How do you react to the image below?

Do you react viscerally? Negatively, with thoughts of Hitler, Nazi Germany, the Holocaust, World War II? When we react negatively, it’s because we see this symbol through post-1930s eyes. But if you could screw a pair of pre-1930s eyes into your sockets (kids, don’t try this at home), you’d probably see the swastika neutrally if not downright positively. That’s because for most of the last three thousand years the swastika as a symbol has had a positive connotation, as it does in Buddhism and Hinduism, and has symbolized good luck or auspiciousness (the meaning of the word swastika in Sanskrit).

Do you react viscerally? Negatively, with thoughts of Hitler, Nazi Germany, the Holocaust, World War II? When we react negatively, it’s because we see this symbol through post-1930s eyes. But if you could screw a pair of pre-1930s eyes into your sockets (kids, don’t try this at home), you’d probably see the swastika neutrally if not downright positively. That’s because for most of the last three thousand years the swastika as a symbol has had a positive connotation, as it does in Buddhism and Hinduism, and has symbolized good luck or auspiciousness (the meaning of the word swastika in Sanskrit).

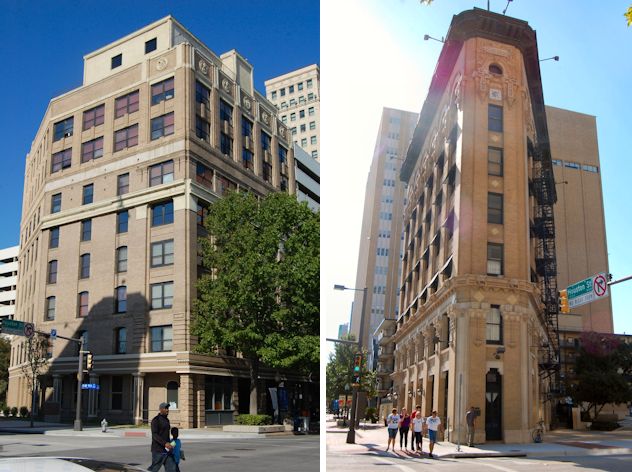

For example, locally the swastika as a symbol of auspiciousness seems to have been especially popular in 1906-1907. That’s when these two buildings—(left) Western National Bank Building and (right) Flatiron Building—bearing swastikas were built downtown. The swastikas were placed at the entrances of the two buildings, as if to bestow good luck upon all who enter.

For example, locally the swastika as a symbol of auspiciousness seems to have been especially popular in 1906-1907. That’s when these two buildings—(left) Western National Bank Building and (right) Flatiron Building—bearing swastikas were built downtown. The swastikas were placed at the entrances of the two buildings, as if to bestow good luck upon all who enter.

In 1906, if you had walked into the new Western National Bank Building of William Eddleman (as in the Ball-Eddleman-McFarland House on Penn Street in Quality Hill) at 9th and Houston streets) swastikas would have been over your head as you entered. The bank was organized on February 3, 1904.

In 1906, if you had walked into the new Western National Bank Building of William Eddleman (as in the Ball-Eddleman-McFarland House on Penn Street in Quality Hill) at 9th and Houston streets) swastikas would have been over your head as you entered. The bank was organized on February 3, 1904.

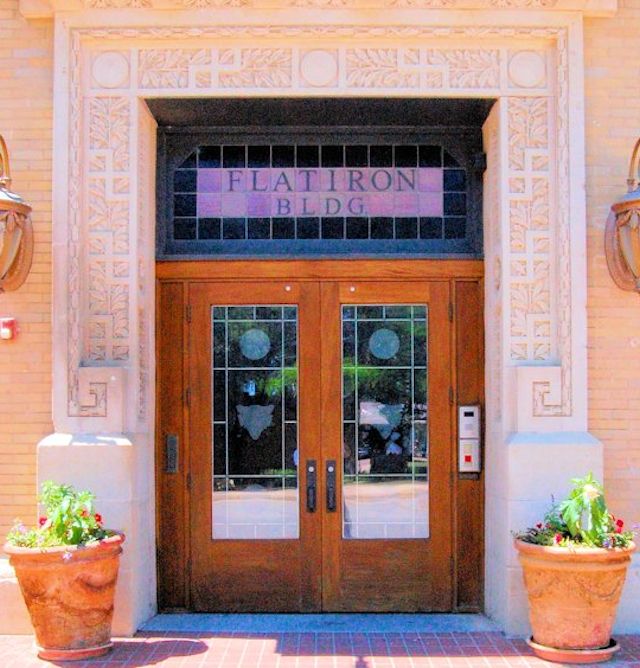

In 1907, if you had walked into Dr. Bacon Saunders’s new Flatiron Building across 9th Street from Eddleman’s bank, swastikas would have been at your sides and overhead.

In 1907, if you had walked into Dr. Bacon Saunders’s new Flatiron Building across 9th Street from Eddleman’s bank, swastikas would have been at your sides and overhead.

Both buildings were designed by Sanguinet and Staats.

Swastikas appeared in architecture in American buildings early in the twentieth century, sometimes as freestanding symbols, sometimes, as used by Sanguinet and Staats, in rows between parallel bands.

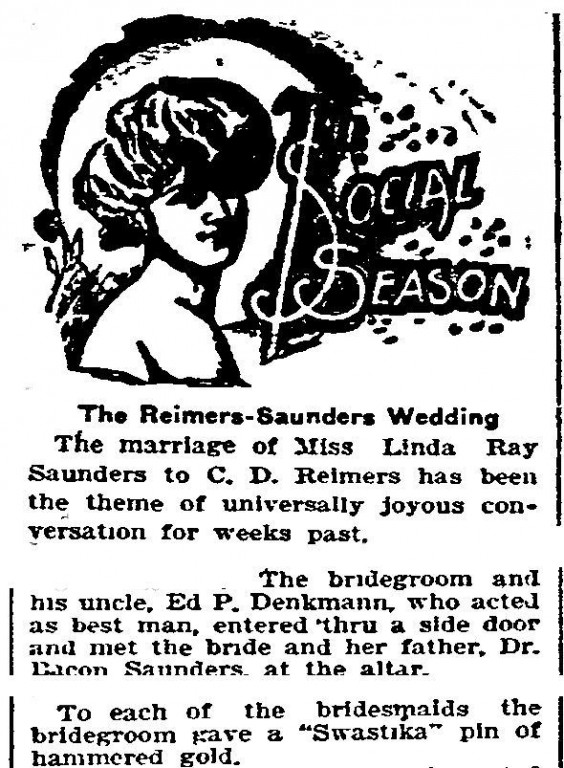

In fact, swastikas were featured at the wedding of Dr. Saunders’s daughter in 1906. Saunders was dean of Fort Worth Medical College. His wife was a founder of the Fort Worth chapter of the Society for the Prevention of Useless Giving.

In fact, swastikas were featured at the wedding of Dr. Saunders’s daughter in 1906. Saunders was dean of Fort Worth Medical College. His wife was a founder of the Fort Worth chapter of the Society for the Prevention of Useless Giving.

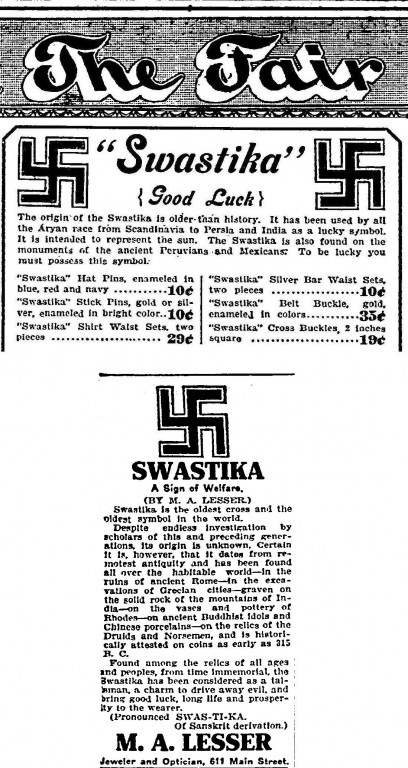

The swastika at the top of this post is from these ads in the Fort Worth Telegram in 1907. If you had walked into The Fair woman’s department store downtown in 1907, you would have seen swastika belt buckles and swastika hat pins. Likewise, local jeweler M. A. Lesser touted the advantages of swastika jewelry.

The swastika at the top of this post is from these ads in the Fort Worth Telegram in 1907. If you had walked into The Fair woman’s department store downtown in 1907, you would have seen swastika belt buckles and swastika hat pins. Likewise, local jeweler M. A. Lesser touted the advantages of swastika jewelry.

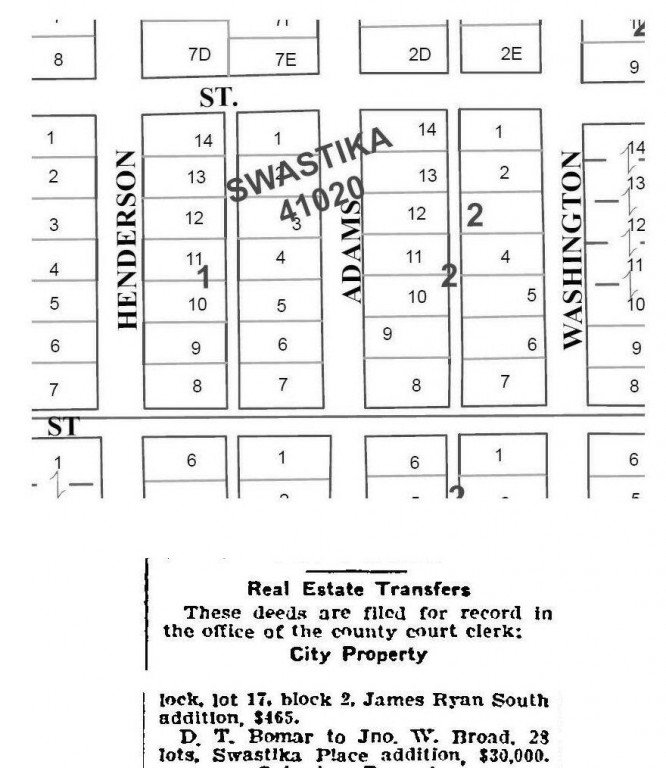

And if you had gone home to this planbook house (1912) at 1404 South Adams in Fairmount, you would have been living in one of the first houses built in the Swastika Place subdivision.

And if you had gone home to this planbook house (1912) at 1404 South Adams in Fairmount, you would have been living in one of the first houses built in the Swastika Place subdivision.

David T. Bomar (1861-1917), local attorney, banker, and developer, developed Swastika Place and probably named it. Again the year was 1907.

David T. Bomar (1861-1917), local attorney, banker, and developer, developed Swastika Place and probably named it. Again the year was 1907.

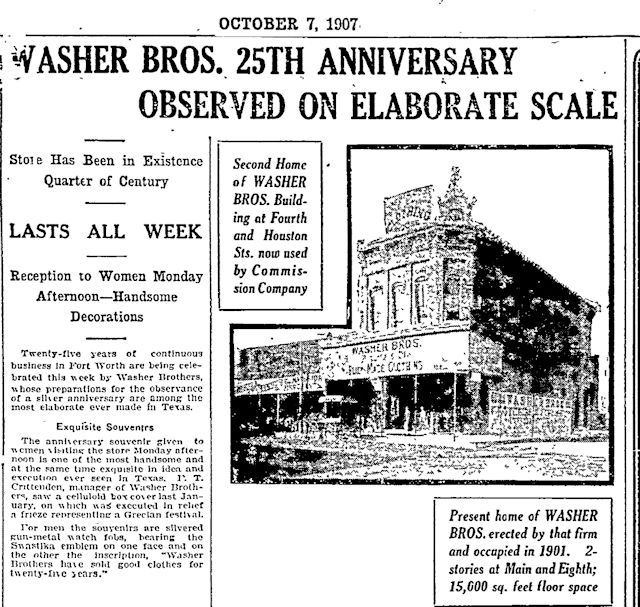

When Washer Bros. celebrated twenty-five years of business in 1907, male employees were given souvenir swastika emblem watch fobs.

When Washer Bros. celebrated twenty-five years of business in 1907, male employees were given souvenir swastika emblem watch fobs.

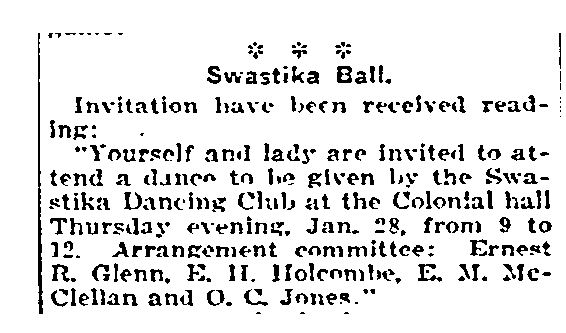

The popularity of the swastika symbol continued. In 1909 Fort Worth had a Swastika Dancing Club.

The popularity of the swastika symbol continued. In 1909 Fort Worth had a Swastika Dancing Club.

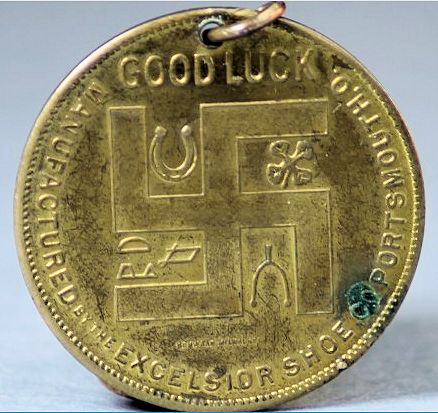

This token by the Excelsior Shoe Company is from 1910. The company sold a model of shoe named the “Boy Scout” to capitalize on organization of the Boy Scouts of America that year. Stripling’s Department Store sold Excelsior shoes.

This token by the Excelsior Shoe Company is from 1910. The company sold a model of shoe named the “Boy Scout” to capitalize on organization of the Boy Scouts of America that year. Stripling’s Department Store sold Excelsior shoes.

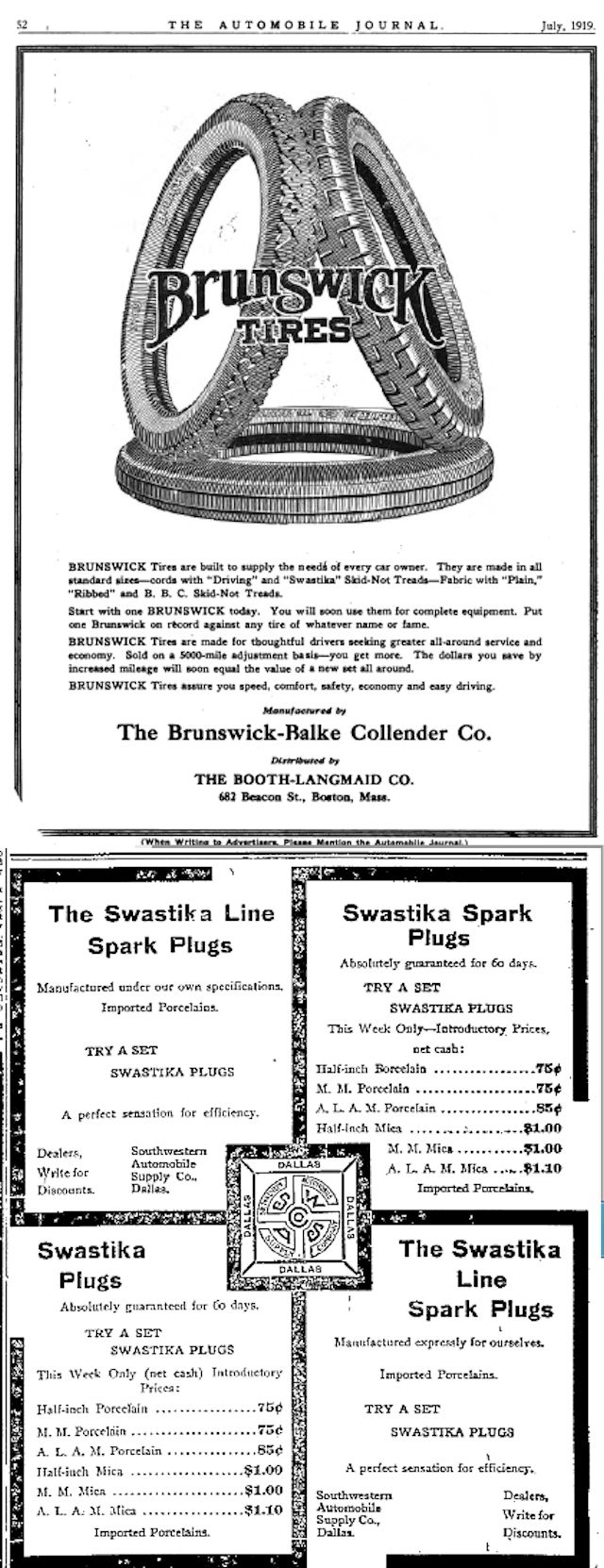

You could buy swastika-tread tires and Swastika brand spark plugs for your car.

You could buy swastika-tread tires and Swastika brand spark plugs for your car.

There were Lucky Swastika soap, Swastika Fuel Company, Swastika Ranch, and Swastika Oil Corporation.

There were Lucky Swastika soap, Swastika Fuel Company, Swastika Ranch, and Swastika Oil Corporation.

But the swastika’s positive image began to change in 1920. That’s when Adolf Hitler made the swastika the symbol of Germany’s Nazi Party as he began his rise to power.

(In 1925 Hitler would write in Mein Kampf: “. . . the swastika signified the mission allotted to us—the struggle for the victory of Aryan mankind and at the same time the triumph of the ideal of creative work which is in itself and always will be anti-Semitic.”)

Still, in 1924 the new insignia of the U.S. Army’s 45th Infantry Division—made up of National Guard units of the Southwest—featured a swastika, which is also a common Native American symbol.

And even in 1933 Dallas still had a Swastika Saddle Club.

And even in 1933 Dallas still had a Swastika Saddle Club.

But that year, Hitler became chancellor of Germany, and in March the swastika became the symbol of the German nation.

But that year, Hitler became chancellor of Germany, and in March the swastika became the symbol of the German nation.

Of course, the rest of the world didn’t turn on the swastika immediately. For example, in 1935 the masthead of the “Junior Edition” of The Handout student newspaper of Texas Wesleyan College featured swastikas.

Of course, the rest of the world didn’t turn on the swastika immediately. For example, in 1935 the masthead of the “Junior Edition” of The Handout student newspaper of Texas Wesleyan College featured swastikas.

By the late 1930s the swastika increasingly did take on a negative connotation to millions, and much of the world hasn’t seen the swastika through the same eyes since.

But in downtown Fort Worth two buildings remind us of a time before a good symbol went bad.

But in downtown Fort Worth two buildings remind us of a time before a good symbol went bad.

At our University, “someone” discovered that a Dorm built in 1926 contained … swastikas!

A “Campus Diversity Council” demanded its removal.

“The tiles show a mirror-image swastika called an aristika designed within Corbin Hall in the 1920s when swastikas were not yet adopted as a symbol by the Nazis, university officials said. The symbols were originally meant to celebrate Native American and east Asian culture.

“After months of calls for the tiles to be taken down amid the image’s negative connotation, the university’s Diversity Advisory Council voted Tuesday to recommended the tiles be removed, archived and replaced. The council will send the proposal to President Seth Bodnar.

“The student and faculty senates passed resolutions this fall for the tiles to be removed before the diversity council.” NBC News, December 11, 2019.

At the Native American museum in Gallup NM out by the Red Rock rodeo stadium, the main hall/entry’s floor has an inset mural naming the area tribes and prominent among the imagery is a rather large swastika. The building is definitely post WW2, and I respect the First Nations’ claiming ownership of *their* symbol and not bowing to western Europeans’ idea that a symbol can be permanently tainted in all contexts due to one conspicuously awful misuse.

Really fun article to read. I’d love to see you expand the article to Asia in the past and even Asia today, where it’s not at all uncommon to see swastikas, including on grave stones (e.g., in Vietnam). They never experienced Hitler so the symbol never was corrupted there.

Thank you. It is an eye-opening subject.

Has no one noticed that Hitler REVERSED the rotation direction of the swastika thus turning good luck into bad?

It is my understanding that before Nazi Germany adopted the right-hand swastika, some cultures used both the left-hand swastika and the right-hand swastika, with different meanings assigned to each.

When the arms point clockwise it signifies positive energy. Counterclockwise, negative energy. The swastika was used in both ways depending on the context.

My mother had a pair of pillowcases given to a great uncle by a Navajo woman with clockwise swastikas embroidered on them.

Now do the sig-heil salute. My understanding is that it dates back at least to the roman emperors and perhaps to the sermon on the mount. That would be an interesting exploration as well.

interesting article

check this out

https://thecjn.ca/news/swastika-trail-will-be-renamed-in-response-to-years-of-advocacy-in-ontarios-puslinch-township/

A great article. The swastika was also used by on the front leaf of Kipling’s and other books pre-WW2. I’ve seen several first additions with it.

Since the Plains tribes used it too, I wonder how much in Ft Worth and Dallas came from that. I’ll have to check the older building in my North Texas Home town too.

Thank you. It’s an eye-opening subject.

The Pan-Pacific Exposition before WW I has swastikas in many of the building exteriors.

Indeed. A Google search shows that Fort Worth certainly was not unique during those years.

I came across your interesting webpage while researching the Swastika.

We are a cultural group of Dharma followers ( Buddhists & Hindus, Jains & Sikhs) for whom the Swastika has a profoundly sacred and auspicious meaning.

We would like you to join our group to disseminate positive information about the Swastika as distinguished from the Nazi Hakenkreuz which has done so much to damage the millennia old positive history of the Swastika

Thank you. I was hoping someone would talk about that.

Back in the 1940’s in Dallas there was a brick home on Lindsley Ave, the street car line, which had a swastika brick pattern. This house was situated between Fitzhugh and Winslow and I suppose it is still there.

There was a house off of Meadowbrook in east Fort Worth that had swastikas worked into the brickwork. The owners painted the house to disguise them and later remodeled the exterior of the house.

How cool is that! Thank you Mike for the enlightenment and history lesson.

Thanks, Charles.

So, did Adolph subscribe to the Telegram before he joined up with the German Army in WW I? OTOH, the Aryan reference in “The Fair” may have partly reflected Fort Worth’s “southern side.”