They were the sons of one of Fort Worth’s pioneers: William Bonaparte (“Bony”) Tucker. Tucker was Tarrant County’s third sheriff (1856-1858), among the founders of Fort Worth’s first Masonic lodge, served as county judge and district clerk.

Son Rowan was born in 1855 north of Fort Worth in what today is the Diamond Hill-Jarvis neighborhood. He was among the first white children born in this area after the Army abandoned the fort in 1853.

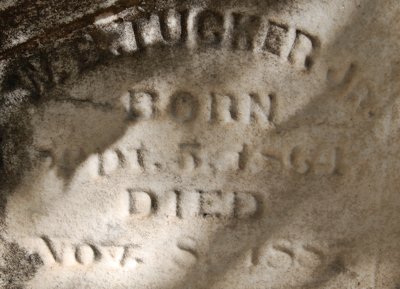

Son William Bonaparte Jr. (also called “Bony”) was born in 1861.

Son Rowan’s life would be long. Son Bony’s life would be short—ended by a bad decision that allowed no do-over.

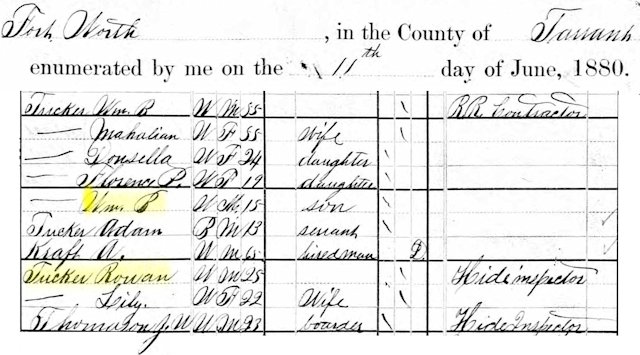

About 1870 the Tucker family moved from north of town to south of town, where Bony Sr. built the first house. In 1880 Bony Jr., still a student, lived with Bony Sr. in the Tucker family house on the 160-acre homestead. Rowan, a hide inspector, lived close by on the homestead. The homestead, located at today’s South Main and Tucker streets, became known as “Tucker’s Hill.” Bony Sr. platted part of his homestead and sold lots, becoming the first developer of the area. Today he is remembered as the “father of the South Side.”

About 1870 the Tucker family moved from north of town to south of town, where Bony Sr. built the first house. In 1880 Bony Jr., still a student, lived with Bony Sr. in the Tucker family house on the 160-acre homestead. Rowan, a hide inspector, lived close by on the homestead. The homestead, located at today’s South Main and Tucker streets, became known as “Tucker’s Hill.” Bony Sr. platted part of his homestead and sold lots, becoming the first developer of the area. Today he is remembered as the “father of the South Side.”

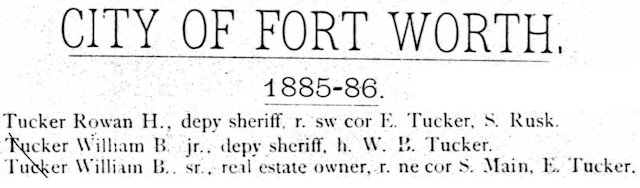

In 1878 son Rowan became a deputy sheriff. By 1885 the lives of brothers Rowan and Bony Jr. were running parallel: Both were deputy sheriffs.

In 1878 son Rowan became a deputy sheriff. By 1885 the lives of brothers Rowan and Bony Jr. were running parallel: Both were deputy sheriffs.

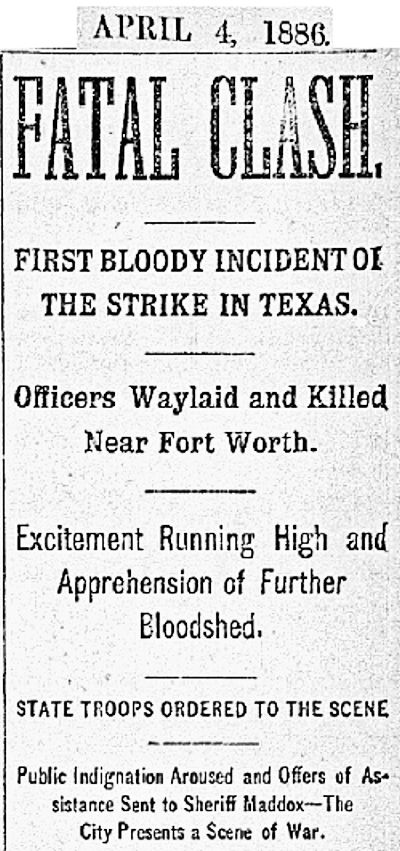

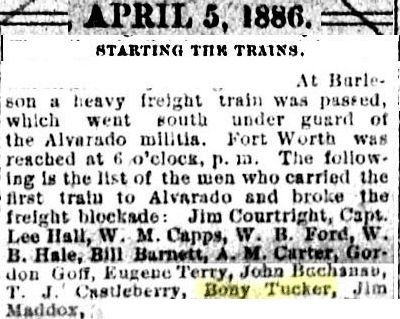

During the railroad strike of 1886 both brothers were guards—led by Jim Courtright—on the Missouri Pacific train that attempted to break the strikers’ blockade. When the train was ambushed by strikers, both brothers took part in the Battle of Buttermilk Junction.

During the railroad strike of 1886 both brothers were guards—led by Jim Courtright—on the Missouri Pacific train that attempted to break the strikers’ blockade. When the train was ambushed by strikers, both brothers took part in the Battle of Buttermilk Junction.

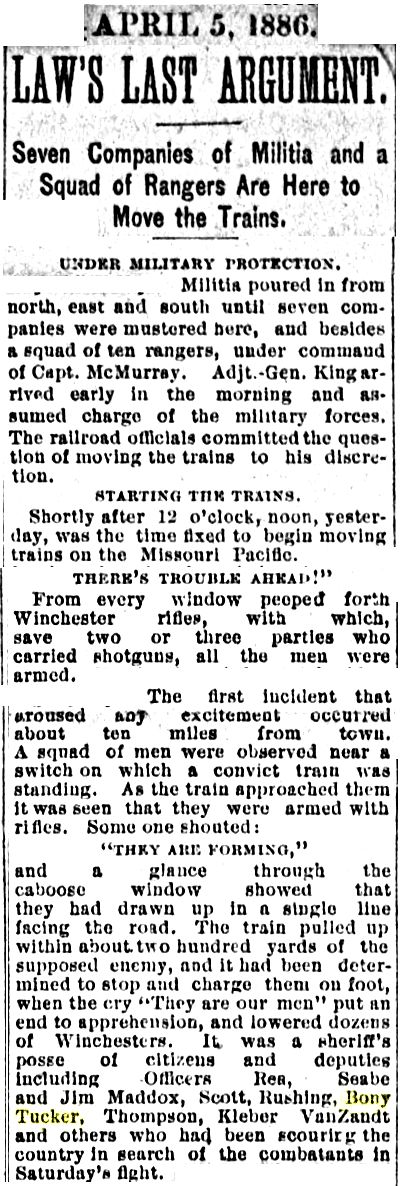

As a result of the shootout, Fort Worth was effectively put under martial law as militia groups, Texas Rangers, and civilian posses patrolled the city to reduce the threat of more strike violence. Bony—with brothers James and Sebe Maddox, and “Kleber VanZandt”—was a member of a posse that searched for the Buttermilk Junction ambushers.

As a result of the shootout, Fort Worth was effectively put under martial law as militia groups, Texas Rangers, and civilian posses patrolled the city to reduce the threat of more strike violence. Bony—with brothers James and Sebe Maddox, and “Kleber VanZandt”—was a member of a posse that searched for the Buttermilk Junction ambushers.

“Kleber VanZandt” probably was Khleber M. Van Zandt Jr., not Sr.

Both Tucker brothers—along with Courtright, William Capps, James Maddox, and Captain Lee Hall—again were guards on the train that was successful in breaking the strikers’ blockade.

Both Tucker brothers—along with Courtright, William Capps, James Maddox, and Captain Lee Hall—again were guards on the train that was successful in breaking the strikers’ blockade.

“Captain Lee Hall” probably was the Captain Lee Hall with whom Comanche chief Quanah Parker was to meet in Fort Worth in 1885 when Parker was overcome by gas in his hotel room.

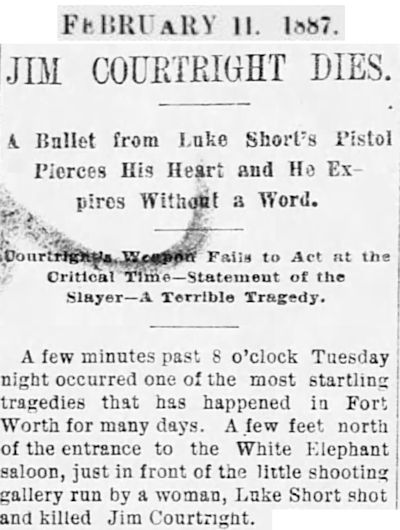

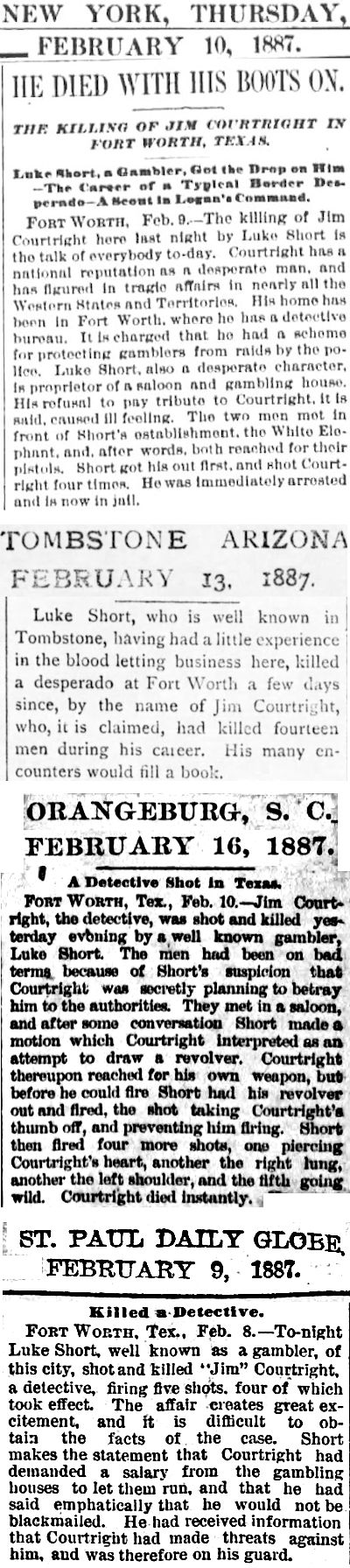

Fast-forward to February 8, 1887. Luke Short fatally shot Jim Courtright outside the White Elephant Saloon.

Fast-forward to February 8, 1887. Luke Short fatally shot Jim Courtright outside the White Elephant Saloon.

The killing of Jim Courtright was news around the country.

The killing of Jim Courtright was news around the country.

At the time of the shooting, the brothers Tucker were less than a block from the White Elephant Saloon. Bony recalled to a Fort Worth Gazette reporter:

At the time of the shooting, the brothers Tucker were less than a block from the White Elephant Saloon. Bony recalled to a Fort Worth Gazette reporter:

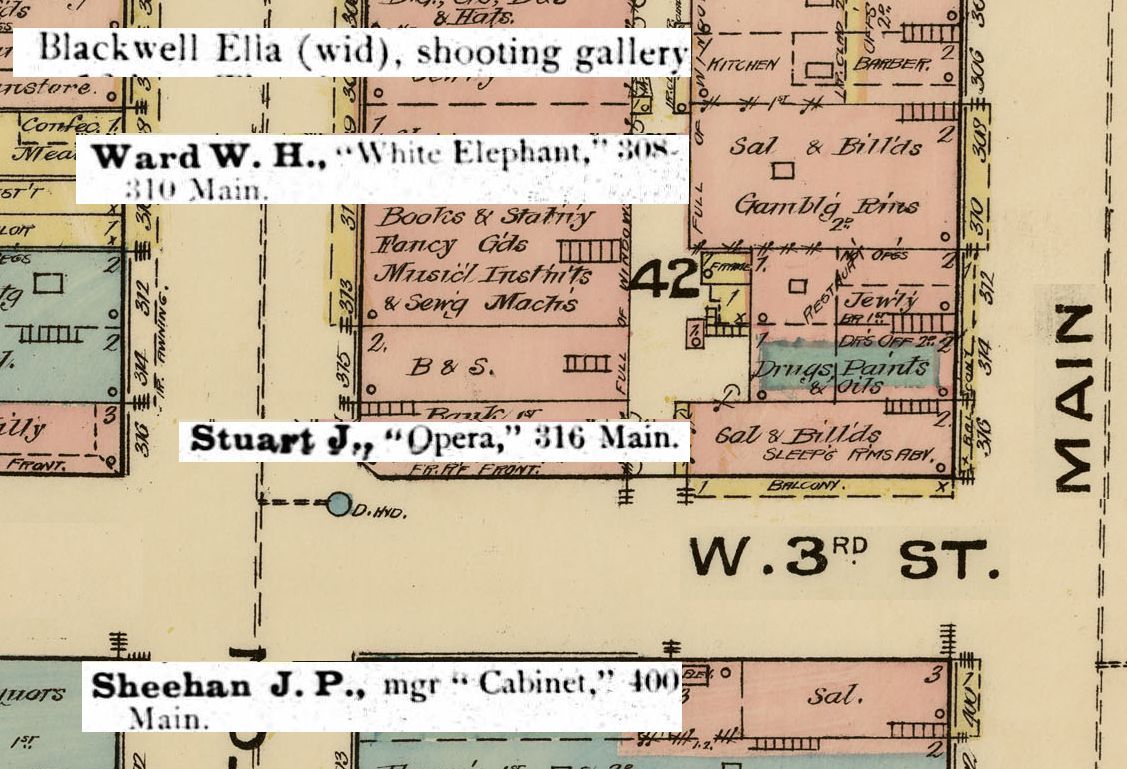

“I was standing chatting with District Clerk [L. R.] Taylor and my brother Rowan in front of the Cabinet Saloon [see map], corner of Main and Third streets. We had been talking of going to the show downtown. A few minutes before that, however, a man had approached me and asked me if I had two guns. He appeared considerably excited and said that there was going to be trouble between Jim Courtright and Luke Short. I told him he couldn’t get a gun from me. This was about 7:30 o’clock and was the first intimation I had that there was going to be any trouble. I repeated what the party had told me to my brother and remarked that I wanted him to stay by me; if there was going to be trouble it must be stopped, and I wanted somebody that I could rely on. Just about the time this was said, the crack of a pistol rang out, and I knew that the trouble opened up. Then we ran toward the firing, and about the time John Stuart’s corner [Opera Saloon, Main at 3rd Street; see map] was reached another shot was heard.”

Now the lives of brothers Rowan and Bony Tucker Jr. were running in parallel both figuratively and literally. Both men were officers of the law, both were running up Main Street to answer the call of duty in the form of gunshots.

Bony Tucker continued his narrative:

“Two more reports followed in quick succession, and then a fifth and the last just as I came upon Luke Short, who was at that time the only man that I saw. He was standing some twelve or fifteen steps north of the shooting gallery [see map]. Fearing that he might shoot me in the excitement of the moment, I dodged around him and grabbed his pistol. It was a Colt’s 45-caliber. Rowan also grabbed him, and about that time officer [J. W.] Pemberton came up. Then I saw Courtright. He had fallen just inside the shooting gallery, his feet extending out into the sidewalk. When I reached him he was dying, and though I bent over and spoke to him, he never articulated a syllable. [John J. Fulford, who also was among the first to reach the scene, would testify that Courtright’s last words were, “Ful, they’ve got me.”]

“He [Courtright] grasped his gun in one hand, a 45 of the same make as the one that killed him. The chambers were full of cartridges, showing that he had failed to get in a shot. Three bullets had taken effect. One broke his right thumb, the second passed through his heart, and the third struck him in the right shoulder. I believe it was the second shot fired that killed him. He was a dead man within five minutes after I reached him. Sheriff Shipp, Marshal Rea, Rowan Tucker, and myself then took Short to the county jail.”

As Bony Tucker escorted Luke Short to jail, the calendar of Bony Tucker’s life had nine months left on it.

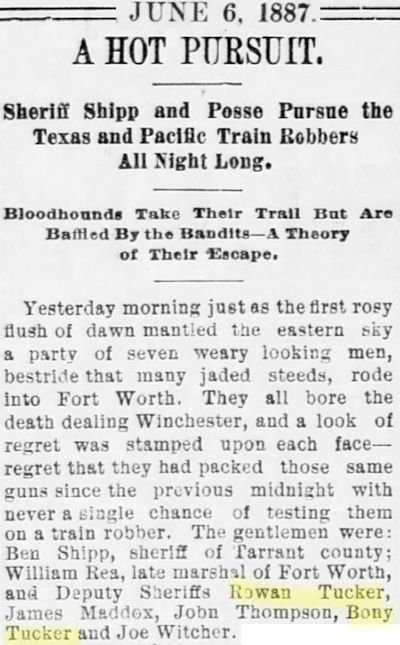

But for a while the lives of the Tucker brothers continued to run in parallel. In June the brothers, along with the ubiquitous James Maddox, were members of a posse who searched for the Burrow gang after the gang robbed a Texas & Pacific train on Mary’s Creek near Benbrook.

But for a while the lives of the Tucker brothers continued to run in parallel. In June the brothers, along with the ubiquitous James Maddox, were members of a posse who searched for the Burrow gang after the gang robbed a Texas & Pacific train on Mary’s Creek near Benbrook.

But by August the lives of the two brothers had begun to diverge. Bony Tucker was working as a guard on the northbound Santa Fe passenger train. The train’s first stop out of Fort Worth was in Gainesville. There Bony Tucker met Hazel Creeland. Hazel Creeland was the proprietress of Hazelwood, a brothel in Gainesville. Creeland would later testify that she “frequently” met Tucker at the train station and returned to her brothel with him.

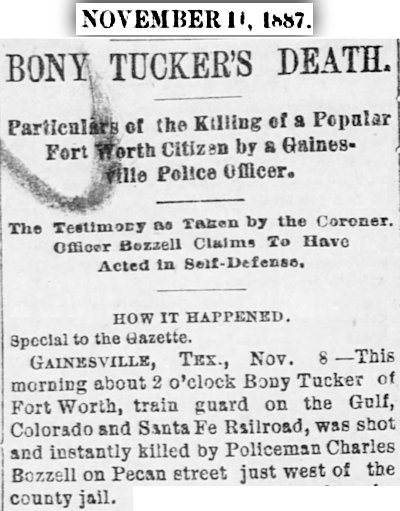

On November 8, nine months to the day after brothers Rowan and Bony Tucker responded to the Courtright-Short shooting, Bony Tucker was in Gainesville in the company of Hazel Creeland.

According to the Times-Democrat of New Orleans: “Tucker arrived here [Gainesville] on the 10:30 p.m. train from the south the evening before and had repaired to a notorious house in the western part of Gainesville, where he had spent the evening in high carnival, drinking and carousing. About 2 o’clock this morning he secured a carriage and took with him a woman named Hazel, formerly Mrs. Dixie Barlow, and with her he proceeded to take in the town.”

Both Tucker and Creeland were well known to Gainesville police: Tucker as a fellow lawman and Creeland as a madam. She had been fined several times for operating a brothel.

The Fort Worth Gazette detailed the testimony given by witnesses at a coroner’s inquest:

The Fort Worth Gazette detailed the testimony given by witnesses at a coroner’s inquest:

“Mack S. Vining, the hack [carriage] driver, testified as follows:

“‘Tucker got into the hack at Turner’s Saloon and was driven to Hazelwood, a bawdy house in the western part of the city. I then drove deceased and Hazel, the keeper of the house, to the Star beer ball and got drinks for them. I then started home with them. After passing the jail [officer] Charles Bozzell and [officer] Louis Brigman ran out and wanted to stop them. The deceased told me to drive on.

Charley Bozzell ran on ahead of us and caught my horse by the bridle. The deceased then got out of the carriage with his pistol in his hand. Bozzell and Brigman drew their pistols. Bozzell told the deceased he was going to arrest him for riding with a prostitute. The deceased said he was not riding with any prostitute, that she did not have to pay fines, and that he would not have to pay a fine either; that if he had to pay a fine the officers could get into the hack and go down with him, or they could see him in the morning, and he would pay it. Bozzell told him he had to go with him. The deceased said he was not going. As he said that Bozzell said: “You have to go” and then jerked out his pistol.’”

Freeze frame! At this point Bony Tucker was still in control of his fate. He had choices, one of which was to pay the fine and get back to “drinking and carousing.” Would he make a choice that he would live to regret? No. He would make a choice that he would not live to regret.

The Times-Democrat wrote:

“Tucker . . . placed the muzzle [of his revolver] against the breast of Policeman Bozzell, who was too quick for the antagonist and opened fire first, shooting Tucker through the heart. This was followed by two other shots, each of which passed through the body, coming out at the back, producing instant death.”

The Gazette wrote: “When the body was found by the coroner, where it had fallen, a Colt’s improved forty-five caliber pistol was lying about four inches from his right hand, every chamber of which was loaded.”

Bony Tucker, like Jim Courtright nine months earlier, had not fired a single shot. Tucker was twenty-six years old.

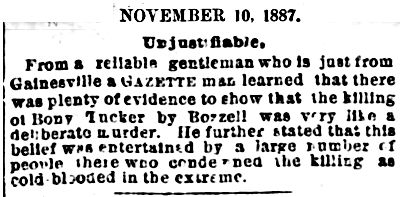

Bony’s friends in Fort Worth believed that Bozzell’s shooting of Tucker was murder, beyond the bounds of a policeman’s authority to use deadly force when making an arrest.

Bony’s friends in Fort Worth believed that Bozzell’s shooting of Tucker was murder, beyond the bounds of a policeman’s authority to use deadly force when making an arrest.

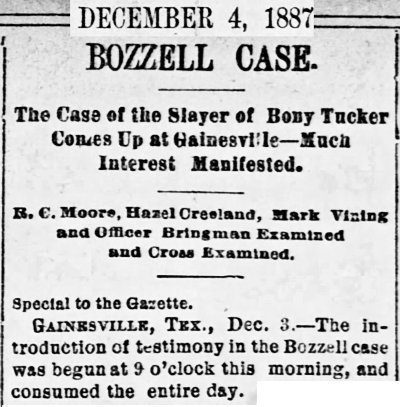

Indeed, officer Bozzell was indicted for murder.

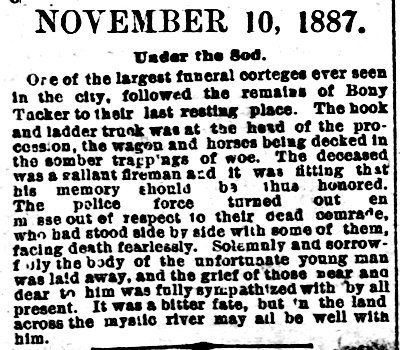

Bony Tucker, like Jim Courtright, had been a member of Fort Worth’s volunteer fire department. Both men received a formal burial by their fellow firemen. The Gazette called Tucker’s funeral procession “one of the largest funeral corteges ever seen in the city.” Horses of the fire department were “decked in the somber trappings of woe.”

Bony Tucker, like Jim Courtright, had been a member of Fort Worth’s volunteer fire department. Both men received a formal burial by their fellow firemen. The Gazette called Tucker’s funeral procession “one of the largest funeral corteges ever seen in the city.” Horses of the fire department were “decked in the somber trappings of woe.”

The Gazette called Tucker’s death “a bitter fate, but in the land across the mystic river may all be well with him.”

Bony Tucker was buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

Bony Tucker was buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

When Charley Bozzell went on trial for murder, among prosecuting attorneys was Fort Worth’s William S. Pendleton, who would have troubles of his own in three years.

When Charley Bozzell went on trial for murder, among prosecuting attorneys was Fort Worth’s William S. Pendleton, who would have troubles of his own in three years.

Under cross-examination Hazel Creeland confirmed that she operated a “bawdy house.”

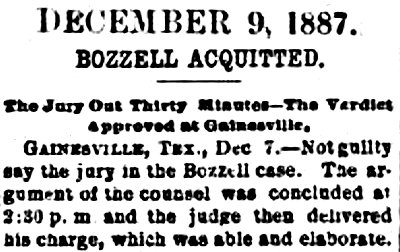

The jury acquitted Bozzell, finding that he had been justified in attempting to arrest Bony Tucker and that Bozzell had acted in self-defense when threatened by Tucker.

The jury acquitted Bozzell, finding that he had been justified in attempting to arrest Bony Tucker and that Bozzell had acted in self-defense when threatened by Tucker.

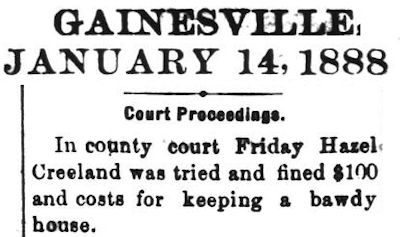

And so ended the short life of Bony Tucker Jr. But for Hazel Creeland, life went on. A month later she was fined for “keeping a bawdy house.”

And so ended the short life of Bony Tucker Jr. But for Hazel Creeland, life went on. A month later she was fined for “keeping a bawdy house.”

Life also went on for surviving brother Rowan. A year after the killing of his brother, Rowan left law enforcement and became an agent for the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad. He held that job the rest of his life. He also would represent the Fifth Ward of his South Side neighborhood for four terms on the city council.

Rowan Tucker died in 1920 at age sixty-five. The Star-Telegram wrote that he had lived the last thirty years of his life on the family homestead on Tucker’s Hill and died “within a stone’s throw of the site where he was born.”

Rowan Tucker died in 1920 at age sixty-five. The Star-Telegram wrote that he had lived the last thirty years of his life on the family homestead on Tucker’s Hill and died “within a stone’s throw of the site where he was born.”

Rowan Tucker, like Bony Tucker Jr., is buried in the family plot in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

Rowan Tucker, like Bony Tucker Jr., is buried in the family plot in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

Rowan Tucker had lived a long life—thirty-three years beyond the short life of his brother.

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade