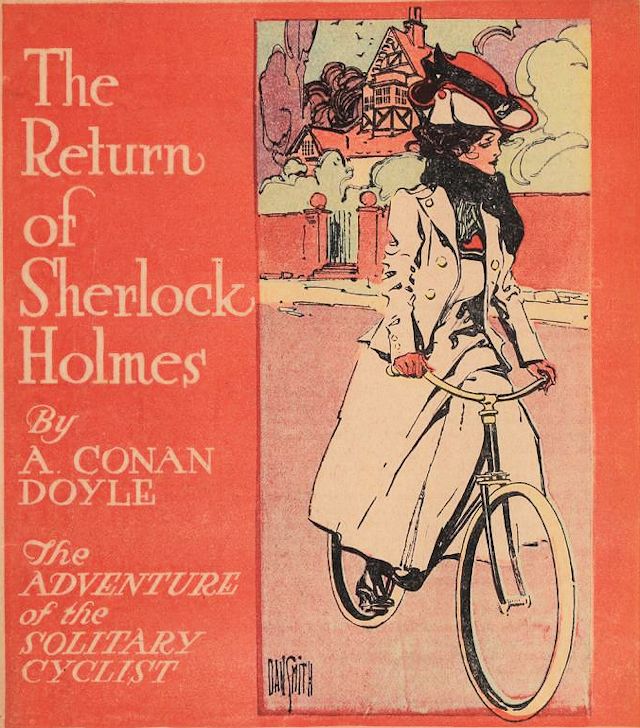

Four years before readers of Arthur Conan Doyle read his “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist” Sherlock Holmes short story, newspaper readers from Montana to South Carolina read about . . .

Four years before readers of Arthur Conan Doyle read his “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist” Sherlock Holmes short story, newspaper readers from Montana to South Carolina read about . . .

the adventure of a solitary cyclist from Fort Worth as she pedaled across the country in search of . . . what?

It was a mystery worthy of the great detective himself. And like many mysteries, it asked as many questions as it answered.

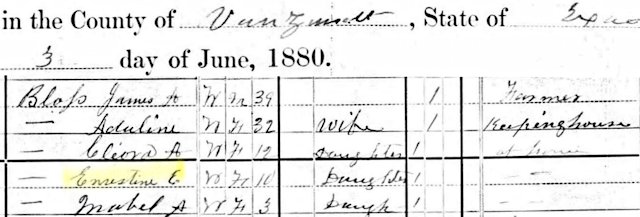

Ernestine (“Ernie”) Bloss was born in Ohio in 1870. By 1880 Ernie and her family were living in Van Zandt County in east Texas.

Ernestine (“Ernie”) Bloss was born in Ohio in 1870. By 1880 Ernie and her family were living in Van Zandt County in east Texas.

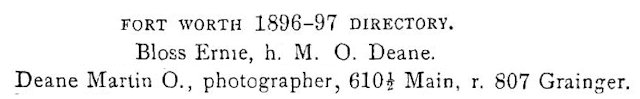

Fast-forward sixteen years. Ernie, now twenty-six, was living with Martin O. Deane, a Fort Worth photographer. She may have been his assistant or apprentice.

Fast-forward sixteen years. Ernie, now twenty-six, was living with Martin O. Deane, a Fort Worth photographer. She may have been his assistant or apprentice.

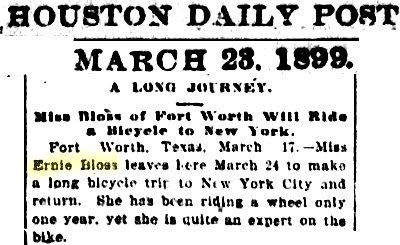

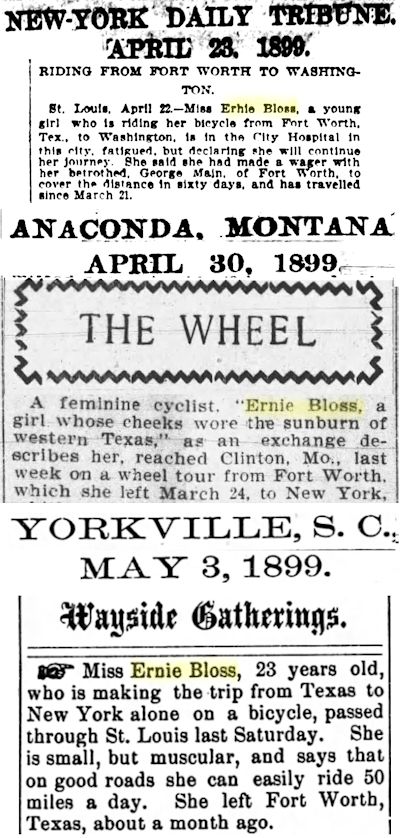

Not much more is known about Ernie Bloss until 1899. In mid-March of that year Ernie Bloss announced that on March 24 she would begin a bicycle trip from Fort Worth to New York City, a distance of more than fifteen hundred miles.

Editions of the Fort Worth Register for the months of March through June 1899 are not available, so we must rely on other newspapers to tell us the Ernie Bloss story.

Before the ubiquity of news syndicates, newspapers relied on an exchange network to gather news from other cities. Here’s how it worked: Newspaper A mailed its editions to newspapers in other cities in the network, which reciprocated by mailing their editions to newspaper A.

So, when on March 23 a story with a March 17 Fort Worth dateline appeared in the Houston Daily Post, the story probably was reprinted from the March 17 Fort Worth Register.

So, when on March 23 a story with a March 17 Fort Worth dateline appeared in the Houston Daily Post, the story probably was reprinted from the March 17 Fort Worth Register.

The story portrayed Ernie Bloss as a pure-dee woman of the West. She was born in Ohio but came to “the plains of west Texas in early childhood.”

“Being accustomed to western life,” the story went on, “she adapted herself to ranch surroundings and learned to brand mavericks and Texas ponies. There never was a broncho so wild that Miss Bloss was not able to conquer and ride.”

Ernie said that on her bicycle trip she planned to follow the Katy railroad tracks from Fort Worth to St. Louis and then the Wabash tracks into Ohio and from Ohio directly to New York City. She said she planned to take photographs and sell them along the way to defray her expenses.

As a news topic Ernie Bloss and her odyssey were a natural. As the nineteenth century ended, bicycling was still all the rage. Long-distance bicycling was challenging. Bicycles had just one speed. There were no bike paths. Heck, there was no pavement. Just dusty, rutted unpaved roads traveled by horses, wagons, buggies, perhaps a few horseless carriages. Also women were not yet pushing the bounds of traditional gender roles and exerting their independence like they would early in the next century. So, a woman bicycling alone was hot copy.

As a news topic Ernie Bloss and her odyssey were a natural. As the nineteenth century ended, bicycling was still all the rage. Long-distance bicycling was challenging. Bicycles had just one speed. There were no bike paths. Heck, there was no pavement. Just dusty, rutted unpaved roads traveled by horses, wagons, buggies, perhaps a few horseless carriages. Also women were not yet pushing the bounds of traditional gender roles and exerting their independence like they would early in the next century. So, a woman bicycling alone was hot copy.

Newspapers called Ernie “the bicycle girl,” “the brave little woman,” the “heroine.”

And did I mention that “the bicycle girl” was packin’ a rod?

The Houston Post wrote of Ernie: “She can handle a Winchester with the dexterity of the old-time plainsman and Indian fighter. . . . She will carry a 38-caliber revolver, which she can, if necessity demands, use with skill.”

Other newspapers latched onto that detail, portraying Ernie as a rolling cowgirl, as Annie Oakley on wheels. For example,

The Sherman Democrat: “Around her waist was a belt filled with cartridges and at her right side hung a scabbard from the top of which appeared the pearl handle of a six-shooter. This particularly attracted the attention of bystanders and there were some amusing conjectures as to what the little woman might be, some saying she must be a United States officer, others that she was a private detective.”

The Sedalia, Missouri Daily Democrat: “She wears a belt with a revolver in plain sight, and her blue dress is plentifully besprinkled with big brass buttons bearing the emblem of the Lone Star state. . . . She said she carried the revolver because if need be she ‘might put up a pretty good bluff.’ She was raised on the plains of Texas, can handle a Winchester, is used to ranch life and uses much slang with unconscious fluency.”

The Jefferson City, Missouri Tribune: “When asked if she ever had occasion to use it [her six-shooter], she said only once . . . when some young fellow got impudent with her and she had to ‘make a bluff at him,’ as she expressed it.”

The Quincy, Illinois Daily Herald: “She is a slight little woman with big blue eyes and brown hair. Her muscles are like iron and her clear blue eyes strengthen the statement she makes when she says she does not know what fear is. Much of her life was passed on a ranch in western Texas, and she can lasso a wild horse or shoot as straight with a rifle as most of the cowboys who travel the boundless Texan plains.”

Remember that as Ernie Bloss bicycled toward New York City, newspapers’ only source for information about Ernie Bloss was Ernie Bloss. Look back at the Houston Post story. “She can handle a Winchester with the dexterity of the old-time plainsman and Indian fighter.” How did the Post know that? Because Ernie told the Post reporter that, and the newspaper printed it as a fact, not a claim, as in “She says she can handle a Winchester with the dexterity of the old-time plainsman and Indian fighter.”

Reporters just jotted down her every word as the gospel according to Ernie.

She was treated as a celebrity and feted in the towns she passed through. Mayors gave speeches, bicycle clubs escorted her, reporters swarmed her. People stared at her six-shooter.

On March 29 the imminent arrival of Ernie made the front page of the Vinita, Oklahoma Chieftain.

On March 29 the imminent arrival of Ernie made the front page of the Vinita, Oklahoma Chieftain.

By April 22 Ernie was in St. Louis. And in the hospital, suffering from fatigue. She had covered eight hundred miles in less than a month, averaging twenty-eight miles a day.

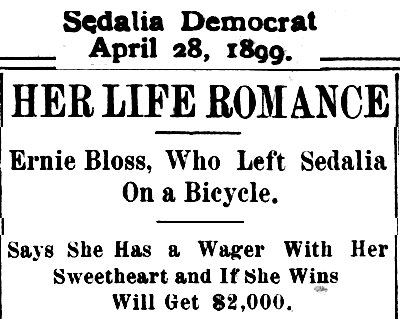

In St. Louis Ernie told reporters how her odyssey came about:

In St. Louis Ernie told reporters how her odyssey came about:

“I am engaged,” she said, “to George Main of Fort Worth, and if all goes well will marry him before the year is out. We have known each other from childhood and have always been sweethearts. When the Spanish[-American] war broke out he joined the Rough Riders and went away with them and was in their very front rank when they did their most gallant fighting in Cuba. While in the island he wrote me many letters and I longed to be at his side and join in the daring acts which he related. When he came back covered with glory and a medal on his breast I was green with envy of him and longed to distinguish myself as greatly as he had done. Shortly after arriving in Fort Worth Mr. Main developed a fever which he had contracted while in the ditches in front of Santiago. His mother and I nursed him through the long, tiresome siege, and when he finally recovered he asked me to become his wife.

“All went well for a time, but at last George became proud of the adulation he received from his relatives and friends and would jestingly ask me why I did not do a daring thing and become famous like he was. These taunts annoyed me, and one evening I conceived the idea of riding to Washington [she earlier had said New York City] on my wheel [her bicycle]. I have been an enthusiastic wheeler ever since I was a mere girl and can ride for days without fatigue. When I told my family of my determination they threw up their hands in horror and said I could never do it. My mind was made up, however, and so here you see me as a result. I told my fiance of my plan and he laughed at the idea, but, seeing I was determined, promised to give me $2,000 [$63,000 today] in cash if I accomplished the feat and said that the coin would be waiting for me in Washington. He stipulated, however, that I must cover the ground in sixty days. I took to the road on March 24 and made good progress right from the start. The spring air was delicious and I enjoyed every inch of the way until I crossed the Missouri line. . . . The men in the little towns were rude to me and stared at me as if I were a curiosity.”

She also bemoaned the roads she traveled: “The roads! Well, they are at present like furrows plowed by a green plow boy. I am surprised that I have been able to come this far without even having punctured a tire.

“The worst experience I had was out here in California [a town in Missouri]. I arrived one evening and was leaving next morning when a crowd of tramps, who had been dogging my steps for several hours, stepped into the road when I was a few miles from town and ordered me to stand and deliver. I stopped my wheel and, springing to the ground, drew my 38-caliber revolver and commanded them to depart at once. They at first showed no inclination to do this and one of the ruffians started to advance towards me. I fired a shot over their heads which came near enough, however, to apprise them that I meant what I said, and the entire gang fled to the woods.”

Note these details about her story: Ernie said she and George Main had known each other since childhood, he had returned from the war covered in glory, she nursed him back to health, they were engaged to be married, and he had promised to pay her $2,000 if she bicycled from Fort Worth to Washington, D.C. in sixty days or less.

Got all that?

Good.

Now forget all that.

Because Ernie Bloss was about to change her story.

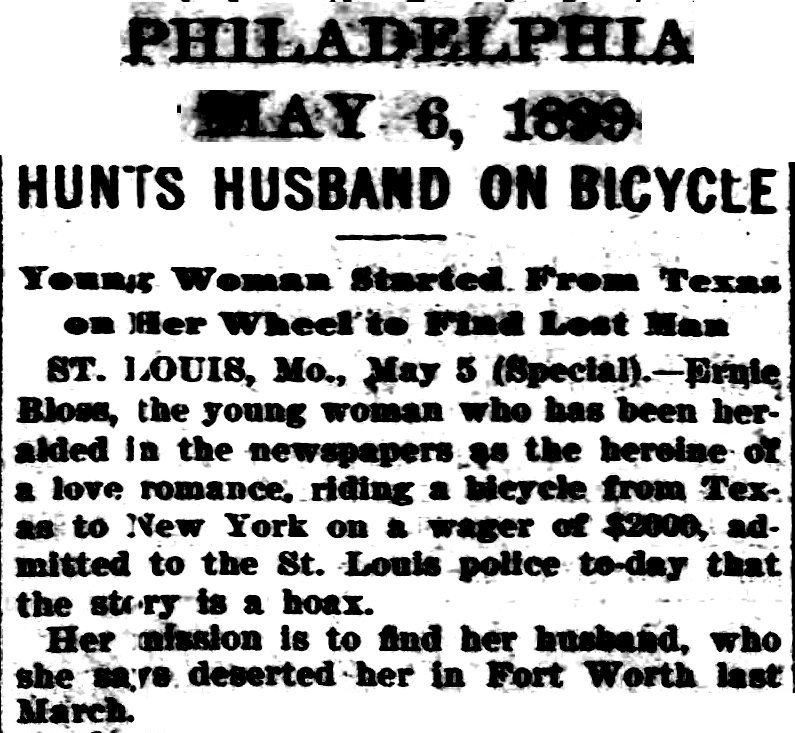

On May 6 the Philadelphia newspaper said Ernie admitted to St. Louis police that her story was a hoax.

On May 6 the Philadelphia newspaper said Ernie admitted to St. Louis police that her story was a hoax.

Ernie gave the St. Louis Post-Dispatch a new story:

“I was living on a big ranch near Odessa, Texas and was as happy as a girl could be. I had my own horse and the free life of the ranch was what I loved. A stranger [George Main] came along. He was wealthy, he said, and was traveling for pleasure. He was only about 25 years old, and dressed exquisitely. He had curling brown hair and dark eyes. His hands were as soft as a woman’s. I cared nothing for him at first, and his attentions annoyed me. He was only going to remain at Odessa a few days, but he tarried. He did no work and remittances came regularly to him.”

(Ernie said Main told her he had wealthy relatives in Albany, New York.)

“He was so persistent in his attentions to me that I learned to await his comings. Finally I consented to marry him. He left and went to Fort Worth. . . . Then he wrote for me to come to Fort Worth. I went there, and on May 18 we were married in the Memorial church by the Rev. Dr. Morris. We boarded at the Tremont hotel, the best the city afforded.

“His remittances ceased coming, and he employed Andrew H. Jackson, the lawyer, . . . to write for him to New York and discover what was amiss. Jackson did considerable writing and got a lot of names and addresses, but my husband told me he wanted to go to New York himself, but he would have to go in disguise. He said a friend of his had killed a man there and they wanted him [her husband] for a witness. He had the initials ‘R.W.M.’ tattooed on his arm. There was a big scar on the left side of his neck, seven buckshot were in his right side and a rifle ball wound was on his right thigh. He left and asked me to keep quiet about it.

“I tried to get track of my husband but could not. I got one letter from him. That was from Roodhouse, Illinois. In looking through his clothes once I found a letter from a woman, who signed herself Minnie Robinson, at Quincy [Illinois]. This letter showed me that she was also his wife and that they had a little boy. I decided to go in search of him. I had no money on which to undertake so big a journey, so I dressed in this rig, and, in order to deceive him, I had to deceive the public. I gave it out that I was going to Washington, D.C., to meet my lover, and was to get $2,000 for making the trip on my wheel. This was printed in the newspapers. I figured that he would see this and in the hopes of getting the $2,000 he would hunt me up.

“I will go from here to Quincy. I will hunt up this Robinson woman, and if she has been wronged by him and will assist me we will work together. I will find him if I have to ride a day a century for the next year.”

So, in her new account, Ernie had only recently met Main, she “cared nothing for him at first,” she and Main had married, she had not nursed him back to health after he became ill fighting in the Spanish-American War. And now her destination was Quincy, not Washington or New York City.

So, in her new account, Ernie had only recently met Main, she “cared nothing for him at first,” she and Main had married, she had not nursed him back to health after he became ill fighting in the Spanish-American War. And now her destination was Quincy, not Washington or New York City.

Note that in her new account she explained her motivation for her first account: “I gave it out that I was going to Washington, D.C. to meet my lover and was to get $2,000 for making the trip on my wheel. This was printed in the newspapers. I figured that he would see this and in the hopes of getting the $2,000 he would hunt me up.”

Huh? In her first account, Main, as her “lover,” was going to give her $2,000 if she won the wager. Why would he “hunt me up” to get the money he had not yet given her?

When she had been bicycling to win a wager, newspapers saw Ernie as a plucky “little woman.” When she announced that she was bicycling to find an errant husband, newspapers saw Ernie as a wronged woman—a wronged woman with a six-shooter. Her human interest value ticked up.

When she had been bicycling to win a wager, newspapers saw Ernie as a plucky “little woman.” When she announced that she was bicycling to find an errant husband, newspapers saw Ernie as a wronged woman—a wronged woman with a six-shooter. Her human interest value ticked up.

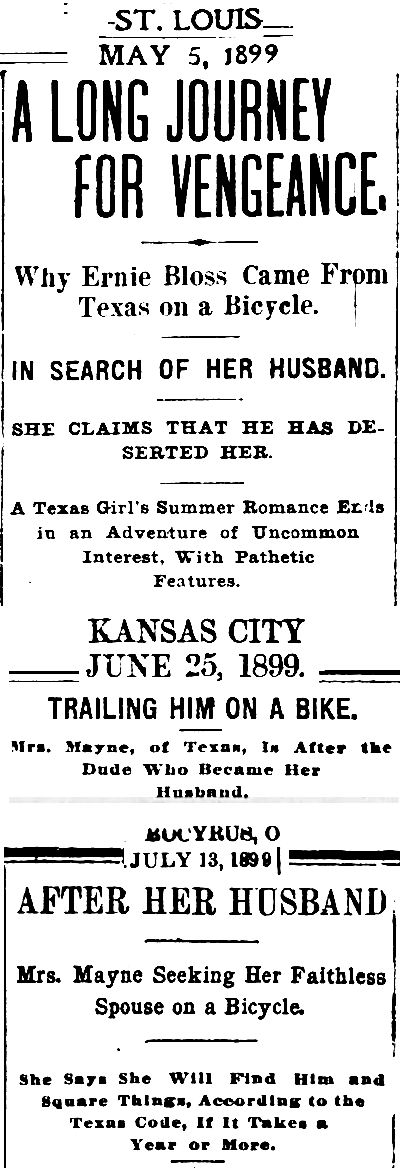

Now Ernie Bloss was on a “Long Journey for Vengeance” “on a Bike” to “Square Things” against her “Faithless Spouse.”

On May 5 the Topeka, Kansas State Journal reported that Ernie “intimated that when she finds the man [Main] she will shoot him.”

Another report said she intended to “make trouble.”

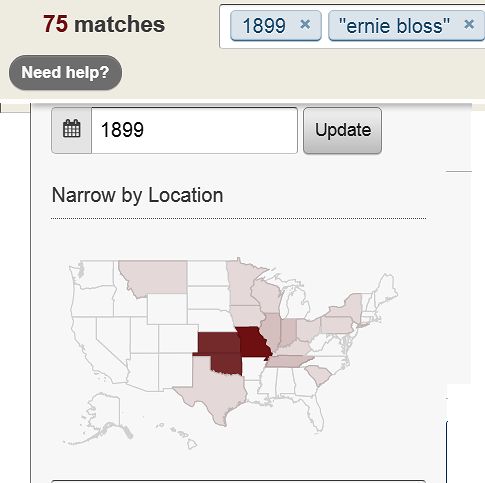

During five months twenty newspapers in nineteen states—mostly the states she passed through or planned to pass through—had printed seventy-five stories about first Ernie Bloss the solitary cyclist and then Ernie Bloss the wronged woman. Sixty-two of those stories were printed after she changed her account! Ernie Bloss knew how to make headlines.

During five months twenty newspapers in nineteen states—mostly the states she passed through or planned to pass through—had printed seventy-five stories about first Ernie Bloss the solitary cyclist and then Ernie Bloss the wronged woman. Sixty-two of those stories were printed after she changed her account! Ernie Bloss knew how to make headlines.

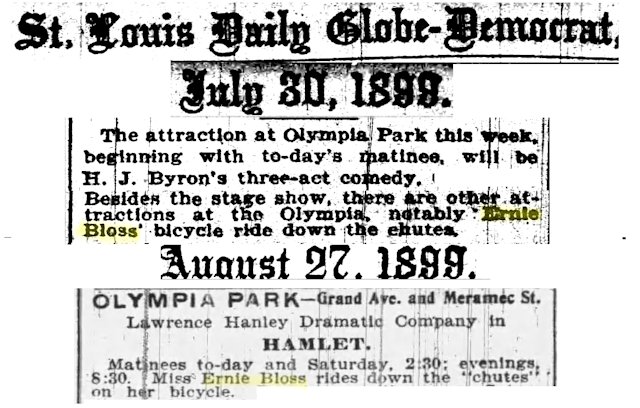

But at the end of July Ernie abruptly fell out of the news. In the month of August her name appeared in newspapers only in an ad: She was performing on her bicycle in an amusement park in St. Louis. She had been in St. Louis—one hundred miles from Quincy, eight hundred miles from New York—more than four months.

But at the end of July Ernie abruptly fell out of the news. In the month of August her name appeared in newspapers only in an ad: She was performing on her bicycle in an amusement park in St. Louis. She had been in St. Louis—one hundred miles from Quincy, eight hundred miles from New York—more than four months.

Beginning with the July 6, 1899 issue, the Fort Worth Register is available and searchable for the rest of the year, but it contains no coverage of the plucky hometown heroine.

Why did Ernie Bloss suddenly fall out of the news?

That is the biggest question of all. Even if she changed her mind about pursing her husband, finding the other Mrs. Main, or continuing her bicycle trip, that decision in itself would have been newsworthy to newspapers who had hung on her every word and deed.

Here’s an easier question. First she said Main was her fiancé. Then she said he was her husband. Which was he?

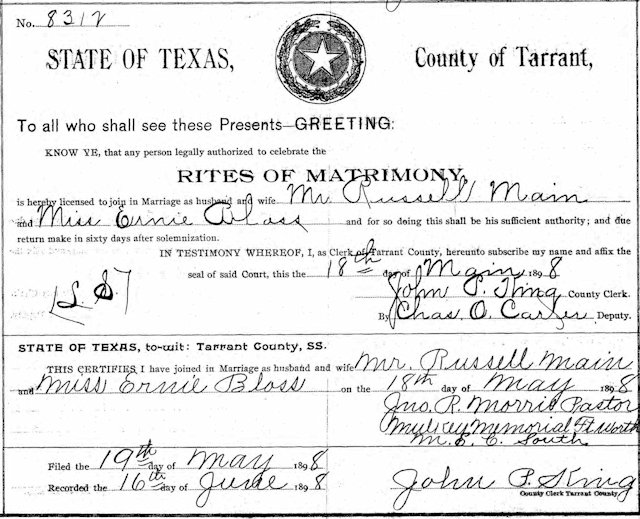

Turns out Ernie was telling the truth in her second account. She and Russell Main were married in Mulkey Memorial Methodist Church in Fort Worth in 1898.

Turns out Ernie was telling the truth in her second account. She and Russell Main were married in Mulkey Memorial Methodist Church in Fort Worth in 1898.

So, whereas Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist” is about a woman cyclist who is followed by a man, is Ernie Bloss’s adventure about a woman cyclist who followed a man?

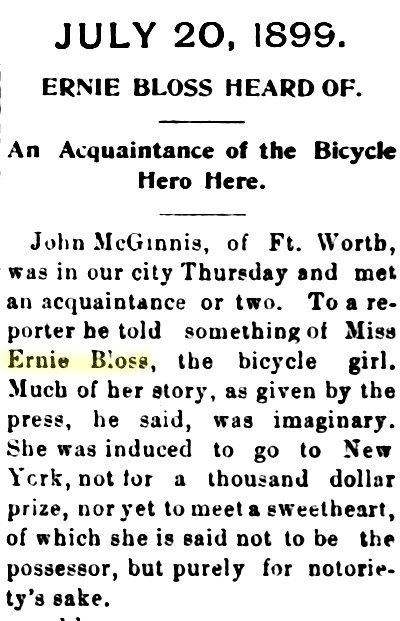

Maybe. In July the Vinita Chieftain interviewed John McGinnis as he passed through town. The newspaper described McGinnis as an acquaintance of Bloss. After talking with McGinnis, the newspaper wrote: “Much of her story, as given by the press, he said, was imaginary. She was induced to go to New York, not for a thousand dollar prize, nor yet to meet a sweetheart, of which she is said not to be the possessor, but purely for notoriety’s sake.”

Maybe. In July the Vinita Chieftain interviewed John McGinnis as he passed through town. The newspaper described McGinnis as an acquaintance of Bloss. After talking with McGinnis, the newspaper wrote: “Much of her story, as given by the press, he said, was imaginary. She was induced to go to New York, not for a thousand dollar prize, nor yet to meet a sweetheart, of which she is said not to be the possessor, but purely for notoriety’s sake.”

Oh, say it ain’t so, Ernie! The “bicycle girl, “the brave little woman” a mere attention-seeker, a Victorian Kardashian?

If McGinnis’s claim was true, it’s possible that newspapers realized they had been “taken in” by Ernie and dropped her, but in that era of Yellow Journalism, would they have let her prevarication deprive them of a good story, no matter how dubious? Recall how newspapers two years earlier had printed the most dubious claims during Airship April.

Did she ever reach Quincy, her last stated destination?

Apparently not. If a woman with Ernie Bloss’s knack for self-promotion had found the other Mrs. Main, she would have made sure that newspapers knew about it.

Did she ever find her husband?

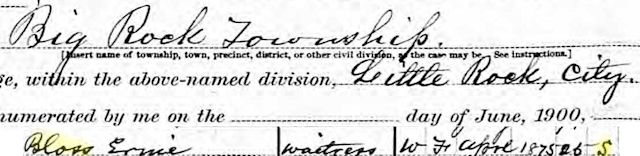

If she did, it was only to lose him again—for good. In 1900 she was a waitress in Little Rock, using her maiden name and listed in the census as single.

What became of Ernie Bloss after 1900?

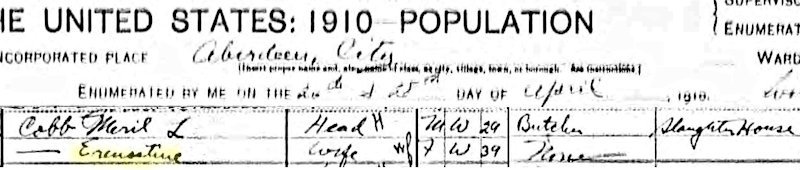

By 1910 Ernie Bloss Main was Mrs. Meril Cobb, living in Washington state. Mr. Cobb was a butcher in a slaughterhouse.

By 1910 Ernie Bloss Main was Mrs. Meril Cobb, living in Washington state. Mr. Cobb was a butcher in a slaughterhouse.

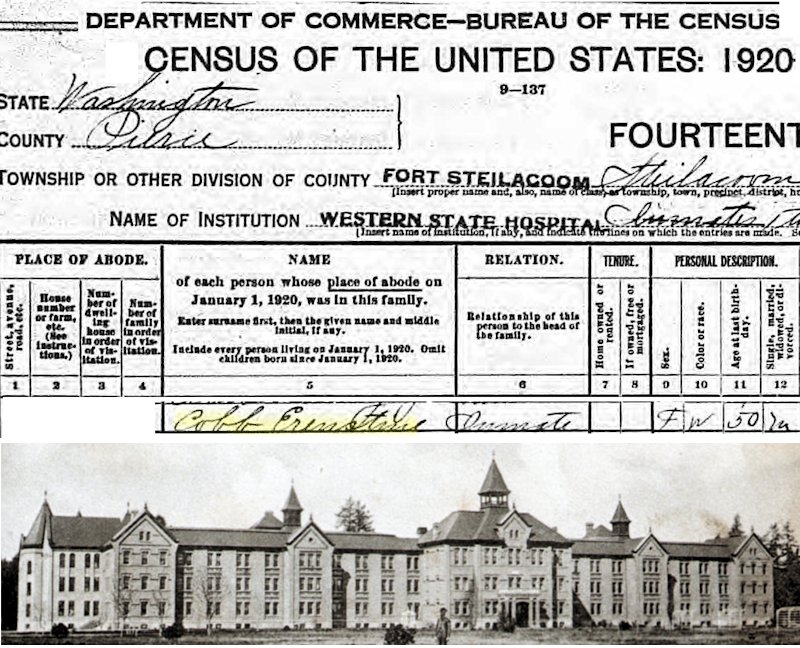

Fast-forward to 1920. Now a bemusing story becomes a sad story. Mrs. Meril Cobb was still living in Washington state but now as an inmate of the Western State Hospital for the Insane. She was listed as “married.” (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Fast-forward to 1920. Now a bemusing story becomes a sad story. Mrs. Meril Cobb was still living in Washington state but now as an inmate of the Western State Hospital for the Insane. She was listed as “married.” (Photo from Wikipedia.)

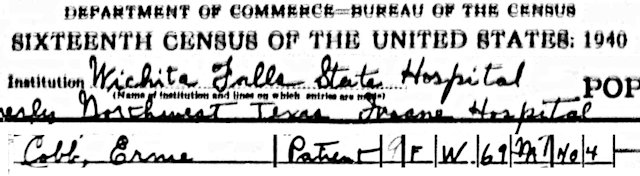

Fast-forward twenty more years. In 1940 Ernie was a patient at Wichita Falls State Hospital for the mentally ill. She had been there since about 1928.

Fast-forward twenty more years. In 1940 Ernie was a patient at Wichita Falls State Hospital for the mentally ill. She had been there since about 1928.

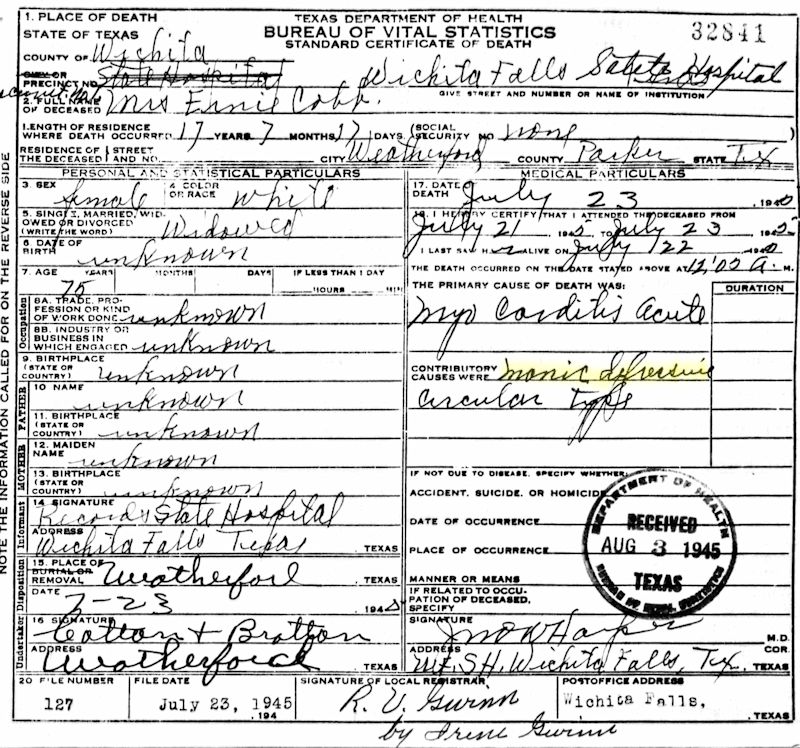

Ernie Bloss died at the Wichita Falls hospital in 1945. She was seventy-five years old and a widow. Her death certificate lists “manic depressive” as a contributory cause of death.

Ernie Bloss died at the Wichita Falls hospital in 1945. She was seventy-five years old and a widow. Her death certificate lists “manic depressive” as a contributory cause of death.

Mrs. Ernestine Cobb, the “little woman” who enjoyed a summer of celebrity as the solitary cyclist, is buried in Zion Hill Cemetery in Parker County under a marker provided by the funeral home. (Photo from Find a Grave.)

Mrs. Ernestine Cobb, the “little woman” who enjoyed a summer of celebrity as the solitary cyclist, is buried in Zion Hill Cemetery in Parker County under a marker provided by the funeral home. (Photo from Find a Grave.)

(Thanks and a tip of the deerstalker to Fort Worth history detective Donna Humphrey Donnell.)

Posts About Women in Fort Worth History