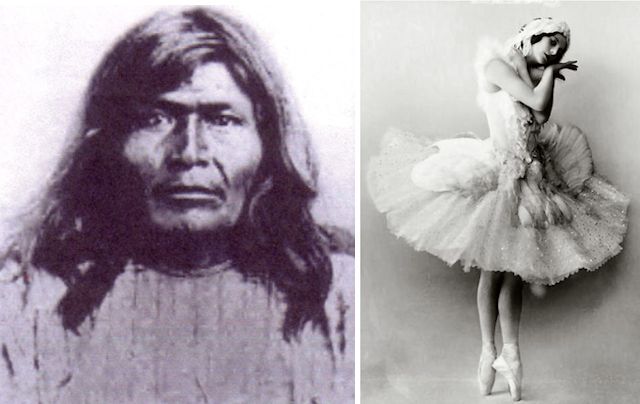

Below are photos of two historical figures:

On the left is Victorio (1825-1880), an Apache chief who led a guerrilla war against the United States and Mexico in the nineteenth century. On the right is Anna Pavlova (1881-1931) of Russia, who was one of the greatest classical ballerinas in history.

On the left is Victorio (1825-1880), an Apache chief who led a guerrilla war against the United States and Mexico in the nineteenth century. On the right is Anna Pavlova (1881-1931) of Russia, who was one of the greatest classical ballerinas in history.

What connections could these two people have to each other and to Fort Worth history?

Our first connection is . . .

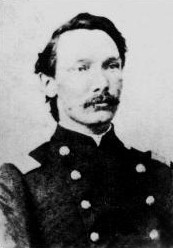

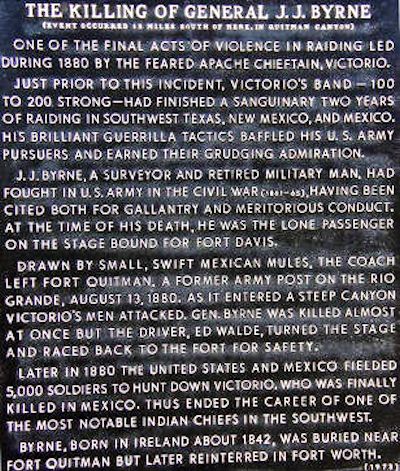

J. J. Byrne. Byrne was born in Ireland in 1842 and immigrated to New York as a child. As a Union soldier during the Civil War he was noted for his gallantry. On March 13, 1865 he was breveted to the rank of brigadier general for his conduct at the battles of Campti and Pleasant Hill and to the rank of major general for his conduct at the battles of Yellow Bayou and Moore’s Plantation. He was, the Fort Worth Democrat claimed, the youngest general in the Union army.

J. J. Byrne. Byrne was born in Ireland in 1842 and immigrated to New York as a child. As a Union soldier during the Civil War he was noted for his gallantry. On March 13, 1865 he was breveted to the rank of brigadier general for his conduct at the battles of Campti and Pleasant Hill and to the rank of major general for his conduct at the battles of Yellow Bayou and Moore’s Plantation. He was, the Fort Worth Democrat claimed, the youngest general in the Union army.

Byrne was mustered out on May 31, 1866 at Victoria, Texas. After the war Byrne was appointed U.S. marshal for the eastern district of Texas. He also was spoken of as a candidate for Congress. Clip is from the 1868 Dallas Herald.

Byrne was mustered out on May 31, 1866 at Victoria, Texas. After the war Byrne was appointed U.S. marshal for the eastern district of Texas. He also was spoken of as a candidate for Congress. Clip is from the 1868 Dallas Herald.

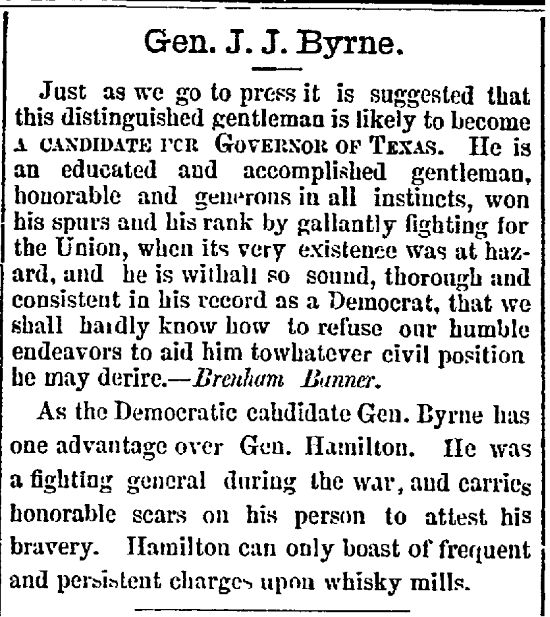

A year later Bryne again was mentioned as a possible political candidate. Clip is from the August 19, 1869 Houston Daily Union.

A year later Bryne again was mentioned as a possible political candidate. Clip is from the August 19, 1869 Houston Daily Union.

Byrne settled in Fort Worth and became a land agent and surveyor for the Texas & Pacific railway. Clip is from the 1877 city directory.

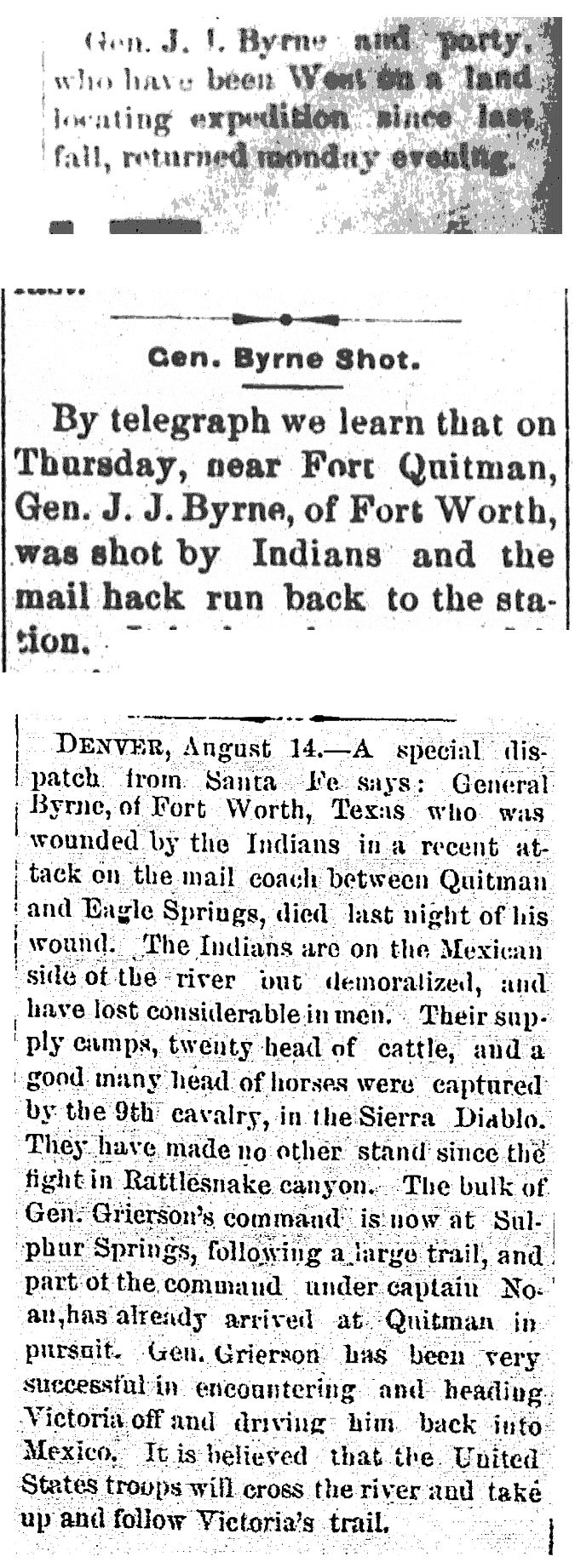

In 1880 Byrne was surveying land given to the railroad by the state of Texas as the T&P laid track west of Fort Worth toward El Paso. On a night in August Byrne sat in a shack near the mission of Ysleta (in present-day El Paso). He was all too aware of recent attacks on white settlers in the area by Apache chief Victorio. In fact, Byrne had just had a dire premonition.

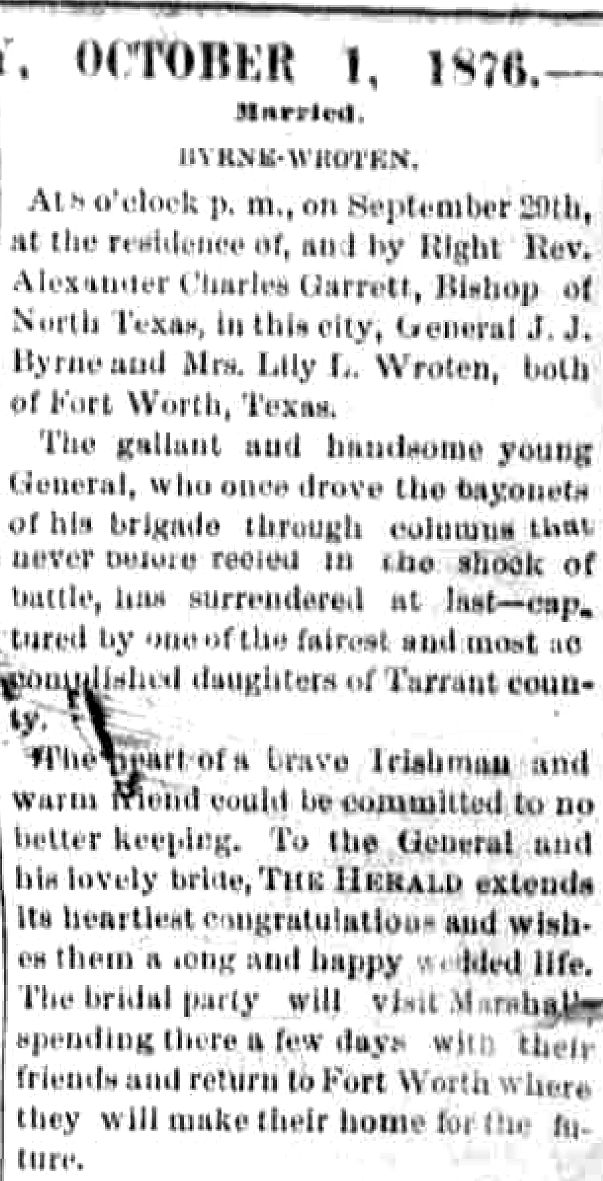

That premonition brings us to our second connection. In 1876 General Byrne had married Lilly Loving Wroten of Fort Worth. Clip is from the Dallas Herald. That night in August 1880 in Ysleta General Byrne wrote to his wife of four years, alluding to his premonition: “I have made all my plans and I cannot change them with honor to myself but I feel that I shall never see my darling wife again,” he wrote, “and that this will be my final good-bye. . . . If you determine to form another earthly tie, I only ask and, dying, pray that you will counsel your best judgment to enable you to make a choice in all things worthy of you.”

Byrne also intended for his letter to serve as his will, appointing his widow sole executrix of his estate, including sections of land in west Texas.

Byrne addressed the letter to his wife with instructions that it be delivered to her only in the event of his death.

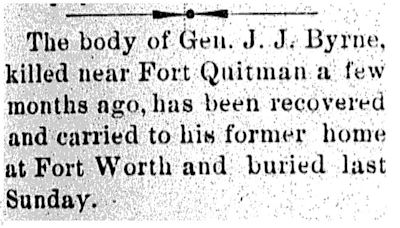

There are times when you hate to be right. A few days later, on August 13, 1880, Byrne’s premonition came true. Byrne was the only passenger on a mule-drawn stagecoach traveling from Fort Quitman (eighty miles below El Paso) to Fort Davis. Nine miles out the stage was attacked by Victorio’s band of warriors. General Byrne was shot in the hip and back. The stagecoach driver, Ed Walde, turned the stage around and raced back to the fort, but Byrne soon died.

Two months after General Byrne was killed, Mexico’s Colonel Terraza and his troops attacked Victorio’s camp in Mexico. Victorio was killed.

General J. J. Byrne, like General Edward H. Tarrant and Major Ripley Arnold, originally was buried elsewhere but was reburied in Pioneers Rest Cemetery. The monument was erected by General Byrne’s widow Lilly.

General J. J. Byrne, like General Edward H. Tarrant and Major Ripley Arnold, originally was buried elsewhere but was reburied in Pioneers Rest Cemetery. The monument was erected by General Byrne’s widow Lilly.

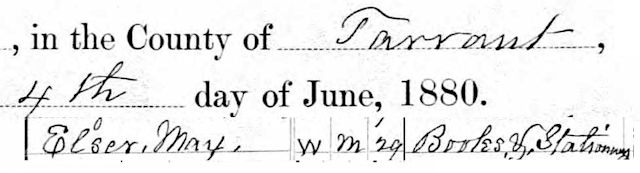

Fast-forward three years. In 1883 J. J. Byrne’s widow Lilly did indeed “form another earthly tie” when she married our third connection: Max Elser. Max Elser was ubiquitous in early Fort Worth. He opened the town’s first telegraph company in 1874 and sent the town’s first telegraph.

Fast-forward three years. In 1883 J. J. Byrne’s widow Lilly did indeed “form another earthly tie” when she married our third connection: Max Elser. Max Elser was ubiquitous in early Fort Worth. He opened the town’s first telegraph company in 1874 and sent the town’s first telegraph.

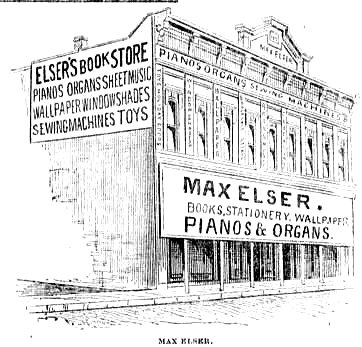

Max Elser owned a bookstore. He was city treasurer, an alderman, a director of City National Bank and Fort Worth & Denver City railroad. He also mined for coal and drilled for oil in central west Texas.

Max Elser owned a bookstore. He was city treasurer, an alderman, a director of City National Bank and Fort Worth & Denver City railroad. He also mined for coal and drilled for oil in central west Texas.

Max Elser’s store was one of the few places where you could buy a piano or organ in the nineteenth century.

Max Elser’s store was one of the few places where you could buy a piano or organ in the nineteenth century.

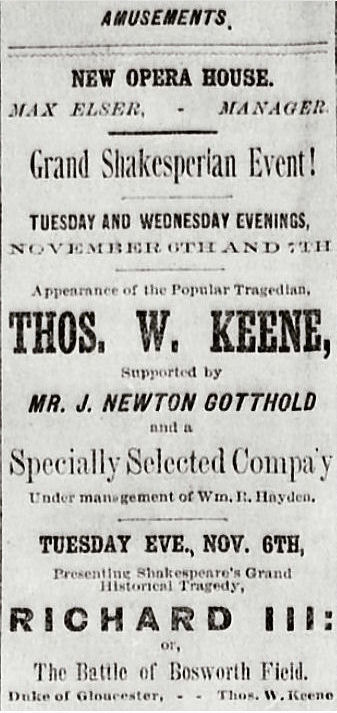

And in 1883 Max Elser was manager of Fort Worth’s new opera house at 3rd and Rusk (now Commerce) streets.

And in 1883 Max Elser was manager of Fort Worth’s new opera house at 3rd and Rusk (now Commerce) streets.

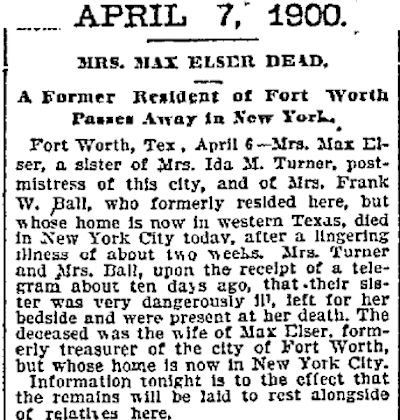

Lilly Elser died in 1900.

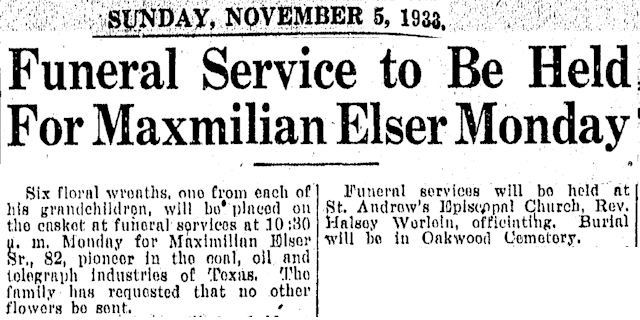

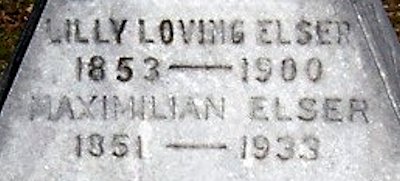

Max Elser died in 1933. Lilly and Max are buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

Max Elser died in 1933. Lilly and Max are buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

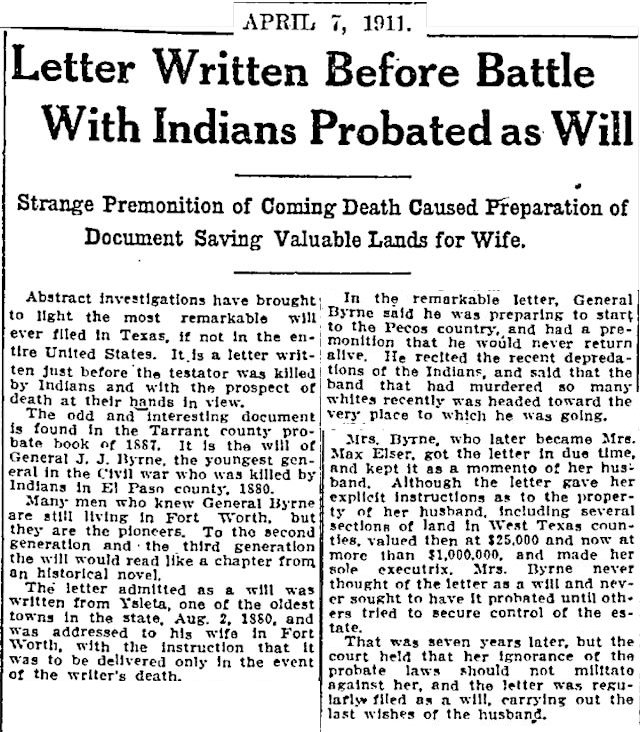

Now let’s back up. In 1911 the Star-Telegram wrote that in 1887—seven years after General J. J. Byrne was killed and four years after his widow married Max Elser—the letter that Byrne had written to his wife on that night in west Texas in August 1880 was indeed probated as his will, giving his widow control of land valued in 1911 at $1 million.

Now let’s back up. In 1911 the Star-Telegram wrote that in 1887—seven years after General J. J. Byrne was killed and four years after his widow married Max Elser—the letter that Byrne had written to his wife on that night in west Texas in August 1880 was indeed probated as his will, giving his widow control of land valued in 1911 at $1 million.

Max Elser and the widow of General J. J. Byrne had two sons. Both of them became journalists.

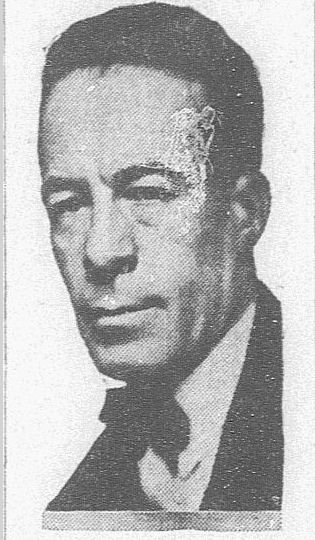

Frank Elser (1885-1935) worked at the Fort Worth Telegram, then went on to Associated Press in New York and London. When General Pershing chased Pancho Villa in 1916-1917, Elser went along for the New York Times. Later he wrote for national magazines and adapted novels, such as The Farmer Takes a Wife, for the stage. His own novel, Keen Desire, published in 1926, was a thinly veiled depiction of socially stratified Fort Worth.

Frank Elser (1885-1935) worked at the Fort Worth Telegram, then went on to Associated Press in New York and London. When General Pershing chased Pancho Villa in 1916-1917, Elser went along for the New York Times. Later he wrote for national magazines and adapted novels, such as The Farmer Takes a Wife, for the stage. His own novel, Keen Desire, published in 1926, was a thinly veiled depiction of socially stratified Fort Worth.

Playwright Eugene O’Neill called the novel “genuinely fine.” The New Republic magazine called it “highly original and exciting.”

Other reviewers used other terms: “obscene,” “unnecessary,” “unforgivable.”

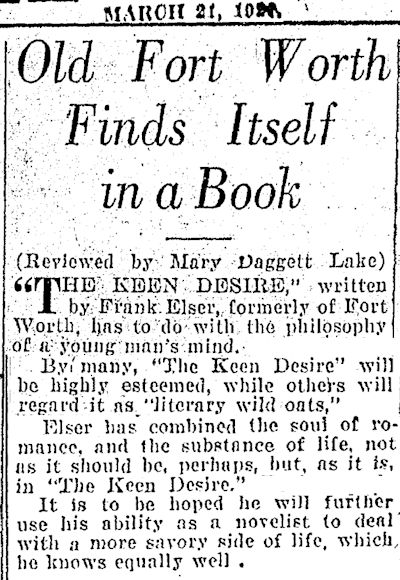

Fort Worth historian Mary Daggett Lake was measured in her review: “It is to be hoped he [Elser] will further use his ability as a novelist to deal with a more savory side of life . . .”

Fort Worth historian Mary Daggett Lake was measured in her review: “It is to be hoped he [Elser] will further use his ability as a novelist to deal with a more savory side of life . . .”

The book was “not welcome” at the Fort Worth library, even though the librarian was Frank Elser’s aunt. The book also was banned in Elser’s then-hometown of Cranford, New Jersey.

Our fourth and last connection was the other son of Lilly and Max Elser: Max Elser Jr. (1889-1961). Like brother Frank, Max Jr. worked at the Fort Worth Telegram and then went to New York, where he worked on the Evening Sun. He wrote and produced plays on Broadway. He formed a newspaper features service that syndicated the “Tarzan” comic strip.

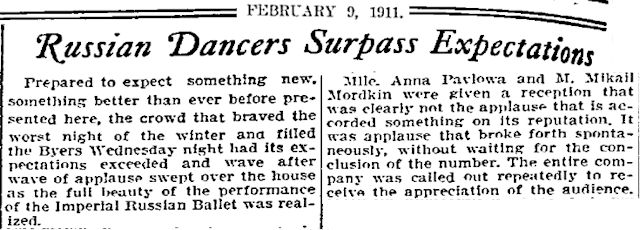

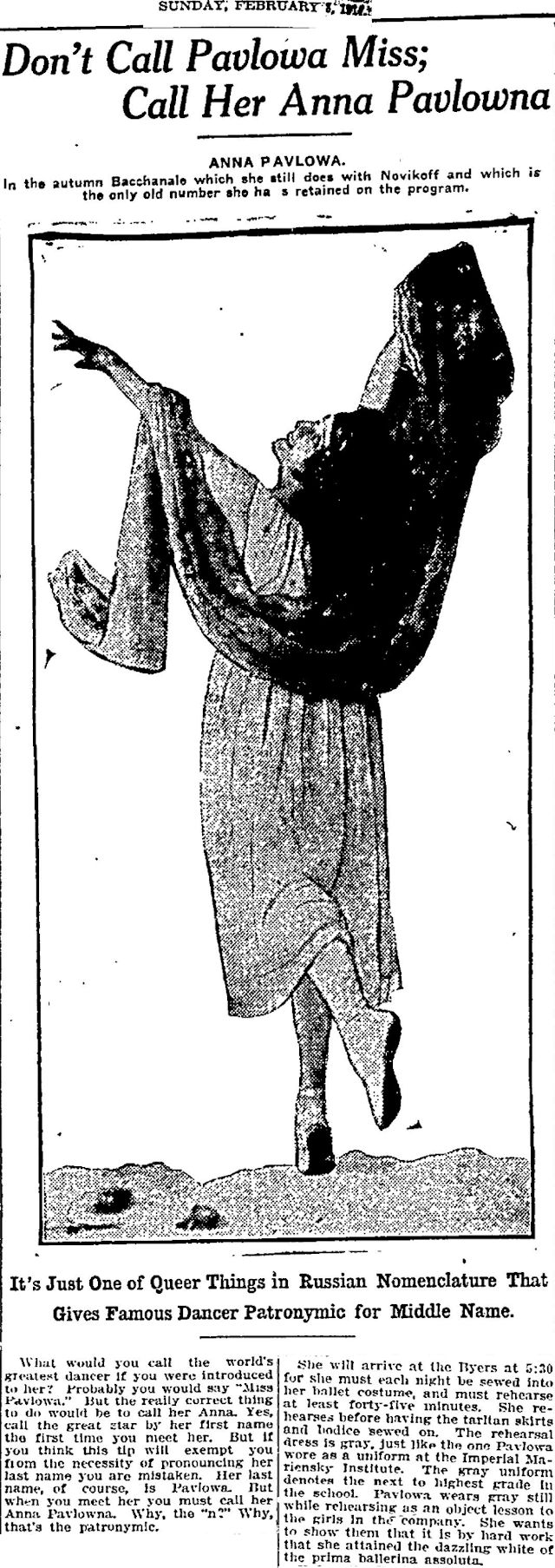

Max Elser Jr. drifted into public relations work and in 1911 became press agent for . . . Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova. Pavlova performed in Fort Worth that year at the Byers Opera House at 7th and Rusk streets.

Max Elser Jr. drifted into public relations work and in 1911 became press agent for . . . Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova. Pavlova performed in Fort Worth that year at the Byers Opera House at 7th and Rusk streets.

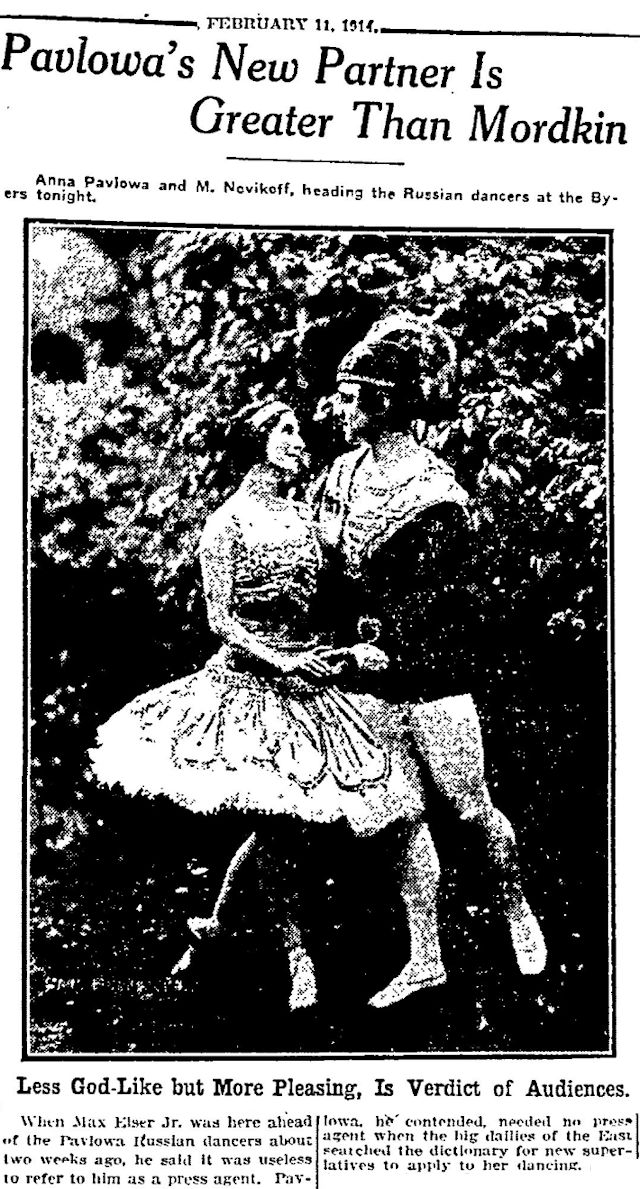

In 1914 when Anna Pavlova made her first world tour, Max Elser Jr. traveled ahead of her to the towns, including Fort Worth, where she would perform. In February 1914 Pavlova again performed at Byers Opera House.

In 1914 when Anna Pavlova made her first world tour, Max Elser Jr. traveled ahead of her to the towns, including Fort Worth, where she would perform. In February 1914 Pavlova again performed at Byers Opera House.

When the Pavlova tour came to Fort Worth, Elser jokingly complained to the Star-Telegram that he had little to do because newspaper critics had usurped his job with their superlatives for Pavlova’s dancing: “divinity,” “soul,” “rhapsody,” “full wine cup of living.”

Max Elser Jr. had no trouble getting Anna Pavlova a lot of publicity in his old hometown:

Byers Opera House presented two productions that week in February 1914: Anna Pavlova and Blue Bird. Pavlova performed one performance only. Notice the signature by artist Plang in the upper left.

Byers Opera House presented two productions that week in February 1914: Anna Pavlova and Blue Bird. Pavlova performed one performance only. Notice the signature by artist Plang in the upper left.

The Star-Telegram reported that Anna Pavlova stayed at the Westbrook Hotel, where she ate borscht—”and nothing else”—for dinner.

The Star-Telegram reported that Anna Pavlova stayed at the Westbrook Hotel, where she ate borscht—”and nothing else”—for dinner.

The Star-Telegram reported that the audience was “moderate” on February 11 but that Byers manager Phil Greenwall had announced that Pavlova would return on February 26.

The Star-Telegram reported that the audience was “moderate” on February 11 but that Byers manager Phil Greenwall had announced that Pavlova would return on February 26.

Anna Pavlova indeed gave Max Elser Jr.’s hometown a second performance on February 26 at Byers Opera House, the opera house that had replaced the opera house that Max Sr. had managed thirty years earlier.

Anna Pavlova indeed gave Max Elser Jr.’s hometown a second performance on February 26 at Byers Opera House, the opera house that had replaced the opera house that Max Sr. had managed thirty years earlier.

Anna Pavlova died in 1931.

See her dance in 1907—twenty-seven years after General J. J. Byrne had a premonition and Apache chief Victorio attacked a stagecoach in the wilds of west Texas:

George Armstrong Custer was promoted to General at age 23. Three days before Gettysburg. However, I think Byrne still beat him because he was actually born in 1842 (rather than 1841) and promoted to General in March 1865. While they were maybe both 23 when promoted, I think Byrne was promoted sooner after his birthday. And he MIGHT have only been 22.

Odd as well that Custer died at 36 and Byrne at 38.

Steve, that “youngest general” label comes from the Handbook of Texas, which quotes a Fort Worth newspaper of the 1800s. The handbook does not even give a year of birth for Byrne, so there certainly is room for debate. I have added attribution for the label. Thanks for the heads-up.