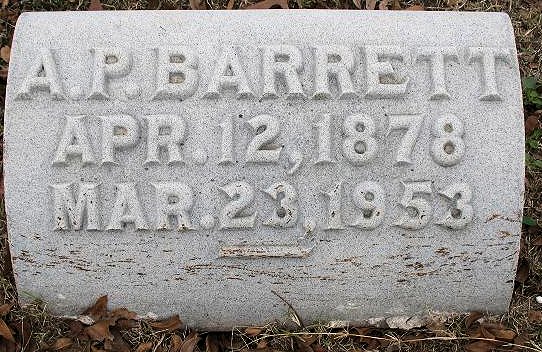

Alva Pearl Barrett was born in Tennessee in 1878. His father was a farmer and traveling preacher.

In 1892 the Barretts—including the first six of ten children—moved to Bonham in Fannin County.

In 1892 the Barretts—including the first six of ten children—moved to Bonham in Fannin County.

To help support the family’s cotton farm, young Alva and his brothers traveled by horseback selling clothes pins and other household goods.

In 1895, at age seventeen, Barrett began teaching in a one-room schoolhouse.

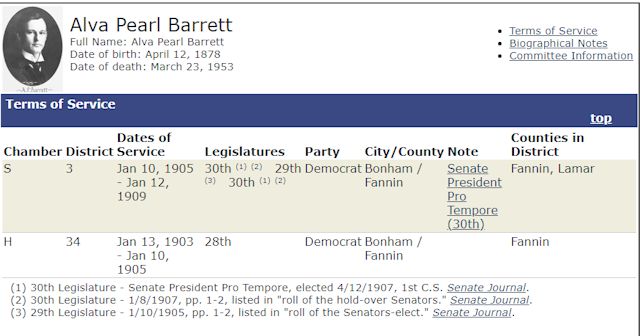

In 1902, while Barrett was still a teacher, Fannin County voters elected him to the state legislature. He took office in 1903 at age twenty-five. He served one term in the House and two terms in the Senate.

In 1902, while Barrett was still a teacher, Fannin County voters elected him to the state legislature. He took office in 1903 at age twenty-five. He served one term in the House and two terms in the Senate.

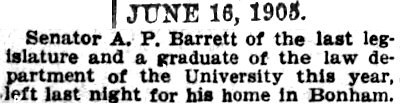

Most politicians become lawyers and then run for elected office. Not A. P. Barrett. He was already a Texas state senator when he graduated from University of Texas law school in 1905.

Most politicians become lawyers and then run for elected office. Not A. P. Barrett. He was already a Texas state senator when he graduated from University of Texas law school in 1905.

After he lost an election for Congress, Barrett opened a law office in San Antonio and became a wealthy man.

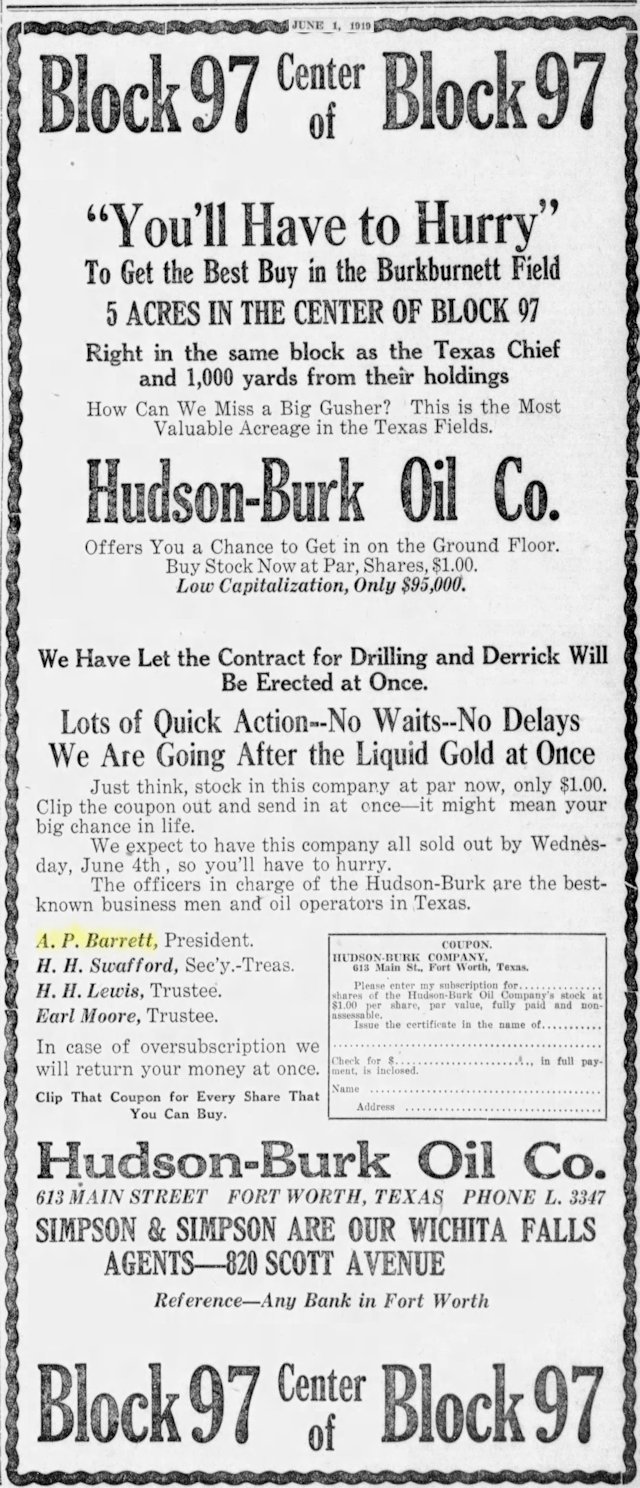

Then came 1917. William Knox Gordon struck oil near Ranger. Two years later Barrett, like so many men (including R. C. Bowen, see Part 1), went to the oil fields to make a fortune.

Ranger in 1919 was a wide-open boom town with all known forms of crime and vice. Barrett’s only vice was dipping snuff. The preacher’s son refused to live in such a fossil-fueled Sodom and instead moved to the comfortable Westbrook Hotel in Fort Worth—a favorite among oilmen—and commuted to the oil field.

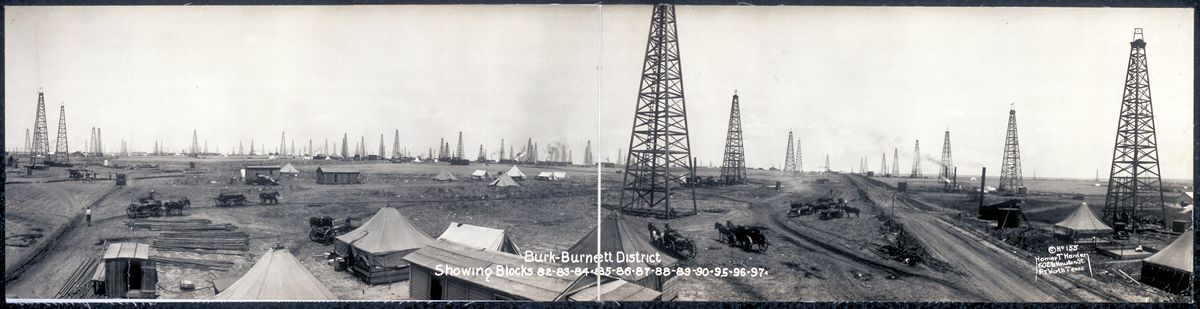

“We’re going after the liquid gold”: Barrett was president of Hudson-Burk Oil Company, which offered shares in its planned well in the Burkburnett field one hundred miles north of Ranger.

“We’re going after the liquid gold”: Barrett was president of Hudson-Burk Oil Company, which offered shares in its planned well in the Burkburnett field one hundred miles north of Ranger.

The Burkburnett field in 1919. (Photo from Library of Congress.)

The Burkburnett field in 1919. (Photo from Library of Congress.)

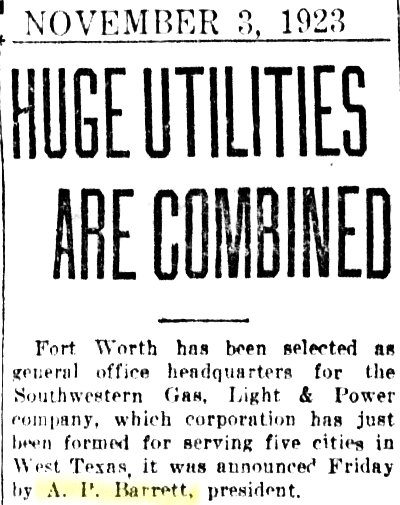

Alas, Barrett did not strike liquid gold and lost his fortune drilling for it. He then moved to New York City to learn the ways of high finance. Returned to Fort Worth, in 1923 he became the main stockholder and president of Ranger Gas Company, which became Southwestern Gas, Light & Power Company. The utility served five cities in the Ranger oil boom area.

Alas, Barrett did not strike liquid gold and lost his fortune drilling for it. He then moved to New York City to learn the ways of high finance. Returned to Fort Worth, in 1923 he became the main stockholder and president of Ranger Gas Company, which became Southwestern Gas, Light & Power Company. The utility served five cities in the Ranger oil boom area.

He sold his stock and, again like R. C. Bowen, put his money into mass transit:

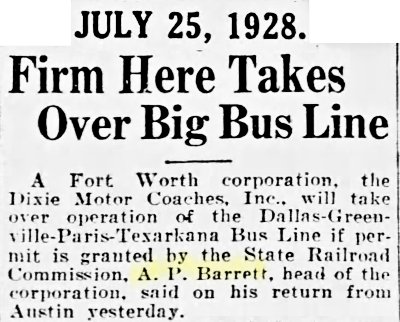

In 1928 Barrett took over a Dallas-based bus line and founded Dixie Motor Coaches.

In 1928 Barrett took over a Dallas-based bus line and founded Dixie Motor Coaches.

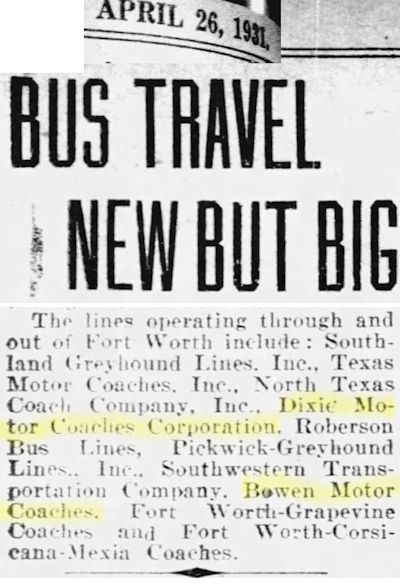

In 1931 A. P. Barrett’s Dixie bus line and R. C. Bowen’s bus line were two of ten lines serving Fort Worth.

In 1931 A. P. Barrett’s Dixie bus line and R. C. Bowen’s bus line were two of ten lines serving Fort Worth.

But later that year Barrett sold Dixie Motor Coaches. The company was absorbed—as was R. C. Bowen’s bus line—into the Continental Trailways national network in 1948.

But later that year Barrett sold Dixie Motor Coaches. The company was absorbed—as was R. C. Bowen’s bus line—into the Continental Trailways national network in 1948.

Meanwhile, Barrett, again like Bowen, branched out into a second form of mass transit.

Reportedly, one day in 1928 Barrett and his three-year-old son Hunter were in the yard of their home playing with a toy airplane. A motor droned, and Hunter saw overhead an airplane marked “TAT.”

Hunter said, “Daddy, I want that plane.”

Later that day Barrett and Hunter went to Meacham Field, where they watched airplanes arrive and depart. Barrett approached a crew member of a plane and asked about the plane marked “TAT.” Barrett said he might buy it.

“I’ll say it can’t be bought,” the crew member replied. “That plane belongs to Texas Air Transport.”

“Then,” Barrett said, “I’ll buy Texas Air Transport.”

And he did. And from whom did Barrett buy Texas Air Transport? From brothers R. C. and Temple Bowen, who had founded TAT in 1927.

After buying TAT (with some help from Amon Carter and other investors), A. P. Barrett founded the Texas Air Transport Broadcast Company, bought radio station KFQB, and changed the call letters to “KTAT.”

TAT planes carried passengers and mail in single-engine Lockheed airplanes. According to Jerry Flemmons in his book Amon: The Life of Amon Carter, Sr. of Texas, Barrett, who stood six-foot-four and was possessed of a deep voice, began each workday at TAT by leading his employees as they sang the song “My Old Fiddle”:

“My old fiddle, she’s tuned up good/Best old fiddle in the neighborhood.”

In 1929 Barrett founded Southern Air Transport. Barrett planned to merge TAT and Gulf Air Lines into Southern Air Transport, which would provide passenger and mail service from El Paso to Atlanta.

In 1929 Barrett founded Southern Air Transport. Barrett planned to merge TAT and Gulf Air Lines into Southern Air Transport, which would provide passenger and mail service from El Paso to Atlanta.

Also in 1929 Barrett’s wife Hazel christened a Fokker six-passenger airliner as TAT began daily service to El Paso. Her husband would soon sell Southern Air Transport to Aviation Corporation, which operated American Airways. Barrett would remain a stockholder and a vice president of American Airways.

Also in 1929 Barrett’s wife Hazel christened a Fokker six-passenger airliner as TAT began daily service to El Paso. Her husband would soon sell Southern Air Transport to Aviation Corporation, which operated American Airways. Barrett would remain a stockholder and a vice president of American Airways.

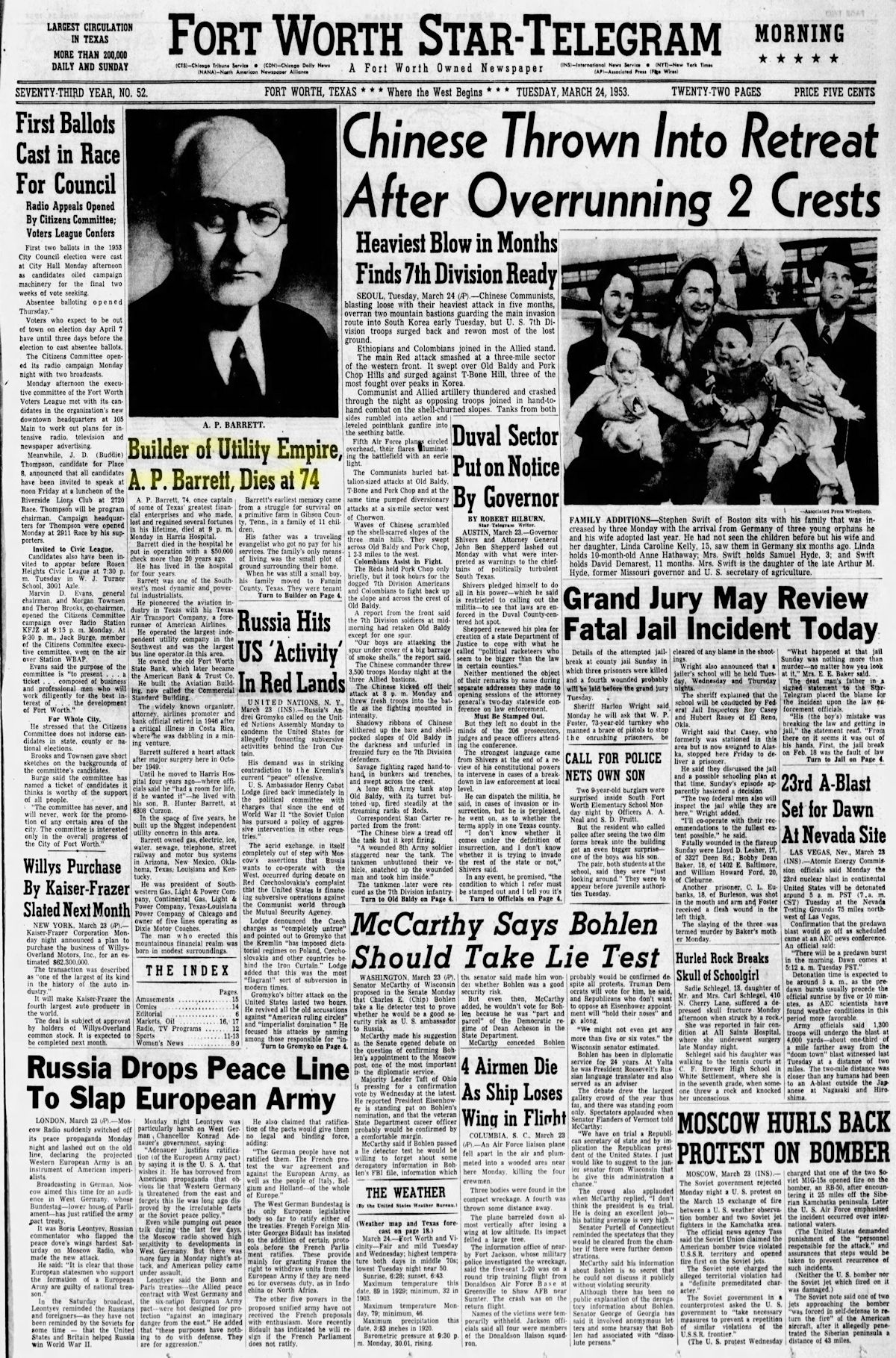

Like most capitalists, Barrett was diversified. He was president or board chairman of a finance company, an insurance company, three utility companies, a bank, a dairy, and an ice cream company.

He said: “It’s not success or wealth that counts—it’s the struggle—the adventure of making certain aims come true, of making this a bigger, better place, of achieving as much as possible in the short space of time allotted to us. I have been broke, hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt, gone with one meal a day, but a smile on my face, but Lord, how I do hate poverty. There’s plenty of wealth, plenty of brains, all that’s lacking is the spirit, the dogged determination to accomplish whatever you set out to accomplish, whatever the cost.”

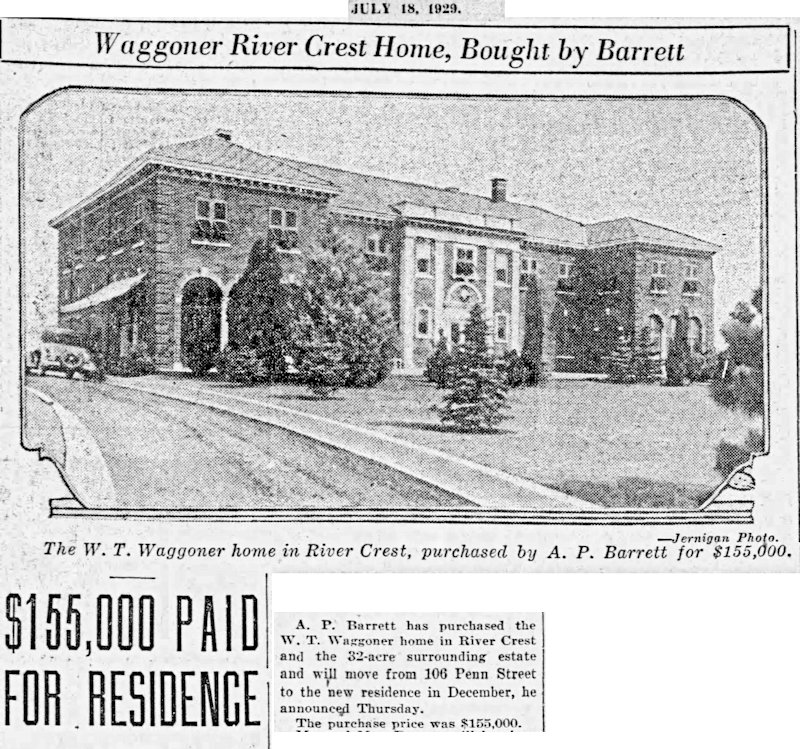

By 1929 Barrett had made back all the money he had lost in the oilfields and then some. That year he moved from Penn Street downtown to the nine thousand-square-foot mansion (Clarkson, 1925) of W. T. Waggoner in River Crest. He bought the property—for $155,000 ($2.3 million today)—because it was large enough (thirty-two acres) for an airstrip. Amon Carter and R. C. Bowen also lived in River Crest.

By 1929 Barrett had made back all the money he had lost in the oilfields and then some. That year he moved from Penn Street downtown to the nine thousand-square-foot mansion (Clarkson, 1925) of W. T. Waggoner in River Crest. He bought the property—for $155,000 ($2.3 million today)—because it was large enough (thirty-two acres) for an airstrip. Amon Carter and R. C. Bowen also lived in River Crest.

Meanwhile, the Star-Telegram wrote, Waggoner moved back to his mansion on Summit Avenue on Quality Hill.

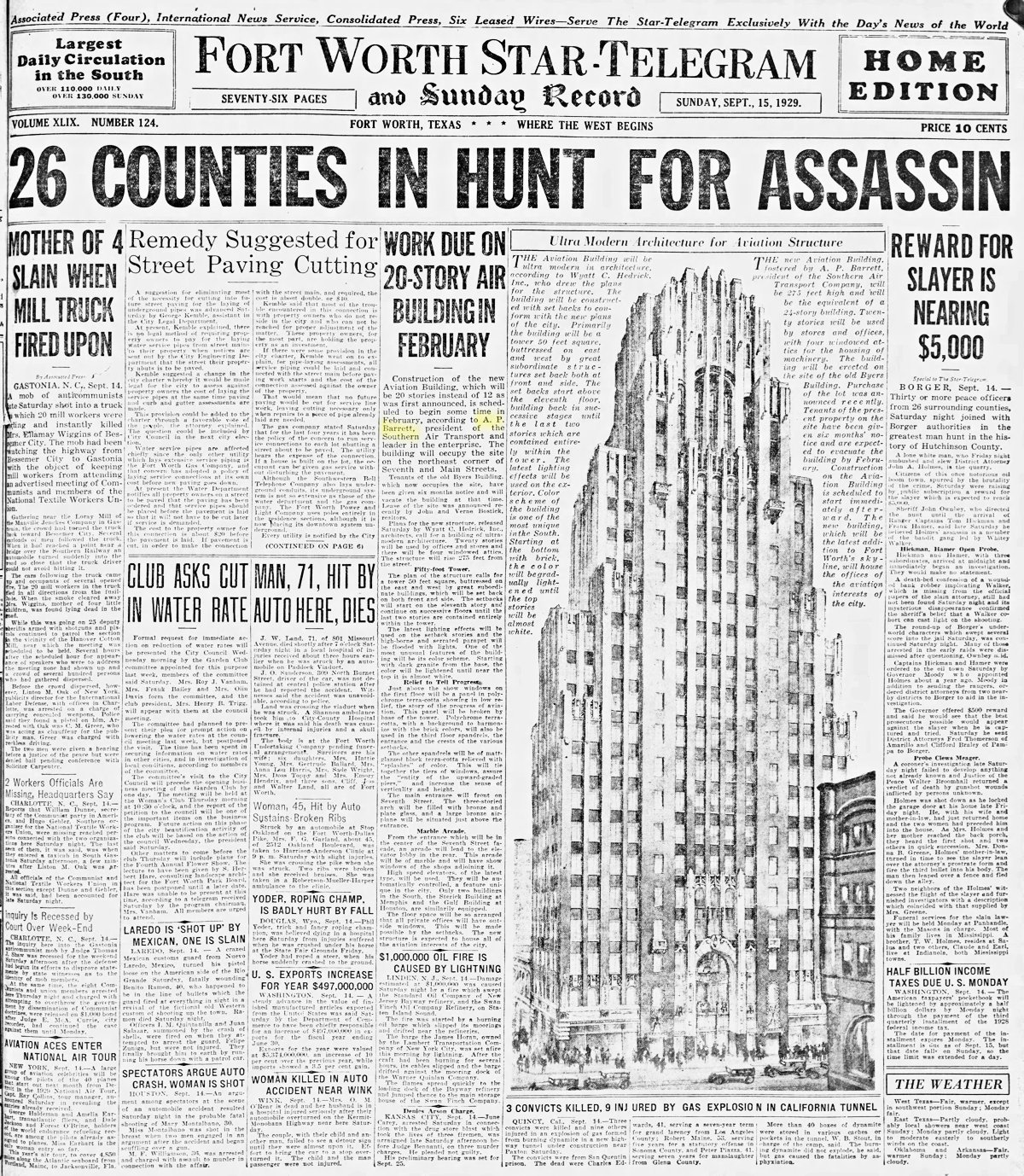

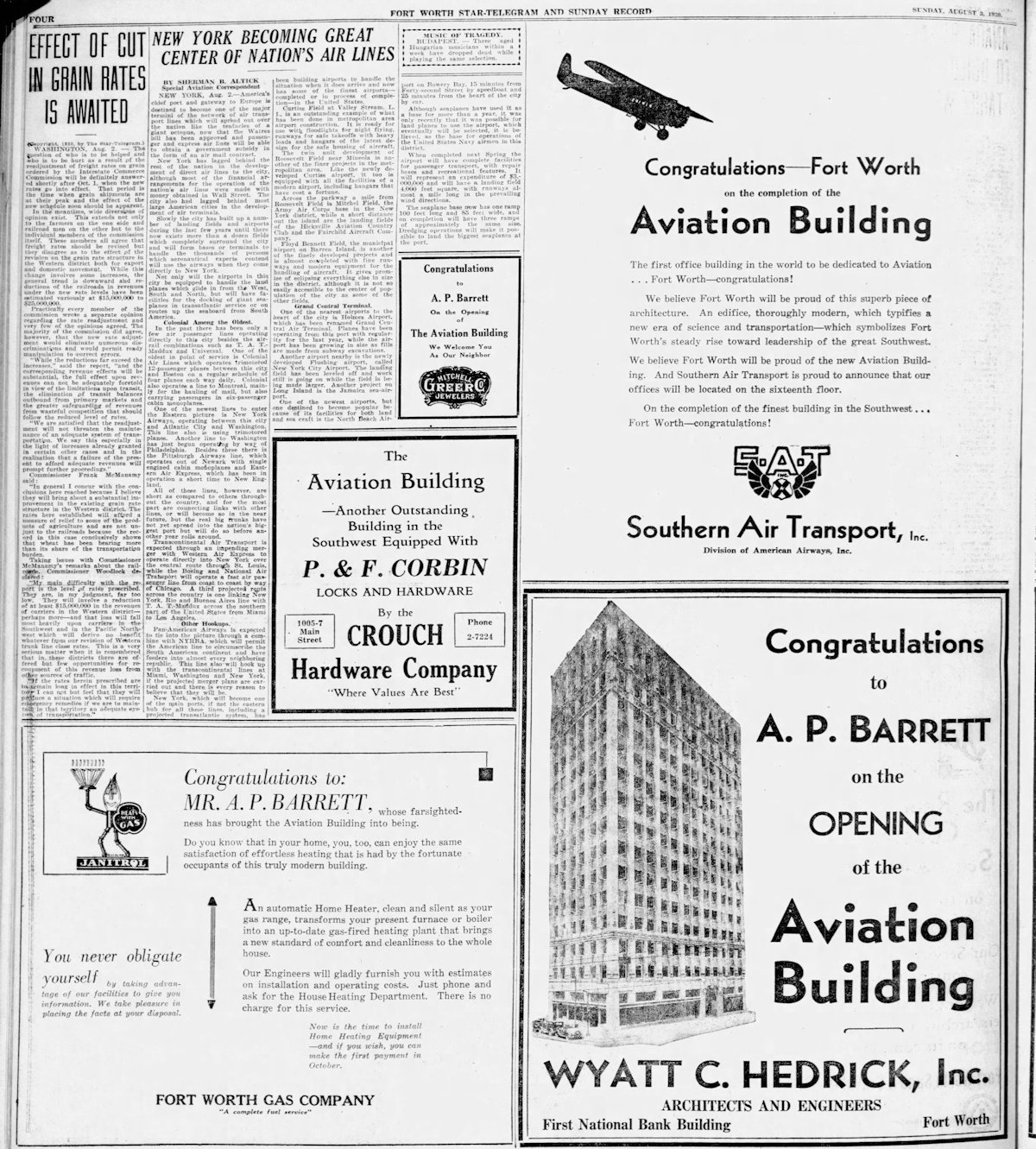

An airline is a business, and a business needs a home. So, Barrett built the Aviation Building at the corner of Main and 7th streets adjacent to the Palace Theater. The seventeen-story building, designed by the firm of architect Wyatt Hedrick, was art deco with Aztec and Mayan motifs.

An airline is a business, and a business needs a home. So, Barrett built the Aviation Building at the corner of Main and 7th streets adjacent to the Palace Theater. The seventeen-story building, designed by the firm of architect Wyatt Hedrick, was art deco with Aztec and Mayan motifs.

Barrett’s office was on the sixteenth floor. The penthouse housed Barrett’s radio station KTAT. Barrett was president of Southwest Broadcasting Company.

Among those congratulating Barrett on his new building were Southern Air Transport and the architect himself. In 1930 SAT was still a division of Aviation Corporation’s American Airways, which in 1934 became American Airlines.

Among those congratulating Barrett on his new building were Southern Air Transport and the architect himself. In 1930 SAT was still a division of Aviation Corporation’s American Airways, which in 1934 became American Airlines.

This 1945 photo shows the Aviation Building dwarfing the Palace Theater. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries W. D. Smith Commercial Photography Collection.)

(The Aviation Building went up fast and came down fast. Construction was completed in less than six months. When the building was imploded in 1978 it fell in less than ten seconds.)

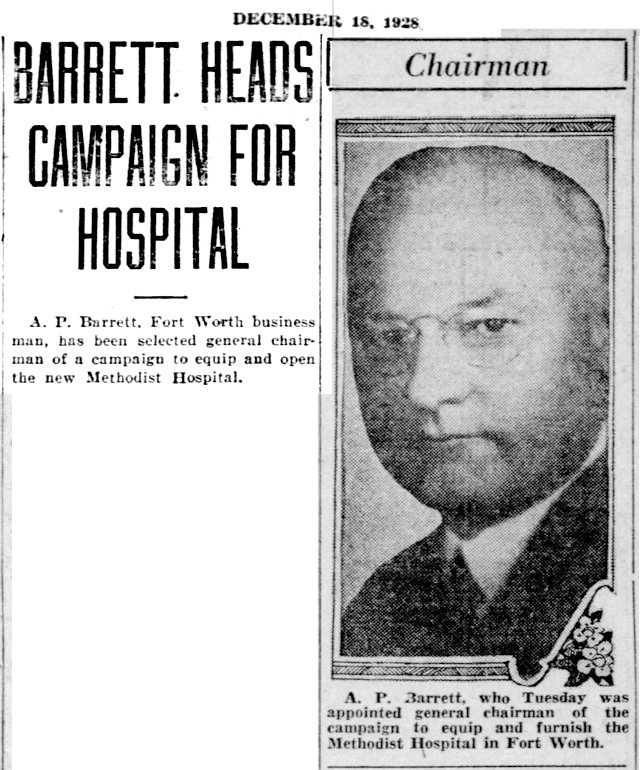

Barrett also was a philanthropist. In 1928 he headed a fund drive to furnish and equip Methodist (Harris) Hospital and donated $50,000 ($800,000 today) of his own money. In 1930 he also led a fund drive for Our Lady of Victory Academy.

Barrett also was a philanthropist. In 1928 he headed a fund drive to furnish and equip Methodist (Harris) Hospital and donated $50,000 ($800,000 today) of his own money. In 1930 he also led a fund drive for Our Lady of Victory Academy.

In 1949 Barrett’s health began to decline. He spent the last two years of his life living in a suite in the hospital he had helped to equip.

He died in 1953.

He died in 1953.

Alva Pearl Barrett is buried in San Antonio, where he had practiced law for ten years.

Alva Pearl Barrett is buried in San Antonio, where he had practiced law for ten years.