On Friday, July 2, 1915 Frank Holt traveled by train from New York City to Washington, D.C.

And thus did he begin his busy Fourth of July weekend.

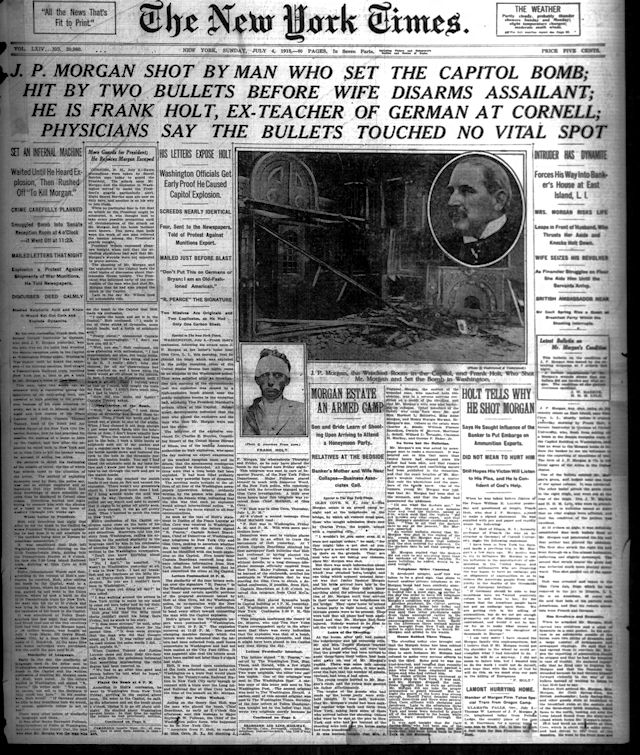

Three days later, on Independence Day 1915, America awoke to unsettling front-page headlines:

The front page of the New York Times said Frank Holt, a former teacher at Cornell University, had shot financier J. P. Morgan Jr. and bombed the U.S. Capitol building.

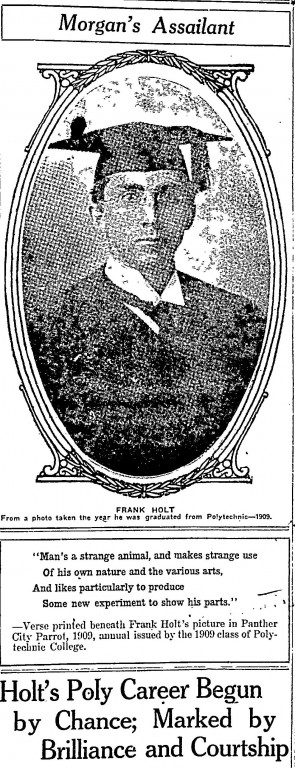

The front page of the Star-Telegram carried the same news but added some details. In Polytechnic, readers were drawn especially to the photo and headline in the middle of the page:

The front page of the Star-Telegram carried the same news but added some details. In Polytechnic, readers were drawn especially to the photo and headline in the middle of the page:

On that Fourth of July 106 years ago Frank Holt, who a few years earlier had been first a student and then a teacher at Polytechnic College (now Texas Wesleyan University) and had married the daughter of a local Methodist church leader and president of the college’s board of trustees, was in jail after a red, white, and kablooey spree over the Fourth of July weekend. But no firecrackers and bottle rockets for Frank Holt, no siree, Bob. He planted a time bomb that damaged the U.S. Capitol building, talked his way into the mansion of financier J. P. Morgan Jr. and shot him, and planted a time bomb that damaged a ship carrying munitions to England.

On that Fourth of July 106 years ago Frank Holt, who a few years earlier had been first a student and then a teacher at Polytechnic College (now Texas Wesleyan University) and had married the daughter of a local Methodist church leader and president of the college’s board of trustees, was in jail after a red, white, and kablooey spree over the Fourth of July weekend. But no firecrackers and bottle rockets for Frank Holt, no siree, Bob. He planted a time bomb that damaged the U.S. Capitol building, talked his way into the mansion of financier J. P. Morgan Jr. and shot him, and planted a time bomb that damaged a ship carrying munitions to England.

Photo from Wikipedia shows bomb damage to the U.S. Capitol.

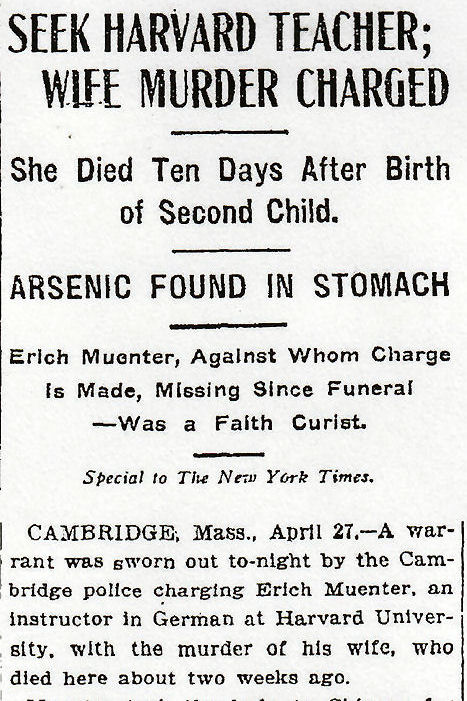

Let’s dust ourselves off and back up. Frank Holt was born “Erich Muenter” in Germany in 1871. He came to America in 1890 and married in 1901. A skilled linguist, by 1904 he was a student and tutor at Harvard University.

But in 1906 Muenter’s first wife died shortly after childbirth. An autopsy revealed arsenic poisoning. Muenter was charged with murder but had disappeared—taking his two children and his wife’s body with him. From Boston Muenter apparently went first to Chicago, where he cremated his wife’s body and left his two children with his sister. Then he went to Mexico, where he worked as a stenographer. In 1908 he left Mexico headed for Chicago, possibly to see his children. But passing through Fort Worth, Muenter got off the train and for some reason boarded a streetcar that took him to Polytechnic College. He met two members of the faculty, introduced himself as “Frank Holt.” The two Polytechnic men were impressed with the language abilities of young Holt and invited him to enroll at their college. He did.

But in 1906 Muenter’s first wife died shortly after childbirth. An autopsy revealed arsenic poisoning. Muenter was charged with murder but had disappeared—taking his two children and his wife’s body with him. From Boston Muenter apparently went first to Chicago, where he cremated his wife’s body and left his two children with his sister. Then he went to Mexico, where he worked as a stenographer. In 1908 he left Mexico headed for Chicago, possibly to see his children. But passing through Fort Worth, Muenter got off the train and for some reason boarded a streetcar that took him to Polytechnic College. He met two members of the faculty, introduced himself as “Frank Holt.” The two Polytechnic men were impressed with the language abilities of young Holt and invited him to enroll at their college. He did.

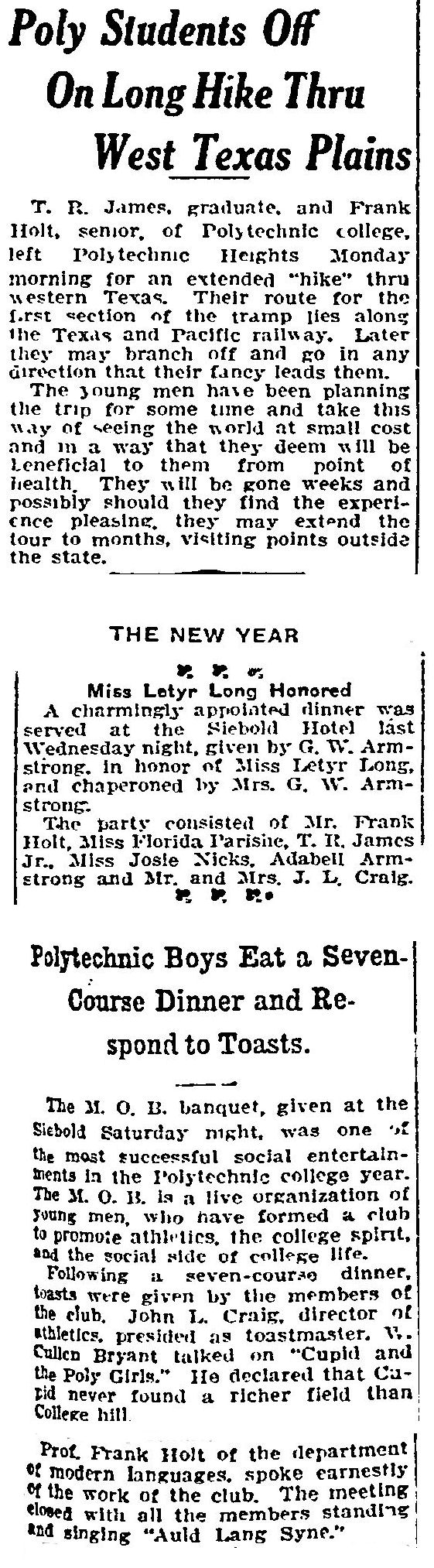

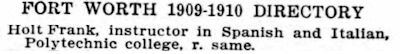

While at Polytechnic College, Holt lived an apparently normal life as student and teacher, as these clips show. He belonged to campus organizations and was senior class poet. However, one colleague later remembered that Holt had been an unpopular teacher among students, and Holt was disciplined once for having a pistol in his room on campus. (T. R. James was the son of William James, for whom the Poly junior high school is named.)

While at Polytechnic College, Holt lived an apparently normal life as student and teacher, as these clips show. He belonged to campus organizations and was senior class poet. However, one colleague later remembered that Holt had been an unpopular teacher among students, and Holt was disciplined once for having a pistol in his room on campus. (T. R. James was the son of William James, for whom the Poly junior high school is named.)

Frank Holt taught Spanish and Italian.

Frank Holt taught Spanish and Italian.

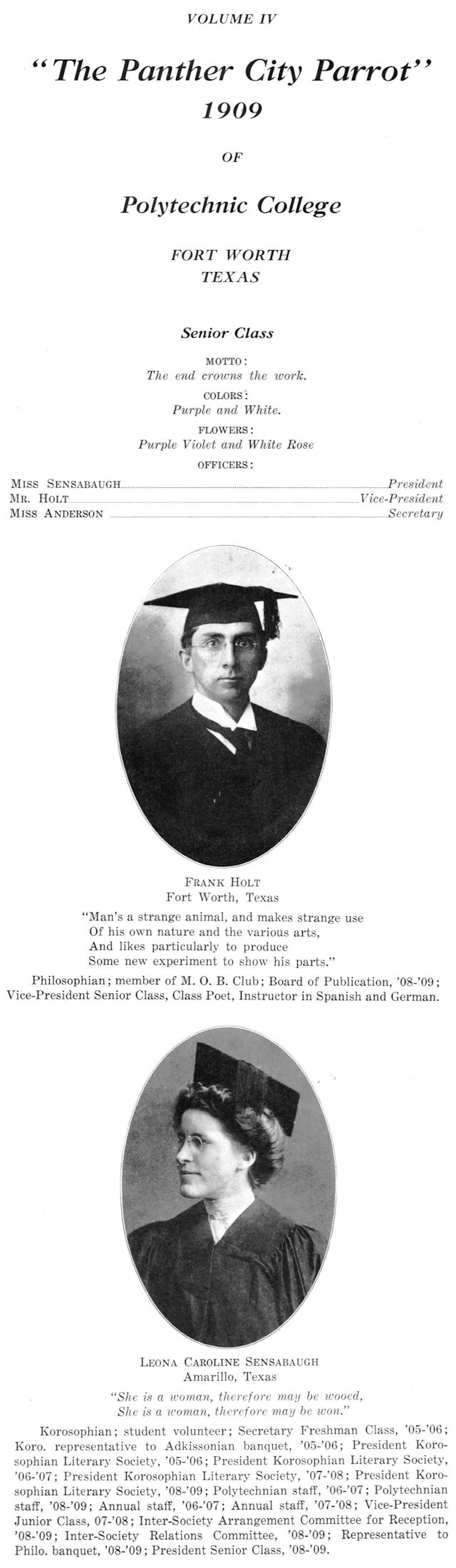

In 1909 Frank was vice president of the senior class. Class president was Leona Sensabaugh.

In 1909 Frank was vice president of the senior class. Class president was Leona Sensabaugh.

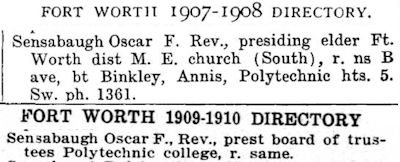

Leona was the daughter of the Reverend Oscar F. Sensabaugh, presiding elder of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Fort Worth, president of the board of trustees of Polytechnic College, and later one of the founders of SMU in Dallas.

Frank and Leona had met at the college in 1908, shared an affinity for languages. Frank and Leona graduated in 1909, and Frank applied for a professorship at Polytechnic College. He was denied because he was secretive about his past when interviewed.

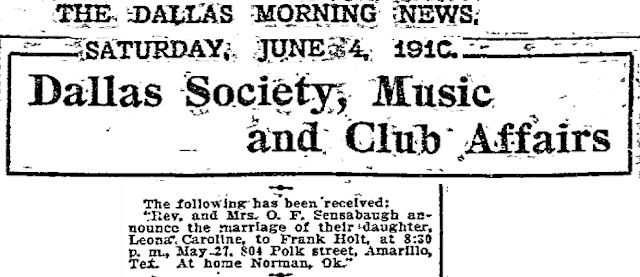

In 1910 Frank and Leona were married by her father. The newlyweds lived on Avenue B in Poly. Clip is from the June 4 Dallas Morning News.

In 1910 Frank and Leona were married by her father. The newlyweds lived on Avenue B in Poly. Clip is from the June 4 Dallas Morning News.

From Poly Frank and Leona moved on. He spent a year teaching at the University of Oklahoma; she spent a year in Cuba. Then he taught at Vanderbilt and was at Cornell in 1914 when World War I broke out between his native Germany and the Allied powers. Although the United States was not yet fighting, it was supplying goods, including munitions, to the Allied powers. But Cornell colleagues later remembered that Holt had not expressed radical antiwar or pro-Germany feelings.

He soon would.

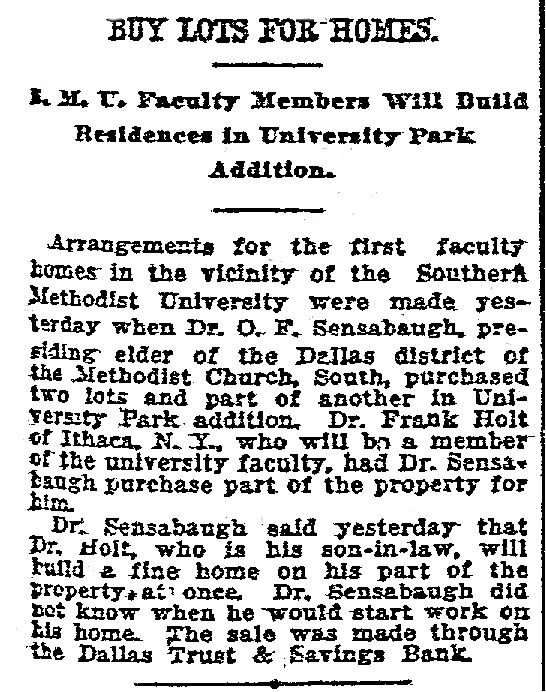

By the summer of 1915 Frank Holt had ended his teaching term at Cornell in Ithaca, New York and had accepted a position to teach French at the new Methodist university opening in Dallas that autumn. His father-in-law, by then presiding elder of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Dallas, was arranging housing. Holt’s wife and children had already gone to Dallas.

By the summer of 1915 Frank Holt had ended his teaching term at Cornell in Ithaca, New York and had accepted a position to teach French at the new Methodist university opening in Dallas that autumn. His father-in-law, by then presiding elder of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Dallas, was arranging housing. Holt’s wife and children had already gone to Dallas.

But when Frank Holt left Ithaca in the summer of 1915 he traveled not to Dallas but to New York City, where he filled an ominous shopping list: 120 pounds of dynamite, blasting caps, batteries, acid, fuses. By the Independence Day weekend he was ready. On Friday, July 2, he traveled by train to Washington, where he planted a suitcase time bomb in the Senate wing of the Capitol Building. He then mailed letters to newspaper editors explaining the motive behind what was to come: to demonstrate to the American people the damage that such U.S. explosives were doing in the European war (“Will our explosives not become boomerangs? . . . This explosion is the exclamation point to my appeal for peace”).

Holt waited on a bench at a safe distance until he heard the explosion at the Capitol (damage was minor), then returned to New York City. The next day, Saturday, July 3, he boarded a train for Glen Cove, Long Island. At the mansion of J. P. Morgan Jr. Holt presented himself to the butler as “an old friend” of the millionaire industrialist, who was a director of U.S. Steel and the intermediary for British purchases of American goods, including munitions. Holt later said that his plan had been to hold Morgan’s wife and children hostage until Morgan agreed to use his influence to stop the shipment of U.S. arms and to maintain stricter U.S. neutrality in the war.

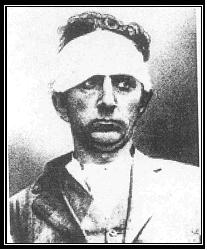

When Morgan and other members of the household charged at the armed intruder, Holt shot Morgan twice. Morgan would recover. Morgan’s butler beat Holt with a chunk of coal. Holt was subdued, arrested, and jailed.

When Morgan and other members of the household charged at the armed intruder, Holt shot Morgan twice. Morgan would recover. Morgan’s butler beat Holt with a chunk of coal. Holt was subdued, arrested, and jailed.

On July 6 in Dallas Holt’s wife received a letter that her husband had mailed on July 2 before he bombed the Capitol. Holt wrote: “The steamer leaving New York for Liverpool on July 3 should sink, God willing, on 7th. I think it is the Philadelphia or the Saxonia, but am not quite sure.” Both ships were owned by J. P. Morgan. Both ships were alerted, searched, and declared safe. But the trans-Atlantic shipping agent to whom Holt had given a package before his arrest had put the package on a different Morgan ship, the Minnehaha, which sailed from New York on the Fourth of July bound for Liverpool with a cargo of munitions.

On July 6 in Dallas Holt’s wife received a letter that her husband had mailed on July 2 before he bombed the Capitol. Holt wrote: “The steamer leaving New York for Liverpool on July 3 should sink, God willing, on 7th. I think it is the Philadelphia or the Saxonia, but am not quite sure.” Both ships were owned by J. P. Morgan. Both ships were alerted, searched, and declared safe. But the trans-Atlantic shipping agent to whom Holt had given a package before his arrest had put the package on a different Morgan ship, the Minnehaha, which sailed from New York on the Fourth of July bound for Liverpool with a cargo of munitions.

On July 7 an explosion rocked the Minnehaha at sea and ignited a fire. The ship returned to port for repairs and after a few days again sailed for England.

On July 7 an explosion rocked the Minnehaha at sea and ignited a fire. The ship returned to port for repairs and after a few days again sailed for England.

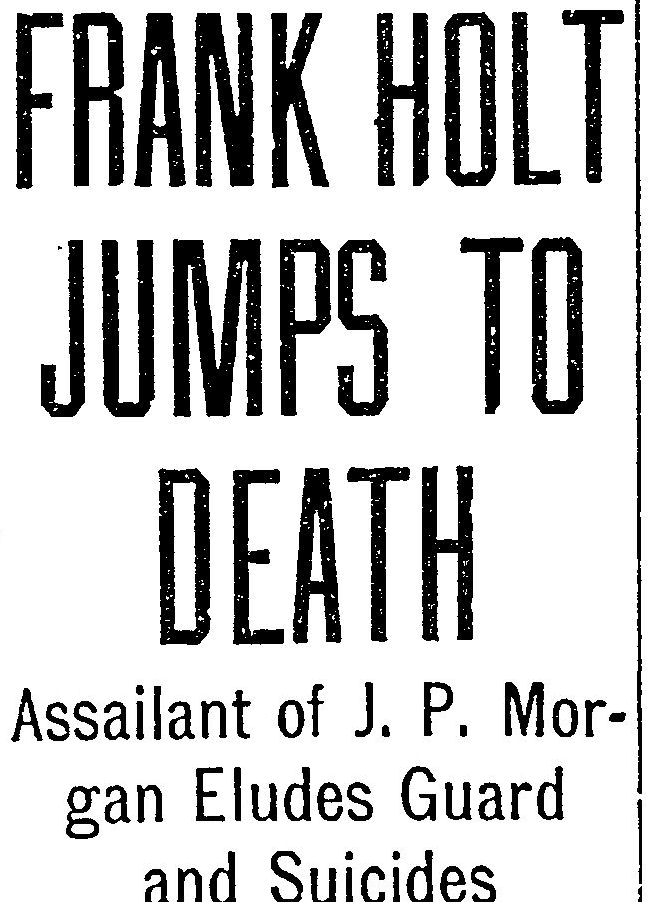

On the day before the Minnehaha explosion, Erich Muenter, who had passed through Poly as “Frank Holt” on his way to infamy, committed suicide in jail.

On the day before the Minnehaha explosion, Erich Muenter, who had passed through Poly as “Frank Holt” on his way to infamy, committed suicide in jail.

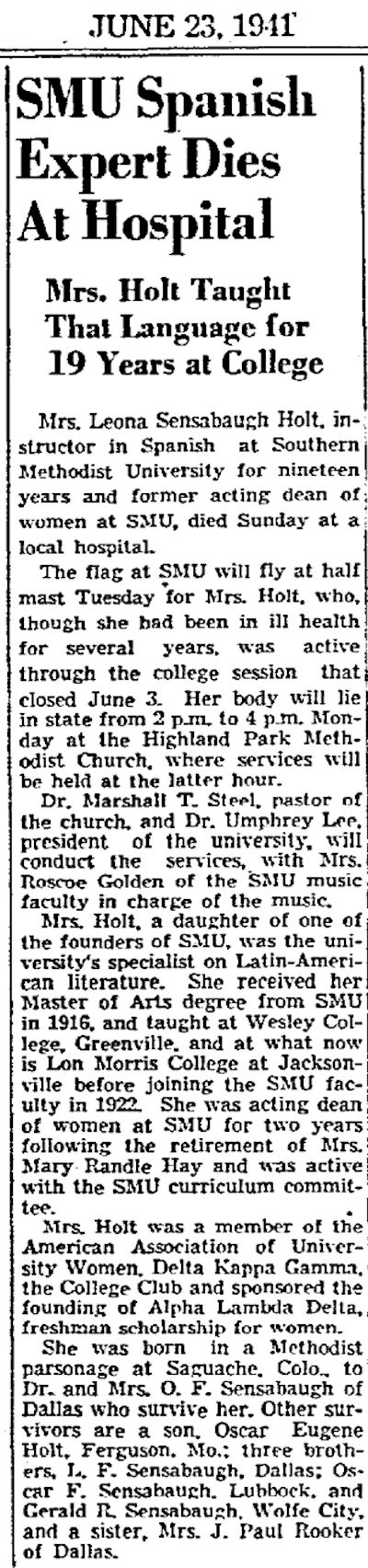

After Holt’s suicide, widow Leona’s academic career somewhat echoed that of her husband: She, not he, joined the faculty of SMU, where she was a professor of Spanish (as Holt had been at Polytechnic) for nineteen years and dean of women for two years. For the rest of her life she would refer to herself as the widow of Frank Holt.

But when Leona Sensabaugh Holt died on June 22, 1941 at age fifty-five, her obituary in the Dallas Morning News did not mention her late husband or his Fourth of July weekend in 1915.

But when Leona Sensabaugh Holt died on June 22, 1941 at age fifty-five, her obituary in the Dallas Morning News did not mention her late husband or his Fourth of July weekend in 1915.

She and her husband are buried in Grove Hill Memorial Park in Dallas.

Sounds like a Hollywood screenplay! Get cracking on that! I’ll line up to buy the first ticket.

Isn’t that a wild one? I stumbled across that chain of events while researching something else not nearly as interesting. That often happens.