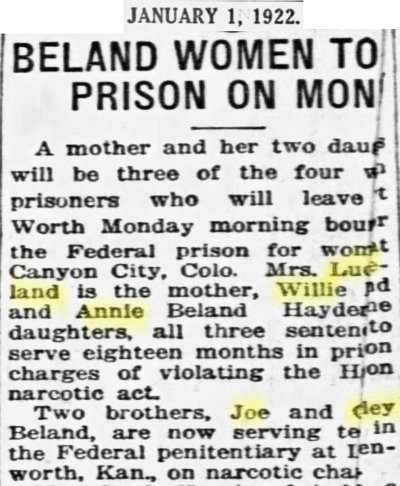

As the year 1922 began, Ma Beland and four of her five children were behind bars—either in prison or in jail awaiting transfer to prison (see Part 1).

As the year 1922 began, Ma Beland and four of her five children were behind bars—either in prison or in jail awaiting transfer to prison (see Part 1).

But they did not stay behind bars long. During the reign of Ma Beland and her mini-Mafia sentences imposed for selling hard drugs—cocaine, morphine, heroin—were light compared with sentences imposed in later years for “gateway” drugs. And women typically received shorter sentences than did men. Thus, Ma Beland and her children spent the 1920s-1940s in a cycle of conviction, short sentence (usually one to three years), release, and rearrest.

For the Ma Beland gang prison gates were revolving doors.

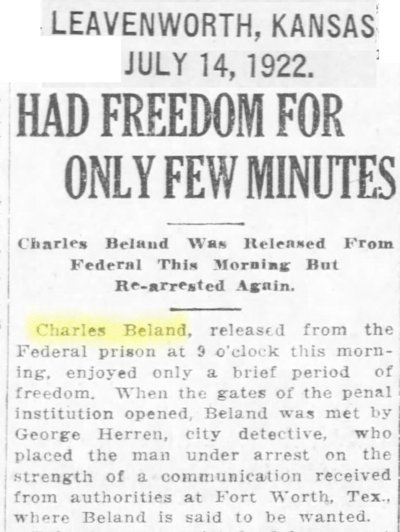

But sometimes those doors revolved really quickly. Six months after Ma Beland and children Annice, Willie, and Joe Jr. went to prison, son Charles was released from Leavenworth but was met outside the prison gates by a police officer who rearrested him on an earlier charge.

But sometimes those doors revolved really quickly. Six months after Ma Beland and children Annice, Willie, and Joe Jr. went to prison, son Charles was released from Leavenworth but was met outside the prison gates by a police officer who rearrested him on an earlier charge.

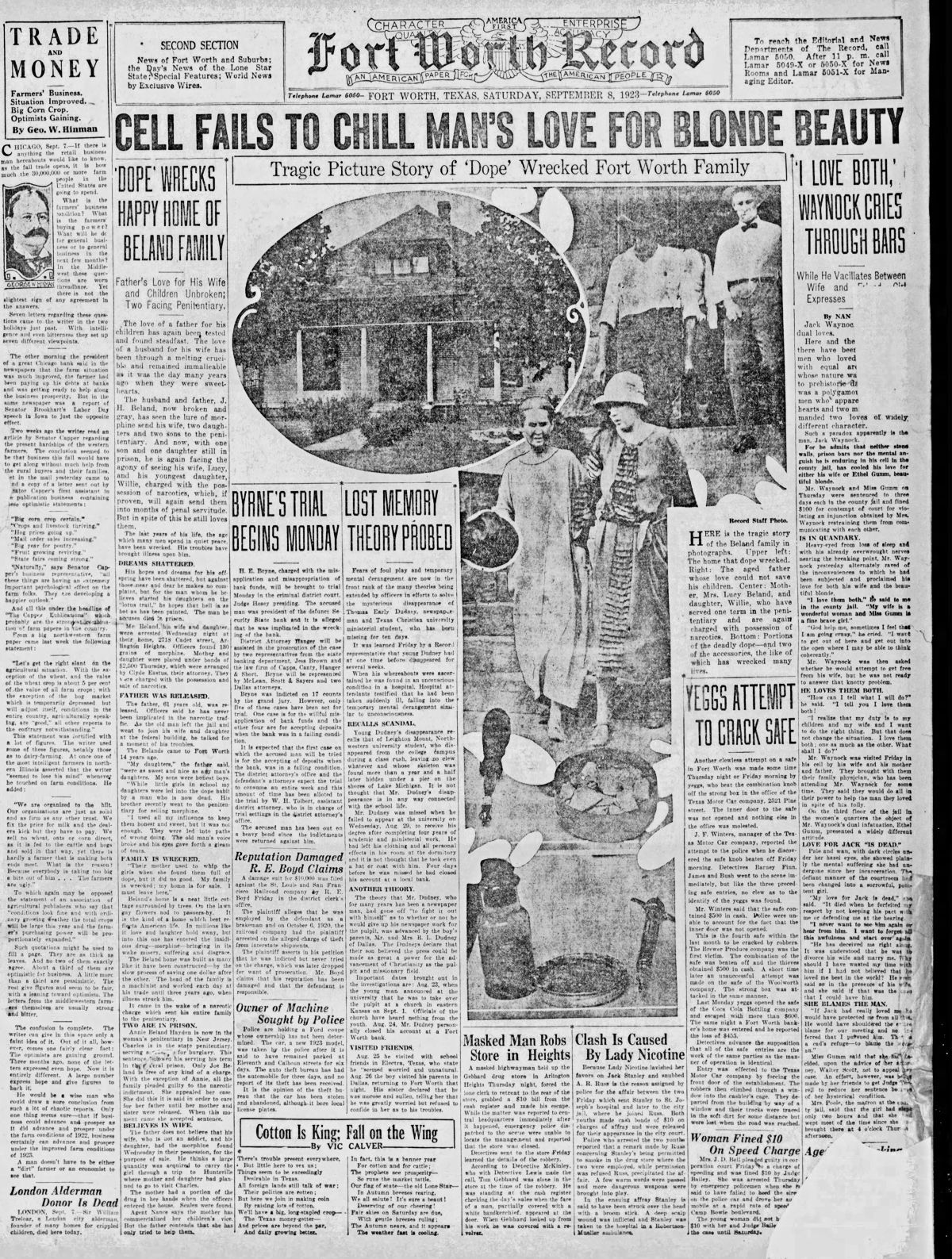

By 1923 the Ma Beland gang was back on the front page of the Star-Telegram. Pictured are Ma and daughter Willie and Ma’s husband Joe Sr. as the three were arrested at their home in Arlington Heights. Narcotics agents seized 180 grains (.4 ounces) of morphine. Ma and Willie were charged with selling narcotics.

By 1923 the Ma Beland gang was back on the front page of the Star-Telegram. Pictured are Ma and daughter Willie and Ma’s husband Joe Sr. as the three were arrested at their home in Arlington Heights. Narcotics agents seized 180 grains (.4 ounces) of morphine. Ma and Willie were charged with selling narcotics.

Joe Sr. was released. Indeed, the Beland children always said their father was never a participant in his family’s crimes. Joe Sr. expressed frustration that a father’s love was no antidote to narcotics.

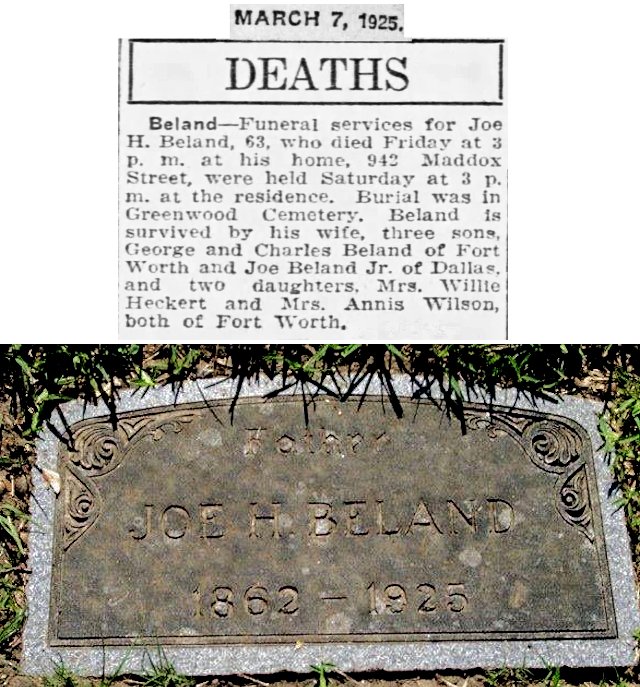

In 1925 Joe Sr. died. He was buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

In 1925 Joe Sr. died. He was buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

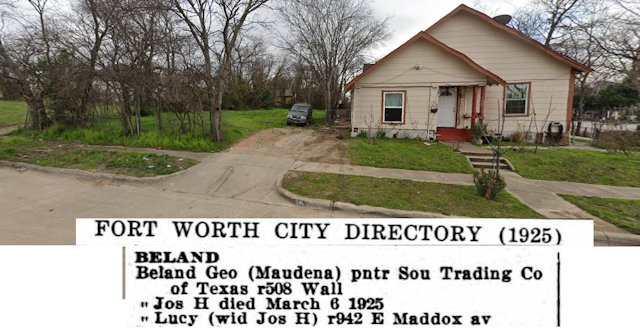

The Belands were living at 942 East Maddox Street. Today a vacant lot stands where the four-room wood-frame house had stood.

The Belands were living at 942 East Maddox Street. Today a vacant lot stands where the four-room wood-frame house had stood.

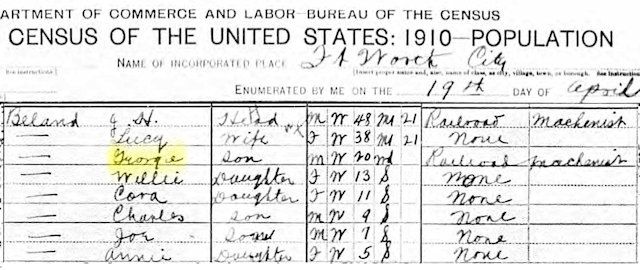

See the entry for George Beland, age twenty, in the 1925 city directory?

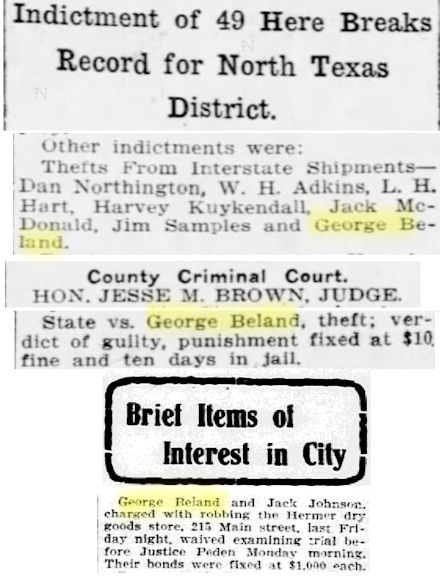

George was the forgotten Beland child, the only one who avoided becoming a career criminal. George Thomas Beland was the oldest sibling, born in 1892. As a young man he was arrested a few times for theft but early on moved away from the influence of his family. He would work as a painter, garage manager, and liquor store operator and lead a life out of the headlines.

George was the forgotten Beland child, the only one who avoided becoming a career criminal. George Thomas Beland was the oldest sibling, born in 1892. As a young man he was arrested a few times for theft but early on moved away from the influence of his family. He would work as a painter, garage manager, and liquor store operator and lead a life out of the headlines.

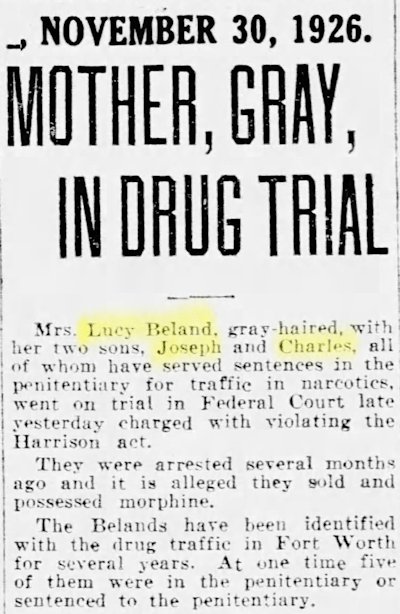

By 1926 daughter Annice was still in prison, but Ma, Joe Jr., Charles, and Willie had been released. But the revolving doors never stopped turning for long. Later in 1926 Ma, Joe Jr., and Charles went back to prison for drug trafficking. Ma was sentenced to a year and a day at the women’s prison in Frankfort, Kentucky.

By 1926 daughter Annice was still in prison, but Ma, Joe Jr., Charles, and Willie had been released. But the revolving doors never stopped turning for long. Later in 1926 Ma, Joe Jr., and Charles went back to prison for drug trafficking. Ma was sentenced to a year and a day at the women’s prison in Frankfort, Kentucky.

Joe Jr. and Charles rode the Leavenworth Trail north to serve two years.

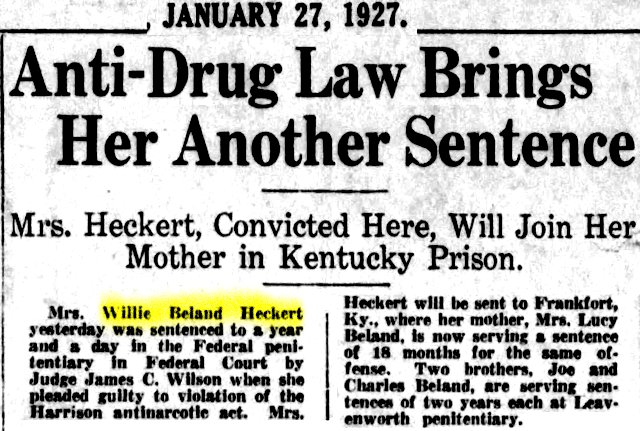

In 1927 it was Willie’s turn. She joined her mother in Frankfort.

In 1927 it was Willie’s turn. She joined her mother in Frankfort.

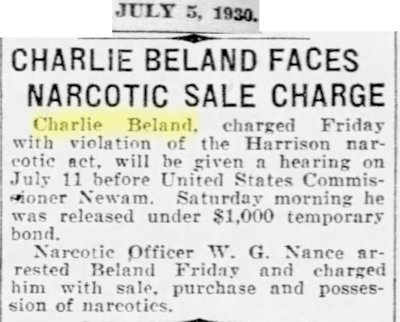

In July 1930 Charles was again arrested for a narcotics violation and freed on bond.

In July 1930 Charles was again arrested for a narcotics violation and freed on bond.

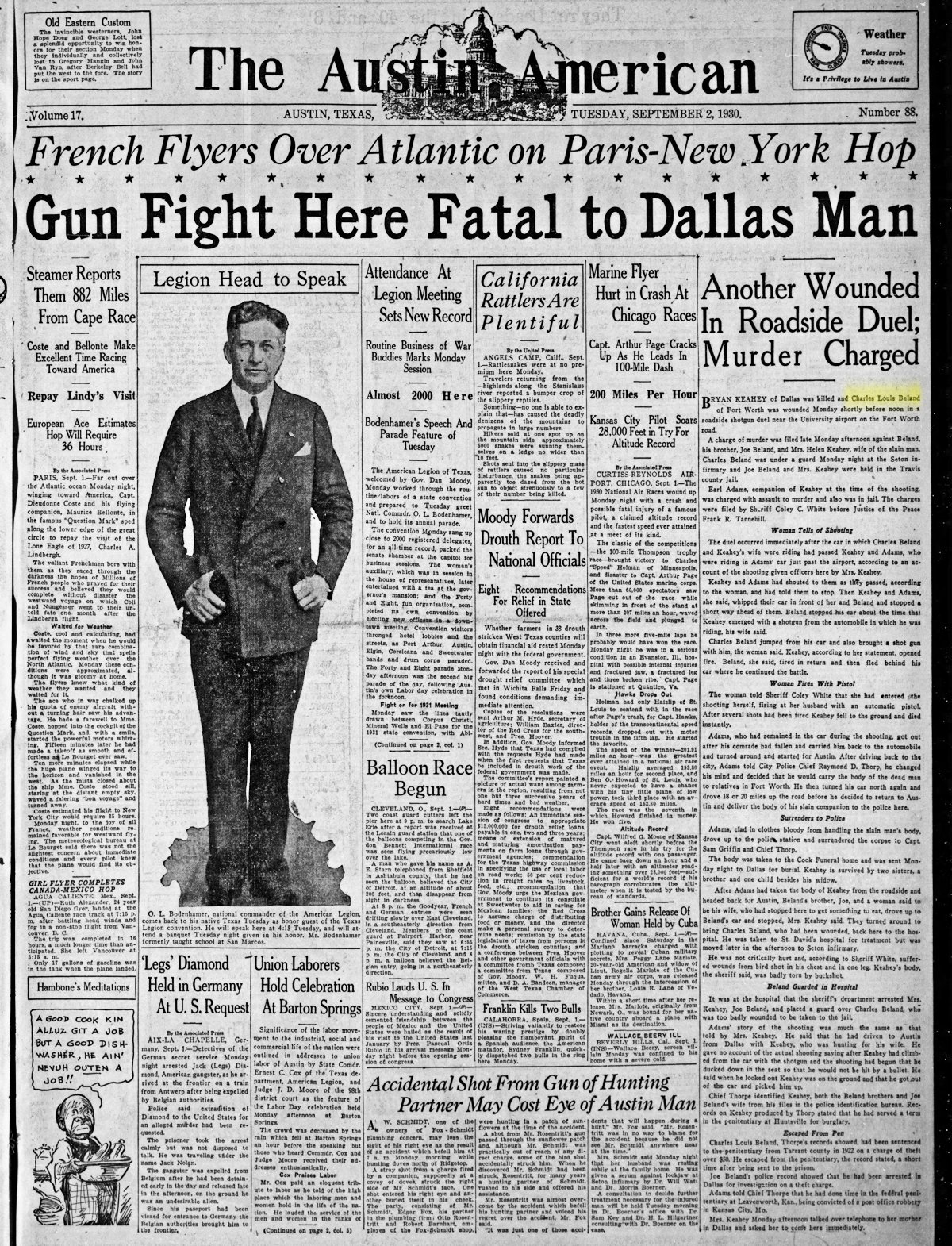

Two months later he apparently was still free on bond. On September 1, 1930 Dallas bootlegger and car thief Bryan Keahey was driving around looking for his wife. Outside Austin on the road to Fort Worth he found her: in a car being driven by Charles Beland. Keahey pulled alongside the Beland car and shouted at Beland, told him to stop.

Two months later he apparently was still free on bond. On September 1, 1930 Dallas bootlegger and car thief Bryan Keahey was driving around looking for his wife. Outside Austin on the road to Fort Worth he found her: in a car being driven by Charles Beland. Keahey pulled alongside the Beland car and shouted at Beland, told him to stop.

Beland stopped.

Keahey stopped.

Beland got out of his car with a shotgun.

Keahey got out of his car with a shotgun.

Keahey began firing at Beland.

Beland began firing at Keahey.

Mrs. Keahey, armed with a pistol, began firing at Mr. Keahey.

Mr. Keahey was outnumbered—to death.

Beland was injured.

Beland recovered, was charged with murder. But I find no resolution of the case in newspapers. Either Beland never went to trial or was acquitted on a plea of self-defense because Keahey had fired first.

beland 1935 joe and charles sentenced od stevens.jpg

Fast-forward five years. In 1935, as six defendants were being sentenced in the O. D. Stevens case, brothers Charles and Joe Jr. Beland were sent back to Leavenworth for narcotics violations.

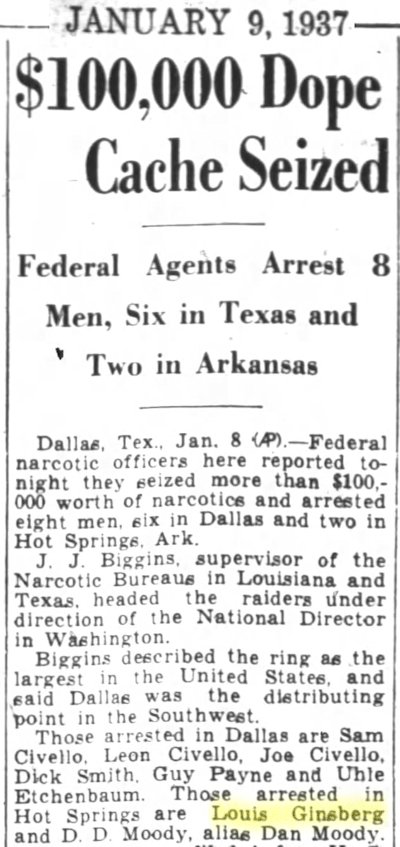

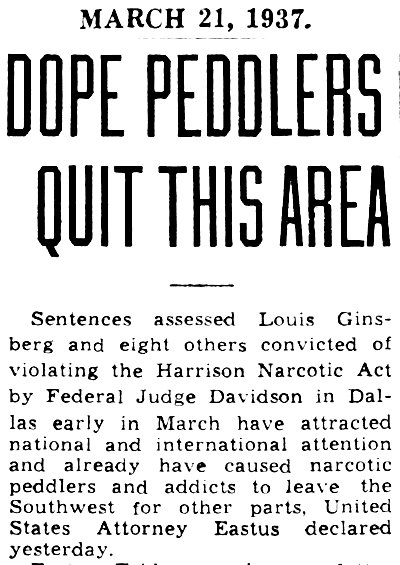

In early 1937 the market position of Ma Beland’s drug ring spiked after federal agents broke up the Ginsberg drug ring in Dallas. Louis Ginsberg was sentenced to fifty-two years in prison—the longest sentence given to that point in a federal narcotics trial.

In early 1937 the market position of Ma Beland’s drug ring spiked after federal agents broke up the Ginsberg drug ring in Dallas. Louis Ginsberg was sentenced to fifty-two years in prison—the longest sentence given to that point in a federal narcotics trial.

The Star-Telegram reported that U.S. Attorney Clyde Eastus said that the sentences assessed in the Ginsberg case had “caused narcotics peddlers and addicts to leave the Southwest for other parts.”

The Star-Telegram reported that U.S. Attorney Clyde Eastus said that the sentences assessed in the Ginsberg case had “caused narcotics peddlers and addicts to leave the Southwest for other parts.”

Not the Belands.

Instead the Belands moved into the vacuum created by the Ginsberg convictions.

Elaine Carey in her book Women Drug Smugglers writes of the Belands: “Their drug operation grew in the 1930s and 1940s, and they distributed and sold heroin, both Asian and Mexican. . . . They had connections to Jewish and Italian organized crime that sold their heroin in the major cities. . . . It is difficult to ascertain if some of the heroin that the Belands distributed came from Lola la Chata.”

Lola la Chata was a major female trafficker of marijuana, heroin, and morphine operating in Mexico.

Carey writes of the Belands: “Their location in Fort Worth places them on a direct transportation line, the eastern Pan-American Highway, sometimes referred to as the Inter-American Highway, which stretches from Mexico City to Pachuca to Monterrey to Nuevo Laredo to San Antonio to Fort Worth, in Texas the I-35 interstate corridor. What officials learned about Charlie Beland . . . was that he had contacts with Mexican organized crime for the purpose of acquiring illegal drugs.”

With the Ginsberg gang shut down, federal narcotics agents turned their attention to the Beland gang.

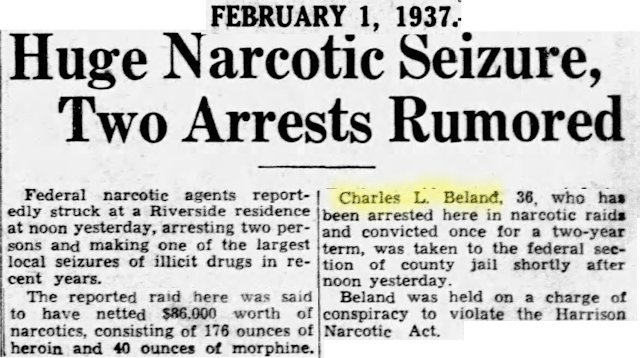

In February 1937 federal agents arrested Charles Beland in “one of the largest local seizures of illicit drugs in recent years.” Agents confiscated 176 ounces of heroin and 40 ounces of morphine with a total value of $86,000 ($158,000 today).

In February 1937 federal agents arrested Charles Beland in “one of the largest local seizures of illicit drugs in recent years.” Agents confiscated 176 ounces of heroin and 40 ounces of morphine with a total value of $86,000 ($158,000 today).

In the criminal world, likes attract. Ma Beland’s sons and daughters married people who either were criminals or were amenable to criminality. Once within the gravitational pull of Ma Beland’s influence, her children-in-law also went to prison for narcotics offenses.

In the criminal world, likes attract. Ma Beland’s sons and daughters married people who either were criminals or were amenable to criminality. Once within the gravitational pull of Ma Beland’s influence, her children-in-law also went to prison for narcotics offenses.

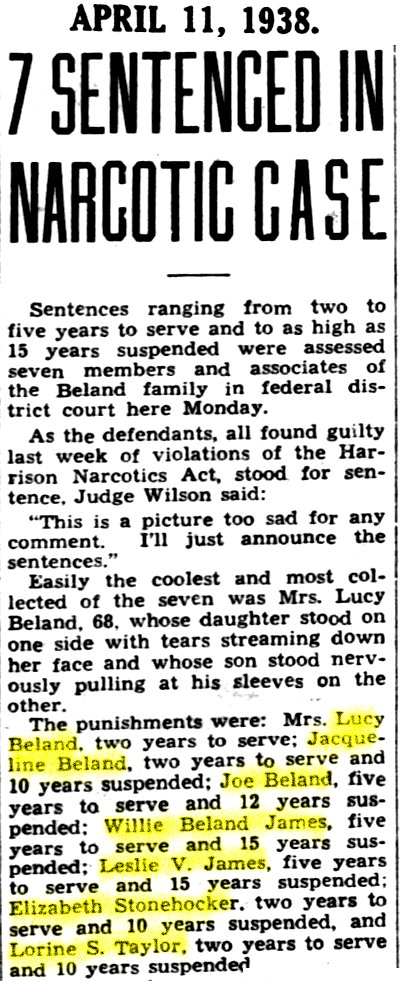

In November 1937 federal narcotics agents arrested Ma Beland, son Joe Jr., and daughter Willie. Also arrested were Joe Jr.’s wife Jacqueline and Willie’s husband Leslie.

Friends of the Beland family also occasionally were sucked into the Beland vortex. Also arrested in 1937 were friends Elizabeth Stonehocker and Lorine Taylor.

In 1938 three Belands, two spouses, and two friends were sentenced for selling 3,019 grains (6.9 ounces) of morphine.

Also going to prison on other occasions were son Charles’s wife Esther and daughter Annice’s husband Francis.

The Ma Beland gang at its peak numbered thirteen Belands, spouses, and friends.

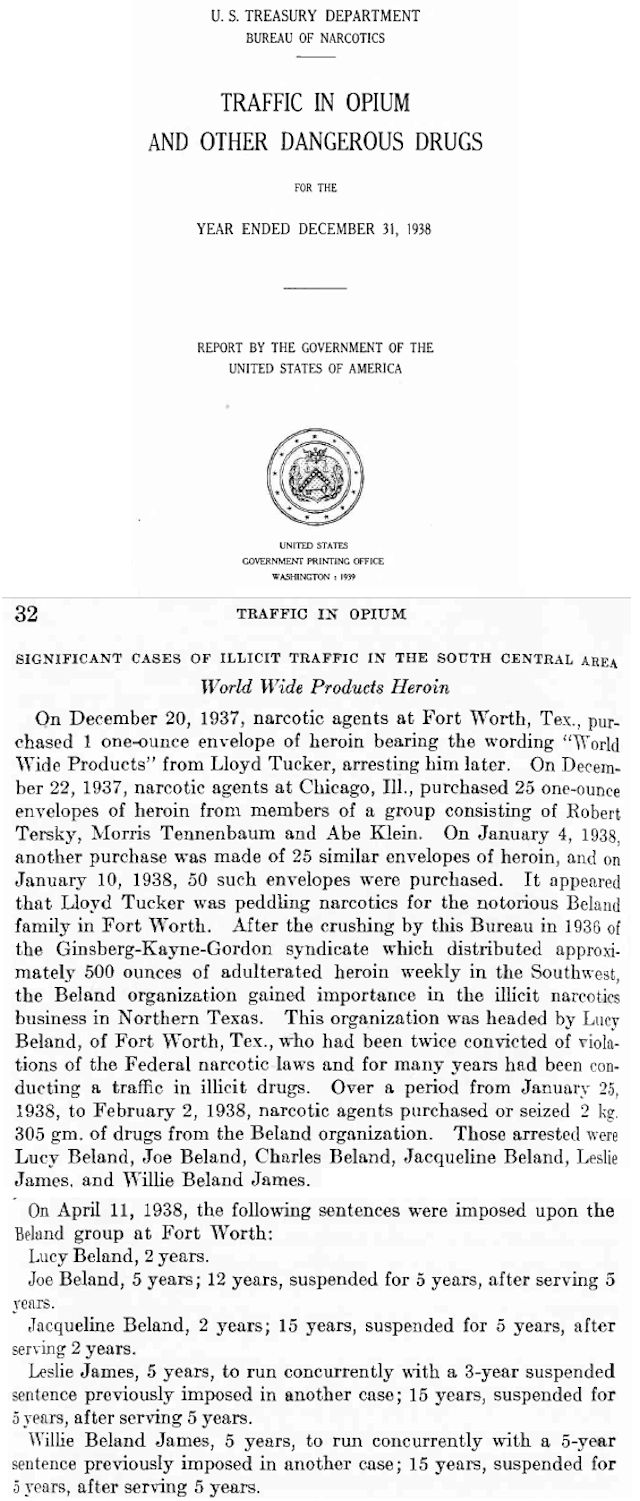

In 1939 the League of Nations received a report on drug trafficking from the Federal Narcotics Bureau. The report said that in 1937 narcotics agents in Fort Worth and Chicago purchased heroin in envelopes stamped “World Wide Products.” The bureau traced these envelopes to “the notorious Beland family.” The Green Dragon drug ring (see below), of which Charles Beland was a member, also sometimes stamped its heroin packets “World Wide Products.” During one week in 1938 federal agents bought or seized two kilograms of narcotics from the Belands. The report said that after federal agents broke up the Louis Ginsberg drug ring, Ma Beland’s gang “gained importance in the illicit narcotics business in Northern Texas.”

In 1939 the League of Nations received a report on drug trafficking from the Federal Narcotics Bureau. The report said that in 1937 narcotics agents in Fort Worth and Chicago purchased heroin in envelopes stamped “World Wide Products.” The bureau traced these envelopes to “the notorious Beland family.” The Green Dragon drug ring (see below), of which Charles Beland was a member, also sometimes stamped its heroin packets “World Wide Products.” During one week in 1938 federal agents bought or seized two kilograms of narcotics from the Belands. The report said that after federal agents broke up the Louis Ginsberg drug ring, Ma Beland’s gang “gained importance in the illicit narcotics business in Northern Texas.”

By 1940 Ma Beland was seventy years old. Her husband and one daughter were dead. For the Ma Beland gang the 1940s were relatively quiet as her lieutenants, sons Joe Jr. and Charles, were being locked up for ever-longer prison sentences.

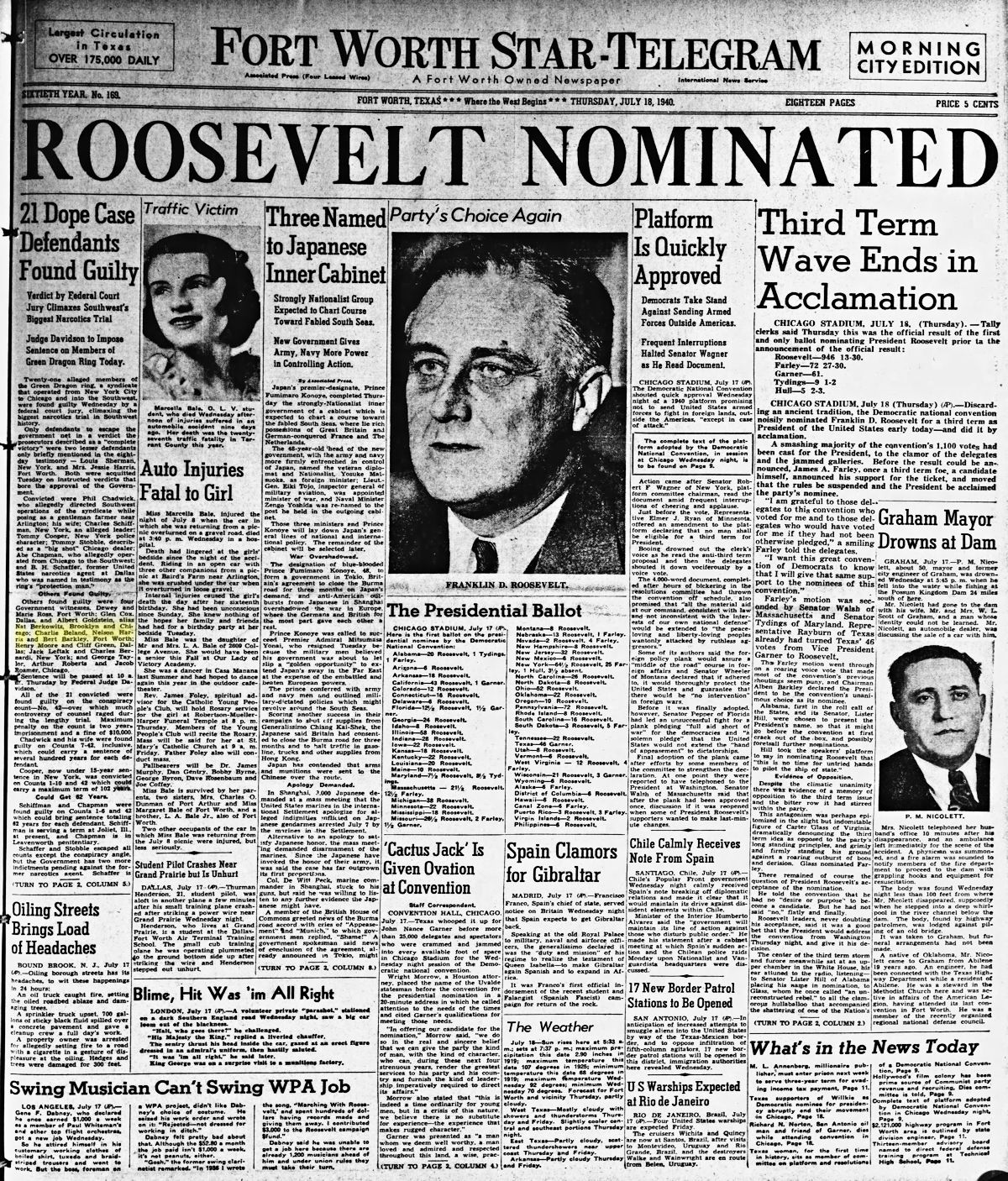

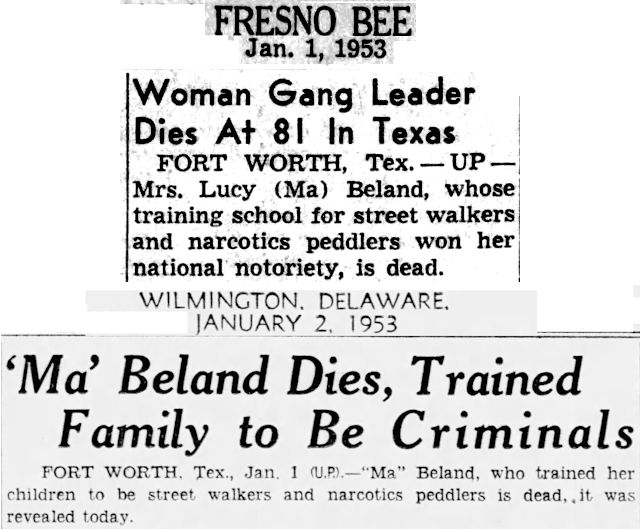

In addition to his mother’s drug ring, Charles Beland had a side gig. In 1940 he was one of twenty-one members of the Green Dragon drug ring found guilty in what the Star-Telegram called “the biggest narcotics trial in Southwest history.” Charles Beland was sentenced to five years in Leavenworth and a ten-year suspended sentence.

In addition to his mother’s drug ring, Charles Beland had a side gig. In 1940 he was one of twenty-one members of the Green Dragon drug ring found guilty in what the Star-Telegram called “the biggest narcotics trial in Southwest history.” Charles Beland was sentenced to five years in Leavenworth and a ten-year suspended sentence.

Also found guilty was Nelson Harris, whose car-bomb murder ten years later would expose Fort Worth’s underworld. Harris was sentenced to two years in prison.

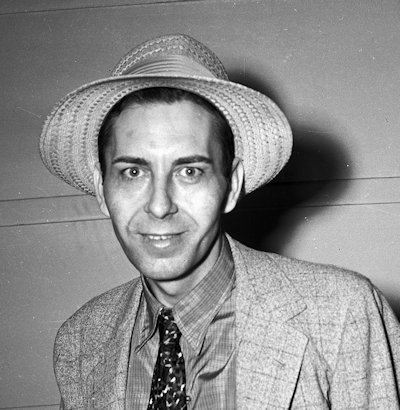

Charles Beland during the Green Dragon trial. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library Star-Telegram Collection.)

Charles Beland during the Green Dragon trial. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library Star-Telegram Collection.)

In 1941 Charles Beland was declared a habitual criminal because of three narcotics convictions in fifteen years. His Green Dragon sentence was increased to seven years. But old habits die hard. According to author Carey, Charles was transferred from Leavenworth to Alcatraz because he had been smuggling drugs in Leavenworth.

After the Green Dragon trial of 1940 Ma Beland’s gang stayed mostly out of the headlines during the 1940s. In 1947 son Joe Jr. went back to Leavenworth; daughter Willie went back to prison for three years for stealing $200 from a drugstore in Handley. Daughter Annice was arrested for shoplifting and selling heroin.

If the 1940s were relatively quiet for Ma Beland and her gang, the 1950s were as quiet as a tomb.

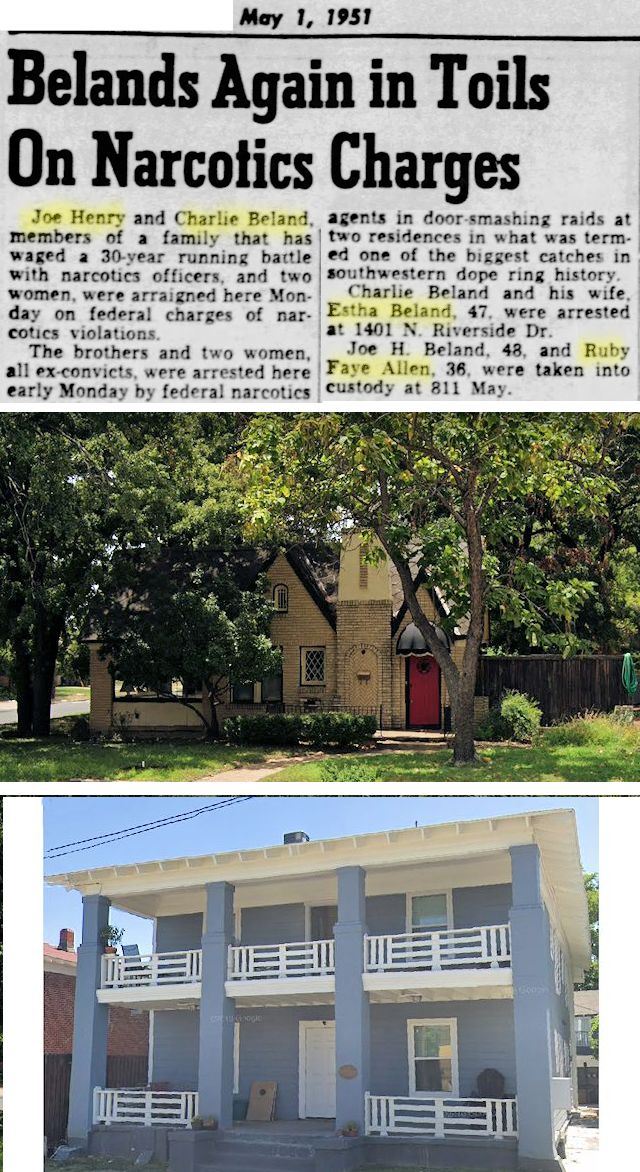

In a last hurrah, in early 1951 Joe and Charles were arrested yet again in what the Star-Telegram called “one of the biggest catches in southwestern drug ring history.” Also arrested were Charles’s wife Esther and Joe’s girlfriend Ruby Faye Allen. Narcotics agents broke down the front doors of houses at 1401 North Riverside Drive and 811 May Street (pictured) to gain entry. Agents then broke down two bathroom doors and found the two women flushing heroin down the toilets. Guns, brass knuckles, and hypodermic syringes were confiscated.

In a last hurrah, in early 1951 Joe and Charles were arrested yet again in what the Star-Telegram called “one of the biggest catches in southwestern drug ring history.” Also arrested were Charles’s wife Esther and Joe’s girlfriend Ruby Faye Allen. Narcotics agents broke down the front doors of houses at 1401 North Riverside Drive and 811 May Street (pictured) to gain entry. Agents then broke down two bathroom doors and found the two women flushing heroin down the toilets. Guns, brass knuckles, and hypodermic syringes were confiscated.

Charles and Ruby Faye were sentenced to five years in prison. Allen had a criminal record dating back to 1925.

The Star-Telegram wrote that W. A. Heddens, agent in charge of the Federal Narcotics Bureau in Fort Worth, said Charles Beland was “one of Fort Worth’s biggest dope peddlers and at one time one of the biggest peddlers in the Southwest.”

Charles’s attorney told the court that his client was an addict who chose to sell narcotics to finance his habit rather than rob or steal.

Charles would travel the Leavenworth Trail north one final time, but he would travel it alone.

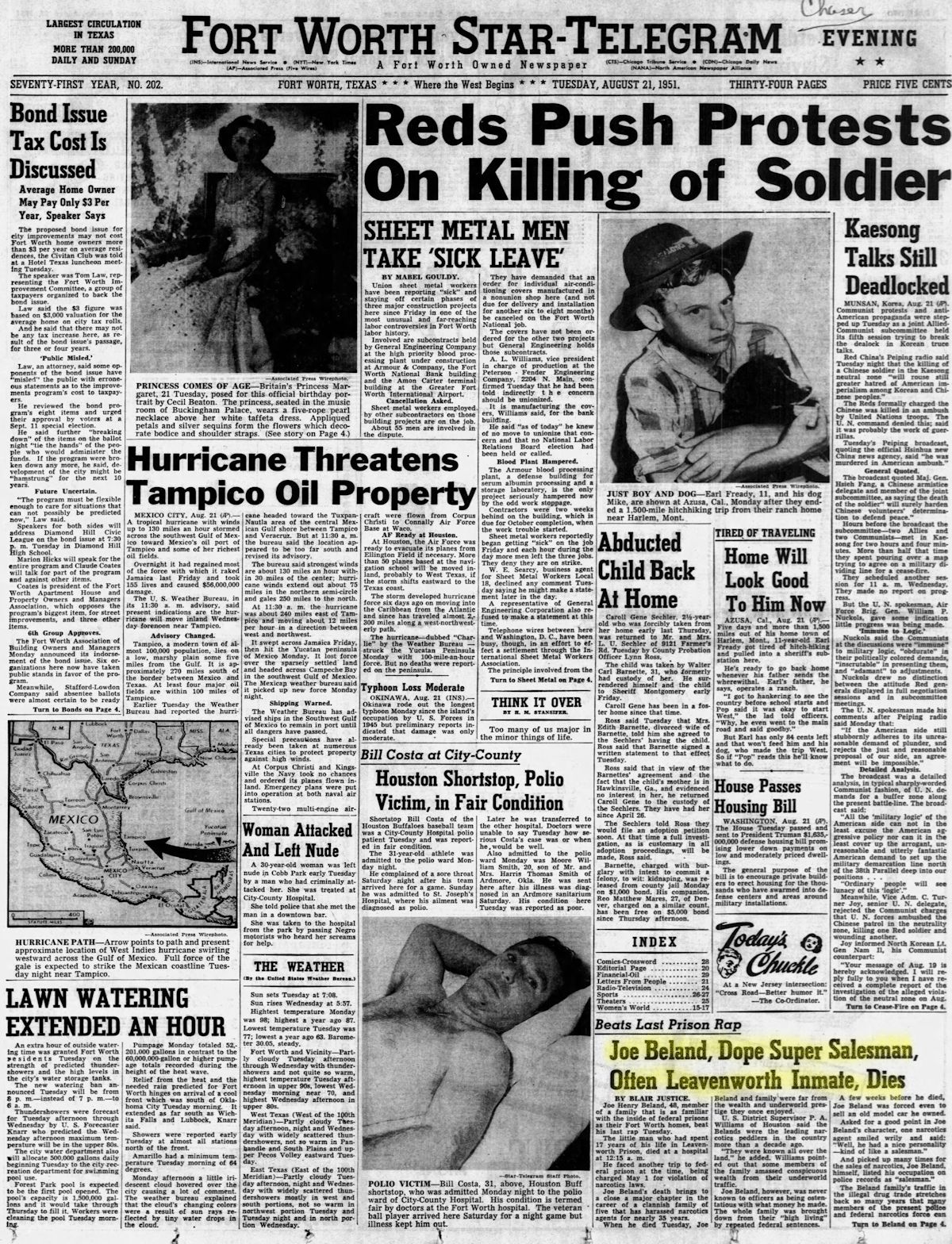

Charles’s brother Joe Jr. (“dope super salesman”) died before he could be sent back up the Leavenworth Trail. Joe Jr. had spent seventeen of his forty-eight years in Leavenworth over six sentences. After one conviction, Joe became so impatient with the government’s delay in transporting him to Leavenworth to begin a new sentence that he paid his own way north so he could start serving his time.

Charles’s brother Joe Jr. (“dope super salesman”) died before he could be sent back up the Leavenworth Trail. Joe Jr. had spent seventeen of his forty-eight years in Leavenworth over six sentences. After one conviction, Joe became so impatient with the government’s delay in transporting him to Leavenworth to begin a new sentence that he paid his own way north so he could start serving his time.

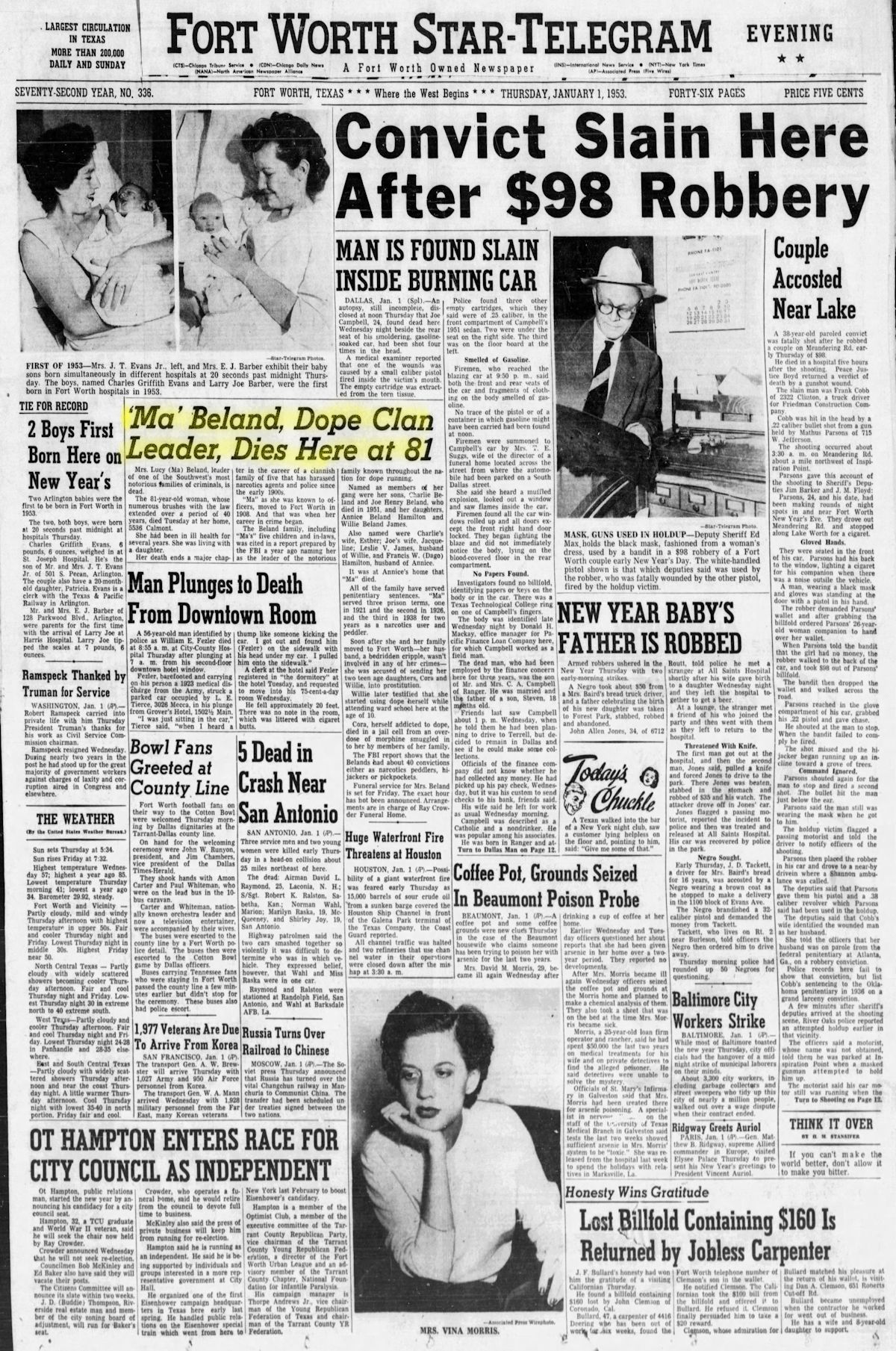

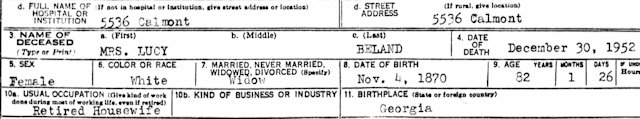

Lucy Beland, the godmother of Fort Worth’s mini-Mafia, died on December 30, 1952 at age eighty-one.

Lucy Beland, the godmother of Fort Worth’s mini-Mafia, died on December 30, 1952 at age eighty-one.

Her death certificate lists her as a “retired housewife.”

Her death certificate lists her as a “retired housewife.”

The Godmother’s death was news from coast to coast.

The Godmother’s death was news from coast to coast.

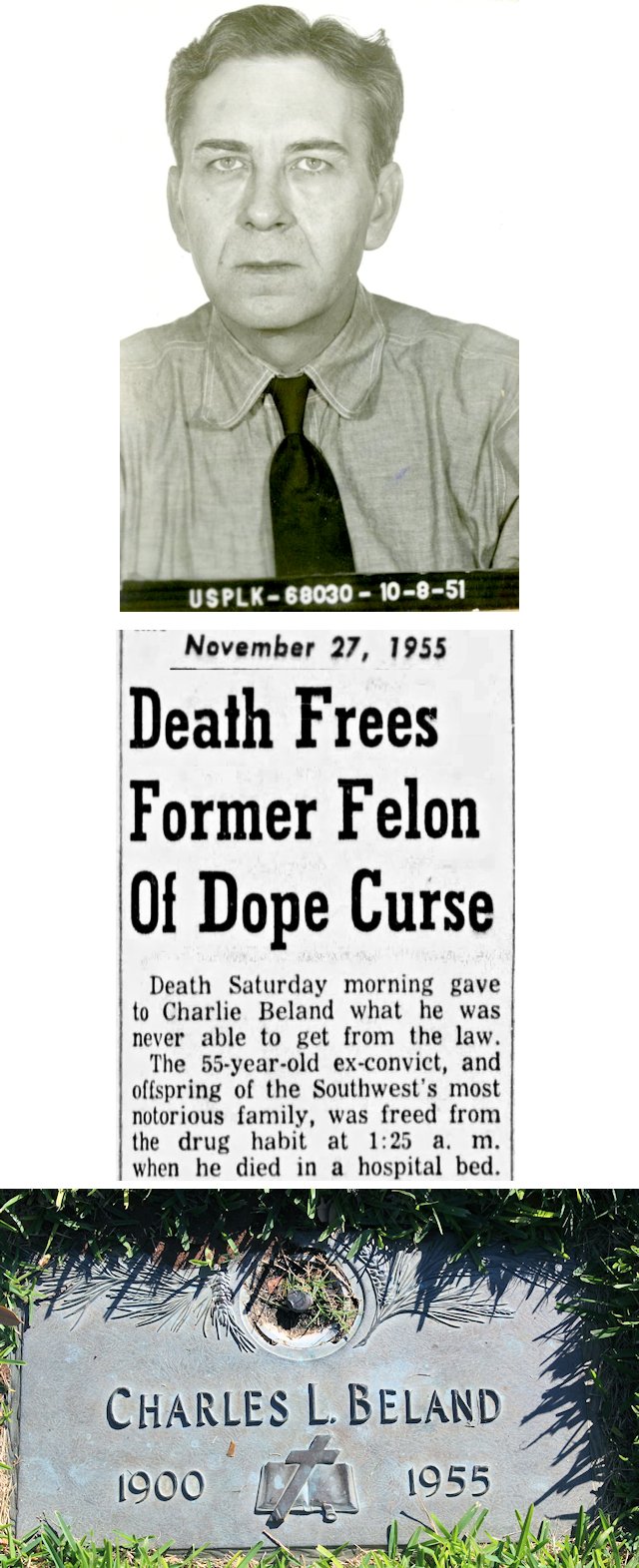

Son Charles died in 1955 at age fifty-five. Since 1944 he had spent most of his life in prison. Charles Beland is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Son Charles died in 1955 at age fifty-five. Since 1944 he had spent most of his life in prison. Charles Beland is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

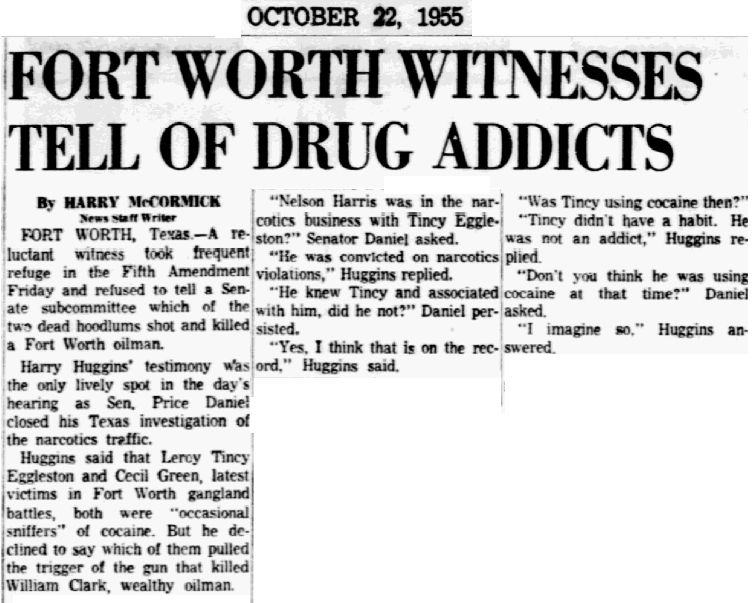

Also in 1955 the U.S. Senate sent a subcommittee to Fort Worth to investigate local gangland narcotics trafficking. Senator Price Daniel questioned Harry Huggins, one of three men charged in the murder of millionaire William P. Clark. Daniel asked Huggins about the two other suspects in the Clark murder—Tincy Eggleston and Cecil Green, both of whom had recently been killed in gang-style slayings.

Also in 1955 the U.S. Senate sent a subcommittee to Fort Worth to investigate local gangland narcotics trafficking. Senator Price Daniel questioned Harry Huggins, one of three men charged in the murder of millionaire William P. Clark. Daniel asked Huggins about the two other suspects in the Clark murder—Tincy Eggleston and Cecil Green, both of whom had recently been killed in gang-style slayings.

Senator Daniel also asked Federal Narcotics Bureau agent W. A. Heddens if he knew of any instances of whole families becoming addicted to narcotics. In replying Heddens inadvertently pronounced “ashes to ashes, dust to dust” over the Ma Beland gang.

Heddens said: “Because we are in Fort Worth I am thinking of the Beland family. The mother, Mrs. Lucy Beland, her three daughters, and two sons, as well as the men and women who married into the family, all became addicted. At one time the whole family was in prison for narcotics law violations. There is no further evidence that this family is trafficking in dope, and only a few of them are left.”

Willie Beland died in 1956.

Willie Beland died in 1956.

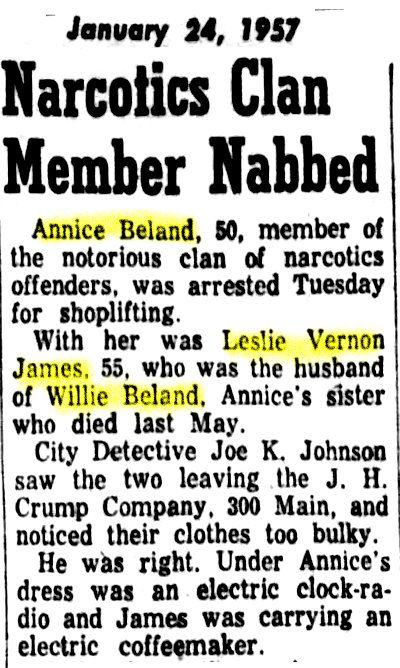

In 1957, forty years after Ma Beland taught her daughters how to shoplift, Annice Beland, the youngest of the Beland children, was arrested for stealing a clock radio from a Crump store. Arrested with Annice was the husband of her late sister Willie.

In 1957, forty years after Ma Beland taught her daughters how to shoplift, Annice Beland, the youngest of the Beland children, was arrested for stealing a clock radio from a Crump store. Arrested with Annice was the husband of her late sister Willie.

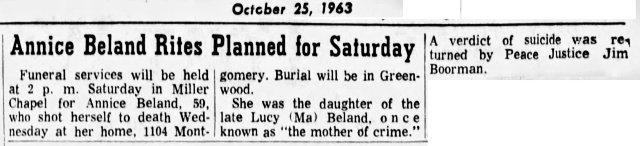

Six years later Annice committed suicide.

Six years later Annice committed suicide.

That closed the book on the Ma Beland gang. After more than thirty years of selling heroin, morphine, and cocaine, when the snow settled Ma Beland had been sentenced to federal prison three times; son Charles five times; son Joe Jr. six times, daughter Willie seven times.

In all, the FBI counted forty convictions for the gang over the years, mostly for narcotics but also for hijacking. The Star-Telegram said the FBI at one time considered the family to be “the nation’s leading dope runners.”

During most of the time from 1920 to 1955 at least one Beland—and often more than one—was in prison.

With the death of Annice, and then there was one.

With the death of Annice, and then there was one.

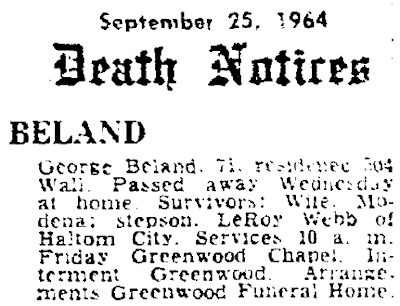

Remember Ma Beland’s first-born son, George? He had escaped the influence of his mother and his siblings and lived a long and lawful life. He died in 1964, the white sheep of the family and the last Beland standing.

(Thanks to Justin Tate and Donna Humphrey Donnell for their help.)

I wonder if we’re related ?