“Line-Up for Yesterday”

H is for Hornsby;

When pitching to Rog,

The pitcher would pitch,

Then the pitcher would dodge.

—Ogden Nash in Sport magazine, 1949

Before he was a Hall of Famer, he was a North Sider.

And before he was a North Sider, he was a kid playing baseball on the sandlots of Austin and holding his own against older boys.

He later said: “I can’t remember anything that happened before I had a baseball in my hand.”

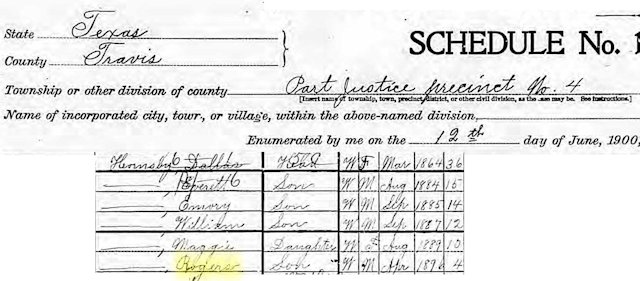

Rogers Hornsby was born in Runnels County in 1896 to Aaron Edward Hornsby and Mary Dallas Rogers.

Rogers Hornsby was born in Runnels County in 1896 to Aaron Edward Hornsby and Mary Dallas Rogers.

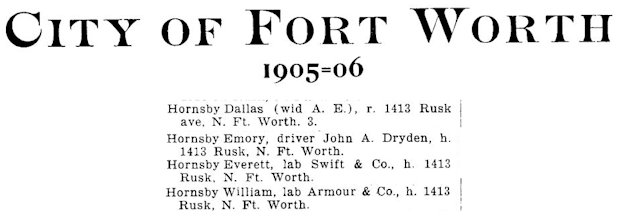

Father Hornsby died in 1898, and in 1903 Mary Hornsby moved her five children from Austin to Fort Worth so that she could take a job at the new packing plants. Her older sons Everett, Emory, and William also worked at the packing plants. The family rented a house near the plants.

Father Hornsby died in 1898, and in 1903 Mary Hornsby moved her five children from Austin to Fort Worth so that she could take a job at the new packing plants. Her older sons Everett, Emory, and William also worked at the packing plants. The family rented a house near the plants.

The Star-Telegram later wrote that by age nine Rogers Hornsby was the leader of a baseball team on the North Side. His mother made the team’s uniforms on her treadle sewing machine. The players traveled by streetcar all over town to play other teams and walked to games against Diamond Hill and Rosen Heights.

At age ten Rogers, too, took a job at the packing plants. He was a messenger boy at Swift.

The packing plants, as major employers, provided social and recreational outlets for their workers. Rogers earned ten cents a game as equipment manager for one of Swift’s adult baseball teams. Even at age ten he occasionally played as a substitute infielder.

He also played second base for a semipro team in Granbury, earning $2 a game plus room, board, and rail fare. Granbury manager H. L. Warlick recalled that he once complimented Hornsby on his fielding at second base.

Hornsby replied: “Yeah, and there are eight other positions I can play just as good.”

He also played baseball for North Side High School. But Hornsby was a poor student. In the tenth grade he dropped out to play amateur baseball.

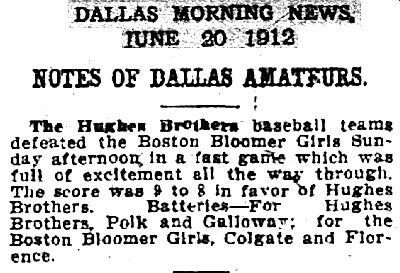

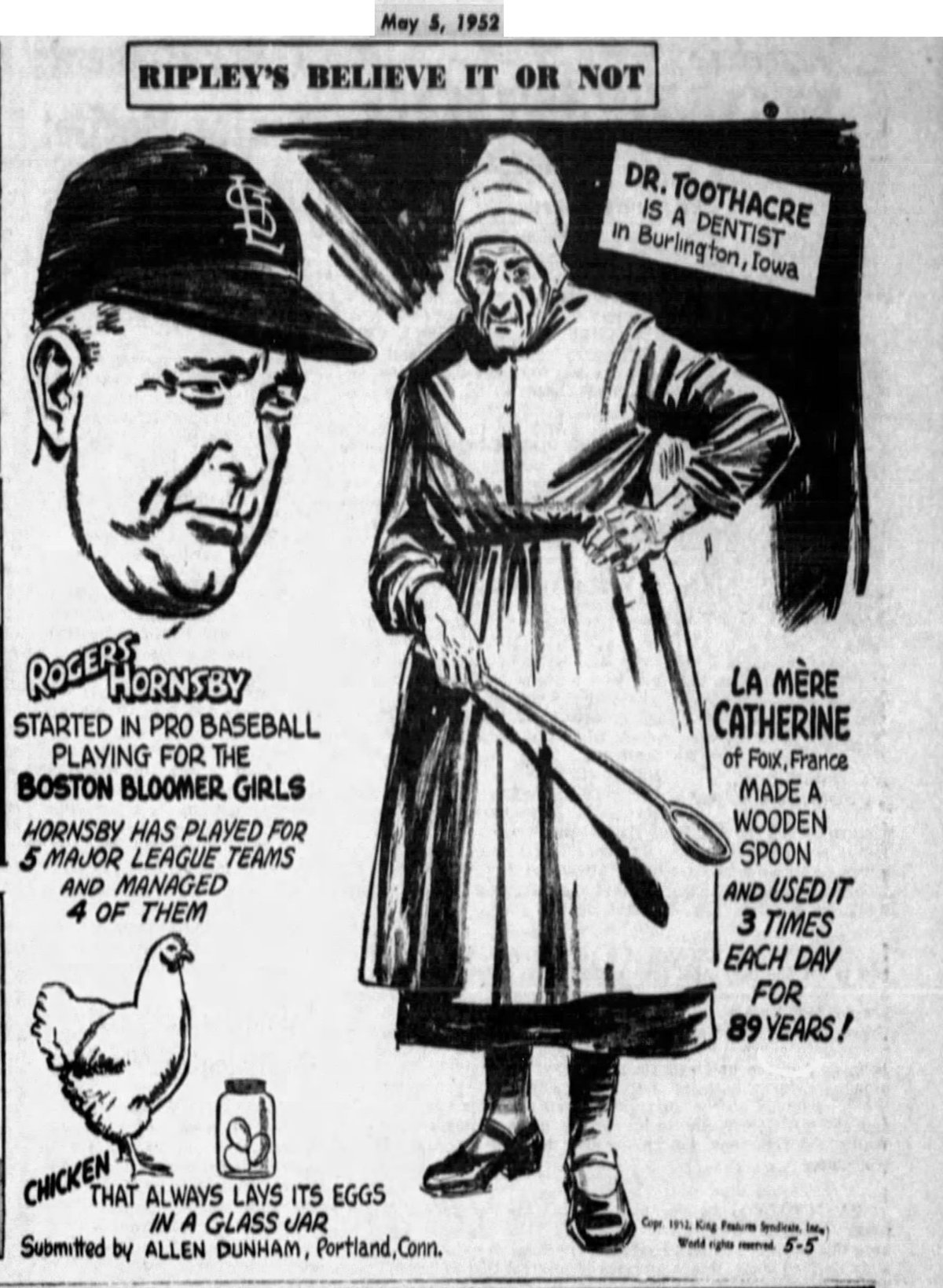

In 1912, the Star-Telegram later wrote, when promoter Logan J. Galbreath brought his traveling Boston Bloomer Girls team to Dallas, he was short two players, so he advertised, specifying that the players had to be under age eighteen. But he didn’t specify gender.

In 1912, the Star-Telegram later wrote, when promoter Logan J. Galbreath brought his traveling Boston Bloomer Girls team to Dallas, he was short two players, so he advertised, specifying that the players had to be under age eighteen. But he didn’t specify gender.

Hornsby rode the train to Dallas and was hired by Galbreath. Galbreath told Hornsby to wear women’s wigs and bloomers and “act like a girl” on the field. (Bloomers were pantaloons named for suffragette Amelia Jenks Bloomer, who advocated them as women’s wear because bloomers were less restrictive than corsets and dresses.)

Hornsby rode the train to Dallas and was hired by Galbreath. Galbreath told Hornsby to wear women’s wigs and bloomers and “act like a girl” on the field. (Bloomers were pantaloons named for suffragette Amelia Jenks Bloomer, who advocated them as women’s wear because bloomers were less restrictive than corsets and dresses.)

In 1914, at age eighteen, Rogers earned a place on the Denison Champions and Hugo Scouts of the class D Texas-Oklahoma League. In 1915 he started the season with the Denison Railroaders of the class D Western Association.

But in September the St. Louis Cardinals of the National League discovered him and bought his contract for $600 ($16,000 today).

But in September the St. Louis Cardinals of the National League discovered him and bought his contract for $600 ($16,000 today).

Rogers Hornsby, nineteen years old, had just tied his cleats to a shooting star.

But standing 5 feet 11 and weighing only 135 pounds in 1915, Rogers Hornsby was a skinny kid, a walking fungo bat.

After an unremarkable first season (only eighteen games played) with the Cardinals in 1915, Hornsby spent the winter working—and eating—on his uncle’s farm. He gained thirty-five pounds, much of it muscle. Fungo bat no more.

After an unremarkable first season (only eighteen games played) with the Cardinals in 1915, Hornsby spent the winter working—and eating—on his uncle’s farm. He gained thirty-five pounds, much of it muscle. Fungo bat no more.

Thereafter through 1922 Hornsby would spend his off-seasons in Fort Worth. (In the clip, the Cardinals were sometimes called the “Nationals” to distinguish them from the St. Louis Browns of the American League.) (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In his first full season with the Cardinals in 1916 at age twenty Hornsby hit .313—a great average for a veteran, a phenomenal average for a rookie.

Pshaw, Maw, ’tain’t nothin’. Eight years later Rogers Hornsby would eclipse that .313 average—by 111 points!

In fact, Rogers Hornsby would become baseball royalty.

He would even have a royal title.

Babe Ruth was called the “Sultan of Swat” by at least 1920.

Babe Ruth was called the “Sultan of Swat” by at least 1920.

Similarly, by 1925 Hornsby’s Christian name “Rogers” easily became “Rajah,” and thus Hornsby became the “Rajah of Swat,” soon shortened to just “the Raj.”

Similarly, by 1925 Hornsby’s Christian name “Rogers” easily became “Rajah,” and thus Hornsby became the “Rajah of Swat,” soon shortened to just “the Raj.”

Yes, the Raj was baseball royalty—but royalty in the rough.

Although Hornsby seldom argued with umpires, he argued with just about everyone else. He was gruff, sharp-tongued, overbearing, devoid of tact.

Sportswriter Lee Allen wrote of Hornsby: “He was frank to the point of being cruel and as subtle as a belch.”

Baseball historian Bill James: “If a contest is ever held to determine the biggest horse’s ass in baseball history, there are really only seven men, four of them players, who could hope to compete at that level. The four players are Hornsby, Ty Cobb, Dick Allen, and Hal Chase. I think I might choose Hornsby.”

Journalist Westbrook Pegler: “He has go-to-hell eyes.”

Sports Illustrated writer Ron Fimrite: “Hornsby was . . . cold-blooded, pigheaded, humorless, and obsessive, a curmudgeon who regarded as utterly worthless anything that did not involve throwing, catching, or hitting a baseball.”

Hornsby had little patience with players less talented than he. And that was most players.

His three marriages were stormy.

He also was man of precise regimen.

His diet was mostly red meat and milk.

He neither smoked nor drank and had but one weakness: ice cream.

He avoided watching movies and reading fine print to preserve his eyesight.

He didn’t play cards. Didn’t play golf. (“I don’t want to play golf. When I hit a ball, I want someone else to go chase it.”)

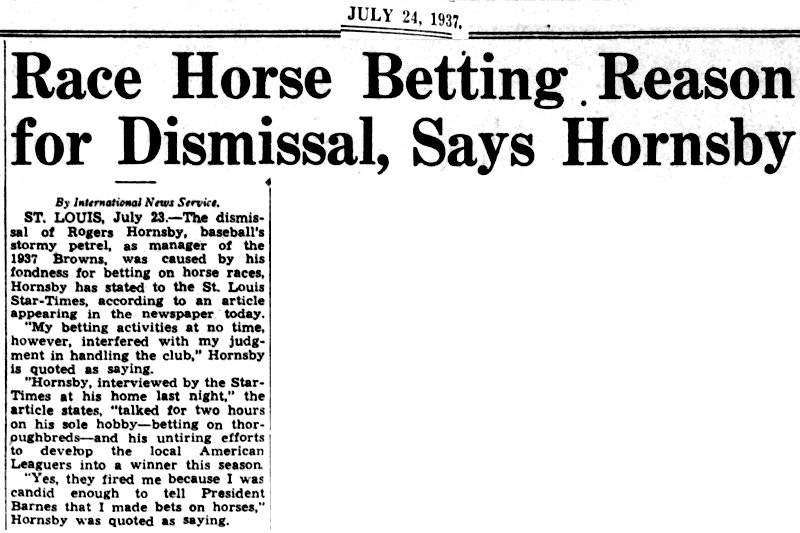

He had only two interests: baseball (“People ask me what I do in winter when there’s no baseball. I’ll tell you what I do. I stare out the window and wait for spring.”) and gambling on horse racing. He bet often. And lost. Betting got him into trouble with the league office (“It’s my money, so what’s it their business what I do with it?”), bookies, and the IRS.

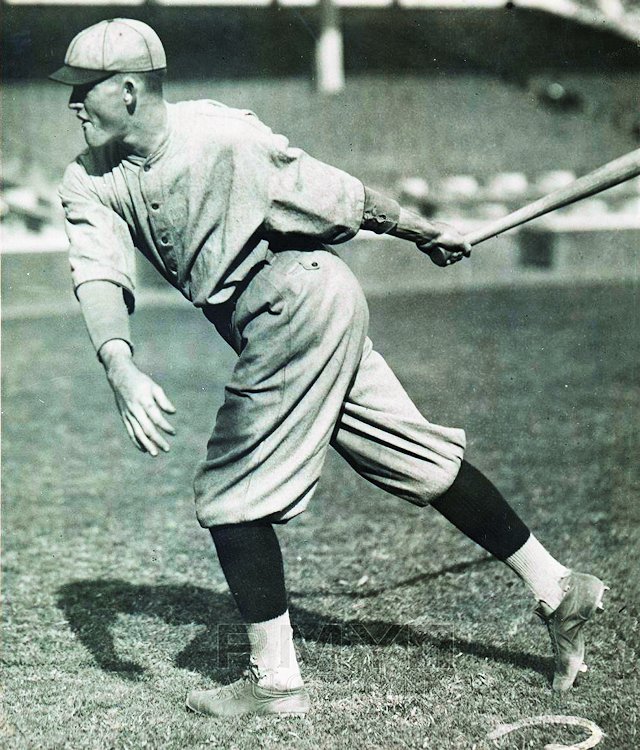

Hornsby in 1920. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Hornsby in 1920. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

The Raj played twenty-four years in the major leagues. And personality aside, he is generally regarded as the greatest right-handed hitter of all time (Remember: Ty Cobb, Ted Williams, Lou Gehrig, Babe Ruth, for example, were southpaws).

A recitation of the Raj’s offensive numbers reads like a baseball statistician’s fever dream:

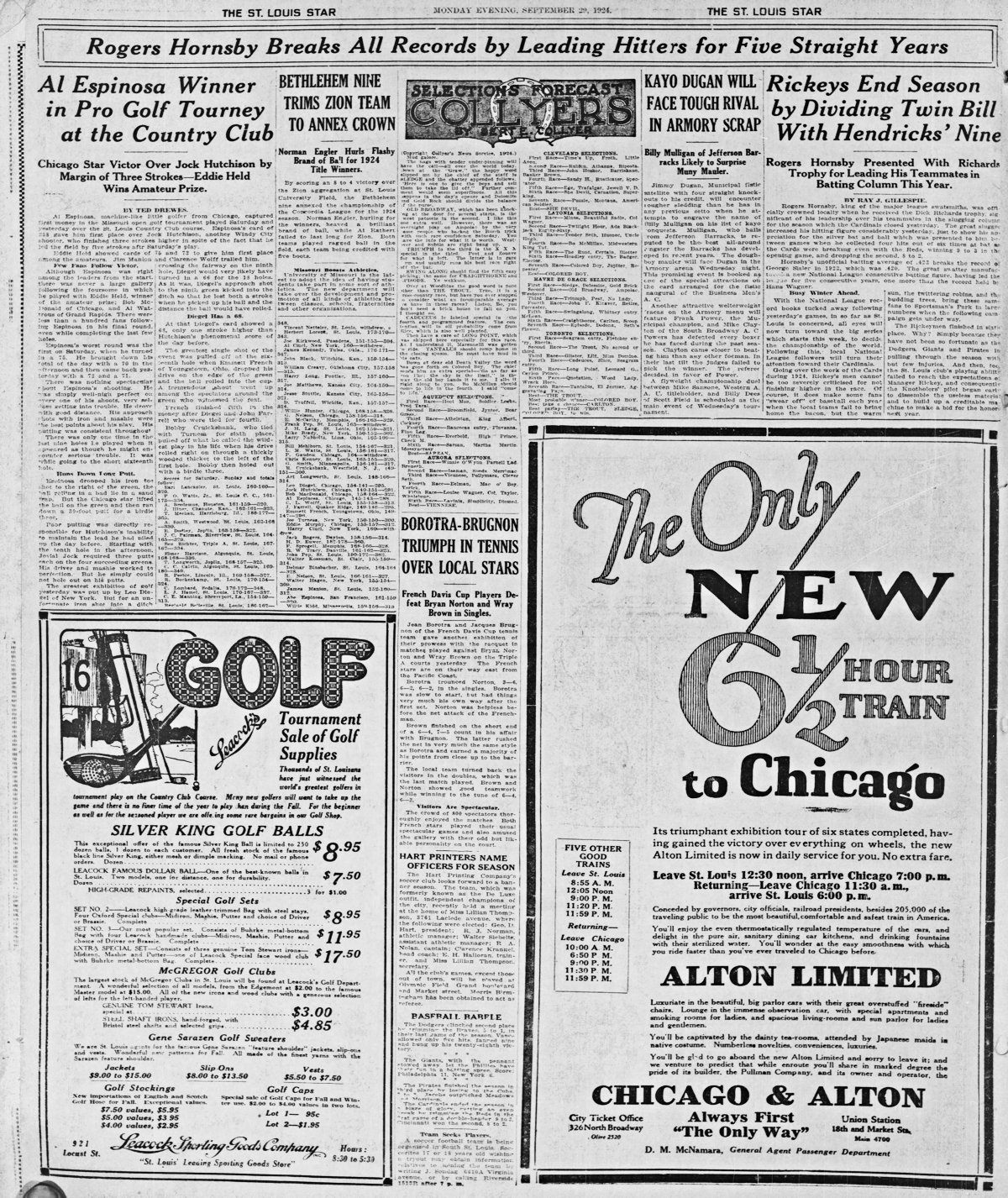

He won two Triple Crowns (leading the league in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in over the season), two MVP awards, seven batting titles, four RBI titles, two home run titles, led the league in hits four times, in runs five times, in slugging percentage (the total number of bases a player records per at-bat) nine times.

Not to mention, he had seven two hundred-plus-hit seasons.

The year 1920 was his breakout season. He hit .370. And he was just getting started.

Beginning in 1920 Hornsby won six straight National League batting championships. For the next five seasons, 1921 through 1925, he hit .397, .401, .384, .424 (the best single season batting average in modern baseball history), and .403, perhaps the most dominating five-year stretch in baseball history. His batting average over those five years was a stratospheric (and statospheric) .402.

Beginning in 1920 Hornsby won six straight National League batting championships. For the next five seasons, 1921 through 1925, he hit .397, .401, .384, .424 (the best single season batting average in modern baseball history), and .403, perhaps the most dominating five-year stretch in baseball history. His batting average over those five years was a stratospheric (and statospheric) .402.

Arthur Daley of the New York Times called that “the most unbelievable period of batting greatness in baseball history.”

Perhaps Hornsby’s most remarkable season was 1922, when he won the Triple Crown and dominated the league in seven major offensive categories, among them:

His .401 batting average was almost fifty points higher than that of the runner-up.

His forty-two home runs were sixteen more than the runner-up.

His 152 RBIs, twenty more.

His 250 hits, thirty-five more.

His 450 total bases, 136 more.

His .722 slugging percentage, 150 points more.

Since 1900 major league players have hit .400 or better only thirteen times. Rogers Hornsby accounted for three of the thirteen.

His .358 lifetime batting average is second only to Ty Cobb’s .367.

He also was the first National Leaguer to reach three hundred home runs (301—33 of them inside the park). But predictably the .400 hitter was more interested in average than distance:

“The home run became glorified with Babe Ruth,” Hornsby recalled. “Starting with him, batters have been thinking in terms of how far they could hit the ball, not how often.”

The careers of Ruth and Hornsby ran in close parallel. Ruth, born in 1895, reached the majors in 1914 and retired in 1935. Hornsby, born in 1896, reached the majors in 1915 and retired in 1937. Hornsby at his peak was the highest-paid player in the National League, just as Ruth was in the American League.

Rogers Hornsby was in the National League what Babe Ruth was in the American League: a superstar before the word existed.

After reading all that, consider this: Rogers Hornsby never played in an All-Star Game. By the time the first All-Star Game was played in 1933 Hornsby’s career was in decline.

What others said about him:

Hall of Fame pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander: “Hornsby is the greatest hitter I’ve ever had to face. . . . Personally, I don’t think a more skillful man ever stepped up to the plate.”

Hall of Fame outfielder Ted Williams: “I’ve always felt Rogers Hornsby was the greatest hitter for average and power in the history of baseball.”

Hall of Fame infielder Frankie Frisch: “He’s the only guy I know who could hit .350 in the dark.”

Sportswriter Joe Williams: “If consistency is a jewel, then Mr. Hornsby is a whole rope of pearls.”

From 1925 through 1937 Hornsby played both infield and outfield and managed the teams he played on (St. Louis Cardinals, New York Giants, Boston Braves, Chicago Cubs, St. Louis Browns).

His managerial career was far less successful than his playing career. His winning percentage was only .463 (phenomenal for a batter; lackluster for a manager).

The highlight of his career as a manager came in 1926 when he took his Cardinals to their first National League pennant and then beat Babe Ruth and the Yankees in the World Series. Hornsby played all seven games at second base.

But soon after winning the World Series in 1926 Hornsby was traded to the New York Giants. The Cardinals wanted to get rid of the “friction” that Hornsby created, and the Giants wanted Hornsby as a counter draw to Babe Ruth in New York City.

But soon after winning the World Series in 1926 Hornsby was traded to the New York Giants. The Cardinals wanted to get rid of the “friction” that Hornsby created, and the Giants wanted Hornsby as a counter draw to Babe Ruth in New York City.

But the Giants kept Hornsby just one season.

Rogers Hornsby had played his first twelve years with one team. Over the next twelve years he would play with six teams.

Other players did not like him because of his authoritarian leadership style. Club owners did not like him because he bristled at any criticism of his management decisions.

“If you don’t like the way I am managing your club,” he would say, “pay me off and get somebody else.”

They did.

Hornsby in 1928. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Hornsby in 1928. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Finally, in 1937 the St. Louis Browns released Hornsby because of his gambling. He told the Star-Telegram:

Finally, in 1937 the St. Louis Browns released Hornsby because of his gambling. He told the Star-Telegram:

“Yes, they fired me because I was candid enough to tell [club] President Barnes that I made bets on horses.”

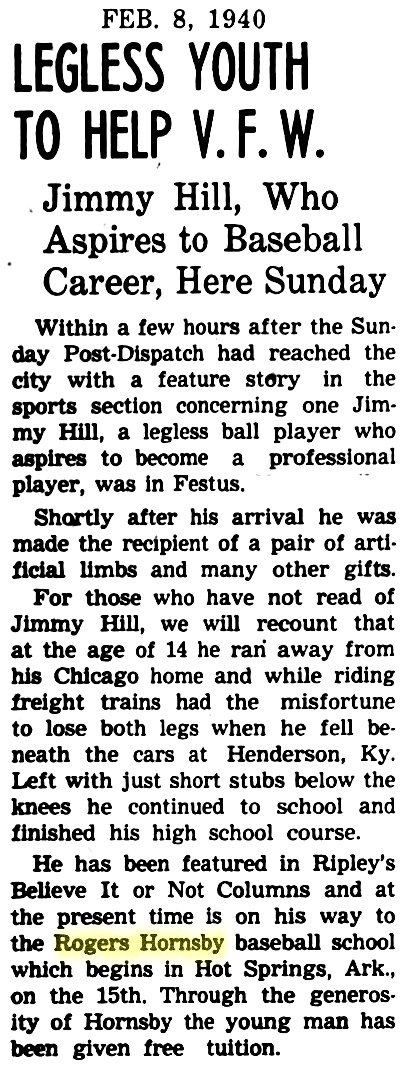

With that, Roger Hornsby’s major league career was over. Hornsby then became involved in youth baseball. He directed a Chicago Daily News youth baseball program. He operated his own baseball school in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Rogers Hornsby, it was generally agreed, was not a cuddly person. However, when a man with no legs but a big heart came along, Hornsby showed that he, too, could have a big heart.

Rogers Hornsby, it was generally agreed, was not a cuddly person. However, when a man with no legs but a big heart came along, Hornsby showed that he, too, could have a big heart.

Jimmy Hill, twenty-five, had lost his feet in a railroad accident at age fourteen. Undaunted, he strapped on prostheses made from automobile tires and played shortstop for semipro teams. Rogers Hornsby gave him full tuition to his baseball school.

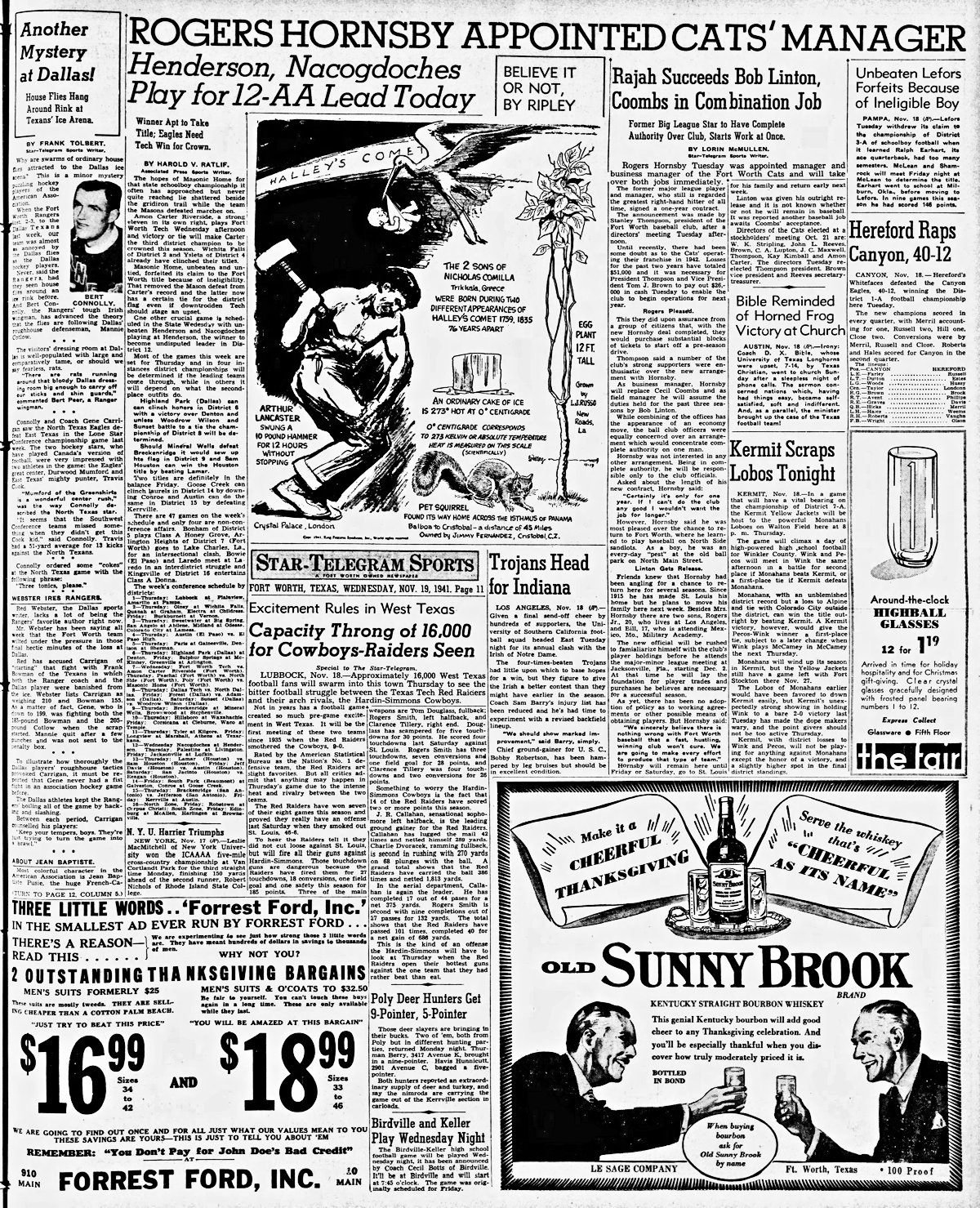

In November 1941, three weeks before Pearl Harbor, Hornsby was named manager of the Fort Worth Cats.

In November 1941, three weeks before Pearl Harbor, Hornsby was named manager of the Fort Worth Cats.

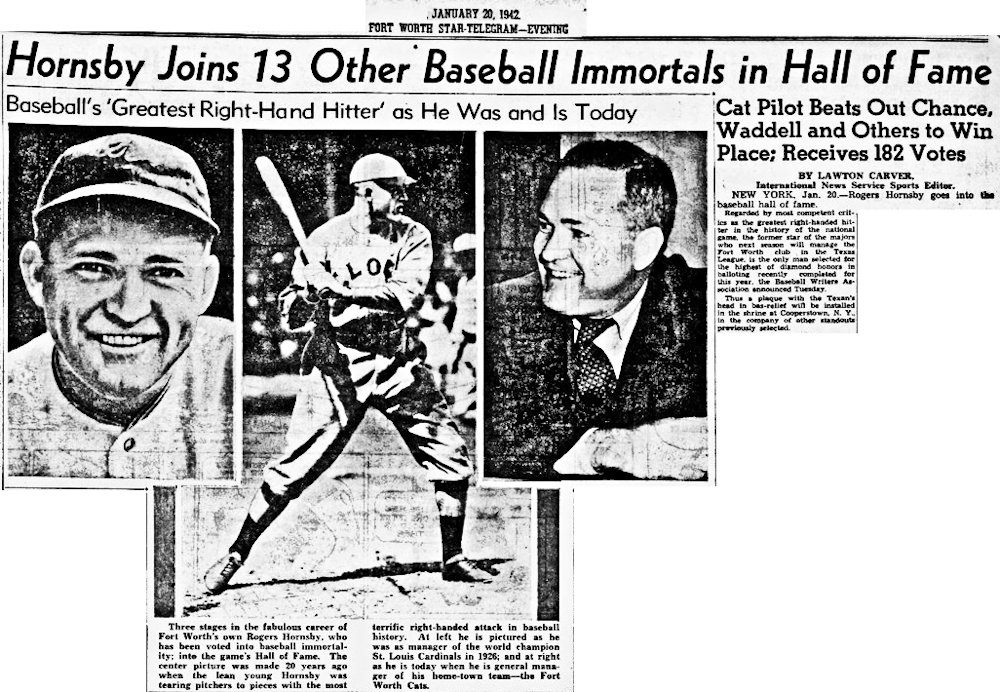

Hornsby was manager of the Cats in 1942 when he was elected to the Hall of Fame. When he heard the news, he ordered a double portion of ice cream. Because of the war, the Texas League did not play again until 1946. So, Hornsby went to Mexico to manage the Vera Cruz Blues. He lasted nine days.

Hornsby was manager of the Cats in 1942 when he was elected to the Hall of Fame. When he heard the news, he ordered a double portion of ice cream. Because of the war, the Texas League did not play again until 1946. So, Hornsby went to Mexico to manage the Vera Cruz Blues. He lasted nine days.

Hornsby died in Chicago in 1963 at age sixty-six.

Hornsby died in Chicago in 1963 at age sixty-six.

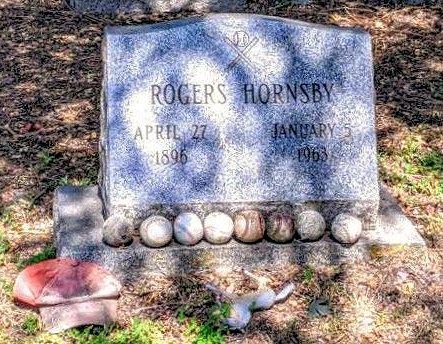

He is buried in the family cemetery in Hornsby Bend in Travis County. His great-grandfather Reuben Hornsby, a surveyor for Stephen F. Austin, founded Hornsby Bend on the Colorado River in 1832.

He is buried in the family cemetery in Hornsby Bend in Travis County. His great-grandfather Reuben Hornsby, a surveyor for Stephen F. Austin, founded Hornsby Bend on the Colorado River in 1832.

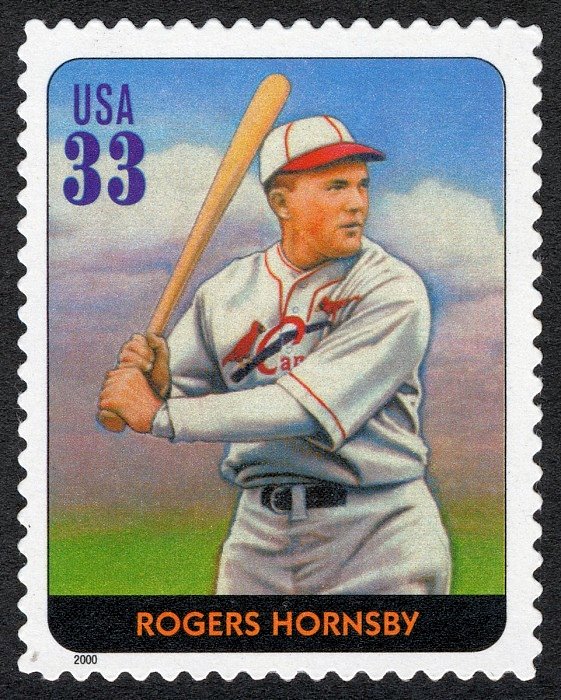

Rogers Hornsby, the kid from the North Side who became America’s Rajah of Swat, was honored with a postage stamp in 2000.

Rogers Hornsby, the kid from the North Side who became America’s Rajah of Swat, was honored with a postage stamp in 2000.