The Star-Telegram described her as “small, wizened, gray haired, and sunken eyed.”

Her children and husband described her as a loving mother who fought tenaciously to keep her family away from the temptations of crime.

But law enforcement officials painted a far darker portrait: The FBI called Lucy Beland the leader of “the nation’s leading dope runners.” Those dope runners were Lucy Beland’s three daughters and two sons. The Federal Narcotics Bureau called Ma Beland and her five children “notorious.”

In the first half of the twentieth century Ma Beland was the godmother of a Cowtown mini-Mafia.

Law enforcement officials said Ma Beland made prostitutes and shoplifters of her daughters. When her children—daughters and sons—became drug addicts, police said, Ma Beland “commercialized” their addiction and supervised them as they sold morphine, heroin, and cocaine on a large scale. One daughter died of an overdose. Another daughter committed suicide. Two sons were incarcerated so often that they beat a virtual Leavenworth Trail between Fort Worth and the federal penitentiary in Kansas.

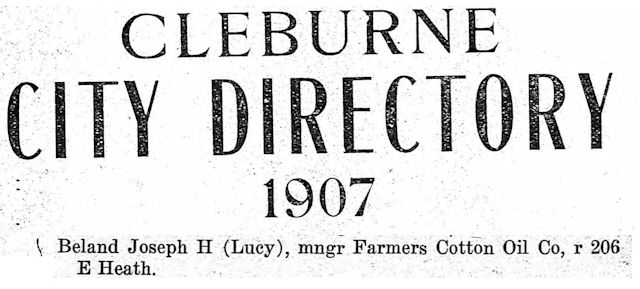

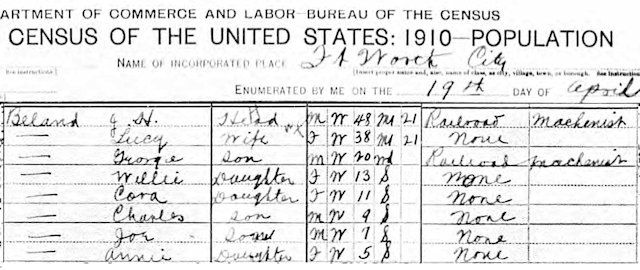

Lucille Pounds was born in Georgia in 1870. About 1891 she married Joseph Henry Beland, also of Georgia. After son George was born in 1892 the Belands moved to Johnson County, where father Joe managed a cotton oil mill.

Lucille Pounds was born in Georgia in 1870. About 1891 she married Joseph Henry Beland, also of Georgia. After son George was born in 1892 the Belands moved to Johnson County, where father Joe managed a cotton oil mill.

About 1908 the Belands, then with six children, moved to Fort Worth. Father Joe and oldest son George worked for railroads.

About 1908 the Belands, then with six children, moved to Fort Worth. Father Joe and oldest son George worked for railroads.

Ma Beland chose other careers for her other five children.

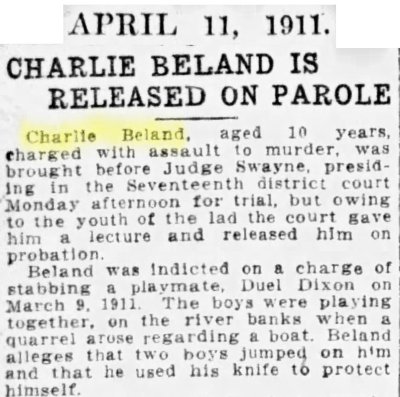

In 1911 two of Ma Beland’s children came to the attention of police. Charles, age ten, stabbed another boy during an argument and was charged with assault to murder. Judge James W. Swayne gave the boy a lecture and released him on probation.

In 1911 two of Ma Beland’s children came to the attention of police. Charles, age ten, stabbed another boy during an argument and was charged with assault to murder. Judge James W. Swayne gave the boy a lecture and released him on probation.

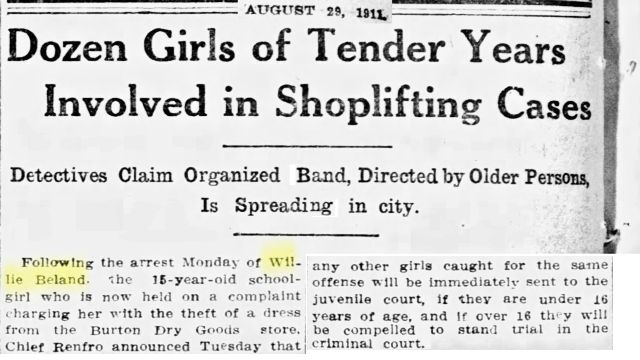

Also in 1911 daughter Willie, age fifteen, was arrested for shoplifting. Police suspected that Willie was a member of a “ring” of girls aged ten to fifteen. The girls refused to name their leader, but police said the girls’ precocious skills at shoplifting pointed to an adult ringleader.

Also in 1911 daughter Willie, age fifteen, was arrested for shoplifting. Police suspected that Willie was a member of a “ring” of girls aged ten to fifteen. The girls refused to name their leader, but police said the girls’ precocious skills at shoplifting pointed to an adult ringleader.

Police would determine that Ma Beland conducted a shoplifting school—at least for her three daughters. Her sons Joe Jr. and Charles acted as store detectives as the daughters learned to avoid detection.

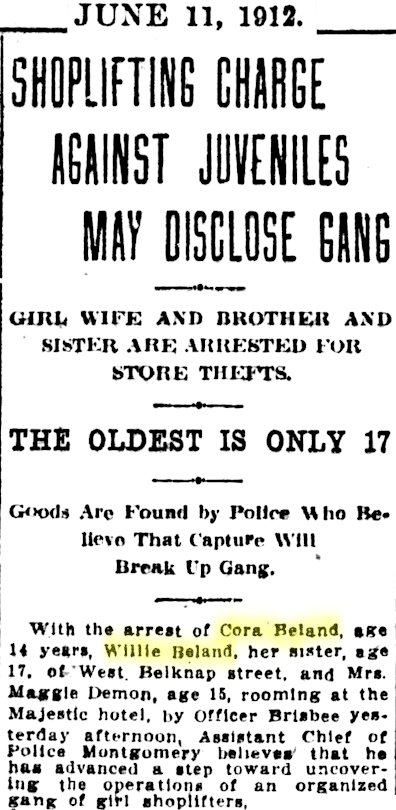

In 1912 Willie was again arrested for shoplifting, as was sister Cora, age fourteen. With a third girl, the sisters were accused of stealing from Burton’s and Stripling’s department stores as part of “an organized gang of girl shoplifters, whose pretty faces and artless, innocent airs have been successful in blinding the clerks in half a dozen big department stores here” and whose members “have shown consummate cunning in covering up their tracks.”

In 1912 Willie was again arrested for shoplifting, as was sister Cora, age fourteen. With a third girl, the sisters were accused of stealing from Burton’s and Stripling’s department stores as part of “an organized gang of girl shoplifters, whose pretty faces and artless, innocent airs have been successful in blinding the clerks in half a dozen big department stores here” and whose members “have shown consummate cunning in covering up their tracks.”

The Star-Telegram wrote: “When the [three] girls were arrested at Burton’s . . . goods valued at $30 [$800 today] were found concealed upon two of them. Employees of the store state that one of the girls engaged the clerk in conversation, artlessly diverting his attention from the other two,” each of whom “took one garment from the counters, one securing a silk dress which she secreted with remarkable rapidity, and the other obtaining a woman’s handsome undergarment.”

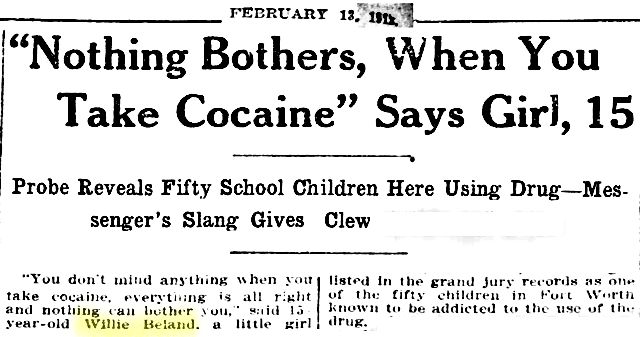

That same year Willie was arrested for cocaine possession. Law enforcement officials estimated that “at least fifty children of the city, boys and girls ranging in age from ten to sixteen years, are habitual users of cocaine and morphine.”

That same year Willie was arrested for cocaine possession. Law enforcement officials estimated that “at least fifty children of the city, boys and girls ranging in age from ten to sixteen years, are habitual users of cocaine and morphine.”

Among the young cocaine users were messenger boys, who referred to themselves as “snow heads.”

Willie Beland told a Star-Telegram reporter: “Just take a tiny pinch of the powder and snuff it up your nose and directly you will feel so good that you just don’t care what happens to you or what you do.”

Willie said she was first given cocaine by a boy at a restaurant.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “She said that the boy told her where she could get the cocaine and that she liked it.”

Afterward “Mama and Papa gave me money to go to the picture shows and to the theater, and I took it and bought cocaine with it. I used other money Mama gave me to buy groceries with and told her when I got home that I had lost the money.”

Willie said she used cocaine for months before her parents found out. Willie did not implicate her mother or any other member of her family in her drug use.

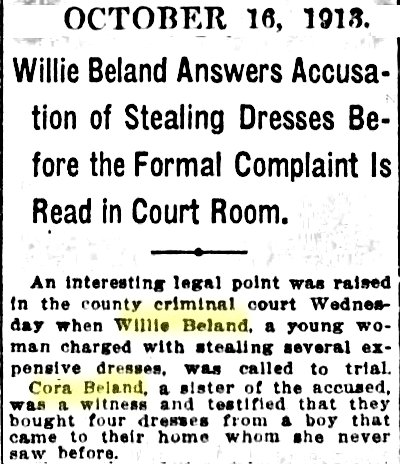

In 1913 Willie was arrested for stealing dresses. Her sister Cora testified that she and Willie had bought the dresses from a boy who came to their home.

In 1913 Willie was arrested for stealing dresses. Her sister Cora testified that she and Willie had bought the dresses from a boy who came to their home.

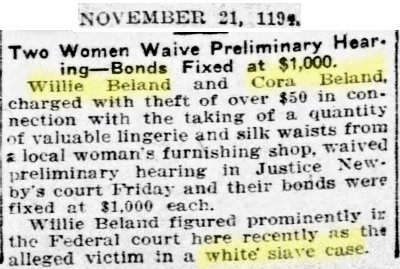

A year later Willie and Cora were charged with theft of clothing. Note the reference to Willie as the “alleged victim in a white slave case” (prostitution).

A year later Willie and Cora were charged with theft of clothing. Note the reference to Willie as the “alleged victim in a white slave case” (prostitution).

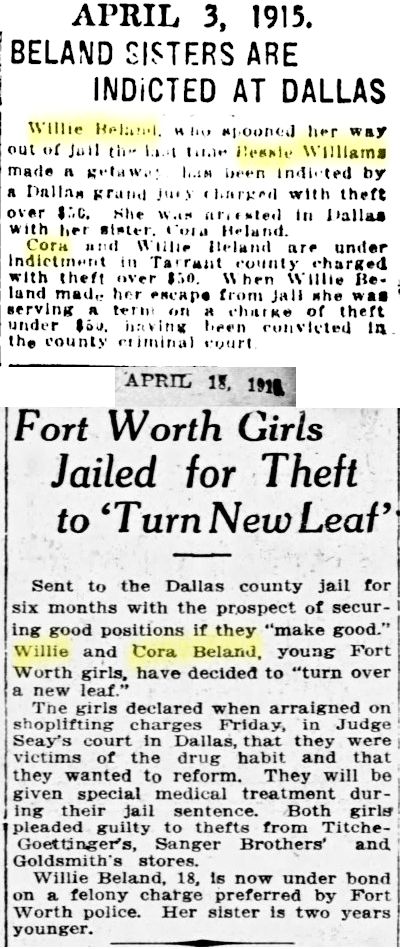

In 1915 Willie and Cora were indicted for theft in Dallas. Note that Willie had spooned her way out of the Tarrant County jail with fellow inmate Bessie Williams, the Houdini of the hoosegow.

In 1915 Willie and Cora were indicted for theft in Dallas. Note that Willie had spooned her way out of the Tarrant County jail with fellow inmate Bessie Williams, the Houdini of the hoosegow.

Two weeks after being indicted in Dallas, Cora and Willie vowed to turn over a new leaf, kick their drug habit, and go straight.

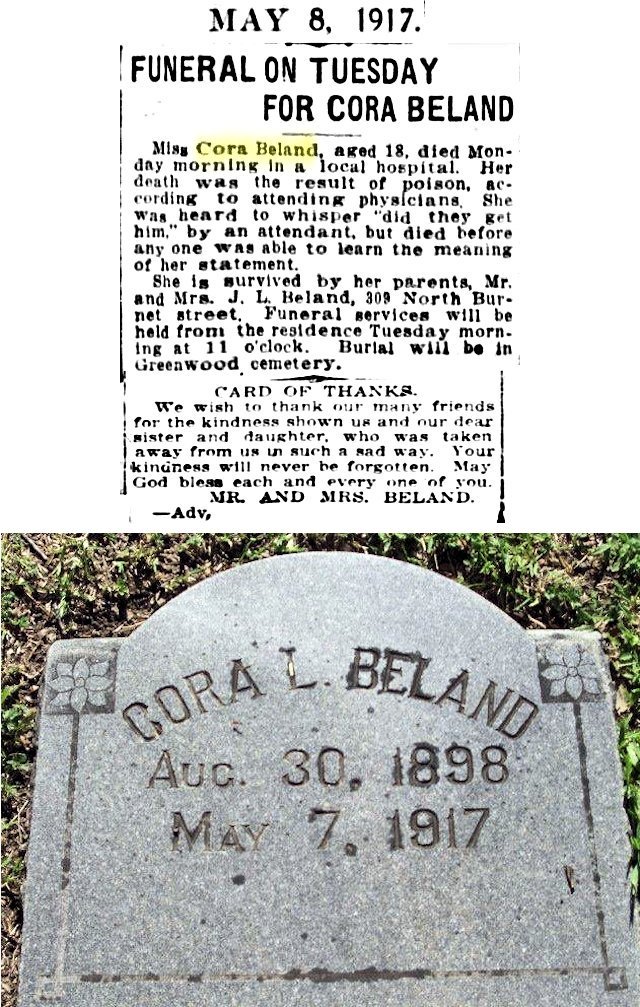

Two years later Cora was dead. Police said she had overdosed in her jail cell after family members smuggled morphine to her. Cora was buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Two years later Cora was dead. Police said she had overdosed in her jail cell after family members smuggled morphine to her. Cora was buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

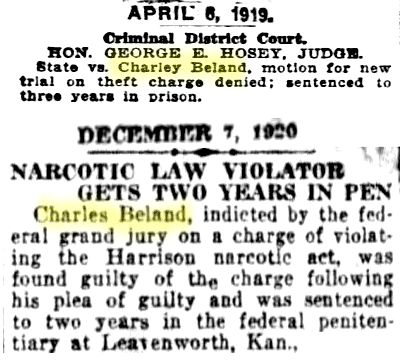

In 1918 Charles, age eighteen, received a five-year suspended sentence after pleading guilty to theft. The next year he received a three-year suspended sentence for a narcotics violation. The next year he received a two-year sentence in Leavenworth federal penitentiary for another narcotics violation. He ended up facing five years because the 1920 conviction revoked the suspension of the 1919 conviction.

In 1918 Charles, age eighteen, received a five-year suspended sentence after pleading guilty to theft. The next year he received a three-year suspended sentence for a narcotics violation. The next year he received a two-year sentence in Leavenworth federal penitentiary for another narcotics violation. He ended up facing five years because the 1920 conviction revoked the suspension of the 1919 conviction.

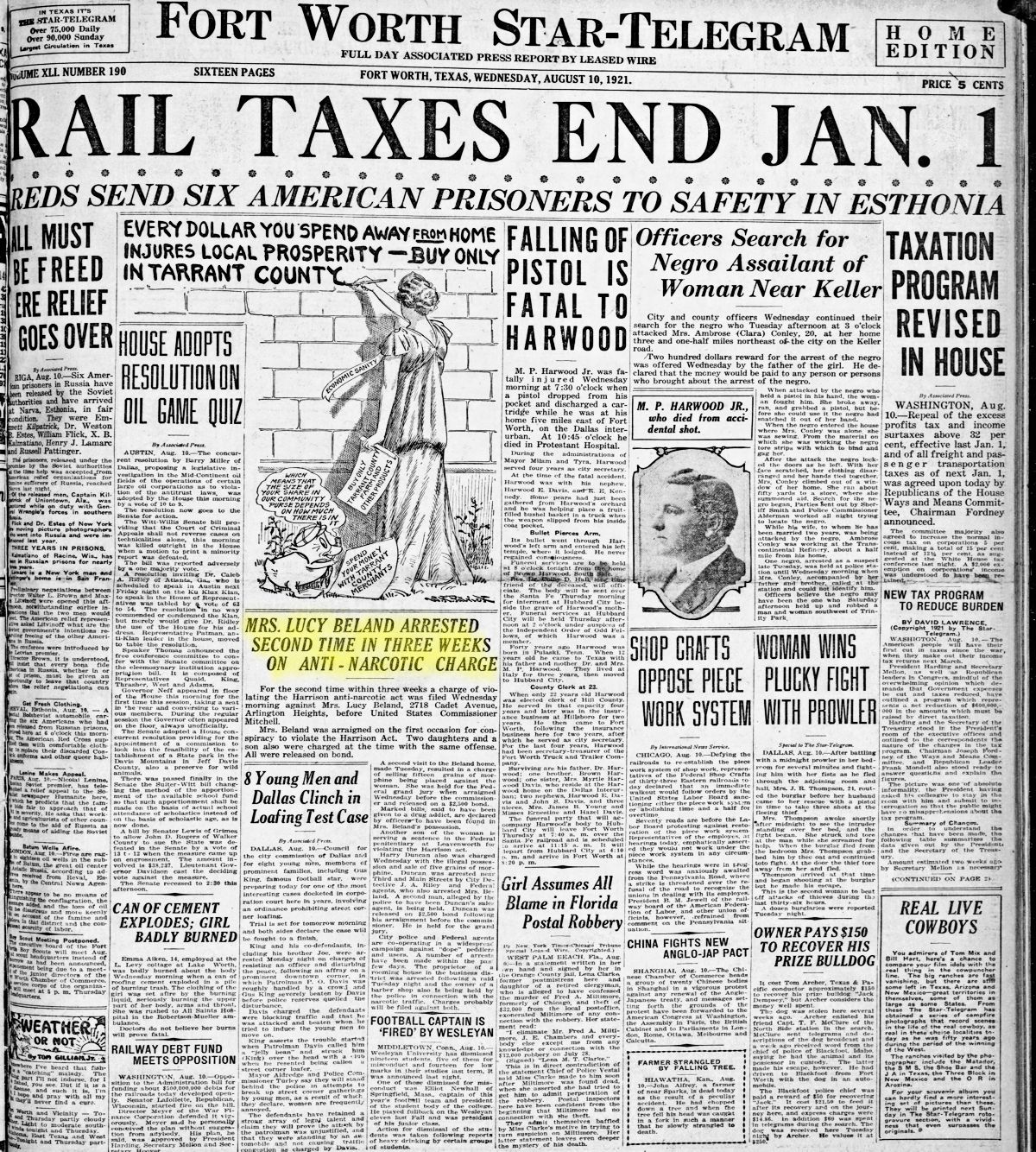

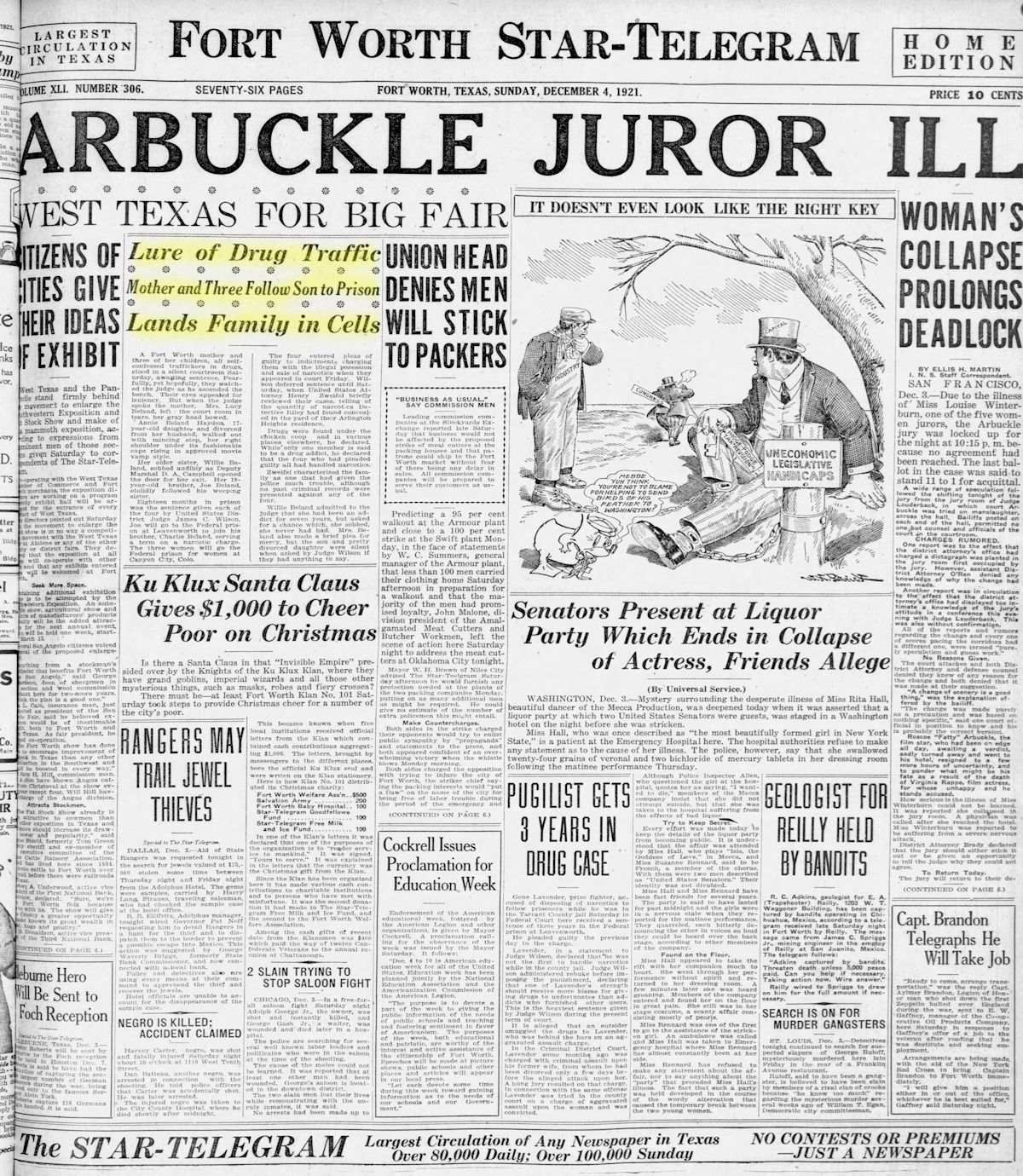

For Ma Beland and her children, the snow hit the fan in 1921. Ma Beland and her gang made the big time: the front page of the Star-Telegram and federal prison.

For Ma Beland and her children, the snow hit the fan in 1921. Ma Beland and her gang made the big time: the front page of the Star-Telegram and federal prison.

Twice in three weeks police and federal investigators raided Ma Beland’s house in Arlington Heights and arrested her and children Willie, Joe Jr., and last-born Annice for narcotics trafficking. (Charles was still in Leavenworth.)

Investigators found narcotics hidden at various places around the Beland property, including four ounces of morphine in a baking powder can tucked under a sitting hen. Investigators also recovered marked money that an addict had paid to Ma Beland in a narcotics transaction.

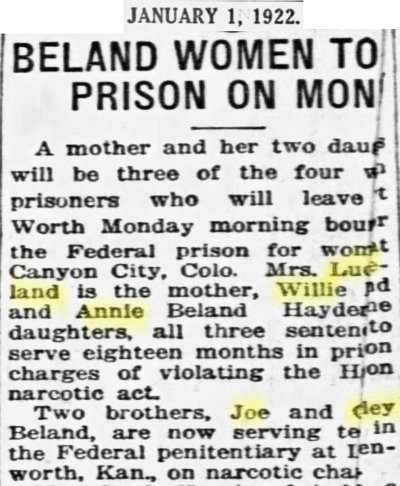

In December the Star-Telegram described Ma Beland and Joe Jr., Willie, and Annice as “self-confessed traffickers in drugs.” The women had been sentenced to eighteen months at a women’s federal prison in Colorado. Joe Jr. also was sentenced to eighteen months and would ride the Leavenworth Trail north to join brother Charles.

In December the Star-Telegram described Ma Beland and Joe Jr., Willie, and Annice as “self-confessed traffickers in drugs.” The women had been sentenced to eighteen months at a women’s federal prison in Colorado. Joe Jr. also was sentenced to eighteen months and would ride the Leavenworth Trail north to join brother Charles.

As the four Belands prepared to go to prison, daughter Willie, then twenty-four, admitted to being a morphine addict for seven years.

She told the Star-Telegram: “My sister, Cora, and I were little girls when we started to the Second Ward School here in Fort Worth. I was about twelve, I guess, when some of the children in the school gave me some morphine. We thought it was fun, so we kept on slipping out and getting it. Half the children in school ate it. You could buy it then for twenty-five cents for a big bottle. . . . Anyway, Mama, [sister] Annice, brother [Joe Jr.], and I have been arrested, and here we are. We’ve got to go to prison.”

The Star-Telegram wrote: “Through the years, as the mother brought her six babies into the world she watched nearly all of them, one after the other, struggle, bow down, and fall helpless in the grip of the morphine vice.

“Friends who know Mrs. Beland best are staunch in their denial that the mother uses the drug. The daughters say that their mother kept it for her family victims but that she did not use it.”

Even though Ma Beland had confessed in court to illegal possession and sale of narcotics, she continued to profess her innocence to the Star-Telegram: “The woman herself—small, wizened, gray haired, and sunken eyed—speaking in the thin voice of resentful despair, pleaded her own innocence.

“‘We lived in a small town, Cleburne, when the babies were little. I’m ashamed to confess my ignorance, but I never heard of such a thing as morphine . . .’”

As the year 1922 began, Ma Beland, age fifty, and four of her five children were in prison or in jail awaiting transfer to prison for narcotics violations.

As the year 1922 began, Ma Beland, age fifty, and four of her five children were in prison or in jail awaiting transfer to prison for narcotics violations.

With Ma Beland and her gang behind bars, so ended the reign of the godmother of Cowtown’s mini-Mafia, right?

What do you think?

(Thanks to Justin Tate and Donna Humphrey Donnell for their help.)