Although a bust of James Edward Papworth probably would not be displayed in a rogues gallery of Cowtown criminals—alongside the busts of, say, Tincy Eggleston, Cecil Green, Jim Thomas, James Brown Miller ad homicidium—Papworth deserves at least a participation trophy if only for the audacity of the crimes he plotted.

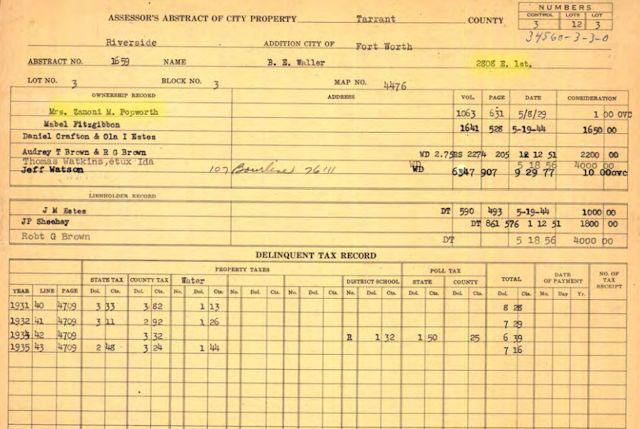

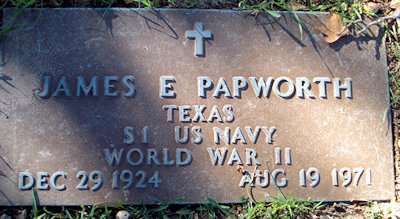

Papworth was born in 1924 to John William Papworth and Zanoni Papworth. Father Papworth was a nurseryman, as was his father. John and family lived at 2808 East 1st Street.

Papworth was born in 1924 to John William Papworth and Zanoni Papworth. Father Papworth was a nurseryman, as was his father. John and family lived at 2808 East 1st Street.

John and Zanoni divorced in 1929. Two years later father John was sentenced to a year in prison for not providing child support for son James.

In 1941 James Papworth was a junior at Carter-Riverside High School. He was a member of the school band and ROTC.

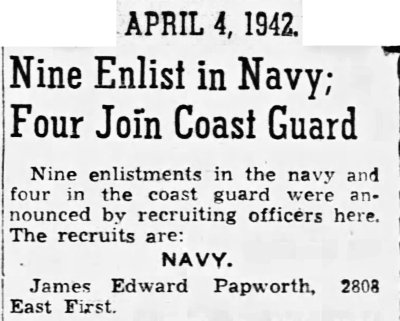

In April 1942 he enlisted in the Navy. He would serve on the tank landing ship LST-973, the fleet replenishment oiler U.S.S. Chemung, and the destroyer U.S.S. Woolsey.

In April 1942 he enlisted in the Navy. He would serve on the tank landing ship LST-973, the fleet replenishment oiler U.S.S. Chemung, and the destroyer U.S.S. Woolsey.

So far, so good.

But in 1942 while on shore leave in New York City Papworth was arrested for stealing a car. Actually he stole more than a car: He stole a car with the owner’s wife in it. Papworth was arrested in the company of the wife, whose husband had reported his car stolen and his wife AWOL. Posterity does not record how the husband reacted, but a grand jury reacted by declining to indict Papworth.

In 1945 at age twenty-one Seaman First Class James Edward Papworth was discharged from the Navy. He moved in with his mother, who had relocated to 3534 Avenue H in Poly.

Civilian Papworth found work as a mechanic and also worked at Leonard’s. Zanoni, a single mother, worked as a matron at the courthouse, a saleswoman, and a gift-wrapper at Cox’s department store.

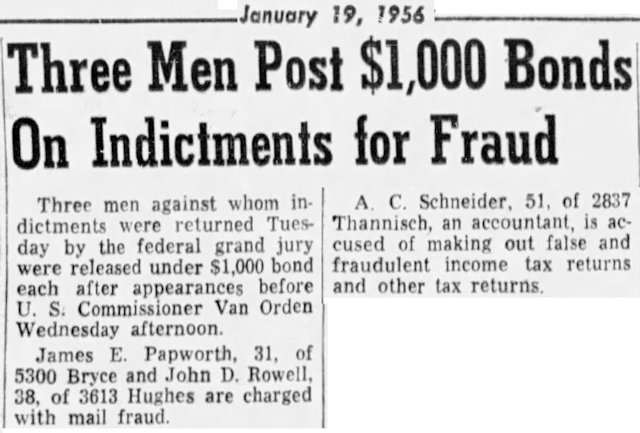

Fast-forward to 1956. James Edward Papworth had stayed out of court and out of jail for fourteen years. Then he was charged with seven counts of mail fraud in connection with his company, Federal Business Investments, which promised to sell businesses for their owners for a fee.

Fast-forward to 1956. James Edward Papworth had stayed out of court and out of jail for fourteen years. Then he was charged with seven counts of mail fraud in connection with his company, Federal Business Investments, which promised to sell businesses for their owners for a fee.

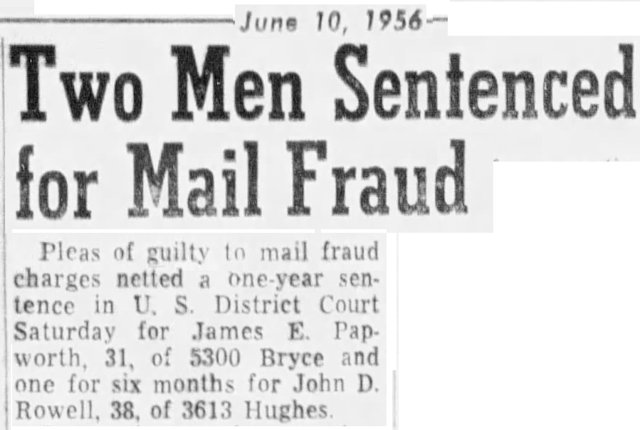

The Star-Telegram reported that Papworth was found guilty and sentenced to one year in prison.

The Star-Telegram reported that Papworth was found guilty and sentenced to one year in prison.

Then came 1957. James Edward Papworth was in Seagoville federal penitentiary. Prison is the perfect setting for social networking. In Seagoville Papworth met John Wesley Taylor. Taylor had been manager of Fort Worth National Bank’s branch at Carswell Air Force Base until he went to prison for embezzling $7,300 from the bank to cover gambling losses.

Taylor’s crime gave Papworth the idea for the first of his two long shots—an audacious crime indeed.

Papworth mined Taylor’s detailed knowledge of the air base and the branch bank: ways in, ways out, guards, alarms, the safe, the best times to make an unauthorized withdrawal.

Taylor provided Papworth with a floorplan of the branch bank, said the bank was at its ripest on payroll day on the last day of each month. How ripe? Five hundred thousand dollars ($4.5 million today).

After the two men were released from prison, Papworth’s plotting moved from abstracts to tangibles.

The execution of such a robbery, Papworth knew, called for someone more daring than he.

Enter Gene Paul Norris.

Gene Paul Norris knew his way around an audacious robbery plan. In 1952 he and three other men had robbed two Cubans of $248,000 ($2.4 million today) at the Western Hills Hotel.

Papworth knew Norris only by reputation. So he asked another ex-con, James Walter McFarland Jr., to introduce him to Norris. McFarland had met Norris in prison in 1945. More in-stir social networking.

McFarland introduced Papworth to Norris at the Beachcomber bar on Jacksboro Highway. Papworth told Norris about his plan. Norris was all in. Later one police theory was that Norris needed money to try to get his big brother Pete out of prison.

Gene Paul Norris, like Tincy Eggleston, Cecil Green, Jim Thomas, and James Brown Miller, belonged in Cowtown’s pantheon of crime. Front and center. In fact, Fort Worth Police Chief Cato Hightower suspected that Norris had killed Eggleston and Green—and seven other men. Some law enforcement officials put Norris’s body count north of forty.

Hightower called Norris a “madman” who killed for money and “didn’t mind seeing a person die.”

After Papworth brought Norris into the robbery plot, Norris recruited a fifth ex-con, William Carl Humphrey, who sometimes served as Norris’s bodyguard.

McFarland was to receive 10 percent of the robbery money for introducing Papworth to Norris. The remaining 90 percent of the money would be split by Papworth, Norris, Humphrey, and Taylor.

Papworth gave Norris the floorplan of the bank, and the planning began in detail. Papworth drove past the gates of the Air Force base a few times and made drawings.

He also drove past a house on Meandering Road near the base.

Why?

Because that was the home of Mrs. Elizabeth Barles and her twelve-year-old son, Jean Jolley.

Gene Paul Norris would need an “open sesame”—a way to gain access to a high-security bank in a high-security Air Force base.

John Wesley Taylor, the convicted former manager of the base bank, had told Papworth and Norris about Mrs. Barles. She worked at the bank.

On the day of the robbery Norris would go to Mrs. Barles’s home and force her to give him her key to the bank and the key to her car, which had a base access sticker on its windshield. Norris would then kill Mrs. Barles.

Norris would get past security guards at the east gate of Carswell by wearing Mrs. Barles’s clothing and impersonating her as he drove her car.

(Did I mention that this plot was audacious?)

Norris planned to kill the branch bank’s manager and shoot his way out if necessary. He would kill anyone who saw his face.

When Taylor realized that Norris planned to kill Mrs. Barles, a friend, he contacted the FBI about the plot. The FBI was definitely interested: By 1957 Gene Paul Norris, just as his brother Pete had been in 1942, was on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List.

Taylor agreed to serve as informant.

Lawmen, tipped a month ahead of the planned robbery, began to follow the three men using the “picket” form of surveillance.

“Just like in a picket line,” Chief Hightower later explained. “One unmarked car is assigned to follow them just so far, regardless of what happens. Then the next car picks them up at a designated spot. That way they’re not aware they’re being tailed.”

Police told Mrs. Barles of the danger she was in. They moved her and her son out of their house on the day before the planned robbery. Then police staked out her house. Police also planned to station marksmen at the base bank on the day of the robbery.

But on April 29, one day before the planned robbery, Papworth, Norris, and Humphrey set out to make a dry run of the robbery route from the Barles home to the Air Force base.

Papworth drove in his car with Norris as passenger. Humphrey followed in his 1957 Chevrolet. His car contained a twelve-gauge shotgun with a supply of shells, a nine-millimeter automatic pistol, and a .38-caliber pistol.

Police in their picket line followed both cars.

Norris wanted Papworth to show him where Mrs. Barles lived. But Papworth got cold feet, intentionally took a wrong turn, and told Norris he was lost and could not find the Barles house.

Norris became angry, got out of Papworth’s car and into Humphrey’s car. As Norris slammed the door, he said to Papworth: “You’ve had your last chance with me.”

Papworth, no doubt feeling the crosshairs of a killer on his back, drove to his home in Sansom Park, unaware that two FBI agents followed him.

That wrong turn may have been the right turn for James Edward Papworth. Had he not angered Norris, Papworth might have been the third victim of what happened next.

As Humphrey and Norris drove on without Papworth, police followed the Humphrey car.

On Meandering Road Norris and Humphrey realized they were being followed. They turned around and headed for Jacksboro Highway.

Soon they were being followed by three cars carrying eleven lawmen.

Chief Hightower later said: “We decided these men were too dangerous to let this thing [the bank robbery] happen. Knowing how many he [Norris] had killed—and knowing he planned to shoot his way back out of the payroll office—we had every reason to believe he’d kill the woman [Mrs. Barles] and her little [boy]. Therefore, we couldn’t let it come off. We had to take him when we saw him.”

On Jacksboro Highway Norris began shooting at his pursuers and shredding the floorplan of the bank and throwing the evidence out the window.

The convoy at times reached 120 miles per hour.

Hightower later said: “Every time the [Norris] car would turn right, Gene Paul would fire at us from his window in the front seat. We’d see the flash, and we were returning the fire. He didn’t hit us.”

Near Springtown Humphrey turned onto a winding, muddy road. He lost control of his car, which clipped two trees and smashed through a fence before stopping near Walnut Creek.

Norris and Humphrey came out of their wrecked car with guns blazing, Norris with a shotgun, Humphrey with a pistol. The eleven officers also came out with guns blazing.

“It sounded like the Fourth of July,” Hightower later said. “I heard bullets whistling at me, but I was only thinking of getting them.

“Gene Paul was hit as he tried to get up a creek bank. That’s when our shots started showing effects” Norris, peppered with bullets, slowly slid backward down the slope and into the creek. Humphrey, shot in the left leg and chest, fell onto a small island fifty yards from Norris.

Walnut Creek was their River Styx: Humphrey was shot twenty-three times, Norris twenty-eight.

Humphrey died with $43 in his pockets. Norris had $63—and a tattered address book that he was shredding even as he shot at the lawmen who were cutting him down. The address book contained the address of James Edward Papworth.

A few hours later eight police cars arrived at Papworth’s house to arrest him.

Papworth claimed not to know why he had been arrested, claimed not to know Norris and Humphrey.

Mrs. Barles and her son Jean were driving in her car, listening to the radio, when they heard the news that Norris had been killed. Jean later said that when he saw his mother “let on a big smile” he understood that she had been Norris’s intended victim.

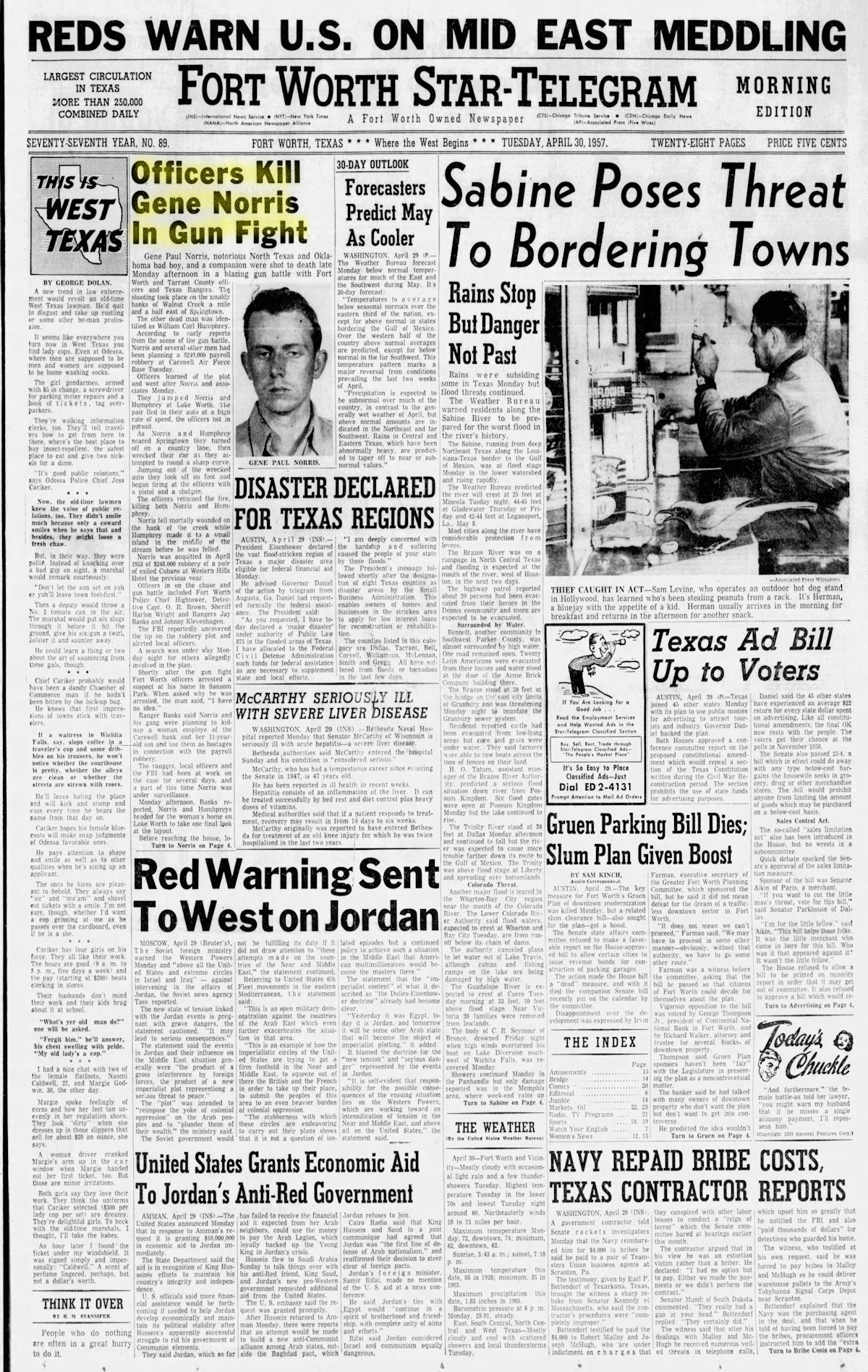

The killing of Gene Paul Norris, “notorious North Texas and Oklahoma bad boy,” was front-page news.

The killing of Gene Paul Norris, “notorious North Texas and Oklahoma bad boy,” was front-page news.

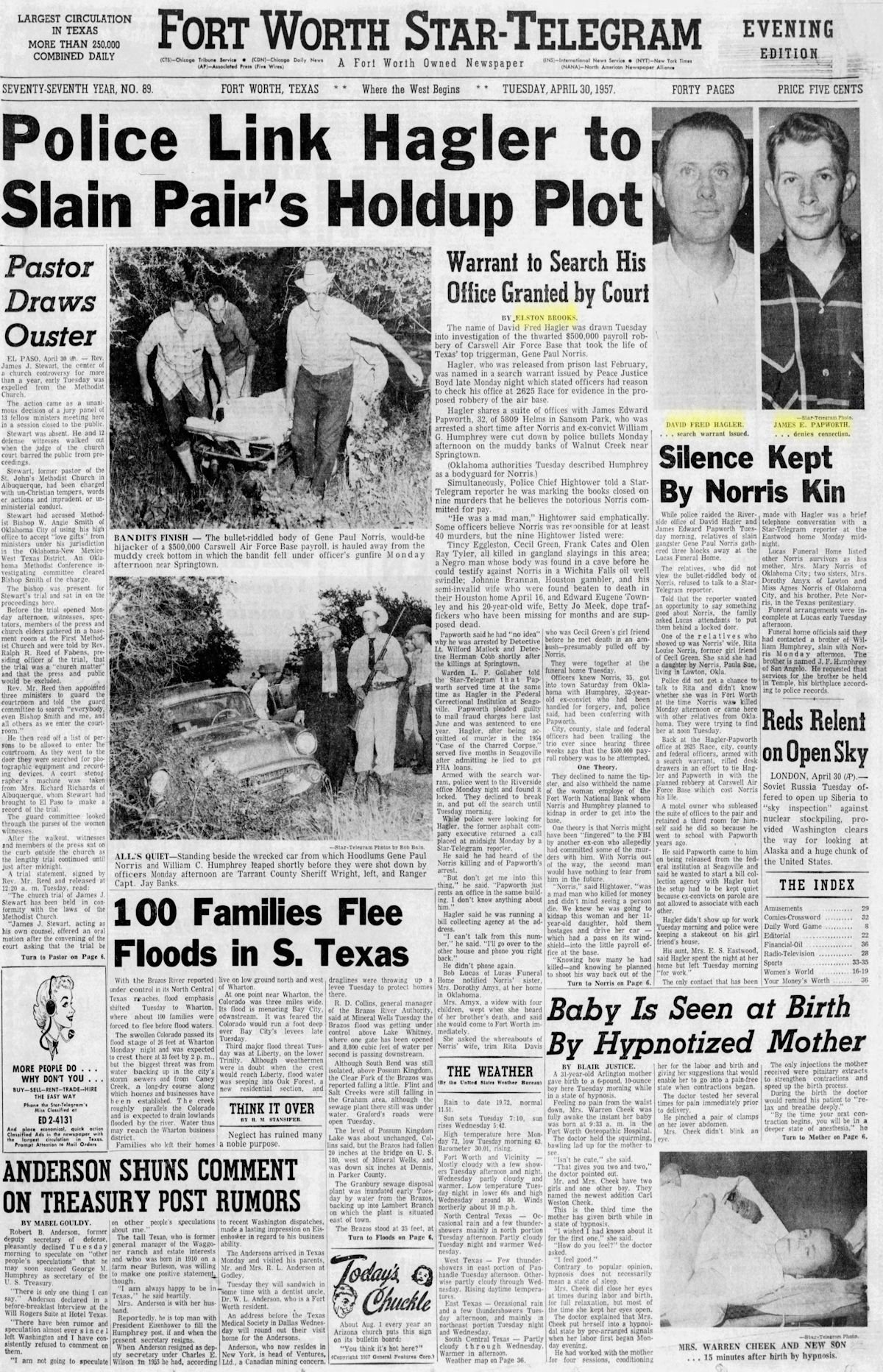

Police also questioned David Fred Hagler, who had an audacious criminal career of his own. Papworth had met Hagler, like Taylor, via Seagoville social networking. After Papworth and Hagler were released from prison, they opened a bill collection agency on Race Street in Riverside. After Norris and Humphrey were killed, police searched the Papworth-Hagler office and found Norris’s telephone number and a drawing of Carswell Air Force Base’s gates.

Police also questioned David Fred Hagler, who had an audacious criminal career of his own. Papworth had met Hagler, like Taylor, via Seagoville social networking. After Papworth and Hagler were released from prison, they opened a bill collection agency on Race Street in Riverside. After Norris and Humphrey were killed, police searched the Papworth-Hagler office and found Norris’s telephone number and a drawing of Carswell Air Force Base’s gates.

But police concluded Hagler was not involved in the robbery plot.

(Note the Elston Brooks byline. Before he became an entertainment columnist, Brooks was a police reporter.)

Papworth, told by police that Gene Paul Norris was dead, did not dare to believe them. So, police took him to Lucas Funeral Home to view the bullet-riddled bodies of Norris and Humphrey.

“Up till then, I’d only heard they were dead,” Papworth said. “It sure was a relief to see that they were dead.”

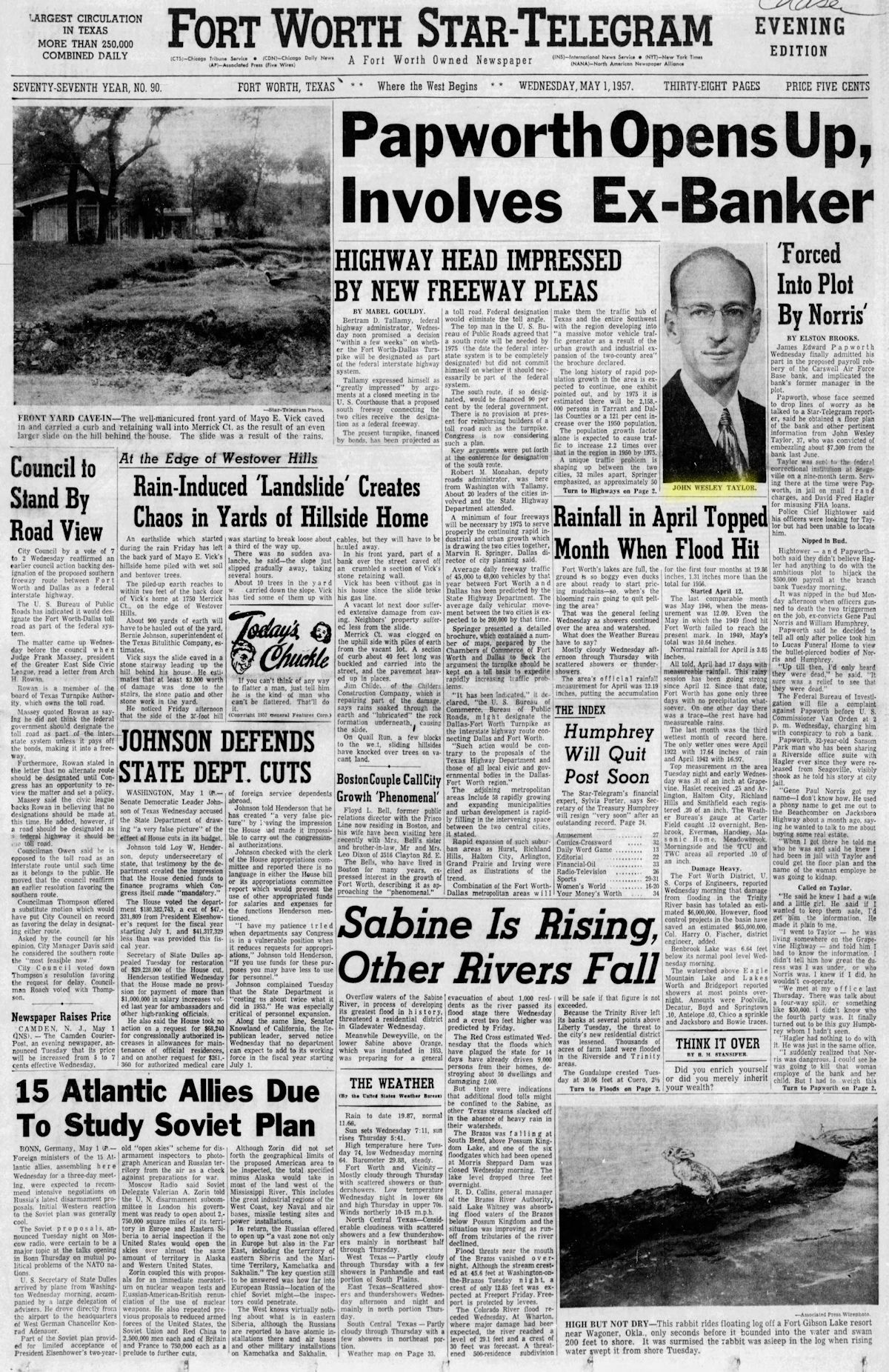

That’s when Papworth decided it was safe to tell all. He implicated John Wesley Taylor and James Walter McFarland Jr. He made several confessions to plotting the robbery, including one filmed by WBAP-TV.

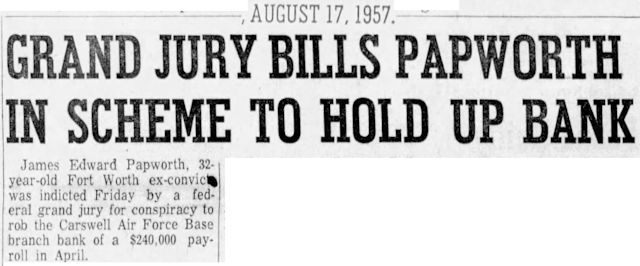

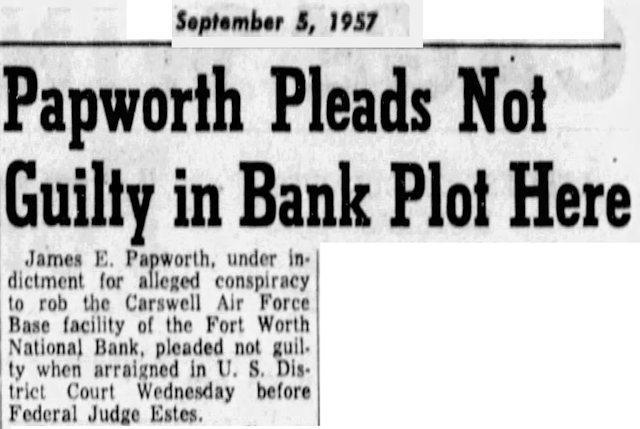

In August 1957 Papworth was indicted for conspiring to rob the Carswell bank.

In August 1957 Papworth was indicted for conspiring to rob the Carswell bank.

Papworth pleaded not guilty despite his earlier confessions.

Papworth pleaded not guilty despite his earlier confessions.

At trial Papworth’s attorneys portrayed him as a victim, said Gene Paul Norris had threatened to kill Papworth and his wife and daughter if Papworth refused to take part in the robbery. Attorneys presented three lawmen, including Dallas County Sheriff Bill Decker, who testified that Norris was a “vicious killer” who would carry out such a threat.

The prosecution claimed that Papworth was the mastermind behind the planned robbery and had been willing “to turn a mad dog [Norris] loose” to kill anyone who stood in his way.

In the course of investigating the bank robbery plot, investigators uncovered Papworth’s second long shot of 1957. The Star-Telegram reported that investigators found in Papworth’s wallet “an elaborate pencil sketch of [Kay] Kimbell’s office in the headquarters of the Kimbell Milling Company at 2200 S. Main.”

In the course of investigating the bank robbery plot, investigators uncovered Papworth’s second long shot of 1957. The Star-Telegram reported that investigators found in Papworth’s wallet “an elaborate pencil sketch of [Kay] Kimbell’s office in the headquarters of the Kimbell Milling Company at 2200 S. Main.”

Papworth was plotting to steal Kimbell’s art collection.

During a court hearing, “The startling disclosure on the projected art robbery was made by Police Chief Hightower.

“‘Kay Kimbell is the owner of some very valuable paintings,’ Hightower testified. ‘They are in his office. Papworth planned to get them. We had information he had asked another party how he could dispose of them, and that party told him he didn’t know how it could be done.’”

Investigators said Norris and Humphrey also had been part of Papworth’s art-theft plot.

The Star-Telegram hinted that Papworth may have planned to acquire Kimbell’s art works by extortion:

“An unclarified reference to ‘extortion’ was made by U.S. Attorney [Heard] Floore while questioning Hightower on the Kimbell robbery scheme. ‘Is obtaining such paintings by extortion a violation of state law?’ Floore asked.

“‘Yes,’ responded Hightower.”

Kay Kimbell’s art collection was world class and included late Renaissance, eighteenth-century English, nineteenth-century French, and nineteenth-century American painters. An art expert estimated that the paintings in Kimbell’s office accounted for $2 million ($18 million today) of the collection’s $5 million total value.

On September 14 Papworth was charged with conspiracy in the planned art theft. (Note that John A. Hulen had died.)

On September 14 Papworth was charged with conspiracy in the planned art theft. (Note that John A. Hulen had died.)

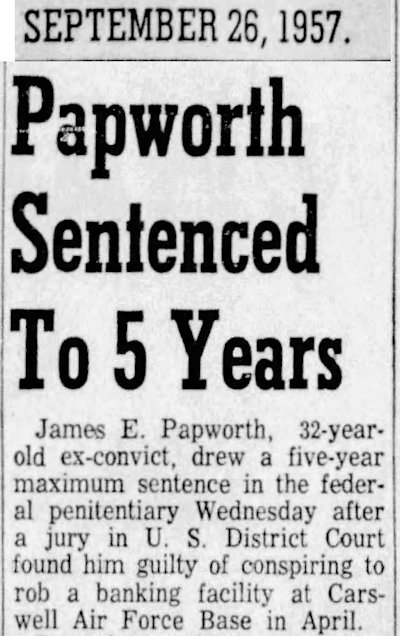

Eleven days after Papworth was charged with conspiring to rob Kay Kimbell, he was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison for conspiring to rob the Carswell bank. The Star-Telegram wrote that “Papworth’s pale, thin face turned a shade whiter” when the jury foreman read the verdict.

Eleven days after Papworth was charged with conspiring to rob Kay Kimbell, he was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison for conspiring to rob the Carswell bank. The Star-Telegram wrote that “Papworth’s pale, thin face turned a shade whiter” when the jury foreman read the verdict.

Papworth told the judge, “I hardly know how I became entangled in such a web of circumstances.”

Apparently prosecutors did not pursue the charge against Papworth for plotting to rob—or extort—Kay Kimbell, perhaps because Papworth’s co-conspirators—Norris and Humphrey—could not be “flipped” to provide testimony against him from the grave.

Fast-forward to 1961. In July Papworth was released from prison.

Fast-forward to 1961. In July Papworth was released from prison.

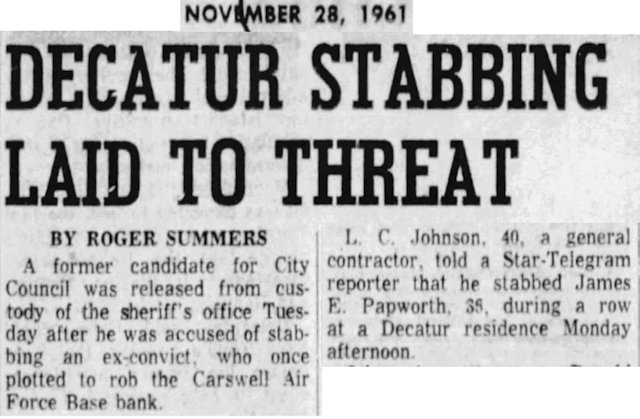

Four months later Papworth was stabbed by L. C. Johnson, a former candidate for Fort Worth city council. Papworth had worked for Johnson. Johnson said he stabbed Papworth after Papworth threatened him as the two men argued over money at a house in Decatur.

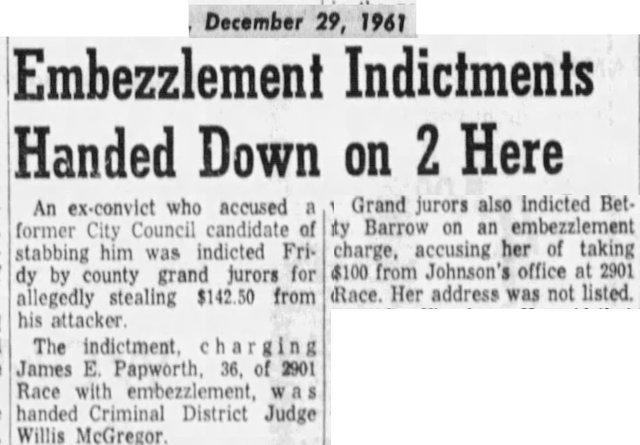

A month later Papworth was indicted for embezzling $142 from Johnson. Also indicted for embezzling money from Johnson was Betty Barrow. Barrow, like Papworth, had worked for Johnson.

A month later Papworth was indicted for embezzling $142 from Johnson. Also indicted for embezzling money from Johnson was Betty Barrow. Barrow, like Papworth, had worked for Johnson.

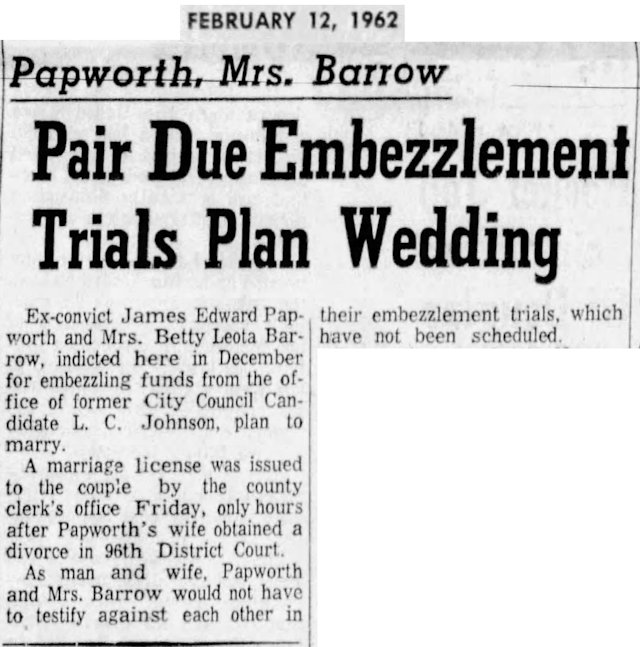

In February 1962, just hours after Papworth’s wife was granted a divorce, Papworth and Betty Barrow were issued a marriage license. Papworth and Barrow, as husband and wife, could not be compelled to testify against each other in their upcoming trials for embezzlement.

In February 1962, just hours after Papworth’s wife was granted a divorce, Papworth and Betty Barrow were issued a marriage license. Papworth and Barrow, as husband and wife, could not be compelled to testify against each other in their upcoming trials for embezzlement.

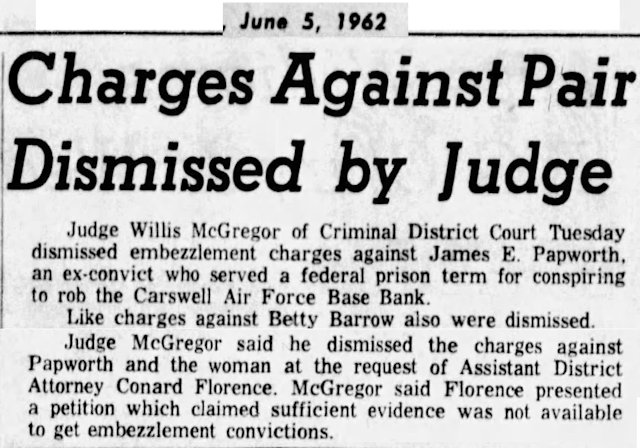

Sure enough, embezzlement charges against the pair were dropped because of insufficient evidence.

Sure enough, embezzlement charges against the pair were dropped because of insufficient evidence.

Charges against L. C. Johnson, who had stabbed Papworth, also were dropped.

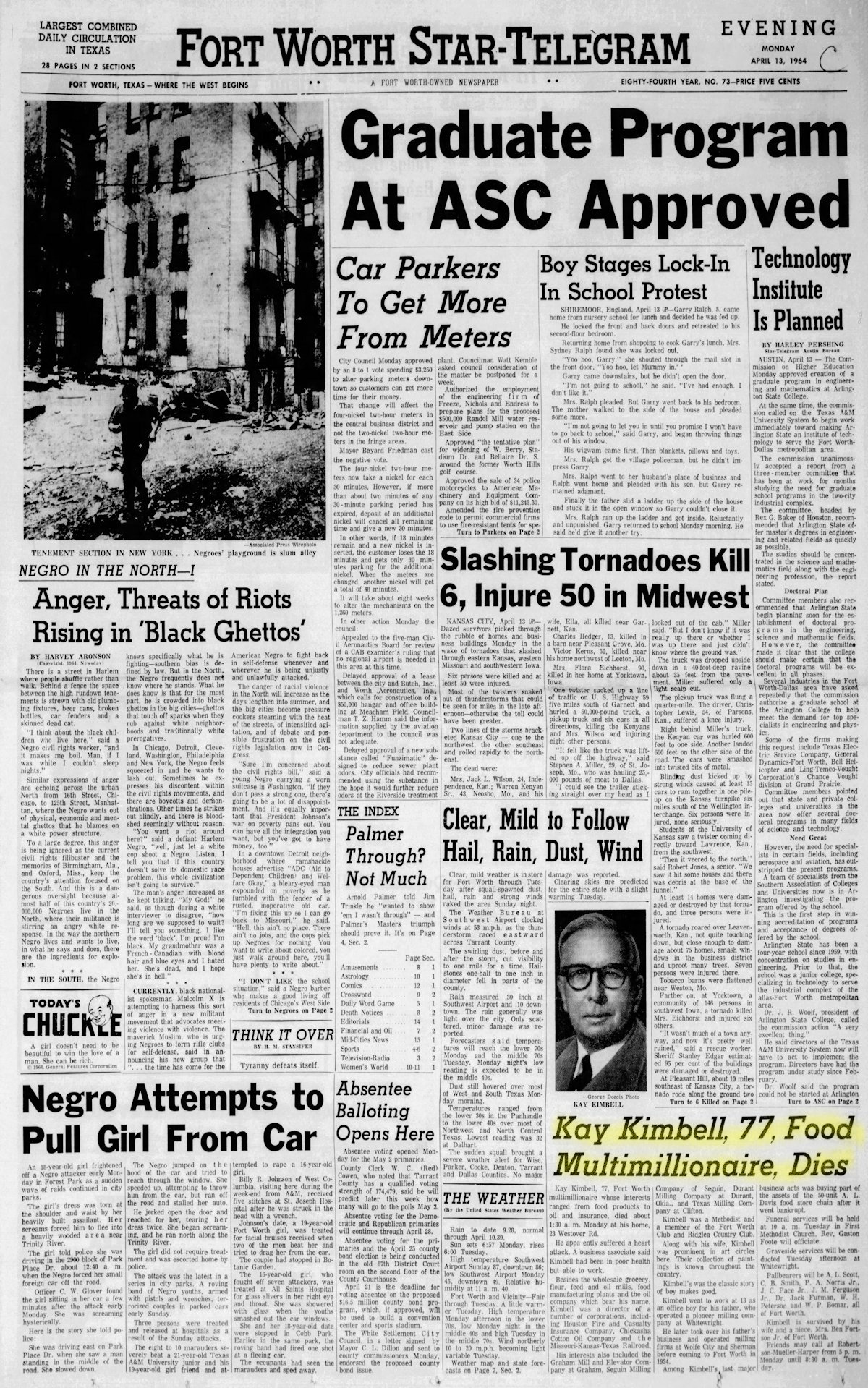

Fast-forward two years. Kay Kimbell died in 1964. He was a millionaire several times over, the head of more than seventy corporations, including feed, flour, and oil mills, an insurance company, grocery chains, and a wholesale grocery company.

Fast-forward two years. Kay Kimbell died in 1964. He was a millionaire several times over, the head of more than seventy corporations, including feed, flour, and oil mills, an insurance company, grocery chains, and a wholesale grocery company.

Kimbell’s will provided funding to build a museum to house the art collection that James Edward Papworth had coveted in 1957.

Kimbell’s will provided funding to build a museum to house the art collection that James Edward Papworth had coveted in 1957.

Fast-forward four years and three thousand miles. By 1968 Papworth was in South America. And Seaman First Class Papworth had left tank landing ships and fleet replenishment oilers behind. Far behind: Authorities in Chile arrested Papworth for using his 110-foot ocean-going motor yacht Dona Decatur, a converted submarine chaser, to smuggle $37,000 worth of electrical appliances. Papworth denied the charges, claimed the cargo was to be legally imported into Bolivia. He was held in custody in a harbor aboard his yacht with wife Betty and his daughter, age nine. But when a Chilean naval officer came aboard to inspect the yacht, Papworth weighed anchor and sailed the Dona Decatur full speed ahead out of the harbor and into open seas, taking the naval officer along.

Now Papworth was charged with kidnapping.

Papworth fled to Peru, where he was again arrested. He was deported to Chile to face kidnapping and smuggling charges. In 1969 he was sentenced to four years by a naval court.

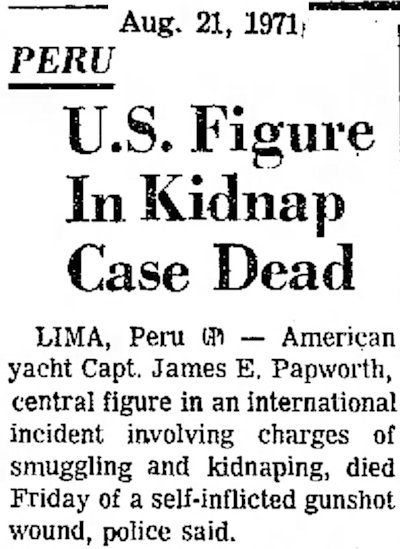

But in 1970 Chilean authorities escorted Papworth to the Chilean-Peruvian border and invited him to never come back. In 1971 he was again arrested in Peru, and his ship was embargoed by Lima shipyard officials for nonpayment of debts. Again Papworth and his wife and daughter were held in custody on his yacht in the port of Lima.

In the end, the greatest threat to James Edward Papworth’s life was not Gene Paul Norris or L. C. Johnson or a jealous husband in New York City or the long arm of the law but rather James Edward Papworth himself. Despondent over his ongoing legal and financial difficulties, on August 19, 1971, as his wife and daughter were on the top deck of the Dona Decatur, Papworth went below deck and shot himself in the head.

In the end, the greatest threat to James Edward Papworth’s life was not Gene Paul Norris or L. C. Johnson or a jealous husband in New York City or the long arm of the law but rather James Edward Papworth himself. Despondent over his ongoing legal and financial difficulties, on August 19, 1971, as his wife and daughter were on the top deck of the Dona Decatur, Papworth went below deck and shot himself in the head.

He was forty-five years old.

Seaman First Class James Edward Papworth, who died on a 110-foot yacht, is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Seaman First Class James Edward Papworth, who died on a 110-foot yacht, is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Much-needed uplifting footnote: In 1985 Papworth’s mother Zanoni was eighty-nine years old, nearly blind, and unable to drive a car. But she continued her long practice of visiting shut-ins in nursing homes and taking food—and flowers from her garden (remember: her husband had been a nurseryman)—to the poor, sick, and disabled.

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade