What connections could there be between . . .

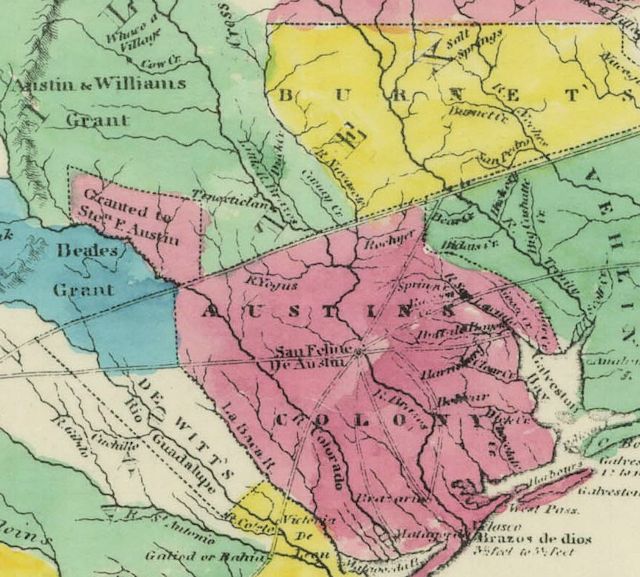

Stephen F. Austin’s Old Three Hundred colonists of early Texas (1833 map from Wikipedia), . . .

Stephen F. Austin’s Old Three Hundred colonists of early Texas (1833 map from Wikipedia), . . .

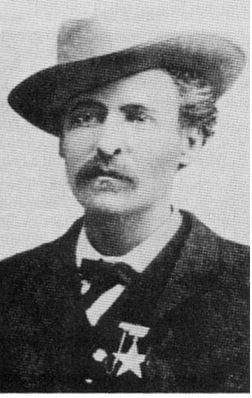

Jim Courtright, . . .

Jim Courtright, . . .

and the man called the “Texas Terror”?

and the man called the “Texas Terror”?

Our first connection is a woman named “Ella.” Ella was born in Galveston in 1857. By 1876 she was living in Fort Worth. She was married and had a baby boy named “Willie.”

The family lived on today’s near South Side. Early on son Willie showed a talent for baseball.

He played sandlot baseball and held his own against older, stronger boys. He attended Fort Worth Panthers games at T&P Park just a few blocks from his home.

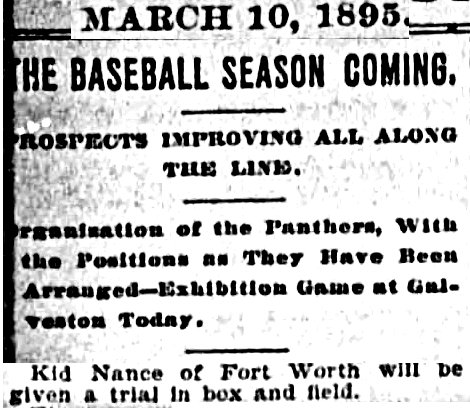

In fact, after graduating from Fort Worth High School, at age eighteen Willie got a tryout with the Panthers. He stood five-foot-seven and weighed 165 pounds—not imposing, but he had a keen eye, strong arm, and fast feet.

In fact, after graduating from Fort Worth High School, at age eighteen Willie got a tryout with the Panthers. He stood five-foot-seven and weighed 165 pounds—not imposing, but he had a keen eye, strong arm, and fast feet.

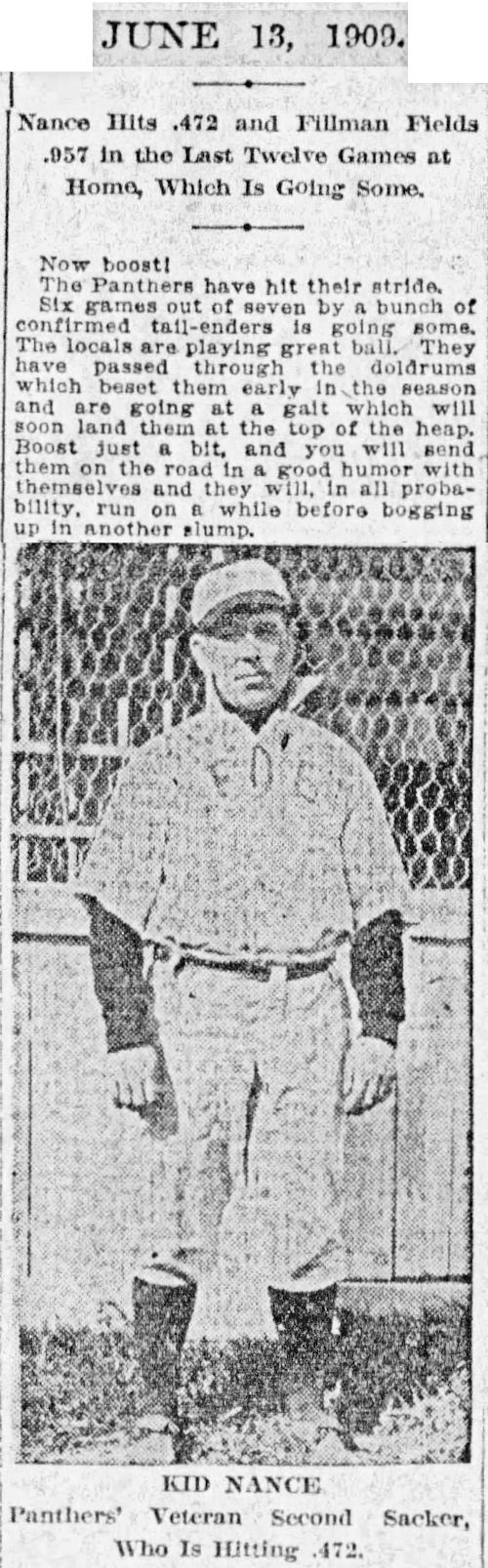

And he had a nickname: “Kid,” given to him because of his youth. Kid Nance would answer to that nickname the rest of his life.

Nance’s tryout earned him a place on the Panthers roster. He played shortstop and left field.

Nance’s tryout earned him a place on the Panthers roster. He played shortstop and left field.

But in May Fort Worth Gazette readers were surprised to read that Kid Nance was now playing for the Sherman team: the Orphans. Odd: There had been no news of a trade. But Kid Nance was green—green as a well-watered infield. He simply went to Sherman on his own and became an Orphan. Very contrary to league rules. He later said the Panthers manager didn’t beef much because the manager didn’t think Kid would be much of a ballplayer.

But in May Fort Worth Gazette readers were surprised to read that Kid Nance was now playing for the Sherman team: the Orphans. Odd: There had been no news of a trade. But Kid Nance was green—green as a well-watered infield. He simply went to Sherman on his own and became an Orphan. Very contrary to league rules. He later said the Panthers manager didn’t beef much because the manager didn’t think Kid would be much of a ballplayer.

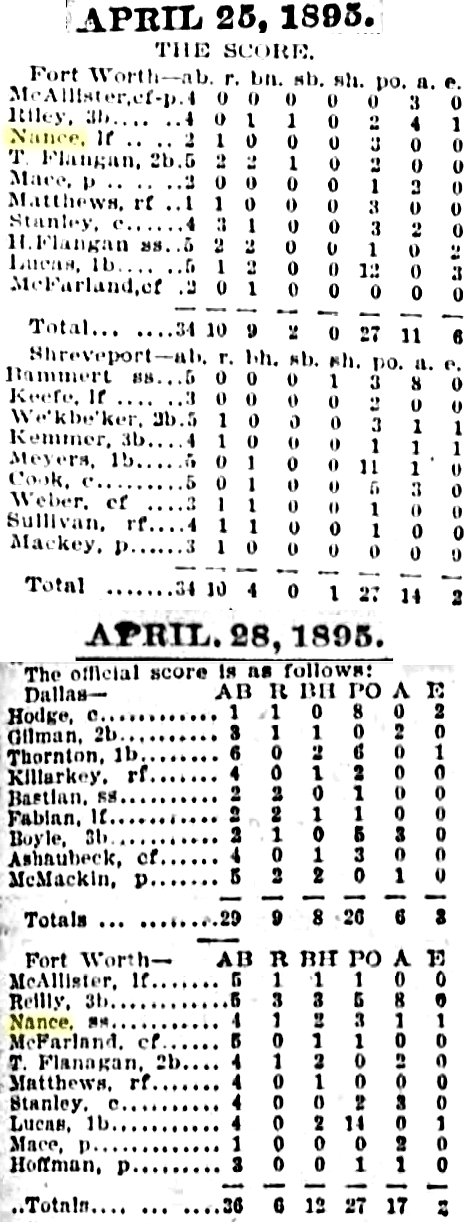

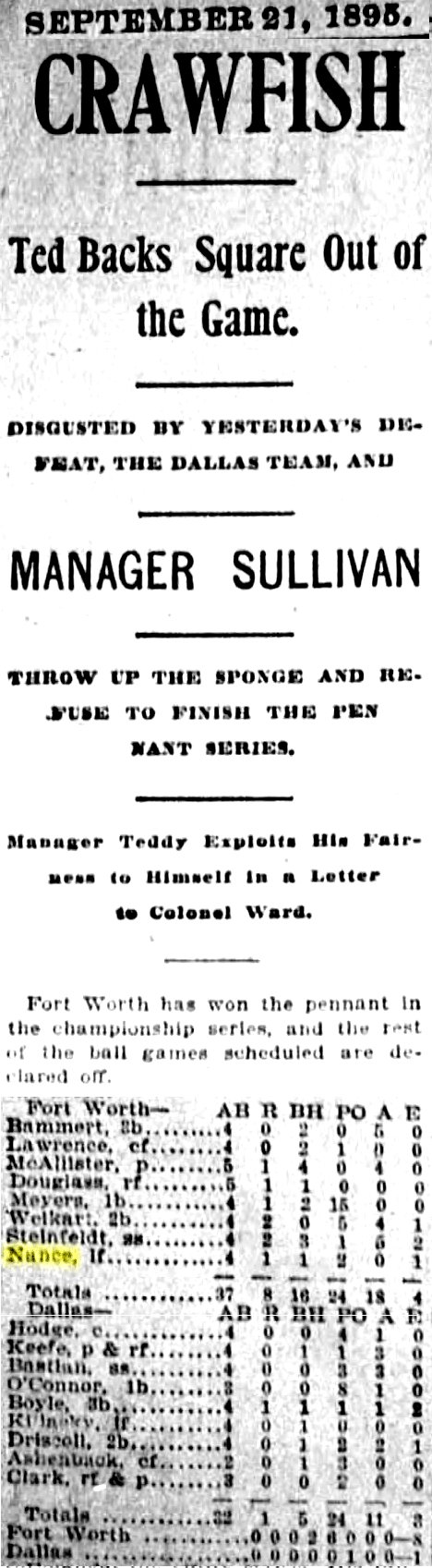

No hard feelings. In fact, Nance boomeranged back to the Panthers in time to help them win their first league championship in a bizarre playoff series that befit the venerable Fort Worth-Dallas rivalry.

No hard feelings. In fact, Nance boomeranged back to the Panthers in time to help them win their first league championship in a bizarre playoff series that befit the venerable Fort Worth-Dallas rivalry.

Kid Nance played for the Panthers again in 1896 but began the 1897 season with the Galveston Sandcrabs of the Texas League. He hit .395 for Galveston, winning the league batting title.

Kid Nance played for the Panthers again in 1896 but began the 1897 season with the Galveston Sandcrabs of the Texas League. He hit .395 for Galveston, winning the league batting title.

And that caught the eye of the Louisville Colonels of the National League.

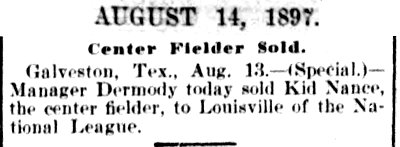

On August 13, 1897—just seventy-six years after Stephen F. Austin’s colony opened for settlement—Kid Nance was sold to Louisville, becoming Fort Worth’s first major league player.

Sporting Life newspaper wrote of Nance’s last game in Galveston in 1897: “Kid Nance walked to the plate for the last time, and the shouting was terrific. Everyone knew that he had signed a contract with the Louisville Club of the National League.” After the game “a carriage was in waiting, and . . . it was driven around in front of the grandstand, where his legion of friends bid him farewell. Nance is considered to be one of the finest outfielders in the country and a good hitter, having always batted over .300.”

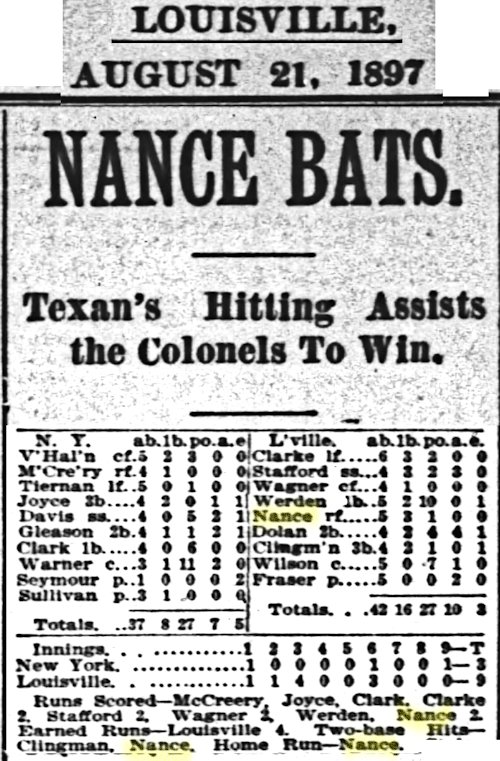

Louisville Colonel Kid Nance went hitless in his first game in the National League. But in his second game he hit a single, double, and home run to lead the Colonels to a win over the New York Giants.

Louisville Colonel Kid Nance went hitless in his first game in the National League. But in his second game he hit a single, double, and home run to lead the Colonels to a win over the New York Giants.

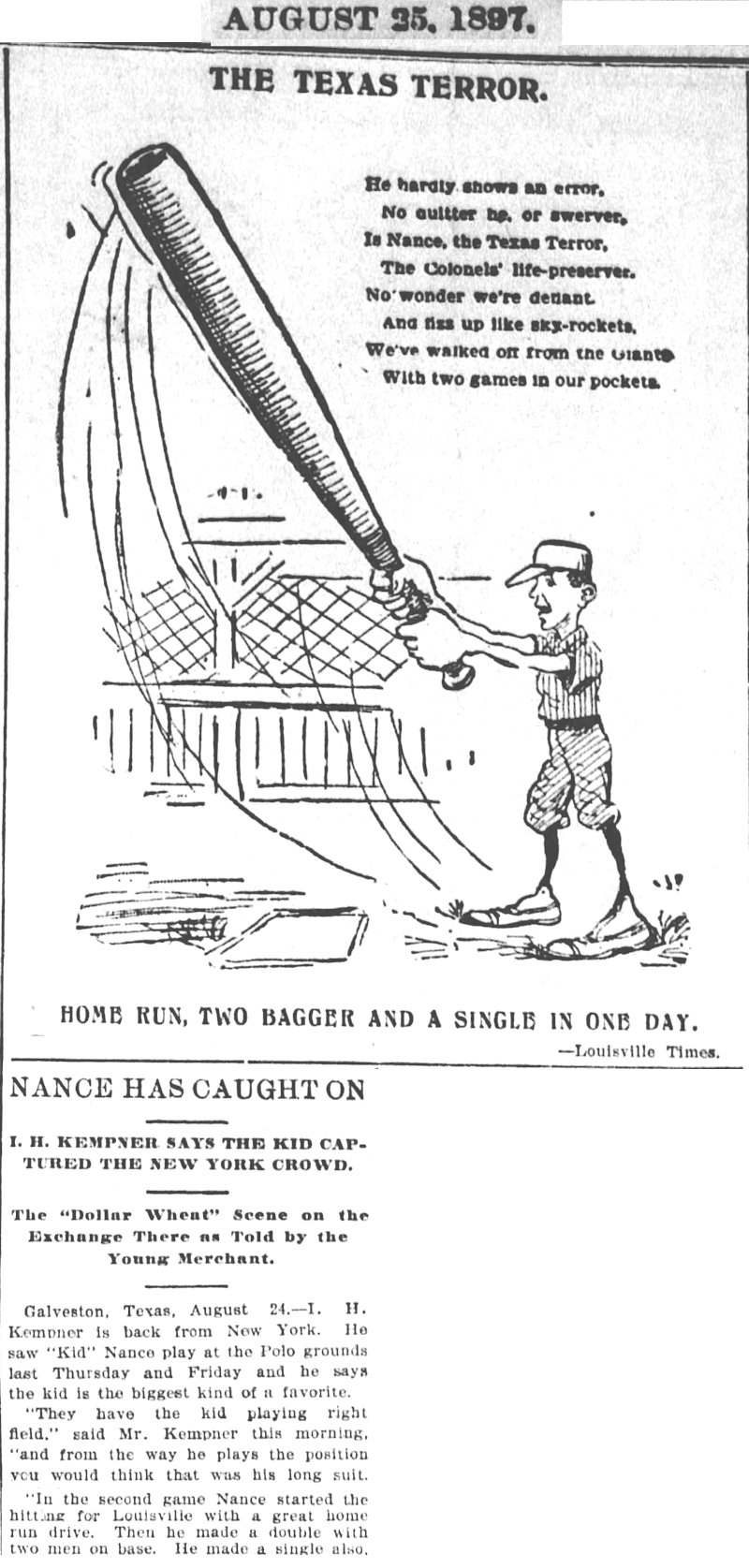

The “Texas Wonder,” one New York City newspaper called him.

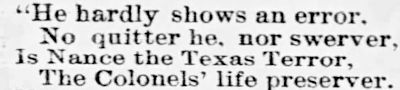

The Louisville newspaper was so enthralled with Nance that it printed this cartoon and poem about “Nance, the Texas Terror.”

The Louisville newspaper was so enthralled with Nance that it printed this cartoon and poem about “Nance, the Texas Terror.”

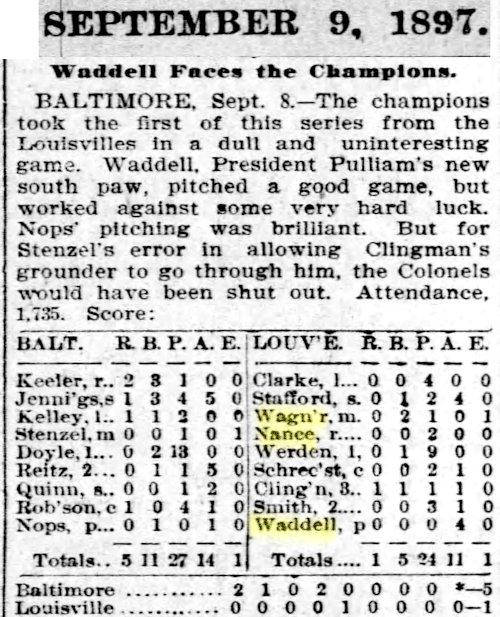

In addition to the Texas Terror, in 1897 Louisville signed two future Hall of Famers: Honus Wagner and Rube Waddell. In fact, Wagner and Waddell were ranked as the top two rookies of the year. Kid Nance was ranked twenty-fifth.

In addition to the Texas Terror, in 1897 Louisville signed two future Hall of Famers: Honus Wagner and Rube Waddell. In fact, Wagner and Waddell were ranked as the top two rookies of the year. Kid Nance was ranked twenty-fifth.

Nance began the 1898 season with Louisville, but after twenty-two games and a .316 batting average, he was released. He landed in Paterson, New Jersey, in the Atlantic League. In 1899 and 1900 he played for the Minneapolis Millers of the Western League. He hit .269 in 1899 and .309 in 1900. But in 1900 he also led the league in errors with seventy-three.

He began the 1901 season with the Grand Rapids Furniture Makers of the Western Association (not to be confused with the Western League) but was soon called up to the Bigs for the second time: He signed with the Detroit Tigers of the newly formed American League.

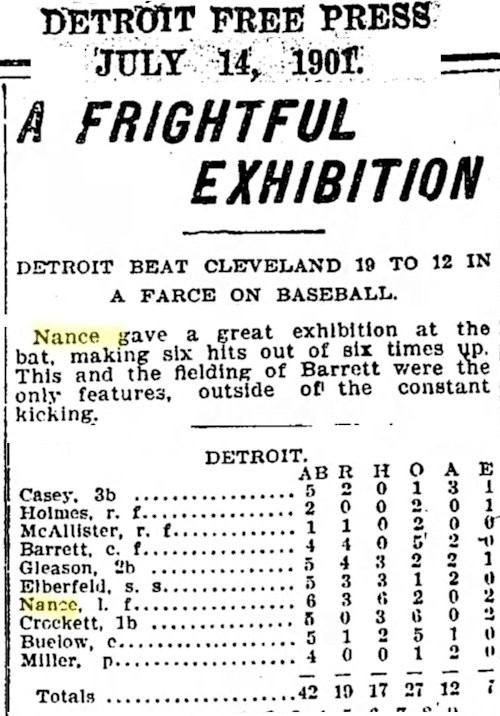

On July 13, 1901 Kid Nance had another memorable game: He went six for six as the Tigers beat the Cleveland Blues 19-12.

On July 13, 1901 Kid Nance had another memorable game: He went six for six as the Tigers beat the Cleveland Blues 19-12.

Nance played in 132 games for the Tigers in 1901. In 466 at-bats he hit .280 and led the league in sacrifice hits with twenty-four.

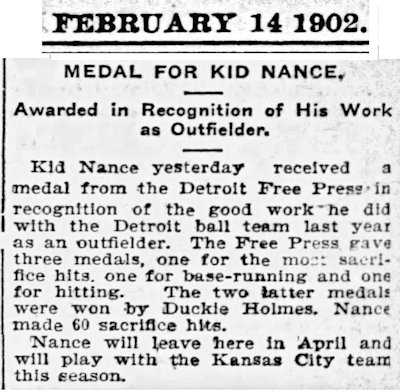

In 1902 the Detroit Free Press newspaper gave Nance a medal in appreciation of his performance in his first season as a Tiger in 1901. But his first season was also his last season: By the time he got the medal he was on his way to another team: Kansas City in the American Association.

In 1902 the Detroit Free Press newspaper gave Nance a medal in appreciation of his performance in his first season as a Tiger in 1901. But his first season was also his last season: By the time he got the medal he was on his way to another team: Kansas City in the American Association.

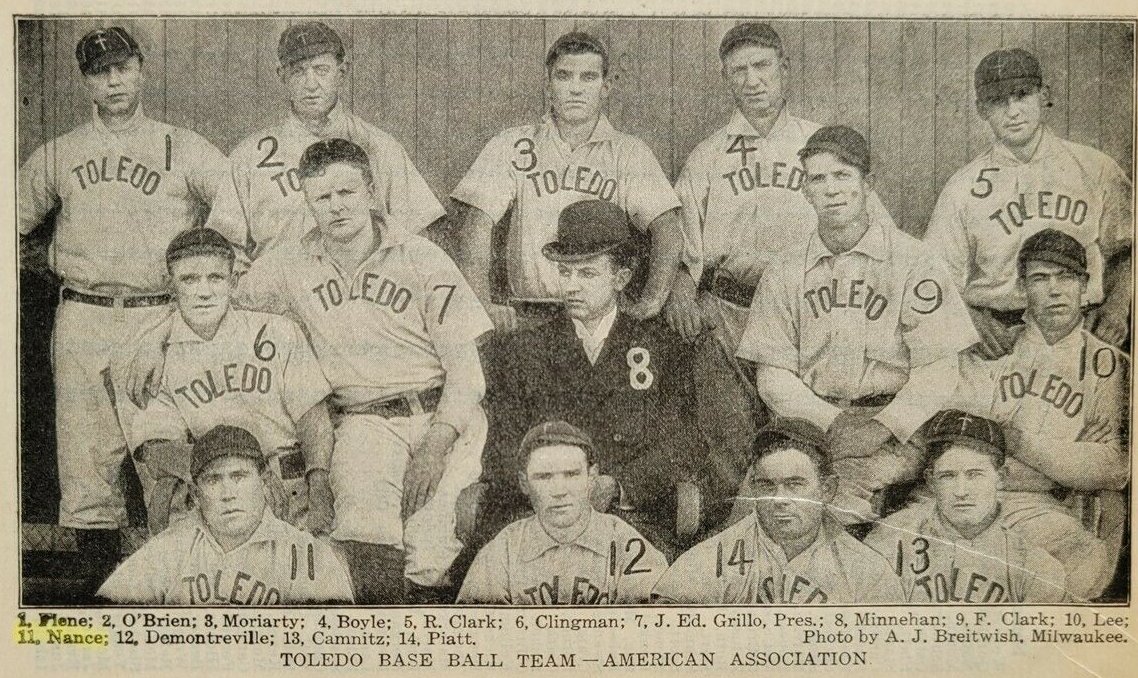

He spent the next five years in the American Association with Kansas City and then Toledo. He was one of the best outfielders and hitters in the league.

The 1905 Toledo Mud Hens.

The 1905 Toledo Mud Hens.

Nance batted .274 for Toledo in 1906 with seven triples and twenty doubles.

Like many a minor league player, Nance was a pinball with cleats. He ricocheted from Kansas City to Toledo to Sioux City, South Dakota, of the Western League in 1907 . . .

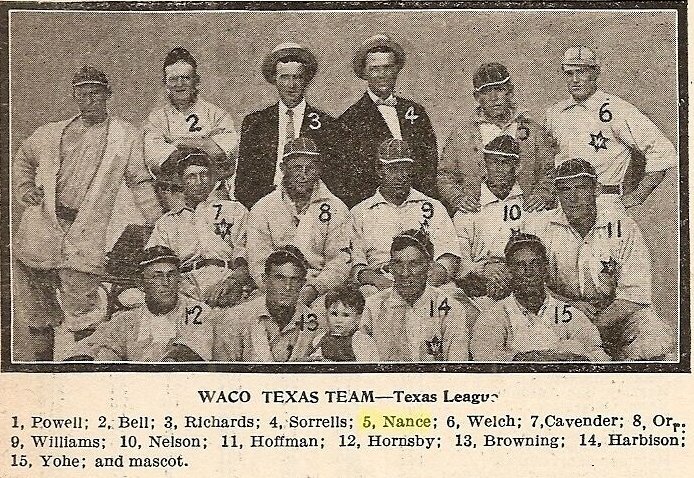

to the Waco Navigators of the Texas League in 1908 (the “Hornsby” is Rogers Hornsby’s older brother Everett) . . .

to the Waco Navigators of the Texas League in 1908 (the “Hornsby” is Rogers Hornsby’s older brother Everett) . . .

and back to Fort Worth in 1909. Even though he was hitting .472 for the Panthers in June, he ended the season with the Shreveport Pirates.

and back to Fort Worth in 1909. Even though he was hitting .472 for the Panthers in June, he ended the season with the Shreveport Pirates.

And in 1910 he managed the Jackson, Mississippi, Senators of the Cotton States League.

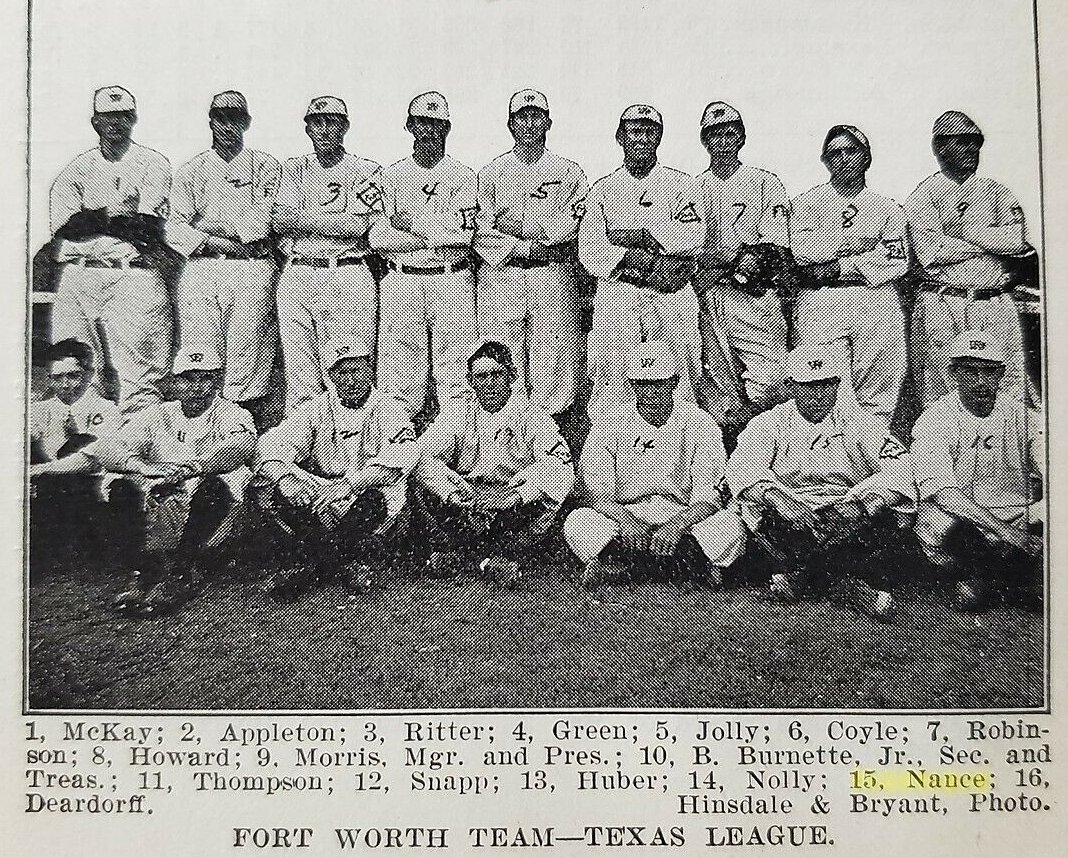

But he boomeranged back to the Panthers in 1911. Walter J. Morris was team manager.

But he boomeranged back to the Panthers in 1911. Walter J. Morris was team manager.

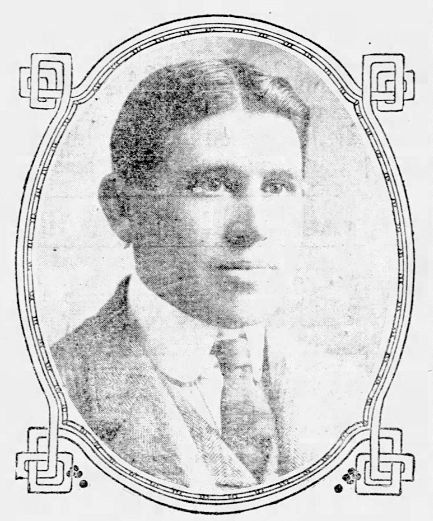

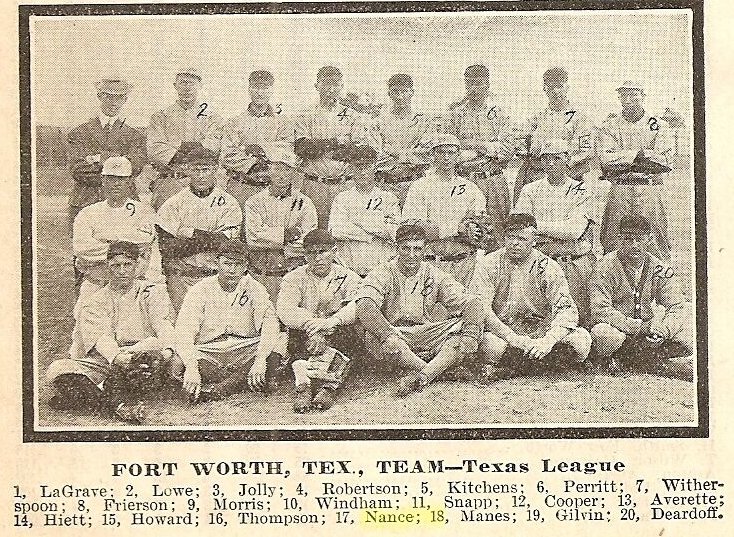

Paul LaGrave was secretary of the Panthers in 1912.

Paul LaGrave was secretary of the Panthers in 1912.

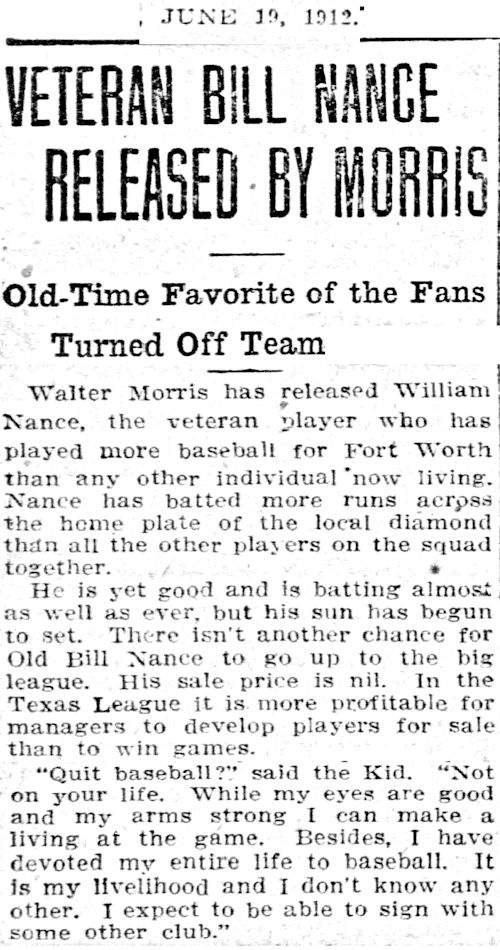

By 1912 Kid Nance was no kid. He was thirty-six years old. He had played three seasons in the major leagues and fifteen in the minors. Now his legs were slower, his eye not as keen, his arm not as strong. He was finished as a player.

By 1912 Kid Nance was no kid. He was thirty-six years old. He had played three seasons in the major leagues and fifteen in the minors. Now his legs were slower, his eye not as keen, his arm not as strong. He was finished as a player.

But he still had plenty of baseball savvy.

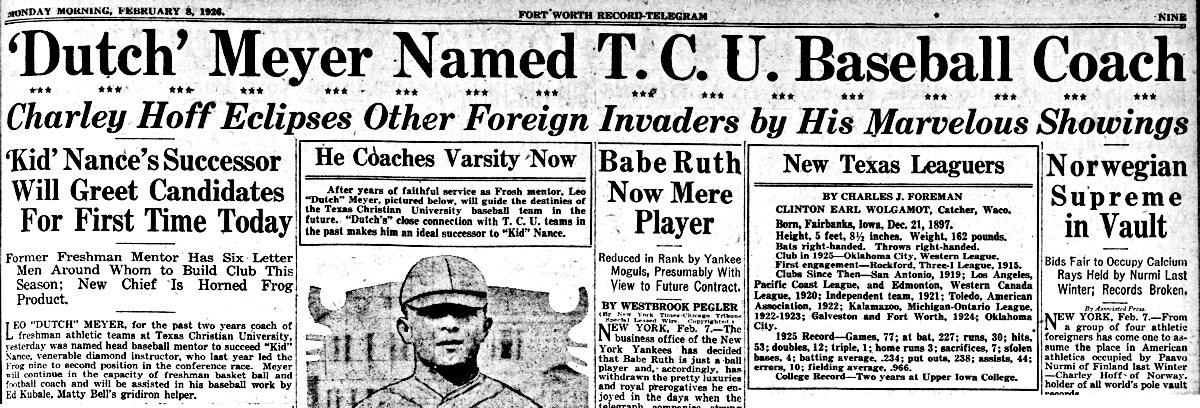

In 1913 Nance was his own doubleheader. First he became baseball coach at TCU.

In 1913 Nance was his own doubleheader. First he became baseball coach at TCU.

In March Nance’s TCU team beat the Panthers.

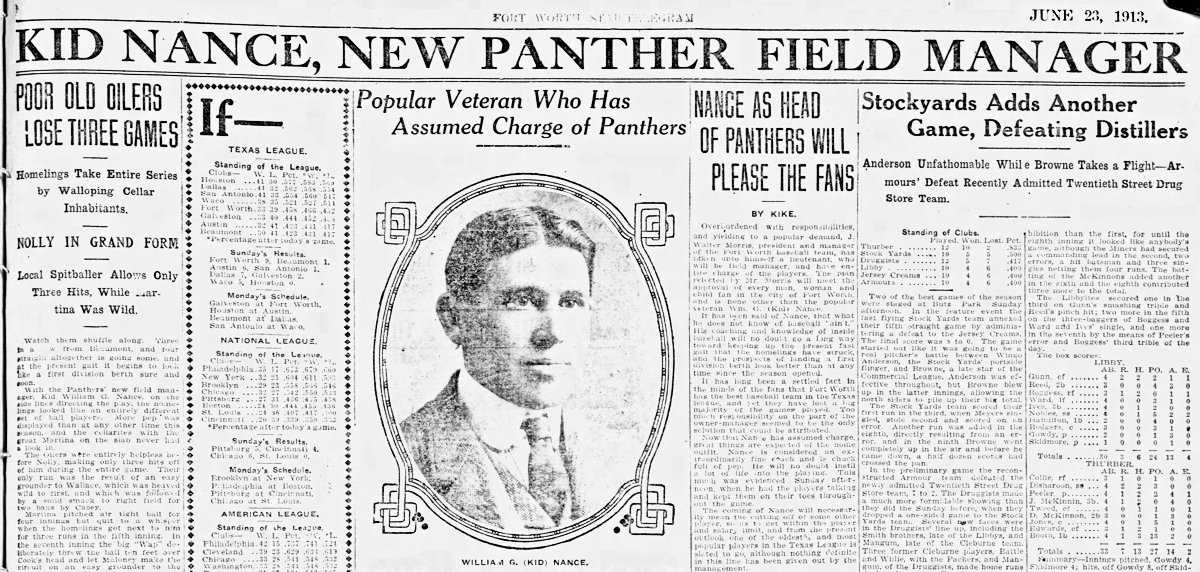

Then in June Nance became manager of the Panthers.

Then in June Nance became manager of the Panthers.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “Kid Nance, the new field manager, is one of the most popular players that ever donned a uniform. He is known wherever baseball is known. . . . It has been said of Nance that what he doesn’t know of baseball ‘ain’t.’”

As manager of the Panthers Nance was the first manager in the Texas League to incorporate soccer into spring training. Soon other managers followed suit. And in 1917 TCU athletic director Milton Daniel (as in “Daniel-Meyer Athletics Complex”) would add soccer to baseball spring training.

Nance managed the Panthers on and off for three seasons. In 1914 the Panthers’ home park, named for longtime club owner Walter J. Morris, was renamed “Panther Park.”

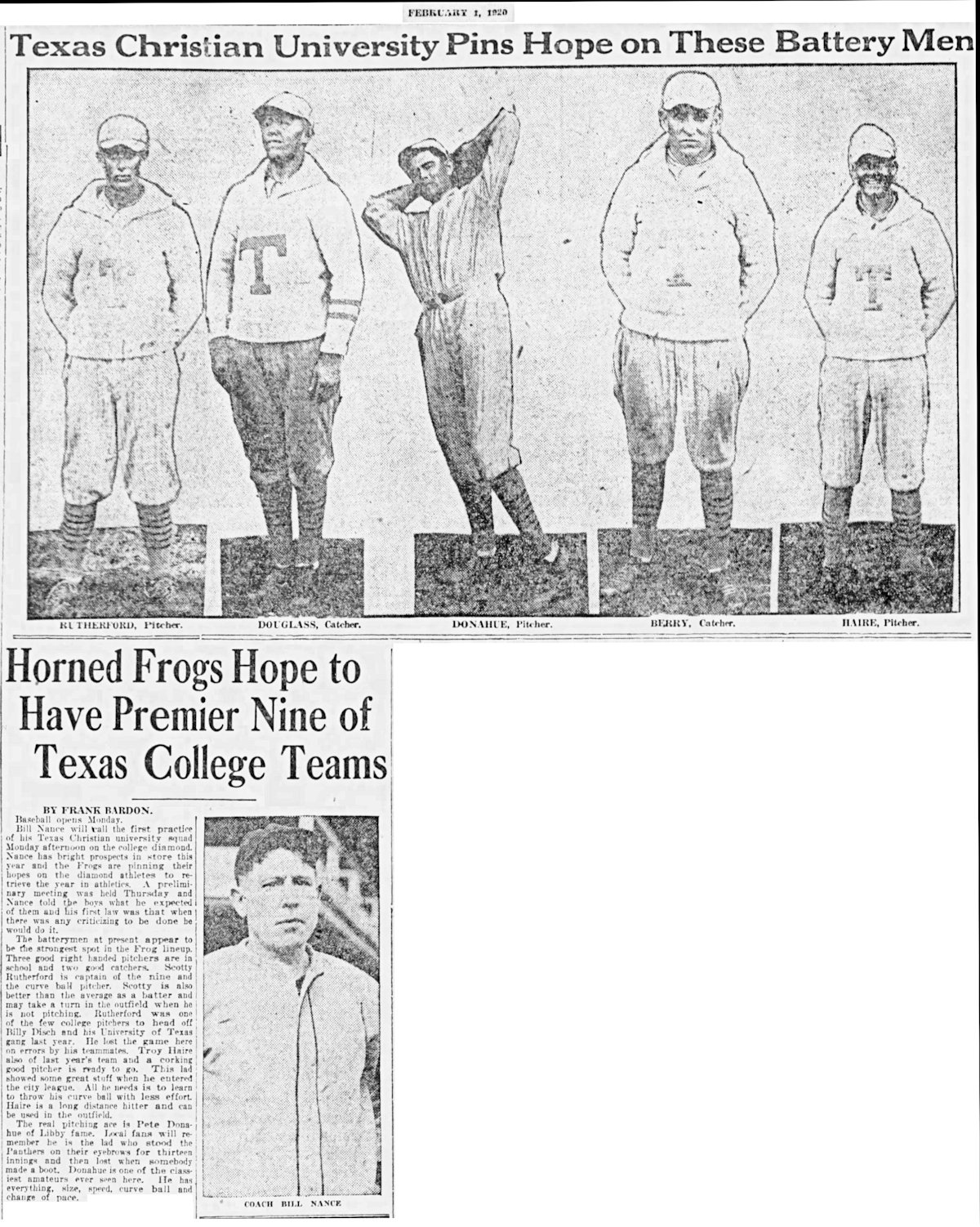

In 1920 Nance was again hired to coach baseball at TCU. Among his players were Dutch Meyer and Herman Clark, both of whom have athletic facilities named for them.

In 1920 Nance was again hired to coach baseball at TCU. Among his players were Dutch Meyer and Herman Clark, both of whom have athletic facilities named for them.

Under Nance TCU won four Texas Interscholastic Athletic Association championship titles.

But in 1926, after TCU finished second in the Southwest Conference, Nance was replaced as baseball coach by former protégé Dutch Meyer. Kid was fifty years old. After thirty-one years his baseball career was over.

But in 1926, after TCU finished second in the Southwest Conference, Nance was replaced as baseball coach by former protégé Dutch Meyer. Kid was fifty years old. After thirty-one years his baseball career was over.

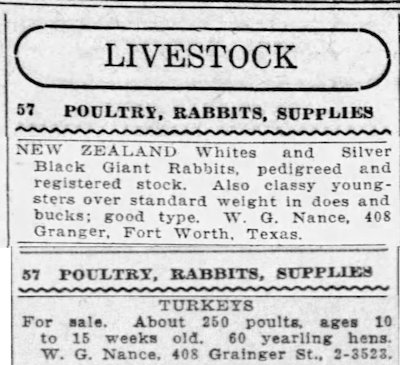

He spent his final years breeding bird dogs . . .

and rabbits and turkeys.

and rabbits and turkeys.

In poor health after age seventy, Nance lost a leg, could no longer attend local baseball games but followed the sport on the radio and in the newspapers. After his wife Fay died he lived the last years of his life in a rest home.

When Kid Nance died in 1958 at age eighty-one, fewer than fifty people attended his funeral.

When Kid Nance died in 1958 at age eighty-one, fewer than fifty people attended his funeral.

His pallbearers were former Panthers players.

Kid Nance is buried—without a marker—in Rose Hill Cemetery.

And now back to those connections:

Kid Nance’s obituary said he had kept “much of his life a secret.” But after he died, the banker who handled Nance’s finances revealed three claims made by Nance: (1) His real name was “Willie C. Cooper,” (2) he was a “grandson” of Stephen F. Austin colonist William Bloodworth, and (3) after Willie’s father died, Willie’s mother married a man named “Nance.”

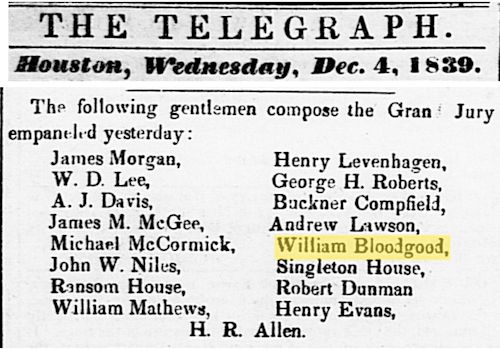

Let’s fact-check those claims. For starters, there was no Austin colonist named “William Bloodworth.” Ah, but a “William Bloodgood” was among Austin’s original colonists: the Old Three Hundred. According to the Texas State Historical Association, Bloodgood was born in New York State or New Jersey about 1800.

Let’s fact-check those claims. For starters, there was no Austin colonist named “William Bloodworth.” Ah, but a “William Bloodgood” was among Austin’s original colonists: the Old Three Hundred. According to the Texas State Historical Association, Bloodgood was born in New York State or New Jersey about 1800.

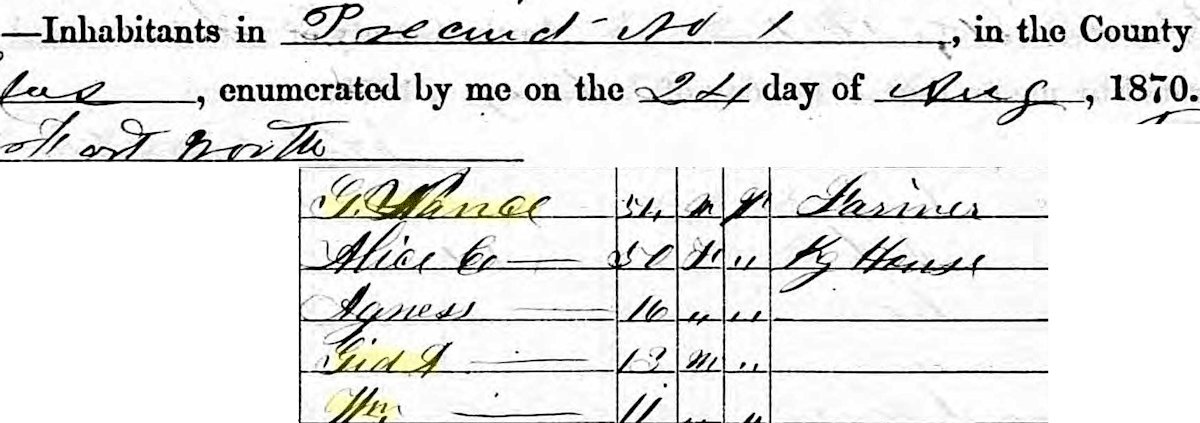

And there was a Nance family in Fort Worth in the late nineteenth century. Gideon Allen Nance, known as “Squire,” was a lawyer, had served as justice of the peace, county clerk, and district clerk. Gideon had two sons: William F. and Gideon Allen Jr. (More about William F. below.)

And there was a Nance family in Fort Worth in the late nineteenth century. Gideon Allen Nance, known as “Squire,” was a lawyer, had served as justice of the peace, county clerk, and district clerk. Gideon had two sons: William F. and Gideon Allen Jr. (More about William F. below.)

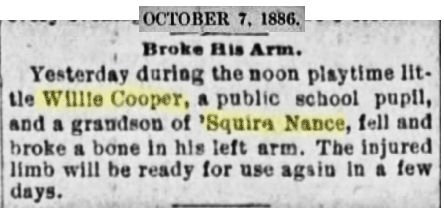

And Gideon Nance Sr. did have a grandson named “Willie Cooper.”

And Gideon Nance Sr. did have a grandson named “Willie Cooper.”

So far, so good.

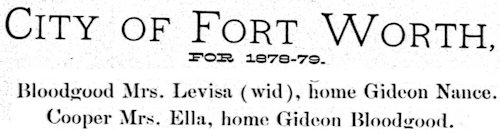

But wait! There’s more. There was a Bloodgood in the Nance household: the widow Levisa Bloodgood. I believe the 1878 city directory entry that shows Ella Cooper residing with “Gideon Bloodgood” is an error. She was residing, along with Levisa Bloodgood, with Gideon Nance. A search of city directories and newspaper archives finds no “Gideon Bloodgood” in Fort Worth.

But wait! There’s more. There was a Bloodgood in the Nance household: the widow Levisa Bloodgood. I believe the 1878 city directory entry that shows Ella Cooper residing with “Gideon Bloodgood” is an error. She was residing, along with Levisa Bloodgood, with Gideon Nance. A search of city directories and newspaper archives finds no “Gideon Bloodgood” in Fort Worth.

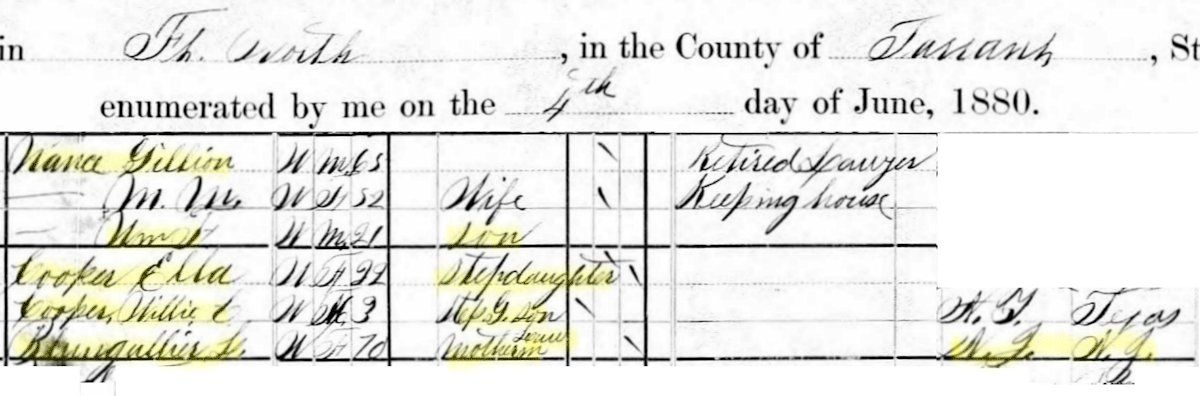

By 1880 Gideon Nance Sr. had retired and remarried: “M. M.” (possibly “Minerva M.”) was his second wife. Living with the couple were son William F., stepdaughter Ella Cooper, stepgrandson Willie C. Cooper, and mother-in-law L. Blungullier, age seventy. Note that L. Blungullier said her parents were born in New Jersey—one of the two states where Austin colonist William Bloodgood is thought to have been born. But I can’t find hide nor hair of the surname “Blungullier.” Perhaps the census enumerator misheard. The surname “Bloodgood” is an anglicized form of the Dutch surname “Bloetgoet.”

By 1880 Gideon Nance Sr. had retired and remarried: “M. M.” (possibly “Minerva M.”) was his second wife. Living with the couple were son William F., stepdaughter Ella Cooper, stepgrandson Willie C. Cooper, and mother-in-law L. Blungullier, age seventy. Note that L. Blungullier said her parents were born in New Jersey—one of the two states where Austin colonist William Bloodgood is thought to have been born. But I can’t find hide nor hair of the surname “Blungullier.” Perhaps the census enumerator misheard. The surname “Bloodgood” is an anglicized form of the Dutch surname “Bloetgoet.”

Regardless, surely “L. Blungullier” and “Levisa Bloodgood” were the same person. Gideon Sr. married “M. M. Blungullier,” and her mother, daughter, and grandson moved in with them.

Thus, the 1880 census ties together the claims related by Kid Nance’s banker: “Willie C. Cooper” had connections to the surnames “Bloodgood” and “Nance.”

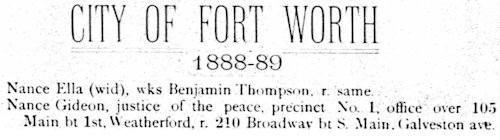

In 1888 “Ella Nance” was working and living at Benjamin Thompson’s Thompson House hotel. Had the surname change from “Cooper” to “Nance” taken place?

In 1888 “Ella Nance” was working and living at Benjamin Thompson’s Thompson House hotel. Had the surname change from “Cooper” to “Nance” taken place?

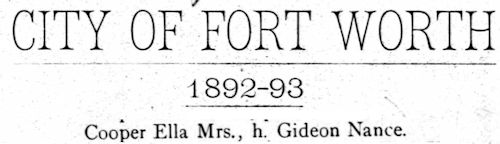

But in 1892 “Ella Cooper” was in the Nance household. (In 1936 Ella would be living with her son when she died, by then the widow of David F. Rundle.)

But in 1892 “Ella Cooper” was in the Nance household. (In 1936 Ella would be living with her son when she died, by then the widow of David F. Rundle.)

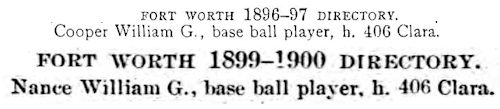

Although Willie C. Cooper was already called “Kid Nance” when he tried out for the Panthers in 1895, these city directory listings show that by 1896 he was “Willie G. Cooper” and by 1899 “Willie G. Nance.”

Although Willie C. Cooper was already called “Kid Nance” when he tried out for the Panthers in 1895, these city directory listings show that by 1896 he was “Willie G. Cooper” and by 1899 “Willie G. Nance.”

Hmmm. But that banker had said that Willie’s middle initial was “C.”

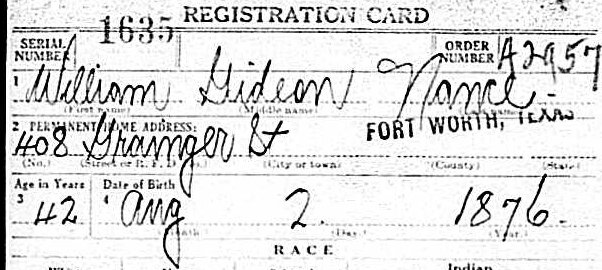

Ah, but on his 1918 draft registration card, Kid Nance, who lived much of his adult life at 408 Grainger Street on the near South Side, listed his name as “William Gideon Nance.” So Willie Cooper took the “Nance” surname and the “Gideon” first name. But did he take the “Gideon” from Sr. or Jr.? Who was Willie’s stepfather: Gideon Allen Nance Jr. or brother William F. Nance?

Ah, but on his 1918 draft registration card, Kid Nance, who lived much of his adult life at 408 Grainger Street on the near South Side, listed his name as “William Gideon Nance.” So Willie Cooper took the “Nance” surname and the “Gideon” first name. But did he take the “Gideon” from Sr. or Jr.? Who was Willie’s stepfather: Gideon Allen Nance Jr. or brother William F. Nance?

I vote for William F. because he was the only son living in the Nance household in 1880.

And who was William F. Nance?

To find William F. Nance’s place in Fort Worth history trivia, let us go back in time eight months before Willie C. Cooper/Kid Nance was born.

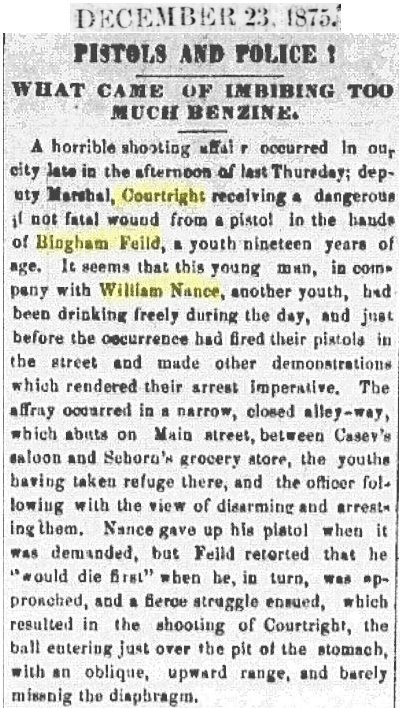

On the night of December 16, 1875, nine days before Christmas, William Nance, sixteen, and Richard Alexander (“Bingham”) Feild, nineteen, were carousing downtown, shooting their pistols. “Maddened and crazed by liquor,” the Fort Worth Democrat reported.

On the night of December 16, 1875, nine days before Christmas, William Nance, sixteen, and Richard Alexander (“Bingham”) Feild, nineteen, were carousing downtown, shooting their pistols. “Maddened and crazed by liquor,” the Fort Worth Democrat reported.

Richard Feild was the son of civic leader Julian Feild. William Nance surely was William F. Nance, son of Gideon Sr. William Nance was listed in the 1870 census (see above) as being eleven years old.

According to Jim Courtright biographer Robert DeArment in Jim Courtright of Fort Worth: His Life and Legend, on the night of December 16, 1875 newly appointed deputy city marshal Courtright had been on the job just two days. His first arrest did not go well. He heard gunshots being fired by William Nance and Richard Feild and cornered the two boys in an alley. He told them to surrender their guns. Nance complied. But Feild refused. When Courtright attempted to take the gun from Feild, it discharged. Courtright was shot in the stomach. For a while his life was despaired of. Had Courtright died, young Feild would have faced a murder charge. Young Nance might have faced a lesser charge.

Courtright recovered. No one went to jail. And three years later Ella Cooper, her mother M. M., her grandmother Levisa Bloodgood, and her son Willie—Fort Worth’s future first major leaguer and the “Texas Terror”—were living in the Nance house.