look for Mary after Mary had disappeared.

The warriors believed her but warned her against trying to escape. The warriors made a cursory search for Mary, continued on, and made camp that night.

Mrs. Larimer later recalled her first night in captivity: “While my child lay in a troubled sleep, I sat by his side, silently praying for God’s protecting mercy, and could see the hills above us dotted with Indians, stationed as pickets to give alarm in case of the appearance of approaching danger.”

The next day the chief’s messenger told Mrs. Larimer that the trip to the village would be too difficult for a child and that her son Frank would be allowed to ride a horse back to the wagon train. But Mrs. Larimer considered that option—a seven-year-old boy riding alone over the treacherous course they had just covered—equally difficult.

“I was convinced that the undertaking was too dangerous for a child to accomplish and concluded that nothing but coercion or death should cause our separation. . . . I . . . almost fancied I saw my dear child taken from my sight forever, and his limbs severed from the body, and the mutilated remains left upon the ground to satisfy the hungry appetite of wolves or birds of prey, when the bones would be allowed to bleach in the sun and storms, while his flaxen curls would be used to ornament a warrior’s belt and entitle him to the honor of adding one more plume to his crown, as a signal that he had, by the violence of his own hands, sent a soul to that bourne from whence no traveller returns. . . .

“I had from the first endeavored to gain the confidence of the Indians and cause them to believe we were resigned to our fate, that, their vigilance relaxing, a chance for escape might present itself.”

Mrs. Larimer told the messenger that she wished the boy to continue to the Sioux village. When the messenger seemed displeased, “I proceeded to enumerate the benefits that would be derived from Frank’s assistance in the Indian village, explaining how he could be taught to chop wood, attend children, and bear burdens at home, and when on the chase for game in the hills, draw the bow, and fire a gun, and dress the meat; and even on the warpath, sway the tomahawk. . . .

“The chief was evidently pleased with the gift of the child; or possibly it was with the belief that I was reconciled to our life of bondage, for arrangements for our comfort were made that had not been done before.”

As the party rode on toward the village, Mrs. Larimer recalled, “The pitiful face of [my] weary child aroused my courage to plead for a slower pace, with the feeble hope of being overtaken by pursuing friends; but the request was answered by the cheerless assurance that haste was necessary to safety; for if they were closely followed by our friends, our fate would be unquestioned, it being their duty to murder prisoners rather than relinquish them.”

At the next encampment, Mrs. Larimer recalled, came the only incident that did not fill her with fear: She watched as her captors evaluated the booty taken from the wagon train. Fierce warriors, otherwise clad only in breechcloths, tried on the immigrants’ clothing—silk hats and bonnets, shirts and vests and coats, ribbons and lace and artificial flowers, pantaloons, gloves.

The warriors had confiscated a comb. They ran it through their hair and then gave it to Mrs. Larimer to do the same. She unpinned her long hair and shook it loose. Then she noticed that the chief was staring at her.

“After a few moments of gloomy hesitation, he took a great knife from his belt, whetted it, examined the edge, and, turning to his men, addressed them in a brief speech in their own language.”

Holding the knife, he approached Mrs. Larimer. Fearing that he was going to scalp her, she begged an elder who spoke some English to intercede. He did. Sarah later learned that the chief had intended only to cut a lock of her hair.

Late on the second night of captivity her guards dozed. Mrs. Larimer later recalled: “To remain was a life of bondage and the companionship of barbarous Indians. I resolved to make an attempt to escape, and snatching [Frank], he awoke, and I lifted him from the bed; fearing that he might be only partially awakened and become frightened, I whispered, ‘I am about starting for home,’ and, clasping him closely in my arms, I looked around to discover any danger. All was quiet; not a sound, save the breathing of the sleepers, broke the silence. A few dim stars shone above the rocky peaks that surrounded us. Pressing him to my bosom in unspoken assurance of my fearless resolution to save him, I stepped noiselessly, but rapidly, across the camp to the place where we had entered it, and in precaution, instead of turning to the south by the way we had come, climbed a bluff to the westward, hoping in this way to evade pursuers.”

The Larimers were free. Now the only captive was Fanny Kelly.

When the warriors discovered the escape, they searched for the Larimers but soon gave up.

But the next day as mother and son trudged through the rugged terrain under the summer sun, Mrs. Larimer recalled, “A scarcely less terrible enemy, in the form of thirst, seized us, threatening our lives. Of hunger we had no consciousness, although it was a fast from seven meals, but water became the one absorbing thought—in it even our danger from the Indians was forgotten. . . .

“‘Mother,’ said little Frank, . . . ‘we might as well have been killed by the savages as to die of thirst.’ . . .

“It was now twenty-two hours since we had tasted water, and we seemed to sink under the influence of thirst. The way had been over a dry, sandy waste that was scorching under the sun. . . .

“It was more than one hundred hours since we had eaten food, yet we were not conscious of a desire for it.”

Mother and son eventually came across some damp ground from which they squeezed a few drops of water. Then, farther along, a pool—filled with small slithering snakes. “Frightening the reptiles away, and spreading a cloth upon the surface; we only drank of what strained through, lest we might swallow some tiny reptiles.”

Mother and son next came across an abandoned Sioux camp, where Mrs. Larimer found a pair of moccasins for Frank’s “bruised and bleeding feet.”

Then, on the second day, the Larimers began to see signs of white travelers: boot prints and shod horses’ hooves (“Savages do not wear boots, nor are their horses shod.”). Then they heard the lowing of a cow (“Indians only steal cattle for their meat.”).

They came across freshly chopped wood. Next they heard music.

Finally they came across a white man who was leading two horses.

He said to Mrs. Larimer: “Oh, yes, I already have heard of the Indians’ outbreak, and that you were carried away; but no one ever dreamed of your coming back by yourself. Two companies of soldiers have arrived at [Fort] Deer Creek, just beyond the river, on their way to chastise the red scoundrels. But, come along with me, and I will take you to the train.”

The man was traveling with a wagon train made up of mostly German immigrants.

Five days after the Larimers had been captured, they crossed the North Platte River and reached the safety of Fort Deer Creek.

Sarah Larimer’s grit had gotten her through.

At the fort was Mrs. Larimer’s husband, who had been hit in the thigh by an arrow during the attack.

“My husband was prostrated by loss of blood and the effects of his wound, and the news of our return had been so unexpected that he could scarcely realize our safety until he saw us by his side.”

Also at the fort was Fanny Kelly’s husband Josiah. Mrs. Larimer told him that Mary Kelly had escaped but that Fanny was still a captive.

Josiah Kelly and other immigrants rode out in search of Fanny and Mary Kelly. They found only Mary’s body. She had been shot with three arrows and scalped. Mary was buried where she died. The four immigrant men—three white, one black—killed in the attack were buried in a common grave. A buffalo robe was their shroud. (Photo from Find a Grave.)

Josiah Kelly and other immigrants rode out in search of Fanny and Mary Kelly. They found only Mary’s body. She had been shot with three arrows and scalped. Mary was buried where she died. The four immigrant men—three white, one black—killed in the attack were buried in a common grave. A buffalo robe was their shroud. (Photo from Find a Grave.)

As for Fanny Kelly, the Sioux held her captive for five more months before her freedom was secured by ransom, and she was delivered to the Army’s Fort Sully, South Dakota (by some accounts, under the aegis of Sitting Bull).

Five immigrants had been killed in what is now known in western history as the “Kelly-Larimer Massacre.”

Five immigrants had been killed in what is now known in western history as the “Kelly-Larimer Massacre.”

(Thanks to Donna Humphrey Donnell for the tip.)

A Woman of Grit (Part 2): Author, Photographer, Millionaire

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Women in Fort Worth History

I’m glad you have put this story together from the perspective of Sarah as a savvy entrepreneur - though the drama between these two ladies never seemed to cease. My family was part of the attacks on the Oregon and Overland trails on July 12. I’ve begun putting their story together, titled, Emigrant Tales of the Platte River Raids (pending, 2023).

@Hometown, where did the newspaper clipping come from? I’m having trouble finding the proper citation information in your posting. Please and thank you!

Louisville Daily Journal, Kentucky.

I am so surprised that we have never heard of her! I cant wait to read part two. I’m doing that now!

My sentiment exactly, Teresa. How could I immerse myself in Fort Worth history for ten years and not know of this woman?

Thank you Mike, just goes to show there are so many interesting characters with a Fort Worth connection, so many stories yet to be told and you’re the man who does it!…..Great job as usually!!!!!

Donna Humphrey Donnell

Thanks. Couldn’t do it without help from other history sleuths such as you. A real “Why have I not been told about this person before?” story.