By the time three girls went to Seminary South mall in December 1974 and were never seen again, Carla Walker had been dead ten months.

Her murder case would remain unsolved for forty-seven years.

During that time parents and siblings of the victim would die. Likewise, original investigators in the case would die or retire. The crime scene—a bowling alley—would later house an ice rink, a wedding venue, a mortgage company.

And all the while the science of forensics would grow ever more sophisticated.

By the time the Carla Walker cold case was cracked, it would feature psychics, false leads and false confessions, a wrongful conviction, anonymous telephone calls, a cryptic letter, and, most of all, tenacity by two generations of Fort Worth police investigators.

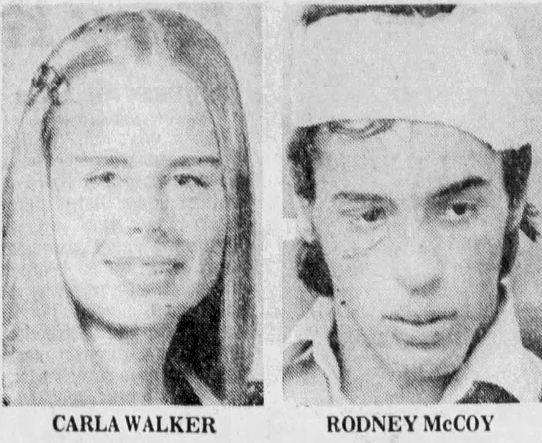

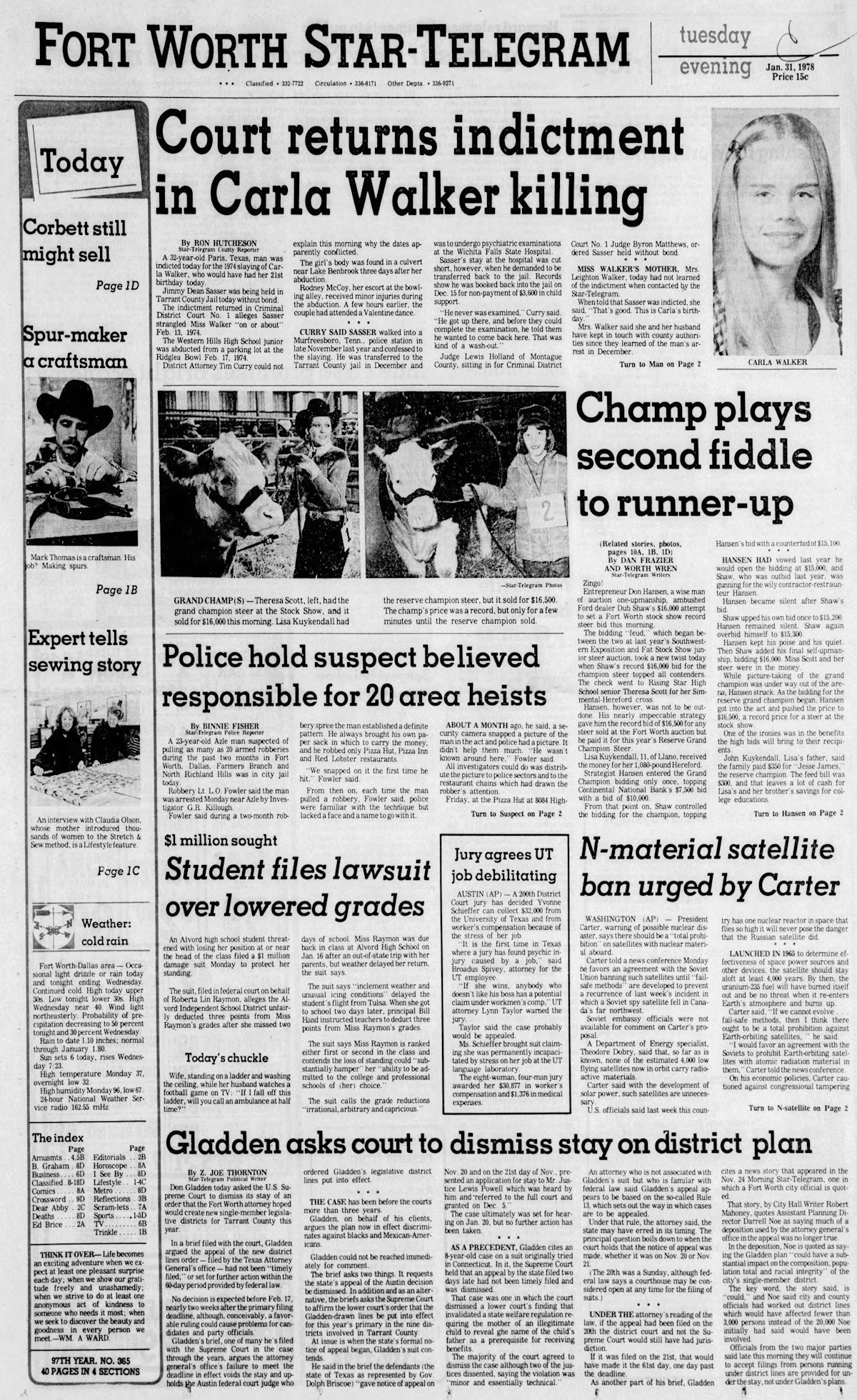

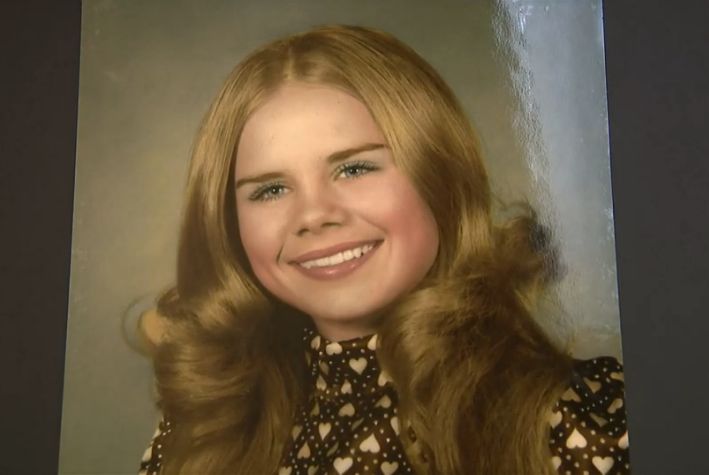

Carla Walker was seventeen, a petite 4-foot-11 junior at Western Hills High School. She was a cheerleader and tennis team member. Her boyfriend, Rodney McCoy, eighteen, was a Western Hills senior, captain and quarterback of the varsity football team.

The couple had been dating about a year by 1974. McCoy planned to attend Texas Tech University in Lubbock, and Carla planned to follow him. McCoy had given Carla his promise ring.

She was wearing that ring on the night of February 16, 1974 as the couple attended a Valentine’s dance at the school. Carla was wearing a powder blue prom dress with white ruffles.

After the dance ended, Carla and Rodney drove in his mother’s big Ford LTD car to a few WHHS hangouts and then parked in the lot behind Brunswick Ridglea Bowl on the Benbrook traffic circle.

Carla and Rodney were kissing in the dark when the front passenger door was suddenly jerked open. Then Carla was screaming and Rodney was being beaten on the head with a pistol butt.

McCoy later recalled: “Carla was screaming, ‘Quit hitting him,’ so my assumption, he hit me several times. Blood was just flowing down in my eyes and my face and everything, and it was like I was paralyzed.”

Then the attacker aimed the pistol at Rodney’s face and began pulling the trigger.

The gun misfired repeatedly.

McCoy recalled that Walker screamed, “Go get my dad.”

As the attacker pulled Carla from the car Rodney lost consciousness.

When Rodney regained consciousness, Carla was gone. On the parking lot asphalt were her purse, McCoy’s promise ring, and the magazine of a Ruger .22-caliber pistol.

One mile away on Williams Road, Carla Walker’s brother Jim, twelve, had stayed up late as his parents played dominoes. About 1:40 a.m. Jim heard a car tire scrape the curb in front of the house. Then Rodney McCoy was pounding on the front door and yelling, “They got her!”

When the Walkers opened the door, in the illumination of the porch light they saw Rodney’s beaten face.

The Walkers telephoned police. Mr. Walker grabbed a gun and sped away to look for his daughter.

He didn’t find her that night, and neither did police.

Rodney McCoy told police that Carla’s abductor was a white man standing about 5 feet 10 and weighing about 175 pounds. McCoy said that the abductor had brown hair, cropped in a military fashion, and wore a brown cowboy hat. He might have been driving a light-colored Camaro.

At dawn police, friends, and neighbors began to search for Carla on foot and horseback, in cars and a helicopter. Western Hills High students held a prayer vigil.

At dawn police, friends, and neighbors began to search for Carla on foot and horseback, in cars and a helicopter. Western Hills High students held a prayer vigil.

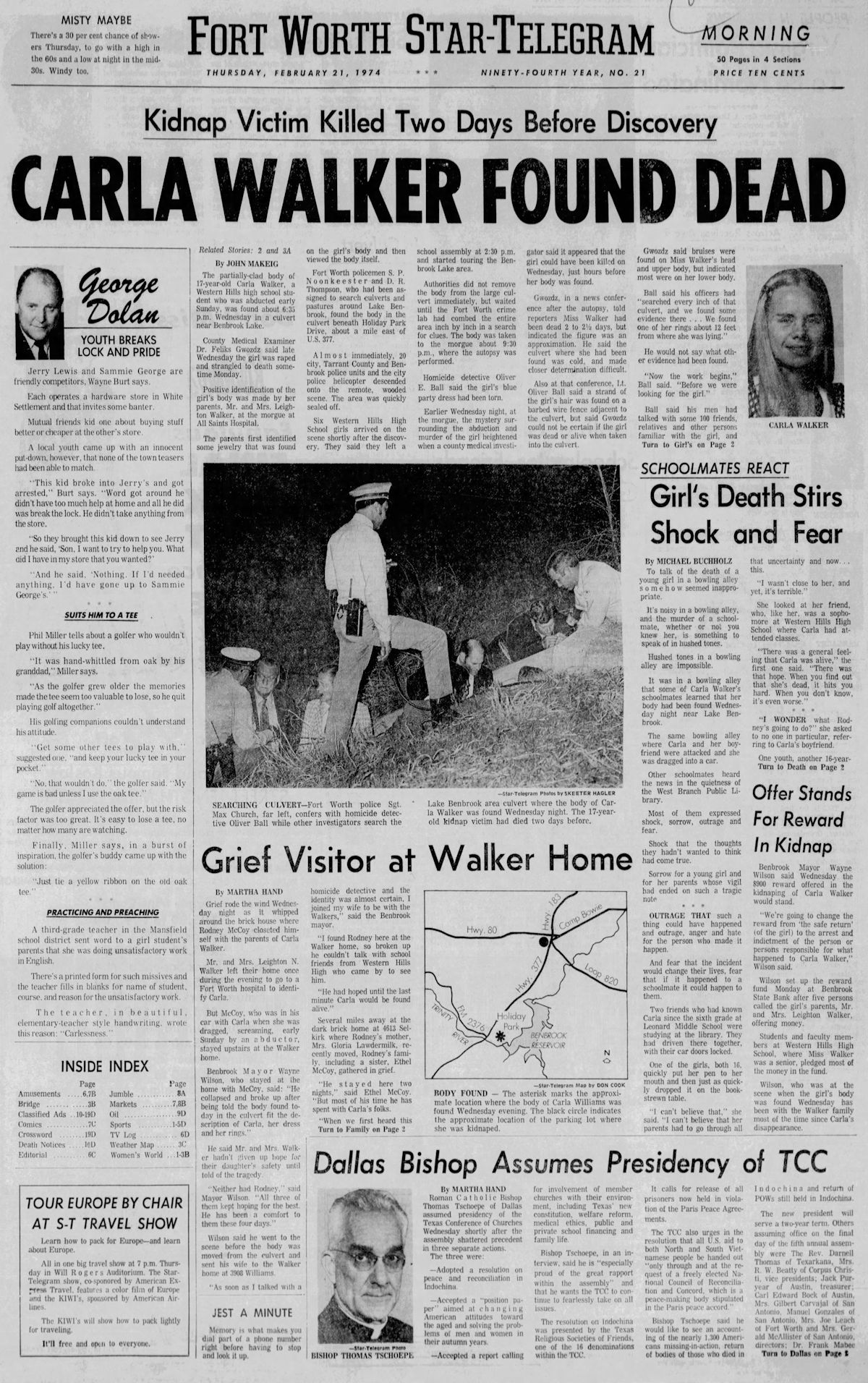

On February 20 police found Carla Walker’s partially clad body in a culvert near Benbrook Lake. She had been beaten, raped, and strangled.

On February 20 police found Carla Walker’s partially clad body in a culvert near Benbrook Lake. She had been beaten, raped, and strangled.

Fort Worth lab technicians found semen on Walker’s underclothing, but forensic science in 1974 could not glean much information from such evidence.

Fort Worth lab technicians found semen on Walker’s underclothing, but forensic science in 1974 could not glean much information from such evidence.

Two hours after Carla Walker’s body was found, a psychic in North Carolina telephoned the Star-Telegram. He predicted that Carla’s body—clad in formal attire—would be found about thirty miles from downtown Fort Worth. He said the killer drove a “hopped-up car” resembling a Mustang with a black and white top and a custom-painted maroon bottom. He described the killer as being about 5 feet 10, weighing 145-155 pounds with a small waist.

Two hours after Carla Walker’s body was found, a psychic in North Carolina telephoned the Star-Telegram. He predicted that Carla’s body—clad in formal attire—would be found about thirty miles from downtown Fort Worth. He said the killer drove a “hopped-up car” resembling a Mustang with a black and white top and a custom-painted maroon bottom. He described the killer as being about 5 feet 10, weighing 145-155 pounds with a small waist.

The Star-Telegram quoted the psychic: “The killer wore dungarees and had a belt with some type of silver doodads about every inch around his waist. He wore a white T-shirt, a cowboy hat, had a thin face, high cheekbones, not much of a beard, and was immature looking with red rimmed eyes.”

The psychic predicted the case would be solved by the end of the week.

It wasn’t. Not even close.

A few days after Carla was buried, her parents began to receive phone calls.

Mrs. Walker told the Star-Telegram: “Sometimes they come every week, sometimes every two weeks, sometimes in the morning and sometime in the afternoon and whoever it is who’s calling never says a word. We always say, ‘Hello! Hello! Hello!’ and they never answer. As much as a minute will pass, and it’ll always be a dead silence on the other end.”

The calls continued through 1975.

One of the few clues police had was the Ruger .22-caliber pistol magazine. Police began to question people who owned such pistols. One of those people was Glen Samuel McCurley, who lived less than two miles from the bowling alley. McCurley told police that his pistol had been stolen about six weeks earlier—about the time Walker was killed. He said he did not report the theft because he was an ex-convict.

As an eighteen-year-old McCurley, then a resident of Westview Boys Home in Oklahoma, had stolen a car—from a bowling alley—and led police on a 130-mile high-speed chase until they shot out his tires. He had then fled on foot until he was captured. He had been sentenced to two years in Huntsville prison.

As an eighteen-year-old McCurley, then a resident of Westview Boys Home in Oklahoma, had stolen a car—from a bowling alley—and led police on a 130-mile high-speed chase until they shot out his tires. He had then fled on foot until he was captured. He had been sentenced to two years in Huntsville prison.

Meanwhile in 1974, after Carla Walker’s boy was found Benbrook State Bank established a reward fund of $10,000 for information leading to the conviction of her killer, but in late 1975 the fund expired, and the money was returned to contributors.

Also in 1975 the Walker family had a clairvoyant flown in from New York. Mrs. Walker told the Star-Telegram: “He said there’s a person in Fort Worth who knows who did it . . . there was a dark person involved in it. Not a black but maybe a Latin American . . . He said he thinks [Carla] was kept [in the area around the culvert where the body was found] for the four days she was missing. . . .”

The year 1975 also brought the first identified suspect in the case. Euless carpet layer Tommy Ray Kneeland had been sentenced to 550 years in prison for one murder and to two life sentences for two other murders. He also faced trial in Fort Worth for aggravated kidnapping of a sixteen-year-old Arlington girl. Fort Worth investigators hoped that Kneeland would confess to the Carla Walker murder after Rodney McCoy identified Kneeland as his attacker and Carla’s abductor.

The year 1975 also brought the first identified suspect in the case. Euless carpet layer Tommy Ray Kneeland had been sentenced to 550 years in prison for one murder and to two life sentences for two other murders. He also faced trial in Fort Worth for aggravated kidnapping of a sixteen-year-old Arlington girl. Fort Worth investigators hoped that Kneeland would confess to the Carla Walker murder after Rodney McCoy identified Kneeland as his attacker and Carla’s abductor.

Nothing came of that lead.

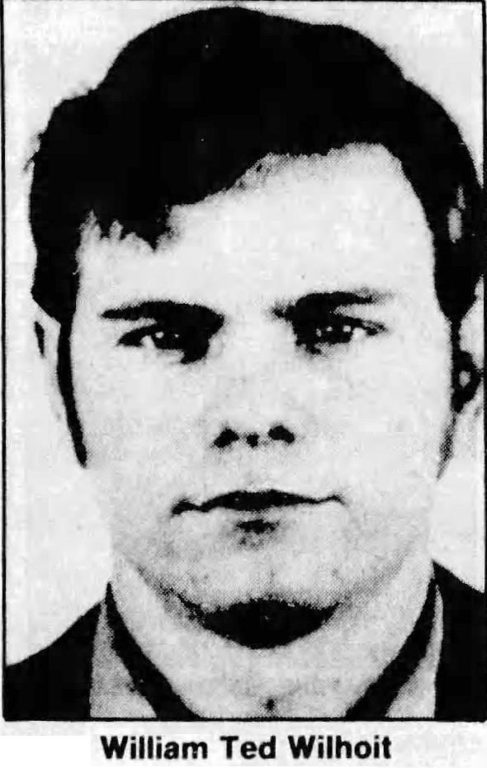

That same year Fort Worth police burglary detective John F. Terrell went to the home of William Ted Wilhoit to arrest him for a series of burglaries. When Terrell arrived at Wilhoit’s house, Wilhoit was standing in his front yard.

Terrell recalled: “I called him over to the car and he got in. First thing he said was, ‘I wondered when you were coming after me for Carla Walker.’”

Terrell recovered stolen property from Wilhoit’s house and took him to jail.

Terrell decided to press Wilhoit about his remark about Carla Walker.

Terrell recalled: “I talked to him about Carla, how she was from a good family. I fed on his conscience. I told him he wouldn’t be able to live with himself, so he might as well tell me if [he] killed her.”

Wilhoit began to cry. Again Terrell suggested that Wilhoit ease his conscience and confess. “He was crying heavily, and I’ll never forget it. He said, ‘Well, I guess I might as well,’” Terrell recalled.

But just then, Terrell recalled, someone pounded on the door of the interview room. Terrell was needed elsewhere.

He was denied the confession he felt he was close to getting.

Police returned to Wilhoit’s house and found a leaflet on Ruger firearms.

Terrell said of Wilhoit: “We found where he had pawned Rugers before.”

Suggestive but insufficient to bring a charge.

Soon after, Terrell got Wilhoit sentenced to Huntsville for burglary.

In 1976 an employee of the Brunswick Ridglea Bowl picked Wilhoit’s photo out of a lineup, indicating Wilhoit had been in the bowling alley on the evening of the Carla Walker abduction in 1974.

Three days later Terrell drove to Huntsville prison, where Wilhoit was given a polygraph test regarding the Walker murder. Wilhoit denied the crime but failed the test. Afterward, Terrell recalled, Wilhoit explained that he had failed the test in the Walker case because of its similarity to another case for which he could never be prosecuted. Terrell inferred that Wilhoit was implying that he was guilty of the attempted murder of TCU student Janelle Kirby, also in 1974.

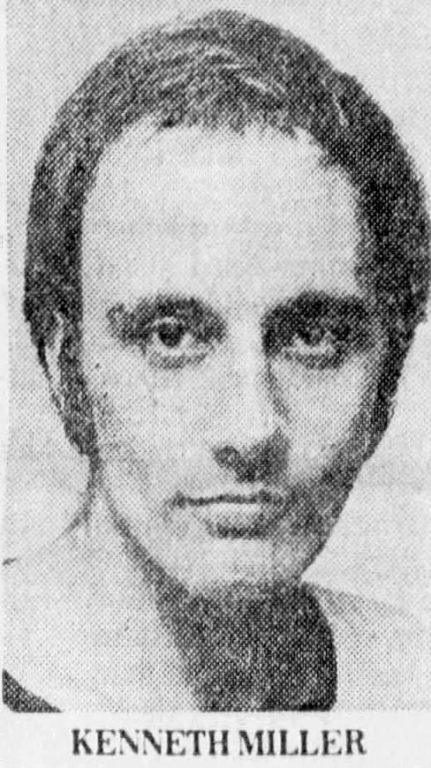

Another man, Kenneth Leslie Miller, had been convicted—wrongfully—in the Kirby case but in 1975 had slipped out of the courthouse and gone on the lam before he could be sentenced and imprisoned.

Another man, Kenneth Leslie Miller, had been convicted—wrongfully—in the Kirby case but in 1975 had slipped out of the courthouse and gone on the lam before he could be sentenced and imprisoned.

In 1977 Terrell’s suspicion of Wilhoit in the Walker case seemed to evaporate when Jimmy Dean Sasser of Paris, Texas walked into the police department in Murfreesboro, Tennessee and confessed to killing Carla Walker. In 1978 he was indicted for the crime.

In 1977 Terrell’s suspicion of Wilhoit in the Walker case seemed to evaporate when Jimmy Dean Sasser of Paris, Texas walked into the police department in Murfreesboro, Tennessee and confessed to killing Carla Walker. In 1978 he was indicted for the crime.

In addition to his confession, Sasser gave police a statement detailing how he abducted and killed Carla Walker. But his statement was so riddled with inaccuracies and omissions that Fort Worth police began to grow skeptical.

In addition to his confession, Sasser gave police a statement detailing how he abducted and killed Carla Walker. But his statement was so riddled with inaccuracies and omissions that Fort Worth police began to grow skeptical.

Detective George Hudson told the Star-Telegram: “You can quote me saying, ‘He didn’t do it.’”

Indeed Sasser later recanted his confession and said he had been depressed over the breakup of his marriage and under the influence of cocaine when he walked into the police station in Murfreesboro.

Back to square 1.

In 1986 the Carla Walker murder turned twelve years old, and detective John F. Terrell retired. The case was cold, although Terrell continued to suspect William Ted Wilhoit.

In 1990, at Terrell’s request Fort Worth police reopened the Carla Walker cold case to determine whether Wilhoit, by then in prison for raping a woman while he was a Bible student, might have killed Walker. That lead, like the others, led nowhere, and in 1992 Wilhoit was released from prison.

Fast-forward ten years. In 2002 John F. Terrell, now retired for sixteen years, created a website to solicit leads in the Carla Walker cold case.

Terrell died in 2010. In 2017 a Facebook group, Justice for Carla Walker, was created.

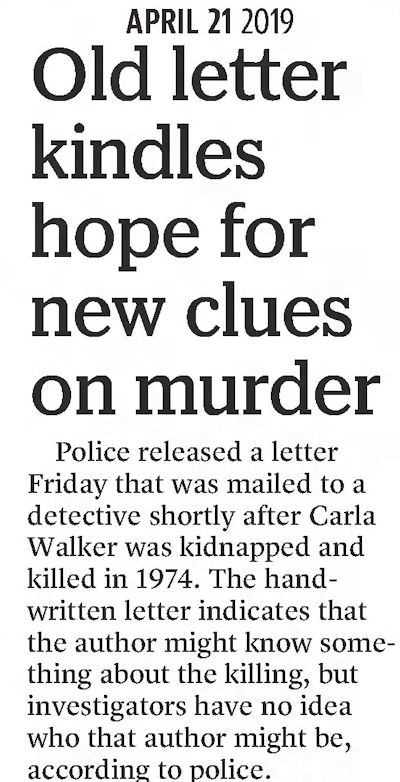

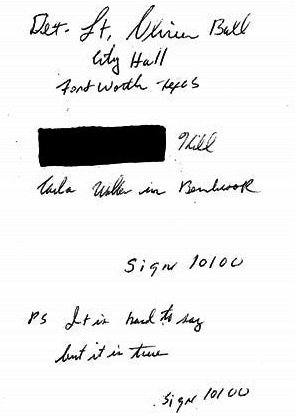

Fast-forward to 2019. Police reopened the Carla Walker cold case yet again and discovered that shortly after Carla’s murder in 1974 detective Oliver Ball had received an anonymous letter. Ball died in 1983 without sharing the letter with the public or Walker’s family.

Fast-forward to 2019. Police reopened the Carla Walker cold case yet again and discovered that shortly after Carla’s murder in 1974 detective Oliver Ball had received an anonymous letter. Ball died in 1983 without sharing the letter with the public or Walker’s family.

In 2019 police, hoping that the letter would cause someone with knowledge of the crime to come forward, published a redacted version of the letter on social media. The letter read in part: “kill Carla Walker in Benbrook Sign 10100” and “PS It is hard to say but it is true Sign 10100.”

In 2019 police, hoping that the letter would cause someone with knowledge of the crime to come forward, published a redacted version of the letter on social media. The letter read in part: “kill Carla Walker in Benbrook Sign 10100” and “PS It is hard to say but it is true Sign 10100.”

Carla’s brother Jim said of the letter, “Someone knows something. The author of this letter clearly wants to get something off their chest. It’s time for somebody to do the right thing and step forward.”

No one stepped forward.

Meanwhile Carla’s friends told the story of her murder to Paul Holes, the detective who had used the latest in forensics—DNA evidence—to crack the Golden State Killer case and convict Joseph James DeAngelo Jr., who committed at least thirteen murders, fifty rapes, and 120 burglaries across California between 1973 and 1986. Holes hosted a TV show, The DNA of Murder, on the Oxygen channel.

Fast-forward to 2020 and the forty-sixth year of the Carla Walker murder case. The case had become an heirloom: The first generation of investigators (John F. Terrell, George Hudson, Oliver Ball) had bequeathed the mystery to the next generation.

Among that next generation were Leah Wagner and Jeff Bennett, who had been knee high to a search warrant when Carla Walker was killed. Wagner and Bennett, who constitute the police department’s cold case unit, reopened the case. In 2020 they had access to forensic science that would have seemed like science fiction to Terrell et al. in 1974.

In April 2020 Paul Holes aired an episode of The DNA of Murder about the Carla Walker case. Detectives Wagner and Bennett gave Holes access to their police files and physical evidence.

Since 1974 the Fort Worth police department had preserved physical evidence in one of its coldest cold cases, including Carla Walker’s underclothing. Such evidence must be stored at low temperature to slow deterioration.

Holes’s show paid for advanced DNA testing of the underclothing. Analysts at the Serological Research Institute in California uncovered male DNA from three stains on Carla’s underclothing that had not been successfully read before. But the DNA profile did not link to anyone on CODIS, a law enforcement database that contains the DNA of millions of criminals.

Holes’s next attempt to get a lab to create a genealogical profile also failed.

The Star-Telegram wrote that Holes told Fort Worth police about Othram, a forensic genealogy lab near Houston. Using state-of-the art parallel DNA sequencing, Othram reconstructed the DNA sample’s genome. Othram then uploaded the data from the sample onto GEDmatch, an online service to compare autosomal DNA data files from different testing companies. Othram got a match with a person who may have been a distant relative and constructed a family tree to trace the distance between the DNA on GEDmatch and the DNA sample. That trace led to three brothers with the surname “McCurley.”

Othram CEO David Mittelman telephoned detective Bennett with the good news. “Imagine our surprise,” Mittelman said, “when we discover . . . he [Bennett] recognizes the name”—”McCurley,” the Ruger pistol owner who had been interviewed by police in 1974.

Detective Wagner said of McCurley: “He was suspicious [in 1974] because of the weapon he had and proximity of where he lived. They [police] just didn’t have enough [evidence].”

Three days later Fort Worth police collected items from a trash cart at McCurley’s curb. DNA test results from the items matched the male profile that Othram had helped police to identify from Carla’s underclothing. Wagner and Bennett then interviewed McCurley. McCurley denied that he had killed Carla Walker or knew her. He again claimed, as he had in 1974, that his Ruger pistol had been stolen. But he agreed to provide a DNA sample from his mouth. That sample also matched the DNA found on Carla’s underclothing, the Star-Telegram wrote.

Glen Samuel McCurley was arrested, without incident, on September 21, 2020. He was charged with capital murder.

Detective Wagner said police also recovered the Ruger pistol that McCurley claimed had been stolen in 1974.

Asked what McCurley had been doing for the last forty-six years, Jeff Bennett said, “He’s been working here locally and just living a very normal life.”

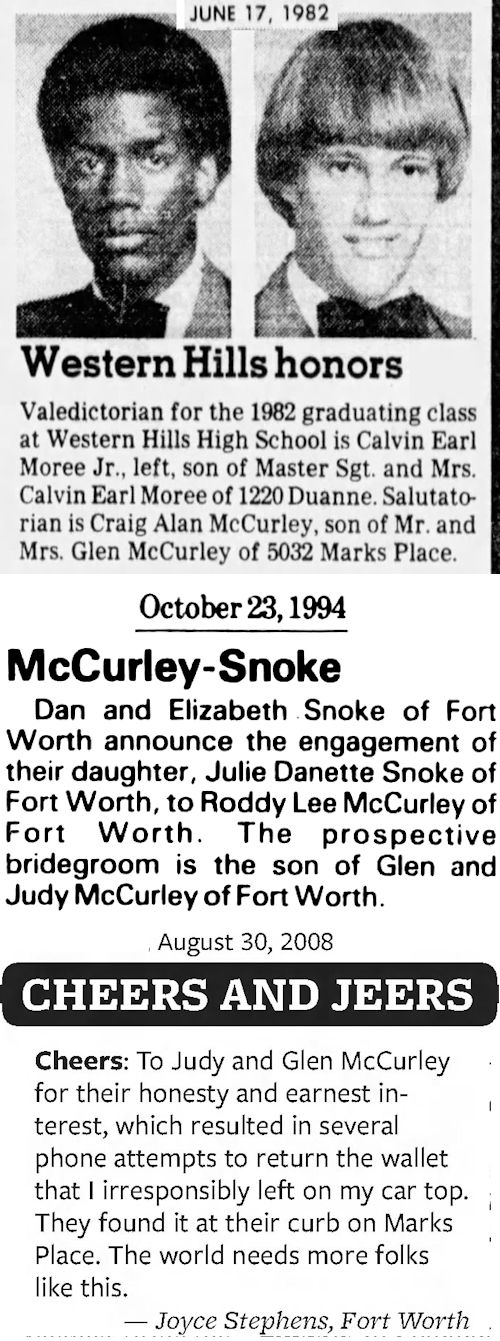

Normal indeed. The McCurleys—Glen and wife Judy—raised a salutatorian at Western Hills High School, where Carla Walker had been a junior in 1974. They celebrated the marriage of another son. They were “cheer”ed in the Star-Telegram by a woman for returning her lost wallet.

Normal indeed. The McCurleys—Glen and wife Judy—raised a salutatorian at Western Hills High School, where Carla Walker had been a junior in 1974. They celebrated the marriage of another son. They were “cheer”ed in the Star-Telegram by a woman for returning her lost wallet.

In 2020 after McCurley’s arrest he was interviewed in jail by a local radio station. He claimed that he did not kidnap Walker but rather interrupted an assault and saved her from her boyfriend. McCurley said that on the night of February 16, 1974—his eleventh wedding anniversary—he was driving around drinking when he saw Carla Walker and Rodney McCoy sitting in a car behind the bowling alley.

“He [McCoy] was hitting on her, and I was drinking beer in the parking lot,” McCurley said. “And I saw him [McCoy]. He was screaming. And I went over there and opened the door, and knocked him off of her” and “pulled” Carla to his car.

“We talked for a while, and she calmed down,” McCurley told the radio station. “And she said she was thankful for me getting him away from her. . . . She just gave me a hug. I gave her a kiss. I mistook her [hug] for something else. I didn’t mean to do it.”

Friends of both McCoy and Walker disputed McCurley’s claim that McCoy would abuse Walker.

Police said they also obtained a confession from McCurley.

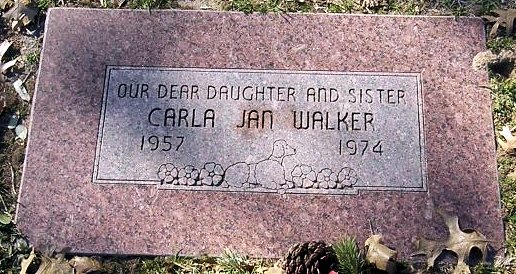

With the arrest of McCurley, Carla Walker’s brother Jim discovered that Carla and McGurley’s son Craig, who had been killed in 1988, were buried in the same section of the same cemetery—a thirty-second walk separating the two graves.

That proximity made Jim wonder about flowers he used to find on Carla’s grave. He asked close friends and family members about the flowers but never found out who had left them.

Jim Walker said of McCurley: “We are praying for you. We don’t hate you. We really are praying for you. I hope that the city of Fort Worth has prayers for the family. It’s not their fault.”

In May 2021 Tarrant County prosecutors announced that they would not seek the death penalty against McCurley, by then seventy-eight and in poor health. If convicted he would face a maximum sentence of life in prison.

Glen McCurley pleaded not guilty at a pretrial hearing on June 16.

On August 19 the capital murder trial of Glen Samuel McCurley began in a courtroom that seemed too small to contain forty-seven years of grief and frustration. On August 20 the first witness called was Carla’s boyfriend in 1974, Rodney McCoy.

McCoy is now sixty-five years old.

He told the jury that he and Carla were parked behind the bowling alley on that night in 1974. Carla was leaning back against the front passenger door when suddenly a man jerked the door open, causing Carla to fall partially out of the car. McCoy testified that a man beat him on the head with the butt of a pistol and grabbed Carla.

McCoy recalled: “It was such an intense ringing, I was totally stunned. I couldn’t move. I pushed myself up, blood was flowing. I was staring straight ahead.”

McCoy said that before he blacked out Carla pleaded with him:

“Rodney, go get Dad. Go get my dad.”

McCoy said those were the last words he heard Carla Walker speak.

When he regained consciousness, she was gone.

As McCoy testified, Glen McCurley (pictured) sat in a wheelchair twenty feet away. (Image from KXAS-TV.)

Police and sheriff’s officers, now retired, testified about their role in the investigation in 1974.

Police detective Leah Wagner took the stand and identified the clothing of Carla Walker and Rodney McCoy, preserved since 1974.

Detective Wagner displayed the shirt that Rodney McCoy wore on the night of the abduction. (Image from KXAS-TV.)

Wagner told the jury how she and detective Bennett reopened the cold case in 2019 and how application of today’s forensic science led police back to McCurley, whom the first generation of detectives had interviewed in 1974.

Jurors also listened to an audio recording of Wagner and Bennett interviewing McCurley and his wife to obtain a sample of his DNA.

McCurley’s defense attorneys questioned the handling of the crime scene by investigators, the validity of the forensic evidence, and the admissibility of McCurley’s confession.

On the second day of testimony forensic scientist Mallory Pagenkopf testified about DNA analysis of stains found on Carla’s clothing. Pagenkopf said that in one instance the chance that a particular stain came from a person other than Glen McCurley is 1 in 28 octillion (28 followed by twenty-seven zeros).

Detective Bennett also testified. He told jurors that the cold case unit has almost one thousand cases, the oldest from 1959. He said that the unit receives little funding from the city and that the producers of the television series The DNA of Murder agreed to provide $15,000 for the DNA testing in the Carla Walker case.

Bennett recalled that he was at home in bed on the morning of July 4, 2020 when he got a phone call from Othram CEO David Mittelman.

“They told me that they had developed a full profile, genealogical, working that they had a family name. He [Mittelman] told me that the name that they had developed was ‘McCurley.’ And that was a very emotional moment because I felt like I was hearing something that detectives had wanted to hear for the last forty-six years.”

Testifying about events in the bowling alley parking lot on the night of February 16, 1974, Bennett said that when McCurley hit Rodney McCoy with the butt of his pistol, the pistol’s magazine—housed in the grip—became detached and fell to the parking lot. The significance of that detail was twofold. First, Bennett said, it probably explains why the pistol just clicked when McCurley pointed it at McCoy and pulled the trigger. Second, it gave investigators a major clue—a clue that led them to Glen McCurley in 1974. In 2020 DNA testing would bring investigators back to a name from forty-six years earlier: “McCurley.”

On the courtroom projection screen the jury also watched a video recording of Wagner and Bennett interviewing McCurley after his arrest in 2020. In a small interview room Wagner told McCurley that she and Bennett wanted to give him a chance to tell his side.

The interview lasted almost three hours. In the beginning McCurley denied the charge against him. When Wagner placed a photo of Carla Walker on the table in front of McCurley, he said, “Never seen her, never met her, would not know her if she was standing beside me.” (Image from Fort Worth PD.)

The interview lasted almost three hours. In the beginning McCurley denied the charge against him. When Wagner placed a photo of Carla Walker on the table in front of McCurley, he said, “Never seen her, never met her, would not know her if she was standing beside me.” (Image from Fort Worth PD.)

He contended he was a suspect in the crime only because he had owned a Ruger that matched the magazine found at the abduction scene.

“I haven’t killed anybody,” he told Wagner and Bennett.

Wagner listened patiently and then advised McCurley to tell the truth.

“Everything you told me right now stinks to high heaven,” she said.

Wagner told McCurley that the DNA evidence was conclusive.

“Tell us about it. I promise you’ll feel better.”

Detectives Wagner and Bennett comforted McCurley as he began to sob. (Image from Fort Worth PD.)

Detectives Wagner and Bennett comforted McCurley as he began to sob. (Image from Fort Worth PD.)

McCurley then gave his account of that night, which essentially paralleled the account he had given in his interview with the radio station.

But eventually, at the urging of Wagner and Bennett, McCurley went further, admitting that he killed Carla Walker after raping her.

His voice trembling, McCurley said, “I choked her to death, I guess. I didn’t beat her up. . . .

“I’m guilty.”

“Of what?” detective Bennett asked.

“That little girl.”

McCurley said he killed Carla because he feared she “would tell on me.”

After confessing, McCurley was temporarily left alone in the interview room. On the table in front of him was the photo of Carla Walker. (Image from Fort Worth PD.)

After confessing, McCurley was temporarily left alone in the interview room. On the table in front of him was the photo of Carla Walker. (Image from Fort Worth PD.)

Spectators in the courtroom sat silently during the emotional interview. Some left the courtroom in tears.

As the trial was about to resume on August 24, 2021 Glen Samuel McCurley, after a day of damning testimony, waived his right to a jury trial and changed his plea to guilty. Judge Elizabeth Beach sentenced him to life in prison for the capital murder of Carla Walker.

Justice had come forty-seven years, six months, and eight days after a girl in a powder blue prom dress disappeared from behind a bowling alley.

After McCurley was sentenced, Carla’s sister Cindy Stone addressed McCurley from the witness stand.

After McCurley was sentenced, Carla’s sister Cindy Stone addressed McCurley from the witness stand.

“I wish you had done this a long time ago,” Stone told McCurley. “You had choices, lots of choices that night. You went out to kill somebody. You had your gun, you had your alcohol, you had your whiskey, and you’re still not telling the truth about everything you did. . . . I want to know if you’ve done this to anybody else, you need to bring that out, because those families need to know, too. You have nothing to lose at this point. Because it’s been hell.” (Image from KXAS-TV.)

Carla’s brother Jim Walker said, “This was a lot of healing going on in here today. Not just for me and my family but for the whole community.”

Rodney McCoy said of McCurley, “He hung a cloud of suspicion on me for all those years. I mean, that’s torment. It’s torment to live that.”

Carla’s parents and some of the first generation of detectives in the case did not live to see justice prevail, but the next generation of detectives had closed one of Fort Worth’s coldest cold cases.

As spectators filed out of the courtroom on August 24, many of them hugging in a release of emotion, the final image projected on the courtroom screen was a photo of Carla Walker. (Image from KXAS-TV.)

As spectators filed out of the courtroom on August 24, many of them hugging in a release of emotion, the final image projected on the courtroom screen was a photo of Carla Walker. (Image from KXAS-TV.)

Carla Jan Walker is buried in Greenwood Cemetery. She would be sixty-five this year.

Carla Jan Walker is buried in Greenwood Cemetery. She would be sixty-five this year.

(Thanks to retired Fort Worth police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster for his help.)

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

It’s good to know the end of that mystery. But the first sentence of your post mentions the other big mystery of 1974, the Seminary South girls. Will we ever know that end?

In 1975, I was still working at Mid-Cities, waiting to hear from any of 5 school districts I had applied to teach. The Christmas before, a photographer went across the street from the office to the Hurst Christian Church where the youth group was selling Christmas trees. He took several pictures, and of course, we used one that had kids in it, looking at the trees. One of the pix he had was of a young man who was flocking a tree. Dutiful as he was, the photog got names of everyone in each picture. Those extras went into a drawer. When the two (IIRC Oklahoma) teenagers were found dead in the bottoms and the FWPD identified an arrested suspect as Tommy Ray Kneeland, the name clicked with the photog…a hurried search of the drawers where unused pix were kept found the pic of Kneeland, the flocker….We were excited that we had it and ran it the next day…One of the few times MCDN was actually current (as I’m sure you remember) ….Another reporter there was roommate with a Press police reporter….She said it was quite frosty around their house for several days…LOL….

What a great story of the old MCDN days, Dan.