Yes, he was a priest. And yes, his Catholic church was Fort Worth’s largest. But there was not a lot of starch in his clerical collar. He liked fast cars and a good game of baseball. And he was not afraid to trade his Bible for a badge and patrol a fringe of Cowtown’s wickedest neighborhood.

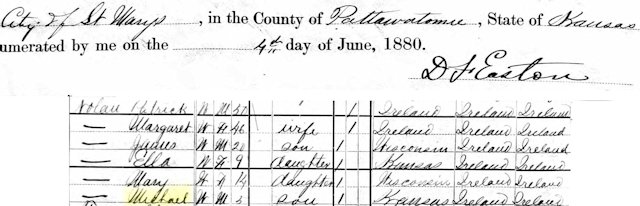

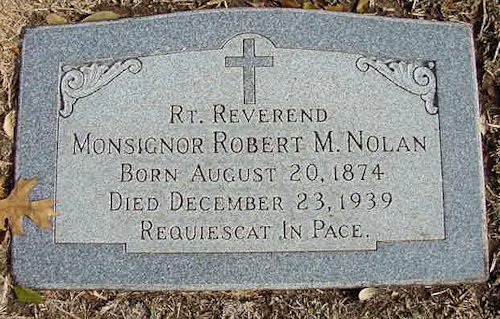

Robert Michael Nolan was born in 1874 in a dugout (a dwelling recessed in the ground and sometimes covered by sod) on a homestead in Kansas. His parents were immigrants from Ireland.

Robert Michael Nolan was born in 1874 in a dugout (a dwelling recessed in the ground and sometimes covered by sod) on a homestead in Kansas. His parents were immigrants from Ireland.

Nolan was drawn to the cloth at an early age. As a boy he would tear a hole in a sheet of newspaper, poke his head through the hole, and wear the sheet as vestments of the church.

In 1892 he graduated from St. Benedict’s College in Atchison, Kansas and then taught Latin, Greek, and English literature at his alma mater for five years. In 1897 he went to St. Joseph’s College in Louisiana, where he received his theology degree. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1898 and assigned to Paris, Texas. He later served in churches in Weatherford and Gainesville.

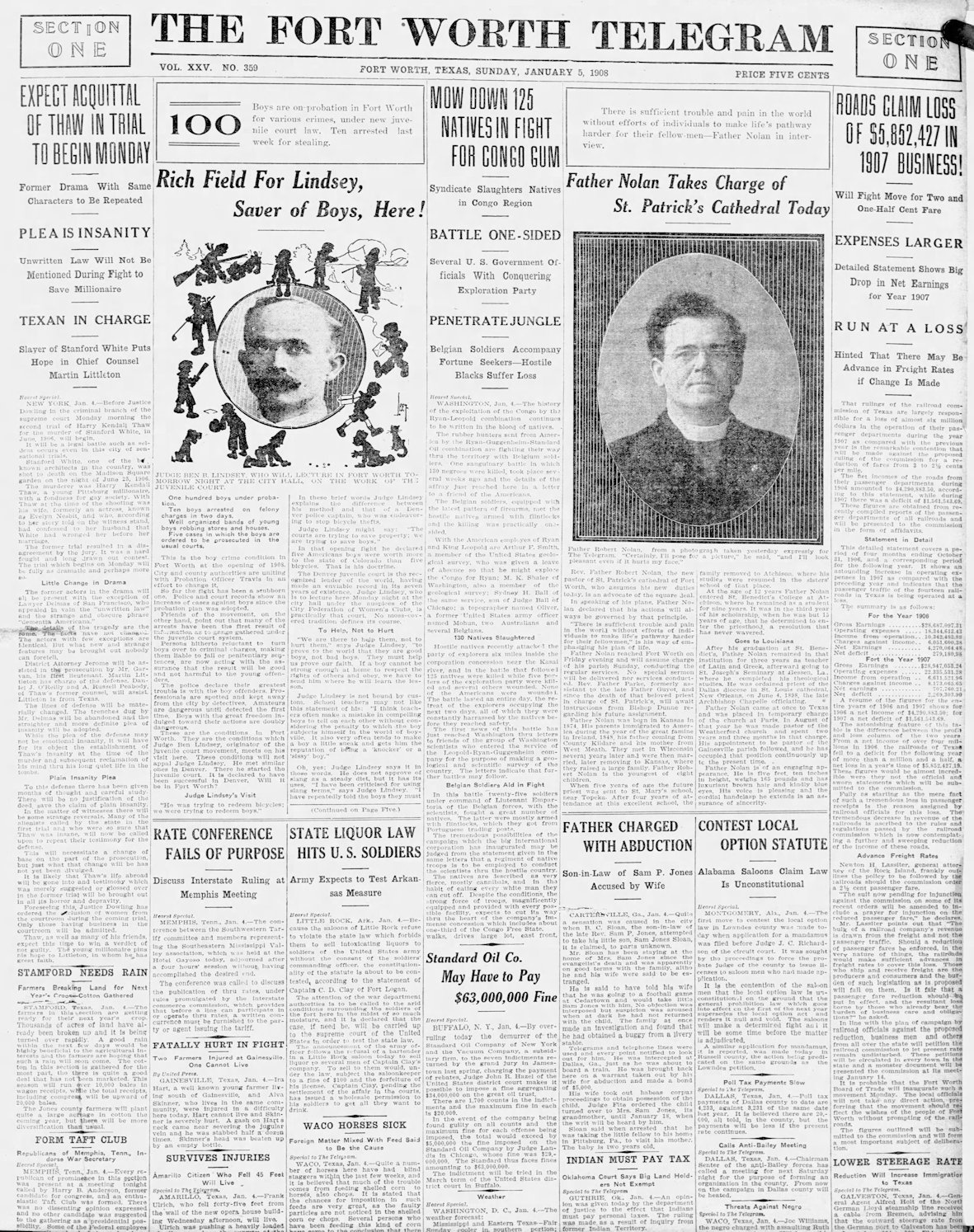

In August 1907 Jean Marie Guyot, pastor of Fort Worth’s St. Patrick Church, died. In January 1908 Father Nolan was appointed to replace Father Guyot.

In August 1907 Jean Marie Guyot, pastor of Fort Worth’s St. Patrick Church, died. In January 1908 Father Nolan was appointed to replace Father Guyot.

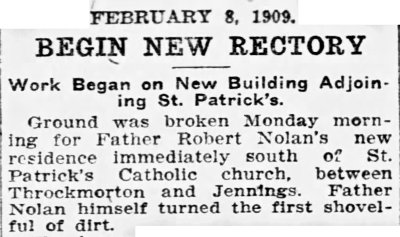

The overarching concern of the clergy, of course, is people. But sometimes the most tangible legacy of the clergy is the buildings in which people worship or learn or live. Father Nolan’s first building project was a new rectory, built in 1909 on the site of the former rectory. A larger rectory was needed as Father Nolan’s church grew because two and sometimes three priests assisted him and lived at the rectory.

The overarching concern of the clergy, of course, is people. But sometimes the most tangible legacy of the clergy is the buildings in which people worship or learn or live. Father Nolan’s first building project was a new rectory, built in 1909 on the site of the former rectory. A larger rectory was needed as Father Nolan’s church grew because two and sometimes three priests assisted him and lived at the rectory.

The rectory, at 1206 Throckmorton Street, is still in use by the church.

During the first two years of Father Nolan’s tenure, three parishes were added: Holy Name southeast of the church, St. Mary of the Assumption south of the church, and St. Rita’s on the East Side.

Father Nolan also would replace the church’s small Stations of the Cross with more exquisite ones and add a 1,268-pipe organ.

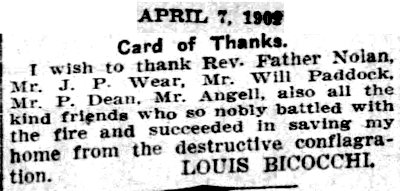

Church leaders are also community leaders. And the best community leaders don’t hesitate to roll up their sleeves in emergencies. When the great South Side fire broke out in 1909 Father Nolan took his horse and buggy to the scene and helped residents remove belongings from their houses. He also climbed onto the roof of the house of pasta prince Louis Bicocchi as it burned and helped keep the fire from spreading.

Church leaders are also community leaders. And the best community leaders don’t hesitate to roll up their sleeves in emergencies. When the great South Side fire broke out in 1909 Father Nolan took his horse and buggy to the scene and helped residents remove belongings from their houses. He also climbed onto the roof of the house of pasta prince Louis Bicocchi as it burned and helped keep the fire from spreading.

As few days later, the Star-Telegram reported, at the recommendation of Police Chief James Maddox, Fire and Police Commissioner George Mulkey appointed Nolan a special officer. As a special officer Nolan wore a badge and carried a pistol as he patrolled the neighborhood of the church after it had been “infested” by a “gang of tramps.”

As few days later, the Star-Telegram reported, at the recommendation of Police Chief James Maddox, Fire and Police Commissioner George Mulkey appointed Nolan a special officer. As a special officer Nolan wore a badge and carried a pistol as he patrolled the neighborhood of the church after it had been “infested” by a “gang of tramps.”

The church was located on the western fringe of the vice district Hell’s Half-Acre.

The Star-Telegram in 2002 wrote: “Watching the flurry of vice from across Throckmorton Street was Rev. Robert M. Nolan, who didn’t want the wicked wrongdoings to spill onto the steps of St. Patrick Cathedral. . . . Nolan’s beat was the streets contiguous to St. Patrick . . . It’s not recorded whether his badge or his Bible had the greatest effect on the denizens of the Acre who encountered Nolan, who was more than six feet tall and played college football. But the area around the Roman Catholic church was said to have the lowest crime rate in Hell’s Half-Acre.”

The Star-Telegram wrote that a brothel was located across Throckmorton Street from the church. Nolan would cross the great divide to counsel prostitutes, some of whom began attending the church and became regulars in the confessional booth.

The Star-Telegram wrote that during the 1920s Father Nolan teamed up with J. Frank Norris of First Baptist Church in a campaign to clean up the Acre. Politics makes strange pewfellows: Norris was anti-Catholic and sympathetic to the Ku Klux Klan, which persecuted African Americans and Catholics.

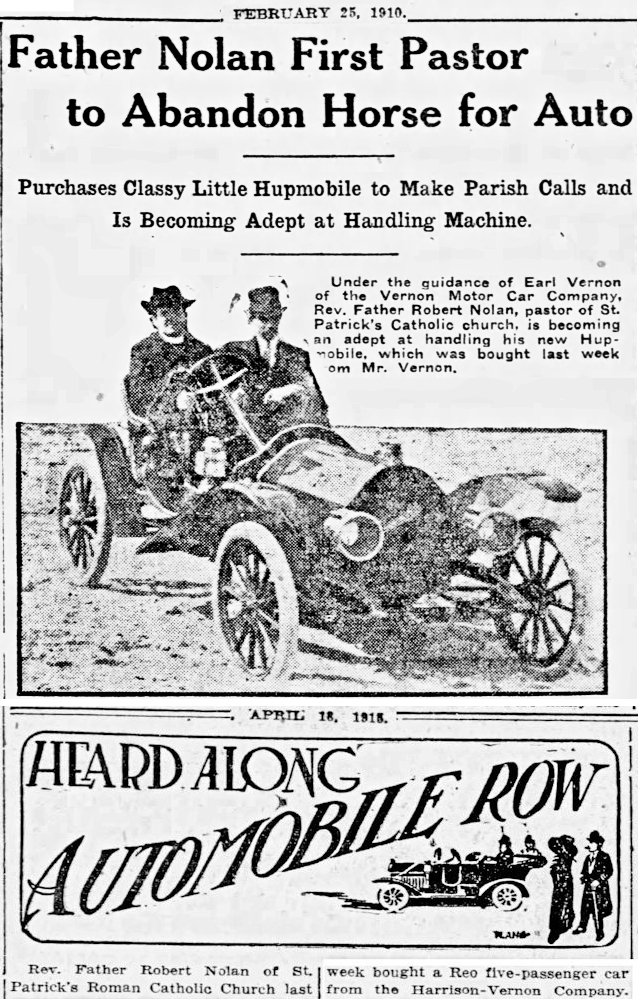

Father Nolan had two secular passions. One was automobiles. In 1910 Father Nolan became the first pastor in town to own an automobile: a Hupmobile. Automobiles were still relatively rare in Fort Worth in 1910, when Fort Worth had a population of 73,312 but only 959 registered automobiles.

Father Nolan had two secular passions. One was automobiles. In 1910 Father Nolan became the first pastor in town to own an automobile: a Hupmobile. Automobiles were still relatively rare in Fort Worth in 1910, when Fort Worth had a population of 73,312 but only 959 registered automobiles.

Five years later, in April 1915 Father Nolan bought a five-passenger Reo.

There may not have been many other cars in Fort Worth, but on April 16, 1915, Father Nolan found one of them—head on. Soon after buying his Reo, Father Nolan, with two other priests as passengers, collided with another car on the Dallas Pike (Lancaster Avenue) near Tandy Lake.

There may not have been many other cars in Fort Worth, but on April 16, 1915, Father Nolan found one of them—head on. Soon after buying his Reo, Father Nolan, with two other priests as passengers, collided with another car on the Dallas Pike (Lancaster Avenue) near Tandy Lake.

Father Nolan had a reputation as a leadfoot, and the community was said to have been relieved when he gave up driving.

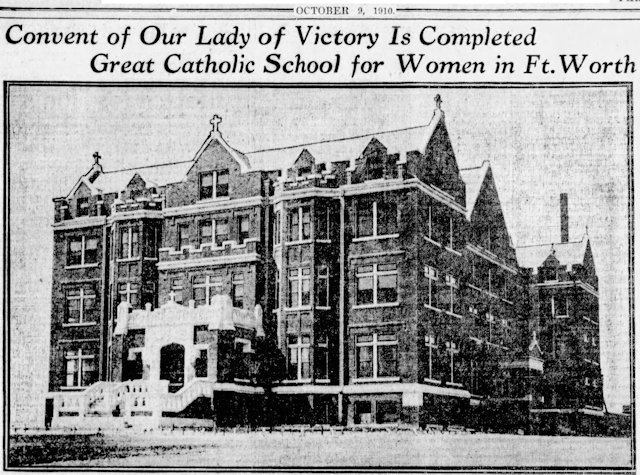

In 1909 Father Nolan embarked on another building project with the Sisters of St. Mary of Namur, who operated St. Ignatius Academy next to the church. The sisters bought fifteen acres of Shaw brothers dairy land on Hemphill Street on the southern edge of town and built Our Lady of Victory Academy.

In 1909 Father Nolan embarked on another building project with the Sisters of St. Mary of Namur, who operated St. Ignatius Academy next to the church. The sisters bought fifteen acres of Shaw brothers dairy land on Hemphill Street on the southern edge of town and built Our Lady of Victory Academy.

The building today houses Victory Arts Center.

The building today houses Victory Arts Center.

Father Nolan’s other secular passion was baseball. Years later Wheeler Worley, who had known Father Nolan when Nolan was a young priest in Gainesville, recalled: “I was just a youngster, but I remember him riding his horse down to the city park where we played baseball. He would bring his own glove, take off his coat and collar, and play ball with us. And he was a good player, too. The boys loved him for it.”

Father Nolan’s other secular passion was baseball. Years later Wheeler Worley, who had known Father Nolan when Nolan was a young priest in Gainesville, recalled: “I was just a youngster, but I remember him riding his horse down to the city park where we played baseball. He would bring his own glove, take off his coat and collar, and play ball with us. And he was a good player, too. The boys loved him for it.”

In 1910 Father Nolan was the star of a game played at Lake Erie trolley park between the Knights of Columbus lodges of Fort Worth and Dallas. (Knights of Columbus is a Catholic fraternal service order.) Fort Worth Fire Chief W. E. Bideker played first base.

Fast-forward ten years. In 1920 when the Fort Worth Panthers won the Texas League championship and the first Dixie Series, Nolan accompanied the team by train to Little Rock for the final game and acted as chaperone. He even got to sit in the dugout during the game.

Later at a banquet honoring the team Nolan said: “All my life I’ve been curious to sit on a bench with professional ball players and travel with them. I’ve always liked to study everything possible, and I thought perhaps I might hear a new ‘cuss’ word, but I must say I didn’t—not from the Fort Worth ball players. I’m not only proud of what they’ve done to win the pennant, but I’m proud to have mingled with them and to know them.”

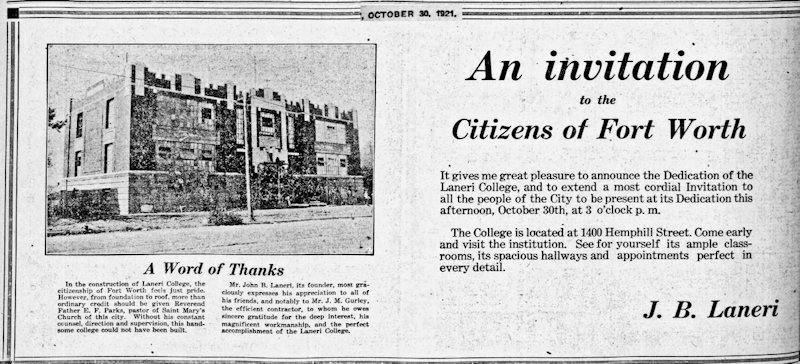

In 1921 Father Nolan worked with other local Catholic leaders in another educational project as Fort Worth’s other pasta prince, John B. Laneri, built Laneri College in memory of his wife. The “college” actually taught only grades five through high school. And was for boys only. The building also housed a Knights of Columbus evening school.

In 1921 Father Nolan worked with other local Catholic leaders in another educational project as Fort Worth’s other pasta prince, John B. Laneri, built Laneri College in memory of his wife. The “college” actually taught only grades five through high school. And was for boys only. The building also housed a Knights of Columbus evening school.

The building, at 1400 Hemphill Street, today houses Cassata Catholic High School, named for Joseph J. Cassata, who was appointed bishop of the Fort Worth diocese when the diocese was created in 1969.

The building, at 1400 Hemphill Street, today houses Cassata Catholic High School, named for Joseph J. Cassata, who was appointed bishop of the Fort Worth diocese when the diocese was created in 1969.

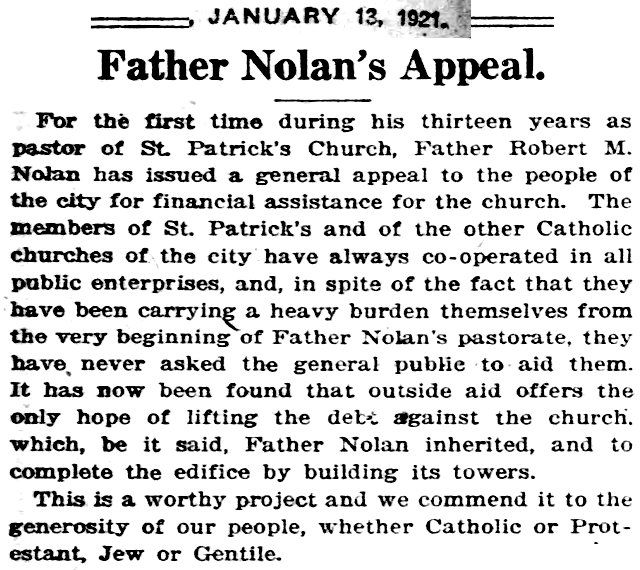

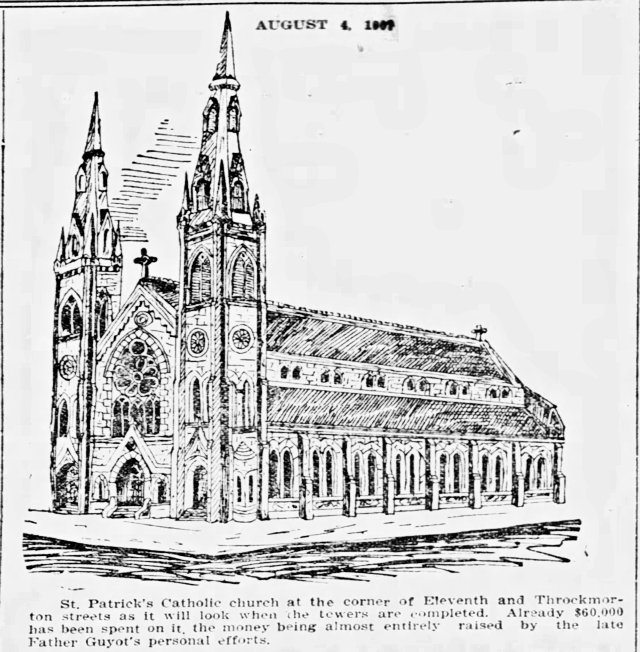

Also in 1921 Father Nolan appealed for donations so that St. Patrick Church could finally finish the building’s two towers. The church building had been dedicated in 1892, but the financial panic of 1893 prevented the congregation from building the spires atop the tower bases. The tower bases are barely taller than the top of the rose window on the front of the building. The 1907 sketch shows how the spires would look when finished.

Also in 1921 Father Nolan appealed for donations so that St. Patrick Church could finally finish the building’s two towers. The church building had been dedicated in 1892, but the financial panic of 1893 prevented the congregation from building the spires atop the tower bases. The tower bases are barely taller than the top of the rose window on the front of the building. The 1907 sketch shows how the spires would look when finished.

They were never built.

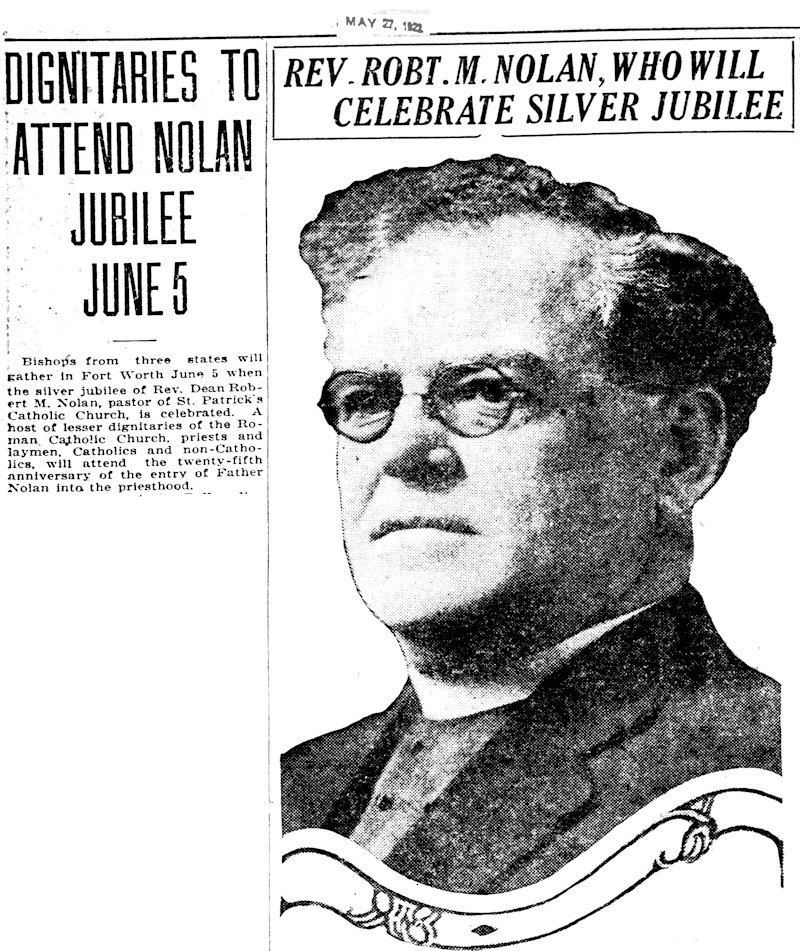

In 1923 Father Nolan was honored for twenty-five years in the priesthood.

In 1923 Father Nolan was honored for twenty-five years in the priesthood.

Two years later he was elevated to the title of “monsignor” but remained pastor of St. Patrick.

Two years later he was elevated to the title of “monsignor” but remained pastor of St. Patrick.

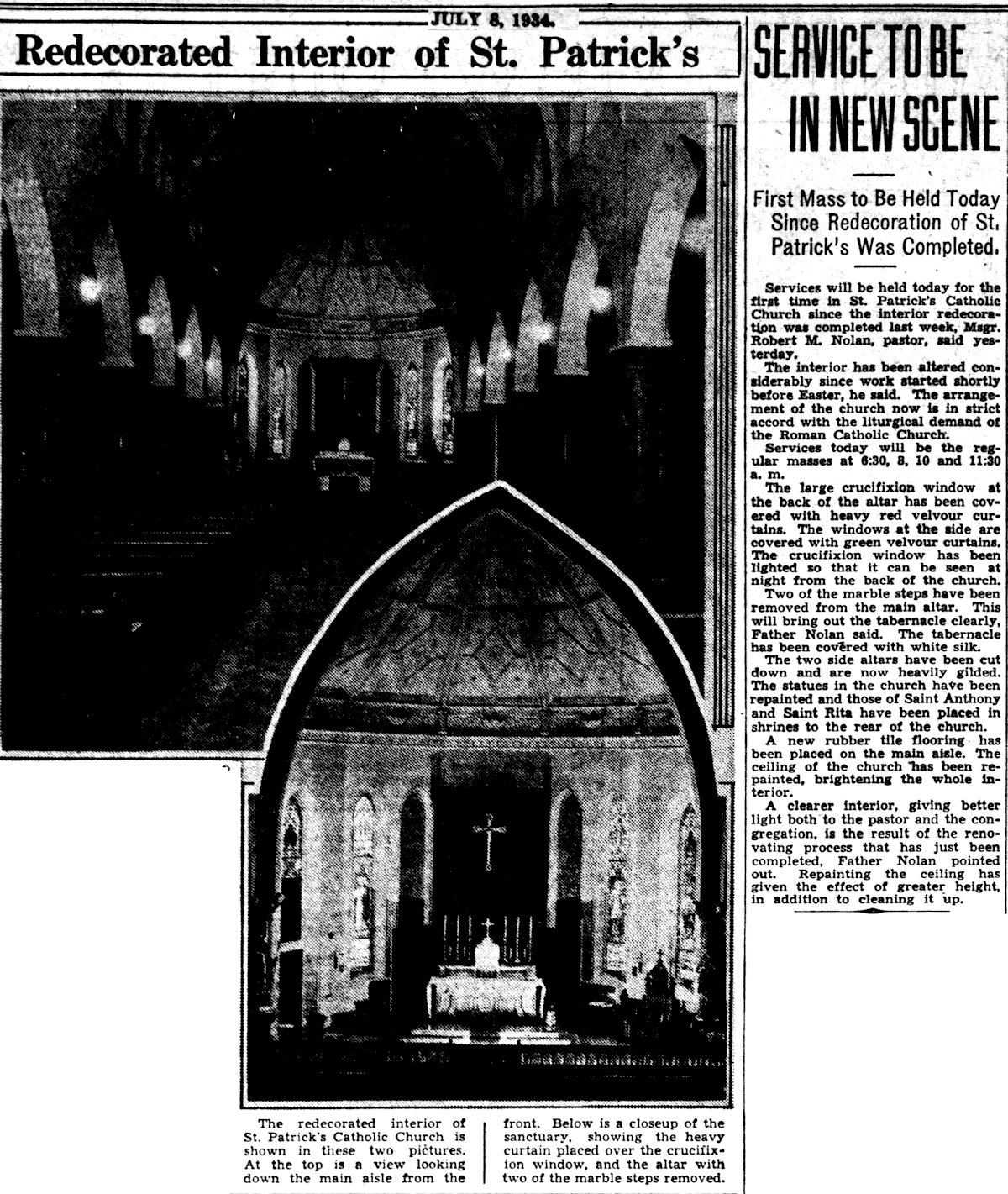

In 1934 Nolan oversaw one of his final building projects: redecoration of the church interior.

In 1934 Nolan oversaw one of his final building projects: redecoration of the church interior.

The church today.

The church today.

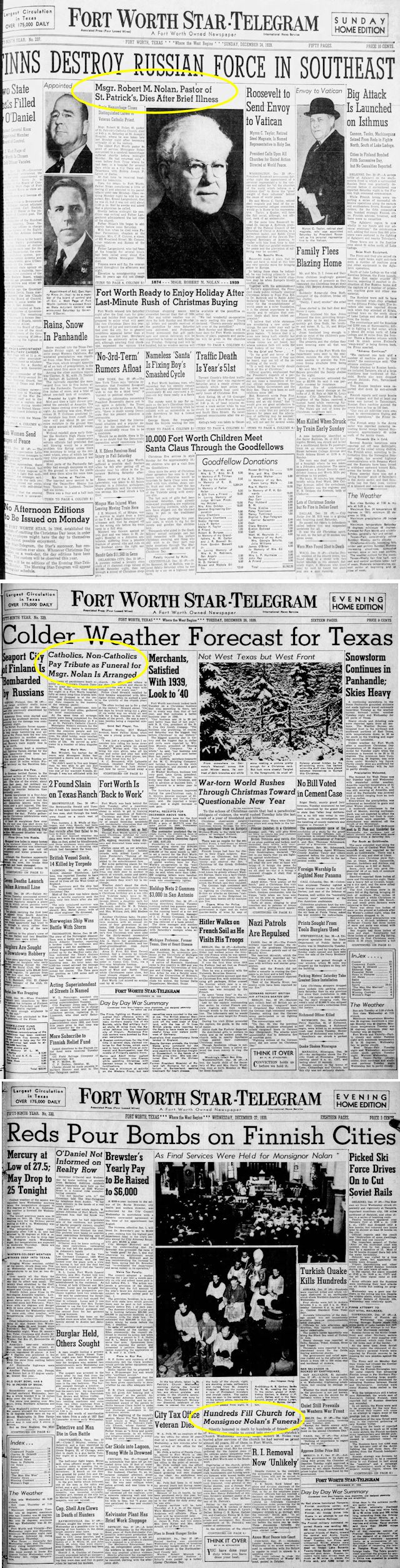

Five years later, on December 23, 1939, as Nolan was preparing to celebrate his fortieth Christmas since becoming a priest, he died at age sixty-five.

Five years later, on December 23, 1939, as Nolan was preparing to celebrate his fortieth Christmas since becoming a priest, he died at age sixty-five.

His death was mourned by people of all denominations. At his funeral were a pew of Protestant ministers and a pew of Jewish rabbis.

Very Reverend Wendelin Nold of Dallas, who once had served Monsignor Nolan as altar boy, preached the funeral sermon.

Nold said: “The sorrow felt because of Father Nolan’s death sweeps out beyond the limits of the parish, beyond the confines of race and creed. The parish has lost a pastor; the diocese a leader, and the people a friend. All are constrained by a common woe for Father Nolan, pastor, priest, and friend.

“These three characters of pastor, priest, and friend he had in a superlative degree of excellence. He was beloved by God.

“And in addition to the common feeling held by his lay friends, Father Nolan won the signal recognition of his superiors by his zeal. In Father Nolan there was no tint of sanctimoniousness, and because of this he was honored by Catholic, non-Catholic, high, low, rich, and poor alike. Because he was loved in life, now his memory is in benediction.”

St. Patrick Church congregant A. C. Broussard recalled that Nolan had a “weakness for hard luck stories” and never turned away a beggar or anyone else with a tale of woe: “He gave away all the money that came his way and often was surprised to find that his grocery bill had jumped to as much as $150 because of his liberality with hungry bums who fairly haunted the steps of the rectory. He led a long and successful fight to keep the downtown [church] property, too. There were many times when it would have been lost except for his determined efforts. Several times he resigned as a means of stirring up the parishioners so they would get busy and raise the necessary money.”

William R. Hoover, author of St. Patrick: The First 100 Years, described Nolan as “an open, outgoing man, determined and aggressive with a sense of humor and a tendency to look to the future rather than to the past.”

Fourteen years in the future, in 1953 Nolan’s church was elevated to the status of co-cathedral. In 1969—thirty years after his death—it was elevated to the status of cathedral.

Monsignor Robert Michael Nolan is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Monsignor Robert Michael Nolan is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

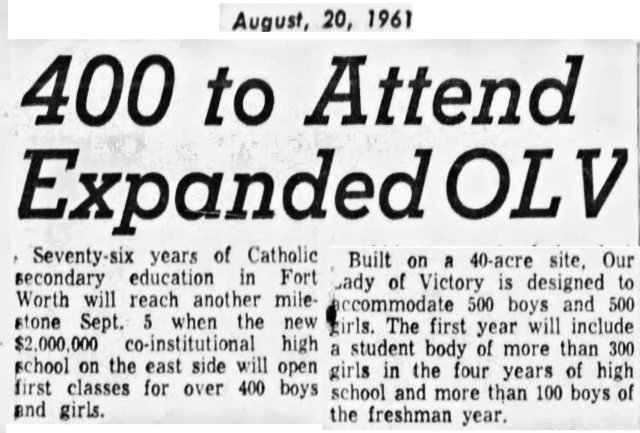

In 1961 a new Our Lady of Victory High School opened just north of the turnpike on the East Side.

In 1961 a new Our Lady of Victory High School opened just north of the turnpike on the East Side.

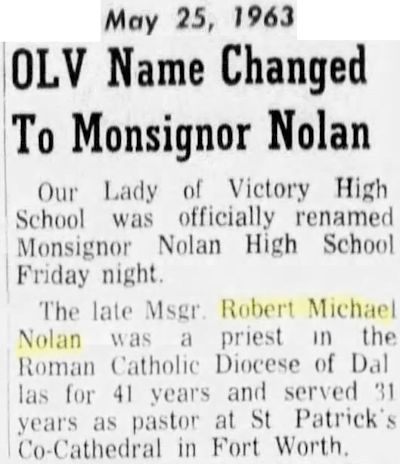

In 1963 Our Lady of Victory High School was renamed for Monsignor Nolan.

In 1963 Our Lady of Victory High School was renamed for Monsignor Nolan.

(Thanks to Fort Worth historian Donna Humphrey Donnell for her help.)

Wonderful!!

Thank you. A remarkable figure in Fort Worth history.